Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Japanese Literature

Uploaded by

krampy0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

30 views25 pagesOriginal Title

Japanese-Literature (1) (1) (1) (1)

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

30 views25 pagesJapanese Literature

Uploaded by

krampyCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 25

Japanese literature

Japanese literature is one of the major literatures of the world, comparable to

English literature in age and variety. From the seventh century C.E., when the

earliest surviving works were written, until the present day, there has never

been a period when literature was not being produced in Japan. Possibly the

earliest full-length novel, The Tale of Genji was written in Japan in the early

eleventh century. In addition to novels, poetry, and drama, other genres such as

travelogues, personal diaries and collections of random thoughts and

impressions, are prominent in Japanese literature. In addition to works in the

Japanese language, Japanese writers produced a large body of writing in

classical Chinese.

Japanese Literature is generally divided into three main periods: Ancient,

Medieval, and Modern.

Characteristics of Japanese

Literature

• Japanese literature can be difficult to read and

understand

• Statements are often ambiguous, omitting as

unnecessary the particles of speech which would

normally identify words as the subject or object of a

sentence, or using colloquial verb forms from a

specific region or social class.

• In many cases the significance of a simple sentence

can only be understood by someone who is familiar

with the cultural or historical background of the work.

• The nature of the Japanese language influenced the

development of poetic forms.

• All Japanese words end in one of five simple vowels, making

it difficult to construct effective rhymes.

• Japanese words also lack a stress accent, so that poetry was

distinguished from prose mainly by being divided into lines

of specific numbers of syllables rather than by cadence and

rhythm.

• These characteristics made longer poetic forms difficult, and

most Japanese poems are short, their poetic quality coming

from rich allusions and multiple meanings evoked by each

word used in the composition.

Main Periods of Japanese

Literature

Ancient Literature (until 894)

• Before the introduction of kanji from China, there was no writing

system in Japan.

• Chinese characters were used in Japanese syntactical formats, and the

literary language was classical Chinese; resulting in sentences that

looked like Chinese but were phonetically read as Japanese.

• Chinese characters were used, not for their meanings, but because

they had a phonetic sound which resembled a Japanese word.

• Chinese characters were later adapted to write Japanese speech,

creating what is known as the man'yōgana, the earliest form of kana,

or syllabic writing.

• The earliest works were created in the Nara Period.

• Kojiki (712: a work recording Japanese mythology and legendary history)

• Nihonshoki (720; a chronicle with a slightly more solid foundation in historical

records than Kojiki)

• Man'yōshū (Ten Thousand Leaves, 759); an anthology of poetry.

Classical Literature (894-1194; The Heian

Period)

• consider a golden era of art and literature.

• The Tale of Genji (early eleventh century) by Murasaki Shikibu

• Kokin Wakashū (905, waka poetry anthology)

• The Pillow Book (990s), an essay about the life, loves, and pastimes of

nobles in the Emperor's court written by Murasaki Shikibu's

contemporary and rival, Sei Shonagon

• During this time, the imperial court patronized poets, many of whom

were courtiers or ladies-in-waiting. Editing anthologies of poetry was

a national pastime.

Medieval Literature (1195 - 1600)

• is marked by the strong influence of Zen Buddhism, and many writers

were priests, travelers, or ascetic poets

• Japan experienced many civil wars which led to the development of a

warrior class, and a widespread interest in war tales, histories, and

related stories

• The Tale of the Heike (1371), an epic account of the struggle between

the Minamoto and Taira clans for control of Japan at the end of the

twelfth century.

Early-Modern Literature (1600-1868)

• The literature of this time was written during the generally peaceful

Tokugawa Period (commonly referred to as the Edo Period).

• forms of popular drama developed which would later evolve

into kabuki(traditional Japanese theater).

• Many genres of literature made their début during the Edo Period,

inspired by a rising literacy rate among the growing population of

townspeople, as well as the development of lending libraries.

Meiji, Taisho, and Early Showa literature

(1868-1945)

• The Meiji era marked the re-opening of Japan to the West, and a

period of rapid industrialization.

• Young Japanese prose writers and dramatists struggled with a whole

galaxy of new ideas and artistic schools, but novelists were the first to

successfully assimilate some of these concepts

• In the early Meiji era (1868-1880s), Fukuzawa Yukichi and Nakae

Chomin authored Enlightenment literature, while pre-modern popular

books depicted the quickly changing country

• Higuchi Ichiyo, a rare woman writer in this era, wrote short stories on

powerless women of this age in a simple style, between literary and

colloquial. Izumi Kyoka, a favored disciple of Ozaki, pursued a flowing

and elegant style and wrote early novels such as The Operating

Room (1895) in literary style and later ones including The Holy Man of

Mount Koya (1900) in colloquial language.

• Mori Ogai introduced Romanticism to Japan with his anthology of

translated poems (1889), and it was carried to its height by Shimazaki

Toson and his contemporaries and by the

magazines Myōjō and Bungaku-kai in the early 1900s.

• Shimazaki shifted from Romanticism to Naturalism, which was

established with the publication of The Broken Commandment (1906)

and Katai Tayama's Futon (1907).

• Naturalism led to the “I” novel. Neo-romanticism came out of anti-

naturalism and was led by Nagai Kafu, Junichiro Tanizaki, Kotaro

Takamura, Kitahara Hakushu and others during the early 1910s.

Mushanokoji Saneatsu, Shiga Naoya and others founded a

magazine, Shirakaba, in 1910 to promote Humanism.

• War-time Japan saw the début of several authors best known for the

beauty of their language and their tales of love and sensuality,

• Japan's first winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature, Kawabata

Yasunari, a master of psychological fiction.

Post-War Literature

• Japan’s defeat in World War II influenced Japanese literature during

the 1940s and 1950s.

• Many authors wrote stories about disaffection, loss of purpose, and

the coping with defeat.

• Dazai Osamu's novel The Setting Sun tells of a soldier returning from

Manchukuo. Mishima Yukio, well known for both his nihilistic writing

and his controversial suicide by seppuku

• Prominent writers of the 1970s and 1980s were identified with

intellectual and moral issues in their attempts to raise social and

political consciousness.

• Oe Kenzaburo wrote his best-known work, A Personal Matter in 1964

and became Japan's second winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature.

• Murakami Haruki is one of the most popular and controversial of

today's Japanese authors. His genre-defying, humorous and surreal

works have sparked fierce debates in Japan over whether they are

true "literature" or simple pop-fiction:

Modern Themes

• Although modern Japanese writers covered a wide variety of subjects,

one particularly Japanese approach stressed their subjects' inner

lives, widening the earlier novel's preoccupation with the narrator's

consciousness

• In keeping with the general trend toward reaffirming national

characteristics, many old themes re-emerged in modern literature,

and some authors turned consciously to the past.

• There was a growing emphasis on women's roles, the Japanese

persona in the modern world, and the malaise of common people lost

in the complexities of urban culture.

Common Modern Themes

• Japan has produced many literary "schools." Loyalty, obligation, and self-sacrifice

compromised by human emotion and affected by elements of the supernatural are

major themes of classic Japanese literature.

• “Kisetsukan” (“the feel of the season”) is an important concept in Japanese cultural and

artistic traditions. The Japanese often write about the seasons in their correspondence.

• The changing seasons is a theme addressed in “The Take of Genji”, an influential 11th

century novel. The poems in the “Kokin Wakashu”, an anthology of waka poems

compiled in the 10th century, are arranged in the order of the seasons. In haiku, every

poem must contain an appropriate “kigo” (‘season word”). There is even a book that

lists all recognized kigo by season.

• “Monogatari”, a style of literary narrative that concentrates on the life of a single

character, was used in the “Tale of Genji” and is still used in television dramas today.

Contemporary Literature

• Popular fiction, non-fiction, and children's literature all flourished in

urban Japan during the 1980s.

• Many popular works fell between "pure literature" and pulp novels,

including all sorts of historical serials, information-packed

docudramas, science fiction, mysteries, detective fiction, business

stories, war journals, and animal stories.

• Manga (comic books) have penetrated almost every sector of the

popular market. They include virtually every field of human interest,

such as a multi volume high-school history of Japan and, for the adult

market, a manga introduction to economics, and pornography.

Japanese Haiku

“Lighting One Candle” by Yosa Buson

The light of a candle

Is transferred to another candle—

Spring twilight

• Haikus focus on a brief moment in time,

juxtaposing two images, and creating a

sudden sense of enlightenment. A good

example of this is haiku master Yosa Buson’s

comparison of a singular candle with the

starry wonderment of the spring sky.

“The Old Pond” by Matsuo Bashō

An old silent pond

A frog jumps into the pond—

Splash! Silence again.

• This traditional example comes from Matsuo Bashō,

one of the four great masters of Haiku. Historically,

haikus are a derivative of the Japanese Hokku. Hokkus

are collaborative poems which follow the 5/7/5 rule.

They are meant to comment on the season or

surroundings of the authors and create some sort of

contrasting imagery separated by a kireji or “cutting

word” (like “Splash!”).

Rashōmon by Akutagawa Ryūnosuke

• The story, set in 12th-century Kyōto, reveals in spare and elegant

language the thoughts of a man on the edge of a life of crime and the

incident that pushes him over the brink. Combined with Akutagawa’s later

story “Yabu no naka” (1921; “In a Grove”), “Rashōmon” was the starting

point for Japanese director Kurosawa Akira’s classic

film Rashōmon (1950).

• the lesson is most probably this. Human beings are inevitably duplicitous

and self-serving, but if only they would develop the courage and

decency to admit the “truth” about themselves, the world would be a

better place.

• The story was first published in 1915 in Teikoku Bungaku. Akira

Kurosawa's film Rashomon (1950) is in fact based primarily on

another of Akutagawa's short stories, "In a Grove"; only the film's title

and some of the material for the frame scenes, such as the theft of a

kimono and the discussion of the moral ambiguity of thieving to

survive, are borrowed from "Rashōmon".

You might also like

- Anthology of Japanese Literature: From the Earliest Era to the Mid-Nineteenth CenturyFrom EverandAnthology of Japanese Literature: From the Earliest Era to the Mid-Nineteenth CenturyNo ratings yet

- Japanese Literature Report FinalllDocument23 pagesJapanese Literature Report FinalllkrampyNo ratings yet

- Japanese-Literature Report FinalDocument23 pagesJapanese-Literature Report FinalkrampyNo ratings yet

- Japanese-Literature Report FinalDocument23 pagesJapanese-Literature Report FinalkrampyNo ratings yet

- Japanese Literature Report FinalllDocument23 pagesJapanese Literature Report FinalllkrampyNo ratings yet

- Japanese Literature Report FinalllDocument23 pagesJapanese Literature Report FinalllkrampyNo ratings yet

- Japanese LiteratureDocument23 pagesJapanese LiteraturekrampyNo ratings yet

- Japanese LiteratureDocument25 pagesJapanese LiteraturekrampyNo ratings yet

- Japanese-Literature Report FinallDocument23 pagesJapanese-Literature Report FinallkrampyNo ratings yet

- Japanese LiteratureDocument24 pagesJapanese LiteratureCharm BartolomeNo ratings yet

- Japanese LiteratureDocument26 pagesJapanese LiteratureSarah Jean100% (1)

- 13japaneseliterature Mondilla 160816123659Document23 pages13japaneseliterature Mondilla 160816123659rickyjayfernandez572No ratings yet

- Crim 314 - FL - PPPDocument45 pagesCrim 314 - FL - PPPBaby Jane Ngujo - BundacNo ratings yet

- Japan LiteratureDocument9 pagesJapan LiteratureJazzd Sy GregorioNo ratings yet

- Japanese LiteratureDocument53 pagesJapanese LiteratureCecille RadocNo ratings yet

- Japanese LiteratureDocument15 pagesJapanese LiteratureEzekiel D. Rodriguez93% (14)

- Japanese LiteratureDocument29 pagesJapanese LiteratureMaria Rizza LuchavezNo ratings yet

- Japanese LiteratureDocument9 pagesJapanese LiteratureMarco Louie ManejaNo ratings yet

- Country Report Japan PresentationDocument27 pagesCountry Report Japan PresentationJeziel NecioNo ratings yet

- Japanese LiteratureDocument7 pagesJapanese LiteratureSantiago Jr KadusaleNo ratings yet

- Japanese Literature FinaleDocument15 pagesJapanese Literature FinalekrampyNo ratings yet

- The Rise of Popular Arts in Pre-Modern Japan: Vol. D (1650-1800) Also Called "The Edo Period"Document49 pagesThe Rise of Popular Arts in Pre-Modern Japan: Vol. D (1650-1800) Also Called "The Edo Period"mil salinasNo ratings yet

- A Brief History of Japanese LiteratureDocument32 pagesA Brief History of Japanese LiteratureAbigail BascoNo ratings yet

- 21st HODocument2 pages21st HONashimahNo ratings yet

- Nippon, The Land of The Rising SunDocument33 pagesNippon, The Land of The Rising SunStefanie Louise Taguines Santos100% (1)

- 21st Century Lit 5Document8 pages21st Century Lit 5SEAN DARYL TACATANo ratings yet

- Literature of JapanDocument10 pagesLiterature of JapanKarenJaneAguilarCandelariaNo ratings yet

- Japanese LiteratureDocument13 pagesJapanese LiteraturePepe CuestaNo ratings yet

- History of Japanese LiteratureDocument17 pagesHistory of Japanese LiteratureSkux LearnerNo ratings yet

- Japanese LiteratureDocument3 pagesJapanese LiteratureJen EstebanNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 Lesson 2 JapanDocument6 pagesChapter 2 Lesson 2 JapanMc Kevin Jade MadambaNo ratings yet

- Japanese Literature: Prepared By: Gesha Mea J. BuddahimDocument16 pagesJapanese Literature: Prepared By: Gesha Mea J. BuddahimGed Rocamora100% (1)

- Nara Literature (Before 794) : KanjiDocument4 pagesNara Literature (Before 794) : KanjiIdrian Camilet100% (1)

- Period of Japanese LitDocument48 pagesPeriod of Japanese LitJoaquin Emilio MercadoNo ratings yet

- Jp114t Term PaperDocument9 pagesJp114t Term PaperPallavi TiwariNo ratings yet

- Japanese LiteratureDocument6 pagesJapanese LiteratureRhodora A. BorjaNo ratings yet

- RWS Second Quarter HandoutsDocument10 pagesRWS Second Quarter HandoutsFrans JabalNo ratings yet

- Japanese LiteratureDocument24 pagesJapanese LiteratureMike James Rudio AgnesNo ratings yet

- Group-4 Japanese LiteratureDocument67 pagesGroup-4 Japanese LiteratureSherlyn DelacruzNo ratings yet

- Japanese LiteratureDocument2 pagesJapanese LiteratureClarisa Jane CanlasNo ratings yet

- 2nd Quarter LESSON 3Document7 pages2nd Quarter LESSON 3Salve BayaniNo ratings yet

- Asian LiteratureDocument5 pagesAsian LiteratureKeith OlfindoNo ratings yet

- 21st Century Literature q2 - Asia, Middle East and AfricaDocument10 pages21st Century Literature q2 - Asia, Middle East and AfricaHazel Loraenne ConarcoNo ratings yet

- Japanese LiteratureDocument15 pagesJapanese LiteratureNinaNo ratings yet

- Japanese Lit12Document33 pagesJapanese Lit12Claudia SalduaNo ratings yet

- Asian Literature Reading MaterialDocument6 pagesAsian Literature Reading MaterialErlindaGermonoCeraldeNo ratings yet

- 7 East Asian LiteratureDocument69 pages7 East Asian LiteraturemcasmbNo ratings yet

- Japaneseliterature 1302180543bbbbbbbbbDocument27 pagesJapaneseliterature 1302180543bbbbbbbbbClara ArejaNo ratings yet

- Japanese LitDocument9 pagesJapanese LitAntoinette San JuanNo ratings yet

- Ali 314 Lecture Notes, 2023Document68 pagesAli 314 Lecture Notes, 2023mutaniabridgitNo ratings yet

- Module 1-HandoutDocument11 pagesModule 1-HandoutJulieSanchezErsandoNo ratings yet

- Aileen R. Suanino Beed Iv JULY13, 2019 Japanese Literatue: Japan Asian DramaDocument6 pagesAileen R. Suanino Beed Iv JULY13, 2019 Japanese Literatue: Japan Asian DramaMike MlNo ratings yet

- Asian-Literatures Chinese Singaporean - and - JapaneseDocument3 pagesAsian-Literatures Chinese Singaporean - and - JapaneseRichlyNo ratings yet

- Literature of China and JapanDocument32 pagesLiterature of China and JapanKarlo Dave BautistaNo ratings yet

- JapaneesDocument76 pagesJapaneesSameeraPereraNo ratings yet

- Japanese LiteratureDocument36 pagesJapanese LiteratureNiño Gerard Jabagat100% (4)

- Students Copy Lesson 2 2nd QuarterDocument28 pagesStudents Copy Lesson 2 2nd QuarterBenedict Joshua S. DiaganNo ratings yet

- Asian LiteratureDocument24 pagesAsian LiteratureJustine Tristan B. CastilloNo ratings yet

- 21st Century qr.2Document14 pages21st Century qr.2maedeguia078No ratings yet

- International News FinalDocument3 pagesInternational News FinalkrampyNo ratings yet

- Campus Jour DraftDocument6 pagesCampus Jour DraftkrampyNo ratings yet

- Japanese LiteratureDocument25 pagesJapanese LiteraturekrampyNo ratings yet

- Japanese-Literature Report FinallDocument23 pagesJapanese-Literature Report FinallkrampyNo ratings yet

- Japanese LiteratureDocument23 pagesJapanese LiteraturekrampyNo ratings yet

- Japanese Literature FinaleDocument15 pagesJapanese Literature FinalekrampyNo ratings yet

- SQL Queries AllDocument26 pagesSQL Queries AllThontla Subba ReddyNo ratings yet

- At The Hospital Quick Reference Glossary PDFDocument12 pagesAt The Hospital Quick Reference Glossary PDFFaisal IqbalNo ratings yet

- Culture: W ElcomeDocument10 pagesCulture: W Elcomelaurent burneauNo ratings yet

- CBSE Class 10 English Language and Literature Question Paper Solved 2019 Set LDocument14 pagesCBSE Class 10 English Language and Literature Question Paper Solved 2019 Set LWeeSky 24No ratings yet

- Câu 8 - Phrasal Verbs - Trư NG THPT Mai Thúc LoanDocument2 pagesCâu 8 - Phrasal Verbs - Trư NG THPT Mai Thúc LoanTúNo ratings yet

- The Japanese PeriodDocument7 pagesThe Japanese PeriodSteve PlanasNo ratings yet

- The Test of Full Blast 2Document3 pagesThe Test of Full Blast 2zahraNo ratings yet

- Assignment 1Document6 pagesAssignment 1Ly NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 - Lexical AnalysisDocument51 pagesChapter 3 - Lexical AnalysisasdghhNo ratings yet

- France Is ADocument4 pagesFrance Is AGrayNo ratings yet

- Language Learning Strategies Chapter I (Language Learning Style)Document4 pagesLanguage Learning Strategies Chapter I (Language Learning Style)Rika SuhayaniNo ratings yet

- Towards Spontaneous Style Modeling With Semi-Supervised Pre-Training For Conversational Text-to-Speech SynthesisDocument5 pagesTowards Spontaneous Style Modeling With Semi-Supervised Pre-Training For Conversational Text-to-Speech SynthesisbilletonNo ratings yet

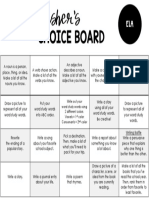

- Early Finishers Choice BoardDocument1 pageEarly Finishers Choice BoardKathleen JonesNo ratings yet

- ENG 118 - Listening - Level 1 - 2020S - Lecture Slides - 07, 08Document37 pagesENG 118 - Listening - Level 1 - 2020S - Lecture Slides - 07, 08Bảo KhanhNo ratings yet

- Past Simple Test: A. Write The Past Forms of The Regular and Irregular VerbsDocument4 pagesPast Simple Test: A. Write The Past Forms of The Regular and Irregular VerbsFlorentina StefanNo ratings yet

- Degree Level Prelims Solved Question PaperDocument12 pagesDegree Level Prelims Solved Question PaperAnandhuBalanNo ratings yet

- Assignment: "My Greatest Ambition"Document6 pagesAssignment: "My Greatest Ambition"Muskan FatimaNo ratings yet

- 2022 2023 First Periodical Test in English 4Document8 pages2022 2023 First Periodical Test in English 4Bibiano Ricafranca, Jr.100% (1)

- Słowotwórstwo - Ćwiczenia Repetytorium Express PublishingDocument34 pagesSłowotwórstwo - Ćwiczenia Repetytorium Express PublishingzuznixyzNo ratings yet

- Lacan Avec Peirce: A Semeiotic Approach To Lacanian ThoughtDocument117 pagesLacan Avec Peirce: A Semeiotic Approach To Lacanian ThoughtAndrew Lee YounkinsNo ratings yet

- Critical Thinking in An Efl Classroom at Rio de JaneiroDocument4 pagesCritical Thinking in An Efl Classroom at Rio de JaneiroAmanda OliveiraNo ratings yet

- TriominoesDocument4 pagesTriominoesAntwain UtleyNo ratings yet

- Checklist Literary Style ElementsDocument2 pagesChecklist Literary Style ElementsBulf Adela MihaelaNo ratings yet

- OutlineDocument35 pagesOutlineShanaNo ratings yet

- Exam's AnswerDocument4 pagesExam's AnswerMatilde MarzocchiNo ratings yet

- Depth of Reflection: 1 PT 2 Pts 3 Pts 4 PtsDocument1 pageDepth of Reflection: 1 PT 2 Pts 3 Pts 4 PtsSarce PaoloNo ratings yet

- R1 ADocument20 pagesR1 AFarid AmirzaiNo ratings yet

- Film and TV SitcomsDocument10 pagesFilm and TV SitcomsLisa CarpitelliNo ratings yet

- Đáp Án Đề Thi HSG 9Document2 pagesĐáp Án Đề Thi HSG 9Thu TrangNo ratings yet

- Unit 19-20Document10 pagesUnit 19-20Wulan AnggreaniNo ratings yet