Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Interpretation of Statutes 300920-1

Uploaded by

Ranjan Baradur0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

103 views130 pagesOriginal Title

Interpretation of Statutes 300920-1.pptx

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

103 views130 pagesInterpretation of Statutes 300920-1

Uploaded by

Ranjan BaradurCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 130

Interpretation of Statutes

Basic Principles of Interpretation

• Intention of the Legislature

• Statute must be read as whole in its context

• Statute must be construed so as to make it

effective and workable

• If meaning is plain, effect must be given to it

irrespective of consequences

• Appraisal plain meaning

Intention of Legislature

• The essence of law lies in the spirit, not in its

letter, for the letter is significant only as being

the external manifestation of the intention

that underlies it” - Salmond

• Statute is the edict of the legislature

The conventional way of interpreting the

statute is to seek the intention of the

legislature

Contd..

• Courts cant interpret arbitrarily

• Duty of the court to act upon the true intention of

legislature both mens or sentia legis

• It is the short hand reference to meaning of words

as used by the legislature to be determined with the

guidance of accepted principles of interpretation

• If provision open for two meanings, the one which

represents the intention of legislature should be

taken

• It is true or legal meaning

Contd..

• Task not easy because of various reasons

• First and foremost is the language

• Words are not scientific symbols

• Language is not complete medium of

communication

• Another difficulty the legislature may not

foresee any situations or circumstances that

may emerge

contd

• Function of the court is only to expound the

law not to legislate

• Numerous rules of interpretation or

construction expressed differently by different

judges which lead to contradictory

propositions

• The problem of interpretation is problem of

meaning of words and their effectiveness to

communicating a particular thought or

expression

contd

• Words are used to refer some object or

situation

• The object to assign a technical name referent

• Words and phrases are symbols that stimulate

mental references to referents. Each word may

stand for one or a number of objects

(Language and the Law by Glanvile Williams)

• Words are capable to refer to different

referents in different contexts in times

Contd..

• Difficulty in borderline cases falling within or outside

the connotation of the word

• Language may be misunderstood in such cases

• The difference between interpretation of

communication and statute of law

• Statute cannot be explained by individual legislature

or even by a resolution as once enactment is done

the legislature become functus officio

• They can however amend or repeal any statute or

declare its meaning which can be done only through

the normal process of making the law

Contd

• Example: word Building divergent decesions by the

courts ( Open Platform without a roof or wall

considered to be a building, but a brick kiln not a

building St v Venkat Rao Krishna Rao Gujar, Intl Airport

Employees Union v. Intl Airport Authority of India, State

v. SK Roy)

• Sometimes use of general words to cover different

situations arise problems

• Another example word repair doesn’t include cleaning

and oiling ( London & North Eastern Rly Co v. Berriman)

• Notional extension of the words accident arising out

of employment (Best Undertaking v. Agnes)

Contd..

• whether a railway workman engaged in

cleaning and oiling a permanent way, is

repairing ..? Answer no by House of Lords

Berriman case

• Courts have to draw a line between the literal

and contextual meaning of the words.

• Modern day statute have a policy to curb

some public evil or mischief or effectuate

some public benefit.

• Sometimes the general words are so designed

to cover similar situations that arise in future

contd

• However not possible to anticipate fully the

future changing situations..ex. Cyber Crimes

• The duty of the court only to expound not ot

legislate is a fundamental rule, therefore only

a marginal area to mould or creatively

interpret

• Ex..Telegraph Acts of 1863 & 1869 telegraph

cover the word telephone as telephone was

not invented when these acts were passed

contd

• The intention of the legislature assimilates two

concepts

Concept of Meaning ( Literal)

Concept of Purpose & Object ( Purposive)

The process of construction combines both literal &

purposive approaches

Legislative intent to be determined taking the true or

legal meaning of the words in the light of purpose,

object, mischief which it intends to curb and provide

remedy and benefits which it accords.

contd

• Acc to Black Stone the most fair & rational

method for interpreting a statute to explore the

intention of the legislature through the most

natural and probable signs which are “either

words, the subject matter, the effects and

consequence or the spirit and reason of the law”

• A bare mechanical interpretation of wordes will

devoid the concept of purpose

• Krishna Iyer J, “to be literal in meaning is to see

the skin and missing the soul”

Contd..

• The law is a pragmatic instrument of social order and

an interpretative effort must be imbued with the

statutory purpose.

• A construction that would promote the purpose or

object of an Act, even if not expressed, is to be

preferred. “There is no possibility of mistaking

midnight for noon; but at what precise moment

twilight becomes darkness is hard to determine.” (Jane

Straford Boyse v. John T. Rassborough,.

• Thus, the courts, although conscious of such a dividing

line,, do not attempt to draw it for reasons of practical

impossibility; however, sometimes, attempts it after

laying down a working line; howsoever pragmatic, it

may or may not be.

contd

• There is a marginal area in which the courts

mould or creatively interpret legislation and

thus finish or refine legislation which comes to

them in a state requiring varying degrees of

refinement.

• Since, interpretation always implies a degree

of discretion and choice, creativity, a degree

which is especially high in certain areas such

as constitutional adjudication.

Contd..

• Textualism versus Purposivisim

• When Text is not clear Purpose should prevail

• The intention of legislature need to be looked

in in the light of purpose when the text gives

different meanings.

• Example Wife under section 125 Cr.P.C

2.Statute must be read as a whole in its Context

(“EX VISCERIBUS ACTUS”)

• This is the second important basic principle of

interpretation

• When question arises as the meaning of certain

provision, it must be read in its context (circumstances)

• It is legitimate to understand the provision in the light

of the context in which the statute is being applied

• Legislature has the habit of using same word or phrase

in different places in the same statute or other similar

statutes

Contd..

• The context means

the statute as whole,

the previous state of law,

other statutes in pari materia,

the general scope of the statute and

the mischief that it was intended to remedy

Contd.

• A well established rule that the intention of the

statute must be found by reading the statute as a

whole.

• Viscount Simonds, “it is an elementary rule”

• Lord Somervell of Harrow, “compelling rule”

• BK Mukherjee J “settled rule”

• Lord Davey, every clause of the statute must be

construed with reference to context and other

clauses of the Act, so as to make a consistent

enactment of the whole statute or series of

statutes relating to the subject matter.

contd

• Every clause needs to be construed with reference to

the context and other clauses of the Act, to make a

consistent enactment of the whole statute or series

of statutes relating to the subject-matter.

• Reference to the Context - means

Always and not merely when ambiguity arises

It is an elementary principle, that the words of a

statute should be construed in the context of the

scheme of the statute as a whole

Controversial provision should be read in the context

of statute as a whole

• It is the most natural and genuine

exposition of a statute.

• To ascertain the meaning of a clause the

court must look at the whole statute, i.e

what it precedes, what it succeeds, and not

merely at the clause itself

• The conclusion that the language is plain or

ambiguous can be arived only by studying he

statute as a whole

contd

• Sinha CJI, “the court must ascertain the

intention of the legislature by directing its

attention not merely to the clauses to be

construed but to the entire statute, it must

compare the clause with other parts of the

law, and the setting in which the clause to e

interpreted occurs”

• The rule is of general application as even the

plainest terms may be controlled by the

context

contd

• It is conceivable as Lord Watson said, “that the

legislature while enacting one clause in plain terms,

might introduce into same statue or other

enactments which to some extent qualify or

neutralize its effect”

• i.e same word used in different sections of same

statute or even used at different palces in same

clause or section of a statute may bear different

meanings ( Ex: Civil services of a state not to include

HC or Subordinate Court Staff in Art 371-D though

same word includes them in Art 311 CJ AP v.

Dikshitulu)

contd

• How far and to what extent each part of a

statute influences the other part would be

different in each case

• AG v HRH Prince Augustus, House of Lords

allowed Attorney General to refer to the

Preamble of the Statute. Lord Viscount

Simmonds, “ I conceive it as my right and duty

to examine every word in the statute in its

context, and I use context in widest sense..its

preamble…”

contd

• Sir John Nichol, “the key to opening of every law is

the reason and spirit of the law- it is the animus

imponetus the intention of the legislature expressed

in the law itself taken as a whole.”

• Hence to arrive at the true meaning of any provision

or phrase, it should not viewed detached from the

context”

• High Court of Australia, the modern approach to

statutory interpretation insists, Context must be

considered at the first stage not at later stages when

ambiguity arises and in its widest sense.”

Some case law

• OP Sigla v Union of India (1984, AIR SC 1595)

• Rule 7 of the Delhi Higher Judicial Service Rules, 1970 -

recruitment

by promotion and by direct recruitment.

• Proviso - Provided that not more than 1/3rd of the posts in the

service shall be held by direct recruits

• Ceiling or Quota?

Rule 8 - seniority of direct recruits vis-a-vis promotees shall

be determined in the order of rotation of vacancies based on the

quotas of vacancies reserved for both categories by rule 7

• Held - having regard to rule 8 the true intendment of the

proviso to rule 7 is that 1/3rd of the substantive posts must be

reserved for direct recruits.

contd

• Attar Singh v Inderkumar (AIR 1967 SC 773)

• S. 13(a)(ii) of the Punjab Rent Restriction Act, 1949,

enables a landlord to obtain possession in the case of

rented land if-

• (a) he requires it for his own use;

• (b) he is not occupying in the urban area for the purpose

of his business any other such rented land; and

• (c) he has not vacated such rented land without

sufficient cause

• “for his own use” – ‘whatever is the nature of use’ or

‘his own business use?’

Contd..

• SC held: “his own use meant his own business use”

• Observed: All the three clauses were to be read

together and clause (a) was restricted to business

use as were clauses (b) and (c). If this restricted

meaning were not given to the words "for his own

use" in clause (a) the later two clauses would

become inapplicable.

• D Sanjeevayya v Election Tribunal (AIR 1967 SC 1211)

Sec 150 of Representation of People Act, 1951 and

Part III of the Act should be read together

Contd ..

• MCH v PN Murthy (AIR 1987 SC 92)

“buildings and lands vested in the Corporation” –

exempted from tax sec 202 – sec 204 tax shall be levied

from the occupier of he holds premises directly from the

crpn..- question allotters under Hire Purchase agreement

whether to pay or not ..held, property vested both in

title and possession alone exempted..both secs to be

read together

S Gopal Reddy v State of AP AIR 1996 SC 2184

Dowry Prohibition Act, 1961 prohibits both actual

receiveing and demand for dowry..held, text and context

should be read together to find out the object of the Act

contd

• Poaptlal Shah v State of Madras (AIR 1953 SC 274)

BK Mukherjee J, “It is a settled rule of construction that to

ascertain the legislative intent all the constituent parts

of a statute are to be taken together, each word phrase,

sentence is to be considered in the light of the object

and purpose of the Act”

SR Das J, “The meaning of words take colour from the

context in which they appear” “When context makes

the meaning clear it becomes unnecessary for and

select a particular meaning from the diverse meanings a

word is capable of according to lexicographers”

(Mangoo Singh v Election Tribunal AIR 1957 SC 871)

Contd..

• The rule that the statute has to be read as a

whole in its context is of general application,

• The practical utility of the rule is more visible

in constriction of general words and in

resolving in consistencies by recourse to

harmonious construction

3. Statute must be Construed to make it

Effective & Workable

• The Courts must strongly lean against a construction

which reduces the statue to a futility.

• A statute must be construed so as to make it

effective and workable.

• Ut res magis valeat quam pereat

• Presumption in favour of constitutionality of the

statute always to uphold the legislative competence

to enact laws

• No statute shall be declared as void for sheer

vagueness.

•Lord Denning “When a statute has some meaning even though

it is obscure, or several meanings, even though it is little to

choose between them, the courts have to

•say what meaning the statute is to bear, rather than rejecting it

as a nullity”

•The Courts there fore shall not reject the construction which

will defeat the plain intention of the legislature even though

there is inexactitude in the language used

•What ever the meaning the statute has, the same is to be

adapted rather than rejecting it

•Duty of the Court to make statute operative

Contd .

• As far as possible all the words used in the statute must be

given meaning

• Not to be expected that the legislature used unnecessary

words

• It is sensible to presume that the same has not been said

earlier

• Viscount Simmons, “ if the choice is between two

interpretations, the narrower of which would fail to

achieve the manifest purpose of the legislation and avoid

the construction which render the statute to futility.

• The courts may complain that the enactment is mind twisting or

enigma, yet can’t concede that no meaning can be given to it.

contd

• Holmes J, “ It is not adequate discharge of duty

for courts to say, we see what you are driving

at, but you have not said it, therefore shall go

on as before”

• Lord Dunedin, “ it is our duty to make what we

can of statutes knowing that they are meant to

be operative and not inept and nothing short of

impossibility should in my judgment to allow a

judge to declare a statute unworkable”

contd

• CIT v Teja Singh AIR 1959 SC 352

Section 18-A(9) of IT Act, 1922 Notice under sec22(1) , 22(2)

ITO, Mangalore v Damodar Bhat (AIR 1969 SC 408)

The IT Act, 1961 section 297(2) (j) recovery of arrears assessed

under old Act can it be done in new Act

Corporation of Calcutta v Liberty Cinema AIR 1965 SC 1107

Fee should be treated as Tax so as to make the sec 548 workable and

effective

M Pentaih v Veermallappa Muddala AIR 1961 SC 1107

Hyderabad District Municipalities Act, 1956 – sec 320 – sec 16(1)

was held inapplicable to the first election but applicable to subsequent

elections

Udayan Chinubhai v RC Bali (AIR 1977 SC 2319)

Sec 12 of Limitation Act, “ time to compute the limitation shall not be

excluded in computing the period of limitation and not it shall not be

excluded in computing the time requisite for obtaining a copy

4. If Meaning is Plain Effect Must be given to it

irrespective of Consequences

• This is the last of the Basic Principle

• When the words of a statute are clear, plain or

unambiguous, i.e., they are reasonably susceptible

to only one meaning, give effect to that meaning

irrespective of consequences

• Lord Viscount Simonds “…in construing enacted

words we are not concerned with the policy involved

or with the results, injurious or otherwise, which

may follow from giving effect to the language used”

Justice Gajendragadkar

“If the words used are capable of one construction only then

it would not be open to the courts to adopt any other

hypothetical construction on the ground that such

construction is more consistent with the alleged object and

policy of the Act”

SR Das J

“Hardship or inconvenience cannot alter the meaning of the

language employed by the legislature if that meaning is

clear on the face of the statute”

CJ Tindal, “ if the words are themselves precise and

unambiguous then no more necessary to expound them in

their natural and ordinary sense. They themselves declare

the intention of the legislature” ..

i.e when the words are plain &unambiguous and admits

only meaning no question of construction arises. For the

Act speaks for itself.

Contd..

• Results of the construction will not be matter for the

court, even if it is strange, surprising, unreasonable,

unjust or oppressive

• CIT v Keshabchandra Mondal AIR 1950 SC 265

Returns of the Income to be signed an illiterate by the

pen of his son as bakalam

Pakala Narayanaswamy v Emperor AIR 1939 PC 47

sec 162 Cr.P.C “Any Person” includes who may

thereafter be an accused. “when the meaning of the

words is plain it is not the duty of the courts to busy

themselves with supposed intention” (Lord Atkin)

Contd..

. Ramanjay Singh v Bajinath Singh AIR 1954 SC 752

123(7) RP Act, 1951- persons employed by the father and

paid by him, who assisted the son in his election - in

relation to the son are they mere volunteers or

employed?

Argued that its violative of spirit of election law to call them

volunteers?

SR Das J observed:

• "The spirit of the law may well be an elusive and unsafe

guide and the supposed spirit can certainly not be given

effect to in opposition to the plain language of the

sections of the Act”

Contd..

• The rule applies to fiscal and penal statutes.

• If the person to be taxed comes within the letter of the law he

must be taxed..however hardship may appear to the judicial

minds

• MV Joshi v MU Shimpi AIR 1961 SC 1498

11, Prevention of Food Adulteration Rules, 1955 – sale of

butter below prescribed standard was an offense - butter was

defined to mean 'the product prepared exclusively from milk

or cream’ – appellant was held guilty of selling butter below

standard.

Contended in appeal by the appellant that (i)the butter was

made from curd and not from milk, (ii)no foreign article was

added to make it adulterated, (iii)strict construction rule of

penal statute be applied, (iv) adopt the construction

favourable to the subject. Held: appellant was guilty

Justice Subbarao:

“But these rules do not in any way affect the fundamental

principle of interpretation, namely, that the primary test is—the

language employed in the Act and when the words are clear and

plain the court is bound to accept the expressed intention of the

legislature”

CSD Swamy v State ..AIR 1960, SC 7

Sec 5(3) Prevention of Corruption Act, 1947 – rule of evidence –

presumption of guilt in certain cases..- departure from the

normal rule of criminal procedure -

Illachi Devi v Jain Society Protection of Orphans AIR 2003 SC

3397

Sec 233 and 236 Indian Succession Act, - prohibits grant of

probate or letters of Administration “to any association of

persons unless it is a company..” – Plain rule applied and held it

cannot be issued to the society registered under Societies

Registration Act

Guiding Principles of Interpretation

• 1. Language of the Statute should be read as it is

• 2. The Rule of Literal Construction

• 3. Regard to Subject and Object of the Statute

• 4. Regard to the Consequences of Construction

Language of the Statute should be read as it is

• Avoiding addition and Substitution of Words

• Casus Omissus

• Avoiding Rejection of Words

• Departure from the rule

- Additon of words when permissible

- Rejection of words when permissible

- Treating words or provisions as superfluous

Avoiding addition and substitution of words

• Intention of the Legislature primarily to be

gathered from the language used

• Attention to be given on what has been said

and what has not been said

• Any construction which requires for its

support addition or substitution or rejection of

words to be avoided

•

contd

• Privy Council in Crawford v Spooner,” WE cannot

aid the Legislature’s Defective phrasing of an Act,

we cannot add or mend by construction make up

the deficiencies”

• Should not be done

• It is contrary to the rule to read words into the Act

unless it is absolutely necessary to do so

• It is wrong and dangerous to substitute the words

• The courts cannot reframe the Act for the very

reason that it has no powers to legislate

Contd..

• British India Gen Insurance Co v Capt Itbar Singh

held, Sec 96(2) of MV Act 1939 is exhaustive by itself of

defenses open for an insurer the court refused to add the

word ‘also” after the words “ on any of the following words”

The court further held, “ the rule do not permit us to do so

unless the section as it stands is meaningless or doubtful

meaning”

Ramnarayan v State of Bombay ( AIR 1950 SC 459)

Held, Art 31-A(i)(a) of Constitution in holding that “exti

guishment or modification” of any right is a distinct conept

from the acquisition of any state or rights there in, rejected

the argument such ext. and mod. Should apply only in the

process of acquisition of the state

Contd..

• KM Vishwanath Pilai v KM S Pillai (AIR1969 SC 493)

Sec. 42(1) MV Act 1939 which enacts that “No Owner

of transport vehicle shall use or permit the use of the

vehicle in any public place save in accordance with

the conditions of the permit granted or

countersigned”, court held no justification for reading

the words “to him” after the words “permit granted”

Said, the section did not make it necessary that the

owner of the vehicle himself should obtain permit ..

Casus Omissus

• Term casus omissus means “cases of omission”

• Omission in a statute cannot be supplied by

construction.

• A matter which should have been provided but

actually has not been provided in a statute cannot be

supplied by the courts, as to do so will be legislation

and not construction.

• But there is no presumption that a casus

omissus exists and language permitting the court

should avoid creating a casus omissus where there is

none.

• Courts can interpret the law not legislate

(Hansraj Gupta v. DMET Co. Ltd. AIR 1933 P.C. 63)

Contd..

• A casus omissus cannot be supplied by the court by

judicial interpretative process except in the case of

clear necessity and when reason for it is found in the

four corners of the statute itself.

• The language employed in the statute is the

determinative factor of the legislative intent. The first

and primary rule of the construction is that the

intention of the legislature must be found in the

words used by the legislature itself

• The question is not what may be supposed and has

been intended but what has been said

contd

• Francis J. Mc. Coffery observes that it is a rule of statutory

construction that Casus Omissus which means that case

omitted from the language of a statute but within the

general scope of the statute and which appears to have

been omitted due to inadvertence or by overlook cannot

be supplied by the court.

• S.P. Gupta v. President of India AIR 1982 SC 149 the

Supreme Court held that when the language of a statute is

clear and unambiguous - no room for application of the

doctrine of Casus Omissus or for any external aid in such,

the words used by the statute speak for themselves and it

is not the function of the court to add words or expression

merely to suit what court thinks is the supposed intention

of the legislature.

Contd..

• Raghunath Rai Bareja v. PNB (2007) 2 SCC 230 , SC

observed that even if there is defect or omission in

the words used by the Legislature, the Court cannot

correct or make up the deficiencies especially when

literal reading thereof produces an intelligible result

• Ramesh Mehta v. Sanwal Chand Siinghvi AIR 2004 SC

2258. The Supreme Court observed that although

court cannot supply to casus omissus, it is equally

clear that it should not interpret a statute so as

to create a casus omissus when there is really

none.

contd

• Hiradevi v. Dist Board, Shahjahanpur AIR 1952 SC 362

Section 71 and Section 90 of the U.P. District Board Act,

1922 and the Amendment Act 1933 were in question.

Section 71 provided that a Board may dismiss its

Secretary by special resolution, which was amended in

1933 and made the dismissal to take effect after the

expiry of period of appeal or decision of appeal.

However, the corresponding Section 90 pending

enquiry or till sanction is obtained for dismissal in the

old Act which provided for suspension of the Secretary

pending enquiry was not amended. Therefore, Section

71 was amended but not Section 90.

Contd..

• Justice Bhagwati in this case observed that, it was

unfortunate that when legislature came to amend

Section 71, it forgot to amend Section 90 in

conformity with amendment of Section 71. But

this lacuna cannot be supplied by any liberal

construction. No doubt, it is the duty of court to

try and harmonize the various provisions of an Act

passed by the Legislature. But, it is certainly not

the duty of the court to stretch the word used by

Legislature to fill in gaps or omissions in the

provisions of an Act.

Contd..

• Gladstone v. Bower, - Agricultural Holdings Act, 1948,

section 23 applied tenancy for year to year – sec. 2

less than one year, sec 3 term for two years more..no

provision for 18 months, held court cant fill the gaps

• Basavantappa v. Gangadhar Narayana Dharwadkar

(1986) 4 SCC 273 P.K. Unni v. Nirmala Industries AIR

1990 SC 933 Dadi Jagannadam v. Jammulu Ramulu

AIR 2001 SC 2699 These cases relate to construction

of Rule 89 of Order 21 of CPC after the Amendment

of Article 127 of the Limitation Act, 1963.

Contd..

• Rule 89 of Order 21 of CPC provides that if any person

claiming an interest in the property sold in execution of a

decree applies to have the execution sale aside and deposits

within 30 days from the date of sale, 5% of the sale money for

payment to the purchaser and the amount payable to the

decree holder, ‘the court shall make an order setting aside the

sale.’

• The period of limitation for applying under Rule 89 was also

30 days which was enlarged to 60 days by way of an

amendment in the Limitation Act.

• The Parliament however failed to make corresponding

amendment in the Rule 89 to enlarge the period for making

deposit

Contd..

• The two judge bench in Dharwadkar held that

it is implied that the period in both the cases

is enlarged to 60 days

• Which was not accepted in Nirma Industries

Case

• Later in Ramulu’s case Nirma Case was

overruled and the Supreme Court held that

the court must try to harmonise the

conflicting provisions.

contd

• Denning LJ, “When a defect appears a judge cannot simply

fold his hands and blame draftsman. He must set to work on

the constructive task of finding the intention of parliament

and then he must supplement the written words so as to

give force and life to the intention of the legislature”

• The intention of legislature can be better found by filling up

the gaps

• Criticism….

• Denning’s view was approved by SC in Bangalore Water

Supply v. Rajappa. While dealing with the definition of

‘Industry’ under ID Act, 1947, the definition was ambiguous

and so general some judicial heroics were required. CJ Beig

contd

• Karnataka State v UOI AIR 1978 SC 68.

Sec. 35(2) FERA 1973, 104(2) Customs Act, 1962 – every

arrested person to be presented before a Magistrate within

24 hours – no provision empowering authorize magistrate

further detention. SC held, sec 167(2) of Cr.PC applies to FERA

and Customs Act, otherwise the provisions become useless.

• Boddu Narayanamma v Sri Venkateswara Aluminum Co

The AP Building (Lease Rent & Eviction) Control Act, 1960

Buildings categories into residential and non

residential..what about the building which are given on

composite lease..held, has to be categorized according to the

nature accommodation and dominant purpose of the lease

• Omissions not to be considered as

defect which can be cured by supply of

words.

• Cannot be supplied except in the case

of clear necessity and when reason for it

is found in the four corners of the

statute itself.

Avoiding the Rejection of Words

• Not permissible to add words or fill gap or lacuna, on

other hand effort should be made to give meaning

each and every word

• “It is not a sound construction to brush aside the

words” – J Patanjali Shashtri

• Incumbent on the part of the court to avoid a

construction which devoid of any meaning or

application

• Presumption that legislature inserted every provision

or word for a purpose and is not deemed to waste its

words

contd

• Any construction which attributes redundancy

to the legislature will not be accepted except in

compelling situations

• Hill v Williams Hil (Park Lane) ltd.. Gaming Act,

1845..sec 18 ‘All the contracts or agreements by

way of gaming or wagering shall be null and

void and no suit shall be brought or maintained

for recovery any sum or thing which is alleged

to be won on ay wager’ question a separate

agreement to pay is enforceable..held, no

Contd..

• State v Ali Gulshan..sec. 6(4) Bombay Land Requisition

Act, 1948 ‘requisition of land for the purpose of state or

any public purpose’ question any other public purpose

restricted to purpose of state..held no

• Balwant Kaur v Chararan Singh. Hindu Adoption and

Maintenance Act, 1956 – sec. 19 ‘maintenance to the

Hindu wife from the estate of her husband or her father

and mother’ held, section personal right against father

and mother ‘estate of’ before the words ‘her husband’

not to be read before the words ’her father and

mother’ otherwise section 22(2) becomes otiose.

Exceptions – Departure from the Rule

• As already stated not permissible to read words into

the statute

• But in discharging its interpretative function the

court can correct obvious legislative errors & in

suitable cases will add, or omit or substitute the

words

• Three things the court must be sure :-

1. the intended purpose of the stature in wuestion

2. By inadvertence the P’ment failed to give effect

3. The error noticed

Addition of words when permissible

• Words may be read into the Act to give effect to the

intention of the legislature which is apparent form the Act

• Where it appears the words have been accidentally

omitted or if the constriction adapted deprives the

existing provision all the meaning, it is permissible to add

words

• Departure from the rule is to avoid any statute becoming

meaningless.

• But before adding words it must be made sure that even

Legislature would have added the words had they noticed

the error

Contd..

• Siraj ul Haq v Sunni Central Board of Wakf UP

sec. 5(2), ‘Mutawalli of a wakf or any person

interested in a Wakf’….held, any person

should be understood as, “any person

interested in what is held to be a wakf

Gajendragadkar J, “ where literal meaning of the

words used in the statute defeat the main

object by making it meaningless or ineffective,

it is legitimate to adopt liberal construction to

give meaning to all the statutes

Contd..

• State Bank of Travancore v Mohammad

Sec. 4(1) of Kerala Agriculturists Debt Relief Act, 1970

“any debt due before the commencement of this Act to any

Banking Company..”..the SC construed them as, “any debt

due at and before the commencement of this Act”

Chandrachud CJ, “..that is the only rational manner by which

we can give meaning and content to it to further the

object of the Act”

Union Bank v Seppo Rally

Sec. 17 C P Act 1986 – State Commission – Territorial

Jurisdiction, held, as per sec. 11 Jurisdiction of Dist.

Forum

Rejection of words when permissible

• Words introduced due to inadvertence or unskilfulness

of the legislature can be rejected to make the statute

effective and workable.

• Since the courts not to reduce the statute to a futility, it

is permissible to reject the surplus words

• Salmon v Duncombe,

“Any natural born subject of Great Britain and Ireland

resident within this district may exercise all the rights of

disposal property by will ‘as if such natural born subject

resided in England….intention was clear but due to last

nine words, the provision is meaningless, held, that the

last nine words be rejected

Treating the words as superfluous

• Legislature sometimes use superfluous words –

tautological expression due to ignorance of law

or sometimes as a matter of abundant caution –

not uncommon..

• To find special exemptions which are already

covered under general exemptions

• A provision which owes its origin to a confusion

of ideas or misunderstanding of law or abundant

caution the court considers them as superfluous

2. The Rule of Literal Construction

Natural & Grammatical Meaning

• By the literal rule, words in a statute must be

given their plain, ordinary or literal meaning.

• The objective of the court is to discover the

intention of Parliament as expressed in the

words used.

• This approach will be used even if it produces

absurdity or hardship, in which case the remedy

is for Parliament to pass an amending statute.

Contd..

• One of the leading statements of the literal rule was

made by Tindal CJ in the Sussex Peerage Case (1844)

11 Cl&Fin 85 “… the only rule for the construction of

Acts of Parliament is, that they should be construed

according to the intent of the Parliament which

passed the Act. If the words of the statute are in

themselves precise and unambiguous, then no more

can be necessary than to expound those words in

their natural and ordinary sense. The words

themselves alone do, in such case, best declare the

intention of the lawgiver.”

Lord Esof in

R v Judge of the City [1892] 1 QB 273 said:

•“If the words of an Act are clear then you must follow

them even though they lead to a manifest absurdity.

The court has nothing to do with the question whether

the legislature has committed an absurdity.

Facts

• In the case Mr C, the Claimant, was injured in a car.

• The Defendant’s insurance only covered him under the

Road Traffic Act 1988 for the use of his car ‘on any highway

and any other road to which the public has access’. Issue

• The question for the court to determine, therefore, was

whether the multi-storey car park was a road?

Held

•The HL held that the car park was not a road

because a road provides for cars to move along

it to a destination.

•Therefore, the insurance company was not

liable to pay out on the driver’s policy because

the claimant had not been injured due to the

use of the car on a “road”.

Inland Revenue Commissioners v Hinchy (1960)

Tax penalty case

Issue

•Concerned the construction of s.25 (3) of the Income

Tax Act 1952

•The Act stated that anyone convicted should be subject

to a fixed penalty and triple the tax which he ought to

have been charged under the Act

•The Court had to decide whether the amount should

be based on the whole amount that was liable under the

statute or just the unpaid amount

•The Court decided that on the literal rule he was liable

to pay the whole amount, even though this was a harsh

decision

Whiteley v Chappell (1868) LR 4 QB 147

aka Dead person case

• Facts:

• Defendant was arrested for impersonating a dead

person in order to cast an extra vote Provision:

• A statute aimed at preventing election rigging

made it an offence to impersonate “…any person

entitled to vote” at an election. Issue:

• Was he guilty or not guilty of casting an extra vote?

• Held, He was found not guilty as dead people are

clearly not entitled to vote!

London and North Eastern Railway v Berriman [1946]

AC 278

• Facts

• A railway worker was knocked down & killed by a train

while oiling parts of the line. His wife was claimed

compensation for his death. Provision

• The relevant statute said that compensation was available

for workers who were ‘..killed whilst repairing the line…’

Issue

• Whether the widow is entitled for the compensation.

• The court held that in the ordinary sense of the word,

‘repairing’ did not include oiling as this was merely

maintenance

Maqbool Hussain v. St of Bom.(AIR 1953 SC325)

aka Gold Confiscated case

• Facts: A person was tried and penalised under Sea

Customs Authority Act, 1878 for smuggling Gold.

• He was later tried under FERA in the Court

• Question can he be tried again for same offence and

violation of Art 20(2) of Constitution

• Held, Sea Customs is not a court and therefore can

be tried again by FERA

Motipur Zamindary Company Pvt. Ltd. V. St of Bihar

(AIR 1962 SC 660)

Facts • Green vegetable are exempted of the sales tax

within Bihar Sales Tax Act, 1947 Issue

• Whether sugarcane fall within the term green

vegetable?

Held: • That sugar cane was not a green vegetable and

was not exempted under the notification.

• The word "vegetables" in taxing statutes was to be

understood as in common parlance i.e. denoting class

of vegetables which were grown in a kitchen garden or

in a farm and were used for the table.

• The dictionaries defined sugar cane as a "grass."

Ramavtar Budhaiprasad v. Assistant Sales Tax Officer.

The Supreme court was faced with a question with the

meaning of “vegetable”, as it had occurred in the C.P &

Berar Sales Tax Act, 1947

whether the word vegetables included betel leaves or

not.

The Supreme Court held that “being a word of everyday

use it must be construed in its popular sense”.62 It was

therefore held that betel leaves were excluded from its

purview.

The Literal Rule, also known as the Plain-Meaning rule,

is a type of statutory construction, which dictates that

statutes are to be interpreted using the ordinary

meaning of the language of the statute unless a statute

explicitly defines some of its terms otherwise.

In other words, the law is to be read word for word and

should not divert from its true meaning.

The Literal Rule means that the words need to be

interpreted in the strict ordinary meaning and the

scope of words should not be considered more than its

ordinary meaning. The words are to be understood in

their ordinary and natural meaning unless the object of

the statute suggests otherwise

The words of a statute are first understood in their natural,

ordinary or popular sense and phrases and sentences are

construed according to their grammatical meaning, unless

that leads to some absurdity or unless there is something in

the context, or in the object of the statute to suggest the

contrary.

"The true way", according to Lord Brougham is, "to take

the words as the Legislature have given them, and to take

the meaning which the words given naturally imply, unless

where the construction of those words is, either by the

preamble or by the context of the words in question,

controlled or altered

Contd..

• Lord Atkinson: In the construction of statutes, their

words must be interpreted in their ordinary grammatical

sense unless there be something in the context, or in the

object of the statute in which they occur or in the

circumstances in which they are used, to show that they

were used in a special sense different from their ordinary

grammatical sense.

• Basis of this principle, the words has to be interpreted

according to the rules of grammar to ascertain the

intention of the legislature

• Safe rule – if language is plain effect to be given

irrespective of the consequences.

Contd..

• Souhthendran v Immiration Appeal Tribunal - section

14(1) of the Immigration Act, 1971, which provides

that "a person who has a limited leave under this

Act to enter or remain in the United Kingdom may

appeal to an adjudicator against any variation of the

leave or against any refusal to vary it".

"a person who has a limited leave" were construed

not to include a person "who has had" such limited

leave and it was held that the section applied only to

a person who at the time he lodged his appeal was

lawfully in the United Kingdom that is in whose case

leave had not expired at the time of lodgment of

appeal.

Contd..

• SC dealing with Order 21 Rule 16 of CPC held actual transfer

of decree means assignment in writing after decree is passed

• SR Das J, referring to the rule under discussion said: The

cardinal rule of construction of statutes is to read the statutes

literally, that is, by giving to the words their ordinary, natural

and grammatical meaning. If, however, such a reading leads to

absurdity and the words are susceptible of another meaning,

the Court may adopt the same. But if no such alternative

construction is possible, the court must adopt the ordinary

rule of literal interpretation. In the present case the literal

construction leads to no apparent absurdity and therefore,

there can be no compelling reason for departing from that

golden rule of construction

Contd..

• SA Venkatram v State – held Sec 6 of Prevention of

Corruption Act, 1947, that sanction is not necessary

for taking cognizance of the offences referred to in

that section if the accused has ceased to be a public

servant on the date when the court is called upon to

take cognizance of the offences. The court rejected

the construction that the words "who is employed—

and is not removable" as they occur in clauses (a)

and (b) of section (1) mean "who was employed—

and was not removable",

To avoid ambiguity, legislatures often include "definitions"

sections within a statute, which explicitly define the most

important terms used in that statute.

The plain meaning rule attempts to guide courts faced with

litigation that turns on the meaning of a term not defined by the

statute, or on that of a word found within a definition itself.

When it is said that words are to be understood first in their

natural ordinary and popular sense, means that words must be

ascribed their natural, ordinary or popular meaning which they

have in relation to the subject matter with reference to which

and the context in which they have been used in the Statute.

In the statement of the rule, the epithets ‘natural, “ordinary”,

“literal”, “grammatical” and “popular” are employed almost

interchangeably to convey the same idea. The word ‘primary’ is

used to convey the same idea

contd

• The natural or ordinary meaning of the word should be

understood in its context as sometimes the words may have a

secondary meaning ( different meanings)

• Ex: Coal..SC held under Sales Tax Act, include charcoal not just

coal derived from mineral, but under Colliery Control Order

coal is confined only to mineral

• Popular meaning to be derived according to how the people

deal with the subject understood them

• Same applied in determining Paddy & Rice and Textiles to

cover cotton woolen clothes.

• FRO v Kushboo Enterprises – held, ‘wood oil’ from forest

produce not to include Sandalwood oil.

Contd..

• Exact Meaning preferred to Loose meaning

presumption that words are used exactly not

loosely.

word ’contiguous’ interpreted to its exact

meaning as ‘touching’ not as ‘neighboring’ the

loose meaning.

similarly PC held ‘adjoining’ as conterminous’

but not as near

Contd..

• Technical Words in technical sense

Special Meaning in trade, business :

Natural & ordinary meaning of the words to be understood in

a legislation relating to a particular trade, business, profession

etc..

• Such a special meaning is called the technical meaning to

distinguish it from the more common meaning that the word

may have

• As pointed by Lord Esher MR: If the Act is one passed with

reference to a particular trade, business or transaction and

words are used which everybody conversant with that trade,

business or transaction knows and understands to have a

particular meaning in it, then the words are to be construed

as having that particular meaning

The power, therefore, given to a Surveyor under section 65 of the

English Highways Act, 1835 to "lop" trees growing near a highway

was construed as conferring the power to cut off the branches but

not to "top", i.e., to cut off the top of the tree.

Legal Words in Legal Sense

On the same principle when words acquire a technical meaning

because of their consistent use by the Legislature in a particular

sense or because of their authoritative construction by superior

courts, they are understood in similar context in subsequent

legislation

3. Regard to Subject & Object – Mischief Rule

• Where there is a doubt about the meaning of the words, they

should be best understood in by harmonizing the subject &

object of the Act

• Hand J, “The courts have declined to be bound by the letter,

when it frustrates the patent purpose of the statute.”

• Courts should adopt an object-oriented approach to avoid the

legislative futility within the permissible interpretative limits

• However, such approach shall not extend to cause violence to

the plain language used inn the statute

• UP Bhoodan Yagna Samithi v Braj Kishore

Up BhoodanYagna Act, 1953 – held, sec 14 ‘landless persons’ – to

mean landless labors – not landless businessmen – object of the

Act was considered

Contd.

• Workmen of Dimakuchi Tea Estate v Mgt

ID Act, 1947 – sec 2(k) ‘Industrial Dispute’ many dispute

between employers & employees or between employees and

workmen or between workmen and workmen ..in connection

with any employment or non employment or terms of

employment or conditions of labour of any person – held, ‘any

person’ – dispute must be real and capable of giving necessary

relief and as the person regarding whom the dispute raised to

have a substantial interest.

• Santa Singh v State – SC held, sec. 235(2) CrPC, 1973, hearing

of accused on the question of sentence and pass according to

law as mandatory to bring in conformity with the modern

trends of penology

Contd..

• Narendra Madivalappa v Manikrao Patil

sec 23 Representation of the People Act, 1951 – inclusion of names

in the electoral roll till the last date of nomination – last date was

interpreted as last hour of nomination on the last date as per sec

33(1) which provides that the nominations can be filed between 11

am to 3 pm.

Bipin Chandra Patel v State – sec 40(1) Gujarath Municipality Act

empowers the authorized to suspend the president or vice president

if they have been detained in a prison during a trial – held, the

section empowers to suspend even if the detention is made during

the investigation of the case not only when detained after the charge

is framed. Keeping the object of the statute to keep the shady

characters away from the administration

When two interpretations possible o the one which supresses the

mischief and advances the remedy to be taken

Contd..

• Same expressions in two different statutes in

similar context may have different meanings

having regard to the object of the enactment

Example: VC Shukla v State – Interlocutory Order

Sec 397 CrPC & sec 11 Special Courts Act

• Summary: the meaning of the words not to be

taken ordinarily in abstract – regard to be to

be given to its setting, subject and object of

the Act

3A - Mischief Rule of Interpretation

• The Mischief Rule means judges can apply in

statutory interpretation in order to discover

Parliament’s intention.

• This rule has often been used to resolve ambiguities

in cases in which the literal rule cannot be applied.

• This rule is so called as ‘mischief rule’ because it

envisages that construction, by which the mischief is

suppressed

• Lord Simonds concedes that the mischief is part of the

context and that he says that other sections of the

statute, the preamble, the existing state of the law and

other statutes in pari materia may be used to throw

light on that mischief.

Mischief Rule contd..

• The mischief rule is applied to find out

what Parliament MEANT.

• It looks for the wrong: the 'mischief' which

the statute is trying to correct

• The rule is based on the Heydon’s Case [1584]

– VERY OLD!

• Also called as Hedon’s Rule

• The rule applies to all the statutes be

beneficial, restrictive, enlarging, penal..etc..

The rule also known as Purposive Construction.

The rule enables consideration of four things

• What was the common law before the passing

of the Act?

• What was the mischief and defect for which

the common law did not provide?

• What remedy the Parliament had resolved and

appointed to cure the “disease of the

Commonwealth”.

• The true reasons for the remedy.

Contd..

• The rule directs the court to adopt such construction

which shall suppress the mischief and advances the

remedy.

• This rule requires the court to look to what the law was

before the statute was passed in order to discover what

gap or mischief the statute was intended to cover.

• This rule gives the court justification for going behind

the actual wording of the statute in order to consider

the problem that the particular statute was aimed at

remedying

• it is limited to using previous common law to determine

what mischief the Act in question was designed to

remedy.

Contd..

• The rule in Heydon’s case followed in England

• Earl of Halsbury, - “it is not only legitimate but highly

convenient to refer both former &later Acts to

ascertain evils which the former Act given rise & later

Act provides remedy”.

• Statutes to be given purposive construction, i.e. to

identify the mischief and suitable construction that

remedies.

• The purposes of the Act and the mischief rule are,

therefore, closely connected, and it is very genuine

to look at the long title, scope and object of the Act

Case laws – Mischief Rule

• Smith v Huges – Street Offences Act, 1959

sec 1(1) – soliciting the customers by prostitutes in a

street is offence – question soliciting from balconies be

considered as in a street – held, yes – the object of the

Act to keep the streets clean and peaceful for

commuters

RMDC v Union of India the definition of ‘prize

competition’ under s 2(d) of the Prize competition act

1955, was held to be inclusive of only those instances

in which no substantive skill is involved.

Thus, those prize competitions in which some skill was

required were exempt from the definition of ‘prize

competition’ under s 2(d) of the Act.

The Supreme Court has applied the Heydon’s Rule in

order to suppress the mischief was intended to be

remedied, as against the literal rule which could have

covered prize competitions where no substantial

degree of skill was required for success.

Corkery v Carpenter 1951 aka Drunk n Ride case

• Law: S.12 of the Licensing Act 1872 made it an

offence to be drunk in charge of a carriage on the

highway.

• Facts: The defendant was riding his bicycle whilst

under the influence of alcohol. Apply the mischief

rule – what do you think is the mischief? And is the

person guilty?

• Held: The court applied the mischief rule holding that

a riding a bicycle is a carriage. This was within the

mischief of the Act as the defendant represented a

danger to himself and other road users.

Contd..

• Bengal Immunity Co’ case – SC applying the rule held,

Art 286 as one to cure the mischief of multiple

taxation and to preserve the free flow of the inter

state trade in Union of India without any provincial

barrier.

• Alamgir v State – sec. 498 IPC - Whoever takes or

entices away any woman who is and whom he knows

or has reason to believe to be the wife of any other

man, from that man, ….- question – if taking away

with the consent of the woman offence – applying

the rule the SC held, against the consent of the

husband as offence.

Contd..

CIT v. Smt. Sodra Devi, - Section 16(3) of the Indian

Income-tax Act, - question- whether the word

'individual ' in s. 16(3) of the 'Indian Income-tax Act,

1922, as amended by Act IV of 1937, includes a female

and whether the income of minor sons from a

partnership, to the benefits of which they were

admitted, was liable to be included in computing the

total income of the mother who was a member of the

partnership.

held, The word 'individual' occurring in s. 16(3) of the

Indian Income-tax Act, as amended by Act IV Of 1937,

means only a male and does not include a female.

Contd..

• The rule attains importance in construing the

statutes like Prevention of Food Adulteration

Act, 1947, Dowry Prohibition Act, 1986 etc..

• However, the rule is applicable only when the

words are ambiguous and are reasonably

capable of more than one meaning.

• Whether the language is ambiguous or not,

be understood by looking at the context of the

Act

4 Regard to Consequences – Golden Rule

• If the language is capable of bearing more than one

construction, regard must be given to the consequences

• Construction that gives undesired results, which he

statute doesn’t intend, to be rejected

• Hardship, Inconvenience, Injustice, Absurdity &

Anomaly to be avoided.

• This is called Golden Rule of interpretation, a

modification of literal rule of interpretations

• Rule no application if the words are susceptible to only

one meaning

Golden Rule of Interpretation

• Hardship, Inconvenience, Injustice, Absurdity

& Anomaly to be avoided.

• Courts to adopt that interpretation,

reasonable and sensible.

• Presumption that legislature not used the

word which offends the sense of justice

Contd..

• If the plain meaning of the word – is ambiguous,

vague or misleading or – if a strict literal

interpretation would result in absurd results

• then the court may deviate from the literal meaning

to avoid such an absurdity.

• This is also known as the Golden Rule of

interpretation.

• It is the modification of the literal rule of

interpretation - tries to avoid anomalous and absurd

consequences from arising from

literal interpretation.In view of the same, the

grammatical meaning of such words is usually

modified.

contd

• Lord Wensleydale in Grey v Pearson (1857)

Propounded this rule –

• “… the grammatical and ordinary sense of the words

is to be adhered to, unless that would lead to some

absurdity, or some repugnance or inconsistency with

the rest of the instrument, in which case the

grammatical and ordinary sense of the words may be

modified, so as to avoid that absurdity and

inconsistency, but no farther.”

Contd..

• It is the modification of the literal rule of

interpretation.

• The literal rule emphasizes on the literal meaning

of legal words or words used in the legal context

which may often lead to ambiguity and absurdity.

• Justice Parke “It is a very useful rule in the construction of

a statute to adhere to the ordinary meaning of the words

used, and to the grammatical construction, unless that is at

variance with the intention of the legislature to be collected

from the statute itself, or leads to any manifest absurdity or

repugnance, in which case the language may be varied or

modified so as to avoid such inconvenience but no further.”

LITERAL GOLDEN RULE

Three Fundamental Rules

• Firstly, the literal rule that, if the meaning of

the section is plain, it is to be applied whatever

the result.

• Secondly, “golden rule” that the words should

be given their ordinary sense unless that would

lead to some absurdity or inconsistency with

the rest of the instrument;

• Thirdly, the general policy of the enactment

and the evil at which it was directed.

Contd..

• For the application of the literal rule, a clear and

unequivocal meaning is essential.

• Jugal Kishore Saraf v. Raw Cotton Co. Ltd.[the

SC held, that the cardinal rule of construction of statutes

is to read the statutes literally, that is by giving to the

words their ordinary, natural and grammatical meaning.

If, however, such a reading leads to absurdity and the

words are susceptible of another meaning, the court may

adopt the same. But when no such alternative

construction is possible, the court must adopt the

ordinary rule of literal interpretation.

cont

• Under the literal interpretation of this sign,

people must never use the lifts, in case

there is a fire.

• However, this would be an absurd result,

as the intention of the person who made

the sign is obviously to prevent people

from using the lifts only if there is currently

a fire nearby.

Contd..

• Applying the golden rule, the court held that

requirement of the section had not been

followed by the driver as he had not stopped

for a reasonable period requiring interested

persons to make necessary inquires from him

about the accident.

• The rule suggests that the consequences &

effects of an in interpretation deserves a lot

more importance since they are clues to the

true meaning of the legislature

Contd..

• UP Bhoodan Yagna Samithi v Braj Kishore

Up BhoodanYagna Act, 1953 – held, sec 14 ‘landless

persons’ – to mean landless labors – not landless

businessmen – object of the Act was considered.

• Thirath Singh v Bachitar Singh – sec 99 RP Act,

1951 – Election Tribunal authorized to name all

the persons guilty of election corrupt practices

provided notice is given to such persons and

examined – question, notice to be given to

parties of the petition too- held, no - - grounds of

reasonableness and justification

Contd..

• Ramji Missar v. State of Bihar[x

- Sec 6 of the Probation of Offenders Act, 1958,

the SC held, crucial date on which the age of the

offender had to be determined is not the date of

offence, but the date on which the sentence is

pronounced by the trial court. An accused who

on the date of offence was below 21 years of

age but on the date on which the judgment

pronounced, if he was above 21 years, he is not

entitled to the benefit of the statute.

Advantages

• This rule prevents absurd results in some cases

containing situations that are completely

unimagined by the law makers.

• It focuses on imparting justice instead of blindly

enforcing the law.

Disadvantages

• The golden rule provides no clear means to test the

existence or extent of an absurdity. It seems to

depend on the result of each individual case.

• This rule tends to let the judiciary overpower the

legislature by applying its own standards of what is

absurd and what it not.

Harmonious Construction

Avoiding Inconsistency & Repugnancy

• Statute must be read as a whole, i.e one

provision should be construed to other

provision in the same Act to make it consistent

• This will avoid the inconsistency & repugnancy

either with a section or with other parts of the

Statute.

• Court tom avoid the Head on Clash between

two sections of same Act & to harmonize

whenever such conflict appears

Contd..

• This is known as Harmonious Construction

• Harmonious construction is a principle of

statutory interpretation, which holds that

when two provisions of a legal text seem to

conflict, they should be interpreted so that

each has a separate effect and neither is

redundant or nullified.

• No assumption that legislature gave from one

hand and taken away by other

Contd..

• The provision of one section cannot be used to defeat

the provision contained in another unless the court,

despite all its effort, is unable to find a way to reconcile

their differences,

(CIT v Hindustan Bulk Carriers (2003)

• Courts must also keep in mind that interpretation that

reduces one provision to a useless number or dead is

not harmonious construction.

• To harmonize is not to destroy any statutory provision

or to render it fruitless.

contd

• When it is impossible to completely reconcile the

differences in contradictory provisions, the courts

must interpret them in such as way so that effect is

given to both the provisions as much as possible.

• The rule applies to sub sections within the provisions

– try to harmonize or give effect to both

• It runs on the premise that Parliament did not make

the provisions in a an enactment to defeat each

other or to make one of them ineffective by giving

only effect to the other/s.

Contd..

• The familiar approach in resolving the conflict – to

find out which of the provision is more general &

which one more specific

• Then to construe the general one to exclude the

specific one

• The question whether general or specific can be

determined with reference to area and extent of

application

Contd..

• Principle explained – Generalia Specialibus non

derogant, Generalia Specialibus derogant

• If a special provision is made on a certain matter, it is

excluded from general provision

• This principle used to resolve conflict between the

provision and the rule in the Act

• When it is impossible to completely reconcile the

differences in contradictory provisions, the courts

must interpret them in such as way so that effect is

given to both the provisions as much as possible.

Contd..

• Venkaramana Devru v State – Conflict between Art

26(b) Indian Constitution Right to manage religious

affairs – Art 25 – Right to worship – sec 3 Madras

Temple Entry Authorisation Act, 1949 – entitling

Harijans to enter temple, held, Right to manage

religious affairs is subject to Right to worship

• MSM Sharma v Krishna Singh (Search Light Case)

Held, Art 19(1) – freedom of speech and expression

subject to Art 194(3) Parliamentary Privileges

• Kehavananda Bharathi Case held, Art 368 power to

amend the constitution is subject to the rule basic

structure cannot be affected

contd

• KM Nanavathi v State – Art 161 Governor Power to

pardon not available during SLP under Art 142

• Sirsilk Ltd. v. Govt. of Andhra Pradesh – held, sec 17 –

Publication of Award under ID Act, 1947 is

mandatory even if the parties entered into a

separate agreement subsequently under sec 18.

• D Sanjeeviah v Election Tribunal held, Power of EC to

hold Bye Election under sec 150 should be read witrh

sections 84 & 98(c)

Contd..

When reconciliation is not possible

• It is a general rule that when reconciliation is not possible

the later provision shall prevail.

• Eastbourne corporation v. Fortes Ltd(1959)

“If two section of an Act of Parliament are in truth

irreconcilable, then prima facie the later will be preferred.”

• However, a better approach has been devised where

hierarchy of provisions is to set.

• Institute of Patent Agents v. Lockwood(1894)

In case of irreconcilable provisions, “you have to determine

which is leading provision, and which is subordinate

provision and which must give way to other.”

You might also like

- Meaning of InterpretationDocument25 pagesMeaning of Interpretationankit vermaNo ratings yet

- Interpretation of Statutes,: Submitted byDocument17 pagesInterpretation of Statutes,: Submitted bySwatiVermaNo ratings yet

- Interpret of StatuteDocument55 pagesInterpret of StatutepankajNo ratings yet

- The Indian Law & A Lawyer in India: TH THDocument7 pagesThe Indian Law & A Lawyer in India: TH THShubham Jain ModiNo ratings yet

- Civil Procedure Code - by Justice NaimuddinDocument635 pagesCivil Procedure Code - by Justice NaimuddinEhsanul KabirNo ratings yet

- LB-6031 Contents Interpretation of Statutes and Principle of Legislation January 2018Document6 pagesLB-6031 Contents Interpretation of Statutes and Principle of Legislation January 2018Arihant RoyNo ratings yet

- External AidsDocument4 pagesExternal AidsShashikantSauravBarnwalNo ratings yet

- Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral AwardsDocument21 pagesEnforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awardsshanthosh ramanNo ratings yet

- Moot ProblemDocument3 pagesMoot ProblemAditya AnandNo ratings yet

- Interpretation of StatutesDocument1 pageInterpretation of StatutesAmir KhanNo ratings yet

- Section 8 of The Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 A Saving BeaconDocument3 pagesSection 8 of The Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 A Saving BeaconPooja MeenaNo ratings yet

- Contract NotesDocument111 pagesContract NotesRiya RoyNo ratings yet

- Internal Aid To ConstructionDocument20 pagesInternal Aid To ConstructionCNLU Batch 2015- 2020No ratings yet

- Chart of Parsi Divorce PDFDocument3 pagesChart of Parsi Divorce PDFJating JamkhandiNo ratings yet

- 4 Internal Aids To InterpretationDocument21 pages4 Internal Aids To InterpretationMILINDSW100% (1)

- The Kenyan Worker and The Law: An Information Booklet On Labour LawDocument32 pagesThe Kenyan Worker and The Law: An Information Booklet On Labour LawsashalwNo ratings yet

- Principles of Interpretation of StatutesDocument60 pagesPrinciples of Interpretation of StatutesLokesh Batra100% (1)

- Strict Construction RuleDocument4 pagesStrict Construction RuleReubenPhilipNo ratings yet

- Interpretaion of StatuesDocument7 pagesInterpretaion of StatuesReshab ChhetriNo ratings yet

- Company LawDocument20 pagesCompany LawRamyaBtNo ratings yet

- General Clauses ActDocument10 pagesGeneral Clauses ActShivam MishraNo ratings yet

- Amendments To The Arbitration and Conciliation ActDocument13 pagesAmendments To The Arbitration and Conciliation ActPrishita Chadha100% (1)

- Arbitration Act 2001 PDFDocument11 pagesArbitration Act 2001 PDFCryptic LollNo ratings yet

- Will PDFDocument14 pagesWill PDFAnadi GuptaNo ratings yet

- The Specific Relief ActDocument14 pagesThe Specific Relief Acthoney DhingraNo ratings yet

- Geneva ConventionDocument6 pagesGeneva Conventionmanuvjohn1989No ratings yet

- Interpretation of StatuesDocument28 pagesInterpretation of StatuesGoldy SharmaNo ratings yet

- Notes of Interpretation of Statute, Class LL.B (TYC) 4 SemesterDocument39 pagesNotes of Interpretation of Statute, Class LL.B (TYC) 4 SemesterGurjot Singh KalraNo ratings yet

- Techniques: Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) / Online Dispute Resolution (ODR)Document15 pagesTechniques: Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) / Online Dispute Resolution (ODR)Kartik BhargavaNo ratings yet

- Law Referencer For Quick RevisionDocument34 pagesLaw Referencer For Quick RevisionNeeraj BhattNo ratings yet

- International ConventionsDocument9 pagesInternational ConventionsChandrika MehtaNo ratings yet

- IPR ConventionsDocument12 pagesIPR Conventionsgirish karuvelilNo ratings yet

- 10 Things About Civil Procedure CodeDocument17 pages10 Things About Civil Procedure Codesubbarao_rayavarapuNo ratings yet

- Conflict of Law NotesDocument11 pagesConflict of Law Notesfarheen haiderNo ratings yet

- Ios Notes PDFDocument64 pagesIos Notes PDFHeena Shaikh100% (1)

- Bail Application Under Section 439 of The Code of Criminal Procedure Code 1973Document4 pagesBail Application Under Section 439 of The Code of Criminal Procedure Code 1973C Govind VenugopalNo ratings yet

- Written Statement - Synopsis - : Meaning - Who May File Written Statement - Time Limit For Filing Written StatementDocument3 pagesWritten Statement - Synopsis - : Meaning - Who May File Written Statement - Time Limit For Filing Written StatementAnjana JoseNo ratings yet

- EvidenceDocument78 pagesEvidenceSanjay SinghNo ratings yet

- 8th Sem Assignment-2Document2 pages8th Sem Assignment-2muhammedswadiqNo ratings yet

- Ipr NotesDocument37 pagesIpr NotesManav BhagatNo ratings yet

- Unit IIDocument29 pagesUnit IIabhiNo ratings yet

- Copyright Study MaterialDocument33 pagesCopyright Study MaterialHeaven DsougaNo ratings yet

- Interpretation of Statutes Summary Lectures 1 15Document56 pagesInterpretation of Statutes Summary Lectures 1 15Heena ShaikhNo ratings yet

- Emperor Vs Khwaja Nazir Ahmed 17101944 BOMHCM440096COM570560Document6 pagesEmperor Vs Khwaja Nazir Ahmed 17101944 BOMHCM440096COM570560Mayank RajpootNo ratings yet

- J M I N D: Amia Illia Slamia, EW ElhiDocument12 pagesJ M I N D: Amia Illia Slamia, EW ElhiShreya KumariNo ratings yet

- Civil Procedure CodeDocument21 pagesCivil Procedure CodePphidsuJaffarabadNo ratings yet

- Principles of Judgment Writing in Criminal TrialsDocument6 pagesPrinciples of Judgment Writing in Criminal TrialsVivek NandeNo ratings yet

- Language of Drafting Legal Document: - Hindi or English or RegionalDocument7 pagesLanguage of Drafting Legal Document: - Hindi or English or RegionalPrashant Kumar SinhaNo ratings yet

- Interpretation of StatuteDocument14 pagesInterpretation of Statutekhushbu guptaNo ratings yet

- New Horizons LTD, Another vs. Union of India 1995 I Com. L.J. 100 (SC) Main Facts of The CaseDocument3 pagesNew Horizons LTD, Another vs. Union of India 1995 I Com. L.J. 100 (SC) Main Facts of The Caseamit kashyapNo ratings yet

- 46516bosinterp2 Mod2 cp3Document24 pages46516bosinterp2 Mod2 cp3Vishnu V DevNo ratings yet

- Saving of Donations Mortis Causa and Muhammadan Law PDFDocument3 pagesSaving of Donations Mortis Causa and Muhammadan Law PDFSinghNo ratings yet

- Statutory InterpritationDocument9 pagesStatutory InterpritationSsebitosi DouglasNo ratings yet

- Interpretation of StatutesDocument61 pagesInterpretation of StatutesSurya J NNo ratings yet

- Res Subjudice and Res JudicataDocument7 pagesRes Subjudice and Res JudicatajerinNo ratings yet

- Internal Aids of Interpretation and Construction of StatutesDocument20 pagesInternal Aids of Interpretation and Construction of Statutesgagan deepNo ratings yet

- Election Law (Syllabus)Document2 pagesElection Law (Syllabus)Gaurav GehlotNo ratings yet

- Interpretation of Statutes - Student NotesDocument23 pagesInterpretation of Statutes - Student Notesahirvar.govindNo ratings yet

- Interpretation of StatutesDocument80 pagesInterpretation of StatutesShreshtha RaoNo ratings yet

- Unit I & IIDocument106 pagesUnit I & IIzenith chhablaniNo ratings yet

- SP-07 Memorial For The Respondents PDFDocument27 pagesSP-07 Memorial For The Respondents PDFTNNLS Placements67% (3)

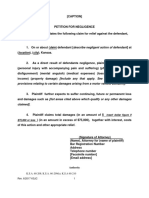

- Petition For Negligence (6-2017)Document1 pagePetition For Negligence (6-2017)Ranjan BaradurNo ratings yet

- R 450 Sample Memorial For Moot Court CompetitionDocument25 pagesR 450 Sample Memorial For Moot Court CompetitionRanjan BaradurNo ratings yet

- Placement Cell InvitationDocument3 pagesPlacement Cell InvitationRanjan BaradurNo ratings yet