0% found this document useful (0 votes)

23 views70 pagesAMT Airframe

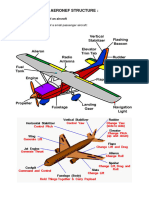

The document provides an overview of aircraft structures, detailing the evolution of airframe components from early designs to modern aircraft, emphasizing the importance of materials and structural integrity. It discusses the major components of an airframe, including the fuselage, wings, and landing gear, as well as the types of stresses these components must withstand. The document also explains the construction methods, such as truss and monocoque designs, and highlights the significance of stress analysis in ensuring the safety and performance of aircraft.

Uploaded by

Chouaib Ben BoubakerCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as PPT, PDF, TXT or read online on Scribd

0% found this document useful (0 votes)

23 views70 pagesAMT Airframe

The document provides an overview of aircraft structures, detailing the evolution of airframe components from early designs to modern aircraft, emphasizing the importance of materials and structural integrity. It discusses the major components of an airframe, including the fuselage, wings, and landing gear, as well as the types of stresses these components must withstand. The document also explains the construction methods, such as truss and monocoque designs, and highlights the significance of stress analysis in ensuring the safety and performance of aircraft.

Uploaded by

Chouaib Ben BoubakerCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as PPT, PDF, TXT or read online on Scribd