0% found this document useful (0 votes)

949 views60 pagesStretching For Impaired Mobility: by Ms Erum Naz

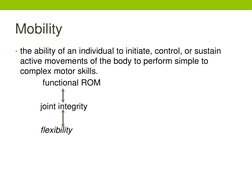

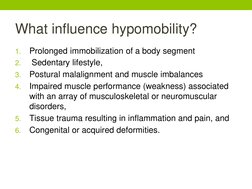

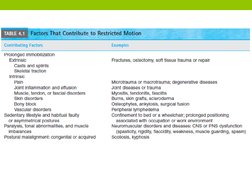

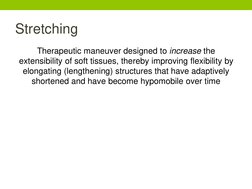

This document provides an overview of stretching techniques for improving mobility in individuals with impaired range of motion. It defines key terms like flexibility, hypomobility, and contracture. It describes the properties of soft tissues and their response to immobilization and stretching. Various types of stretching techniques are explained, including static, cyclic, ballistic, and PNF stretching. Guidelines are provided on proper alignment, stabilization, intensity, duration and frequency of stretches. Manual, mechanical and self-stretching techniques are demonstrated for the upper limbs, lower limbs and spine.

Uploaded by

Fareha KhanCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online on Scribd

0% found this document useful (0 votes)

949 views60 pagesStretching For Impaired Mobility: by Ms Erum Naz

This document provides an overview of stretching techniques for improving mobility in individuals with impaired range of motion. It defines key terms like flexibility, hypomobility, and contracture. It describes the properties of soft tissues and their response to immobilization and stretching. Various types of stretching techniques are explained, including static, cyclic, ballistic, and PNF stretching. Guidelines are provided on proper alignment, stabilization, intensity, duration and frequency of stretches. Manual, mechanical and self-stretching techniques are demonstrated for the upper limbs, lower limbs and spine.

Uploaded by

Fareha KhanCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online on Scribd