Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Johns Hopkins University Press

Uploaded by

mlindenberger25Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Johns Hopkins University Press

Uploaded by

mlindenberger25Copyright:

Available Formats

Reflections on the Death of John Crowe Ransom Author(s): Allen Tate Reviewed work(s): Source: The Sewanee Review,

Vol. 82, No. 4 (Fall, 1974), pp. 545-551 Published by: The Johns Hopkins University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/27542880 . Accessed: 09/06/2012 16:23

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

The Johns Hopkins University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Sewanee Review.

http://www.jstor.org

REFLECTIONS

ON THE

DEATH

OF JOHN CROWE RANSOM

ALLEN

JOHN

T?TE

CROWE RANSOM died on July 3, fifty-four years after the first issue of the Fugitive appeared. Donald died in 1968. Robert Penn Warren and I are left Davidson men who became poet-critics and whose lives were of the influenced by J.C.R. I would say, with Yeats, that powerfully to his lack of breath, but it will be harder I am accustomed to believe that he no longer occupies space, silent and un as he was in the last few years. Now we may ignore, knowing as we see fit, the destructive revisions which this great elegiac poet inflicted upon many of his finest poems. I wrote and gave as a speech at Kenyon College a eulogy of John on his eightieth birthday. I hope the reader will understand itwhen I say that I didn't like him while I was his student. That was more than fifty years ago. I thought him I can say this be cold, calculating, and highly competitive.

cause I, too, was calculating and competitive, and I was arro

gant enough as his student, and even later, until about 1930, to think I was a rival! But I was not, like him, cold: I was calidus juventa, running over with violent feelings, usually because my father directed at my unhappy family?unhappy now that I was in had humiliated us; and college there was

546

ON THE DEATH OF RANSOM

not enough money to see me through. My brother Ben said ( later that we were brought up with silver spoons many years in our mouths and were expected to eat the spoons.) My dislike of John was my fear of him. He had perfect self control; I could see him flush with anger, but his language was and urbane. I was just the opposite, always moderate and some of my dislike came of my exposure to his critical glance. His patience with my irregular behavior only made the more telling. What disturbed and chal his disapproval me most was my sense of the logical propriety of his lenged attitude toward his students. He never rebuked us; his subtle of attention was more powerful than reproach: withdrawal to be overtly aware of our lapses. he refused It Logic was the mode of his thought and sensibility. limited his criticism to a kind of neoclassicism, but it con tained, as "structure," his poetry; and thus the defect of the one became the virtue of the other. I have for years won dered how such an acute intelligence could seriously consider any formula for poetry, and I am still amazed that John Ran som, of all people, could come up with "structure" and "tex ture" as a critical metaphor. After the elaborate essays in Kantian philosophical aesthetics, the simple structure-texture sad as the late Yvor Winters's formula is a sad anticlimax?as

formula. Winters said, over some thirty years, that "the con

the emotion." I can't pause here for a discus cept motivates sion of these two famous prescriptive shortcuts to the mean ing of poetry; and I shall merely indicate their similarity to a somewhat less famous formula that the single word "ten

sion" conceals. It is not, of course, tension in the ordinary

sense, though certain poems may be described as "intense." the inventor of poetic "tension" had in mind was a What pun; that is, he dropped the prefixes of the pseudo-erudite tension de logical terms extension and intension, and had

ALLEN

T?TE

547

Intension is connota

Ransom's

rived from both,

tion, or Ransom's

and containing

texture; extension,

both.

denotation?or

of course, that the objects denoted are in structure?provided, an we say thatWinters's acceptable syntactical relation. May

concept is Ransom's structure, and his emotion, Ransom's

are only proximate, but these correspondences a in men of remarkably similar critical impulse no I have different ages and backgrounds. explanation of the in fact that three Americans but no Europeans astonishing the modern age tried to encapsulate poetry. In the summer of 1923 John Ransom wrote an essay en titled "Waste Lands" and published it in the Literary Review of the New York Evening Post ( later the independent Satur T. S. Eliot for the obvious reasons, day Review). He attacked such as fragmentary prosody and expository discontinuity or, as he would have later described it, lack of structure. I saw the attack as the result of his irritation with my praise of Eliot, which was that of a distant disciple, to the neglect of him, my actual master from whom I learned more than I I wrote an im could even now describe and acknowledge. texture? All they witness

pertinent?no, an insolent?reply to the essay; John answered

me; and I should have been flattered but was "hurt" instead. That is why I "disliked" him. I had already learned from for Eliot too, but I had used him, in our "Fugitive" meetings, assertion of superiority over my benighted my egotistical had discovered Eliot; who friends. Who else in Tennessee de Gourmont, G?rard de Nerval, and else had read Remy Charles Baudelaire? I was even vain about my Greek, which was quite elementary; John Ransom could have humiliated me with the professional mastery which he had acquired under Herbert Cushing Tolman (also my revered teacher) I said in "Twenty and then at Christ Church, Oxford. When Years After" that John Ransom and Donald Davidson were

548

ON

THE

DEATH

OF

RANSOM

I meant and still mean it. My "dislike" of everything to me, I repeat, was my fear of him. John, After I went to New York in 1924 he sent me his new ideas that poems and tried out some of his ideas with me?the led to the writing of his remarkable God Without Thunder. terms that book later gave me certain philosophical (This enabled me to write my contribution to I'll Take My Stand. ) John later repudiated the liturgical Christianity advocated in God Without Thunder. I still agree with the main argument of that book; that is, I don't see how Christianity can survive as a humanistic doctrine: there must be a theistic God, apo deictic and menacing as well as merciful. Almost twenty-five a review of in the New Republic, years later John wrote, Eliot's Collected Poems, in which it appears that religion is for persons who are suffering from a sense of sin, but poetry comes from, and to, those lucky people who are capable of was John's polite way of put simple delight in nature. That in his place thirty years after his rougher handling ting Eliot of that inconvenient "lion in the path." And ten years later still, he wrote a "handsome" (one of John's favorite adjec

tives in a similar context)?a very handsome analytical trib

ute to "Gerontion" for the Eliot memorial volume which I edited the year after Eliot's death. The actions of this logical

man were unpredictable.

And he was a great man?he has been near me daily since carried on his back, not his death two months ago?who an intolerable burden of conflict that only time's wallet, but and even then indirectly, came to the surface. occasionally, His reply to my attack on his "Waste Lands" seemed to dis credit me as a callow youth in revolt against his teacher; I was that, of course; but his rebuttal was, more deeply, an indirect assertion of his authoritative role at Vanderbilt Uni that authority for a recent student to question versity:

ALLEN

T?TE

549

was deeper than logic.

his position. The polemic menaced His logic justified his anger. II

the years 1922-1925 of the Fugitive, John's re During straint must have been sorely tried many times. He was the only mature poet in the group. His immature Poems About God was several years behind him, and he was writing some of the great poems which were published in Chills and Fever in 1924. John Ransom was not an innovator in the sense that both Pound and Eliot were. He was a sly, subtle innovator in ways that could not be imitated and could not found a

school. He wrote in conventional stanzas and meters, but his

sensibility owed nothing to any poet, past or present. ( Some critics have seen in him Hardy, others Donne. But this means little. Every poet resembles some other poet somewhere; if he didn't he would be an idiot. )Most of the great poems?"The Equilibrists," "Bells for John Whiteside's Daughter," "Vaunt

ing Oak," "Spectral Lovers," "Winter Remembered," "Necro

these in Chills and Fever logical," "Captain Carpenter"?all were written between 1922 and 1924. After 1924 his work in another direction: critical and lay philosophical prose. But he wrote, in the thirties, two of his finest?in my opinion his

greatest?poems: "Painted Head" and "Prelude to an Eve

ning." The latter he ruined by rewriting it so that it would have a "happy ending." Nevertheless the original version cannot be destroyed. I infer that "Painted Head" pleased him in his old age: until his literary executor finds a revised ver sion among his papers, we may believe the poem is safe. In the past ten years I have thought of John's mania (I don't know what else to call it) as the last of a truly infirmity noble mind. Yet one must see his compulsive revisions as a an extension of his reliance on quite consistent activity?as

550

ON

THE

DEATH

OF

RANSOM

standard of judgment. Consider his logic as the ultimate in 1945, in an essay "Art and the repudiation of Agrarianism Human Economy." He sent me the typescript before he pub lished it in the Kenyon Review. He dismissed Agrarianism as sense of the im sentimental and nostalgic, lacking in the mediate American reality. I urged him to suppress the essay, on the ground that when one finds a new interest, one need not an old one: one moves on. He published repudiate simply it, and lost the friendship of his old friend Donald Davidson. was only But never mind?John being logically consistent! of course, one finds the same logic back of the notorious And, at Sonnets." John had been reading essay "Shakespeare and had derived a formula for "metaphysical" poetry Donne, This the sonneteer. that raised Donne above Shakespeare a poem by Donne a co formula was strictly logical, giving herent center that a Shakespeare sonnet lacked. The editors, of the Southern Review felt that they Brooks and Warren, had to publish the essay, but only after futile efforts to get or at least to tone it down. John to suppress it It appeared in 1938, and it attracted more attention than any other essay that John had written up to that time. Among his great essays, possibly written with his logical guard down ?or it, are "Poets without perhaps the subjects bypassed Laurels" and "Wanted: An Ontological Critic." The ontologi cal critic would investigate the grades of reality that a poem embodied. What other critic, almost an exact contemporary of John's, had arrived at the same doctrine though in very different terms? What other critic had also studied philoso in some intention of teaching it or of becoming phy with the other capacity a professional philosopher? The one guess as to the answer is: T. S. Eliot. (Neither liked the other's criti cism. Eliot liked Ransom's poetry better than Ransom liked his. Eliot's opinions I got by word of mouth; Ransom's, by

ALLEN

T?TE

551

word of mouth and from published essays and reviews. ) The doctrine they shared is an ancient one that every age must rediscover. Eliot: whether a work is poetry must be decided it is great poetry, by other than by literary criteria; whether literary criteria. Ransom: the grade of being, or the ontologi cal value, of a poem must be discerned philosophically by critics of sufficient wisdom; whether the work is poetry will depend on its degree of Tightness in the structure-texture relation, neither obscuring the other. What both Eliot and Ransom arrive at in the end is that only persons of ripe ex perience both of literature and of the world can be proper critics of poetry.

Another great essay, "Poets without Laurels," I con

sider the locus classicus for insight into the relation of the modern poet to industrial-technological society. The poet is no longer a public figure; he is no longer "laureled." He is a

private person who writes poems for other poets to read. He

writes

either pure poetry obscure poetry (Stevens) All this is commonplace? The simple truth is never (T?te!). unless it is spoken by a commonplace mind. commonplace I risk the guess that Eliot's essays will be read, by that mythi cal character posterity, for their opinions; Ransom's, for their style, regardless of what they say. For John Ransom wrote the most perspicuous, the most engaging, and the most ele gant prose of all the poet-critics of our time. A few days after his death I came across (for at least the hundredth time ) an essay entitled "In Amicitia." He wrote it for my sixtieth birthday. This essay isolates me; for surely I am the only pupil who has ever had such affectionate appro bation from his master. For John Crowe Ransom was Virgil to me, his apprentice. It is proper to recall the words of

another apprentice: I salute thee, Montovano....

or

August

1974

You might also like

- To the Finland Station: A Study in the Acting and Writing of HistoryFrom EverandTo the Finland Station: A Study in the Acting and Writing of HistoryRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (123)

- Jack Lewis and His American Cousin, Nat Hawthorne: A Study of Instructive AffinitiesFrom EverandJack Lewis and His American Cousin, Nat Hawthorne: A Study of Instructive AffinitiesNo ratings yet

- Wellek Wilson PDFDocument28 pagesWellek Wilson PDFMartínNo ratings yet

- All His: Et A/. Terra Irredenta ADocument5 pagesAll His: Et A/. Terra Irredenta AjoedoedoedoeNo ratings yet

- Leavis - The Common PursuitDocument319 pagesLeavis - The Common PursuitDavid Ruaune100% (2)

- Novak - Defoe's Theory of FictionDocument20 pagesNovak - Defoe's Theory of Fictionisabel margarita jordánNo ratings yet

- Critics, Monsters, Fanatics, & Other Literary EssaysFrom EverandCritics, Monsters, Fanatics, & Other Literary EssaysRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (13)

- The Ocean, the Bird, and the Scholar: Essays on Poets and PoetryFrom EverandThe Ocean, the Bird, and the Scholar: Essays on Poets and PoetryRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (4)

- The Bit Between My Teeth: A Literary Chronicle of 1950-1965From EverandThe Bit Between My Teeth: A Literary Chronicle of 1950-1965Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (8)

- The Collected Poems of Robert Creeley, 1975–2005From EverandThe Collected Poems of Robert Creeley, 1975–2005Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (13)

- Book,: Let History JudgeDocument3 pagesBook,: Let History JudgeEluo EluoNo ratings yet

- Habib 45 Classical PoetryDocument13 pagesHabib 45 Classical Poetryhabib wattooNo ratings yet

- Edmund Wilson, Poe As A Literary CriticDocument6 pagesEdmund Wilson, Poe As A Literary CriticCaimito de GuayabalNo ratings yet

- Literary Feuds: A Century of Celebrated Quarrels--From Mark Twain to Tom WolfeFrom EverandLiterary Feuds: A Century of Celebrated Quarrels--From Mark Twain to Tom WolfeRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (18)

- Ted Hughes InterviewDocument15 pagesTed Hughes InterviewAndrew RiccaNo ratings yet

- A Brief Guide To Metaphysical PoetsDocument12 pagesA Brief Guide To Metaphysical PoetsVib2009No ratings yet

- Bloom The EpicDocument281 pagesBloom The Epicreferee19803292% (13)

- Writing A Critical BiographyDocument24 pagesWriting A Critical BiographyantoniomarcospereiraNo ratings yet

- The Collected Essays Volume One: Occasional Prose, The Writing on the Wall, and Ideas and the NovelFrom EverandThe Collected Essays Volume One: Occasional Prose, The Writing on the Wall, and Ideas and the NovelNo ratings yet

- Thomas de Quincey by H.S. DaviesDocument19 pagesThomas de Quincey by H.S. DaviesCarlos RoderoNo ratings yet

- Paris Review - The Art of Fiction No. 207, Jonathan FranzenDocument23 pagesParis Review - The Art of Fiction No. 207, Jonathan FranzenAlysson Oliveira50% (2)

- Hypocrisy and the Philosophical Intentions of Rousseau: The Jean-Jacques ProblemFrom EverandHypocrisy and the Philosophical Intentions of Rousseau: The Jean-Jacques ProblemNo ratings yet

- The City in Literature: An Intellectual and Cultural HistoryFrom EverandThe City in Literature: An Intellectual and Cultural HistoryRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- Dostoevsky and VonnegutDocument13 pagesDostoevsky and VonnegutMattNo ratings yet

- Steiner, George. Grammars of CreationDocument13 pagesSteiner, George. Grammars of Creationshark123KNo ratings yet

- Literary Criticism As An Art Form Is Only A Few Decades Old in The PhilippinesDocument7 pagesLiterary Criticism As An Art Form Is Only A Few Decades Old in The PhilippinesBenedick ReyesNo ratings yet

- Renaissance Self-Fashioning: From More to ShakespeareFrom EverandRenaissance Self-Fashioning: From More to ShakespeareRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (35)

- The Waste Land and Other Poems 100th Anniversary International EditionFrom EverandThe Waste Land and Other Poems 100th Anniversary International EditionNo ratings yet

- Book Reviews: Commitment DilemmaDocument3 pagesBook Reviews: Commitment DilemmaelektrenaiNo ratings yet

- Ts Eliot ThesisDocument5 pagesTs Eliot Thesisafktgmqaouoixx100% (2)

- "Oh, Do Not Ask, What Is It?'" in Eliot's The Lovesong of J. Alfred Prufrock' and Gerontion'Document6 pages"Oh, Do Not Ask, What Is It?'" in Eliot's The Lovesong of J. Alfred Prufrock' and Gerontion'Ipshita NathNo ratings yet

- Giving the Devil His Due: Demonic Authority in the Fiction of Flannery O’Connor and Fyodor DostoevskyFrom EverandGiving the Devil His Due: Demonic Authority in the Fiction of Flannery O’Connor and Fyodor DostoevskyNo ratings yet

- Gregor FRLeavis 1985Document14 pagesGregor FRLeavis 1985Yoon Eun JiNo ratings yet

- Leonard Cohen, Untold Stories: That's How the Light Gets In, Volume 3From EverandLeonard Cohen, Untold Stories: That's How the Light Gets In, Volume 3No ratings yet

- The Soul and Barbed Wire: An Introduction to SolzhenitsynFrom EverandThe Soul and Barbed Wire: An Introduction to SolzhenitsynRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- A Change in Criticism With Special Regar PDFDocument10 pagesA Change in Criticism With Special Regar PDFMöĤämmĔd äĹ-ŚäÁdïNo ratings yet

- Nobody's Business: Twenty-First Century Avant-Garde PoeticsFrom EverandNobody's Business: Twenty-First Century Avant-Garde PoeticsRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Angry Young Men 1965Document10 pagesAngry Young Men 1965Machete9812No ratings yet

- Research Paper John DonneDocument4 pagesResearch Paper John Donnefvgczbcy100% (1)

- Poetry ProjectDocument31 pagesPoetry ProjectAisha SiddiqaNo ratings yet

- A World More Attractive Essays On Modern Literature and Politics - Irving HoweDocument328 pagesA World More Attractive Essays On Modern Literature and Politics - Irving HoweRJJR0989No ratings yet

- Please of Hating AnalysisDocument7 pagesPlease of Hating AnalysisNicholas TumbasNo ratings yet

- Modernismo Tema 3-6Document17 pagesModernismo Tema 3-6Nerea BLNo ratings yet

- Modern Heroism: Essays on D. H. Lawrence, William Empson, and J. R. R. TolkienFrom EverandModern Heroism: Essays on D. H. Lawrence, William Empson, and J. R. R. TolkienNo ratings yet

- T.S. Eliot As A CriticDocument3 pagesT.S. Eliot As A CriticSaleem Raza80% (5)

- PrefaceDocument9 pagesPrefaceRashmiNo ratings yet

- NTTA List of Invoices Sent To Amber YoungDocument8 pagesNTTA List of Invoices Sent To Amber Youngmlindenberger25No ratings yet

- Dart Petition Regarding Debt LimitsDocument25 pagesDart Petition Regarding Debt Limitsmlindenberger25100% (1)

- Cover Letter From Locke Lord To DMNDocument2 pagesCover Letter From Locke Lord To DMNmlindenberger25No ratings yet

- NTTA List of Large Delinquent Toll AccountsDocument710 pagesNTTA List of Large Delinquent Toll Accountsmlindenberger250% (2)

- Art of MemoirDocument10 pagesArt of Memoirmlindenberger25No ratings yet

- d10 Sandra Darby FinalDocument3 pagesd10 Sandra Darby FinalFirstCitizen1773No ratings yet

- Historical Roots of The "Whitening" of BrazilDocument23 pagesHistorical Roots of The "Whitening" of BrazilFernandoMascarenhasNo ratings yet

- Supply Chain Management 101Document36 pagesSupply Chain Management 101Trần Viết ThanhNo ratings yet

- (2016) A Review of The Evaluation, Control and Application Technologies For Drillstring S&V in O&G WellDocument35 pages(2016) A Review of The Evaluation, Control and Application Technologies For Drillstring S&V in O&G WellRoger GuevaraNo ratings yet

- LampiranDocument26 pagesLampiranSekar BeningNo ratings yet

- Indian Pharmaceutical IndustryDocument25 pagesIndian Pharmaceutical IndustryVijaya enterprisesNo ratings yet

- Hospital Furniture: Project Profile-UpdatedDocument7 pagesHospital Furniture: Project Profile-UpdatedGaurav GuptaNo ratings yet

- L Rexx PDFDocument9 pagesL Rexx PDFborisg3No ratings yet

- Max9924 Max9927Document23 pagesMax9924 Max9927someone elseNo ratings yet

- MT Im For 2002 3 PGC This Is A Lecture About Politics Governance and Citizenship This Will HelpDocument62 pagesMT Im For 2002 3 PGC This Is A Lecture About Politics Governance and Citizenship This Will HelpGen UriNo ratings yet

- Citing Correctly and Avoiding Plagiarism: MLA Format, 7th EditionDocument4 pagesCiting Correctly and Avoiding Plagiarism: MLA Format, 7th EditionDanish muinNo ratings yet

- OIl Rig Safety ChecklistDocument10 pagesOIl Rig Safety ChecklistTom TaoNo ratings yet

- Harish Raval Rajkot.: Civil ConstructionDocument4 pagesHarish Raval Rajkot.: Civil ConstructionNilay GandhiNo ratings yet

- Konsep Negara Hukum Dalam Perspektif Hukum IslamDocument11 pagesKonsep Negara Hukum Dalam Perspektif Hukum IslamSiti MasitohNo ratings yet

- Busbusilak - ResearchPlan 3Document4 pagesBusbusilak - ResearchPlan 3zkcsswddh6No ratings yet

- Comsol - Guidelines For Modeling Rotating Machines in 3DDocument30 pagesComsol - Guidelines For Modeling Rotating Machines in 3DtiberiupazaraNo ratings yet

- Mass and Heat Balance of Steelmaking in Bof As Compared To Eaf ProcessesDocument15 pagesMass and Heat Balance of Steelmaking in Bof As Compared To Eaf ProcessesAgil Setyawan100% (1)

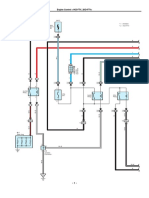

- Diagrama Hilux 1KD-2KD PDFDocument11 pagesDiagrama Hilux 1KD-2KD PDFJeni100% (1)

- Cognitive-Behavioral Interventions For PTSDDocument20 pagesCognitive-Behavioral Interventions For PTSDBusyMindsNo ratings yet

- 5 Teacher Induction Program - Module 5Document27 pages5 Teacher Induction Program - Module 5LAZABELLE BAGALLON0% (1)

- Video Course NotesDocument18 pagesVideo Course NotesSiyeon YeungNo ratings yet

- AURTTA104 - Assessment 2 Practical Demonstration Tasks - V3Document16 pagesAURTTA104 - Assessment 2 Practical Demonstration Tasks - V3muhammaduzairNo ratings yet

- Acdc - DC Motor - Lecture Notes 5Document30 pagesAcdc - DC Motor - Lecture Notes 5Cllyan ReyesNo ratings yet

- Pin Joint en PDFDocument1 pagePin Joint en PDFCicNo ratings yet

- Tournament Rules and MechanicsDocument2 pagesTournament Rules and MechanicsMarkAllenPascualNo ratings yet

- Project ProposalDocument2 pagesProject Proposalqueen malik80% (5)

- Arte PoveraDocument13 pagesArte PoveraSohini MaitiNo ratings yet

- Asugal Albi 4540Document2 pagesAsugal Albi 4540dyetex100% (1)

- Regression Week 2: Multiple Linear Regression Assignment 1: If You Are Using Graphlab CreateDocument1 pageRegression Week 2: Multiple Linear Regression Assignment 1: If You Are Using Graphlab CreateSamNo ratings yet

- Master Thesis On Smart GridDocument6 pagesMaster Thesis On Smart Gridsandraandersondesmoines100% (2)