31/7/25, 6:38 π.μ.

Natural nuclear fission reactor - Wikipedia

Natural nuclear fission reactor

A natural nuclear fission reactor is a uranium deposit where self-sustaining nuclear chain

reactions occur. The idea of a nuclear reactor existing in situ within an ore body moderated by

groundwater was briefly explored by Paul Kuroda in 1956.[1] The existence of an extinct or fossil

nuclear fission reactor, where self-sustaining nuclear reactions occurred in the past, was

established by analysis of isotope ratios of uranium and of the fission products (and the stable

daughter nuclides of those fission products). The first discovery of such a reactor happened in 1972

in Oklo, Gabon, by researchers from the French Alternative Energies and Atomic Energy

Commission (CEA) when chemists performing quality control for the French nuclear industry

235

noticed sharp depletions of fissile U in gaseous uranium hexafluoride made from Gabonese ore.

Oklo is the only location where this phenomenon is known to have occurred, and consists of 16

sites with patches of centimeter-sized ore layers. There, self-sustaining nuclear fission reactions

are thought to have taken place approximately 1.7 billion years ago, during the Statherian period of

the Paleoproterozoic. Fission in the ore at Oklo continued off and on for a few hundred thousand

years and probably never exceeded 100 kW of thermal power.[2][3][4] Life on Earth at this time

consisted largely of sea-bound algae and the first eukaryotes, living under a 2% oxygen

atmosphere. However, even this meager oxygen was likely essential to the concentration of

uranium into fissionable ore bodies, as uranium dissolves in water only in the presence of oxygen.

Before the planetary-scale production of oxygen by the early photosynthesizers groundwater-

moderated natural nuclear reactors are not thought to have been possible.[4]

Discovery of the Oklo fossil reactors

In May 1972, at the Tricastin uranium enrichment site at Pierrelatte, France, routine mass

spectrometry comparing UF6 samples from the Oklo mine showed a discrepancy in the amount of

235 235

the U isotope. Where the usual concentrations of U were 0.72% the Oklo samples showed

235

only 0.60%. This was a significant difference—the samples bore 17% less U than expected.[5]

This discrepancy required explanation, as all civilian uranium handling facilities must

meticulously account for all fissionable isotopes to ensure that none are diverted into the

construction of unsanctioned nuclear weapons. Further, as fissile material is the reason for mining

uranium in the first place, the missing 17% was also of direct economic concern.

[Link] 1/8

�31/7/25, 6:38 π.μ. Natural nuclear fission reactor - Wikipedia

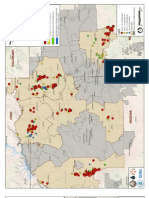

Geological situation in Gabon leading to

natural nuclear fission reactors

1. Nuclear reactor zones

2. Sandstone

3. Uranium ore layer

4. Granite

Thus, the French Alternative Energies and Atomic Energy Commission (CEA) began an

investigation. A series of measurements of the relative abundances of the two most significant

isotopes of uranium mined at Oklo showed anomalous results compared to those obtained for

uranium from other mines. Further investigations into this uranium deposit discovered uranium

235

ore with a U concentration as low as 0.44% (almost 40% below the normal value). Subsequent

examination of isotopes of fission products such as neodymium and ruthenium also showed

anomalies, as described in more detail below. However, the trace radioisotope 234U did not deviate

significantly in its concentration from other natural samples. Both depleted uranium and

reprocessed uranium will usually have 234U concentrations significantly different from the secular

equilibrium of 55 ppm 234U relative to 238U. This is due to 234U being enriched together with 235U

and due to it being both consumed by neutron capture and produced from 235U by fast-neutron-

induced (n,2n) reactions in nuclear reactors. In Oklo, any possible deviation of 234U concentration

present at the time the reactor was active would have long since decayed away. 236U must have

also been present in higher-than-usual ratios during the time the reactor was operating, but due to

its half-life of 2.348 × 107 years being almost two orders of magnitude shorter than the time

elapsed since the reactor operated, it has decayed to roughly 1.4 × 10−22 its original value and

below any abilities of current equipment to detect.

235

This loss in U is exactly what happens in a nuclear reactor. A possible explanation was that the

uranium ore had operated as a natural fission reactor in the distant geological past. Other

observations led to the same conclusion, and on 25 September 1972, the CEA announced their

finding that self-sustaining nuclear chain reactions had occurred on Earth about 2 billion years

ago. Later, other natural nuclear fission reactors were discovered in the region.[4]

Nd 143 144 145 146 148 150

C/M 0.99 1.00 1.00 1.01 0.98 1.06

[Link] 2/8

�31/7/25, 6:38 π.μ. Natural nuclear fission reactor - Wikipedia

Fission product isotope signatures

235

Isotope signatures of natural neodymium and fission product neodymium from U

which had been subjected to thermal neutrons.

Neodymium

The neodymium found at Oklo has a different isotopic composition to that of natural neodymium:

142 142

the latter contains 27% Nd, while that of Oklo contains less than 6%. The Nd is not produced

142

by fission; the ore contains both fission-produced and natural neodymium. From this Nd

content, we can subtract the natural neodymium and gain access to the isotopic composition of

235 143 145

neodymium produced by the fission of U. The two isotopes Nd and Nd lead to the

144 146

formation of Nd and Nd by neutron capture. This excess must be corrected (see above) to

obtain agreement between this corrected isotopic composition and that deduced from fission

yields.

[Link] 3/8

�31/7/25, 6:38 π.μ. Natural nuclear fission reactor - Wikipedia

Ruthenium

235

Isotope signatures of natural ruthenium and fission product ruthenium from U

100

which had been subjected to thermal neutrons. The Mo (an extremely long-lived

100

double beta emitter) has not had time to decay to Ru in more than trace

quantities over the time since the reactors stopped working.

99

Similar investigations into the isotopic ratios of ruthenium at Oklo found a much higher Ru

concentration than otherwise naturally occurring (27–30% vs. 12.7%). This anomaly could be

99 99

explained by the decay of Tc to Ru. In the bar chart, the normal natural isotope signature of

ruthenium is compared with that for fission product ruthenium which is the result of the fission of

235

U with thermal neutrons. The fission ruthenium has a different isotope signature. The level of

100

Ru in the fission product mixture is low because fission produces neutron rich isotopes which

100

subsequently beta decay and Ru would only be produced in appreciable quantities by double

beta decay of the very long-lived (half-life 7.1 × 1018 years) molybdenum isotope 100Mo. On the

100

timescale of when the reactors were in operation, very little (about 0.17 ppb) decay to Ru will

have occurred. Other pathways of 100 99 99

Ru production like neutron capture in Ru or Tc (quickly

followed by beta decay) can only have occurred during high neutron flux and thus ceased when the

fission chain reaction stopped.

Mechanism

The natural nuclear reactor at Oklo formed when a uranium-rich mineral deposit became

inundated with groundwater, which could act as a moderator for the neutrons produced by nuclear

fission. A chain reaction took place, producing heat that caused the groundwater to boil away;

without a moderator that could slow the neutrons, however, the reaction slowed or stopped. The

reactor thus had a negative void coefficient of reactivity, something employed as a safety

mechanism in human-made light water reactors. After cooling of the mineral deposit, the water

returned, and the reaction restarted, completing a full cycle every 3 hours. The fission reaction

cycles continued for hundreds of thousands of years and ended when the ever-decreasing fissile

materials, coupled with the build-up of neutron poisons, no longer could sustain a chain reaction.

[Link] 4/8

�31/7/25, 6:38 π.μ. Natural nuclear fission reactor - Wikipedia

Fission of uranium normally produces five known isotopes of the fission-product gas xenon; all

five have been found trapped in the remnants of the natural reactor, in varying concentrations.

The concentrations of xenon isotopes, found trapped in mineral formations 2 billion years later,

make it possible to calculate the specific time intervals of reactor operation: approximately 30

minutes of criticality followed by 2 hours and 30 minutes of cooling down (exponentially

decreasing residual decay heat) to complete a 3-hour cycle.[6] Xenon-135 is the strongest known

neutron poison. However, it is not produced directly in appreciable amounts but rather as a decay

product of iodine-135 (or one of its parent nuclides). Xenon-135 itself is unstable and decays to

caesium-135 if not allowed to absorb neutrons. While caesium-135 is relatively long lived, all

caesium-135 produced by the Oklo reactor has since decayed further to stable barium-135.

Meanwhile, xenon-136, the product of neutron capture in xenon-135 decays extremely slowly via

double beta decay and thus scientists were able to determine the neutronics of this reactor by

calculations based on those isotope ratios almost two billion years after it stopped fissioning

uranium.

Change of content of Uranium-235 in natural

uranium; the content was 3.65% 2 billion years

ago.

A key factor that made the reaction possible was that, at the time the reactor went critical

235

1.7 billion years ago, the fissile isotope U made up about 3.1% of the natural uranium, which is

238

comparable to the amount used in some of today's reactors. (The remaining 96.9% was U and

235

roughly 55 ppm 234U, neither of which is fissile by slow or moderated neutrons.) Because U has

238 235

a shorter half-life than U, and thus decays more rapidly, the current abundance of U in

natural uranium is only 0.72%. A natural nuclear reactor is therefore no longer possible on Earth

without heavy water or graphite.[7]

The Oklo uranium ore deposits are the only known sites in which natural nuclear reactors existed.

Other rich uranium ore bodies would also have had sufficient uranium to support nuclear

reactions at that time, but the combination of uranium, water, and physical conditions needed to

support the chain reaction was unique, as far as is currently known, to the Oklo ore bodies. It is

also possible that other natural nuclear fission reactors were once operating but have since been

geologically disturbed so much as to be unrecognizable, possibly even "diluting" the uranium so far

that the isotope ratio would no longer serve as a "fingerprint". Only a small part of the continental

[Link] 5/8

�31/7/25, 6:38 π.μ. Natural nuclear fission reactor - Wikipedia

crust and no part of the oceanic crust reaches the age of the deposits at Oklo or an age during

which isotope ratios of natural uranium would have allowed a self-sustaining chain reaction with

water as a moderator.

Another factor which probably contributed to the start of the Oklo natural nuclear reactor at

2 billion years, rather than earlier, was the increasing oxygen content in the Earth's atmosphere.[4]

235

Uranium is naturally present in the rocks of the earth, and the abundance of fissile U was at

least 3% or higher at all times prior to reactor startup. Uranium is soluble in water only in the

presence of oxygen. Therefore, increasing oxygen levels during the aging of the Earth may have

allowed uranium to be dissolved and transported with groundwater to places where a high enough

concentration could accumulate to form rich uranium ore bodies. Without the new aerobic

environment available on Earth at the time, these concentrations probably could not have taken

place.

It is estimated that nuclear reactions in the uranium in centimeter- to meter-sized veins consumed

235

about five tons of U and elevated temperatures to a few hundred degrees Celsius.[4][8] Most of

the non-volatile fission products and actinides have only moved centimeters in the veins during

the last 2 billion years.[4] Studies have suggested this as a useful natural analogue for nuclear

waste disposal.[9] The overall mass defect from the fission of five tons of 235U is about 4.6

kilograms (10 lb). Over its lifetime the reactor produced roughly 100 megatonnes of TNT (420 PJ)

in thermal energy, including neutrinos. If one ignores fission of plutonium (which makes up

roughly a third of fission events over the course of normal burnup in modern human-made light

water reactors), then fission product yields amount to roughly 129 kilograms (284 lb) of

technetium-99 (since decayed to ruthenium-99), 108 kilograms (238 lb) of zirconium-93 (since

decayed to niobium-93), 198 kilograms (437 lb) of caesium-135 (since decayed to barium-135, but

the real value is probably lower as its parent nuclide, xenon-135, is a strong neutron poison and

135

will have absorbed neutrons before decaying to Cs in some cases), 28 kilograms (62 lb) of

palladium-107 (since decayed to silver), 86 kilograms (190 lb) of strontium-90 (long since decayed

to zirconium), and 185 kilograms (408 lb) of caesium-137 (long since decayed to barium).

Relation to the atomic fine-structure constant

The natural reactor of Oklo has been used to check if the atomic fine-structure constant α might

have changed over the past 2 billion years. That is because α influences the rate of various nuclear

149 150

reactions. For example, Sm captures a neutron to become Sm, and since the rate of neutron

capture depends on the value of α, the ratio of the two samarium isotopes in samples from Oklo

can be used to calculate the value of α from 2 billion years ago.

Several studies have analysed the relative concentrations of radioactive isotopes left behind at

Oklo, and most have concluded that nuclear reactions then were much the same as they are today,

which implies that α was the same too.[10][11][12]

See also

Deep geological repository

Geology of Gabon

[Link] 6/8

�31/7/25, 6:38 π.μ. Natural nuclear fission reactor - Wikipedia

Mounana

References

1. Kuroda, P. K. (1956). "On the Nuclear Physical Stability of the Uranium Minerals" ([Link]

[Link]/Kuroda%[Link]) (PDF). Journal of Chemical Physics. 25 (4): 781–782,

1295–1296. Bibcode:1956JChPh..25..781K ([Link]

5..781K). doi:10.1063/1.1743058 ([Link]

2. Meshik, A. P. (November 2005). "The Workings of an Ancient Nuclear Reactor" ([Link]

[Link]/[Link]?id=ancient-nuclear-reactor). Scientific American. 293 (5): 82–86, 88, 90–

91. Bibcode:2005SciAm.293e..82M ([Link]

M). doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1105-82 ([Link]

82). PMID 16318030 ([Link]

3. Mervin, Evelyn (July 13, 2011). "Nature's Nuclear Reactors: The 2-Billion-Year-Old Natural

Fission Reactors in Gabon, Western Africa" ([Link]

tures-nuclear-reactors-the-2-billion-year-old-natural-fission-reactors-in-gabon-western-africa/).

[Link]. Retrieved July 7, 2017.

4. Gauthier-Lafaye, F.; Holliger, P.; Blanc, P.-L. (1996). "Natural fission reactors in the Franceville

Basin, Gabon: a review of the conditions and results of a "critical event" in a geologic system".

Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 60 (23): 4831–4852. Bibcode:1996GeCoA..60.4831G (http

s://[Link]/abs/1996GeCoA..60.4831G). doi:10.1016/S0016-7037(96)00245-1

([Link]

5. Davis, E. D.; Gould, C. R.; Sharapov, E. I. (2014). "Oklo reactors and implications for nuclear

science". International Journal of Modern Physics E. 23 (4): 1430007–236. arXiv:1404.4948 (ht

tps://[Link]/abs/1404.4948). Bibcode:2014IJMPE..2330007D ([Link]

abs/2014IJMPE..2330007D). doi:10.1142/S0218301314300070 ([Link]

218301314300070). ISSN 0218-3013 ([Link]

S2CID 118394767 ([Link]

6. Meshik, A. P.; et al. (2004). "Record of Cycling Operation of the Natural Nuclear Reactor in the

Oklo/Okelobondo Area in Gabon". Physical Review Letters. 93 (18): 182302.

Bibcode:2004PhRvL..93r2302M ([Link]

doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.93.182302 ([Link]

PMID 15525157 ([Link]

7. Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.).

Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 1257. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

8. De Laeter, J. R.; Rosman, K. J. R.; Smith, C. L. (1980). "The Oklo Natural Reactor: Cumulative

Fission Yields and Retentivity of the Symmetric Mass Region Fission Products". Earth and

Planetary Science Letters. 50 (1): 238–246. Bibcode:1980E&PSL..50..238D ([Link]

[Link]/abs/1980E&PSL..50..238D). doi:10.1016/0012-821X(80)90135-1 ([Link]

0.1016%2F0012-821X%2880%2990135-1).

9. Gauthier-Lafaye, F. (2002). "2 billion year old natural analogs for nuclear waste disposal: the

natural nuclear fission reactors in Gabon (Africa)" ([Link]

fr/physique/articles/10.1016/S1631-0705(02)01351-8/). Comptes Rendus Physique. 3 (7–8):

839–849. Bibcode:2002CRPhy...3..839G ([Link]

39G). doi:10.1016/S1631-0705(02)01351-8 ([Link]

901351-8).

10. New Scientist: Oklo Reactor and fine-structure value. June 30, 2004. ([Link]

[Link]/article/dn6092)

11. Petrov, Yu. V.; Nazarov, A. I.; Onegin, M. S.; Sakhnovsky, E. G. (2006). "Natural nuclear

reactor at Oklo and variation of fundamental constants: Computation of neutronics of a fresh

core". Physical Review C. 74 (6): 064610. arXiv:hep-ph/0506186 ([Link]

0506186). Bibcode:2006PhRvC..74f4610P ([Link]

4610P). doi:10.1103/PHYSREVC.74.064610 ([Link]

10). S2CID 118272311 ([Link]

[Link] 7/8

�31/7/25, 6:38 π.μ. Natural nuclear fission reactor - Wikipedia

12. Davis, Edward D.; Hamdan, Leila (2015). "Reappraisal of the limit on the variation in α implied

by the Oklo natural fission reactors". Physical Review C. 92 (1): 014319. arXiv:1503.06011 (htt

ps://[Link]/abs/1503.06011). Bibcode:2015PhRvC..92a4319D ([Link]

u/abs/2015PhRvC..92a4319D). doi:10.1103/physrevc.92.014319 ([Link]

hysrevc.92.014319). S2CID 119227720 ([Link]

Sources

Bentridi, S.E.; Gall, B.; Gauthier-Lafaye, F.; Seghour, A.; Medjadi, D. (2011). "Génèse et

évolution des réacteurs naturels d'Oklo" ([Link]

nce/articles/10.1016/[Link].2011.09.008/) [Inception and evolution of Oklo natural nuclear

reactors]. Comptes Rendus Geoscience (in French). 343 (11–12): 738–748.

Bibcode:2011CRGeo.343..738B ([Link]

doi:10.1016/[Link].2011.09.008 ([Link]

External links

The natural nuclear reactor at Oklo: A comparison with modern nuclear reactors, Radiation

Information Network, April 2005 ([Link]

[Link]/radinf/Files/[Link])

Oklo Fossil Reactors ([Link]

search/oklo/[Link])

NASA Astronomy Picture of the Day: NASA, Oklo, Fossile Reactor, Zone 15 (16 October 2002)

([Link]

( הכור הגרעיני של הטבע[Link] (in Hebrew

language)

Retrieved from "[Link]

[Link] 8/8