Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Streetcar

Uploaded by

None None NoneCopyright

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentC I T Y O F M I A M I I N I T I A L S T R E E T C A R C O R R I D O R F E A S I B I L I T Y S T U D Y Executive Summary

April 2005

ES-1

CI TY OF MI AMI I NI TI AL

STREETCAR CORRI DOR

FEASI BI LI TY STUDY

FI NAL REPORTAPRI L 2005

EXECUTI VE SUMMARY

Between 1925 and 1928, more than 11 million passengers

per year boarded trolley cars in Miami.

1

Trolleys, or

streetcars, were an integral part of the Citys growth

and development early in the 20

th

century. The Miami

system of streetcars stopped operating in November

1940. Now, 65 years later, the City of Miami (the City) is

evaluating the reintroduction of streetcar service with a

modern technology counterpart. With this new transit

service, the City seeks to provide its residents,

businesses, and visitors with an attractive, convenient,

comfortable urban mode of transit that is less expensive

compared to light rail.

The proposed 6.75 mile (10.86 km) streetcar service

would provide improved transit connections between

Downtown Miami and the redeveloping areas of

Wynwood/Edgewater, Midtown Miami, the Miami Design

District and the Buena Vista East Historic District. The

streetcar is electrically powered and would run, at

grade, on rail, within the roadway. The service is

intended to link with Metrorail and Metromover as well

as with other planned transportation systems. It would

also guide and enhance new investment opportunities for

commerce, housing, the arts, cultural attractions and

recreation, bringing additional jobs and tax revenues to

the City.

Study Context and Purpose

Miami is undergoing spectacular growth. Since 2001, the

City has witnessed a 10% increase in population.

Estimates suggest that by the end of this decade,

Miamis population may expand as much as 30%. This

surge is a stark contrast to the 1% growth experienced in

the 1990s and the 7% total seen from 1970-2000. The

Citys renaissance includes significant new commercial

and residential investments, new residents living in

Downtown Miami, new major public facilities and parks,

and numerous capital improvement projects now

breaking ground. Miamis urban intensification, in part,

reflects a national pattern, wherein young people and

empty nest baby boomers are seeking an urban

lifestyle and avoiding the daily commute on increasingly

congested highways. There is more at work here,

however, than national demographic patterns. The

renaissance underway in Miami is also being fueled by its

stunning physical setting, its rising economic strength

and by its reputation as an international gateway.

These positive trends bring with them a question which

Miami must prepare to face: will the existing

transportation system be able to support and sustain a

much denser and less automobile dependent urban

Miami? Might streetcars, used so successfully in the

improvement of other downtowns, be an ingredient in a

successful strategy for the world-class downtown that

Miami seeks to become?

The existing downtown transportation system of transit

and streets is no longer adequate to support the

redevelopment growth. The street network is fixed in its

number of lanes for carrying automobiles. The existing

transit system consists of buses operating on those same

streets and two fixed guideway systems, the Metrorail

and Metromover, that are unsuited to the task of

improving circulation for a multiplicity of short trips

within the study area and do not reach many of the

areas now experiencing large-scale redevelopment. All

development, even its most urban forms, requires

convenient access and circulation. So, how can Miamis

dramatic transformation be effectively supported and

sustained; how will all those additional residents,

workers and visitors move around?

The subject of this study is not how the Miami-Dade

urbanized area will improve its transportation system to

meet regional needs, address congestion and improve air

quality. The focus here is local, at the district or

neighborhood scale. How will everyday trips, to the

grocery store, to a lunch meeting, or to the

entertainment, cultural and dining destinations in

Downtown Miami be made for tens of thousands of new

residents, workers and visitors? If the answer to that

question is by using their cars, the result will not be

sustainable, livable urbanism. Excellent transit service to

circulate people within Downtown Miami, aside from

whatever is done to connect the downtown to the

surrounding suburbs, is very important.

The City of Miami Initial Streetcar Corridor Feasibility

Study, Final Report, April 2005, was conducted for a

study area bounded by the Miami River, Miami Avenue

(including Government Center), NE 79

th

Street and

Biscayne Boulevard and found the following:

The proposed project can effectively provide

attractive, convenient and reliable transit

connections between Downtown Miami and

redeveloping areas.

Streetcars are the most appropriate and readily

available transit technology for the needs of the

study area.

The proposed project can efficiently increase

the capacity and use of the Citys local and

regional public transportation system through

integration with the existing and proposed

enhanced Miami-Dade Transit (MDT) system.

The proposed project can guide and sustain

economic development and support a sustainable

pattern of urban land use activities.

The proposed project can feasibly operate on

segments, of selected roadway corridors without

adversely impacting traffic flow, parking

facilities, business operations, and other corridor

characteristics.

The proposed project is financially feasible and

can be implemented with existing and new

revenue sources.

Study Funding and Management

This initial feasibility study was funded by the City of

Miamis share of the Miami-Dade County Peoples

Transportation Plan (PTP) transportation half-cent surtax

of which twenty-percent of the annual collections

provided to the City must be encumbered for transit

Executive Summary

1

Biscayne Bay Trolleys: Street Railways of the Miami Area, Edward Ridolph, Harold E. Cox pub-

lisher, 80 Virginia Terrace, Forty Fort, PA 18704, 1981., p. 51.

C I T Y O F M I A M I I N I T I A L S T R E E T C A R C O R R I D O R F E A S I B I L I T Y S T U D Y Executive Summary

April 2005

ES-2

purposes or revert back to Miami-Dade County for

redistribution.

This study was managed by staff of the Capital

Improvement Program and Transportation Department,

Office of the City Manager, for the City of Miami.

What is Streetcar Transit?

Streetcars are a mode of public transit that operates

along a fixed rail guideway that is embedded within the

surface of the roadway. While streetcars cannot deviate

from the path of the guideway, the operator of the

streetcar drives the vehicle, accelerating and braking

to move along with traffic that may operate in the same

lane as the streetcar. Streetcars are related to light rail

transit; the difference is that streetcars are smaller,

lighter, less expensive, and usually run in traffic, rather

than in their own exclusive right-of-way. Powered by

quiet electric motors, these vehicles use an overhead

arm called a pantograph to collect power from an

electrified wire that is suspended approximately 20 feet

(6.10 meters) over the lane in which the streetcar runs.

Streetcars can look contemporary or vintage with many

body styles available and can be outfitted with numerous

features.

Study Process

This initial feasibility study was conducted in two parts

from February 2004 to April 2005. Part I of the Study

(Concept Plan) included the following tasks:

Evaluated 12 corridor segments for physical and

economic feasibility.

Conducted initial coordination and information

meetings with several project area stakeholders

to determine the compatibility and effectiveness

of a proposed streetcar project with respect to

governmental agency and district plans.

Developed criteria for selection of a Phase I

streetcar project.

Applied the criteria to the alternative corridors

examined.

Identified any fatally flawed corridors (or

corridor segments where physical, environmental

or policy constraints would prohibit streetcar

construction and use) in the study area.

Identified corridors where streetcars would

enhance and reinforce the objectives of

redevelopment and revitalization efforts in the

City of Miami.

Developed a conceptual route with station

locations for a series of streetcar lines which

could serve major destinations, connect areas

undergoing redevelopment, and provide access

to other areas to improve their viability for

redevelopment.

Part II of the Study (Planning, Analysis &

Implementation) built on the Part I research; it

addressed:

Refinement of the conceptual route alignment to

a Phase 1 recommended streetcar alignment.

Coordination of the conceptual alignment with

the proposed Bay Link project on the Downtown

Miami portion of the study area south of

Interstate 395.

Identification of the requirements for a

maintenance and operations facility.

Engineering and operational issues involved with

the proposed streetcar line crossing the Florida

East Coast Railway (FEC) in multiple locations

along the alignment, including securing the

cooperation of FEC for further development of

the project.

Preliminary capital and operating cost estimates

for the initial phase of the project.

Detailed analysis of the land use and economic

development scenario throughout the study

area.

Potential environmental analysis requirements.

Best practices in the revision of land use plans

and ordinances in other cities which have

developed streetcar systems.

Options for financing construction and operation

of the project and options for implementation

and management of the service on an ongoing

basis.

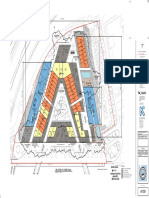

Initial Project Phase Recommendation

The study concluded that streetcar service is feasible

and will be a key component in Miamis transportation

system and redevelopment strategies. A variety of

analytical measures were used to evaluate the various

Phase I corridors. Having applied these criteria and

analyzed the 12 potential corridors, an initial Phase 1

alignment of a Miami streetcar system is recommended

(see Figure ES.1). This system provides the best

combination of physical compatibility, economic

development opportunity, and integration with existing

and planned transportation projects in the study area.

The recommended initial Phase I for streetcar service

connects Downtown Miami to the Miami Design District

and Buena Vista East Historic District, primarily via NE

2

nd

Avenue (Figure ES.1). The recommended alignment

will provide streetcar service in both directions, with

stops located approximately every two to five blocks.

While streetcar service will be feasible and provide many

advantages for the entire NE 2

nd

Avenue corridor, and

while there are multiple possibilities for extending

streetcar service to other city neighborhoods, it is

critical to begin with the most compelling phase of what

can become a system. That is, the projects success is

dependent on beginning with that section of the system

that has the greatest intensity of economic

development, projected ridership, financing capability,

and connectivity with the existing Metrorail and

Metromover and Miami-Dade Transit bus systems, as well

as with additions and enhancements to the transit

system now in the planning process such as the proposed

Bay Link project.

This alignment effectively connects existing urban

development in the downtown core with major

destinations such as the Government Center, Miami-Dade

College, Performing Arts Center, the Entertainment

Executive Summary

Photosimulation of proposed streetcar - NE 1st Avenue Photosimulation of proposed streetcar - NE 2nd Avenue

C I T Y O F M I A M I I N I T I A L S T R E E T C A R C O R R I D O R F E A S I B I L I T Y S T U D Y

Figure ES.1 - Phase 1 Recommended Streetcar Project

Study Area

Recommended Phase I Streetcar Alignment

Recommended Phase I Streetcar Station/Stop Locations

Midtown Miami

Miami Design District

Miami Downtown Development Authority

LEGEND

Metromover

Metrorail

ES-3

395

INTERSTATE

95

INTERSTATE

1

7 441

1

195

INTERSTATE

F

l

a

g

l

e

r

S

t

.

S

W

1

s

t

S

t

.

N

W

1

s

t

S

t

.

N

W

5

t

h

S

t

.

N

W

1

1

t

h

S

t

.

N

W

1

4

t

h

S

t

.

N

W

2

0

t

h

S

t

.

N

W

2

9

t

h

S

t

.

N

W

3

6

t

h

S

t

.

N

W

4

0

t

h

S

t

.

N

W

4

6

t

h

S

t

.

N

W

5

4

t

h

S

t

.

N

W

6

2

n

d

S

t

.

S. Miami Av.

Brickell Av.

NE 1st Av.

NW 1st Av.

NE 2nd Av.

Biscayne Blvd.

NW 2nd Av.

FEC Corridor

NW 1st Av.

NE 2nd Av.

Biscayne Blvd.

NW 2nd Av.

N. Miami Av.

NW 3rd Av.

NW 5th Av.

NW 7th Av.

NW 8th Av.

NW 10th Av.

NW 11th Av.

J

u

l

i

a

T

u

t

t

l

e

C

s

w

y

.

V

e

n

e

t

i

a

n

C

s

w

y

.

G

e

n

.

D

o

u

g

l

a

s

M

a

c

A

r

t

h

u

r

C

s

w

y

.

P

o

r

t

B

l

v

d

.

95

INTERSTATE

N

O

T

T

O

S

C

A

L

E

CI TY OF

MIAMI

N

W

7

1

s

t

S

t

.

N

E

7

9

t

h

S

t

.

Biscayne Blvd.

NE 2nd Av.

N Miami Av.

N

W

3

9

t

h

S

t

.

N

E

1

9

t

h

S

t

.

N

E

1

7

t

h

S

t

.

N

E

1

5

t

h

S

t

.

N

E

1

3

t

h

S

t

.

N

E

1

2

t

h

S

t

.

N

E

1

1

t

h

T

e

r

r

.

N

W

1

0

t

h

S

t

.

N

W

9

t

h

S

t

.

N

W

8

t

h

S

t

.

N

W

6

t

h

S

t

.

N

W

4

t

h

S

t

.

N

W

3

r

d

S

t

.

N

E

2

n

d

S

t

.

NE 1st Av.

N. Miami Av.

NE 2nd Av.

Downtown

Miami Little

Haiti

Miami

Design District

Midtown Miami

C I T Y O F M I A M I I N I T I A L S T R E E T C A R C O R R I D O R F E A S I B I L I T Y S T U D Y Executive Summary

April 2005

ES-4

District, the planned Museum Park, Midtown Miami and

the Miami Design District and Buena Vista East Historic

District. It also links these destinations with a very large

increment of recently completed, planned and

anticipated development within mile of the

alignment, as much as 2.64 million square feet (0.245

million square meters) of new office and retail

construction and over 14,750 new residential units (see

Figure ES.2).

The recommended alignment is fully integrated with the

proposed Bay Link streetcar line being planned to

connect Downtown Miami (see Figure ES.3) with Miami

Beach to provide enhanced circulation within the

downtown areas of both cities. By seamlessly expanding

the possible trips which can utilize streetcars, the

effectiveness and efficiency of both projects will be

improved. The integration of these two projects will also

allow the use of a joint maintenance and operations

facility, again with cost and efficiency benefits.

The proposed Miami Streetcar project is configured to

complement transit service which might utilize the

current Florida East Coast (FEC) Railway. Several

locations along the recommended streetcar alignment

afford the opportunity for shared stops to connect with

this potential future service. However, using this FEC

right-of-way for the streetcar line itself is not feasible

since streetcars are an urban transit mode and need to

be placed in pedestrian-oriented areas and since

streetcars are incompatible for operation together with

the existing freight rail operations and potential

commuter rail on the FEC Railway track that accesses

the Port of Miami and Downtown Miami. As design of the

proposed Miami Streetcar project proceeds, however,

consideration should be given to the most westerly

section of the downtown streetcar loop, examining how

it will connect with a downtown terminus for commuter

rail, passenger rail and other transit services.

Project Components

The initial Phase 1 of the Miami Streetcar project

includes a 6.75 miles (10.86 km) round trip loop of

trackway of which 3.15 miles (5.07 km) is single track

where the streetcar runs one way on a given section of

street and 1.8 miles (2.90 km) of double track where the

streetcar runs in both directions in the same section of

street. Approximately 33 stops will be provided along the

route. The project will operate with an initial fleet of

eight vehicles. Of this infrastructure, 2.42 miles (3.89

km) of the single track, 0.21 miles (0.34 km) of the

double track and six of the stops will be potentially

shared by the proposed Bay Link streetcar line in

Downtown Miami. Other project elements, including the

vehicle and operations maintenance facility and electric

power substations, may also be shared by Bay Link.

It is recommended that Miami use modern European

tram style vehicles for this project. In some contexts,

like Tampas Ybor City Historic District, a vintage style

vehicle is appropriate. Miami is by contrast a modern

city, and this project is envisioned as equally modern.

Thus the characteristics of modern streetcars (larger

passenger capacity, large doors for quick boarding and

exiting, compliance with the Americans with Disabilities

Act) are best suited for this application. The Bay Link

streetcar project is designed to be compatible with the

same modern, Inekon/Portland-type vehicle proposed for

the Miami Streetcar project.

The preliminary estimated construction and system costs

for this initial Phase I are $132,255,000 (year 2004 US

dollars) which includes track, roadway and utility costs,

a maintenance and operations facility, vehicles, Florida

East Coast Railway crossings, design, construction and

project contingencies. Annual operating cost, assuming

streetcar arrival at any given stop (headways) every 10

minutes, is estimated at $3,500,000 per year (year 2004

US dollars). Preliminary streetcar ridership projections

estimate 3,000 at opening year and potentially 8,100

riders per day in year 2025 depending upon several

variables which are unknown at this feasibility stage,

such as; fare structure, service frequency, operating

speed and corridor redevelopment. Environmental

requirements facing the project at this feasibility stage

appear to be minimal and are not likely to pose a

significant hurdle for project advancement. The project

is financially feasible to construct and operate; several

possible scenarios for funding capital and operating costs

have been developed.

There are a number of options for project

implementation, including the formation of a new

Authority similar to the Miami Downtown Development

Authority (DDA) or the Miami Parking Authority. The

project could also be advanced through a public-private

partnership wherein the project would be owned by the

City of Miami, but developed and managed through a

nonprofit corporation similar to the partnership formed

in Portland, Oregon. In any scenario, the active

cooperation of Miami-Dade County, the Board of County

Executive Summary

Portland Streetcar Rail Construction

Track,

Roadway

and Utility

Costs

FEC Rail

Crossings

Vehicles

Design/

Construction

Maintenance

Facility

Contingency

$132,255,000

(Year 2004 Dollars)

Phase 1 Streetcar Project

Construction and System Costs

Phase 1 Streetcar Daily Ridership

0

2,000

4,000

6,000

8,000

10,000

Opening 2025

Base Enhanced Vision

Opening

2008

Year

2025

C I T Y O F M I A M I I N I T I A L S T R E E T C A R C O R R I D O R F E A S I B I L I T Y S T U D Y

Figure ES.2 - Study Area Development

As of April 19, 2004

LEGEND

Study Area

Omni Community Redevelopment Agency (Omni CRA)

Southeast Overtown Park West Community Redevelopment Agency (SEOPW CRA)

Miami Downtown Development Authority

Special Districts (Shown in various colors)

OMNI CRA

Government Center

Miami-Dade College

Miami Arena

NW 7th Street Spine

Crosswinds Transit Village

Historic Overtown

Folklife Village

West Overtown

Big Time Productions

Overtown Business Corridor

3rd Avenue District

Onyx

Blue

Lofts

Rosabella Lofts

Avant

Tuttle

Bayside Marketplace

American Airlines Arena

Museum Park

Mist

Biscayne Bay Special Area Plan

10 Museum Park

Performing Arts Center

Omni Center

14th Street Corridor

Bay Park Plaza

Quantum on the Bay

Park Lofts

Miami Childrens

Museum

Parrot Jungle

Island Gardens

SEOPW

CRA

One Miami

Dupont Plaza

MET Miami

Bayfront Park

Flagler St.Corridor

50 Biscayne

Columbus Office

Tower

Everglades

on the Bay

ES-5

395

INTERSTATE

95

INTERSTATE

1

7 441

1

195

INTERSTATE

F

l

a

g

l

e

r

S

t

.

S

W

1

s

t

S

t

.

N

W

1

s

t

S

t

.

N

W

5

t

h

S

t

.

N

W

1

1

t

h

S

t

.

N

W

1

4

t

h

S

t

.

N

W

2

0

t

h

S

t

.

N

W

2

9

t

h

S

t

.

N

W

3

6

t

h

S

t

.

N

W

4

0

t

h

S

t

.

N

W

4

6

t

h

S

t

.

N

W

5

4

t

h

S

t

.

N

W

6

2

n

d

S

t

.

S. Miami Av.

Brickell Av.

NE 1st Av.

NW 1st Av.

NE 2nd Av.

Biscayne Blvd.

NW 2nd Av.

FEC Corridor

NW 1st Av.

NE 2nd Av.

Biscayne Blvd.

NW 2nd Av.

N. Miami Av.

NW 3rd Av.

NW 5th Av.

NW 7th Av.

NW 8th Av.

NW 10th Av.

NW 11th Av.

J

u

l

i

a

T

u

t

t

l

e

C

s

w

y

.

V

e

n

e

t

i

a

n

C

s

w

y

.

G

e

n

.

D

o

u

g

l

a

s

M

a

c

A

r

t

h

u

r

C

s

w

y

.

P

o

r

t

B

l

v

d

.

95

INTERSTATE

N

O

T

T

O

S

C

A

L

E

CI TY OF

MIAMI

N

W

7

1

s

t

S

t

.

N

E

7

9

t

h

S

t

.

Biscayne Blvd.

NE 2nd Av.

N Miami Av.

N

W

3

9

t

h

S

t

.

N

E

1

9

t

h

S

t

.

N

E

1

7

t

h

S

t

.

N

E

1

5

t

h

S

t

.

N

E

1

3

t

h

S

t

.

N

E

1

2

t

h

S

t

.

N

E

1

1

t

h

T

e

r

r

.

N

W

1

0

t

h

S

t

.

N

W

9

t

h

S

t

.

N

W

8

t

h

S

t

.

N

W

6

t

h

S

t

.

N

W

4

t

h

S

t

.

N

W

3

r

d

S

t

.

N

E

2

n

d

S

t

.

NE 1st Av.

N. Miami Av.

NE 2nd Av.

Little

Haiti

Upper

East Side

Wynwood/

Edgewater

Entertainment

District

Overtown

Buena

Vista

East

Buena

Vista Heights

ark W Park West

Little

Haiti

Design District

Miami

Design District

Downtown

Miami

Midtown Miami

Source: Department of Planning & Zoning, City of Miami (April 19, 2004)

C I T Y O F M I A M I I N I T I A L S T R E E T C A R C O R R I D O R F E A S I B I L I T Y S T U D Y

Figure ES.3 - Downtown Streetcar Alignment Shared with Proposed

Bay Link Streetcar

ES-6

Recommended Streetcar Alignment

Recommended Streetcar Station/Stop Locations

Metromover

Metromover Stop Locations

Metrorail

Metrorail Stop Locations

Bay Link (Proposed)

Bay Link (Optional Alignment)

Shared Alignment: Streetcar & Bay Link

LEGEND

NOTE: Segments shown as shared alignment indicate where both

Miami Streetcar and Proposed Bay Link will share the same track when

both systems are operational.

N

O

T

T

O

S

C

A

L

E

CI TY OF

MIAMI

Bay Link to

Miami Beach

Streetcar to Miami

Design District & Buena

Vista Historic District

395

INTERSTATE

1

N

E

1

7

t

h

S

t

.

N

E

1

5

t

h

S

t

.

N

E

1

3

t

h

S

t

.

N

E

1

2

t

h

S

t

.

N

E

1

1

t

h

T

e

r

r

.

N

E

1

0

t

h

S

t

.

N

W

9

t

h

S

t

.

N

W

8

t

h

S

t

.

N

W

6

t

h

S

t

.

N

W

4

t

h

S

t

.

N

W

3

r

d

S

t

.

N

E

2

n

d

S

t

.

F

l

a

g

l

e

r

S

t

.

S

W

1

s

t

S

t

.

N

W

1

s

t

S

t

.

N

W

5

t

h

S

t

.

N

W

1

1

t

h

S

t

.

N

W

1

4

t

h

S

t

.

S. Miami Av.

Brickell Av.

NE 1st Av.

NW 1st Av.

NE 2nd Av.

Biscayne Blvd.

NW 2nd Av.

V

e

n

e

t

i

a

n

C

s

w

y

.

G

e

n

.

D

o

u

g

l

a

s

M

a

c

A

r

t

h

u

r

C

s

w

y

.

P

o

r

t

B

l

v

d

.

NW 1st Ct.

NW 1st Av.

C I T Y O F M I A M I I N I T I A L S T R E E T C A R C O R R I D O R F E A S I B I L I T Y S T U D Y Executive Summary

April 2005

ES-7

Commissioners, the Miami-Dade

Metropolitan Planning Organization,

Miami-Dade Transit, the Miami-Dade

Public Works Department, the

Citizens Independent Transportation

Trust and other entities will need to

be secured in order to build and

operate the project. Other public

agencies, including the Federal Transit

Administration and the Florida

Department of Transportation, will be

key to implementation. Property

owners and tenants along the

alignment must be fully informed and

enlisted as project supporters in order

to implement the project and ensure

success.

The Opportunity

Streetcar projects are being designed and built in a

growing number of North American cities. Few of these

locations possess the potential which Miami enjoys in the

project study area. The combination of factors is

formidable: an intense development boom and the

project financing possibilities resulting from this

economic momentum, great destinations like

Government Center, Miami-Dade College the new

Performing Arts Center and the planned Museum Park,

corridor that is functionally and physically ideal for this

form of transit, and a Miami-Dade County Transit system

that could serve the community better if a local

circulation component is provided. Based on this, the NE

2

nd

Avenue corridor is the place to begin in restoring this

critical component of urban life to Miami. As Figure ES.4

shows, there are many possibilities for future expansion

of streetcar service, once an initial phase is

implemented.

A streetcar project in this corridor will serve many

transportation purposes. It will allow choice riders to

make many short commute and non-commute trips by

means other than the automobile. The function and

reach of the Miami-Dade Transit rail and bus system will

be improved by circulating riders into adjacent areas. It

will improve the attractiveness and convenience of

Downtown Miami as a visitor destination by allowing

visitors convenient access to the various attractions.

More than these commendable transportation benefits,

the Miami Streetcar will have a powerful beneficial

effect on the location, form and sustainability of

development, redevelopment and conservation in the

neighborhoods it serves. The project will be a catalyst,

enhancing smart growth inland from the bayfront

properties, shaping the character of this development

into a more pedestrian friendly, transit supportive

environment.

Finally, the proposed Miami Streetcar will have great

symbolic and functional value, demonstrating that Miami

has the comprehensive multi-modal transportation

system expected in a world-class city.

This initial feasibility study has been the first step in

planning the Miami Streetcar project. The next steps

include consideration by the City of Miami Commission

for the adoption of the City of Miami Initial Streetcar

Corridor Feasibility Study, Final Report, April 2005;

authorization to the City Manager to begin initial

implementation of the Study recommendations providing

that the initial implementation will consist of

Alternatives Analysis to satisfy Federal Transit

Administration requirements for fund eligibility; and,

further, selection of a Design/Contractor team to

provide conceptual engineering is support of the

environmental approval process and financial support

services in the development of a detailed financial plan

Executive Summary

Photosimulation - Wolfson Campus Station

Portland, Oregon - Transit Oriented Development Along an Existing Streetcar Route

C I T Y O F M I A M I I N I T I A L S T R E E T C A R C O R R I D O R F E A S I B I L I T Y S T U D Y

Figure ES.4 - Potential Corridor Extensions

1/4 mile (10 minute) walk to streetcar

Recommended Phase I Streetcar Alignment

Recommended Phase I Streetcar Station/Stop Locations

Potential Service Extensions

LEGEND

N

O

T

T

O

S

C

A

L

E

CI TY OF

MIAMI

395

INTERSTATE

95

INTERSTATE

1

7 441

1

195

INTERSTATE

F

l

a

g

l

e

r

S

t

.

S

W

1

s

t

S

t

.

N

W

1

s

t

S

t

.

N

W

5

t

h

S

t

.

N

W

1

1

t

h

S

t

.

N

W

1

4

t

h

S

t

.

N

W

2

0

t

h

S

t

.

N

W

2

9

t

h

S

t

.

N

W

3

6

t

h

S

t

.

N

W

4

0

t

h

S

t

.

N

W

4

6

t

h

S

t

.

N

W

5

4

t

h

S

t

.

N

W

6

2

n

d

S

t

.

S. Miami Av.

Brickell Av.

NE 1st Av.

NW 1st Av.

NE 2nd Av.

Biscayne Blvd.

NW 2nd Av.

FEC Corridor

NW 1st Av.

NE 2nd Av.

Biscayne Blvd.

NW 2nd Av.

N. Miami Av.

NW 3rd Av.

NW 5th Av.

NW 7th Av.

NW 8th Av.

NW 10th Av.

NW 11th Av.

J

u

l

i

a

T

u

t

t

l

e

C

s

w

y

.

V

e

n

e

t

i

a

n

C

s

w

y

.

G

e

n

.

D

o

u

g

l

a

s

M

a

c

A

r

t

h

u

r

C

s

w

y

.

P

o

r

t

B

l

v

d

.

95

INTERSTATE

N

W

7

1

s

t

S

t

.

N

E

7

9

t

h

S

t

.

Biscayne Blvd.

N Miami Av.

N

W

3

9

t

h

S

t

.

N

E

1

9

t

h

S

t

.

N

E

1

7

t

h

S

t

.

N

E

1

5

t

h

S

t

.

N

E

1

3

t

h

S

t

.

N

E

1

2

t

h

S

t

.

N

E

1

1

t

h

T

e

r

r

.

N

E

1

0

t

h

S

t

.

N

W

9

t

h

S

t

.

N

W

8

t

h

S

t

.

N

W

6

t

h

S

t

.

N

W

4

t

h

S

t

.

N

W

3

r

d

S

t

.

N

E

2

n

d

S

t

.

NE 1st Av.

N. Miami Av.

NE 2nd Av.

F

l

a

g

l

e

r

S

t

.

395

INTERSTATE

95

INTERSTATE

1

7 441

1

F

l

a

g

l

e

r

S

t

.

S

W

1

s

t

S

t

.

N

W

1

s

t

S

t

.

N

W

5

t

h

S

t

.

N

W

1

1

t

h

S

t

.

N

W

1

4

t

h

S

t

.

N

W

2

0

t

h

S

t

.

N

W

2

9

t

h

S

t

.

N

W

3

6

t

h

S

t

.

N

W

4

0

t

h

S

t

.

N

W

4

6

t

h

S

t

.

N

W

5

4

t

h

S

t

.

N

W

6

2

n

d

S

t

.

S. Miami Av.

Brickell Av.

NE 1st Av.

NW 1st Av.

NE 2nd Av.

Biscayne Blvd.

NW 2nd Av.

FEC Corridor

NW 1st Av.

NE 2nd Av.

Biscayne Blvd.

NW 2nd Av.

N. Miami Av.

NW 3rd Av.

NW 5th Av.

NW 7th Av.

NW 8th Av.

NW 10th Av.

NW 11th Av.

95

INTERSTATE

N

W

7

1

s

t

S

t

.

N Miami Av.

N

W

3

9

t

h

S

t

.

N

E

1

9

t

h

S

t

.

N

E

1

7

t

h

S

t

.

N

E

1

5

t

h

S

t

.

N

E

1

3

t

h

S

t

.

N

E

1

2

t

h

S

t

N

E

1

1

t

h

T

e

N

E

1

0

t

h

S

t

.

N

W

9

t

h

S

t

.

N

W

8

t

h

S

t

.

N

W

6

t

h

S

t

.

N

W

4

t

h

S

t

.

N

W

3

r

d

S

t

.

N

E

2

n

d

S

t

.

NE 1st Av.

N. Miami Av.

NE 2nd Av.

F

l

a

g

l

e

r

S

t

.

To Miami

City Limit

To University

of Miami/

Jackson

(Allapattah)

To Overtown

To East/West

Little Havana

To

Brickell

ES-8

C I T Y O F M I A M I I N I T I A L S T R E E T C A R C O R R I D O R F E A S I B I L I T Y S T U D Y Executive Summary

April 2005

ES-9

for project delivery of which the award of the work and

agreement for project delivery of the Miami Streetcar

project is to be brought back for future City of Miami

Commission consideration and approval.

For additional information about the project, please

contact:

Lilia I Medina, AICP Assist. Transportation Coordinator

City of Miami, Office of the City Manager/Transportation

444 SW 2nd Ave, 10

th

Fl., Miami, FL 33130

Tel. (305) 416-1080

Fax (305) 416-1019

limedina@ci.miami.fl.us

http://www.ci.miami.fl.us

Frequently Asked Questions

Why does Miami need streetcar transit?

Up to August 2004, there were over 60 development

projects at various stages of construction, permitting or

planning within 1/4 mile of the alignment that the

streetcar is planned to operate, creating over 14,000

residential units and over 2.64 million square feet (0.245

million square meters) of office and retail development.

This intensification of urban life in core areas of Miami

requires a more urban transportation system. Because

most of the street network in this area is restricted from

expanding due to limited right-of-way or existing

development, the City must explore other non-

automobile options to accommodate the increasing

transportation needs of this fast growing area. The

streetcar will help relieve the daily use of automobiles

and the demand for parking for short trips within the

project study area.

Why cant Miami-Dade Transit just add more buses?

Miami-Dade Transit will be adding more buses as their

entire system expands over the next several years, but

these additional buses will not satisfy the need for

frequent and reliable circulation in the Downtown Miami

area. There are two key reasons why adding more buses

will not work as well as the streetcar to meet circulation

needs. First, the number of buses required to equal the

capacity of one streetcar makes buses more expensive to

operate and maintain. Second, examples show that

streetcars attract choice riders, people who otherwise

would not ride a bus, because of the convenience,

comfort, attractiveness and reliability of the streetcar

and thus, the streetcar increases the number of people

who will use transit.

Cant we just expand the existing Miami-Dade Transit

Metromover or Metrorail?

Yes. However, the elevated structure and platforms for

the Metromover and Metrorail make expanding these

transit systems more costly and time consuming options

than building the streetcar system. Also, these systems

are less accessible and less convenient for the short trips

that streetcars frequently serve.

What other North American cities are using this type

of modern streetcar transit?

The best examples of the modern streetcar system

proposed for Miami are in Portland, Oregon and Tacoma,

Washington. Other successful systems include Tampa,

Florida; Toronto, Canada; San Francisco, California; and

San Diego, California. Many more systems are in planning

or construction, including: Washington, D.C.; Seattle,

Washington; Atlanta, Georgia; and Winston-Salem, North

Carolina.

How is this different from the Coral Gables Trolley?

The City of Coral Gables, Florida Trolley is a rubber tire,

internal combustion mini-bus circulator with a vintage

exterior body style and interior appointments also

consistent with the vintage styling, such as wooden

bench seats. The proposed Miami Streetcar is a modern,

overhead electrically powered rail vehicle. In addition to

these external differences in size and appearance, the

mini-bus circulator also has major differences in cost,

passenger capacity, maintenance requirements and

effect on economic development. Bus circulators like the

Coral Gables Trolley service work very well in meeting

modest transit demands in lower-intensity areas; for a

more dense urban environment like Downtown Miami, a

higher-capacity solution is needed.

Can the streetcar run along the Florida East Coast

(FEC) Railway Corridor?

The streetcar vehicle does not meet the Federal Railroad

Administration crash worthiness requirements that would

allow it to operate on an active rail line such as the FEC

Railway Corridor. In addition, the overhead power supply

needs of the streetcar would also conflict with the

vertical clearance requirements that the FEC establishes

for overhead utilities. Although the proposed streetcar

could run on the same sized rail as the freight trains that

operate on the FEC Railway corridor, the foregoing

factors preclude the operation of streetcar on the FEC

Corridor. Most significantly, use of the FEC Railway

Corridor is incompatible with the streetcar project since

streetcars are an urban transit mode and need to be

placed in pedestrian-oriented areas.

How will streetcars operate in mixed traffic? Wont

this cause more traffic congestion?

The proposed streetcars will operate in a designated

lane shared with other traffic in essentially the same

manner that buses do today (buses will even be able to

Executive Summary

Portland, Oregonstreetcar in mixed traffic.

Portland, Oregonstreetcar passengers.

C I T Y O F M I A M I I N I T I A L S T R E E T C A R C O R R I D O R F E A S I B I L I T Y S T U D Y Executive Summary

April 2005

ES-10

use the streetcar stops, as shown in the photo). The

driver of the streetcar can accelerate and brake to move

along with traffic, but does not have to steer the vehicle

because it runs along the rails embedded in the roadway

surface. In addition, the driver will be provided with

traffic signal controls, such as signal pre-emption that

enables the streetcar to clear congested intersections

and maintain schedule during heavy traffic. Streetcars

will improve congestion because they can reduce the

need for additional buses and will reduce automobile

usage for short trips.

What impact will streetcars have on on-street parking?

On-street parking impacts will be minimal. Some existing

on-street parking spaces may be needed to construct the

loading platform at station stop locations. The size of

the loading platform is equal to about two or three

parking spaces for a single streetcar station stop such

that the loss of parking is minimal.

Will the rails in the pavement be unsafe for bicyclists

and pedestrians?

No. The typical concerns for bicyclists and pedestrians

around the in-pavement rails are electric shock by the

rail and wheel/foot entrapment in the pavement groove.

The steel rails in the pavement are not electrified. The

pavement groove that the streetcar wheel flange rides

into is +/- 2 inches wide and does not present an issue

for foot entrapment. The narrow groove does warrant

caution to be exercised by bicyclists riding parallel with

the track. There is potential for the front wheel of a

bicycle to slip into the groove that could cause

temporary loss of control. This issue is typically

addressed with appropriate warning signage and the

design of bicycle lanes to cross the tracks at an angle.

How much does streetcar transit cost compared to

other types of transit options?

The capital cost for the proposed Miami Streetcar would

fall between the costs of Bus Rapid Transit and Light Rail

Transit at approximately $26 million per mile (Capital)

and $110 per Revenue Service Hour (Operating) in year

2004 US dollars. It should be noted that the costs

associated with any type of transit project vary by the

size of the system, hours of operation and the

complexity of physical and environmental issues that

must be overcome to implement the system. Bus systems

generally cost more to operate on a per passenger basis

(since each bus carries fewer passengers per operator

compared to rail systems), and have higher capital

replacement costs, since the vehicles wear out much

faster than rail vehicles.

How will the streetcar system be funded?

The detailed financial plan for funding capital and

operating costs has not been fully defined at this initial

feasibility stage. While several possible scenarios are

feasible, it is anticipated that traditional state and

federal transit funding sources, as well as locally

generated funding sources will be used to fund the

project. A next step in project implementation is a

completed financial or business plan.

Will the overhead wires create visual clutter?

It is unlikely that overhead catenary wires would create

visual clutter. This single wire can be obscured by

landscaping and tree canopy along the roadway. In other

cities where the streetcar corridor is established with

buildings and landscaping, the overhead wires blend into

the streetscape, and are not obtrusive on the downtown

streetscape. Typically, the overhead power is supplied

by a single electrified wire, and involves much less

overhead hardware than is seen with electric trolleybus

systems or light rail transit.

How are the overhead wires affected by hurricane

force winds?

All of the streetcar infrastructure is subject to the

hurricane code requirements required for roadway

utilities and would be affected similarly to any recently

constructed above ground utility.

Executive Summary

Portland, Oregonstreetcar at a stop.

Portland, Oregonbus at streetcar stop.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Bomag BMP8500Service Manual CompleteDocument300 pagesBomag BMP8500Service Manual Completeampacparts80% (15)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- W28 WDRC Print Set - RevDocument33 pagesW28 WDRC Print Set - Revthe next miamiNo ratings yet

- PLN Site 19120001Document105 pagesPLN Site 19120001None None NoneNo ratings yet

- T H MorayOscTubeDocument9 pagesT H MorayOscTuberocism01100% (1)

- EX-2 Fuel Pump Timing Setting and AdjustmentDocument2 pagesEX-2 Fuel Pump Timing Setting and AdjustmentAayush Agrawal100% (1)

- I-195 CPS Workshop Exhibits For Upload1Document7 pagesI-195 CPS Workshop Exhibits For Upload1None None NoneNo ratings yet

- Attachment 13468 89 112Document24 pagesAttachment 13468 89 112None None NoneNo ratings yet

- Southside PPP Presentation - RedactedDocument15 pagesSouthside PPP Presentation - RedactedNone None NoneNo ratings yet

- PlansDocument41 pagesPlansNone None NoneNo ratings yet

- 1420 S. Miami AvenueDocument57 pages1420 S. Miami AvenueNone None NoneNo ratings yet

- HPB19-0366 Plans 2019-12-16 HPB 1ST SubmittalDocument51 pagesHPB19-0366 Plans 2019-12-16 HPB 1ST SubmittalNone None None100% (1)

- City of Miami Planning and Zoning Department Udrb Application FormDocument22 pagesCity of Miami Planning and Zoning Department Udrb Application FormNone None NoneNo ratings yet

- 12.30.19 - Final PB Submittal Feb 2020 - Letter of IntentDocument8 pages12.30.19 - Final PB Submittal Feb 2020 - Letter of IntentNone None NoneNo ratings yet

- Agenda CompressedDocument706 pagesAgenda CompressedNone None NoneNo ratings yet

- WynwoodhausDocument34 pagesWynwoodhausNone None None100% (1)

- Attachment 13314 3 9Document7 pagesAttachment 13314 3 9None None NoneNo ratings yet

- Miami World TowersDocument43 pagesMiami World TowersNone None NoneNo ratings yet

- 12.30.19 - Final PB Submittal Feb 2020 - Arch. Landscape PlansDocument62 pages12.30.19 - Final PB Submittal Feb 2020 - Arch. Landscape PlansNone None None100% (1)

- Proposed Project 2Document21 pagesProposed Project 2None None NoneNo ratings yet

- LTC 045-2020 Miami-Dade County Beach Corridor Rapid Transit Project Development and Environment Study - CompressedDocument4 pagesLTC 045-2020 Miami-Dade County Beach Corridor Rapid Transit Project Development and Environment Study - CompressedNone None NoneNo ratings yet

- PLN Site 19120003Document65 pagesPLN Site 19120003None None NoneNo ratings yet

- A107 Level r1 Retail CommentedDocument1 pageA107 Level r1 Retail CommentedNone None NoneNo ratings yet

- Riverparc PlansDocument15 pagesRiverparc PlansNone None NoneNo ratings yet

- PLN Site 19120002Document96 pagesPLN Site 19120002None None None100% (1)

- Proposed ProjectDocument36 pagesProposed ProjectNone None None100% (1)

- Supplemental Documents 2-1-17Document17 pagesSupplemental Documents 2-1-17None None NoneNo ratings yet

- A109 Level r2 RetailDocument1 pageA109 Level r2 RetailNone None NoneNo ratings yet

- 2020 ULI Hines Student Competition Brief FinalDocument31 pages2020 ULI Hines Student Competition Brief FinalNone None NoneNo ratings yet

- Attachment 13062Document70 pagesAttachment 13062None None NoneNo ratings yet

- Existing Condition PlansDocument36 pagesExisting Condition PlansNone None NoneNo ratings yet

- Application DocumentsDocument65 pagesApplication DocumentsNone None NoneNo ratings yet

- SMART Plan Beach Corridor Presentation - CITT 12.18.2019Document40 pagesSMART Plan Beach Corridor Presentation - CITT 12.18.2019None None None100% (2)

- Dorsey - Letter of IntentDocument6 pagesDorsey - Letter of IntentNone None NoneNo ratings yet

- 22 Fall Spring 2004 PDFDocument164 pages22 Fall Spring 2004 PDFcombatps1No ratings yet

- ME460 Exam No. 2: NameDocument1 pageME460 Exam No. 2: NameSayyadh Rahamath BabaNo ratings yet

- Acid Plan in General Physics 1Document5 pagesAcid Plan in General Physics 1Edralyn PamaniNo ratings yet

- Lecture08 160425Document32 pagesLecture08 160425Anonymous 3G7tikAAdNo ratings yet

- Tune Up Spark Plug GappingDocument26 pagesTune Up Spark Plug GappingSelazinap LptNo ratings yet

- Requirements of EN 1838: Illuminance of 5 LX For Safety EquipmentDocument2 pagesRequirements of EN 1838: Illuminance of 5 LX For Safety EquipmenttestonsanNo ratings yet

- TESSCO Grounding Lightning at A GlanceDocument7 pagesTESSCO Grounding Lightning at A GlanceRepsaj NamilosNo ratings yet

- DS25A - (1967) Gas Chromatographic Data CompilationDocument306 pagesDS25A - (1967) Gas Chromatographic Data CompilationJacques StrappeNo ratings yet

- Man - Maxthermo - Mc49 - EngDocument8 pagesMan - Maxthermo - Mc49 - EngCsaba VargaNo ratings yet

- Resolver Vs EncoderDocument7 pagesResolver Vs EncoderAmirtha swamy.nNo ratings yet

- Register of Licences and Permits For Electric Power Undertakings PDFDocument20 pagesRegister of Licences and Permits For Electric Power Undertakings PDFNyasclemNo ratings yet

- Type 298 PV100 Medium Voltage IEC Switch Gear and Motor Control Centres 0210Document36 pagesType 298 PV100 Medium Voltage IEC Switch Gear and Motor Control Centres 0210Ryan JayNo ratings yet

- SMA FLX InstallationGuide-XXDocument248 pagesSMA FLX InstallationGuide-XXAnonymous smdEgZN2IeNo ratings yet

- New Chapter 6 Areva Transformer Differential ProtectionDocument54 pagesNew Chapter 6 Areva Transformer Differential ProtectionTaha Mohammed83% (6)

- Illiterure - Review & Quantetive Data 2Document7 pagesIlliterure - Review & Quantetive Data 2Redowan A.M.RNo ratings yet

- Techno-Commercial Proposal: Rooftop Solar Power Plant - 100 KW NTPC LimitedDocument11 pagesTechno-Commercial Proposal: Rooftop Solar Power Plant - 100 KW NTPC LimitedAmit VijayvargiNo ratings yet

- Engine: HMK 102 Energy Workshop ManualDocument20 pagesEngine: HMK 102 Energy Workshop ManualJonathan WENDTNo ratings yet

- QSL9 G91Document2 pagesQSL9 G91Obdvietnam ServiceNo ratings yet

- E 312 06 PDFDocument8 pagesE 312 06 PDFGia Minh Tieu TuNo ratings yet

- Semilab Technologies For 450mm Wafer MetrologyDocument0 pagesSemilab Technologies For 450mm Wafer Metrologyrnm2007No ratings yet

- Scanning Electron MicroscopeDocument6 pagesScanning Electron MicroscopeRaza AliNo ratings yet

- Hyosung Sf50 Prima 2007 Part CatalogueDocument76 pagesHyosung Sf50 Prima 2007 Part CatalogueRobert 70% (1)

- The Initial Stall in Span Wise DirectionDocument8 pagesThe Initial Stall in Span Wise DirectionpareshnathNo ratings yet

- PC1 532Document147 pagesPC1 532bharatsehgal00@gmail.comNo ratings yet

- IB Physics Topic 2Document18 pagesIB Physics Topic 2wee100% (1)

- Engine Kontrol 1Document35 pagesEngine Kontrol 1imat ruhimatNo ratings yet

- Inorgchem - D-Block Elements: PropertiesDocument8 pagesInorgchem - D-Block Elements: PropertiesHasantha PereraNo ratings yet