Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Dec 11 3-4

Uploaded by

dov_zigler2891Original Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Dec 11 3-4

Uploaded by

dov_zigler2891Copyright:

Available Formats

The European Flu of 2011

financial and political crisis is underway in Europe. Just listen to comments made by Europes leaders over the past two weeks. According to UK PM David Cameron, the European Union is an organization in peril representing a continent in trouble. Per Nicholas Sarkozy, the euro will sooner rather than later be too strong for some and too weak for others, and the euro zone will explode. German PM Angela Merkel perhaps overdid it when she said that Europe is in one of its toughest, perhaps its toughest hour since World War Two, but one gets the idea. As this article is being written, Mr. Sarkozy and Mrs. Merkel have announced their plans to reopen the fundamental European Union treaties. There is no question that Europe is sick. Since European markets began their convulsion in mid-July, the German DAX has posted a -18% return, the French CAC 40 a -17% return, the Spanish IBEX -18% and the Italian MIB -22%. As recently as November 25th, the declines were in the 20-30% band across the board. The Bloomberg European Financial Index has returned -35%. Major European banks including Barclays, Deutsche Bank, Banco Santander and Credit Suisse have seen their share prices decline by as much as 50% (or more in the cases of BNP Paribas, Societe Generale, and other major French lenders). The sovereign debts of nations such as Italy and Spain have been successively downgraded by ratings agencies and more importantly repriced by markets. When Italian yields shot up from 3.3% to 7.3% between early July and late November, it translated into mark-to-market declines of 30% or more for holders of Italian 10-year bonds. In this environment, it is almost astounding that the euro has only declined by 10% at its worst. To read the press, you would think that the causes of the turmoil are related exclusively to government policy. The conservative view, perhaps most forcefully expressed

GLOBAL PROSPECTS GLOBAL PROSPECTS

in the German magazine Der Spiegels series on the Euro-crisis, titled Die Geldbombe, is that the profligacy of the European welfare state is responsible for the crisis, and that the debt-to-GDP ratios of the weaker European states are ultimately caused by the spending policies of European governments. The more liberally-minded view, reliably and articulately presented in Financial Times economics editor Martin Wolf s twice-weekly column, is that a failure of growth-oriented government policy has prevented the GDP part of the debt-toGDP ratio from growing as rapidly or forcefully as it needs to in order to make Europes national debts palatable or even sustainable. While both views are simply true, neither fully explain the crisis as it has unfolded. The main issue is that on top of having to sustain costly welfare states, European nations need to bail out a financial system still laden with bad debts. Europe is in the midst of a banking crisis surrounding the challenges and costs of dealing with decades of bad debts, both private and public, accrued by Europes banking system. This European crisis is ultimately an extension of the global debt crisis which gripped the United States in 2007-08 and which was never addressed fully or openly on the continent. As in the United States, the resolution of the crisis will require a mix of fiscal intervention on the part of governments and monetary intervention on the part of Europes central bank, the ECB. However Europe is in a more vulnerable position than the United States circa 2008. The oversized debts of Europes sovereigns and the slow growth of Europes economies limit the flexibility of Europes fiscal policy. Moreover, the ECBs tight mandate to enforce price stability and not to serve as a lender of last resort limits the extent to which monetary policy can be applied. The end result is a highly volatile situation and profound fears that Europes financial flu of 2011 will transform into a contagion in 2012. Two strains of the virus Just as a doctor treating a patient surveys case history before prescribing a treatment, its imperative to understand the different species of European financial crisis prior to moving forward with a diagnosis of todays problems. Greece and Ireland, the early casualties of the European financial crisis, provide case studies of the varieties of European financial crisis. The Greek financial crisis is definitely the easier of the two to understand: Greeces government revenues are not sufficient to fund Greeces expenses, nor is it plausible that they can be brought to match the extent of Greeces needs in the near future. Between 2008 and 2010, Greeces government ran a cumulative deficit in excess of 83b EUR. Thats equal to 35% of Greeces nominal GDP and roughly double the average tax revenue of Greece, which has run at approximately 40b EUR per year for the past three years. Greeces Governments overspending over the past three years has been equal to half of its income in any given year. Unsurprisingly, global bond buyers have lost interest in capitalizing Greeces budgetary needs. Ireland presents a tougher puzzle. Ireland was one of the most stable and bestmanaged economies prior to the crisis and among its worst casualties. To give an idea of the extent of Irelands change, in 2007 Ireland ran a budget surplus. Its debtto-GDP ratio, which shrank throughout the decade, was 25%. Q4 2007 YoY real GDP growth was 6.2%. Today Irelands debt-toGDP level sits at 95%. What happened? Unlike Greece, Irelands financial crisis was not driven by basic structural deficits but rather by the one-off costs of bailing out the Irish banking system combined with the drop-off in corporate tax revenue. National tax receipts were 59.6b EUR in 2007 and 34.4b EUR in 2010. Meanwhile, the total costs of the Irish bank bailout, which are currently held off balance sheet, exceed

continued on page 4...

Page 3

Review & Outlook December 7,2011 Volume 35, Number 12

The European Flu of 2011

70b EUR, i.e. are greater than double Irelands annual tax revenue. How did Ireland get here? The anatomy of the bailout of Bank of Ireland (BKIR), one of Irelands largest lenders and probably its strongest, is instructive. BKIR has Challenged Loans (impaired, past due but not impaired, and lower quality loans) of 24.5b EUR against an impairment provision of 5b EUR. The market cap of BKIR is 2.7b GBP, implying that markets believe that between recoveries on distressed assets and loan-loss provisions, there is substantial equity left over on BKIRs balance sheet. Still, BKIR is a risky proposition, and as it funds 46% of its asset book via wholesale loans, i.e. via short term public borrowing, public markets will only remain open to BKIR if its assets are guaranteed. Thats where the government has had to step in. New equity has been infused by the government into BKIR through a variety of programs, and moreover, the government of Ireland has had to announce its willingness to backstop further losses that would accrue to the bondholders. In equity terms, the government has had to pay in more than 4b EUR since the crisis started while remaining on the hook for potentially larger equity infusions should the attrition of BKIRs loan book continue. Debt guarantees have sucked up additional capital. Repeat this process for the three other lower quality members of Irelands big four banks and the expense rises to 45b euros one quarter of Irelands GDP. Were all Irish now The challenge in Europe is not dissimilar from the one confronted by Ireland: bailing out banks in a context of weak tax returns and slow growth. The fiscal deficits themselves are not the challenge. With the exceptions of Greece and Portugal, the accumulated debts of European nations are not all that different today than they were at the start of the decade. For instance, Italys debt-to-GDP ratio was 106% in 2003

GLOBAL PROSPECTS

vs. 120% at the end of 2010. Frances 2003 vs. 2010 numbers are 69% vs 82%. Germanys are 64% vs. 83%. The Netherlands are 54% vs. 62%. Spains are 62% vs 62%, i.e. unchanged. The issue is not the debts themselves but rather what those debts would look like if massive bank recapitalization and loan guarantees were piled on top of them. Italys two largest lenders, Unicredit and Intesa Sanpaolo, have cumulative balance sheets of 1.6t EUR. Spains two largest lenders, BBVA and Banco Santander, have cumulative balance sheets of 1.75t EUR. Deutsche Bank and Commerzbank have cumulative balance sheets of 2.6t EUR. BNP and Societe Generale have cumulative balance sheets of 3.1t EUR. Imagine if the tier 1 capital of those banks had to be replaced. Could Spain add a 175b EUR bailout of its largest lenders to its budget? Could France add a 300b EUR bailout of two banks to its already ballooned deficit? For that matter, can Germany afford to bail out its banks? If Europe sounds like the America in 2008 to you bad loans culminating in big bank write-offs and a bailout well, youre right. The difference is that while the U.S recapitalized its banking system in part by raising funds at the national level (remember the 700b USD TARP?), we now know that the U.S. mostly paid for the bailout via the Fed, i.e. with printed money. During 2008 and 2009, the Fed increased the size of its balance sheet by 1.7t and opened as much as 4.5t in additional liquidity via its Term Auction Facility. While TARP represented roughly 5% of U.S. GDP in 2009, the Feds expenditures represented 35%. There is no way that the U.S. could have sustained that level of spending by borrowing in public markets, and neither can Europe. Borrowing enough money to recapitalize European banks and fund the borrowing needs of countries frozen out of credit markets would increase the debt burdens of all of the European countries to untenable levels Germany included. Alas, Germany, fuelled by what we call Weimar memories, refuses to allow the ECB to monetize costs of recapitalizing Europes banking system. Its our considered view that until Germany prints, Europe will remain highly unstable and European financial crises will episodically disrupt financial markets and indeed the global economy. No exit Among the inevitable conclusions of this analysis is that forcing weak members to leave the euro will not alleviate any problems as the issues are as much core as peripheral. German and French banks are in fact much more of a problem then tax recidivism in Greece. Another conclusion, and one that is more investable, is that the monetization of Europes debts is inevitable. There are two very straight-forward investment themes here: a) However the Euro crisis evolves, it will be highly negative for European financial companies, the recapitalization of which will be by necessity highly dilutive. At the same time, if such recapitalizations are to occur, they will present opportunities, as proven by the experience of American banks in the first half of 2009. b) Printing of trillions of euros will be highly negative for the euro against essentially any other currency. The euro is trading above fair value as measured both by interest rate parity models and Purchasing Power Parity. It is unimaginable that this situation can outlast meaningful quantitative easing by the ECB. But perhaps the most important conclusion is that many of the foundational tenets of contemporary European society need to be reconsidered if both monetary and fiscal union are to be maintained. This crisis is too severe not to result in fundamental changes to the social contract in Europe, and we watch with a mix of interest and trepidation as to how society will adapt and react to the medicine required to ward off Europes financial flu.

HB & DZ

Page 4

Review & Outlook December 7,2011 Volume 35, Number 12

You might also like

- Paper - The Fiscal Crisis in Europe - 01Document9 pagesPaper - The Fiscal Crisis in Europe - 01290105No ratings yet

- The Reform of Europe: A Political Guide to the FutureFrom EverandThe Reform of Europe: A Political Guide to the FutureRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- Q&A: Greek Debt Crisis: What Went Wrong in Greece?Document7 pagesQ&A: Greek Debt Crisis: What Went Wrong in Greece?starperformerNo ratings yet

- Kinnaras Capital Management LLC: April 2010 Market CommentaryDocument4 pagesKinnaras Capital Management LLC: April 2010 Market Commentaryamit.chokshi2353No ratings yet

- Responding to the European Sovereign Debt CrisisDocument25 pagesResponding to the European Sovereign Debt CrisisJJ Amanda ChenNo ratings yet

- Guide To The Eurozone CrisisDocument9 pagesGuide To The Eurozone CrisisLakshmikanth RaoNo ratings yet

- The Europea Debt: Why We Should Care?Document4 pagesThe Europea Debt: Why We Should Care?Qraen UchenNo ratings yet

- 1 DissertationsDocument11 pages1 DissertationsKumar DeepanshuNo ratings yet

- Lessons From The Global Financial Crisis: What Has Happened?Document11 pagesLessons From The Global Financial Crisis: What Has Happened?palashndcNo ratings yet

- Debt CrisisDocument8 pagesDebt CrisisUshma PandeyNo ratings yet

- European UpdateDocument5 pagesEuropean UpdatebienvillecapNo ratings yet

- What Is The European DebtDocument32 pagesWhat Is The European DebtVaibhav JainNo ratings yet

- Criticart - Young Artists in Emergency: Chapter 1: World Economic Crisis of 2007-2008Document17 pagesCriticart - Young Artists in Emergency: Chapter 1: World Economic Crisis of 2007-2008Oana AndreiNo ratings yet

- Vinod Gupta School of Management, IIT KHARAGPUR: About Fin-o-MenalDocument4 pagesVinod Gupta School of Management, IIT KHARAGPUR: About Fin-o-MenalFinterestNo ratings yet

- Tie w12 SinnDocument3 pagesTie w12 SinnTheodoros MaragakisNo ratings yet

- The European Debt Crisis: HistoryDocument7 pagesThe European Debt Crisis: Historyaquash16scribdNo ratings yet

- The Eurozone in Crisis:: Professor Assaf RazinDocument59 pagesThe Eurozone in Crisis:: Professor Assaf RazinUmesh YadavNo ratings yet

- Euro Debt-1Document7 pagesEuro Debt-1DHAVAL PATELNo ratings yet

- RMF July UpdateDocument12 pagesRMF July Updatejon_penn443No ratings yet

- Sovereign Debt: A Modern Greek Tragedy Greek Tragedy: Dr. Christopher WallerDocument44 pagesSovereign Debt: A Modern Greek Tragedy Greek Tragedy: Dr. Christopher WallerJay H. ManiNo ratings yet

- Eurozone Crisis 2.0Document1 pageEurozone Crisis 2.0mrwonkishNo ratings yet

- European Economic Outlook: No Room For Optimism: June2014 1Document2 pagesEuropean Economic Outlook: No Room For Optimism: June2014 1pathanfor786No ratings yet

- EU Crisis and Its Effect S: Presented by Leon Emre Taha LukeDocument10 pagesEU Crisis and Its Effect S: Presented by Leon Emre Taha Lukeemre tunaNo ratings yet

- Eurozone Debt CrisisDocument19 pagesEurozone Debt CrisisVarsha AngelNo ratings yet

- Is the Euro Zone SinkingDocument8 pagesIs the Euro Zone SinkingAbhishek AgrawalNo ratings yet

- Greek Financial Crisis May 2011Document5 pagesGreek Financial Crisis May 2011Marco Antonio RaviniNo ratings yet

- Summary and Analysis of The Euro: How a Common Currency Threatens the Future of Europe: Based on the Book by Joseph E. StiglitzFrom EverandSummary and Analysis of The Euro: How a Common Currency Threatens the Future of Europe: Based on the Book by Joseph E. StiglitzRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (3)

- Bob Chapman The Economic Crisis in Europe Unpayable Debts Impending Financial Insolvency 15 10 2011Document3 pagesBob Chapman The Economic Crisis in Europe Unpayable Debts Impending Financial Insolvency 15 10 2011sankaratNo ratings yet

- National Law Institute University: Greek Sovereign Debt CrisisDocument15 pagesNational Law Institute University: Greek Sovereign Debt Crisisalok mishraNo ratings yet

- Greek Debt Crisis "An Introduction To The Economic Effects of Austerity"Document19 pagesGreek Debt Crisis "An Introduction To The Economic Effects of Austerity"Shikha ShuklaNo ratings yet

- John Mauldin Weekly 10 SeptemberDocument11 pagesJohn Mauldin Weekly 10 Septemberrichardck61No ratings yet

- The Greece Meltdown: An Effort To Understand Its Impact On Euro Union and The WorldDocument12 pagesThe Greece Meltdown: An Effort To Understand Its Impact On Euro Union and The WorldarpitloyaNo ratings yet

- Essential Reading 5Document16 pagesEssential Reading 5kevinballesterosNo ratings yet

- Debt Crisis in GreeceDocument6 pagesDebt Crisis in Greeceprachiti_priyuNo ratings yet

- Italy will be Europ1 (1)Document3 pagesItaly will be Europ1 (1)quyên NguyễnNo ratings yet

- 2010 June What You Get For 750bn JSDocument7 pages2010 June What You Get For 750bn JSmanmohan_9No ratings yet

- On The Crisis and How To Overcome It: Part OneDocument13 pagesOn The Crisis and How To Overcome It: Part Oneampb2012No ratings yet

- Where Is The ECB Printing Press?Document7 pagesWhere Is The ECB Printing Press?richardck61No ratings yet

- Greece's Financial Crisis and Debt Problems ExplainedDocument4 pagesGreece's Financial Crisis and Debt Problems Explainedlubnashaikh266245No ratings yet

- The Independent SolutionDocument2 pagesThe Independent SolutionAdriana DhaniyahNo ratings yet

- Greece Crisis Report</TITLEDocument14 pagesGreece Crisis Report</TITLESmeet ShahNo ratings yet

- What Caused The Euro CrisisDocument2 pagesWhat Caused The Euro CrisisCharlieFellNo ratings yet

- Investment Compass - Summer 2011 - Europe, Earnings, and ExpectationsDocument4 pagesInvestment Compass - Summer 2011 - Europe, Earnings, and ExpectationsPacifica Partners Capital ManagementNo ratings yet

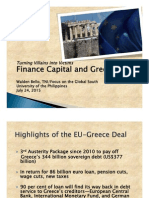

- W. Bello: Turning Villains Into Victims Finance Capital and GreeceDocument35 pagesW. Bello: Turning Villains Into Victims Finance Capital and GreeceGeorge PayneNo ratings yet

- 82115595-10 Countries With The Most Debt in The World 21-2-2012 PDFDocument10 pages82115595-10 Countries With The Most Debt in The World 21-2-2012 PDFAthanassiosNo ratings yet

- Eurozone Debt Crisis: Causes, Timeline, Extent of The Crisis, How It Is Being Addressed and How It'Ll Affect UsDocument15 pagesEurozone Debt Crisis: Causes, Timeline, Extent of The Crisis, How It Is Being Addressed and How It'Ll Affect UsShivani SharmaNo ratings yet

- The Spectre of Eurozone DeflationDocument2 pagesThe Spectre of Eurozone DeflationsignalhucksterNo ratings yet

- European Sovereign-Debt Crisis: o o o o o o o oDocument34 pagesEuropean Sovereign-Debt Crisis: o o o o o o o oRakesh ShettyNo ratings yet

- Eurozone Debt Crisis: Lessons for IndiaDocument12 pagesEurozone Debt Crisis: Lessons for Indiashivani mehtaNo ratings yet

- Eurozone CrisisDocument22 pagesEurozone CrisisSazal MahnaNo ratings yet

- Italy at The Half Way Mark 2012Document36 pagesItaly at The Half Way Mark 2012Mazziero ResearchNo ratings yet

- Europe Debt Crisis Impact on Global EconomyDocument16 pagesEurope Debt Crisis Impact on Global EconomyHồng NhungNo ratings yet

- Eurozone Paper FinishedDocument16 pagesEurozone Paper Finishedpreetdesai92No ratings yet

- European Debt CrisisDocument3 pagesEuropean Debt CrisisVivek SinghNo ratings yet

- Greek Crisis Questions Honest AnswersDocument7 pagesGreek Crisis Questions Honest AnswersDimitrisNo ratings yet

- European Debt Crisis 2009 - 2011: The PIIGS and The Rest From Maastricht To PapandreouDocument39 pagesEuropean Debt Crisis 2009 - 2011: The PIIGS and The Rest From Maastricht To PapandreouAnuj KantNo ratings yet

- Case Study LFGHRDocument10 pagesCase Study LFGHRAshish NandaNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals of the Indian Capital MarketDocument37 pagesFundamentals of the Indian Capital MarketBharat TailorNo ratings yet

- Meaning of Business EnvironmentDocument2 pagesMeaning of Business EnvironmentRandeep kourNo ratings yet

- EMBA Applied Value Investing (Ajdler) SP2016Document3 pagesEMBA Applied Value Investing (Ajdler) SP2016darwin12No ratings yet

- SolutionDocument3 pagesSolutionmaiaaaaNo ratings yet

- Concepts of Quality, Total Quality and Total Quality ManagementDocument3 pagesConcepts of Quality, Total Quality and Total Quality Managementbshm thirdNo ratings yet

- Star ModelDocument2 pagesStar ModelhrgatorNo ratings yet

- Better Business 5th Edition Solomon Solutions ManualDocument26 pagesBetter Business 5th Edition Solomon Solutions ManualChelseaHernandezbnjf100% (51)

- Bank of America Merrill Lynch DossierDocument5 pagesBank of America Merrill Lynch DossierJamesNo ratings yet

- Meaning: Sustainable Development Goals (SDGS) Paris Climate AgreementDocument11 pagesMeaning: Sustainable Development Goals (SDGS) Paris Climate AgreementridhiNo ratings yet

- SAP FI-AA Configuration GuideDocument12 pagesSAP FI-AA Configuration Guidebhushan130100% (1)

- Handouts 04.04 - Part 3Document3 pagesHandouts 04.04 - Part 3John Ray RonaNo ratings yet

- ReportDocument2 pagesReportumaganNo ratings yet

- Tundra Services CompanyDocument1 pageTundra Services CompanyBluesinhaNo ratings yet

- INTL 725 - 102 International Business ManagmentDocument11 pagesINTL 725 - 102 International Business Managmentakhil betigeriNo ratings yet

- Corporate RestructuringDocument6 pagesCorporate RestructuringPROFESSION BECOMERNo ratings yet

- Basic Concepts Residential StatusDocument35 pagesBasic Concepts Residential StatuszaidansarizNo ratings yet

- Strategic Analysis On SonyDocument37 pagesStrategic Analysis On Sonylavkush_khannaNo ratings yet

- Perfect CompititionDocument35 pagesPerfect CompititionAheli Mukerjee RoyNo ratings yet

- May - August 2020 Exam Timetable FinalDocument24 pagesMay - August 2020 Exam Timetable FinalMARSHANo ratings yet

- IIT-Bombay WashU EMBA BrochureDocument28 pagesIIT-Bombay WashU EMBA Brochuregaurav_chughNo ratings yet

- Strategy Analysis & ChoiceDocument46 pagesStrategy Analysis & ChoiceUsama AkhlaqNo ratings yet

- President Uhuru Kenyatta's Speech During The Signing and Launching of The United Nations Development Assistance Framework (UNDAF)Document2 pagesPresident Uhuru Kenyatta's Speech During The Signing and Launching of The United Nations Development Assistance Framework (UNDAF)State House KenyaNo ratings yet

- MTD638Document20 pagesMTD638Ayla KowNo ratings yet

- Module 8. BLDG - EnhancingDocument12 pagesModule 8. BLDG - EnhancingCristherlyn DabuNo ratings yet

- World Rice Markets and Trade ReportDocument13 pagesWorld Rice Markets and Trade ReportErneta Joya Hertinah SariNo ratings yet

- Exercise 12-8 Intangible AssetsDocument2 pagesExercise 12-8 Intangible AssetsJay LazaroNo ratings yet

- CLC Selecting HR MetricsDocument5 pagesCLC Selecting HR Metricsdreea_mNo ratings yet

- FDsetia 20150923pj8xfnDocument41 pagesFDsetia 20150923pj8xfnJames WarrenNo ratings yet

- Formation of A Sale of Goods ContractDocument2 pagesFormation of A Sale of Goods ContractSwastik GroverNo ratings yet