Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Pediatrics in Review 2001 Hughes 191 7

Uploaded by

Edward LimantaraOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Pediatrics in Review 2001 Hughes 191 7

Uploaded by

Edward LimantaraCopyright:

Available Formats

Otitis Externa Emma Hughes and Jeffrey H. Lee Pediatrics in Review 2001;22;191 DOI: 10.1542/pir.

22-6-191

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is located on the World Wide Web at: http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/content/22/6/191

Data Supplement (unedited) at: http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/content/suppl/2005/01/27/22.6.191.DC1.html

Pediatrics in Review is the official journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics. A monthly publication, it has been published continuously since 1979. Pediatrics in Review is owned, published, and trademarked by the American Academy of Pediatrics, 141 Northwest Point Boulevard, Elk Grove Village, Illinois, 60007. Copyright 2001 by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0191-9601.

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ at Indonesia:AAP Sponsored on April 26, 2012

Article

infectious disease

Otitis Externa

Emma Hughes, MD,* and Jeffrey H. Lee, MD*

Objectives

1. 2. 3. 4.

After completing this article, readers should be able to:

Dene otitis externa and describe the typical signs and symptoms. Name several risk factors for the development of otitis externa. Describe the microbiology of otitis externa. Describe the principles of treatment and review some of the recommended ototopical medications and their side effects.

Introduction

Otitis externa (OE) is a broad term that includes inammation or infection of the external auditory canal. It can range from a mild inammation to a potentially life-threatening disease in older adults, otherwise known as necrotizing otitis externa. Crucial to an accurate and timely diagnosis of the spectrum of otitis externa is a thorough understanding of the anatomy and physiology of the external ear canal as well as knowledge of pertinent microbiology and clinical presentation. Acute (diffuse) otitis externa is the most common infection of the external auditory canal. It is known also as swimmers ear, tropical ear, or Singapore ear.

Denition and Epidemiology

The symptoms of acute diffuse OE include pruritus, pain, and tenderness to palpation. As the process progresses, a sensation of fullness and hearing loss can occur. Chewing and moving the jaw often exacerbate otalgia. Signs include erythema and edema of the external auditory canal that can spread to the concha and tragus if severe. Secretions and otorrhea as well as crusting of the external auditory canal are typical. Palpation and manipulation of the pinna and tragus elicit pain. Acute OE usually occurs during the summer months in more temperate climates or at any time of year in warm climates. In general, it occurs with higher frequency in warm, humid climates. Approximately 10% of people suffer from acute OE at some point; 90% of cases are unilateral. Risk factors for the development of acute OE include increased environmental temperature, high humidity, maceration of the skin, local trauma, exposure to water that has high bacterial counts, and swimming. Moisture in the canal raises the pH and leads to edema and maceration of the epithelial lining. Other factors that may play a role include excessive sweating, absence of cerumen, a narrow or long external auditory canal, alkaline pH, and hearing aid use. Lack of cerumen predisposes to infection in several ways. Cerumen provides an acidic coat that protects the skin against pathogens and contains certain antimicrobial components such as lysozyme. In addition, removal of cerumen may abrade the skin of the external auditory canal. Whether the cleanliness of the water in which swimming occurs inuences the likelihood of OE following exposure to pools, lakes, or other bodies of water is controversial. In some studies, the presence of bacteria in pools did not correlate signicantly with the development of OE; the pH of the pool seemed to play a more important role. However, other researchers who have examined bacterial counts in lakes have found an increased incidence of OE associated with lakes that have high bacterial counts. Other potential sources of water contamination include whirlpools, hot tubs, and pressurized ear irrigation.

*University of Rochester School of Medicine & Dentistry, Rochester, NY. Pediatrics in Review Vol.22 No.6 June 2001 191

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ at Indonesia:AAP Sponsored on April 26, 2012

infectious disease otitis externa

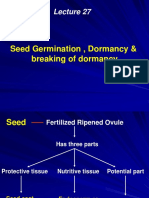

Figure. Diagram of the ear.

Anatomy and Physiology

The external ear is composed of the pinna and external auditory canal (Figure). The pinna is comprised of an elastic cartilaginous frame. The canal is approximately 2.5 cm in length and is composed of a lateral (1/3) cartilaginous portion and a medial (2/3) osseous portion. The lateral cartilaginous portion is oriented superiorly and posteriorly and contains hair follicles, sebaceous glands, and apocrine (ceruminous) glands that produce cerumen, a combination of secretions from the glands mixed with desquamated epithelial cells. Of note, the anterior, inferior aspect of the cartilaginous portion has vertical ssures (ssures of Santorini) that form a potential conduit for the spread of infection or neoplasm from the external auditory canal to the parotid gland, preauricular soft tissue, and temporomandibular joint. The medial bony portion is oriented inferiorly and anteriorly and is covered by tightly adherent epithelium devoid of adnexal structures. Squamous epithelium lines the surface of the external auditory canal as well as the lateral surface of the tympanic membrane and migrates laterally, carrying the cerumen toward the lateral orice.

with or without debris. Moderate inammation follows, with the development of increased pain and edema as well as seropurulent material. Severe otitis externa involves a canal lumen that is obstructed and draining secretions and debris. Sagging of the superior canal, periauricular edema, and adenopathy can develop. The pain often is intense, especially with chewing or tragal manipulation. In severe cases, the infection may extend to surrounding soft tissue and lymph nodes. Infection can spread through the ssures of Santorini to the parotid gland and toward the temporomandibular joint. Posterior spread to connective tissue overlying the mastoid bone occurs through the cartilaginous canal. Medial spread to the infratemporal fossa leads to involvement of cranial bones and possibly to osteomyelitis of the base of the skull. Chronic inammatory OE is a persistent lowgrade infection and inammation. It is important to determine whether a canal infection is simply OE or is secondary to acute otitis media (AOM) with perforation or to chronic suppurative OM (CSOM) with or without cholesteatoma. Table 1 describes features of the history and physical examination that may help to distinguish these entities. It is essential to attempt to visualize the tympanic membrane, although it is not always possible to see. Draining AOM requires oral antibiotics and further management. Follow-up becomes important if visualization is not possible and there is suspicion that another process is involved or if the acute localized OE is not responding as expected to treatment.

Microbiology

The most common organisms found in a healthy ear are Staphylococcus epidermidis, Corynebacterium sp, and alpha-hemolytic Streptococcus. The organisms primarily causing acute OE are Pseudomonas aeruginosa and S aureus. Aspergillus niger is the primary pathogen in otomycosis (fungal OE). Table 2 lists the bacteria found in healthy hosts and in patients who have OE. Some researchers have demonstrated the polymicrobial nature of OE in one third of patients and the role of anaerobic bacteria in one quarter, emphasizing the need to obtain both anaerobic and aerobic cultures in patients who have OE that does not respond to treatment.

Pathogenesis and Clinical Findings

Three clinical stages of OE have been described: preinammatory; acute inammatory, including mild, moderate, and severe forms; and chronic. In the preinammatory stage, moisture or local trauma removes the lipid layer protecting the skin. The skin then becomes edematous, which obstructs the glands, and is followed by a sensation of aural fullness and itching. This process predisposes the ear to continued trauma. In mild acute inammatory OE, the canal becomes edematous and erythematous and develops clear, odorless secretions

192 Pediatrics in Review Vol.22 No.6 June 2001

Management

Management aims at controlling infection and inammation. Gentle cleansing of the canal and avoidance of water, humidity, and skin maceration all promote healing. Swimming should be prohibited during the course of treatment. Installation of ototopical medications should follow appropriate cleansing of the canal. If the

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ at Indonesia:AAP Sponsored on April 26, 2012

infectious disease otitis externa

Table 1.

Distinguishing Features of Three Types of Otitis Infections

Otitis Externa (OE) Acute Otitis Media (OM) With Perforation Present; may note relief after perforation May be present Winter/spring Purulent; noted after perforation Upper respiratory tract infection; history of OM Debris in canal; edema, erythema, tenderness depend on degree of secondary OE Perforation; red, opaque/ purulent drainage behind TM Chronic Suppurative Otitis Media Rare Rare Variable Purulent; persists >2 wk Perforation of tympanic membrane; recurrent OM Chronic inammation; debris in canal Perforation secondary to OM or tympanostomy tubes Pseudomonas aeruginosa; Staphylococcus aureus

History Pain Fever Season Drainage Associations Physical Examination Ear canal Tympanic Membrane (TM) Microbiology

Present; may be severe; also pruritis Uncommon Summer Mucopurulent; progresses with pain Swimming

Edematous, erythematous, tender; tragus/pinna tender Usually normal

Pseudomonas aeruginosa; Staphylococcus aureus

Streptococcus pneumoniae; Haemophilus inuenzae

infection is recurrent or persistent, cultures should be obtained. Adequate analgesia is an important adjunctive therapy. Early OE may be treated with acidifying agents and local care alone, but it also responds well to topical antibiotics. Mild-to-moderate OE is treated with debridement and antibiotic or acidic drops. Double-blind, controlled studies of acetic acid or propylene glycol eardrops compared with antibiotic preparations showed no signicant difference. Oral antimicrobial agents are indicated in severe cases of OE that have progressed to cellulitis of surrounding structures or lymphadenitis. Treatment typically is 10 days of an antipseudomonal antibiotic in adults or an antistaphylococcal drug such as cephalexin in children. Fluoroquinolones, a common choice in adults, are not approved for use in children younger than 18 years of age because studies in young dogs documented cartilaginous damage after use of uoroquinolones. Topical use of these agents, however, is considered safe because systemic absorption is minimal. Persistent inammation despite the use of antimicrobials poses a diagnostic challenge. Medications containing neomycin may cause an allergic contact dermatitis in approximately 5% of recipients. Treatment of that condition consists of discontinuing the neomycin and adding topical steroid cream or a debriding shampoo. The canal should be cultured and the ototopical formulation changed. Persistent or recurrent OE that does not re-

spond to usual treatments suggests the need to consider alternative diagnoses, including CSOM, cholesteatoma, necrotizing OE, otomycosis, and rarer disorders such as Langerhans cell histiocytosis. More specic treatments of other forms of OE are included in the discussion of each subtype.

Ototopical Medications

In principle, the purposes of ototopical medications are to reduce inammation, lower the pH of the canal, and eliminate the causative organisms. Classes of ototopical medications include steroids, acidifying agents, antiseptics, and antibiotics. The preparations used most commonly are suspensions and solutions (Table 3). Drops are instilled into the ear (or onto a wick if there is severe inammation and edema) three to four times a day for 7 to 10 days. If a wick is placed, it usually is removed after 24 to 72 hours. The dosing for newer uoroquinolone antibiotics typically is 3 drops twice a day for 7 days (ciprooxacin/hydrocortisone) and 5 to 10 drops (5 drops for patients 12 y and younger) twice a day for 10 days (ooxacin). Most pathogenic organisms grow best in an alkaline environment. For this reason, otic preparations are acidic, with a pH of 3.0 to 6.0. Although acidic solutions inhibit the growth of bacteria, they may cause local irritation and burning. Suspensions (pH, 5.0) usually are less irritating than solutions (pH, 3.0 to 4.0). If the patient is unable to tolerate otic preparations, an ophPediatrics in Review Vol.22 No.6 June 2001 193

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ at Indonesia:AAP Sponsored on April 26, 2012

infectious disease otitis externa

Microorganisms Isolated From the Ear Canal in Health and Disease*

Table 2.

Organism

Normal 3 2 2 2 2 to 4

a

External Otitis Media 1 1 1 2 ?

Staphylococcus epidermidis Corynebacteria Alpha-hemolytic streptococci Staphylococcus aureus Anaerobic bacteria Escherichia coli, Proteus sp Klebsiella, Enterobacter sp Pseudomonas Aspergillus, Candida sp

a b c

and guinea pig, and the human ear. Also, the edema and inammation that accompany infection most likely decrease the permeability of the round window and may even decrease the penetration of topical agents into the canal. One review found only four cases of sensorineural hearing loss potentially attributable to ototopical medications in the English literature. Another survey found that 95% of otolaryngologists use these topical medications in patients who have nonintact tympanic membranes. Of those interviewed, only 3.4% reported witnessing ototoxicity from ototopical preparations. Although these agents should be used with caution, their history of extensive use with very little evidence of ototoxicity is reassuring.

Complications and Sequelae

1 1 1 2 3 1 to 4 to 3

b c

Complications of OE range from minor involvement of local structures to serious extension of infection, with progression to necrotizing OE. Stenosis of the ear canal, cellulitis, chondritis, and parotitis also can occur.

1 0 to 5%, 2 5% to 33%, 3 33% to 66%, 4 66% to 100% More frequent in swimmers than in nonswimmers Common only in tropical and subtropical climates *From Marcy S. External otitis due to infection. Pediatr Infect Dis. 1985;4(suppl 3):527530.

Prevention

The use of earplugs while swimming ideally decreases the amount of moisture in the ear and may be helpful in preventing OE. One study evaluated protection offered by seven different ear protectors, from cotton wool to silicone wax and polyvinyl chloride, and found that cotton wool with petroleum jelly provided the best protection, comfort, and ease of use. Use of acidic solutions such as 2% acetic acid or over-the-counter boric acid solutions to reconstitute the normal physiologic environment in the ear canal after exposure to water may be effective. Several over-thecounter preparations used as prophylaxis against swimmers ear are equivalent to a mixture of vinegar and rubbing alcohol in equal proportions. Drying the ear with a hair dryer set on low heat from 1 ft away for 60 seconds can be a helpful preventive measure. Avoiding manipulation of the ear canal will prevent local irritation and maceration of the skin. Repetitive use of cotton swabs should be avoided.

thalmic preparation that has a more neutral pH may be tolerated better. Antibiotics used in ototopical preparations include neomycin, polymyxin B, polymyxin E (colistin), and uoroquinolones. Neomycin is very active against S aureus and Proteus sp, but has no activity against Pseudomonas. The polymyxins are bactericidal against most gramnegative organisms, including Pseudomonas. Fluoroquinolones are effective against both Pseudomonas and staphylococci. Patients who do not respond well to initial treatment can be switched to drops containing ciprooxacin or tobramycin. Clotrimazole and tolnaftate may be used in the treatment of otomycosis.

Ototoxicity

Many ototopical preparations contain potentially ototoxic materials. In theory, ototoxicity may result from direct contact with structures or through systemic absorption. Potential side effects include sensorineural hearing loss, tinnitus, and vertigo. Although ototoxicity has been documented in animal studies, ototopical agents are accepted in practice and considered to be safe. It is important to note the critical differences in the anatomy of the animal models used, typically chinchilla

194 Pediatrics in Review Vol.22 No.6 June 2001

Subtypes of OE

Acute Localized OE

Acute localized OE, a form of furunculosis, is an infection of the lateral one third of the posterosuperior aspect of the external auditory canal that occurs following obstruction of an apopilosebaceous unit. The most common pathogen is S aureus. Symptoms are similar to those of acute diffuse OE and consist of pruritus and pain. Examination reveals erythema, edema, and possibly a

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ at Indonesia:AAP Sponsored on April 26, 2012

infectious disease otitis externa

Table 3.

Ototopical Medications*

Acid Acetic HCl Antiseptic Antibiotic Alcohol Alcohol Alcohol Ciprooxacin Chloramphenicol Polymyxin E/ neomycin Polymyxin B/ neomycin Polymyxin B/ neomycin Antifungal Polysorbate 80 Polysorbate 80 Steroid HTC HTC HTC HTC 1 to 12 y: 5 drops bid for 10 d >12 y: 10 drops for 10 d 4 to 6 drops q 2 to 3 h Dose 3 drops bid for 7 d 2 to 3 drops tid 5 drops tid-qid 10 d 3 drops tid-qid for 10 d 3 drops tid-qid for 10 d

Product Name Cipro HC Otic Chloromycetin Otic Colymycin S Otic Cortisporin Suspension Cortisporin Solution Cresylate Floxin Otic

M-cresyl acetate Ooxacin

Orlex HC Otic Orlex Otic Otic Domeboro Otic Neo-cort Dome Otic Tridesilon Solution Otobione Otobiotic Otocort Pediotic Pyocidin Otic VoSol Otic VoSol HC Otic

Acetic Acetic Acetic Acetic/stearic Acetic Propionic Sulfuric Acetic Acetic/citric

Alcohol Alcohol Alcohol Alcohol Alcohol Alcohol Alcohol

Neomycin Polymyxin B/ neomycin Neomycin Polymyxin B/ neomycin Polymyxin B/ neomycin Polymyxin B

Potassium sorbate Polysorbate 80

HTC HTC Desonide HTC HTC HTC HTC HTC

3 drops tid-qid for 10 d 3 drops tid-qid for 10 d 3 to 5 drops tid-qid 3 to 5 drops tid-qid

HTC hydrocortisone *Modied from Fairbanks DNF. Pocket Guide to Antimicrobial Therapy in Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 1991

focal abscess. Treatment includes incision and drainage, if needed, followed by administration of topical and oral antibiotics (antistaphylococcal penicillins or rstgeneration cephalosporins, erythromycin, or clindamycin), heat, and analgesics.

Chronic OE

Chronic OE is a persistent low-grade infection and inammation of the canal that leads to a thickening of the canal skin. Symptoms are primarily pruritus, mild discomfort, and dry, aky skin in the external canal. Examination reveals a lack of cerumen and dry, hypertrophic skin. Pain upon manipulation and otorrhea also can occur. The organisms grown from cultures in cases of chronic OE are inuenced by previous courses of antimicrobial agents, and the recovered organisms range from normal ora to pathogenic microbes. Treatment focuses

on restoring normal physiology to the canal, promoting the production of cerumen, and gently removing debris. Topical acidifying and drying agents may be helpful. Steroid preparations, including triamcinolone and dexamethasone creams or ointments, also play a role. In some cases, discontinuation of topical agents followed by observation alone may be benecial. Many recurrent cases of OE involve an underlying dermatologic disease, such as seborrheic dermatitis or eczema. Rarely, surgical reconstruction of the canal may be necessary.

Eczematous OE

Eczematous OE is a term used to describe a variety of dermatologic conditions that affect the external auditory canal; it encompasses atopic dermatitis, seborrheic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, psoriasis, and lupus. This form of OE presents primarily with pruritus and is manPediatrics in Review Vol.22 No.6 June 2001 195

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ at Indonesia:AAP Sponsored on April 26, 2012

infectious disease otitis externa

ifested by erythema, edema, scaling, and crusting. Treatment is for the primary disorder.

Otomycosis

Otomycosis, fungal OE, accounts for 10% of cases of OE. The percentage is higher in tropical climates. The patient may have a history of diabetes or immune dysfunction or recent use of systemic or topical antibiotics or steroids. The signs and symptoms are more insidious than those of bacterial OE. Physical examination reveals mild inammation and thick otorrhea, with black, gray, bluish green, yellow, or white fungal growth and debris. The most common pathogens are Aspergillus and Candida sp. Aspergillus niger accounts for 90% of infections and typically presents with a cottony base and a black powdery covering. Treatment consists of cleansing the canal and using acidifying agents and antifungal drops, such as clotrimazole. Gentian violet also can be used because it has both acidifying and antimicrobial properties.

inammation and granulation tissue at the bonycartilaginous junction. Radiographic imaging and radionuclide scanning can help establish the diagnosis. Computed tomography can help delineate soft-tissue inammation and the extent of infection and bony erosion; gallium-67 citrate is a sensitive method for identifying inammation and infection. No pediatric deaths have been reported compared with a 20% mortality rate in adults. Treatment consists of intravenous antipseudomonal antibiotics for 2 to 3 weeks and debridement. Surgery now plays a minor role in management.

Summary

OE is a general term describing inammation and infection of the external auditory meatus. It has a broad range of severity, but the most common form is acute diffuse OE, otherwise known as swimmers ear. Pseudomonas sp and S aureus are the principal microorganisms involved. Treatment focuses on restoring the physiology of the external auditory canal, reducing the inammation, and treating the infection. Topical acidifying agents, steroids, and antimicrobials form the cornerstones of treatment. The safety of certain ototopicals remains somewhat controversial, although historical experience is reassuring. Recurrent or persistent OE should prompt the consideration of alternative diagnoses and referral to a specialist in otolaryngology.

Necrotizing (Malignant) OE

Necrotizing OE is a severe variant that usually is caused by P aeruginosa and is associated with systemic invasion. Most cases have been described in elderly adults who have diabetes mellitus. To date, only 15 cases have been described in children. The pediatric population that is susceptible to necrotizing OE includes diabetic adolescents and children who have some degree of immune dysfunction, including leukemia, malnutrition, anemia, drug-induced leukopenia, immunoglobulin deciency, or solid tumors. Symptoms include acute onset of pain, discharge, a sensation of fullness, and hearing loss. Severe pain, especially at night, is common. Facial nerve paralysis occurs more frequently and earlier in the course of the disease in children than in adults. The palsy often is permanent. This predisposition in children is believed to be related to the more medial location of the bone-cartilage junction and the undeveloped mastoid process, both of which put the nerve in a more susceptible position. Physical examination shows

Suggested Reading

Bojrab D, Bruderly T, Abdulrazzak Y. Otitis externa. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1996;29:761782 Hirsch B. Diseases of the external ear. In: Bluestone CD, Stool S, Kenna M, eds. Pediatric Otolaryngology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: WB Saunders; 1996:378 387 Jones RN, Milazzo J, Seidlin M. Ooxacin otic solution for treatment of otitis externa in children and adults. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;123:11931200 Pelton SI, Klein JO. The draining ear: otitis media and externa. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1998;2:117128 Rubin J, Yu V, Stool S. Malignant external otitis in children. J Pediatr. 1988;113:965970.

196 Pediatrics in Review Vol.22 No.6 June 2001

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ at Indonesia:AAP Sponsored on April 26, 2012

infectious disease otitis externa

PIR Quiz

Quiz also available online at www.pedsinreview.org. 6. Which of the following statements about otitis externa is true? A. B. C. D. E. Hearing loss can occur in severe cases. Otorrhea is uncommon. Prevention is best accomplished by using cotton swabs frequently after swimming. Swimming in pools rather than lakes increases the risk of developing otitis externa. The presence of increased cerumen in the external auditory canals increases the risk of developing otitis externa.

7. Which organism is most likely to cause acute otitis externa in a healthy host? A. B. C. D. E.

Aspergillus niger. Candida sp. Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Staphylococcus epidermidis. Streptococcus pneumoniae.

8. A mother brings her 3-year-old son to you because of ear drainage for 2 days. She is concerned that he may have an ear infection. Which of the following is most likely to help distinguish between otitis externa and otitis media with perforation? A. B. C. D. E. Ear pain. Edema of the canal. Lack of fever. Purulent secretions. Tenderness on palpation of the pinna.

9. You have diagnosed moderate acute otitis externa in a 10-year-old girl who is on the school swim team. Which of the following is true regarding her management? A. B. C. D. E. A preparation of topical uoroquinolone and hydrocortisone is most appropriate. Acetic acid eardrops are superior to antibiotic eardrops. Oral cephalexin is indicated. She may continue to swim during her course of therapy. Tinnitus and vertigo are common side effects with topical therapy.

10. Which of the following statements regarding subtypes of otitis externa is true? A. B. C. D. E.

Candida sp are the most common organisms to cause fungal otitis externa. Facial nerve paralysis is common among children who have necrotizing otitis externa. Otomycosis should be treated with oral antifungal agents. Steroids have not been shown to be helpful for chronic otitis externa. The treatment of choice for necrotizing otitis externa is surgical reconstruction of the canal.

Pediatrics in Review Vol.22 No.6 June 2001 197

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ at Indonesia:AAP Sponsored on April 26, 2012

Otitis Externa Emma Hughes and Jeffrey H. Lee Pediatrics in Review 2001;22;191 DOI: 10.1542/pir.22-6-191

Updated Information & Services References

including high resolution figures, can be found at: http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/content/22/6/191 This article cites 2 articles, 0 of which you can access for free at: http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/content/22/6/191#BIBL

Permissions & Licensing

Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or in its entirety can be found online at: /site/misc/Permissions.xhtml Information about ordering reprints can be found online: /site/misc/reprints.xhtml

Reprints

Downloaded from http://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/ at Indonesia:AAP Sponsored on April 26, 2012

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Head to Toe Physical Assessment GuideDocument16 pagesHead to Toe Physical Assessment Guideabagatsing100% (5)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- General Zoology SyllabusDocument4 pagesGeneral Zoology SyllabusNL R Q DO100% (3)

- Chapter 3 Science Form 4Document30 pagesChapter 3 Science Form 4Shafie BuyaminNo ratings yet

- Seed Germination, Dormancy & Breaking of DormancyDocument35 pagesSeed Germination, Dormancy & Breaking of DormancySaravananNo ratings yet

- H2S Training Slides ENGLISHDocument46 pagesH2S Training Slides ENGLISHf.B100% (1)

- Worksheet - Dna Protein SynthesisDocument2 pagesWorksheet - Dna Protein Synthesisapi-270403367100% (1)

- L.D..Occlusion in FPDDocument138 pagesL.D..Occlusion in FPDApurva Deshmukh67% (3)

- Muscles of Mastication Functions and Clinical SignificanceDocument130 pagesMuscles of Mastication Functions and Clinical SignificanceDevanand GuptaNo ratings yet

- Answer Key For Comprehensive Exam XVDocument18 pagesAnswer Key For Comprehensive Exam XVQharts SajiranNo ratings yet

- Thalassemia: SymptomsDocument3 pagesThalassemia: SymptomsAndi BandotNo ratings yet

- Management of Clients With Disturbances in OxygenationDocument13 pagesManagement of Clients With Disturbances in OxygenationClyde CapadnganNo ratings yet

- Mitosis and MeiosisDocument4 pagesMitosis and MeiosisMicah Porcal ArelladoNo ratings yet

- ADDISONS DSE - Etio Trends&Issues + DSDocument9 pagesADDISONS DSE - Etio Trends&Issues + DSgraceNo ratings yet

- BioSignature Review - Are Hormones The Key To Weight LossDocument19 pagesBioSignature Review - Are Hormones The Key To Weight LossVladimir OlefirenkoNo ratings yet

- Body WeightDocument23 pagesBody WeightIkbal NurNo ratings yet

- LAB EXERCISE 1 Organization of The Human BodyDocument8 pagesLAB EXERCISE 1 Organization of The Human Bodyley leynNo ratings yet

- B CellDocument10 pagesB CellSonia Elizabeth SimonNo ratings yet

- The Anterior Cranial FossaDocument4 pagesThe Anterior Cranial FossaArshad hussainNo ratings yet

- Worksheet: I) Ii) Iii)Document4 pagesWorksheet: I) Ii) Iii)Jin MingNo ratings yet

- CorneaDocument41 pagesCorneaNikhil KorripatiNo ratings yet

- The Management of Intra Abdominal Infections From A Global Perspective 2017 WSES Guidelines For Management of Intra Abdominal InfectionsDocument34 pagesThe Management of Intra Abdominal Infections From A Global Perspective 2017 WSES Guidelines For Management of Intra Abdominal InfectionsJuan CastroNo ratings yet

- Nicotrol InhalerDocument19 pagesNicotrol InhalerdebysiskaNo ratings yet

- 201305283en Capsurefix 5076Document2 pages201305283en Capsurefix 5076Bian PurwaNo ratings yet

- A Kinesiological Analysis of Shot BY WILLISDocument16 pagesA Kinesiological Analysis of Shot BY WILLISNoraina AbdullahNo ratings yet

- ANAESTHESIOLOGYDocument38 pagesANAESTHESIOLOGYcollinsmagNo ratings yet

- Assignment Lec 4Document3 pagesAssignment Lec 4morriganNo ratings yet

- Sri Padmavathi Medical College Hospital: APPLICATIONS Are INVITED For The Following Post - 2013-14Document3 pagesSri Padmavathi Medical College Hospital: APPLICATIONS Are INVITED For The Following Post - 2013-14Birupakshya RoutNo ratings yet

- Chronic Kidney Disease : Hypertensive and Diabetic Retinopathy in PatientsDocument7 pagesChronic Kidney Disease : Hypertensive and Diabetic Retinopathy in PatientsAnonymous FgT04krgymNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4Document7 pagesChapter 4R LashNo ratings yet

- Phylum Arthropoda - Why such abundance and diversityDocument4 pagesPhylum Arthropoda - Why such abundance and diversitySHILNo ratings yet