Structure of

Keratin

� Introduction

Fibrous (structural) proteins.Individual molecules

combine to form insoluble structures

Keratins are the molecular basis for hair, nails, wool,

feathers, beaks, claws and horns.

It is also found in the cytoskeleton of cells. Keratin

clusters are found on chromosomes 12 and 17. α-keratin

is a fibrous structural protein, meaning it is made up of

amino acids that form a repeating secondary structure.

The secondary structure of α-keratin is very similar to

that of a traditional protein α-helix and forms a coiled

structure

Due to its tightly wound structure, it can function as one

of the strongest biological materials and has various

functions in mammals, from predatory claws to hair for

warmth.

α-keratin is synthesized through protein biosynthesis,

utilizing transcription and translation, but as the cell

�� α-keratin is a polypeptide chain, typically high in alanine,

leucine, arginine, and cysteine, that forms a right-handed

α-helix.

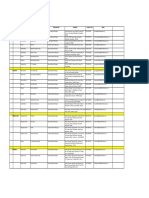

Two of these polypeptide chains twist together to form a

left-handed helical structure known as a coiled coil.

These coiled coil dimers, approximately 45 nm long, are

bonded together with disulfide bonds, utilizing the many

cysteine amino acids found in α-keratins.

The dimers then align, their terminal bonding with the

terminal of other dimers, and two of these new chains

bond length-wise, all through disulfide bonds, to form a

protofilament.

Two protofilaments aggregate to form a protofibril, and

four protofibrils polymerize to form the intermediate

filament (IF).

The IF is the basic subunit of α-keratins. These IFs are

able to condense into a super-coil formation of about 7

nm in diameter, and can be type I, acidic, or type II, basic.

The IFs are finally embedded in a keratin matrix that

�Characterization

Alpha-keratins proteins can be one of two types: type I or type II.

There are 54 keratin genes in humans, 28 of which code for type

I, and 26 for type II.

Type I proteins are acidic, meaning they contain more acidic

amino acids, such as aspartic acid, while type II proteins are

basic, meaning they contain more basic amino acids, such as

lysine.

This differentiation is especially important in alpha-keratins

because in the synthesis of its sub-unit dimer, the coiled coil, one

protein coil must be type I, while the other must be type II.

Even within type I and II, there are acidic and basic keratins that

are particularly complementary within each organism.

For example, in human skin, K5, a type II alpha keratin, pairs

primarily with K14, a type I alpha-keratin, to form the alpha-

keratin complex of the epidermis layer of cells in the skin.

�Properties

The property of most biological importance of alpha-

keratin is its structural stability.

When exposed to mechanical stress, α-keratin structures

can retain their shape and therefore can protect what

they surround.

Under high tension, alpha-keratin can even change into

beta-keratin, a stronger keratin formation that has a

secondary structure of beta-pleated sheets.

Alpha-keratin tissues also show signs of viscoelasticity,

allowing them to both be able to stretch and absorb

impact to a degree, though they are not impervious to

fracture.

Alpha-keratin strength is also affected by water content

in the intermediate filament matrix; higher water

content decreases the strength and stiffness of the

keratin cell due to their effect on the various hydrogen

� Hard alpha-keratins, such as those found in nails, have a

higher cysteine content in their primary structure.

This causes an increase in disulfide bonds that are able to

stabilize the keratin structure, allowing it to resist a

higher level of force before fracture.

On the other hand, soft alpha-keratins, such as ones

found in the skin, contain a comparatively smaller amount

of disulfide bonds, making their structure more flexible.

�Thank You