Professional Documents

Culture Documents

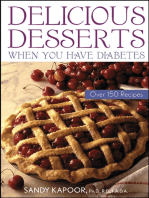

Figure 2 Annual CPI Inflation Rates.: UK The

Uploaded by

koraOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Figure 2 Annual CPI Inflation Rates.: UK The

Uploaded by

koraCopyright:

Available Formats

Collapse of Bretton

Woods

16

14 25

14 End of the Collapse

volcker 12 Stage III

12 20 of Bretton

stabilisation of

Woods

10 EMU

10

begins 15

8 8

6 10

6

4

4 Collapse

2 5

of Bretton

2 Woods

0

0

–2

1970 1980 1990 2000 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 1970 1980 1990 2000

2000 2005 Japan

Floating of United States Euro area

the Introduction of

pound inflation targeting

18

UK Introduction Introduction

25 joins of inflation 16

12 of inflation

the 14 targeting

20 targeting 12

ERM 10

8 10

15

8

6

10 6

4

4 Collapse

Collapse

5 of Bretton 2 of Bretton

4 2

Woods

Woods 0

0 0

1970 1980 1990 2000 1970 1980 1990 2000 1970 1980 1990 2000

United Kingdom Canada Australia

Figure 2 Annual CPI inflation rates.

Monetary Policy Regimes and Economic Performance 1223

monetary policy is now neither comfortable nor communautaire. The new European

Sys- temic Risk Board (ESRB) has yet to start work, and we do not know how it will

operate. This underscores a wider point: laws and governments (and central banks) are

national, whereas the financial system is global, and almost all the large financial

interme- diaries are cross-border — “international in life, but national in death.”

There are two obvious alternatives. First, one can try to make the key laws,

especially insolvency laws for systemic financial intermediaries, and governance and

regulation mechanisms via the FSB and BCBS, international. But would the U.S.

Congress accept a law drafted by foreigners; would the Europeans accept whatever

regulatory policies to which the

U.S. finally agree? What about the rest of the world? Failing that, and failure does

seem the most likely outcome, the other logical solution is to give regulatory control

back to the host countries, causing frictions to the global financial system, and making

cross-border banks effectively into holding companies for separate national banks. Since

neither outcome is palatable, the probable result will be muddle and confusion.

Just a scant couple of years ago, the role and constitutional position of central banks

seemed assured. They should be independent (within the public sector) and deploy

their single instrument of interest rates primarily to achieve a low and stable inflation

rate. If financial disturbance threatened the macroeconomic outlook, a judicious

but determined adjustment of interest rates could pick up the pieces. And it worked,

bril- liantly and successfully, for about 15 years. But now the financial crisis has re-

opened old questions and raised new ones; prior certainties have been flushed away.

How these questions may be answered may be the subject of a similar chapter in the

next Handbook.

APPENDIX

1 The data

Here is a detailed description of the data underlying each figure.

Figure 1 United States: Real GDP is GDPC96,80 GDL deflator inflation is based

on GDPCTPI, and the short-term rate is the federal funds rate

(FEDFUNDS).

Euro area: All of the series are from the ECB’s Area Wide Model’s (AWM) data-

base. Japan: Real GDP and the GDP deflator are from the OECD’s Quarterly

National Accounts (QNA.Q.JPN.EXPGDP.LNBARSA.2000_S1 and QNA.Q.

JPN.EXPGDP.DNBSA.2000_S1), the short-term rate is the call money rate from

the International Monetary Fund’s International Financial Statistics IMF and IFS,

respectively), and the CPI is from the IMF’s IFS. United Kingdom: Real

GDP

80

Unless specified otherwise, all of the acronyms for the United States refer to FREDII, the database found at the

St. Louis FED’s Web site.

You might also like

- Pestle AustriaDocument1 pagePestle AustriaRananjay Singh100% (1)

- The Toyota Kata Practice Guide: Practicing Scientific Thinking Skills for Superior Results in 20 Minutes a DayFrom EverandThe Toyota Kata Practice Guide: Practicing Scientific Thinking Skills for Superior Results in 20 Minutes a DayRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (7)

- MPD Special Operations Unit DocumentDocument24 pagesMPD Special Operations Unit DocumentMatt WinterNo ratings yet

- The Fusion Marketing Bible: Fuse Traditional Media, Social Media, & Digital Media to Maximize MarketingFrom EverandThe Fusion Marketing Bible: Fuse Traditional Media, Social Media, & Digital Media to Maximize MarketingRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Nielsen India FMCG Snapshot - Q2'20 - DeckDocument23 pagesNielsen India FMCG Snapshot - Q2'20 - DeckAshish GandhiNo ratings yet

- Ebouk Monetary Economics 10Document2 pagesEbouk Monetary Economics 10koraNo ratings yet

- Boating Accident Statistical ReportDocument24 pagesBoating Accident Statistical ReportABC Action NewsNo ratings yet

- Monthly Cases of Dengue Fever Admitted in Tubigon Community Hospital: Tubigon ResidentsDocument2 pagesMonthly Cases of Dengue Fever Admitted in Tubigon Community Hospital: Tubigon ResidentsGina BoligaoNo ratings yet

- Pridicting The Markets Nov2020 - ch1Document14 pagesPridicting The Markets Nov2020 - ch1scribbugNo ratings yet

- BSG002A BattlestarGalactica FasterThanLight PNP enDocument44 pagesBSG002A BattlestarGalactica FasterThanLight PNP enTransbugoyNo ratings yet

- Warehouse Pak Yono-ColumnDocument1 pageWarehouse Pak Yono-ColumnSyach FirmNo ratings yet

- F20 Attendance Register - 1 March 2019Document1 pageF20 Attendance Register - 1 March 2019roni amiruddinNo ratings yet

- Predicting The Past - 18oct23Document14 pagesPredicting The Past - 18oct23scribbugNo ratings yet

- Gemma Jacket Template: Print OUT & KeepDocument33 pagesGemma Jacket Template: Print OUT & KeepbogeszNo ratings yet

- Deluxe Double Fat Stratocaster 0133300Document4 pagesDeluxe Double Fat Stratocaster 0133300Day IskandarNo ratings yet

- Wonderful TonightDocument5 pagesWonderful TonightIvan PanucoNo ratings yet

- Cheia de Manias Raa NegraDocument2 pagesCheia de Manias Raa NegraJose Vinicius Macedo TreibNo ratings yet

- 6 Nos. Truss Reqd. As Drn. Mkd. Tr3: Erection Mkd. Item NO. Section Length Erection Mkd. Item NO. Section LengthDocument1 page6 Nos. Truss Reqd. As Drn. Mkd. Tr3: Erection Mkd. Item NO. Section Length Erection Mkd. Item NO. Section LengthMridupaban DuttaNo ratings yet

- Hard To Count Areas - Mass.Document1 pageHard To Count Areas - Mass.Massachusetts Council of Human Service ProvidersNo ratings yet

- LS57 Wrap SkirtDocument39 pagesLS57 Wrap Skirtdaisy22No ratings yet

- Gasgas FSE EC SM 400 450 2005 Manual de Reparatie WWW - Manuale-Reparatie - Eu PDFDocument34 pagesGasgas FSE EC SM 400 450 2005 Manual de Reparatie WWW - Manuale-Reparatie - Eu PDFRobi Junc100% (1)

- 8FG D CE048-09 - 0608 P SteeringDocument21 pages8FG D CE048-09 - 0608 P SteeringDuong Van HoanNo ratings yet

- The Power of Scarcity: Leveraging Urgency and Demand to Influence Customer DecisionsFrom EverandThe Power of Scarcity: Leveraging Urgency and Demand to Influence Customer DecisionsNo ratings yet

- Dutch Cone Penetration TestDocument5 pagesDutch Cone Penetration TestKobelNo ratings yet

- D Minor Pentatonic Scale - Bends - VibratoDocument1 pageD Minor Pentatonic Scale - Bends - VibratoPete SklaroffNo ratings yet

- Launch Escape System Lattice & SkirtDocument4 pagesLaunch Escape System Lattice & SkirtThar LattNo ratings yet

- River 295Document12 pagesRiver 295HelenNo ratings yet

- Numbers 1-100 CrosswordDocument1 pageNumbers 1-100 CrosswordMaria Isabel MNo ratings yet

- Case Exploded ViewDocument1 pageCase Exploded ViewNirmani HansiniNo ratings yet

- Cased Hole Logging 1675536439Document31 pagesCased Hole Logging 1675536439Prakash JadhavNo ratings yet

- Bender PlansDocument15 pagesBender PlansMike Nichlos80% (5)

- Mark VIII British TankDocument10 pagesMark VIII British TankMr. PicklesNo ratings yet

- A Minor Pentatonic ScaleDocument1 pageA Minor Pentatonic ScaleJared BerrimanNo ratings yet

- Assembly Rafi RATCHETDocument1 pageAssembly Rafi RATCHETrachmatNo ratings yet

- Ridgid No. 460-6 TristandDocument1 pageRidgid No. 460-6 TristandenriqueNo ratings yet

- Standard Stratocaster HSS 013-4700 - 02C - SISDDocument4 pagesStandard Stratocaster HSS 013-4700 - 02C - SISDJose GarciaNo ratings yet

- Gizzard Proventriculus Health Marker Avinews Int Sept 22Document11 pagesGizzard Proventriculus Health Marker Avinews Int Sept 22mohamed helmyNo ratings yet

- The Private Sector Financial Balance As A Predictor of Financial CrisesDocument12 pagesThe Private Sector Financial Balance As A Predictor of Financial CrisesIsaac GoldNo ratings yet

- Cone 2Document1 pageCone 2Yhonni IrwanNo ratings yet

- Episode 87 Hirajoshi ScaleDocument2 pagesEpisode 87 Hirajoshi ScalexavinwonderlandNo ratings yet

- Longitudinal BEAM Reinforcement - 2Document1 pageLongitudinal BEAM Reinforcement - 2Ciprian ShaolinNo ratings yet

- Useful Stuff ChartsDocument5 pagesUseful Stuff ChartsDevilish LuciferNo ratings yet

- Traffic Management WorkshopDocument3 pagesTraffic Management Workshopcahyo prambudiNo ratings yet

- NullDocument20 pagesNullBrayan NohNo ratings yet

- Gear Box SHEET 2 PDFDocument1 pageGear Box SHEET 2 PDFburzin wadiaNo ratings yet

- 42 - Drill Head Assembly FinalDocument1 page42 - Drill Head Assembly Finaladmam jones50% (2)

- Modes in Key of C: Standard TuningDocument1 pageModes in Key of C: Standard TuningGüney GencolNo ratings yet

- Cent 178 PumpsDocument2 pagesCent 178 PumpsJulian Felipe Noguera CruzNo ratings yet

- 5Document22 pages5juan carlos zavalaNo ratings yet

- 013-3100C Sisd PDFDocument4 pages013-3100C Sisd PDFCarl Ivan Gambala100% (1)

- 013-3100C Sisd PDFDocument4 pages013-3100C Sisd PDFCarl Ivan GambalaNo ratings yet

- Study Planner PDFDocument1 pageStudy Planner PDFCara DantonNo ratings yet

- ACFrOgDKyRDE3p3 rSdDxV593ewmrwv9vBGZ1n5f2z7ryr1ifo7GGgOAS65ivf8KXCTxvbGFIB2Ctbp-z8YrJUmisxtdN4Fxw3KotjoDxDd36t wBQu9Gjlx sROsCI PDFDocument1 pageACFrOgDKyRDE3p3 rSdDxV593ewmrwv9vBGZ1n5f2z7ryr1ifo7GGgOAS65ivf8KXCTxvbGFIB2Ctbp-z8YrJUmisxtdN4Fxw3KotjoDxDd36t wBQu9Gjlx sROsCI PDFTeeraphat KreekunNo ratings yet

- ACFrOgDKyRDE3p3 rSdDxV593ewmrwv9vBGZ1n5f2z7ryr1ifo7GGgOAS65ivf8KXCTxvbGFIB2Ctbp-z8YrJUmisxtdN4Fxw3KotjoDxDd36t wBQu9Gjlx sROsCIDocument1 pageACFrOgDKyRDE3p3 rSdDxV593ewmrwv9vBGZ1n5f2z7ryr1ifo7GGgOAS65ivf8KXCTxvbGFIB2Ctbp-z8YrJUmisxtdN4Fxw3KotjoDxDd36t wBQu9Gjlx sROsCITeeraphat KreekunNo ratings yet

- ACFrOgDKyRDE3p3 rSdDxV593ewmrwv9vBGZ1n5f2z7ryr1ifo7GGgOAS65ivf8KXCTxvbGFIB2Ctbp-z8YrJUmisxtdN4Fxw3KotjoDxDd36t wBQu9Gjlx sROsCIDocument1 pageACFrOgDKyRDE3p3 rSdDxV593ewmrwv9vBGZ1n5f2z7ryr1ifo7GGgOAS65ivf8KXCTxvbGFIB2Ctbp-z8YrJUmisxtdN4Fxw3KotjoDxDd36t wBQu9Gjlx sROsCITeeraphat KreekunNo ratings yet

- 2022 Tallahassee Marathon MapDocument1 page2022 Tallahassee Marathon MapWCTV Digital TeamNo ratings yet

- Mark Armstrong - Swinging Classical Play-Along (BB)Document1 pageMark Armstrong - Swinging Classical Play-Along (BB)Calixto AlvarezNo ratings yet

- Instructions Ec120bDocument2 pagesInstructions Ec120bAlejandro MamaniNo ratings yet

- Inverseur TTMC35 A & PDocument12 pagesInverseur TTMC35 A & PDavid dounaiNo ratings yet

- Set Date of Kidding Time (Step 10) First To Determine Approximate Dates of Other Management StepsDocument3 pagesSet Date of Kidding Time (Step 10) First To Determine Approximate Dates of Other Management StepsDinora RuizNo ratings yet

- 291085Document2 pages291085Denis MartiniNo ratings yet

- Ebouk Monetary Economics 08Document2 pagesEbouk Monetary Economics 08koraNo ratings yet

- 3.2 Model Misspecification: Lars Peter Hansen and Thomas J. SargentDocument2 pages3.2 Model Misspecification: Lars Peter Hansen and Thomas J. SargentkoraNo ratings yet

- Ebouk Monetary Economics 05Document2 pagesEbouk Monetary Economics 05koraNo ratings yet

- Ebouk Monetary Economics 03Document4 pagesEbouk Monetary Economics 03koraNo ratings yet

- 6.3 Political and Monetary UnionDocument2 pages6.3 Political and Monetary UnionkoraNo ratings yet

- Ebouk Monetary Economics 05Document2 pagesEbouk Monetary Economics 05koraNo ratings yet

- Ebouk Monetary Economics 03Document2 pagesEbouk Monetary Economics 03koraNo ratings yet

- Fara Laynds Lamborghini - 0910233039Document18 pagesFara Laynds Lamborghini - 0910233039layndsyellowroseNo ratings yet

- Case StudyDocument2 pagesCase StudyJames Bryle GalagnaraNo ratings yet

- Japanese Yen Per USDDocument7 pagesJapanese Yen Per USDShoaibUlHassanNo ratings yet

- Historical Chart of Pakistan Rupee Exchange Rate vs. US DollarDocument2 pagesHistorical Chart of Pakistan Rupee Exchange Rate vs. US DollarGENIUS1507No ratings yet

- 60mun'23 G-20 Study GuideDocument15 pages60mun'23 G-20 Study GuideFSAL MUNNo ratings yet

- Global Economic Impact Study of Shopify: April 2021Document38 pagesGlobal Economic Impact Study of Shopify: April 2021darkjfman_680607290No ratings yet

- The Bretton Woods InstitutionsDocument2 pagesThe Bretton Woods InstitutionsAtharva MapuskarNo ratings yet

- So What Is A Recession?Document7 pagesSo What Is A Recession?silverlookzNo ratings yet

- Forex StrategyDocument11 pagesForex StrategyNoman Khan100% (1)

- AssignmentDocument1 pageAssignmentRyan Dave MalnegroNo ratings yet

- The Financial Crisis, Comparison With Covid and Outlook - VFDocument68 pagesThe Financial Crisis, Comparison With Covid and Outlook - VFsebastian ramirezNo ratings yet

- GEP January 2023 Executive SummaryDocument2 pagesGEP January 2023 Executive SummaryRuslanNo ratings yet

- Lecture 1 Changing Global Economic LandscapeDocument57 pagesLecture 1 Changing Global Economic LandscapeashikNo ratings yet

- Fiscal and Monetary Policy Under Floating and Fixed Exchange RateDocument5 pagesFiscal and Monetary Policy Under Floating and Fixed Exchange RateNerea FrancesNo ratings yet

- GREECE DEBT CRISIS Final Presentation 1Document9 pagesGREECE DEBT CRISIS Final Presentation 1Abhinandan Kumar100% (1)

- Calendar Sinnother Articles - 22-23 and QuestionnaireDocument3 pagesCalendar Sinnother Articles - 22-23 and QuestionnaireBittelNo ratings yet

- Srilankan Economic CrisisDocument7 pagesSrilankan Economic CrisisDebojyoti Roy100% (1)

- Pakistan and US War On TerrorDocument21 pagesPakistan and US War On TerrorMuhammad BilalNo ratings yet

- Artikel Bahasa InggrisDocument3 pagesArtikel Bahasa InggrisBulanxBintangNo ratings yet

- Comparative Study On Global Financial LawsDocument14 pagesComparative Study On Global Financial Lawsmadhan100% (1)

- Artikel SPM AsetDocument21 pagesArtikel SPM AsetAdrianus Victor PurnomoNo ratings yet

- The Global Financial Crisis and The Challenge To Neoliberalism ...Document11 pagesThe Global Financial Crisis and The Challenge To Neoliberalism ...ian laurence pedranoNo ratings yet

- Global Financial Crisis Vocabulary 2022Document6 pagesGlobal Financial Crisis Vocabulary 2022Roney PlazasNo ratings yet

- What Is The Asian Financial Crisis - IB Unit 4Document2 pagesWhat Is The Asian Financial Crisis - IB Unit 4ApurvaNo ratings yet

- YES BANK CRISES (FM) (Sem 4)Document2 pagesYES BANK CRISES (FM) (Sem 4)aryan sharmaNo ratings yet

- Choose A Topic Related To Any Subject From Your Major. Choose A Presentation Date Fill in The Information in The Excel FileDocument2 pagesChoose A Topic Related To Any Subject From Your Major. Choose A Presentation Date Fill in The Information in The Excel FileLucas MazónNo ratings yet

- LiteratureReview Reyes E MarxDocument7 pagesLiteratureReview Reyes E MarxMariecris TapiaNo ratings yet

- The Asian Financial Crisis of 1997Document1 pageThe Asian Financial Crisis of 1997Đăng Hiếu LươngNo ratings yet