0% found this document useful (0 votes)

29 views12 pagesUnderstanding Handwriting Development

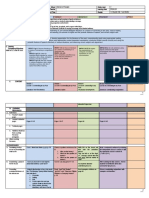

The document discusses handwriting as an important skill that involves both motor and cognitive processes. It develops from ages 3-4 and impacts academic success. Approximately 10-30% of children have difficulties with handwriting. The Simple View of Writing model shows how handwriting, spelling, and executive functions relate to writing. Handwriting involves integrating orthographic, phonological, and motoric codes and contributes directly to compositional fluency and quality.

Uploaded by

gauri horaCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online on Scribd

0% found this document useful (0 votes)

29 views12 pagesUnderstanding Handwriting Development

The document discusses handwriting as an important skill that involves both motor and cognitive processes. It develops from ages 3-4 and impacts academic success. Approximately 10-30% of children have difficulties with handwriting. The Simple View of Writing model shows how handwriting, spelling, and executive functions relate to writing. Handwriting involves integrating orthographic, phonological, and motoric codes and contributes directly to compositional fluency and quality.

Uploaded by

gauri horaCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online on Scribd