Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Cal A Bar

Uploaded by

Uwem ItangOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Cal A Bar

Uploaded by

Uwem ItangCopyright:

Available Formats

Calabar, city and seaport in southeastern Nigeria, capital of Cross River State, on an estuary of the Gulf of Guinea.

It is a major transportation center, with good road connections to the rest of southeastern Nigeria and neighboring Cameroon, an excellent natural harbor, and an airport. The city is the market center for the surrounding area in which cacao, palm oil, piassava, rubber, and timber are produced. Industries include sawmilling, boat building, cement and ceramics

production, and food processing. The city is the site of the University of Calabar (1975) and the Federal Polytechnic, Calabar (1973). Calabar dates from the 17th century, when it was a prominent slave-trading port. During the 19th century it became a center for trade in palm oil and palm kernels. From 1885 to 1906 Calabar was the center for British administration of southern Nigeria. The Efik are the citys

dominant ethnic group. Population (1995 estimate) 170,000.

Socrates in His Own Defense Thou doest wrong to think that a man of any use at all is to weigh the risk of life or death, and not to consider one thing only, whether when he acts he does the right thing or the wrong, performs the deeds of a good man or a bad If I should be found to be wiser than the multitude, it would be in this, that having no adequate knowledge of the Beyond, I do not presume that I have it. But one thing I do know, and that is that to do injustice or turn my back on the better is alike an evil and a disgrace. And never shall I fear a possible good, rather than avoid a certain evil If you say to me, 'Socrates, Anytus [one of Socratess prosecutors] fails to convince us, we let you go on condition that you no longer spend your life in this search, and that you give up philosophy, but if you are caught at it again you must die'my reply is 'Men of Athens, I honour and love you, but I shall obey God rather than you, and while I breathe, and have the strength, I shall never turn from philosophy, nor from warning and admonishing any of you I come across not to

disgrace your citizenship of a great city renowned for its wisdom and strength, by giving your thought to reaping the largest possible harvest of wealth and honour and glory, and giving neither thought nor care that you may reach the best in judgement, truth, and the soul' So God bids, and I consider that never has a greater good been done you, than through my ministry in the city. For it is my one business to go about to persuade young and old alike not to make their bodies and their riches their first and their engrossing care, but rather to give it to the perfecting of their soul. Virtue springs not from possessions, but from virtue springs possessions and all other human blessings, whether for the individual or for society. If that is to corrupt the youth, then it is mischievous. But that and nothing else is my offending, and he lies who says else. Further I would say, O Athenians, you can believe Anytus or not, you may acquit or not, but I shall not alter my conduct, no, not if I have to die a score of deaths. You can assure yourselves of this that, being what I say, if you put me to death, you will not be doing greater injury to me than to yourselves. To do me wrong is beyond the power of a Meletus [another of Socratess prosecutors] or an Anytus.

Heaven permits not the better man to be wronged by the worse. Death, exile, disgraceAnytus and the average man may count these great evils, not I. A far greater evil is to do as he is now doing, trying to do away with a fellow-being unjustly. O Athenians, I am far from pleading, as one might expect, for myself; it is for you I plead lest you should err as concerning the gift of God given unto you, by condemning me. If you put me to death you will not easily find another of my sort, who, to use a metaphor that may cause some laughter, am attached by God to the state, as a kind of gadfly to a big generous horse, rather slow because of its very bigness and in need of being waked up. As such and to that end God has attached me to the city, and all day long and everywhere I fasten on you, rousing and persuading and admonishing you Be not angry with me speaking the truth, for no man will escape alive who honourably and sincerely opposes you or any other mob, and puts his foot down before the many unjust and unrighteous things that would otherwise happen in the city. The man who really fights for justice and right, even if he expects but a short career, untouched, must occupy a private not a public station

Clearly, if I tried to persuade you and overcame you by entreaty, when you have taken the oath of judge, I should be teaching you not to believe that there are gods, and my very defence would be a conviction that I do not pay them regard. But that is far from being so. I believe in them as no one of my accusers believes. And to you I commit my cause and to God, to judge me as seemeth best for me and for you. [The jurors find Socrates guilty.] Men of Athens, many things keep me from being grieved that you have convicted me. What has happened was not unexpected by me. I am rather surprised at the number of votes on either side. I did not think the majority would be so little. As it is the transference of thirty votes would have acquitted me A fine life it would be for one at my age always being driven out from one city and changing to another. For I know that whithersoever I go the young men will listen to my words, just as here. If I drive them away, they themselves will have me cast out, and if I don't drive them away their fathers and relatives will cast me out for their sakes. [The jurors proceed to sentence Socrates to death.]

O men, hard it is not to avoid death, it is far harder to avoid wrongdoing. It runs faster than death. I being slow and stricken in years am caught by the slower, but my accusers, sharp and clever as they are, by the swifter wickedness. And now I go to pay the debt of death at your hands, but they to pay the debt of crime and unrighteousness at the hand of Truth. I for my part shall abide by the award; let them see to it also. Perhaps somehow these things were to be, and I think it is well Wherefore, O Judges, be of good cheer about death, and know of a certainty that no evil can happen to a good man, either in life or after death. He and his are not neglected by the gods, nor has my own approaching end happened by mere chance. But I see clearly that to die and be released was better for me; and therefore the oracle gave no sign. For which reason, also, I am not angry with my condemners, or with my accusers; they have done me no harm, although they did not mean to do me any good; and for this I may gently blame them. Still I have a favour to ask of them. When my sons are grown up, I would ask you, O my friends, to punish them, and I would have you trouble them, as I have troubled you, if they seem to care about riches, or anything, more than about virtue; or if they

pretend to be something when they are really nothing, then reprove them, as I have reproved you, for not caring about that for which they ought to care, and thinking that they are something when they are really nothing. And if you do this, I and my sons will have received justice at your hands. The hour of departure has arrived, and we go our waysI to die, and you to live. Which is better God only knows. Source: The Penguin Book of Historic Speeches. MacArthur, Brian, ed. Penguin Books, 1996.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Soprano Saxophone - Wikipedia PDFDocument17 pagesSoprano Saxophone - Wikipedia PDFUwem ItangNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Guarantor FormDocument1 pageGuarantor FormSegunOdewoleNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Postinor Cheap Pills PDFDocument5 pagesPostinor Cheap Pills PDFUwem ItangNo ratings yet

- Examinations Leading To The Award of Certificate of CompetencyDocument2 pagesExaminations Leading To The Award of Certificate of CompetencyUwem ItangNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Examinations Leading To The Award of Certificate of CompetencyDocument2 pagesExaminations Leading To The Award of Certificate of CompetencyUwem ItangNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- STCW Approved Training InstDocument2 pagesSTCW Approved Training InstUwem ItangNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Expecting Adam: by Martha BeckDocument6 pagesExpecting Adam: by Martha BeckPIPER BROWNNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- FFA Membership, Ethics, Degrees, and Awards: ObjectivesDocument9 pagesFFA Membership, Ethics, Degrees, and Awards: ObjectivesSophia BrannemanNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- TASK 2 - BSBCUS501 Develop A Customer Service PlanDocument6 pagesTASK 2 - BSBCUS501 Develop A Customer Service PlanVioleta Hoyos Lopez100% (2)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Stakeholder CommunicationDocument19 pagesStakeholder CommunicationMohola Tebello Griffith100% (1)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- PTA (TGT) Contract 13012015 RamanDocument15 pagesPTA (TGT) Contract 13012015 Ramanसबका बापNo ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

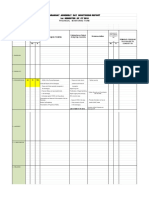

- Barangay Assembly Monitoring Report for Davao del SurDocument6 pagesBarangay Assembly Monitoring Report for Davao del SurDILG STA MARIANo ratings yet

- IdiosyncrasyDocument98 pagesIdiosyncrasyShazil AhmadNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Canadian Business LawDocument27 pagesCanadian Business LawSurya Cool100% (2)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Negosiasi BisnisDocument20 pagesNegosiasi BisnisFaisal FajriNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Rights Theory & Character EthicsDocument2 pagesRights Theory & Character Ethicsprashnita chandNo ratings yet

- Robert OwenDocument11 pagesRobert OwenNazzir Hussain Hj MydeenNo ratings yet

- Possession and its KindsDocument5 pagesPossession and its KindsKim RachelleNo ratings yet

- Statutory Construction ReviewerDocument8 pagesStatutory Construction ReviewerJane Irish GaliciaNo ratings yet

- Being Judgemental and Creative Writing ThemesDocument6 pagesBeing Judgemental and Creative Writing ThemesTava RajanNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Humanistic Theories of OrganizationsDocument16 pagesHumanistic Theories of OrganizationsYnaffit Alteza Untal100% (1)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Resume Profile: Queen Munyiva Musyoka Cell Phone:0722 879 480Document4 pagesResume Profile: Queen Munyiva Musyoka Cell Phone:0722 879 480Anonymous u06Ho6vvNo ratings yet

- Property disputes and family relationsDocument6 pagesProperty disputes and family relationsJongJongNo ratings yet

- Bernabe CastilloDocument3 pagesBernabe CastilloMitchi BarrancoNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- SEO-Optimized Title for Paramount Life Insurance Application FormDocument2 pagesSEO-Optimized Title for Paramount Life Insurance Application FormJhunalyn ManahanNo ratings yet

- 2017 GCDP Position Paper Opioid Crisis ENGDocument20 pages2017 GCDP Position Paper Opioid Crisis ENGBenjamin CMNo ratings yet

- Municipal Ordinance #7Document4 pagesMunicipal Ordinance #7eabandejas973100% (1)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- A Tale of Good Governance - The Story of Mayor Jesse RobredoDocument11 pagesA Tale of Good Governance - The Story of Mayor Jesse RobredoSabrine Travistin100% (1)

- Teresita Dio Versus STDocument2 pagesTeresita Dio Versus STmwaike100% (1)

- Basic Ethics Terminology FinalDocument25 pagesBasic Ethics Terminology FinalvivekanandgNo ratings yet

- Asset Protection PDFDocument37 pagesAsset Protection PDFKomishin100% (2)

- Job Interview RoleplayDocument4 pagesJob Interview RoleplayRandall Adolfo Orozco MorenoNo ratings yet

- 3 Ketu (South Node) Rahu (North Node) Life Learning in AstrologyDocument4 pages3 Ketu (South Node) Rahu (North Node) Life Learning in AstrologyRahulshah1984No ratings yet

- POLITICAL IDEOLOGIES Lesson 2Document1 pagePOLITICAL IDEOLOGIES Lesson 2CJ EtneicapNo ratings yet

- Veterans Day ProclamationDocument1 pageVeterans Day ProclamationRamblingChiefNo ratings yet

- Bus 5115 Unit 1 Written AssignmentDocument7 pagesBus 5115 Unit 1 Written Assignmentchristian allosNo ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)