Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Phone Use On Individual Social Capital

Phone Use On Individual Social Capital

Uploaded by

Fredy CanoOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Phone Use On Individual Social Capital

Phone Use On Individual Social Capital

Uploaded by

Fredy CanoCopyright:

Available Formats

Proceedings of the 44th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences - 2011

The Impact of Mobile Phone Use on Individual Social Capital

Song Yang University of Melbourne yangsong78@hotmail.com Sherah Kurnia University of Melbourne sherahk@unimelb.edu.au Stephen P. Smith Monash University and University of Melbourne Stephen.Smith@monash.edu resources that enable social interactions between people, and that people value access to these relational resources [7-12]. Studies indicate that efforts to build social capital have led to positive economic and sociological outcomes including improved quality of life [13], improved national economic performance [14] and faster diffusion of innovations [15]. To date, the definition of social capital adopted in any given study has depended on the focus of the investigation [16]. Because the focus of this study is on the use of the mobile phone as a social capital tool, the definition used here is derived from the research tradition that treats social capital as a function of interpersonal interactions and a resource that can be enhanced through investments in relationship-building technologies, particularly communication technologies [7]. Social capital, from this perspective, is the strength of an individuals network of social relationships and the qualities of those relationships. The stronger the network, the greater the ability of that person to associate with others for mutual benefit [7]. Social capital is a volatile resource, however. It requires continuing interaction and mutual trust amongst participants, and dissipates unless there is ongoing maintenance of existing relationships and initiation of new relationships [17]. The mobile phone is significant in this context. Because it is not tied to a particular place, it allows people to overcome (to some extent) the time and place constraints of older communication methods, such as landline telephony and face-to-face communication. The penetration rate of this technology has been phenomenal, to the extent that a number of regions (Europe and CIS) have passed the 100 per cent penetration mark and the worldwide penetration stood at 67 per cent by the end of 2009 [18]. Compared to other ICT, the mobile phone is the first technology that clearly defines itself as a possession for personal use, and accompanies each person all the time. Moreover, it synthesizes features of many other technologies, such as the Internet and digital organizer, and has thus become an all-purpose communication device. In reshaping human interactions, ICT have been promoted by some as a new type of glue that can hold social networks together more effectively while avoiding social exclusion based on geographical proximity [19]. However, research into this area is still

Abstract

Mobile phones have been diffusing worldwide at an astonishing rate. They provide individuals with unprecedented connectivity to information and interpersonal interaction, and thus are expected to enhance social capital. This paper sets out to present an investigation focusing on the impact of mobile phone use on individual social capital. Based on the case studies conducted in Australia and South Korea, we find that mobile communications, facilitated by mobility and portability of mobile computing, can have a positive impact on individual social capital and the degree of the impact largely depends on an individuals mobile phone use pattern. We then discuss the implications of the study and make suggestions for future research.

1. Introduction

Ownership and use of mobile phones has spread worldwide at an astounding rate. Apart from point-topoint voice communication, a variety of data communication services are available, including Short Message Service (SMS) and mobile Internet. The number of communication options available provides individuals with an unprecedented capability to interact with others and has contributed to the development of the mobile phone as a pervasive and significant social phenomenon [1]. Many people depend heavily on mobile communications technology to manage family, social and work commitments [2, 4], and social scientists have for some time been aware that mobile information and communication technologies (ICT) are transforming everyday social interactions [2] and even personal conceptions of time and space [3]. Some studies indicate that the mobile phone enables social interactions and communications in a far wider area than the traditional landline, and in so doing increases the opportunities for social interaction [4-6]. However, there is also evidence that a reliance on mobile technology for interpersonal communications can result in social isolation and an inability to access social resources [6]. A theoretical foundation of research into the social dynamics of communication networks is social capital theory, which posits that a social network is a nexus of

1530-1605/11 $26.00 2011 Crown Copyright

Proceedings of the 44th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences - 2011

in its early stages, and has not produced consistent results. Some researchers claim that electronic communication technologies are destroying the social capital base [6, 12, 20], whereas others argue that ICT actually facilitates and enhances social capital building [4, 5, 15]. This lack of consistency indicates a need for further research into the impact of ICT on social capital formation and suggests that the relationship is complex, producing both positive and negative effects. With the above issues in mind, this study examines how mobile phone use is associated with changes in individual social capital, focusing on the research question: How does mobile phone use affect social capital? For the purpose of this study, a multiple case study was conducted in Australia and South Korea to explore motivations, actions, and effects of mobile phone use on social capital. This study offers several contributions. It provides a synthesis of prior research in the area of ICT adoption and social capital to highlight the gaps in the current studies; offers a novel approach in assessing influences of mobile communications on social capital; and provides a typology of social capital level and that of mobile phone use to show how the two concepts inter-relate. The paper is organized as follows. The next section reviews current research into ICT and social capital. Section 3 explains the design of this study. Sections 4 and 5 describe the informants and our empirical findings, respectively. Finally, Section 6 discusses the implications of this study and concludes the paper.

such as those by Bourdieu [7] and Coleman [9], mainly regard social capital as resources generated by an individuals social network for his or her mutual benefits. Social capital defined from this perspective is called individual social capital [10]. Others, including Putnam [11, 12, 23] and Woolcock and Naryyan [24], consider social capital as both peoples social networks and their moral attitude or social norms contributing to the common good of a whole community or even a nation. Social capital defined from this perspective is referred to as collective social capital [10].

2.2. Research into social capital and ICT

IS researchers are increasingly becoming aware of the important role of social capital in technology development and knowledge-sharing processes [15, 25]. Based on our synthesis of the literature, three key issues have been identified as discussed below: 2.2.1. Imbalance in analysis levels. The majority of social capital related ICT studies measure social capital at the collective level. This is partly because social capital theory flourished only after the introduction of collective social capital by Putnam. The most noteworthy drivers for researchers and policymakers to pay attention to social capital are: (a) the potential benefits it may provide to communities, and (b) the changes of social capital in communities, especially the decline of social capital warned by Putnam. 2.2.2. Issues regarding generalization. Studies of the mediating role of ICT on social capital formation have tended to focus on a single technology, such as instant messaging or SMS. Despite the fragmented nature of this body of research, findings consistently indicate that ICT has many positive impacts on social capital building processes [2, 5, 6]. It is notable that most recent studies examine the role of the Internet or community networks in building social capital, while previous studies, apparently following Putnam, focus on technologies that are less socially orientated, such as TV or business information systems. These findings suggest that the effects of ICT on social capital may differ according to the type of technology investigated. 2.2.3. Lack of theoretical explanation about why and how social capital changes due to ICT. Much information systems research is devoted to what, as opposed to why or when relationships exist [26]. Likewise, existing theory does not provide an adequate explanation as to why ICT consumption leads to changes in social capital. For example, Putnams [12] explanation for why frequent TV watching results in

2. Background literature

2.1. The concept of social capital

Social capital is not a new concept in sociological research. Classical social theories, such as works of Durkheim and Marx, have long proposed that the involvement and participation in groups can have positive consequences for individuals and communities [10]. The first systematic analysis of social capital was made by Pierre Bourdieu [7] and a clear theoretical framework was developed by James Coleman [9, 21] who was also the first to conduct the empirical investigation on this concept [22]. It is Robert Putman who correlated levels of social capital with traditional public policy concerns and successfully exported the concept into mainstream discussion [11, 12]. Research into social capital is becoming more common across many social science disciplines, such as sociology, politics, public health and economics, among others. These studies of social capital can be roughly grouped into two categories: individual social capital and collective social capital. Some theories,

Proceedings of the 44th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences - 2011

declining social capital is that watching things (especially electronic screens) occupies more and more of our time, while doing things (especially with other people) occupies less and less (p. 9). However, this explanation cannot be generalized to explain and predict the relationships between mobile technologies and social capital. The majority of other studies of ICT use and social capital report only the association or relationship between those two variables, and make no effort to explain the association [41].

2.3. Mobile phone use and social capital

At the end of 2009, there were approximately 4.6 billion subscriptions to mobile phone services, and more than 600 million mobile broadband connections worldwide [27]. Clearly, mobile phone use has become integrated into everyday life for many people. However, no technological advance occurs without affecting society in some way. Srivastrva [6], for example, argues that our increasing dependence on personal mobile communication technologies is transforming fundamentally the nature of relationships, social interactions and even individual human identity. Because relationships are the foundation for social capital, mobile phone use is also transforming how we form and maintain social capital. Unfortunately, research to date provides little insight into the nature of this transformation. In this study we seek to address this gap by examining social capital formation from the individual perspective to assess the relationship between an individuals mobile phone use and his/her social capital. We are not, however concerned with how mobile phones affect collective social capital.

telecommunications sector. Compared to many countries in the Asia-Pacific region, such as Japan and South Korea, Australia is a large territory with a relatively small population density. The population is concentrated mainly in the coastal cities including five state capital cities. Consequently, there is an advanced, high quality mobile infrastructure serving the city business districts of state capitals and major towns, but poor coverage in rural and regional Australia [29]. The Korean mobile market is more mature than the Australian market in terms of mobile technology development. It has the highest mobile penetration rate in the Asia-Pacific region and the largest proportion of mobile Internet users in the world [30]. Internationally, the Korean broadcasting and communications industry is recognized for its competitive strength and the quality of its infrastructure [31]. As the first country in the world to offer CDMA service, Korea has consolidated its leading role in world mobile telecommunication market. It provides a very good lens for considering the future development of mobile technology, especially 3G, or even 4G mobile services. Moreover, finding similar results despite the large differences between Australia and Korea enhances claims regarding the generalizability of findings.

3.2. Research design and data collection

3.2.1. Research methodology. Because of the complicated nature of the social behavioral issues investigated here, we selected an interpretive and qualitative method that could provide rich and comprehensive data, specifically a multiple case study approach using the diary-interview method. The diaryinterview method involves participants recording activities in a diary over a specified period and explaining those activities in brief interviews [32]. This method is regarded as a good substitute technique for direct observation. In this study, each informant was initially interviewed about his/her mobile phone use in general, and then asked to record in detail all mobile phone use and related activities over a seven-day period, with a follow-up interview to clarify the entries in the diary in the week after the diary was completed. 3.2.2. Measurement of social capital. There are two schools of individual social capital measurement: (1) the social network tradition that assesses capital using an approach variously called the Name Generator, the Position Generator and the Resource Generator [33]; and (2) multi-dimensional measurements of variables such as trust, social norms, and civic participation, [6, 22, 25]. These two approaches do not conflict, but instead represent different perspectives. Because each

3. Research design

3.1. Site selection

Site selection is fundamental to the validity of qualitative research [28]. Two research sites, Australia and South Korea, were chosen for this study because both have a large urbanized population, and the major population centers are served by advanced, high quality mobile infrastructure [29, 30]. The high urban density is important because dense social networks have been shown to be a key determinant of the penetration rate for a new technology [2], and it was important for this study that all participants had equal access to high-quality technical infrastructure (to rule out technical reasons for observed differences). The Australian mobile industry is a fast-growing and increasingly significant part of the Australian

Proceedings of the 44th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences - 2011

is a potentially valuable source of insight, in this study we assess social capital from both perspectives. Based on understanding of social capital from social network theories, the Resource Generator, measuring individual social capital based on the resources embraced in ones social networks that may benefit parties within the networks, was used to measure social capital in the initial interviews. It asks about access to various social resources and the expected use of each resource. Two indicators, social capital accessibility and social capital mobilization, were assessed. According to the multi-dimensional measurement of social capital, the participants social network within their civic participation level (activities in formal and informal organizations), social norms (reciprocity and voluntary work) and perceived trust to others are complementary measures of social capital. Questions about each were asked in follow-up interviews. 3.2.3. Unit of analysis and targeted population. The unit of analysis in this study is the individual rather than any collective structure such as a community or nation. The target population is young people aged between 18 and 26. Young people are the most active mobile phone users and differ significantly from teenagers and the professionals in terms of social capital perceptions [34]. To access this population, full-time undergraduate students in a variety of universities were recruited. 3.2.5. Coding. Because of the fixed-structure of the questionnaire (initial interview), diary and follow-up interviews, the coding of the data is straightforward. A codebook was developed based on previous research into social capital and mobile phone use. The diaries were analyzed using SPSS15, and the interview transcripts were analyzed using NVivo8.

combines questionnaires, diaries and interviews also enhances the credibility of the study. Transferability is the degree to which findings can be generalized to other contexts or settings. In this project, the research context, the assumptions, the research process and the method used to code raw data for analysis were described in detail, so that other researchers who want to transfer the findings to a different context can make the judgment of how appropriate the transfer is. The inclusion of two countries with different conditions also helps enhance the transferability of the findings. Dependability corresponds to the conventional term "reliability," and confirmability parallels "objectivity" in qualitative research. Both require maintenance of a clear audit trail to document and link each stage of the research process [36]. In this project, the audit trail includes notes about research procedures, audio recordings, interview guides and transcripts, lists of interviewees and categories, and so on. Three experienced researchers audited the project. Causal attributions are possible though this methodology because the rich qualitative data collected using multiple methods (to triangulate observations) provides access to motives which allows researchers to reconstruct the causal chain leading up to that event. Acknowledging the limits of this approach, we make attributions of causality here based on common themes in the stated reasons for a recorded behavior.

4. The informants

In Australia, thirteen full-time undergraduate students (6 females and 7 males) from five universities in Melbourne participated in the project. In South Korea, sixteen students (10 females and 6 males) from four universities completed the study. All demographic information is summarized in Table 1.

3.3. Research validity

To maximize the validity of this qualitative research, we have taken steps to ensure high levels of credibility, transferability, dependability and confirmability [35]. In qualitative research, work is credible if it describes the phenomena of interest from the participant's perspective (on the assumption that only a participant can legitimately assess a report of his or her experience). To ensure credibility, the first author, a PhD student in Australia and a visiting student in South Korea, built trust with the informants gradually by spending time with them during the project period. Pilot tests were conducted in both countries to ensure that procedures were unlikely to bias data, and the triangular research design that

5. Findings

This project was designed to reveal and explain the relationship between mobile phone use and individual social capital, with the expectation of generating a classification schema to represent social capital levels, and another to classify individual mobile phone use patterns. Kluge [37] suggests a four-stage approach to construct typologies in qualitative research. This starts with the development of relevant dimensions (Stage 1). Cases are then analyzed for empirical regularities (Stage 2), followed by assessment of relationships between regularities (Stage 3), and construction of types (Stage 4). This four-stage mode enables typologies to be built systematically and transparently,

Proceedings of the 44th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences - 2011

and was adopted to classify the social capital levels (Section 5.1), phone use patterns (Section 5.2) and the relationships between both constructs (Section 5.3). Table 1. Demographic details of informants

Characteristics Age 18-20 21-23 24 + Gender Female Male Part-time No job? Yes Family No support? Yes Family Low income Low-med level Medium Med-high High Lives with No family? Yes Marital Single status Married Other/unknown Has No children? Yes Australia No. % 7 53.8 5 38.5 1 7.7 6 46.2 7 53.8 5 38.5 8 61.5 4 30.8 9 69.2 3 23.1 1 7.7 4 30.8 3 23.1 2 15.4 9 69.2 4 30.8 13 100 0 0 0 0 12 92.3 1 7.7 Korea No. % 2 12.5 10 62.5 4 25 10 62.5 6 37.5 12 75 4 25 3 18.8 13 81.2 3 18.7 3 18.7 5 31.2 3 18.8 2 12.5 9 56.3 7 43.7 15 93.7 1 6.25 0 0 16 100 0 0

social position in a given social network. Informants who scored high in Steps 1 and 2 are labelled Activists. These have the highest social capital, a large number of friends, and often play a leading role in social events. They are also able to utilize the social resources of their social contacts to achieve a goal (mobilize other peoples contacts and social resources). Informants who scored medium in Step 1 and high in Step 2, are labelled Leaguers. They have a high current social resources score, but the social network is not as strong as that of an Activist. A leaguer is usually an active member of a social network, but not a leader. Informants, who score low in Step 2, but high or medium in Step 1, are called Wanderers. They tend to have looser social contacts and are less goal-driven socially than activists and leaguers. The remaining informants are low on both dimensions and are labelled Fringe Dwellers. These tend to communicate infrequently and feel isolated. They are also the least confident in utilizing social resources owned by others.

5.1. Individual social capital

In this study, social capital is measured using three indicators: accessibility of social resources, ability to mobilize social resources, and involvement with collective assets. The values recorded for each informant are shown in Figure 1. Accessibility and mobilization use the Resource Generator approach to assess an individuals current stock of social resources, while collective assets, following the multidimensional measurements, indicates the status of ones social network and moral attitude, with reflects a persons potential to obtain social resources for mutual benefits. To discover meaningful clusters from the data, we grouped informants according to their social capital values. This grouping was performed in three steps using the analysis approach suggested by Kluge [37]. In Step 1, we ranked each countrys informants and categorized them into a low, medium, or high band based on the Resource Generator analysis. In Step 2, informants were re-ranked and grouped according to the results of the multi-dimensional measurements. By combining the results from both perspectives, four subgroups were identified, as indicated in Figure 1. Given the small sample size in this study, the social capital level identified in this study is not an absolute value, nor a latent trait, but a value symbolizing ones relative

Figure 1. Results of Social capital measurements

5.2. Informants mobile phone use

Mobile phone use data was assessed in two phases: (1) identifying overall use patterns, and (2) examining logs of daily mobile service use to differentiate each mobile use pattern further. In the first phase, three aspects of informants mobile phone use were examined: previous phone history, present usage, and attitude towards the importance of mobile phones in their social life, in line using the analysis techniques suggested by Kluge [37]. Four patterns, Passionate,

Proceedings of the 44th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences - 2011

Active, Neutral and Passive, were identified. Passionate informants are enthusiastic users of mobile phones for communicating and organizing social activities. They value their mobile phone as an important, even essential, tool for managing social interactions, and (according to the diary data) use it more frequently than any other group. Seven informants are in this category (AU: SP, AT, RB, AH, KC; KR: KMH, LSJ). KMH, for example, reported 681 mobile phone involved activities (average among Korea informants: 266), among which, 629 were for social activities, such as organizing a night out. Active users also regard mobile phones as an important tool in their social life, and make frequent use of the mobile communication services (mainly SMS and voice calls) and the built-in functionalities.

Object Friend Purpose

Eight informants are in this category (Australia: JH, EH, JP, OR; Korea: LHK, HHS, JKY, KYR). They use the mobile phone less than passionates, but similarly initiate most communications by sending text messages or making calls (percentage reported in diaries >60%). Eight informants are classified as Neutral (AU: MT and CW; KR: PSY, PSR, KSH, JJE, SWH, and HJH). They see the mobile phone as a useful, but not critical, tool for their communication needs. Their frequency of use is close to the median, and they have no preference for initiating or receiving mobile communications. HJH, for example, reported 296 activities (mean in Korea: 266), of which she initiated around 50 per cent. The remaining informants (AU: JS, BS; KR: SCH, CJB, SJW, IMS) are termed passive users. They see

BF/GF/Spouse

Family

Acquaintance

Other

Notes:

Mobile Phone Use Patterns1 Country All Passionate Active Neutral Passive Australia 154 (24.1%) 22 (29.0%) 8 (16.9%) 2 (8.3%) 5 (23.1%) 2 Coordinating people Korea 475 (15.8%) 44 (16.5%) 49 (13.1%) 30 (23.2%) 3 (5.7%) Communicating status Australia 101 (15.8%) 10 (13.3%) 6 (13.2%) 9 (50.0%) 3 (15.4%) information Korea 370 (12.3%) 8 (3.0%) 51 (13.7%) 22 (17.0%) 5 (8.6%) Australia 154 (24.1%) 15 (20.2%) 16 (34.9%) 4 (22.2%) 1 (2.6%) Virtual conversing Korea 1015 (33.8%) 102 (38.0%) 138 (37.3%) 37 (28.2%) 9 (17.6%) Seeking/offering help or Australia 41 (6.4%) 4 (5.1%) 4 (7.9%) 2 (8.3%) 0 (0.0%) emotional support Korea 175 (5.8%) 37 (13.9%) 9 (2.4%) 9 (7.1%) 2 (2.9%) Australia 23 (3.6%) 4 (4.8%) 0 (0.0%) 0 (0.0%) 3 (12.8%) Coordinating people Korea 94 (3.1%) 13 (4.7%) 13 (3.4%) 3 (2.3%) 0 (0.0%) Communicating status Australia 13 (2.0%) 1 (1.6%) 1 (1.6%) 0 (0.0%) 2 (10.3%) information Korea 55 (1.8%) 2 (0.6%) 11 (3.0%) 1 (0.9%) 0 (0.0%) Australia 58 (9.1%) 8 (10.6%) 4 (7.4%) 0 (0.0%) 2 (10.3%) Virtual conversing Korea 442 (14.7%) 32 (11.8%) 62 (16.7%) 7 (5.7%) 22 (41.9%) Seeking/offering help or Australia 8 (1.3%) 2 (1.9%) 0 (0.0%) 0 (0.0%) 1 (2.6%) emotional support Korea 35 (1.2%) 9 (3.2%) 1 (0.1%) 3 (2.1%) 0 (0.0%) Australia 7 (1.1%) 1 (0.8%) 0 (0.0%) 1 (2.8%) 1 (5.1%) Coordinating people Korea 40 (1.3%) 0 (0.0%) 1 (0.3%) 0 (0.1%) 1 (1.4%) Communicating status Australia 22 (3.4%) 3 (4.3%) 1 (2.6%) 1 (2.8%) 0 (0.0%) information Korea 83 (2.8%) 3 (0.9%) 7 (1.8%) 5 (3.7%) 0 (0.0%) Australia 28 (4.4%) 2 (2.7%) 4 (7.4%) 0 (0.0%) 2 (10.3%) Virtual conversing Korea 88 (2.9%) 8 (2.8%) 8 (2.2%) 2 (1.5%) 6 (11.0%) Seeking/offering help or Australia 14 (2.2%) 2 (3.2%) 1 (1.1%) 0 (0.0%) 0 (0.0%) emotional support Korea 38 (1.3%) 1 (0.2%) 4 (1.1%) 2 (1.4%) 1 (1.0%) Australia 11 (1.7%) 2 (2.1%) 0 (0.0%) 1 (5.6%) 1 (2.6%) Coordinating people Korea 6 (0.2%) 0 (0.0%) 2 (0.5%) 3 (2.3%) 3 (5.7%) Communicating status Australia 6 (0.9%) 0 (0.0%) 1 (2.6%) 0 (0.0%) 1 (2.6%) information Korea 0 (0.0%) 0 (0.0%) 3 (0.9%) 2 (1.2%) 0 (0.0%) Australia 5 (0.8%) 0 (0.0%) 1 (2.6%) 0 (0.0%) 0 (0.0%) Virtual conversing Korea 22 (0.7%) 0 (0.0%) 2 (0.6%) 3 (2.4%) 0 (0.0%) Seeking/offering help or Australia 3 (0.5%) 1 (0.3%) 1 (1.1%) 0 (0.0%) 0 (0.0%) emotional support Korea 68 (2.3%) 12 (4.5%) 10 (2.6%) 1 (0.8%) 2 (3.3%) Australia 1 (0.2%) 1 (0.3%) 0 (0.0%) 0 (0.0%) 0 (0.0%) Coordinating people Korea 3 (0.1%) 0 (0.0%) 1 (0.2%) 0 (0.0%) 0 (0.0%) Communicating status Australia 1 (0.2%) 0 (0.0%) 0 (0.0%) 0 (0.0%) 1 (2.6%) information Korea 1 (0.0%) 0 (0.0%) 0 (0.0%) 0 (0.0%) 0 (0.0%) Australia 0 (0.0%) 0 (0.0%) 0 (0.0%) 0 (0.0%) 0 (0.0%) Virtual conversing Korea 3 (0.1%) 0 (0.0%) 1 (0.1%) 0 (0.0%) 0 (0.0%) Seeking/offering help or Australia 0 (0.0%) 0 (0.0%) 0 (0.0%) 0 (0.0%) 0 (0.0%) emotional support Korea 0 (0.0%) 0 (0.0%) 0 (0.0%) 0 (0.0%) 0 (0.0%) 1. Columns 4-7 show the frequency of each activity reported by each type of informant. 2. Each informant in Australia who was passionate about mobile phones used his/her phone 22 times (29% of total use) to coordinate friends, whereas those in Korea used the phone 44 times (16.5% of total use) for this purpose.

Table 2. Mobile Communications and Mobile Use Patterns

Proceedings of the 44th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences - 2011

the mobile phone as simply an instant communication tool. They use the phone regularly, but tend to receive rather than initiate, communications. JS, for example, recorded 22 mobile activities in a week, but initiated only six. In the second phase, activities reported in diaries were examined in detail to identify patterns of daily mobile phone use. Each entry was analysed from temporal, spatial and contextual perspectives. Despite the development of new mobile services, informants primarily use only basic communication services (SMS and audio calls). All informants were comfortable using mobile phones when most people are awake (between 8:00 and 22:00). However, heavy mobile phone usage was associated with using the phone beyond 22:00 hours (e.g. Informant AT Entry 3 Day 4 reported a conversation at 2:57 in the morning). More frequent mobile users (passionate and active) repeat some activities regularly, such as organizing a lunch with friends every weekday via SMS. They may have mobile communications with a large number of people and feel comfortable asking for help or support from them. By contrast, passive users are likely to contact people close to them and hardly have routines in their daily communications. They may also have trouble in asking help from others. The majority of these actions involve physical movement. In Australia, about half of the reported activities happened at the informants home, while 51.4% of the mobile activities reported by Korean informants took place at university. There is no strong evidence that the locations of activities involving mobile phone use differ because of individuals mobile use patterns. Informants mobile phone use is summarised in Table 2. This data indicates that most of the reported mobile communications occurred between intimate friends (Aust: 10.9%; Korea: 9.8%), other close friends (Aust: 52.6%; Korea: 63.0%), and family members (Aust: 7.8%; Korea: 6.3%), while communication with acquaintances (Aust: 5.0%; Korea: 9.8%) was infrequent. Although the specific activities differ considerably, each communication can be described using one of three categories: coordinating people (organize a social event such as lunch or a night out) communicating status information (current location) and virtual conversing (exchanging SMSs or making audio calls, instead of face-to-face communications).

Table 3. Social Capital and Phone Use Patterns

Social Capital Activist Passionate Active Neutral Passive Leaguer Wanderer Fringe Dweller

------------------MT, KSH JS, IMS SP, AT, KC KMH RB, AH, LSJ JP, HHS*, JH, LHK, EH, OR JKY, KYR CW, PSY, ------------ HJH, JJE SWH, PSR SCH, CJB, ------------ BS SJW

* Korean informants are shown in italics

HHS, use mobile phones heavily. By contrast, more socially isolated individuals, such as MT and IMS, are less engaged in mobile phone use. The remainder, who sit in the middle ground (leaguers and wanderers), have fewer collective assets than activists, but use the phone often to maintain and develop those assets. Note that no Passionate or Active user is a Fringe Dweller, and no Neutral or Passive user is an activist, suggesting that mobile phone use and social capital levels are related. Next, we explain in detail how mobile communication affects individual social capital. 5.3.1. The impact of mobile communication on collective assets. As stated in Section 3, collective assets were assessed using indicators of social network, reciprocity, volunteer work, and interpersonal trust. Our results indicate that mobile phones are a useful instrument to enhance a social network. Social capital theory proposes that tools that enhance a social network affect norms of reciprocity or trust directly [25]. However, no strong evidence was found here to suggest that mobile communications have any direct impact on either norms of reciprocity or trust. The impact of mobile phone use on an individuals social network is evident from efforts to preserve ones social network (maintaining existing relationships with friends and family members) and also efforts to expand the network (developing and extending relationships with acquaintances). For all informants, mobile communication is regarded as an easy and effective way to keep in touch with social contacts, and therefore help sustain social ties. Exchanging text messages or calling from time to time is the preferred way to maintain ties with a person who is not a close friend or family member. AT, for example, sends text messages occasionally to high school friends. She explains:

It is very nice to receive a message I think it is also very useful in keeping friendships, especially longdistance friendships Just let them know Oh, this person still thinks about me.

5.3. How mobile communications affect individual social capital

Combining the social capital and mobile phone use classifications in Section 5.1 and 5.2 produces a matrix that describes all informants (Table 3). This table shows that socially active individuals, such as SP and

In general, the less active an informant is with

Proceedings of the 44th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences - 2011

mobile communication, the larger the percentage of his/her mobile activities associated with strong ties with them (close friends and/or family members). The more active an informant is with mobile phone use, the larger the proportion of mobile actions for communicating with friends and/or acquaintances. Regarding the expansion of social networks, most informants believe that mobile phones are less useful than face-to-face or online communications. CW, for example, explains that mobile communications, (especially social) cannot start themselves nor begin a friendship from nowhere. People have to meet each other either physically in person or at some virtual space, such as online communities, to exchange mobile phone numbers and then contact each other. Both Australian and Korean informants agree that having mobile communications with others require a certain degree of trust to those people. However, mobile phone use itself contributes little to the informants trust on others directly. Moreover, no strong evidence is found to link mobile phone use and individuals norms of reciprocity in the study. 5.3.2. The impact of mobile communication on access to social resources. Two indicators, (a) the number of all contacts in the phonebook and (b) the number of the frequent contacts in the phonebook, are measured relating to the informants social network accessible over mobile phones. The former is a suggestive indicator about an informants social network including their potential social connections, as most of the informants intend to abandon paper phonebooks and keep all their contacts in the electronic phonebook in their mobile phones. The later, on the other hand, implies an informants close social relationships. Our data suggest that both indicators tend to decrease with the decline of enthusiasm about mobile phones (from the Passionate to the Passive). Specifically, mobile communications are found to affect ones access to social resources via three approaches: organizing face-to-face communications, encouraging distribution and obtainment of information, and facilitating virtual communications. Organizing face-to-face communications: All informants agree that face-to-face communications are the most effective way to establish and enhance social relationships and essential to develop trust. Mobile phones, as a tool for quick contacts, facilitate the coordination of such face-to-face interactions. 30.7% of mobile communications in Australia and 20.1% in Korea in this study were used to coordinate face-toface meetings. The more active a mobile phone user is, the more often he/she uses mobile phones for this purpose. In many cases, social meetings are arranged on a spur-of-the-moment impulse. KMH, for example,

said that she sometimes decides when she wakes up in the morning that she wants to do something with her friends on that day. Because of the immediacy of a mobile phone, she gives her friends a quick call or sends a few SMSs to arrange a casual get-together, including what to do, and when and where to meet. Enabling access to information about resource availability: Information about which resources are available and where they are located is critical in obtaining the resources or skills that one may need. Mobile communication provides informants with a channel that supports fast and easy access to such information within and among social networks. Mobile communications, in fact, make the social resources owned by one person within a network accessible to other parties within that network. OR explains:

If I call 10 people, it may end up with 25 people because they bring their cousins; they bring their friends. They may keep calling on their friends, you know, I may know their friends as well, so they are my friends now.

Comparing the informants of different mobile use patterns, the more enthusiastic one is about mobile communications, the more often he/she distributes information that may be interested by his/her friends, and the more likely he/she receives informant from others. RB, a passionate mobile user, for example, forwarded the detail of a public seminar held in another university via SMS to 12 of his friends (Entry 11, Day 4). In the follow-up interview, he explained that that was what he and a few friends often do to each other. We often forward information to each other. So, yeah, we are well informed, he stated. However, in the diaries of Passive users, such as JS and IMS, most mobile communications happened between close ties. No activities similar to the example given by RB were reported. Facilitating virtual communications: When informants cannot meet easily in person (e.g. high school friends who are now in another city, or are not able to see immediately because of the circumstance (e.g. late as night), mobile phones work as an instrument facilitating virtual communications, which transfer the long geographical distance into proximate virtual space. Nearly 40% of mobile communications in Australia and more than half in Korea are used for this purpose, usually between friends. The Passionate and the Active users usually spend much more time on virtual communication with others than the Neutral and the Passive users do. AH comments,

I think it (a text message to an old friend) is, even not that personal... it's nice to get a message from someone

Proceedings of the 44th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences - 2011

you havent heard of for a while. You sort of think oh, they must be thinking about me. Yeah, it just a nice way to keep the friendship, and an easy way.

likely to be able to ask them for help.

6. Discussion and conclusion

Mobile technologies are increasingly becoming a pervasive and ubiquitous part of life worldwide. Studies that extend our knowledge about the social consequences of mobile phones are therefore necessary. In this paper, we reported the results of a study using the diary-interview method on the role of mobile phones in establishing and maintaining social networks. By analyzing the data generated by the social capital measurements, four types of informants Activist, Leaguer, Wanderer and Fringe Dweller - each with different social capital level, emerge. Based on informants previous and current mobile phone use, four patterns of mobile phone use, Passionate, Active, Neutral, and Passive, are identified. By linking these two characteristics of the informants, it is found that the key features of mobile communications, enabled by the mobility and portability of mobile computing, indicate the potential for mobile communications to affect social capital (and social relationships more generally). Further analysis confirms that mobile phone use can have positive impacts on all three dimensions of social capital (i.e., collective assets, accessing and mobilizing social resources). The significance of this impact largely depends on an individuals mobile phone use pattern. In general, the more enthusiastic and active an individual is about mobile communications, the more positive the impacts generated through mobile phone use. Although the frequency of mobile phone use and impetus to adopt advanced mobile technologies in Korea is significantly higher than that in Australia, the impact of mobile phone on individual social capital in these two countries is largely consistent. Overall, it is clear that the mobile phone can be a useful tool for increasing an individuals stock of social capital. However, we find here that it is not a determinant of ones social relations or of ones social capital. Rather, an individuals mobile phone use reflects and is constantly shaped by his or her social capital. People with different social capital levels may have different perceptions and demands regarding mobile communications. Future studies are required to complement the findings of our study to further explore the complex interaction between mobile phones and social capital. Our classification of individual social capital and the typology of mobile phone use developed in this project can be particularly useful in guiding future research in this area.

5.3.3. The impact of mobile communication on mobilizing social resources. This was examined throughout the diaries and the follow-up interviews by addressing three issues: (1) whether mobile phones have been used for acquiring contacts resources or not, (2) If they have, what are the informants perceptions regarding using mobile phones to obtain those resources, and (3) what is the role of mobile phones in preparing informants for future mutual benefits via mobile contacts. The first two questions provide information about the direct impact of mobile phone on the use of contacts and their resources and the third provides information about the continuing impact of mobile phone use in making use of contacts resources. Lin [38] points out that one needs to manage access to the resources of others as well as maintain ones own resources. However, the mobile phone use data collected in the project only provides evidence that supports the former. The direct and the indirect use of contacts and contacts resources are discussed next. Direct use of contacts and contacts resources: This indicator is measured by the frequency of mobile communications used to mobilize embedded resources in an individual's social network. In total, 10.6% mobile communications reported in both countries were used for this purpose. The more active an informant in mobile communications, the more often he/she will use a mobile phone to seek help or support directly. Despite their differences, all informants agree that the convenience of mobile phones is helpful in contacting people and obtaining access to resources. Indirect impact on use of contacts and contact: This indicator refers to indirect effects on the mobilization of the embedded resources in an individuals social network. It describes the way people prepare others for a request for help or to share resources. It overlaps the effects of mobile phones on maintaining a social network and keeping contacts via physical and virtual channels. All informants agree that it feels strange to request assistance from somebody whom the requestor is not close to or has not contacted for a long time. In order to maintain connections (strong or weak) with others, mobile phones play a key role. Diaries show that informants send some messages for fun or to keep in touch. These messages contain little content, but the mere act of sending such a message shows that the sender wants to maintain ties, and is regarded as a form of insurance in the event that help is ever needed. As JH said:

...if you stay in good contact with them and build a good relationship, then you're trusted more and you are more

Proceedings of the 44th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences - 2011

7. References

[1] L. Kleinrock, "Nomadicity: Anytime, anywhere in a disconnected world," Mobile Networks and Applications, 1996. [2] H. Rheingold, Smart Mobs: the Next Social Revolution. Cambridge, MA: Persons Publishing, 2002. [3] A. M. Townsend, "Life in the Real-Time City: Mobile Telephones and Urban Metabolism," Journal of Urban Technology, vol. 7, pp. 85-104, 2000. [4] J. E. Katz, Magic in the air: Mobile communication and the transformation of social life. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 2006. [5] K. Hampton and B. Wellman, "Neighboring in Netville: How the Internet supports community and social capital in a wired suburb," City and Community, vol. 2, pp. 227-311, 2003. [6] L. Srivastrva, "Mobile phones and the evolution of social behaviour," Behaviour and Information Technology, vol. 24, pp. 111-129, 2005. [7] P. Bourdieu, "The Forms of Capital," in Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, J. G. Richardson, Ed., ed New York: Greenwald Press, 1986, pp. 241-255. [8] R. S. Burt, "Structural Holes versus Network Closure as Social Capital," in Social Capital: Theory and Research, N. Lin, et al., Eds., ed New York: Aldine de Gruyter, 2001. [9] J. S. Coleman, Foundations of Social Theory. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press, 1990. [10] A. Portes, "Social Capital: Its origins and Applications in Modern Sociology," Annual Reviews, vol. 24, pp. 1-24, 1998. [11] R. D. Putnam, "Turning in, Tuning Out: The Strange Disappearance of Social Capital in America," Political Science and Politics, vol. 28, pp. 664-683, 1995. [12] R. D. Putnam, Bowling alone: the collapse and revival of American community. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2000. [13] B. Kennelly, et al., "Social capital, life expectancy and mortality: a cross-national examination," Social Science & Medicine, vol. 56, pp. 2367-2377, 2003/6 2003. [14] C. Grootaert, et al., "Measuring Social Capital: an Integrated Questionnaire," The World Bank, New York2004. [15] J. E. Fountain, "Social capital: A Key Enabler of Innovation in Science and Technology," in Investing in Innovation: Toward A consensus strategy for Federal Technology Policy, L.M.Branscomb and J.Keller, Eds., ed Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1997. [16] L. J. Robinson, et al., "Is social capital really capital?," Review of Social Economy, vol. 60, pp. 1-24, 2002. [17] M. Kakihara and C. Sorensen, "Mobility: An Extended Perspective," in 55th Hawaii International Conference on Systems Sciences, 2002. [18] ITU. (2010, 3rd, June). World Telecommunication/ICT Development Report 2010 Monitoring the WSIS Targets. Available: http://www.itu.int/dms_pub/itu-d/opb/ind/D-IND-WTDR2010-PDF-E.pdf [19] J. Urry, "Mobility and Proximity," Sociology, vol. 36, pp. 255-274, 2002.

[20] S. Woolgar, "The virtual society reconsidered," Annales Des Telecommunications-Annals of Telecommunications, vol. 57, pp. 159-179, Mar-Apr 2002. [21] J. S. Coleman, "Social Capital in the Creation of Human Capital," The American Journal of Sociology, vol. 94, pp. S95-S120, 1988. [22] F. Adam and B. Roncevic, "Social Capital: Recent Debates and Research Trends," Social Science Information, vol. 42, pp. 155-183, 2003. [23] R. D. Putnam, "Bowling Alone: America's Declining Social Capital," Journal of Democracy, vol. 6, pp. 65-78, 1995. [24] M. Woolcock and D. Narayan, "Social capital: Implications for development theory, research, and policy," The World Bank Research Observer, vol. 15, pp. 225-249, 2000. [25] A. Syrjanen and K. Kuutti, "Trust, acceptance and alignment: the role of IT in redirecting a community," in IT and Social Capital, M. Huysman and V. Wulf, Eds., ed Cambridge: MA: MIT Press, 2004. [26] B. Lee, et al., "Discovery and Representation of Causal Relationships in MIS research: A Methodological Framework," MIS Quarterly, vol. 21, pp. 109-136, 1997. [27] ITU, "ICT Statistics Database," 2010. [28] K. M. Eisenhardt, "Building Theories From Case Study Research," Academy of Management. The Academy of Management Review, vol. 14, pp. 532-550, 1989. [29] ACMA, "Telecommunications Performance Report 2004 - 2005," Australian Communications and Media Authority, Melbourne2005. [30] A. Henten, et al., "Mobile communications: Europe, Japan and South Korea in a comparative perspective," info, vol. 6, pp. 197 - 207, 2004. [31] ITU. (2010, Accessed on Jan 5, 2010). Digital Opportunity Index and WSIS. Available: http://www.itu.int/ITU-D/ict/doi/index.html [32] D. H. Zimmerman and D. L. Wieder, "DiaryInterview Method," Urban Life, vol. 5, pp. 479-498, 1977. [33] M. P. J. Van der Gaag and T. A. B. Snijders, "The Resource Generator: measurement of individual social capital with concrete items," Social Networks, vol. 27, pp. 1-29, 2005. [34] E. Cox, "Australia: Making the Lucky Country," in Democracies in Flux: the Evolution of Social Capital in Contemporary Society, R. D. Putnam, Ed., ed: Oxford University Press, 2002, pp. 333-358. [35] Y. Lincoln and E. Guba, Naturalistic inquiry. New York: Sage, 1985. [36] E. G. Guba and Y. S. Lincoln, "Competing Paradigms in Qualitative Research," in Handbook of Qualitative Research, N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln, Eds., ed CA: Sage, 1994, pp. 105-117. [37] S. Kluge, "Empirically Grounded Construction of Types and Typologies in Qualitative Social Research," Forum: Qualitative Social Research, vol. 1, p. 14, 2000. [38] N. Lin, "Building a Theory of Social Capital," Connections, vol. 22, pp. 28-51, 1999.

10

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5814)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Inclusive Education in The Philippines: Study Guide For Module No. 1 (Las 2)Document9 pagesInclusive Education in The Philippines: Study Guide For Module No. 1 (Las 2)Maia GabrielaNo ratings yet

- TOEFL Diagnostic TestDocument47 pagesTOEFL Diagnostic TestLilian G. Romero L.No ratings yet

- Exegesis:: Luke 19-21. in The TempleDocument14 pagesExegesis:: Luke 19-21. in The TempleVincent De VeraNo ratings yet

- ROC Graphs: Notes and Practical Considerations For Data Mining ResearchersDocument28 pagesROC Graphs: Notes and Practical Considerations For Data Mining ResearchersJan ShumwayNo ratings yet

- Membangun Teori Dan Konsep Asuhan Kebidanan Kehamilan, Persalinan, Nifas, BBL, KB Dan KesproDocument28 pagesMembangun Teori Dan Konsep Asuhan Kebidanan Kehamilan, Persalinan, Nifas, BBL, KB Dan KesproNikytaNo ratings yet

- 2021-09-Network Design and Troubleshooting Assign-PART1Document10 pages2021-09-Network Design and Troubleshooting Assign-PART1Firdous JamalNo ratings yet

- Read Aloud HoorayDocument4 pagesRead Aloud Hoorayapi-298364857No ratings yet

- Self-Disclosure in CBTDocument14 pagesSelf-Disclosure in CBTSimona VladNo ratings yet

- Physical Development 1Document18 pagesPhysical Development 1September KasihNo ratings yet

- Sheikh Nadeem AhmedDocument19 pagesSheikh Nadeem Ahmednira_110No ratings yet

- Lesson Plan (1) FrogDocument4 pagesLesson Plan (1) FrogSabha HamadNo ratings yet

- TT4 Tests Unit 9BDocument2 pagesTT4 Tests Unit 9BSonia AdevaNo ratings yet

- Blue Rabbit - Dracula The VampireDocument9 pagesBlue Rabbit - Dracula The VampireAracelly MeraNo ratings yet

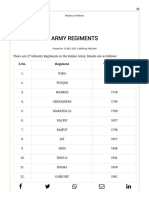

- Army Regiments: S.No. Regiment Year of RaisingDocument3 pagesArmy Regiments: S.No. Regiment Year of RaisingAsc47No ratings yet

- Jane Eyre Background - Power PointDocument11 pagesJane Eyre Background - Power PointOmar Shaikh100% (2)

- How To Disappear Completely and Never Be Found: Vanishing ActsDocument1 pageHow To Disappear Completely and Never Be Found: Vanishing ActsGalmanussssNo ratings yet

- The Religion of The Ancient Celts - 9781605061979Document345 pagesThe Religion of The Ancient Celts - 9781605061979null10100% (2)

- Transliteration-Telugu: Mokshamu Galada-SaramatiDocument8 pagesTransliteration-Telugu: Mokshamu Galada-Saramativishwa007No ratings yet

- Civil Law Ii: 2015 Compiled Case DigestsDocument80 pagesCivil Law Ii: 2015 Compiled Case DigestsTom SumawayNo ratings yet

- Course Schedule CAES9820 Sem 2 MonThuDocument4 pagesCourse Schedule CAES9820 Sem 2 MonThuyip90No ratings yet

- John McDowell, Wittgenstein On Following A Rule', Synthese 58, 325-63, 1984.Document40 pagesJohn McDowell, Wittgenstein On Following A Rule', Synthese 58, 325-63, 1984.happisseiNo ratings yet

- The King of The ForestDocument2 pagesThe King of The ForestSeanmyca IbitNo ratings yet

- 107年國營事業 (台電、中油…) - 共同科目 (國文、英文) PDFDocument4 pages107年國營事業 (台電、中油…) - 共同科目 (國文、英文) PDF林倉舒No ratings yet

- Atg Crossword Possadjpron SubjobjDocument3 pagesAtg Crossword Possadjpron SubjobjwhereswhalleyNo ratings yet

- Stanislavakian Acting As PhenomenologyDocument21 pagesStanislavakian Acting As Phenomenologybenshenhar768250% (2)

- Delta Dentists Near Nyc ApartmentDocument50 pagesDelta Dentists Near Nyc ApartmentSteve YarnallNo ratings yet

- Task 1Document10 pagesTask 1nino tchitchinadzeNo ratings yet

- Book M1Document42 pagesBook M1ychoquehuanca77No ratings yet

- Identifying Main Idea - 82684Document2 pagesIdentifying Main Idea - 82684Aira Frances BagacinaNo ratings yet