Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Santa Claus: Glyndel and The Cave of Souls

Uploaded by

Mike WolfkielOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Santa Claus: Glyndel and The Cave of Souls

Uploaded by

Mike WolfkielCopyright:

Available Formats

2011

Dear Patrick, Erin, Nick, Elves everywhere, and any interested, This year I write of things I dont begin to understand. Your always friend,

Santa Claus,

who wishes you the Merriest of Christmases and that you enjoy

Glyndel and the Cave of Souls

This year I want to tell you about a place. It is a cave located in the hills just to the east of our village here at the North Pole. The elves stay away from it. They call it The Cave of Souls. It speaks to them of things theyd rather not know about. But it is truly an extraordinary place. I like to work there on the naughty or nice list. Within the cave, its walls are coated with ice and crystals, and these catch any light, reflecting and splitting it, setting the cave aglow with all the reds, blues, greens and yellows of the rainbow. And a breeze always circulates, sometimes warm and at others cold, sometimes loud and wailing and at others a soothing silence or playful whistling. The elves say spirits live in those winds, and that the spirits speak if you know how to listen. It is filled with corners, crevices and little shelves of stone, and were you to enter the cave you might 182

even find some odd object upon one of the ledges. It might be a trinket, a beloved toy, or even a comb, blanket, book, or picture. But then again you might not find anything, the cave is unpredictable in what it reveals and to whom it reveals. To me it is a sacred place, and, in truth its story has no beginning except something so deep within each of us, that if you tried to speak of it, the words would crush with their weight what they wanted to express. This is a story about two of its shelves, and about the curious connection between Minah Strangway and Glyndel Hebbert.

In the human world of San Francisco sits a building that you would think would be one of the happiest places on earth, because their work is to design and create games, games that people play on their computers, and televisions, and even on their telephones. Mike Strangway sits in that building in front of his computer examining lines of computer code, and if you asked, he couldnt tell you why. Oh, he could tell you that he was sniffing out some code sequences that caused images to appear reversed, or he was trying to figure out why the game would shut down just when the ball on the screen entered the goal. He could tell you about the properties of various computer chips, and the processes by which they were made, and he was even learning about various marketing strategies by which his companys products were sold. But he couldnt tell you why any of it mattered. Worst of all, he wasnt even aware that hed lost touch with this fundamental motive.

183

Personally, I think that even in humans, fundamental motives are best when elvish. Which shouldnt have been a problem for Mike, for he grew up at the pole, as elvish as any child. He was called Minah then, and in fact when Glyndel was very young, he played with her. Looking back some elves say that was the cause. They infected each other, they say. Infected with what, I heard Groldin Dinsmore once ask as he overheard some elvish girls talking about Glyndel and Minah. The elves tittered, and finally squeezed out their answer, Human disease. Then they giggled and scattered. Elfy nonsense, growled Groldin stomping away and mumbling, Now where is that leaky pipe? But it is no disease. And when they did meet Glyndel was so young it stretches the imagination to believe Minah had much effect on her. Heres what I have heard about that encounter. Glyndel was only an elf toddler, breaking teeth and learning to speak. Minah was already apprenticed to the clockmaker Dockery. Humans would call him a teenager, and Dockery had sent him to the Hebbert cottage, because Glyndels father worked in the inks and paints shop. I guess Dockery needed some special inks for a watchface. When Minah arrived and asked for Master Hebbert, Glyndels mother was a bit harried. Without thinking she deposited the toddler she had been holding in Minahs arms and went in search of her husband. Now it is true that Minah had not spent much time with younger elves, and no one is quite certain exactly what happened. But Glyndels mother, Donata, says that when she returned to tell Minah that her husband must have gone off to the shop where he belonged, she found the two playing a little

184

game. Minah was on the floor crawling behind the furniture and little Glyndel was searching for him. Minah peeked out from behind the sofa, said, Could I be over here? Boo! then as Glyndel laughed and ran for him he scurried away behind the arm chair. Finally the she stumbled on to him screaming, It, it it! Youre it. Minah caught her up in a tickle hug, and said, Could I be that, instead? (You see, in those days, he tended to speak in questions.) What, asked the confused little girl. Yes, replied Minah. Just what am I? Youre it-that, that what, she said. Play gain? And that of course is when Donata broke in, for parents always interrupt play at the perfect worst possible moment. So, no infection, just play, ordinary elvishness. At that point Minah was still more elvish. But, as will happen, as does happen everywhere, things changed. Minah grew, matured. It is just the way of things, nature. Minah was by nature human, Mike more than Minah, and growing up.

Glyndel Hebbert was a spry and bright elf girl just bursting with energy. Her earliest years at the pole were filled with tag and chase, and games of will o the wisp. More than anything she loved to snowglide. Elves you see are so very light they can walk on the snow, and they have developed these special shoes made of stiff leather treated to slide on the snow, gliders they call them. So they can glide across any but the

185

powderiest or the meltingest of snows. In the yearly snow games, the gliding events are the most popularthe long leap, the sprints, slaloms, mountain runs, and trick events are all quite beloved. And Glyndel glided like no other. She spun and flipped, dancing from one foot to another, speeding faster than any elf had ever seen. She was a joy to behold, streaking along, her eyes wide with excitement, trying new tricks, or gracefully slipping effortlessly across cottage rooftops and onto rock ledges or tree branches, any place where snow collected. For Glyndel the village and its hills and trees were all a marvelous playground, a kind of canvas on which she produced an art as beautiful as any I have ever seen. Now you know that the elves love the Pole and our life here. And you know the elves are long lived, and have few children. And as these children mature they apprentice themselves to adult elf workers. In this way they usually find the shops and jobs that fill their hearts with merriment, their lives with purpose, and the world with toys. But not always. Sometimes an elf does not find a place or purpose here. And such was the case with Glyndel. She worked for a while in trinkets. She tried the woodshop. In sports, she even developed a special shoe, a gliding shoe whose sole pinched to a ridge. With them, she glided even faster, made more daring jumps, and spins, and learned to love the snow and the biting air on her cheeks even more than ever. For a while the elves were very excited. Special shoes were designed for all of the gliding events. Then they realized that these shoes were of no interest to humans who could only sink and slop in the snow. And weeks of time and work had been used and no toys or gifts came of it. So from sports, she went to the games shop. But soon the elves and she realized she had no special aptitude for it. And soon there was only one place left, the grims.

186

Now it had been years since Minah had left the pole and become Mike, and years in those cities, paying rents, sitting at those desks, and just breathing in that air in that building does strange things to a person. Mike had been banging away at that computer for a long time. He was however genuinely talented. He could breathe life into things on a computer that he could never draw or write about. I am sure he entertained and involved more children in play as an adult than he ever would have had he remained an elf at the Pole. Mikes last project was a complete triumph. It was called Donkey Kong and across Europe and the Americas these odd machines appeared in coffee shops, bus stations, and even grocery stores. Children would line up to put their quarters in and become the intrepid, indefatigable Mario, trying to out-leap barrels, outwit the ape, and rescue the girl. It was afterward that things changed. Everyone in the company had ideas for Mario, and hundreds began writing and designing games. Mike of course tended to each and every idea, and each and every line of computer code. He was overwhelmed. Perhaps it was also the awards, and the money, such things tend to corrode elvish sense. Donkey Kong was now two years old, and there was a lot of pressure. Everyone wondered what Mike would come up with next. And it was at this time, filled with pressure, and unaware that he had lost touch with his sense of play, that he met Cassandra Desanto.

187

When Glyndel was younger the other elf children admired her just as much as they did any elf child. Popularity, as a concept, is of course most unelvish, but as the normal attraction and affection elves feel for one another, it does have some meaning. When she was young Glyndels love of gliding infected those around her, teased them into its play, as pure and delightful as any play they knew. But elves are by nature curious, and their minds skip around. Twenty minutes of gliding usually guarantees that elvish minds will turn to hot chocolate, knitting scarves, or reading by a cozy fire. And when she was very young, Glyndel was no different. She would gladly tromp into some familys cottage with all the other elves, toss off her gliders, and dash into the kitchen all rosy cheeked and out of breath. But as she got older, something began to happen, nothing dramatic, but something definitely odd. When her friends tired at gliding, she tried to urge them on. Just once more around the village, shed say, or, lets see who can glide the highest branch of those pines. Now some of this is very normal and elvish. It is the usual bustle and jostling of elvish children, clamoring to do one thing or another. So it took time, but eventually they started catching on. Glyndel always seemed to want to glide and never anything else. Sometimes after gliding, all the little elves would jumble into some family cottage, and theyd gulp their hot chocolate and look out the window. And they would see Glyndel still gliding. Gliding along quite marvelously, but by herself. Playing alone. Elves are interesting creatures. As adults much of the work they do is alone in the sense that they do it by themselves. But if you suggested this to them, they would

188

laugh and point at all the others in the room. And of course some of the toys are worked on by many elves, but almost always one at a time. To the elves however, since they are in a room together, it is a group activity. Indeed, ask any grim, if you put one elf in a room, no matter how stimulating the environment, after an hour all youre going to have is no toys and one cranky, sullen elf. To an elf, playing alone, are simply two words that do not go together. Play is plural. Alone is something else, something different, something not elvish. But then there was Glyndel. There was, of course, no decision; no conscious thought, or talk about the issue; but more and more the other elf children shied away from Glyndel.

Cassandra Desanto called Mike. She consulted for a company called Nintendo, and they were interested in some kind of cooperative merger with Mikes company, and could they meet to talk about it. Light business lunch? Not available? Dinner then, and No it wouldnt take long. To Mike Strangway this Cassandra Desanto was just one more in the endless litany of people, tasks, and chores that seemed to fill his days. He vaguely remembered the company president telling him about a possible deal with Nintendo, and that they wanted to make a good impression, but there were coding problems on Mario World that commanded his attention. So when Cassandra called he agreed to the meeting, dinner the following Friday.

189

Even as adults, you would be amazed at how elves work. Each elf is usually working on several toys and projects at once. They carefully tap in a peg on this one, and then jump to another that needs painting, and before that is done, they are carving at a block of wood to start something new. You see, for them, it is still play. Most barely notice when they have finished a toy, for other projects fill their minds. This would all be terribly chaotic and Christmas impossible if it werent for the special group, the grims. The grims are the elves that constantly check on the work of the others. They collect finished toys, keep track of what gifts go to which children. They manage production. If they see a shortage coming in games for example, they dont say anything, they just place more colored papers and inks in the shop, maybe some intriguingly costumed dolls that suggest plot lines, put a picture or two on the walls that will stimulate the elves minds in the right direction. Then, voila. In a few weeks there is a surplus of games. They are called grims by the others because their specialty is an odd avoidance of play. At least thats what the other elves think. I think that their play is simply at another level. They take delight in their various stratagems for inspiring elvish work. Balls, for example, take a lot of creativity. Each year we need thousands of footballs, basketballs, and baseballs. No elf could ever sit down and make ten identical baseballs for example, much less one hundred, or the thousands needed. So the grims are forever inventing new ways to inspire the elves to make thema poster of a boy dreaming of hitting a home run, or they put up a clock with each number a different kind of ball, except the number nine is missing and

190

there are no baseballs on the clock. A week later a dozen elves have all produced nine perfect baseballs. You see, it is marvelous play for the grims. Now when a young elf has apprenticed him or, in Glyndels case, her self to all of the shops, and nothing seems to take, they begin thinking she might become a grim. So Glindel was apprenticed to Leitsprig. Leitsprig is a fastidious little elf who has a better sense of the operation, all its parts, from stable to shops, from lists to preparing the sleigh, he knew it all far better than I ever had. He knew which shops worked on what, and for whom. He coordinated the wrapping and bag stuffers. Getting the right packages in the bag for each house relies on a miracle of logistics, and at the Pole, that miracle is called Letsprig.

At around noon, on just that following Friday the phone in his office rang. Hello, this is Mike Strangway, he said in a way seemed to suggest he had no time for phone calls. Mr. Strangwaycan I call you Mike?Well, I made it. I thought you could show me the town. Mike was clueless. Uh, hello. Who is this? This? This is me. Surely you remember. Cassandra Desanto. And I thought I had felt a bluish hazel aura around our first conversation. It was so interesting that I was sure you would

191

Ms. Desanta, said Mike flipping through his Outlook program. Oh yes, dinner this evening. Our appointment is not until 7:30. Excuse me, she said. Desanto, de-san-TOE. Oh never mind, just call me Cassie. Can I call you Mike? Or do you prefer Michael? Mick, perhaps? Yes, you called me. I mean, Mike is fine, but Im not sure I know, its a glorious day, and Ive never been to San Francisco before. Where shall we go first? The Golden Gate bridge? Embarcadero? Ive heard Sausalito is interesting. Well, its only ten after twelve Which gives us, what, five or six hours of sunlight. You must suffocate in that office building. Oh, here comes my luggage, Ive got to go. Im at Uniteds baggage claim, and youll know its me, when you see a red overcoat, and a purple parasol. And the conversation was over.

It was not very long before Leitsprig met with me to review the progress of his young charge, Glyndel Hebbert. As I suspected, she was completely wrong for accounts, he said. Accountant elves track and tally toy production and check it against the lists and needs. They hold numbers in their heads better than any calculators, they are always checking production and telling the shop stewards what was needed.

192

She became enamored with all the snow centered gifts, skis, boards, goggles, gloves. It was all she could talk about. We now have so many snow shoes, and skis we wont need to make any for, let me see three years. All right, I said. We knew that was unlikely. What about the stables? I thought shed appreciate being outdoors, the air and the animals. Leitsprig tapped his pencil against my desk, and tsked. It was a thought, he said. But Im afraid well need a full backup team of reindeer this year. Why? It seems they didnt get the proper rest. Im told that a certain apprentice was, shall we say, over-enthusiastic. Instead of just stretching their legs, on daily walks, Glindel was racing with them. Oh, it was fun for her, she just couldnt understand the trainers schedules and the whole concept of rest and preparation for the Christmas eve marathon. I see. Shop Steward is, of course, too much responsibility for any apprenticing elf, so she spent a fortnight assisting Frobisher in printing and painting. She supposedly had a few decent ideas for enticing the elves. Making Christmas cards, I believe. But she couldnt stop herself from explaining the posters and arrangements of papers and materials. And no elf cares to be manipulated, they flip oppositional quickly. Frobisher has had to be cat and clever with reverse psychology since she left the shop. Well, did she fit in anywhere? Leitsprig just shook his head. Then he finally spoke. Lord Santa, there is something else. Perhaps youve noticed he paused.

193

Noticed what Leitsprig? Her height, Santa. Frobisher put me on to it. You know he is the tallest and thinnest elf at the pole. And he has an exacting eye. Late in Glindels second week, he mentioned that she seemed to be in, I believe its called a growth spurt. Half an inch in only ten days. This was a sign, a definite signal. Stretched and thin is not an elvish trait. Minah had been that way, and so had most of the elves who left the pole, passed over. There are also other developments. She is, well, becoming shall we say, quite female. I see. Theres no mistake then. No. Her elvish is slipping away. If it werent for the gliding shed probably have left already.

Mike didnt know what to think, or even where to start. Should call a limo service to pick her up? And why would she have luggage, if they were only meeting for dinner. He didnt know she was flying. And, wait a minute, how dare she just assume that he could jettison his afternoon to entertain her!

194

I dreaded the inevitable meeting with Glyndel. Such meetings are really quite rare. Most elves who leave, understand quite well what is going on. Some even enjoy their last weeks or days more than any of their previous time at the pole. Like summer sundowns, goodbyes can inspire truly wonderful play. But every once in a while, the child is taken by surprise. Leaving, she cried. You mean one of those, those, what are they called? A ceremony, I said. There hasnt been one since Ive been alive, she sniped. I thought they were a myth, an old elves tale. No, I said, trying to keep my voice calm. We simply havent needed one. Well, I dont need one, she said, glaring at me. Glyndel, you must see I see that theyre jealous, she said. Tears pooled in her eyes. They wish they could glide like me. They see what fun I have. I held my tongue, thinking that soon even she wouldnt glide like her. You will continue getting heavier, I explained. Its just the food, she said. Now the tears escaped down her cheeks. Ill eat less. Please dont make me go, Santa. She looked at me, her eyes begging. But I had no comfort to offer. Then she cried, simply let it flow. And then in gasping breaths, whined, I mean, is everybody here allergic to salad. I smiled, even chuckled, hoping that she was trying to be funny. There will be other changes. Your mother will explain. It would simply not be possible for you to continue living here.

195

And she cried, some more. When? she sniffled. Weeksend, I said. At the Cave of Souls, with the rising sun.

Thirty minutes later Mike Strangways car lurched its way down the 101. His mind busily plotted stratagems. He sought a way out, any plausible reason, any excuse he could use to drop this Cassandra de-san-TOE at her hotel, and catch up to her later, as planned, for their dinner. He knew now what she was like. He would be prepared. She spoke quickly, took control of the conversation, that was how she worked. He would have to make his point quickly and decisively. No discussion, no parasols and auras, just a firm decisive declaration of how things would be. When he arrived at United he had no trouble spotting her. Here it was early fall, a sunny California day, and there she was on the lower level, in a winter-weight red coat, wearing sunglasses, and holding a purple umbrella over her head. Just pop the trunk, she said, as he pulled up to the curb. Hed meant to get out and open the door for her at least, but then there was hardly a moment between the heavy thunk of her suitcase, the passenger door swinging open, and the rather elegant maneuver in which she simultaneously folded the umbrella and slid into the seat next to him. Once settled, she turned to him, and carefully removed her sunglasses. Her hair was brunette and her eyes a dark liquid brown, actually somewhat attractive. He was about to launch into his reasons for skipping the afternoon, when she

196

flipped up her palm, in the universal stop gesture. She looked at him. No, she studied him, then slowed her breathing, and finally extended her hand. I am Cassandra Desanto, and you never answered my question. Mike, said his mouth, while his mind was cursing himself for a fool as he realized she had done it again.

I woke the next morning and looked out my window. Glyndel was gliding around the village. At first it seemed as it always had, beautiful and inspiring. But as I looked more closely, my heart ached. Where before her gliding seemed effortless, it was now strained. I could see the bunching and pushing, a muscularity to what had once appeared as smooth, sinuous and swift as a winter breeze. It was already more work than play. Then she fell. Not a bad fall, and falls in gliding happen all the time, but there seemed little reason for this one. She had not been attempting a trick, leaping from tree to a rooftop. I thought for a moment a small stone or pine cone had snagged her. Indeed, she pulled herself up and stepped back to examine her tracksand then I knew. She was now making tracks. The heaviness. The heaviness is an odd thing. You see, to the elves her appearance seemed ever more stretched and thin. She looked less and less substantial, but all the time her body was taking on weight, leaning into the world around her in a new way. I watched Glyndel often in the days that followed our meeting. I watched her suffer what she could not control, and I watched her, furious effort to fight it off. For a

197

while I thought she was determined to spend every last minute of her elvish time on the snow. But then, the afternoon before the ceremony, her gliding had become so sluggish, that she let herself fall, pulled up her knees, hugged herself tightly. Her crying was so soft, you could barely see the trembling of her shoulders. As I understand it, that evening she visited many of the elves. Frobisher and Leitsprig, Groldin of course, but mostly the young elves she had grown with. Even though the friendships had strained in recent years, she visited each elf and their families. I am told she thanked them all and even asked a few if they would attend the ceremony.

By three that afternoon Mike Strangway had seen more of San Francisco than he had in the whole ten years hed lived there. He had heard things about her cats, her plants and her theories concerning the intersection of herbology and human auras. He was sure his dentist would be rich and busy because hed ground his teeth so hard, one had cracked. The strangest part of all of this, was that he had actually done most of the talking. So where did you live before San Francisco? How did you get interested in computers? Do you see your parents often? She was all questions. And no matter how clipped his answers, she would always follow up. So how is the weather in Vermont?

198

Didnt you find engineering fascinating? How could you prefer the virtual world, to the real one? When your father died, how did your mother handle it? The afternoon stood no chance against her, she was the Titanic of time, unexpected icebergs and then miles underwater never to be seen again. Mike couldnt remember when hed even thought much less talked so much about himself. She was, he recognized, truly a whirlwind of enthusiasm. Theyd spent an hour at Pier 39, trying to find out how they could feed the harbor sealsfeed the seals, for chrissake! And now they were on their way to Embarcadero, Belden Taverna, for dinner, and they had not yet said a single word about business, the merger. At this rate, this light business meeting would last a week.

We call it a ceremony, but, in truth, there is not much of a ritual. The elves do not celebrate such things. Im sure Glyndels invitations made for many uncomfortable conversations and decisions. The last time an elf passed over, other than Minah, it was a boyAndrion was his name. No one attended. He was as sturdy and courageous an elf as ever Id known; and he and I walked out of the village in the pre-dawn blackness, and made our way alone to the Cave of Souls. We talked about his future, where he might go, what he might become; and we recalled the various episodes, events and memories of his time with us. We laughed and cried, and then, as the sun rose, and its rays transformed the caves darkness, we hugged, and in that embrace he simply slipped away. Of course,

199

he left his traces on the little ledge that would be his from then on, a place safe, bathed in its own light, that only he could reach. I was not as sure that Glyndel was as accepting as Andrion of the inevitable transformation.

In the restaurant, they were shown the view of the bay, seated, the menus proffered, the water poured, the lemon slices encouraged, and then her eyes softened and her voice dropped. Look, I have to ask. All afternoon Ive had a great time, but these red flashes in your aura. I know I can come on a little strong, but what is it? Whats bothering you? Whats bothering me, Mike began, and he could feel the volcano about to blow. Where should I start He caught himself. Her eyes were so round, so, so vulnerable and concerned, as if she really wanted to know. --lets just talk about the merger, okay? Thats what were here for, anyway. Thats what matters. Do you have any figures? Projections. The offer? I could run down our earnings for the past three quarters. What? What is it? She struggled to restrain a smile, maybe even a chuckle. Offer? Projections? Im sorry, I must have given the wrong impression. I dont work for Nintendo, I have no idea what their financial position is. Im, well, I am a consultant. Nintendo has hired me for advice on whether to even pursue Atari.

200

What? Youre not going to buy us out? Me? Lord, no. Now Nintendo might make an offer. At least after they get my report on the potential consanguinity. Rage and confusion battled in his brows. Consanguinity, he said. The um, well, whether the fit feels right. The waiter appeared. Give us a minute, snapped Mike, and he man started to shuffle back. Oh, Im ready, said Cassandra, The Lobster Diavolo looks Mike reached out and held her wrist. I am not ready. Please, give us a minute. Wow! Major red flash in your aura. Oh yeah, seethed Mike. Consanguinity? Whether it feels right? What is this? Cassandra left her wrists in his clenched hands. She paused, and then said, Could it be dinner? Is this some kind of a joke? Has the entire afternoon been a waste of time? She thought. Hold on. I love this game. Um. Okay, here you go. Why? Wheres your patience, your sense of adventure?

After supper of the night before the ceremony, there was a knock at my door. Beggin your leave, Lord Santa, said Groldin Dinsmore, but shes gone. What? Groldin come in, I said. What are you talking about? Who is gone?

201

You know, Santa, the Glyndel glider girl. Awful thin of late. Dont think she can make it far on her own. He paused. Course, the roofs wont need as much upkeep, now. Still, she was a pretty thing. I was up from my chair and past him before he finished talking. At the Hebberts cottage, Donata and Splaygel huddled together, looked up at me, and then held out a note. She left some time ago, said Splaygel. Shes a good girl, said Donata. I took the note and read:

Mom, Dad, Santa, and Concerned Elves, Do not wait for me. I will be at the Cave at sunrise and hope to see you all there. Thank you for all the snow and play and times of tears and laughter. Love Glyndel

Perhaps we should go search for her, said Splaygel. I mean anything could happen out there. Does she even know where the Souls Cave is? Lately she has seemed so thin, so, so worried, said Donata. What should we do, Santa? I really wasnt sure what to say. The elves are usually so self-sufficient, I have never been comfortable in these situations where they want my advice. Im not sure, I 202

stammered. It really is too dark to search for her. Then I met their eyes and said, Donata, Splaygel, she says she will be there. I think the situation calls for a little faith.

Mike Strangway forced himself to let go of Cassandras wrists. It was the greatest effort of will he could rememberbut, No, it was not acceptable to break this womans arm. At least not in a restaurant, not in public. Explosions, he knew, must be flashing through his aura, and they scared even him.

So in the pre-dawn darkness I lead about twenty very nervous elves, all carrying lanterns and candles that only made it feel darker, out of the village, up the eastern slopes, into the hills, toward the Cave of Souls. For their part, the elves had no idea what to expect, and I was unsure myself. So along the way I hummed a carol, and they began to sing softly, Holy Night, The Little Drummer Boy, and even O Come All ye Faithful. I dont know if it eased any fears, but it was the only thread of comfort I could find. Then, as we worked up the hills and neared the cave, I hoped to see a light, a campfire, anything. But no. We climbed the last yards up the hill, and the only light was the emerging along the eastern horizon. Lets go in, I said.

203

As I said, the Cave is a special and even sacred space, but it is not a very comfortable or even safe space. It has its dangers. Some crevices open into crevasses, there are some jagged rocks, and the footing can be awkward and slippery with the ice. So we held hands, squinted at the darkness, felt with our feet, and inched our way in. Once inside we held hands in a loose circle, and in the darkness felt, felt for something, for Glyndel, for any presence. And in return we felt the air. A thin, slight breeze swirled and whistled, rising and dipping along an eerie scale. Is that Glyndel, said Donata. She called out GLLYNDELLLL! GLYN, GLYN, GLYN, DEL, DEL, DEL As the echoing sound died we could see outside where the eastern sky gathered its light, and then the air stirred, swirled, in drafts, warm then cold, slapping our cheeks, bringing tears to our eyes. It was that precise moment, in that bleary, tear filled vision, that the first rays leaked over the horizon, and sprinted toward the cave. And as that ray of light sped forward, the pitch of the airs whistling rose and rose. Then, all of a sudden, the air shifted, sucked out of the cave in a deep whoosh. And the light streaked in to fill the cave and exploded into a million colors that shimmered and glowed and streaked together. My God, those colors, they sang! A glorious crescendo of lights, swirling At the crest of the swirling something leaped, and swooped, and danced along the rocks, and I wondered if a shooting star had exploded into our cave. But no, the light slowed, stilled some, and I could see that at its crest was Glyndel, in her shoes gliding as never an elf or star or breeze has ever danced and spun before. In and out of our circle, under our arms. At first the elves cried out, but their keening soon softened into oohs and

204

aahs as Glyndels spins and leaps careened from wall to wall, ceiling to floor, and playing on ledges, she moved to a rhythm as enchanting as it was daring. We gasped, we thrilled, we even laughed as she burbled along a wall, skipping from one foot to another. Then she slowed to a more mellow glide and slipped into and between us, grazing our cheeks with fingers of feathery light. And after each elf had been lighted upon, touched with her breeze she spoke, her words rushing past our ears and around the cave I HAaaVE NO WOOooOORDS I SHaLL MIIIiiisSS YOUU I think these words were to be her farewell. Indeed, as she spoke them, even as her speed increased, her light, her incandescence faded, thinned and stretched. Then, at the penultimate moment, when one expected her soap bubbles delicate pop, she pulled to an abrupt halt upon a low ledge. Her body gathered solidity, and all her speed seemed to pour down her arm, which stretched deep into a crevice. Whats this, she said. And her slender white arm seemed to pour down into the rock. Then there was a scratching, and tug, and Glyndels elastic body pulled back its arm. Oh, she said as something round and shiny in her hand snapped up from the crevice. Its that. Hello Minah. All of the elastic energy that had poured down, now snapped back up her arm, into her shoulder, and sent her body, thinning and glowing with light into one last, long glide. It gathered speed, and found a spiraling path around the caves walls, climbing higher, and wispier, and higher, end then

205

Entranced, spellbound the whole time, the elves and I had only looked, slackjawed and amazed. But when Glyndels glow disappeared into the crystals of the upper cave, the shrill whistling ceased, and a light metallic ringing caught my attention. As one we moved to the lower ledge where Glyndel had paused only a moment ago. There, on that ledge, just settling was a brass pocketwatch. A gift I recognized that Carlton Dockery had long ago given to Minah Strangway. It must have fallen somehow, forgotten into a deep crevice. Look! Donata Hebbert pointed, her eyes wide. Do you see? Up there, that little shelf. I squinted, and indeed saw. High along the cave wall, on its own shelf, looking like they had a life of their own were Glyndels leather gliders, settled securely on their own ledge, safe and bathed in their own light, a place that only she could reach.

Insanely, Mike Strangway thought Cassandras aura was now flashing something. Could it be Lobster Diavolo, she asked. What are you going to have? Mike leaned back, looked again at her warm smile, and laughing eyes. Come on, she said. Its your turn. Wait, wait. I mean, Isnt it your turn? Mike turned, looked out the window. The oranges and pinks of the California sunset twinkled across the bay, and something inside him seemed to shift, to settle. A weight, a kind of shadow slipped from his shoulders.

206

He waited a full minute, before cocking his head back in her direction. Shrimp Diavolo, I mean, Wouldnt shrimp Diavolo be perfect? Then he reached forward, and with his right finger, gently tapped her wrist. Youre it. If possible, Cassandras eyes sprung even wider. Wow! Major aura shift. Shrimp Diavolo for you. Without thinking she pulled his hand to hers. And without thinking, he let her take his hand. You know, she said, I always wondered about it. Why doesnt anyone ever say Youre that, or what? Is it weird that I wonder about this stuff?

And that is how a little elvishness reanimated Mike Strangway. And that is the story of the odd connection between Glyndel Hebbertwho is now a ski instructor in Colorado, named Gloriaand Minah Strangwaywho is now married and, with his wife Cassie, are now expecting their first child. It is not, of course, the full story of the Cave of Souls, which, like I said earlier, begins sometime before words, and stretches out well beyond them. The Cave is a mystery to me, a continual source of wonder. Does the cave somehow hold the two worlds, human and elvish, together, in touch, in whatever harmony they can achieve; or does it keep them apart, separated so they each may work according to its own rules and logic? I have also often tried to imagine the other side of Glyndels ceremony in the Cave of Souls. Other crossings, Andrions for example, I imagine to be a gradual settling in to the human world. For them I imagine the moment where elf dissolves and human

207

emerges as too delicate and feathery to identify with any precision. But Glyndels crossing, what would that be? I cannot imagine, but wouldnt it be glorious to behold?

THE END

208

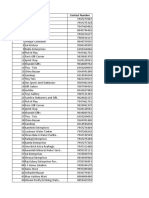

You might also like

- The Ellie McDoodle Diaries 2: Have Pen, Will TravelFrom EverandThe Ellie McDoodle Diaries 2: Have Pen, Will TravelRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (38)

- Term 2 - Mystic MilesDocument120 pagesTerm 2 - Mystic MilesProplayerNo ratings yet

- Peter Wendy ScriptDocument57 pagesPeter Wendy ScriptgregperniconeNo ratings yet

- The Burning ForestDocument7 pagesThe Burning Forestmatthewwu2003No ratings yet

- Book StoriesDocument5 pagesBook StoriesamutthaNo ratings yet

- Dapne and Velma: The Vanishing Girl ExcerptDocument32 pagesDapne and Velma: The Vanishing Girl ExcerptI Read YA100% (1)

- Stink and The Hairy Scary Spider Chapter SamplerDocument32 pagesStink and The Hairy Scary Spider Chapter SamplerCandlewick Press75% (4)

- Guys Read: Artemis Begins: A Short Story from Guys Read: Funny BusinessFrom EverandGuys Read: Artemis Begins: A Short Story from Guys Read: Funny BusinessRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (14)

- POLS272 Practice Problems 6Document6 pagesPOLS272 Practice Problems 6althaf alfadliNo ratings yet

- GEO129 Lab 10Document5 pagesGEO129 Lab 10suhardin laodeNo ratings yet

- Thaecian Isles FotBDocument81 pagesThaecian Isles FotBBurpysNo ratings yet

- Animal Diversity NOTE - 111104Document5 pagesAnimal Diversity NOTE - 111104Mohammed KasimNo ratings yet

- Animal Farm Comprehension QuestionsDocument4 pagesAnimal Farm Comprehension QuestionsJyoti JainNo ratings yet

- Punnett Square Practice Worksheet (Edited) PDFDocument4 pagesPunnett Square Practice Worksheet (Edited) PDFImie guzmanNo ratings yet

- T H 091 The Great Fire of London Quiz PowerpointDocument19 pagesT H 091 The Great Fire of London Quiz Powerpointapi-353928812No ratings yet

- SR - No. Name Contact NumberDocument3 pagesSR - No. Name Contact NumberRahul PatelNo ratings yet

- Reflection Paper Outbreak Movie QuestionsDocument3 pagesReflection Paper Outbreak Movie QuestionsNicoleFrias100% (1)

- The Human Digestion ProcessDocument7 pagesThe Human Digestion ProcessRayyan Anthony AbasNo ratings yet

- ASTR342 Seminar Paper Winter 2023 8Document4 pagesASTR342 Seminar Paper Winter 2023 82210412310016No ratings yet

- Britten-The Rape of Lucretia LibrettoDocument18 pagesBritten-The Rape of Lucretia Librettopocarmen100% (1)

- The Clever Hare: CCSS. RL.3.2 - ©Document3 pagesThe Clever Hare: CCSS. RL.3.2 - ©Nurlaila Talib100% (1)

- Pet AgreementDocument2 pagesPet AgreementwestviewkelownaNo ratings yet

- Propuesta en Idioma Ingles de Un Producto o ServicioDocument9 pagesPropuesta en Idioma Ingles de Un Producto o ServicioOliver Eudan Bolaños SilvaNo ratings yet

- Animales (Animals) en InglesDocument2 pagesAnimales (Animals) en InglesTotono BraYan IINo ratings yet

- Animalandfishraising6 180729105611Document80 pagesAnimalandfishraising6 180729105611Marvin CeballosNo ratings yet

- A Q U A C U L T U R eDocument6 pagesA Q U A C U L T U R eChel GualbertoNo ratings yet

- Question of The ReadingDocument2 pagesQuestion of The Readingapi-369037100No ratings yet

- Bionike IntimateDocument8 pagesBionike IntimateManolo RozalénNo ratings yet

- Stoma Care 01Document13 pagesStoma Care 01raquel maniegoNo ratings yet

- Medical Emergencies and First AidDocument54 pagesMedical Emergencies and First AidCeleste Coronel Dela Cruz100% (2)

- Necrotizing Ulcerative PeriodontitisDocument15 pagesNecrotizing Ulcerative PeriodontitisPoushya Riceg0% (1)

- Glandular Type DietDocument4 pagesGlandular Type DietRosa María Rodríguez de PaoliNo ratings yet

- Neurophysiology WhinneryDocument5 pagesNeurophysiology WhinneryParvez KaleemNo ratings yet

- Gabapentina en GatosDocument9 pagesGabapentina en GatosSócrates MillmanNo ratings yet

- Handouts in HYGIENE Hygiene - Is The Science of Health and Its MaintenanceDocument9 pagesHandouts in HYGIENE Hygiene - Is The Science of Health and Its MaintenanceTweetie Borja DapogNo ratings yet

- Saranagatigadya TamilDocument5 pagesSaranagatigadya TamilraliumNo ratings yet

- Christmas with His Cinderella: A captivating fairytale romance!From EverandChristmas with His Cinderella: A captivating fairytale romance!Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Welfare of Performing AnimalsDocument292 pagesWelfare of Performing AnimalsИгор Галоски50% (2)

- Eptatretus Indrambaryai, A New Species of Hagfish (Myxinidae) From The Andaman SeaDocument13 pagesEptatretus Indrambaryai, A New Species of Hagfish (Myxinidae) From The Andaman SeaoonthaiNo ratings yet

- REPORT TEXT Bahasa Inggris Bab IX KelasDocument14 pagesREPORT TEXT Bahasa Inggris Bab IX KelasErick JonNo ratings yet

- ElvesDocument3 pagesElvesCesar ManNo ratings yet

- February 2021 Cbse Reading Challenge 2.O: Paper Code (Rce-1)Document14 pagesFebruary 2021 Cbse Reading Challenge 2.O: Paper Code (Rce-1)SUNIL TPNo ratings yet

- A Murder of Crows: Seventeen Tales of Monster & The MacabreFrom EverandA Murder of Crows: Seventeen Tales of Monster & The MacabreNo ratings yet