0% found this document useful (0 votes)

310 views92 pagesImage Processing Techniques Overview

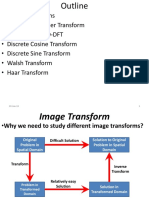

The document summarizes a lecture on image processing in the frequency domain. It discusses basis changes, which involve representing image data using a different set of basis vectors. This allows the image to be analyzed in different domains, including the spatial and frequency domains. Examples are provided to illustrate basis changes and writing image data in different bases, including the natural basis and a Walsh-Hadamard basis. Image compression techniques like the discrete cosine transform and JPEG are also mentioned.

Uploaded by

Surya Ashok PallalaCopyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as PPT, PDF, TXT or read online on Scribd

0% found this document useful (0 votes)

310 views92 pagesImage Processing Techniques Overview

The document summarizes a lecture on image processing in the frequency domain. It discusses basis changes, which involve representing image data using a different set of basis vectors. This allows the image to be analyzed in different domains, including the spatial and frequency domains. Examples are provided to illustrate basis changes and writing image data in different bases, including the natural basis and a Walsh-Hadamard basis. Image compression techniques like the discrete cosine transform and JPEG are also mentioned.

Uploaded by

Surya Ashok PallalaCopyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as PPT, PDF, TXT or read online on Scribd