Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Earnings Management and Long-Run Stock Performance Following Private Equity Placements

Uploaded by

ProfessorAsim Kumar MishraOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Earnings Management and Long-Run Stock Performance Following Private Equity Placements

Uploaded by

ProfessorAsim Kumar MishraCopyright:

Available Formats

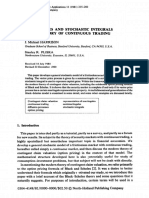

Rev Quant Finan Acc (2010) 34:225245 DOI 10.

1007/s11156-009-0129-8 ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Earnings management and long-run stock performance following private equity placements

De-Wai Chou Michael Gombola Feng-Ying Liu

Published online: 31 May 2009 Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2009

Abstract We investigate whether the documented earnings management preceding public equity offerings applies to private placements of equity. We also investigate whether earnings management can help explain long-run stock performance following private placements. Our main ndings are: (1) little evidence of upward earnings management around private equity placements, and (2) little predictive power of abnormal accruals for long-run stock performance following private equity placements. These results suggest that earnings management is not responsible for post-offering underperformance, if any, for rms issuing equity privately. Our results are robust to two alternative measures of earnings management and three measures of abnormal returns estimated over two sample periods. Keywords Earnings management Private equity issues Long-run performance

JEL Classication G32

1 Introduction Evidence of earnings management has been documented for a variety of public equity offerings. It has been shown around IPOs by Teoh et al. (1998a) and DuCharme et al. (2004), around SEOs by Teoh et al. (1998b), Rangan (1998), and Jo and Kim (2007) and around reverse LBOs (i.e., second IPOs) by Chou et al. (2006). Furthermore, these studies

D.-W. Chou Yuan-Ze University, Taoyuan, Taiwan, ROC e-mail: dwchou@saturn.yzu.edu.tw M. Gombola (&) Drexel University, Philadelphia, PA, USA e-mail: gombola@drexel.edu F.-Y. Liu Rider University, Lawrenceville, NJ, USA e-mail: liuf@rider.edu

123

226

D.-W. Chou et al.

provide evidence of a negative relation between earnings management and post-issue stock return performance. The evidence leads to a conclusion that earnings management can explain, at least in part, stock price performance following public equity issuance. Unlike IPOs and SEOs, earnings management around private placements of equity might be more limited. Managers of rms issuing private equity might have limited opportunity to manage earnings due to limited information asymmetry between informed private placement investors and managers of rms issuing equity privately. Managers might also have limited time to manage earnings prior to a private placement when the private placement is arranged quickly in order to raise unforeseen funds. Managers of rms issuing equity privately might still practice earnings management, just like IPOs and SEOs, and choose to compensate informed private placement investors, who can see through earnings management, with substantial discounts of the market price.1 Outside investors, who cannot detect earnings management, could be deceived by the private placement announcement. When earnings management is later reversed, these outside investors could be disappointed by the lower-than-expected earnings, leading to poor long-run stock price performance. This view is consistent with the investor overoptimism hypothesis presented by Teoh et al. (1998a) for public offerings and applied to private placements by Hertzel et al. (2002). Teoh et al. (1998a, b) argue that earnings management could be used as a device to heighten investor optimism about the performance and future prospects of issuing rms. If investor optimism is heightened in the presence of earnings management, then we should expect a positive relation between the extent of earnings management at the private placement and the magnitude of post-offering underperformance following private equity placements. Hertzel et al. (2002) report underperformance for their sample of private equity placements during the period between1980 and 1996. The objective of this study is to investigate whether managers of rms issuing private equity manage earnings upward and whether the earnings management explanation for long-run stock performance of public issues also holds for private issues. We measure earnings management by two proxies, discretional current accruals (DCA) estimated by the modied Jones (1991) model and DCA estimated based on the performance-matched approach espoused by Kothari et al. (2005). We do not nd signicant evidence of earnings management for our overall sample of equity private placements from either measure of DCA. We nd that median and mean DCA of the issue year are positive, but not statistically signicant for either earnings management proxy. The median (mean) estimate of DCA from the modied Jones (1991) model is 0.05% (2.94%) of total assets, which is smaller than the median (mean) DCA of 4.01% (9.95%) reported by Teoh et al. (1998a) for IPOs. DCA estimates from the performance-matched approach are larger, but are still not statistically signicant. Our ndings are consistent with the view that managers of rms issuing equity privately generally have limited opportunity or incentive to manage earnings upwards around the time of the private issue. Although the overall sample does not provide evidence of signicant earnings management, it remains possible that long-run stock performance following private placements is cross-sectionally related to earnings management. To examine the cross-sectional relation between earnings management and post-issue stock returns, we rst stratify our sample into quartiles based on the magnitude of discretionary current accruals (DCA) in

1

The average private discounts reported by Hertzel and Smith (1993) and Hertzel et al. (2002) are 20.1% and 16.5%, respectively. This compares to 3.0% for SEO discounts reported in Mola and Loughran (2004).

123

Earnings management and long-run stock performance

227

the issue year, ranging from the most aggressive quartile (i.e., with the largest discretionary current accruals) to the most conservative quartile (i.e., with the smallest DCA). To control for size effects, we construct DCA quartiles that are composed of rms with similar rm size. Our preliminary results show that rms in the more aggressive earnings management quartiles (with higher DCA) experience greater post-offering underperformance. Our further results show that after controlling for rm size across DCA quartiles, evidence of greater underperformance for more aggressive earnings management quartiles disappears. Such evidence points to the importance of controlling for rm size when examining stock price effect of private placements. Further examination of the relation between earnings management and long-term stock performance following private placements is performed by cross-sectional regressions of 3-year stock returns using DCA as an independent variable while controlling for rm size and book-to-market. To avoid potential problems from overlapping multi-year stock returns, we also conduct rolling regressions of monthly stock returns following a procedure developed by Fama and MacBeth (1973). Neither of these regression models provides evidence that DCA is a signicant factor explaining post-issue stock returns for the overall sample. The coefcient for the DCA variable is negative, but never statistically signicant. We also compare stock performance following private placements of equity for our sample period between 1980 and 2000 with that during the shorter 19801996 period used by Hertzel et al. (2002). We nd that the two sample periods differ considerably in the degree of underperformance. Consistent with Hertzel et al. (2002), our results for the 19801996 period show considerable evidence of underperformance following private placements, according to any of the three abnormal return measures employed, buy-andhold abnormal returns, abnormal returns relative to the Fama and French (1993) threefactor model and the four-factor model. However, over the longer period from 1980 to 2000, evidence of underperformance is limited to buy-and-hold abnormal returns. Abnormal returns estimated from the threefactor and four-factor models do not provide signicant evidence of underperformance. Although stock performance following private placements differs across the two time periods, our results provide no evidence of a cross-sectional relation between stock price performance and discretionary accruals, regardless of the time period. Our results showing that underperformance following private placements is not related to earnings managements offer another example of the uniqueness of private equity placements. Earlier, Hertzel and Smith (1993) and Wruck (1989) demonstrate a positive announcement effect that is opposite of the negative announcement effect shown for public equity offerings. Similarly, Goh et al. (1999) show upward earnings forecast revisions for private placements that are opposite to those for public equity offerings. The uniqueness of private placements might imply that explanations for post-offering underperformance following public equity offering might not transfer to private equity placements. Instead, researchers might need to look at the unique characteristics of companies that offer equity privately in order to explain their post-offering stock performance.

2 Earnings management and private placements of equity In contrast to public equity issues, which are underwritten, registered with the Securities Exchange Commission (SEC) and sold to a large number of investors, private placements of equity are not necessarily registered with the SEC and typically negotiated individually with

123

228

D.-W. Chou et al.

a limited number of prospective investors. These investors can be sophisticated institutional investors or accredited individual investors, who expend considerable effort in researching the earnings power and prospects of rms. Their research could include private information not available to outside investors. Therefore, information asymmetry between investors and managers of rms issuing equity privately is more limited than for public offerings. Private placements also differ from public offerings in their speed and exibility. A private placement can be arranged quickly in order to raise unforeseen required funds and might not allow managers sufcient time to manage earnings prior to the offering. Personal negotiations between buyer and seller also allow tailoring the placement to meet the specic needs of the buyer and seller. Brophy et al. (2004) point out that a substantial proportion of equity private placements in their sample are structured so that the ultimate offer price is determined after the offering is announced. For structured offerings, preoffering earnings management could result in a lower offering price. In the information-signaling model presented by Hertzel and Smith (1993), a signal of undervaluation is conveyed by the purchase and commitment by private placement investors together with the managerial choice of issuing equity privately. If private placement of equity reects managerial choice of issuing equity rather than forgoing a protable investment, it rules out the possibility that managers take advantage of investor optimism at the time of the issue. Even if accredited individual investors participate in the placement, the presence of sophisticated institutional investors will mitigate the problem of information asymmetry. Furthermore, one class of accredited individual investors includes ofcers and directors of the issuing rm, for whom there exists virtually no information asymmetry. Therefore, a managerial attempt to mislead the sophisticated investors participating in the private placement through earnings management is unlikely in the Hertzel and Smith (1993) information signaling model. Wruck (1989) argues that more concentrated ownership resulting from private placements of equity would lead to monitoring and incentive alignment effects due to the involvement of private placement investors, who are expected to provide monitoring and expert advice in exchange for substantial discounts from current market value. The monitoring and alignment effects could increase efciency and future performance. Since the purchasers are quasi-management insiders, they would have no incentive to mislead themselves with earnings management. A view opposite to the implication of the monitoring hypothesis presented by Wruck is expressed by Barclay, Holderness and Sheehan (2004). They posit that private placements are often arranged between managers and passive or friendly investors who do not generate conicts with managers. The investors are compensated for their passivity through the discounts offered in the private placement. Rather than offering monitoring and discipline, the passive investors help to entrench managers. Therefore, earnings management could be known to managers and passive investors, but not to uninformed external investors. Investor optimism prior to an offering followed by post-offering disappointment is described by Teoh et al. (1998a) in their discussion of the effects of earnings management. Earnings management involves borrowing earnings from future periods to show better current earnings. With higher current earnings shown due to earnings management, investors become more optimistic about the future prospects of the rm. However, when the borrowed earnings result in lower future earnings, investors become disappointed. Teoh and Wong (2002) nd that, following IPOs and SEOs, not only can investors be misled by earnings management but so can analysts. Analyst forecasts of earnings are based on extrapolations of reported earnings that are managed upwards by high levels of

123

Earnings management and long-run stock performance

229

accruals. When these accruals are reversed after IPOs and SEOs, analysts are forced to revise downward their earnings forecasts. Teoh and Wong nd that accounting accruals can predict analyst forecast errors and that the forecast errors predicted from accruals are signicantly associated with post-issue stock performance for IPOs and SEOs. Their ndings of analyst credulity for earnings management indicates that trained and wellinformed analysts can be misled by earnings management practices. If analysts could be misled by earnings management then perhaps other well-informed investors, such as investors in private placements, could also be misled by earnings management practices. Jo and Kim (2007) show that earnings management is inversely related to disclosure frequency. Firms with greater disclosure frequency underperform to a lesser extent after an SEO. Firms that disclose infrequently, but then increase disclosure frequency immediately before an offering also manage earnings aggressively before the offering. Such behavior is consistent with an attempt to publicize the stock in order to generate investor optimism and a higher stock price. The operating performance and rm size information presented by Hertzel et al. (2002) suggests that rms in their sample are in desperate need of operating funds and are dangerously close to NASDAQ NMS de-listing standards. Under these circumstances issuing rms could be desperate to obtain external capital, and are willing to accept last resort nancing in a private placement. Since numerous examples of accounting fraud have been shown by rms desperate to maintain their current stock prices, the managers of rms issuing private placements also have ample motivation (or desperation) to engage in earnings management to maintain the stock price and obtain badly-needed external capital.

3 Sample and methodology 3.1 The sample Our initial sample of private placements of equity was identied by a keyword search of Dow Jones News Service for articles published in Dow Jones Newswires from 1980 to 2000. This keyword search identied more than 1,200 articles that were individually read in order to determine the initial sample. Our sample includes only private placements of common stock or common stock with warrants. We exclude private placements of common stock that contain other types of securities such as debt securities or convertible preferred stock since the focus of our study is on private placements of equity. The initial sample includes 782 private placements of equity. We keep only the rst of multiple private placements by the same rm within a 3-year period to avoid overlapping return calculations for the same rm. This exclusion reduces the sample by exactly 100 private placements. The further exclusion of rms without available data in the CRSP monthly returns le reduces the sample size to 562 placements. The sample is further reduced to 289 private placements of equity issued by rms with available Compustat data for computation of discretionary current accruals, our proxy for earnings management. We use the sample of 289 private placements for earnings management analyses.2

2

In our nal sample of 289 rms, 286 rms have complete return data for the 36 months following the placement. For the three exceptions, one rm has available data for 35 months with the last month missing, one rm has available data for 30 months with the last 6 months missing, and one rm has available 9 months of data with the remaining 27 months missing.

123

230

D.-W. Chou et al.

In Table 1, Panel A reports the time distribution of the sample with available CRSP data and the sample with available CRSP and Compustat data. The distribution of the two samples is very similar across the sample period. Private placements are clustered somewhat in time with a large number of placements in 1993 and again in 2000. The largest number of private placements in a single year is observed for 2000, when stock prices were at high levels. The high level of private placement activity during 2000 provides motivation to extend the sample period beyond the 19801996 sample period used by Hertzel et al. in order to consider the offerings after that period. Consistent with the tendency of rms issuing private placements to be small in size, rms traded on the NYSE or AMEX comprise 15% of either the 19801996 or 19802000 sample, and 85% of either sample is made up of NASDAQ-traded rms. The proportion of

Table 1 Time distribution and rm characteristics of private placements of equity sample from 1980 to 2000 Panel A: Time distribution of private equity placements sample Fiscal year The sample with available CRSP data The sample with available CRSP and compustat data Frequency 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 Total 8 7 11 19 12 33 27 28 29 29 20 28 38 54 29 33 26 28 25 21 57 562 % 1.42 1.25 1.96 3.38 2.14 5.87 4.80 4.98 5.16 5.16 3.56 4.98 6.76 9.61 5.16 5.87 4.63 4.98 4.45 3.74 10.14 100.00 Frequency 4 1 4 7 4 9 12 14 14 20 8 9 15 30 15 19 17 18 16 15 38 289 % 1.38 0.35 1.38 2.42 1.38 3.11 4.15 4.84 4.84 6.92 2.77 3.11 5.19 10.38 5.19 6.57 5.88 6.23 5.54 5.19 13.15 100.00

Panel B: Summary statistics of rm characteristics for the sample of private placements of equity Market value of equity ($million) Mean Median 156.57 41.71 Book-to-market 0.31 0.24 Total assets ($million) 77.77 18.30

123

Earnings management and long-run stock performance

231

NASDAQ companies (85%) in both samples is slightly higher than the proportion (79%) in the sample used by Hertzel et al. (2002). Panel B of Table 1 reports rm characteristics of our sample. Both our sample and the sample used by Hertzel et al. are skewed toward small growth rms with low book-tomarket ratios.3 The mean (median) book-to-market ratio is 0.31 (0.24). To the extent that a book-to-market ratio less than one indicate growth opportunities, the book-to-market values indicate that our sample is tilted toward growth rms. The mean market value of equity for rms in our sample is $156.5 million. The median market value of equity for our sample is $41.7 million, which is below the current minimum of $50 million necessary to maintain listing in the NASDAQ National Market System.4 Given the extreme small size of rms offering private placements, control for rm size is essential in analyzing performance. 3.2 Measuring abnormal accruals If earnings management is employed to increase earnings, the increase can be accomplished through accelerating recognition of revenues or delaying recognition of expenses.5 Differences between revenues recognized and cash received or between expenses recognized and cash expenditures create accruals or deferrals. Since the basis of earnings management lies in the difference between cash ows and earnings, analyzing accruals, which is the difference between cash ows and earnings, provides insight into earnings management practices. Because short-term accruals are more easily subject to management, the focus of our study, like that of studies such as Teoh et al. (1998a, b), is on shortterm accruals. Computation of accruals in our study is based on denitions of accruals by Perry and Williams (1994) that are also used by Teoh et al. (1998a, b).6 Perry and Williams (1994) compute total accruals as the change in non-cash working capital (excluding current maturities of long-term debt less total depreciation expense for the current period). Their denition is similar to Jones (1991); differing by the exclusion of adjustment for income taxes. Perry and Williams (1994) include income tax in their model because the income tax accrual could be an important component of an earnings management strategy. Earnings management is revealed in an abnormal level of accruals relative to the rms business activity. A regression model is used to estimate the expected accruals. Deviations from expected accruals could be attributed to earning management. Teoh et al. (1998a, b) call these deviations DCA. Expected accruals, which can also be called nondiscretionary current accruals, are estimated from a cross-sectional regression of current accruals in a given year on the change in sales. This regression uses an estimation sample that includes all rms with the same two-digit SIC code as the private equity issuer, but exclude the issuer and

3

The industry distribution of our sample, not reported, is very similar to that reported by Hertzel et al. (2002), with the top nine SIC/industry codes for our sample rms the same as theirs. In reviewing the FACTIVA issuance reports, the statement that the offering allowed the rm to maintain NMS listing was observed frequently. Earnings management can also be accomplished through changes in accounting methods, and changes in capital structure such as debt defeasance and debt-equity swaps.

6 Teoh et al. (1998a) provide a detailed description of the denition and construction of accrual measures in their study. The description includes the specic Compustat items used to construct accrual measures. We follow their description and denition in the construction of our accrual estimates.

123

232

D.-W. Chou et al.

other private equity issuers. In addition to the SIC lter, non-ordinary common stocks, such as ADRs, closed-end funds and REITs, are removed from the estimation sample. To reduce heteroskedasticity in the data, we scale all variables in the regression by total assets. We also use an alternate DCA measure proposed by Kothari et al. (2005). Kothari et al. argue that the traditional discretionary accrual models, such as the modied Jones (1991) model, might be mis-specied when applied to samples of rms with extreme performance. The traditional models over-estimate accruals for rms with extreme good performance and under-estimate accruals for rms with poor performance. To mitigate the problem of estimating accruals for rms in performance extremes, Kothari et al. propose a performance-matched approach to estimating abnormal accruals.7 Following Kothari et al. (2005), for each sample rm we identify a matched rm with the closest ROA of the issue year and the same two-digit SIC. Then, we estimate DCA following the method of Teoh et al. (1998a) described above for each of the sample rms and matched rms. Abnormal earnings management is dened as the difference between the DCA of the sample rm and the DCA of its matched rm. 3.3 Measuring long-run stock price performance Measuring long-run stock returns remains a controversial topic. Fama (1998) indicates that long-term returns are sensitive to the expected return model used to measure the abnormal returns and the statistical tests conducted. We use three methods: (1) buy-and-hold abnormal return (BHAR) method, (2) the three-factor model of Fama and French (1993), and (3) a four-factor model, which includes the FamaFrench three factors and a momentum factor used by Carhart (1997). Ritter (1991) points out that the BHAR method provides an appropriate description of the return experience for investors, since investors do not rebalance their portfolios on a monthly basis, as implied by the Fama and French (1993) approach. Instead, they hold on to their shares for a longer time period. Longer holding periods are particularly appropriate for investors in private placements since these investors may not be able to re-sell their shares quickly after the offering, but can only sell to other qualied investors or wait until the shares become registered with SEC for public trading. Among others, Fama (1998) points out that the BHAR method can be problematic because the long-term buy-and-hold returns distribution is skewed. To address the skewness problem, we test statistical signicance of the buy-and-hold abnormal return by using a skewness-adjusted t-statistic, which is derived by Hall (1992) and similar to the procedure described in Lyon et al. (1999), in addition to the conventional cross-sectional t-statistic. Mitchell and Stafford (2000) show that the cross-dependence problem of overlapping event-rm stock returns can inate t-statistics of BHAR. To address the crosssectional dependence problem, we use the monthly calendar-time portfolio approach, recommended by Fama (1998) and Mitchell and Stafford (2000), to estimate both the three-factor model and the four-factor model.

They nd that matching on the rms return on assets (ROA) tends to be better than matching on other variables.

123

Earnings management and long-run stock performance

233

3.3.1 Buy-and-hold return method We estimate buy-and-hold abnormal returns relative to a benchmark as follows: BHARi

T Y t1

1 Ri;t

T Y t1

1 Rbenchmark;t

where Ri,t is the monthly return for rm i in month t, and Rbenchmark,t is the monthly return for the benchmark (i.e., the control rm) in month t. We calculate buy-and-hold returns for the 3-year period beginning the month following the issue month, or until either the sample or control rm delists, whichever is sooner. In calculating buy-and-hold abnormal returns, we use a size-and-book-to-market-matched sample as the benchmark. The size and book-to-market control sample approach provides an appropriate benchmark for two reasons. First, our sample consists of rms that are relatively smaller in size, with 85% of the sample rms traded on the NASDAQ, as would be expected in a private placement sample. Secondly, small rms and rms with low book-to-market ratios tend to produce lower stock returns (e.g., Fama and French 1992, Barber and Lyon 1997). We follow the procedure suggested by Lyon et al. (1999) in constructing the size and book-to-market matched sample. We rst identify all rms in the CRSP database with a market value of equity between 70% and 130% of the market value of equity of a sample rm. Then, from this set of rms, we choose the rm with the book-to-market closest to that of the sample rm. Firm size is dened as the total market value of equity of the rm (i.e., closing stock price multiplied by the number of shares outstanding) measured on the rst day of the issue month. Book-to-market is dened as the rms book value of equity divided by its market value of equity, measured at the scal year end prior to the equity issue. To avoid a small matched sample, if the book-to-market ratio is not available for the issuing rm in Compustat, we match only by size using CRSP data. 3.3.2 The calendar time three-factor model and four-factor model We estimate abnormal stock returns based on the three-factor model of Fama and French (1993) using calendar-time portfolio approach. Portfolios of private placements are formed monthly, in calendar time. The regression model is: Rp;t Rft ap bp Rmt Rft sp SMBt hp HMLt ep;t ; 2

where Rp,t is the return on portfolio p in month t, Rft is the return on one-month treasury bills in month t, Rmt is the return on a market index in month t, SMBt is the difference in the returns of a portfolio of small and big stocks in month t, and HMLt is the difference in the returns of a portfolio of high book-to-market stocks and low book-to-market stocks in month t, and ep,t is the error term for portfolio p in month t. The estimate of the intercept coefcient (ap) provides a test of the null hypothesis of zero average abnormal return. We also estimate abnormal stock returns based on a four-factor model, which includes the three factors of the Fama and French (1993) model and a momentum factor used by Carhart (1997), using calendar-time portfolio approach. Portfolios of private placements are formed monthly, in calendar time. The regression model is: Rp;t Rft ap bp Rmt Rft sp SMBt hp HMLt pp PR1YRt ep;t 3

123

234

D.-W. Chou et al.

where Rp,t, Rft, Rmt, SMBt, and HMLt are dened as in Eq. 2, PR1YRt is the difference in the returns of a portfolio of prior-year high return stocks and prior-year low return stocks in month t, and ep,t is the error term for portfolio p in month t. The intercept coefcient (ap) provides a test of the null hypothesis of no abnormal performance.

4 Results 4.1 Discretionary current accruals around private placements of equity Table 2 reports DCAs estimated by the modied Jones (1991) model and by the Kothari et al. (2005) performance-matched method for the 5 years surrounding private placements of equity in our sample in Panel A. Summary statistics of rm characteristics for DCA quartiles and size-equivalent DCA quartiles are presented in Panels B and C, respectively. As shown in Panel A, the mean DCA for the issue year is 2.94% of total assets, which is not statistically signicant (p-value = 0.14). The mean DCA for our sample is about one-fourth of the mean DCA of 9.95% for IPOs reported by Teoh et al. (1998a). The median DCA for the placement year is 0.05% of total assets, which is positive but not statistically signicant (p-value = 0.51). In contrast, the median DCA for the issue year of IPOs reported by Teoh et al. (1998a) is 4.01% of total assets. None of the other years surrounding the placement shows a signicant, positive mean or median value for DCA. The only statistically signicant DCA value is negative, and occurs for the second year after the offering. Performance-matched estimates of discretionary current accruals are larger than modied Jones (1991) model estimates, but are still not statistically signicant. The median performance-matched DCA are several times larger than the modied Jones model DCA, but are not signicant. The mean performance-matched DCA are approximately the same size as the modied Jones DCA and do not approach statistical signicance. None of the years before or after the offering shows a signicant mean or median performance-matched DCA, either positive or negative.8 Although Panel A of Table 2 shows no statistically signicant evidence of earnings management for our full sample, the positive sign suggests some further investigation whether a few rms might still practice earnings management. We follow Teoh et al. (1998a) in classifying rms in quartiles according to issue-year DCA and then examine whether the subset of rms practicing more aggressive earnings management suffers greater post-offering underperformance. As shown in Panel B, the distribution of DCA across quartiles is relatively symmetrical around zero, with two quartiles displaying positive mean and median DCA and two quartiles displaying negative mean and median DCA. The most aggressive quartile has mean DCA of 35.03% of total assets, median DCA of 18.24% and a minimum DCA of 8.04%. Although median and mean DCA are large for the most aggressive quartile, they are still much smaller than corresponding DCA values for the most aggressive quartile of IPO rms. Teoh et al. (1998a) show the most aggressive DCA quartile of IPO rms has a mean DCA of 53.92%, a median of 39.76% and a minimum DCA of 18.5%. Results in Panel B show that there is no specic pattern for either rm size or book-tomarket across DCA quartiles. Median and mean values of rm size are smallest for Quartile 1 and largest for Quartile 3. Median and mean book-to-market are largest for

8

Remaining analysis employs the DCA estimates from the modied Jones (1991) model. Analysis using the performance-matched DCA estimates provides similar results.

123

Earnings management and long-run stock performance

235

Table 2 Discretionary current accruals (DCA) for private placements of equity and quartiles from 1980 2000 Panel A: Time-series distribution of discretionary current accruals Method DCA Year -2 Modied Jones Median p-value (Wilcoxon) Mean p-value (t-test) Performance-matched Median p-value (Wilcoxon) Mean p-value (t-test) 0.0038 (0.53) 0.0382 (0.33) 0.0128 (0.59) 0.0004 (0.98) -1 0.0010 (0.78) -0.0336 (0.29) -0.0009 (0.85) -0.0085 (0.75) 0 0.0005 (0.51) 0.0294 (0.14) 0.0217 (0.15) 0.0268 (0.20) 1 0.0024 (0.92) 0.0060 (0.66) 0.0198 (0.14) 0.0044 (0.83) 2 -0.0026 (0.03) -0.0064 (0.74) -0.0075 (0.34) -0.0299 (0.19)

Panel B: Summary statistics of rm characteristics in issue year for DCA quartiles Discretionary current accruals (DCA) Mean Most aggressive quartile (DCA C 0.0804) Quartile 2 (0.0005 B DCA \ 0.0804) Quartile 3 (-0.0709 B DCA \ 0.0005) 0.3503 0.0374 -0.0300 Median 0.1824 0.0372 -0.0270 -0.1671 Market value Book-to-market Median 0.18 0.30 0.24 0.14

Mean Median Mean 87.5 89.9 24.5 32.9 0.32 0.39 0.33 0.20

157.6 56.2 121.1 28.6

Most conservative quartile (DCA \ -0.0709) -0.2400

Panel C: Summary statistics of rm characteristics in issue year for size-equivalent DCA quartiles Discretionary current accruals (DCA) Mean Most aggressive quartile Quartile 2 Quartile 3 Most conservative quartile 0.3054 0.0458 -0.0310 -0.2064 Median 0.1459 0.0304 -0.0182 -0.1251 Market value Mean 246.2 117.4 123.6 132.2 Median 41.7 41.8 41.6 41.2 Book-to-market Mean 0.31 0.40 0.29 0.24 Median 0.20 0.26 0.21 0.15

Note: Panel A reports the time series distribution of discretionary current accruals (DCA) from year -2 to year 2 relative to the issue year (year 0). We follow the methodology in Teoh et al. (1998a) to estimate discretionary current accruals. The t-test is used for testing the mean of DCA and the Wilcoxon signed rank test is used for testing the median DCA. The benchmark rms used to estimate expected DCA are matched to sample rms by 2-digit SIC code. p-values appear in parentheses. Panel B reports summary statistics for DCA of the issue year (year 0), market value and book-to-market for DCA quartiles. Panel C reports summary statistics for DCA of the issue year (year 0), market value and book-to-market for size-equivalent DCA quartiles

Quartile 2, and smallest for Quartile 4. Although there is no specic pattern in rm size across DCA quartiles, the results indicate that rms in the most aggressive earnings management quartile (i.e., Quartile 1) are smallest in rm size. Small rms might afford a higher level of information asymmetry, enabling managers the opportunity to practice earnings management.9

9

For their IPO sample, Teoh et al. (1998a) also nd that rms in the most aggressive DCA quartile are smallest in rm size.

123

236

D.-W. Chou et al.

Our results shown in Panel B indicate a potential size effect for earnings management in rms offering private placements, with higher DCA for smaller rms. To minimize the effect of rm size on the relation between DCA and stock performance, we construct portfolios of rms similar in size but differing in DCA following the portfolio construction procedure described by Teoh et al. (1998a). First, we rank our sample rms by market capitalization on the issue day. Then, taking each contiguous set of four rms, we place the rm with the highest DCA into the rst (most aggressive) portfolio, the rm with the next highest DCA in the second portfolio, the third highest DCA in the third portfolio and the rm with the lowest DCA into the fourth (most conservative) portfolio. This procedure ensures that the size effect is minimized and only differences in DCA remain across the four portfolios. As shown in Panel C, the most aggressive DCA quartile has a mean DCA of 0.3054 and median DCA of 0.1459, which amount to 30% and 15%, respectively, of the offering rms total assets and much more than the offering rms earnings. By construction, the median market value of equity is very similar across all four DCA quartiles, ranging from a minimum median value of $41.2 million to a maximum of $41.7 million. The book-tomarket is also fairly consistent across these DCA quartiles with the mean ranging from 0.24 for the most conservative quartile to 0.40 for the second most aggressive quartile and the median ranging from 0.15 for the most conservative quartile to 0.26 for the second most aggressive quartile. The most aggressive quartile and quartile 3 are almost equal in the mean and median of book-to-market. 4.2 Long-term stock performance following private placements of equity Table 3 contains long-term returns following private placements of equity, with 3-year buy-and-hold abnormal returns (BHAR) presented in Panel A, monthly abnormal returns estimated from the three-factor model of Fama and French (1993) in Panel B, and monthly abnormal returns estimated from the four-factor model in Panel C. Each panel contains estimates of abnormal returns for the sample of private equity placements in the 1980 1996 period, and estimates for the sample in the longer 19802000 period. As shown in Panel A, BHARs relative to the book-to-market matched sample provide evidence of underperformance following a private placement for both the 19802000 and 19801996 periods. Three-year mean and median BHAR are negative and signicant, regardless of the time periods tested and the test statistics used. Also, the degree of underperformance shown for the 19801996 period is comparable to that shown by Hertzel et al. (2002) for the same sample period. Panel B reports the alpha coefcient estimated from the three-factor model of Fama and French (1993). For the 19801996 period, the alpha coefcient is negative and statistically signicant, which is consistent with the nding by Hertzel et al. (2002). The alpha coefcients of -0.0085 for value-weighted portfolios and -0.0084 for equally weighted portfolios are both signicant at the 0.01 level (t = -3.14 and -2.76, respectively). The alpha coefcients, which measure monthly abnormal returns, are equivalent of an implied 3-year abnormal returns of approximately -26% (=((1 - 0.0085)36 - 1) 9 100).10

10 The implied three-year abnormal return is calculated as (1 ? a)36 - 1.0, where alpha measures the monthly abnormal return.

123

Earnings management and long-run stock performance

237

Table 3 Post-issue 3-year buy-and-hold abnormal returns and average monthly abnormal returns relative to calendar-time three-factor model and four-factor model for the sample of 562 private placements of equity Panel A: 3-year buy-and-hold abnormal returns (BHAR) 19802000 period Mean Median Cross-sectional t-stat. Skewness-adjusted t-stat. Panel B: Calendar time three-factor model 19802000 period Value-weighted Alpha coefcient -0.0026 (-0.79) Equally weighted -0.0047 (-1.38) 19801996 period Value-weighted -0.0085 (-3.14)*** Equally weighted -0.0084 (-2.76)*** -20.88% -41.22% (-5.05)*** [-3.53]*** 19801996 period -16.21% -37.77% (-3.31)*** [-2.47]**

Panel C: Calendar time four-factor model 19802000 period Value-weighted Alpha coefcient -0.0029 (-0.88) Equally weighted -0.0011 (-0.33) 19801996 period Value-weighted -0.0074 (-2.67)*** Equally weighted -0.0066 (-2.21)**

Note: The buy-and-hold abnormal return (BHAR) is calculated relative to the book-to-market matched sample. To test the signicance of the mean value of buy-and-hold abnormal returns, we employ both the cross-sectional t-statistic, and the skewness-adjusted t-statistics. The three-factor regression model of Fama and French (1993) is: Rpt - Rft = ap ? bp (Rmt - Rft) ? sp SMBt ? hp HMLt ? ept. The four-factor regression model is: Rpt - Rft = ap ? bp (Rmt - Rft) ? sp SMBt ? hp HMLt ? pp PR1YRt ? ept. Rpt is the simple return on portfolio p, Rft is the return on one-month Treasury bills, Rmt is the return on a valueweighted market index, SMBt is the difference in the returns of a portfolio of small and big stocks, HMLt is the difference in the returns of a portfolio of high book-to-market stocks and low book-to-market stocks, and PR1YRt is the difference in the returns of a portfolio of high and low prior year return stocks, and ep,t is the error term for portfolio i in month t. The statistics are reported in parentheses *** Statistical signicance at the 0.01 level; ** statistical signicance at the 0.05 level

The evidence of underperformance shown for the 19801996 period, however, does not carry over to the longer 19802000 period. The alpha coefcients remain negative, but do not approach statistical signicance (t = -0.79 and -1.38). This nding might be due to the superior stock performance of small growth rms during the last few years of the 1990s, when small rms outperformed large growth rms. During most of the 1990s, large growth rms outperformed small rms. As show in Panel C, the alpha coefcient estimated from the four-factor model also produces similar evidence of underperformance for the 19801996 period, but not for the 19802000 period. The alpha coefcient is negative and signicant at the 0.01 level (t = -2.67 and -2.21). For the 19802000 period, the alpha coefcient remains negative, but not statistically signicant (t = -0.88 and -0.33). Similar to the evidence reported in Panel B from the three-factor model, these results indicate that underperformance of private equity placements might not be robust to different sample periods.

123

238

D.-W. Chou et al.

4.3 Post-issue stock performance for DCA quartiles Table 4 contains post-issue average abnormal returns for DCA quartiles, without controlling for rm size across quartiles. Buy-and-hold abnormal returns (BHARs) relative to size and book-to-market matched rms are presented in Panel A, monthly average abnormal returns relative to the three-factor model are presented in Panel B, and monthly abnormal returns relative to the four-factor model are presented in Panel C. Panel A shows that rms in the most aggressive DCA quartile (i.e., Quartile 1) have the worst mean 3-year BHARs, with -24.50% and -21.95% for the 19802000 period and the 19801996 period, respectively. These BHARs are statistically signicant, regardless of the test statistics used. The negative BHARs for Quartile 1 are followed closely by the average 3-year BHARs of -21.59% and -20.23% for Quartile 2. These BHARs are statistically signicant, except when the skewness-adjusted t-statistic is used for the 19801996 period (t = -1.61). Results for the two more aggressive DCA quartiles provide evidence of underperformance following private placements of equity. In contrast, rms in the more conservative DCA quartiles (i.e., Quartile 3 and Quartile 4) do not show signicant experience of underperformance. Mean BHAR for these two quartiles are slightly negative with one case of being positive, but insignicant. Since rms in the two more aggressive quartiles exhibit BHAR that are negative and signicant, but rms in the two more conservative quartile do not, there is some indication that rms practicing aggressive earnings management around private placements experience worse post-offering stock performance than rms that do not. As shown in Panel B, average abnormal returns relative to the FamaFrench threefactor model show signicant underperformance only for rms in the most aggressive quartile (i.e., the quartile with the highest DCA). For the 19802000 period, the estimated alpha coefcient (i.e., average monthly abnormal return) is -0.0214, which is signicant at the 0.01 level (t = -3.43). This monthly abnormal return implies a 3-year abnormal return of -54.1%. For the 19801996 period, the alpha coefcient of -0.0174 is signicant at the 0.05 level (t = -2.53), implying a 3-year abnormal return of -46.8%. The estimated alpha coefcients shown for Quartiles 2, 3, and 4 are negative, but not signicant for all cases. A monotonic relation between DCA quartile and the estimated alpha coefcient is not evident in the results shown in Panel B. Consequently, there is not much evidence of a negative relation between DCA and post-issue stock returns. Panel C contains estimates of monthly abnormal returns measured relative to the fourfactor model for DCA quartiles. Again, evidence of underperformance is exhibited for rms in the most aggressive DCA quartile during both periods, but not for the other three quartiles in either period. Monthly abnormal returns, measured by the alpha coefcient, are negative and statistically signicant for rms in the most aggressive DCA quartile during both sample periods, but not for the other three quartiles. Again, there is not much of a pattern of abnormal returns across DCA quartiles, except for signicant underperformance shown by the most aggressive DCA quartile. Overall, results in Table 4 show some evidence of underperformance for rms that practice aggressive earnings management around an equity private placement. In the next section, we will examine whether these results are robust to controlling for rm size in size-equivalent DCA portfolios.

123

Earnings management and long-run stock performance

239

Table 4 Post-issue 3-year buy-and-hold abnormal returns and calendar-time average monthly abnormal returns relative to the three-factor and four-factor models for the DCA quartiles of 289 private placements of equity from 1980 to 2000

Sample period Quartile 1 2 3 4

Panel A: 3-year BHAR relative to size and book-to-market matched rms for DCA quartiles 19802000 Mean BHAR Cross-sectional t-stat. Skewness-adjusted t-stat. N 19801996 Mean BHAR Cross-sectional t-stat. Skewness-adjusted t-stat. N 19802000 Alpha coefcient WLS t-stat. Implied 3-year abnormal returns N 19801996 Alpha coefcient WLS t-stat. Implied 3-year abnormal returns N -24.50% (-2.92)*** [-2.37]** 72 -21.95% (-2.08)** [-1.73]* 52 -0.0214 (-3.43)*** -54.1% 72 -0.0174 (-2.53)** -46.8% 52 -21.59% (-2.68)*** [-2.11]** 73 -20.23% (-2.25)** [-1.61] 51 -0.0024 (-0.38) -8.3% 73 -0.0052 (-0.89) -17.1% 51 -7.70% (-0.41) [-0.39] 72 12.27% (0.47) [0.53] 48 -0.0081 (-1.23) -25.4% 71 -0.0067 (-0.85) -21.5% 48 8.42% (-0.67) [-0.64] 72 -6.57% (-0.49) [-0.47] 51 -0.0019 (-0.25) -6.6% 71 -0.0088 (-1.29) -27.3% 50

Panel B: Monthly abnormal returns and 3-year abnormal returns relative to three-factor model for DCA quartiles

Panel C: Monthly abnormal returns and implied 3-year abnormal returns relative to the four-factor model for DCA quartiles 19802000 Alpha coefcient WLS t-stat. Implied 3-year abnormal return N 19801996 Alpha coefcient WLS t-stat. Implied 3-year abnormal return N -0.0152 (-2.44)** -42.4% 72 -0.0136 (-1.92)* -38.9% 52 0.0037 (0.57) 14.2% 73 -0.0069 (-1.15) -22.1% 51 -0.0057 (-0.85) -18.6% 71 0.0005 (0.06) 1.8% 48 0.0025 (0.32) 9.4% 71 -0.0075 (-1.07) -23.7% 50

Note: The buy-and-hold abnormal return (BHAR) is calculated relative to the book-to-market matched sample. To test the signicance of the mean value of buy-and-hold abnormal returns, we employ both the cross-sectional t-statistic, and the skewness-adjusted t-statistics. The three-factor regression model of Fama and French (1993) is: Rpt - Rft = ap ? bp (Rmt - Rft) ? sp SMBt ? hp HMLt ? ept. The four-factor regression model is: Rpt - Rft = ap ? bp (Rmt - Rft) ? sp SMBt ? hp HMLt ? pp PR1YRt ? ept. Rpt is the simple return on portfolio p, Rft is the return on 1-month treasury bills, Rmt is the return on a value-weighted market index, SMBt is the difference in the returns of a portfolio of small and big stocks, HMLt is the difference in the returns of a portfolio of high book-to-market stocks and low book-to-market stocks, and PR1YRt is the difference in the returns of a portfolio of high and low prior year return stocks, and ep,t is the error term for portfolio i in month t. The regression coefcients reported in the table are estimated using weighted least squares for value-weighted portfolios. The implied 3-year abnormal returns are estimated as: (1 ? alpha coefcient)36 - 1 *** Statistical signicance at the 0.01 level; ** statistical signicance at the 0.05 level; * statistical signicance at the 0.10 level

4.4 Post-issue stock performance for size-equivalent DCA quartiles Table 5 contains post-issue average abnormal returns for size-equivalent DCA quartiles of 289 private placement rms. Buy-and-hold abnormal returns (BHAR) relative to size and

123

240

D.-W. Chou et al.

book-to-market matched rms are presented in Panel A, monthly average abnormal returns relative to the three-factor model of Fama and French (1993) are presented in Panel B, and monthly abnormal returns relative to the four-factor model are presented in Panel C. Results in Panel A of Table 5 show that, although a consistent pattern of abnormal returns is shown in Table 4, such a pattern is not evident after controlling for rm size. For the 19802000 period, the most aggressive DCA quartile is the only quartile that exhibits abnormal negative BHARs signicant at the .05 level (t = -1.98). Although less significant (t = -1.76), the mean abnormal return for the most conservative quartile is slightly worse, as is the mean abnormal return for the second most conservative quartile. For the 19801996 period, the greatest underperformance is not shown by the most aggressive size-equivalent DCA quartile. Furthermore, the most aggressive size-equivalent portfolio does not even exhibit underperformance that is signicant at any conventional level (t = -1.59). The second most conservative quartile is the only quartile with abnormal BHARs that are signicant at the .05 level (t = -2.55). Panel B of Table 5 contains monthly abnormal returns relative to the Fama and French (1993) three-factor model for size-equivalent DCA quartiles. Again, there is not much evidence of a monotonic relation between size-adjusted DCA quartile and post-offering performance. The only quartile exhibiting signicant negative abnormal performance over the 19802000 period is the most conservative quartile. This nding is opposite to the hypothesis that more aggressive DCA quartiles would exhibit greater underperformance following the offering. For the 19801996 period, the second most aggressive size-equivalent DCA portfolio exhibits signicant underperformance at the .10 level (t = -1.82). None of the other quartiles show signicant abnormal returns. Panel C of Table 5 contains monthly abnormal returns relative to the four-factor model. Results are very similar to those reported for the three-factor model in Panel B. Again, the only quartile exhibiting negative and signicant abnormal performance over the 19802000 period is the most conservative quartile. The only quartile exhibiting negative and signicant abnormal performance over the 19801996 period is the second most aggressive quartile. If anything, the four-factor model shows a lesser degree of underperformance for any of the quartiles. In particular, over the 19802000 period, abnormal returns for the most aggressive quartile and the second most conservative quartile are positive, although not statistically signicant. The nding of positive abnormal returns for two out of four quartiles during the 19802000 period raises the question as to whether stock returns exhibit underperformance at all following private placements over this sample period. 4.5 Regressions of post-issue 3-year stock performance To test whether long-term post-issue stock performance can be explained by DCA, we estimate a cross-sectional regression of the 3-year market-adjusted BHARs with DCA as an independent variable, and rm size and book-to-market as control variables. The results of the regression model are presented in Table 6. The coefcient for DCA is negative but not statistically signicant, regardless whether the value-weighted (t = -1.35) or equally weighted market index (t = -1.18) is used as the benchmark. We do not nd evidence of a negative relation between post-offering long-term stock performance and the magnitude of DCA, unlike results of previous research for IPOs and SEOs [e.g., Teoh et al. (1998a, b)]. Our results shown in Table 6 do not provide signicant evidence in support of a negative relation between DCA and post-issue long-term stock returns following private placements of equity after controlling for rm size and book-to-market. These results are

123

Earnings management and long-run stock performance

241

Table 5 Post-issue 3-year buy-and-hold abnormal returns and calendar-time average monthly abnormal returns relative to the three-factor and four-factor models for the size-equivalent DCA quartiles of 289 private equity placements Sample period Quartile 1 (most aggressive) 2 3 4

Panel A: 3-year BHAR relative to size and book-to-market matched rms for size-equivalent DCA quartiles 19802000 Mean BHAR Skewness-adjusted t-stat. N 19801996 Mean BHAR Skewness-adjusted t-stat. N 19802000 Alpha coefcient WLS t-stat. N 19801996 Alpha coefcient WLS t-stat. N 19802000 Alpha coefcient WLS t-stat. N 19801996 Alpha coefcient WLS t-stat. N -19.73% (-1.98)** 73 -19.65% (-1.59) 51 -0.0035 (-0.45) 73 -0.0089 (-1.36) 51 0.0040 (0.05) 73 -0.0085 (-1.25) 51 1.85% (0.10) 72 9.8% (0.44) 51 -0.0026 (-0.46) 72 -0.0105 (-1.82)* 51 -0.0015 (-0.26) 72 -0.0119 (-1.98)** 51 -22.61% (-1.76)* 71 -28.75% (-2.55)** 50 -0.0054 (-0.78) 70 -0.0065 (-0.94) 50 0.0001 (0.01) 70 -0.0007 (-0.10) 50 -21.75% (-1.76)* 72 0.40% (0.03) 50 -0.0156 (-2.52)** 72 -0.0050 (-0.71) 49 -0.0122 (-1.94)* 72 -0.0001 (-0.01) 49

Panel B: Monthly abnormal returns relative to three-factor model for size-equivalent DCA quartiles

Panel C: Monthly abnormal returns relative to the four-factor model for size-equivalent DCA quartiles

Note: The buy-and-hold abnormal return (BHAR) is calculated relative to the book-to-market matched sample. To test the signicance of the mean value of buy-and-hold abnormal returns, we employ both the cross-sectional t-statistic, and the skewness-adjusted t-statistics. The three-factor regression model of Fama and French (1993) is: Rpt - Rft = ap ? bp (Rmt - Rft) ? sp SMBt ? hp HMLt ? ept. The four-factor regression model is: Rpt - Rft = ap ? bp (Rmt - Rft) ? sp SMBt ? hp HMLt ? pp PR1YRt ? ept. Rpt is the simple return on portfolio p, Rft is the return on 1-month treasury bills, Rmt is the return on a valueweighted market index, SMBt is the difference in the returns of a portfolio of small and big stocks, HMLt is the difference in the returns of a portfolio of high book-to-market stocks and low book-to-market stocks, and PR1YRt is the difference in the returns of a portfolio of high and low prior year return stocks, and ep,t is the error term for portfolio i in month t. The regression coefcients reported in the table are estimated using weighted least squares for value-weighted portfolios. The implied 3-year abnormal returns are estimated as: (1 ? alpha coefcient)36 - 1 *** Statistical signicance at the 0.01 level; ** statistical signicance at the 0.05 level; * statistical signicance at the 0.10 level

similar to those shown in Table 5 where rm size is controlled by using size-equivalent DCA quartiles. 4.6 Monthly calendar-time regressions: the FamaMacbeth procedure To address the issue of potential problems relating to overlapping multi-year returns employed in the regressions shown in Table 6, we estimate monthly regressions of stock

123

242

D.-W. Chou et al.

Table 6 Cross-sectional regressions of 3-year post-issue buy-and-hold abnormal returns for the sample of 289 private placements of equity from 1980 to 2000 Market index Intercept Equallyweighted Valueweighted 0.1960 (0.59) DCA BK/MK Size F-Value R2 0.015 0.014

-0.5322 (-1.18) 0.1572 (1.44) -0.0489 (-0.59) 1.33

-0.0005 (-0.00) -0.6138 (-1.35) 0.1548 (1.41) -0.0020 (-0.02) 1.16

Note: The dependent variable is the 3-year buy-and-hold abnormal stock return, adjusted for benchmark stock returns. Two benchmarks are used, the CRSP equally-weighted and value-weighted indexes. Postissue stock returns are calculated for the 3-year period, beginning the month following of the issue month. The independent variables include DCA, BK/MK and SIZE. DCA is the discretionary current accruals in the issue year. BK/MK is the natural logarithm of the ratio of book value over market value of equity at the scal year of prior to the issue. SIZE is the natural logarithm of the closing price of common stock multiplied by the number of shares outstanding at the scal year end prior to the issue. The t-statistics appear in parentheses *** Statistical signicance at the 0.01 level; ** statistical signicance at the 0.05 level; * statistical signicance at the 0.10 level

returns following a procedure developed by Fama and MacBeth (1973) and also used by Teoh et al. (1998a, b). Similar to Teoh et al., an interaction variable is used to capture the incremental explanatory power for post-issue returns by immediate pre-issue DCA, relative to DCA effects for other periods. The interaction variable (DCA*Dummy) is constructed so that the dummy takes a value of one for DCA immediately preceding an issue and zero otherwise. Since we nd no signicant evidence of positive DCA around the issue year and no signicant evidence of a negative relation between DCA and 3-year stock returns in an OLS regression, we expect that signicance for this variable is unlikely. Other independent variables in the regression model are the three independent variables used in the crosssectional regression reported in Table 6. These are DCA, the book-to-market ratio, and rm size, with natural logarithms of the last two variables used in the model. We estimate three sets of monthly regressions of stock returns for the 3 years following private placements of equity; the rst set for year ?1, the second set for year ?2, and the third set for year ?3, relative to year 0 (the issue year). Each set of regressions includes about 240 monthly cross-sectional regressions of stock returns. The rst set of regressions begins in 1982 and ends in 2001; the second set of regressions begins in 1983 and ends in 2002; the third set of regressions begins in 1984 and ends in 2003. For year ?1 monthly regression, the dummy is set to one for DCA from the preceding year and zero otherwise, for year ?2 monthly regressions, the dummy is set to one for DCA from 2 years prior and zero otherwise, and for year ?3 regressions, the dummy is set to one for DCA from 3 years prior and zero otherwise. We aggregate the coefcients of monthly regressions to calculate average coefcients for each of the 3 years. The standard t-statistic is used to test signicance of the average coefcient. As shown in Table 7, the average coefcient for the DCA variable is negative for all three sets of regressions, but not statistically signicant at the conventional level. The average coefcient for the DCA variable for the third year following the issue year is negative and marginally signicant (t = -1.59). This result indicates a negative but not particularly strong relation between DCA and return in non-offering periods. The average coefcient for the DCA*Dummy variable for the second year following the issue year is negative and marginally signicant (t = -1.60). The coefcient for the

123

Earnings management and long-run stock performance

243

DCA*Dummy variable for the other 2 years, however, is positive and insignicant. A negative value for the coefcient is consistent with an increase in the relation between explanatory DCA and return during private placement periods, but a positive value is not. Overall, the results of the monthly regressions of stock returns shown in Table 7 are consistent with the results of the regressions of 3-year stock returns shown in Table 6. We conclude that our results are robust to whether multi-year regressions or calendar time monthly regressions are used. Unlike IPOs and SEOs, there is no signicant evidence of a general negative relation between DCA and post-issue stock returns for private placements of equity. 4.7 Summary of results Our examination of earnings management and its relation to long-term returns utilizes two alternative measures of DCA and three alternative measures of post-offering performance. Neither of the alternative estimates of DCA provides signicant evidence of earnings management and neither shows a signicant relation to any of three alternative measures of long-term returns after controlling for rm size. We control for rm size by using sizematched DCA quartiles and by incorporating rm size as a control variable in an OLS regression model and as a control variable in a FamaMacbeth calendar time regression model. Each of the three approaches to controlling for rm size removes any signicant relation between DCA and long-term returns. Therefore, if investor over-optimism is responsible for post-offering underperformance following private placements, we are comfortable in the belief that any investor over-optimism is not due to earnings management. The alternative estimates of post-offering returns uniformly show evidence of underperformance during the 19801996 sample period but not during the 19802000 sample period. In the later sample period there is no evidence of underperformance from abnormal returns estimated from the three factor model or the four-factor model.

Table 7 Time-series averages of monthly cross-sectional regressions of stock returns for the sample of 289 private placements of equity DCA Year ?1 Year ?2 Year ?3 Average coefcient t-statistic Average coefcient t-statistic Average coefcient t-statistic -0.0180 (-0.26) -0.0627 (-1.02) -6.5585 (-1.59) DCA*Dummy 5.5530 (0.97) -5.5702 (-1.60) 4.1799 (0.64) Size 0.0020 (0.47) 0.0027 (1.01) 0.0030 (0.89) BK/MK 0.0018 (0.77) 0.0017 (0.70) 0.0042 (1.91)*

Note: The dependent variable is monthly stock returns. DCA is the discretionary current accruals in the issue year. DCA*Dummy is an interaction variable of DCA and a dummy variable that is one when immediate pre-issue DCA is used and zero otherwise. BK/MK is the natural logarithm of the ratio of book value over market value of equity at the scal year end prior to the issue. SIZE is the natural logarithm of the closing price of common stock multiplied by the number of shares outstanding at the scal year end prior to the issue. The average coefcient is the time-series averages of each months cross-sectional coefcient. The t-statistics are reported in parentheses *** Statistical signicance at the 0.01 level; ** statistical signicance at the 0.05 level; * statistical signicance at the 0.10 level

123

244

D.-W. Chou et al.

5 Conclusions We investigate whether, like public equity issues (IPOs and SEOs), earnings management is prevalent for rms issuing equity privately and whether the earnings management explanation for poor long-run stock performance of public issues can also hold for private issues of equity. Unlike public equity issues, we nd little evidence of earnings management for rms issuing equity privately. This evidence is consistent with the view that the opportunity for earnings management in private issues might be more limited than for public issues due to the lesser degree of information asymmetry between managers and purchasers of private equity issues. Also unlike public issues of equity, we do not nd an overall signicant negative relation between the proxies for earnings management and stock performance following private placements of equity. After controlling for rm size across earnings management quartiles, in a regression model, or a FamaMacbeth calendar time regression model, the evidence of worse stock price performance for quartiles with greater magnitude of earnings management disappears. We show that controlling for rm size is a critical issue in studying the effects of private placements. Our nding of lesser evidence of underperformance during the 19802000 period, as compared to the earlier 19801996 period, could be due to structural change in the market for private placements, with the greater participation by hedge funds in this market or the development of more exotic instruments for the private placement market. It could also be due to changing market leadership after the Internet bubble period of the late 1990s. During much of the 1990s large growth rms outperformed small rms and value rms. After the bubble, small rms experienced better performance. In any event, our ndings suggest further investigation of structural changes in the market for private equity placements and effects of those structural changes on post-offering performance. Our overall ndings provide another example of the uniqueness of private equity placements. Not only does their announcement effect differ from public offerings, but the absence of earnings management also differs from the documented presence of earnings management prior to public offerings. Since earnings management does not explain the post-offering underperformance following private placements, as it does for public offerings, researchers must look to other characteristics of rms issuing equity privately in order to provide an explanation.

Acknowledgments The authors wish to thank Mike Hertzel for valuable comments on a previous version of this manuscript. Any errors remain ours. Feng-Ying Liu acknowledges support of a Davis fellowship from Rider University.

References

Barber BM, Lyon JD (1997) Firm size, book-to-market ratios, and security returns: a holdout sample of nancial rms. J Finance 52:875884. doi:10.2307/2329503 Barclay MJ, Holderness CJ, Sheehan DP (2004) Private placements and managerial entrenchment. Paper presentation, American Finance Association annual meetings, San Diego Brophy DJ, Ouimet P, Sialm C (2004) PIPE dreams?: The impact of security structure and investor composition on the stock price performance of companies issuing equity privately. Working paper, University of Michigan Carhart MM (1997) On persistence in mutual fund performance. J Finance 52(1):5782. doi:10.2307/ 2329556

123

Earnings management and long-run stock performance

245

Chou DW, Gombola MJ, Liu FY (2006) Earnings management and stock performance of reverse leveraged buyouts. J Finance Quant Anal 41(2):407438. doi:10.1017/S002210900000212X DuCharme LL, Malatesta PH, Sefcik SE (2004) Earnings management, stock issues, and shareholder lawsuits. J Finance Econ 71(1):2744. doi:10.1016/S0304-405X(03)00182-X Fama E (1998) Market efciency, long-term returns, and behavioral nance. J Finance Econ 49:283306. doi:10.1016/S0304-405X(98)00026-9 Fama E, French KR (1992) The cross-section of expected stock returns. J Finance 47:427465. doi: 10.2307/2329112 Fama E, French KR (1993) Common risk factors in the returns on stocks and bonds. J Finance Econ 33: 356. doi:10.1016/0304-405X(93)90023-5 Fama E, MacBeth J (1973) Risk, return and equilibrium: empirical tests. J Polit Econ 81:607636. doi: 10.1086/260061 Goh J, Gombola MJ, Lee HW, Liu FY (1999) Private placements of common equity and earnings expectations. Finance Rev 34(3):1932. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6288.1999.tb00460.x Hall P (1992) On the removal of skewness by transformation. J Roy Statist Soc Ser B Methodol 54:221228 Hertzel M, Smith RL (1993) Market discounts and shareholder gains for placing equity privately. J Finance 48:459485. doi:10.2307/2328908 Hertzel M, Lemmon M, Linck JS, Rees L (2002) Long-run performance following private placements of equity. J Finance 57(6):25952617. doi:10.1111/1540-6261.00507 Jo H, Kim Y (2007) Disclosure frequency and earnings management. J Finance Econ 84:561590. doi: 10.1016/j.jneco.2006.03.007 Jones JJ (1991) Earnings management during import relief investigations. J Acc Res 29(2):193228. doi: 10.2307/2491047 Kothari SP, Leone AJ, Wasley CE (2005) Performance matched discretionary accrual measures. J Acc Econ 39:163197. doi:10.1016/j.jacceco.2004.11.002 Lyon JD, Barber BM, Tsai CL (1999) Improved methodology for tests of long-run abnormal stock returns. J Finance 54(1):165201. doi:10.1111/0022-1082.00101 Mitchell ML, Stafford E (2000) Managerial decisions and long-run stock price performance. J Bus 73: 287320. doi:10.1086/209645 Mola S, Loughran T (2004) Discounting and clustering in seasoned equity offering prices. J Finance Quant Anal 39(1):123. doi:10.1017/S0022109000003860 Perry SE, Williams TH (1994) Earnings management preceding management buyout offers. J Acc Econ 18(2):157179. doi:10.1016/0165-4101(94)00362-9 Rangan S (1998) Earnings management and the performance of seasoned equity offerings. J Finance Econ 50:101122. doi:10.1016/S0304-405X(98)00033-6 Ritter J (1991) The long-run performance of initial public offerings. J Finance 46(1):327. doi: 10.2307/2328687 Teoh SH, Wong TJ (2002) Why new issues and high-accrual rms underperform: the role of analysts credulity. Rev Finance Stud 15(3):869900. doi:10.1093/rfs/15.3.869 Teoh SH, Welch I, Wong TJ (1998a) Earnings management and the long-run market performance of initial public offerings. J Finance 53(6):19351974. doi:10.1111/0022-1082.00079 Teoh SH, Welch I, Wong TJ (1998b) Earnings management and the underperformance of seasoned equity offering. J Finance Econ 50:6399. doi:10.1016/S0304-405X(98)00032-4 Wruck KH (1989) Equity ownership concentration and rm value: evidence from private equity nancing. J Finance Econ 23:318. doi:10.1016/0304-405X(89)90003-2

123

You might also like

- Does Weak Governance Cause Weak Stock Returns An Examination of Firm Operating Performance and Investors' ExpectationsDocument33 pagesDoes Weak Governance Cause Weak Stock Returns An Examination of Firm Operating Performance and Investors' ExpectationsikangNo ratings yet

- Earnings ManagementDocument32 pagesEarnings ManagementMathilda ChanNo ratings yet

- Kim Heessoo 10621377 BSC ECBDocument20 pagesKim Heessoo 10621377 BSC ECBatktaouNo ratings yet

- Milena 2012Document47 pagesMilena 2012rehan44No ratings yet

- Long-run IPO performance analysis of UK and German firmsDocument5 pagesLong-run IPO performance analysis of UK and German firmsOm PatelNo ratings yet

- The Market Disciplinary Effect of Asset Write-Off: Theory and Empirical Evidence From Goodwill ImpairmentDocument68 pagesThe Market Disciplinary Effect of Asset Write-Off: Theory and Empirical Evidence From Goodwill ImpairmentYupeng LinNo ratings yet

- Determinants of Corporate Capital Structure Under Different Debt Maturities (2011)Document8 pagesDeterminants of Corporate Capital Structure Under Different Debt Maturities (2011)Lê DiệuNo ratings yet

- Subba ReddyDocument47 pagesSubba Reddyankitjaipur0% (1)

- Yu 2011Document15 pagesYu 2011atktaouNo ratings yet

- Dividend Declaration and Stock Price Behavior: Indian EvidencesDocument11 pagesDividend Declaration and Stock Price Behavior: Indian EvidencesAKASHNo ratings yet

- How Stock Issuance Predicts Factor ReturnsDocument38 pagesHow Stock Issuance Predicts Factor Returnsresat gürNo ratings yet

- Does Dividend Policy Foretell Earnings Growth?: Draft: December 2001 Comments WelcomeDocument34 pagesDoes Dividend Policy Foretell Earnings Growth?: Draft: December 2001 Comments WelcomeSnehanshu BanerjeeNo ratings yet

- Fama 1998Document25 pagesFama 1998Rizqi NadhirohNo ratings yet

- Print 4Document32 pagesPrint 4Himanshu JainNo ratings yet

- The IPO Derby: Are There Consistent Losers and Winners On This Track?Document36 pagesThe IPO Derby: Are There Consistent Losers and Winners On This Track?phuongthao241No ratings yet

- Corporate PuzzleDocument61 pagesCorporate PuzzlesimplyankurguptaNo ratings yet

- Dynamics and Determinants of Dividend Policy in Pakistan (Evidence From Karachi Stock Exchange Non-Financial Listed Firms)Document4 pagesDynamics and Determinants of Dividend Policy in Pakistan (Evidence From Karachi Stock Exchange Non-Financial Listed Firms)Junejo MichaelNo ratings yet

- Catering Theory by Baker & WurglerDocument42 pagesCatering Theory by Baker & Wurglerarchaudhry130No ratings yet

- Report On Dividend PolicyDocument21 pagesReport On Dividend PolicyMd. Golam Mortuza78% (9)

- An international analysis of earnings, stock prices andDocument38 pagesAn international analysis of earnings, stock prices andelielo0604No ratings yet

- CampelloSaffi15 PDFDocument39 pagesCampelloSaffi15 PDFdreamjongenNo ratings yet

- Fuwei JiangDocument58 pagesFuwei JiangDr. Naveed Hussain Shah Assistant Professor Department of Management SciencesNo ratings yet

- Do Tracking Stocks Reduce Informational Asymmetries by Elder Et Al. (JFR 2005)Document18 pagesDo Tracking Stocks Reduce Informational Asymmetries by Elder Et Al. (JFR 2005)Eleanor RigbyNo ratings yet

- Do Mergers Create or Destroy Value? Evidence From Unsuccessful MergersDocument26 pagesDo Mergers Create or Destroy Value? Evidence From Unsuccessful MergersemkaysubhaNo ratings yet

- Corporate Governance and Capital Structure DynamicsDocument63 pagesCorporate Governance and Capital Structure Dynamicskrenari68No ratings yet

- Main Chapter TwoDocument10 pagesMain Chapter TwoNicholas Mensah100% (1)

- Main Chapter TwoDocument10 pagesMain Chapter TwoNicholas MensahNo ratings yet

- Liu NguyenDocument33 pagesLiu NguyenYulianita AdrimaNo ratings yet

- Control and Bank Performance: Lawrence Fogelberg and John M. GriffithDocument7 pagesControl and Bank Performance: Lawrence Fogelberg and John M. GriffithArie ToddopuliNo ratings yet

- Dampak Manajemen Laba Terhadap Alokasi Investasi Perusahaan Siti RokhaniyahDocument11 pagesDampak Manajemen Laba Terhadap Alokasi Investasi Perusahaan Siti RokhaniyahRossita SariNo ratings yet

- Is The Market Surprised by Poor Earnings Realizations Following Seasoned Equity Offerings?Document41 pagesIs The Market Surprised by Poor Earnings Realizations Following Seasoned Equity Offerings?cipsfuyNo ratings yet

- Backdate 08182009 1Document37 pagesBackdate 08182009 1Yu Hua AnNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id770805Document47 pagesSSRN Id770805mishuk77No ratings yet

- Determinants of Dividend Policy in Saudi Listed CompaniesDocument10 pagesDeterminants of Dividend Policy in Saudi Listed CompaniesChickenrock TangerangNo ratings yet

- By Suleiman, Hamisu Kargi Phd/Admin/11934/2008-2009Document26 pagesBy Suleiman, Hamisu Kargi Phd/Admin/11934/2008-2009Lareb ShaikhNo ratings yet

- 7.5.2013 The Bumpy Road To OutperformanceDocument8 pages7.5.2013 The Bumpy Road To OutperformanceTBP_Think_TankNo ratings yet

- The Relationship Between Information Asymmetry and Dividend PolicyPapDocument56 pagesThe Relationship Between Information Asymmetry and Dividend PolicyPapRaj KumarNo ratings yet

- Stock SplitDocument36 pagesStock SplitSivakarthik SubramanianNo ratings yet

- Capital Structure, Cost of Debt and Dividend Payout of Firms in New York and Shanghai Stock ExchangesDocument9 pagesCapital Structure, Cost of Debt and Dividend Payout of Firms in New York and Shanghai Stock ExchangesDevikaNo ratings yet

- Detect Earnings Manipulation with Discretionary Accrual ModelsDocument34 pagesDetect Earnings Manipulation with Discretionary Accrual ModelsAlmizan AbadiNo ratings yet

- Can Mutual Fund Managers Pick Stocks? Evidence From Their Trades Prior To Earnings AnnouncementsDocument34 pagesCan Mutual Fund Managers Pick Stocks? Evidence From Their Trades Prior To Earnings AnnouncementsHendri AnjayantoNo ratings yet

- Sje 22 2 263Document26 pagesSje 22 2 263Enerel Otgonbayar (Eny)No ratings yet

- IraniOesch AnalystCoverageEarningsManagementDocument48 pagesIraniOesch AnalystCoverageEarningsManagementshadoNo ratings yet

- Do Dividends Forecast Future EarningsDocument57 pagesDo Dividends Forecast Future EarningsatktaouNo ratings yet

- Dividend Policy of Indian Corporate FirmsDocument19 pagesDividend Policy of Indian Corporate FirmsRoads Sub Division-I,PuriNo ratings yet

- Dividend PolicyDocument8 pagesDividend PolicyHarsh SethiaNo ratings yet

- Review of LiteratureDocument9 pagesReview of Literaturesonabeta07No ratings yet

- Testing The Pecking Order Theory: The Impact of Financing Surpluses and Large Financing DeficitsDocument40 pagesTesting The Pecking Order Theory: The Impact of Financing Surpluses and Large Financing DeficitsatktaouNo ratings yet

- Earnings Management and The Post-Earnings Announcement DriftDocument54 pagesEarnings Management and The Post-Earnings Announcement DriftIosiasNo ratings yet

- Corporate Focus Drives Stock ReturnsDocument21 pagesCorporate Focus Drives Stock ReturnsCẩm Anh ĐỗNo ratings yet

- Stock Performance or Entrenchment? The Effects of Mergers and Acquisitions On CEO CompensationDocument55 pagesStock Performance or Entrenchment? The Effects of Mergers and Acquisitions On CEO CompensationLoren SteffyNo ratings yet

- Yale Spring Load AccountingDocument44 pagesYale Spring Load AccountingMessina04No ratings yet

- Financial Performance Impact on Stock PricesDocument14 pagesFinancial Performance Impact on Stock PricesMuhammad Yasir YaqoobNo ratings yet

- Thesis On Determinants of Capital StructureDocument4 pagesThesis On Determinants of Capital Structuredwbeqxpb100% (2)

- Investor Behavior and The Timing of Secondary Equity OfferingsDocument43 pagesInvestor Behavior and The Timing of Secondary Equity Offeringsteeravac vacNo ratings yet

- Agency Costs and The Dividend DecisionDocument17 pagesAgency Costs and The Dividend DecisionhhhhhhhNo ratings yet

- Does Corporate Performance Determine Capital Structure and Dividend Policy?Document57 pagesDoes Corporate Performance Determine Capital Structure and Dividend Policy?DevikaNo ratings yet