Professional Documents

Culture Documents

633-Revised1 - My Counselling Theoryassignment

Uploaded by

api-163017967Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

633-Revised1 - My Counselling Theoryassignment

Uploaded by

api-163017967Copyright:

Available Formats

RUNNING HEAD: My Counselling Theory

My Personal Theory of Counselling Pasquale Veleno Human Development: CAAP 633 Professor: J. Willment April 13, 2012

RUNNING HEAD: My Counselling Theory

Shortly after obtaining my undergraduate degree in psychology, I was hired to work in a direct care capacity with autistic and developmentally delayed children and young adults at a treatment centre close to my home. The program for which I was hired had a mandate to service highly behavioural individuals, many of whom were dually diagnosed, and were placed in a residential setting due to the difficulties associated with their ongoing care. As an inexperienced recent graduate entering the workforce for the first time, this hiring presented an opportunity for me to gain a deeper understanding of many of the theoretical concepts I learned about in my undergraduate studies. Moreover, my employment at this facility exposed me to the principles of Applied Behaviour Analysis (ABA) for the first time, and taught me how to systematically assess behaviour, gather data, and analyze program effectiveness. It also gave me a new perspective and deeper understanding of concepts associated with learning theory. These principles were utilized in an applied setting to effectively teach functional life skills, academic and social skills. As I gained experience, I became increasingly familiar and comfortable with the concepts of behavioural theory, naturally, and I found myself exponentially drawn to the behavioural approach. Within a few years, I began working as a behaviour therapist whereupon I was introduced to elements of cognitive-behavioural therapy, and taught to apply these concepts with the various clinical populations I serviced, including children and adults with autism, developmental disabilities, mental health issues, and acquired brain injury (ABI). I found value in using cognitive-behavioural techniques to effectively alter faulty thinking patterns and improve overall functioning for clinical problems including depression, anxiety, anger management, phobias and fears, and self-esteem. I have continued to work as a behaviour therapist for children and adults,

RUNNING HEAD: My Counselling Theory

using behavioural and cognitive-behavioural strategies, for approximately thirteen years to this point. My life experiences, both personal and professional, have shaped who I am as a counsellor. My familiarity and relative success with the behavioural and cognitive-behavioural philosophies, respectively, serves to bias me toward these approaches, and this has strongly influenced the formulation of my personal theory of counselling. The remainder of this paper will provide an overview of my current counselling theory and the concepts upon which it is based. Further to this, I will incorporate material from this course to identify which developmental issues and theories that both support and challenge my theoretical orientation. Strengths and limitations of my personal theory of counselling will be explored, and finally, the paper will be concluded with personal self-reflection, whereby future directions and implications for practice will be reviewed. My Personal Theory of Counselling An integrated behavioural-cognitive behavioural approach represents an amalgamation of two empirically based, scientific theories that form the basis of my personal theory of counselling. Traditional behavioural and cognitive-behavioural approaches are based on the assumption that human beings are products of their environment, while simultaneously being capable of manipulating and influencing environmental outcomes. As behavioural theory has evolved, an increased emphasis has been placed on cognitive processes, including how thoughts influence emotions and behaviours, thereby making this approach increasingly appealing to me. Credence is given to the roles of both nature and nurture, respectively, as it pertains to shaping personal outcomes, thereby representing a broader, more applicable philosophical approach.

RUNNING HEAD: My Counselling Theory

Behaviour therapy, based on principles of learning theory, postulates that problematic behaviours are a result of learned responses that are subject to laws, which govern all behaviour (Coleman, 1992). As such, behaviours are not considered intrinsically deviant per se, but

rather they are deemed problematic insofar as they differ significantly from societal norms (Coleman, 1992). Russ (1974) identified five major assumptions common to behavioural theory: behaviour is a basic characteristic of living organisms; behaviour is modifiable through learning; while other contributing factors exist, most human behaviour is learned behaviour; change in behaviour is a function of change in environment (behaviour adapts to environmental conditions); and, a lawful relationship exists between behaviour and events in the environment. Since behavioural theory presupposes that most human behaviour is learned, it therefore also suggests that maladaptive behaviour can also be extinguished and replaced with new, more adaptive behaviour. Secondly, the environment plays a significant role in eliciting and maintaining behaviours. Finally, behaviourism stresses the study of observable behaviour (Coleman, 1992). Traditional behavior therapy focuses on addressing current environmental variables maintaining problem behaviour, with little importance given to the need to understand its origins (Wilson, 2008). Treatment protocols are individually tailored to meet client needs, subsequent to the analysis of the function of behaviour, using a scientifically based approach amenable to empirical evaluation. Moreover, behaviour therapy seeks to increase individual freedoms by building skills that would otherwise serve to improve an individuals ability to function within their environment (Kazdin, 1978, 2001). Skill acquisition and psychological improvements are assessed by measuring improvements in observable behaviour. In this manner, the behavioural approach places great emphasis on empiricism, science and replication.

RUNNING HEAD: My Counselling Theory Conversely, cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) incorporates both cognitive and

behavioural principles to develop methods that address thoughts, feelings and behaviors as well (Dattilio, 2000). Although modern behaviour therapeutic principles include cognitive aspects an integral piece of the therapeutic puzzle, CBT goes further to incorporate the role of cognitions and their influences on affect and behaviour, in the therapeutic process. Emotional and

behavioral disturbances therefore result from faulty thinking patterns, or internal dialogue, that contributes to behavioral response patterns (Corey, 2009). Disorders arise and are maintained by current thinking patterns, which must be challenged and eventually modified in order to prompt positive change. CBT, in particular, also acknowledges the role that genetic predisposition plays in the development of emotional disturbance. On a personal level, I believe that the complex interaction between personal and environmental factors serves to shape the human experience. Internal factors such as perceptions, thoughts, motivations, for example, cannot be discounted. They play a significant role in the development of behavioural outcomes. Social-cognitive theory, for example, recognizes the interconnection between stimulus, reinforcement and cognition. The focus on both internal mediating factors and external factors that contribute to individual functioning is appealing to me because it recognizes that people are complex, intelligent, and driven by internal and external forces. Human beings are unique and distinct. Social-cognitive theory suggests that behaviour is largely affected by how environmental events are perceived and interpreted. In this manner, it is believed that there is an element of mutual influence between the environment and the individual; whereby an individuals actions affect environmental conditions, and the environmental conditions have a reciprocal effect on behaviour (Wilson, 2008). People gravitate toward things they like, and avoid or move away from things they dislike or find punishing.

RUNNING HEAD: My Counselling Theory

Furthermore, social-cognitive theory recognizes the critical role of vicarious learning, cognitions, including individual interpretation of events and faulty perceptions; self-regulation and expectations, have on treatment outcomes. While the social-cognitive theory of learning has coincided with my beliefs about the influence of nature vs. nurture on human development to this point, my experience within this course has somewhat altered my thinking in this regard. Multidimensional or systems theories assume that in all behavioural domains, from cognition to personality, there are layers, or levels, of interacting causes for change: physical/molecular, biological, psychological, social, and cultural (Broderick & Blewitt, p. 14). In this manner, relationships between all possible variables are bidirectional, and, in my opinion, more effectively reflect the complex nature of the dynamics between contributing factors to human development. Bronfenbrenners bioecological theory of development provides an example of a systemsbased theory that appeals to me. This model places emphasis on an individuals reciprocal interactions with the environment (Broderick & Blewitt, 2010). According to Bronfenbrenners theory, all human development results from a function of proximal processes, which entail reciprocal interactions between an individual and the persons, objects or symbols within the immediate environment; or distal processes, which include features that are outside of the immediate environment, such as genetics, for example (Broderick & Blewitt, 2010). characterization of the many levels within the environment that serve to shape human development include the microsystem, including the family and those within the immediate environment; the mesosystem, which is meant to describe the interaction between two separate microsystems; the exosystem, encompassing an environment that the child does not directly interact with but has influence, such as ones socioeconomic status; and, the macrosystem, which His

RUNNING HEAD: My Counselling Theory

incorporates customs and cultural influences. In this way, Bronfenbrenners multidimensional model highlights the notion that human beings, therefore, are both products and producers of the environment. It is my belief that all human beings, regardless of cognitive functioning, have the capacity to learn, and as such, possess the innate ability for personal growth. In my own experience, I have used behaviour analytic techniques to effectively teach even profoundly delayed individuals to acquire new skills and improve overall quality of life. Applied behaviour analysis (ABA) is defined as the science in which procedures derived from the principles of behaviour are systematically applied to improve socially significant behaviour to a meaningful degree and to demonstrate empirically the procedures employed were responsible for the improvement (Baer, Wolf, & Risley, 1968). Applied behaviour analysts believe that behaviour is largely a function of environmental contingencies that serve to either increase or decrease the likelihood for behavioural recurrence. This approach relies on operant conditioning principles to guide treatment. The focus of intervention therefore is based on altering relationships between overt behaviours and consequent events. This is accomplished via the use of reinforcement, punishment, extinction, stimulus control, and other procedures derived from experimental research (Corey, 2009). Applied behaviour analysis places little importance on cognitive processes since these events are considered private, unobservable, and not appropriate for scientific analysis (Wilson, 2008). I believe that individual thoughts and perceptions are significant factors that contribute to overall functioning. Therefore, faulty thinking patterns, including problems with interpretation, perception, or analysis of life events, can lead to the occurrence of behavioural, emotional and psychological issues. By remedying flawed patterns of thinking or teaching adaptive skills, the

RUNNING HEAD: My Counselling Theory

counsellor arms the client with the tools for success. Cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT), places greater emphasis on the role of thinking in the presentation of and treatment of behavioural and emotional problems (Corey, 2009). In a broad sense, as behaviour therapy has evolved, its practices have been based on social-cognitive theory and have encompassed many of the cognitive principles and procedures associated therein (Wilson, 2008). The techniques associated with CBT focus on cognitive processes that involve private events as crucial variables inherent in the process of behaviour change. Treatment is an individualized process largely dependent upon the needs of the client. I believe that the relationship between client and counsellor must be based on trust, collaboration, and acceptance. In order to promote therapeutic success, the client must share responsibility in the process of goal setting and treatment planning. While a therapeutic relationship is advantageous to treatment success, it is not necessary (Ellis, 2008). Rather, treatment success is more a function of the therapeutic techniques utilized. The counsellor takes an active approach and uses teaching techniques to help the client learn new skills for the purposes of achieving therapeutic goals (Corey, 2009). Treatment decisions are bound by adherence to the highest ethical and professional standards. Ethical standards exist as a means of protecting the individual rights and freedoms of each person within society. Ethical standards are concerned with greater social justice and responsibility. They are aspirational in nature, and as such, seek to attain the higher good for the both the individual and society, respectively. As such, counsellors have an ethical responsibility to society as a whole, and particularly to the individual members within society, regardless of culture, race, religion, socioeconomic status, and/or other interpersonal characteristics. Of course, all members within society are not equal, and therefore, certain individuals are

RUNNING HEAD: My Counselling Theory

considered vulnerable by way of barriers associated with physical, developmental, mental health or other challenges. Social justice is about ensuring that all people have access to resources and are treated fairly regardless of their status within society (p. 123, Truscott and Crook). Based on a deontological approach, counsellors have special responsibilities to vulnerable persons, since by the very definition of the word "vulnerable" they are predisposed to greater potential for abuse, hardship, and/or inequality. In order to provide equal opportunities therefore, counsellors must seek to assist vulnerable people to overcome and/or compensate for their vulnerabilities, which help ensure that everyone has similar opportunities for success, quality of life, etc., and does not discriminate on the basis of physical/developmental/other limitations. According to the CPA Code of Ethics, psychologists recognize that as individual, family, group, or community vulnerabilities increase, or as the power of persons to control their environment or their lives decreases, psychologists have an increasing responsibility to seek ethical advice and to establish safeguards to protect the rights of the persons involved (p.45). All should be treated fairly,fairly; however this doesn't necessarily mean that people should be treated equally. Truscott and Crook argue that the ethical requirement of social justice means that "equals must be treated as equals, and unequals must be treated as unequals (p.126)". It could therefore be argued that all people should have equal opportunities to have their needs met, though in order to do so, vulnerable populations in particular, would require increased access to extra resources, increased levels of support, adaptations and modifications, etc. to more closely approach a level of fairness and/or equality. By doing so, society is inherently respecting the rights of vulnerable people, and preserving their dignity.

RUNNING HEAD: My Counselling Theory Theoretical and Developmental Issues

10

Human development can be viewed from a variety of competing perspectives. From the onset of this course, we have been asked to consider major issues in development from four major, divergent perspectives, while arguing the strengths and weaknesses of each, respectively. In considering the various developmental theories examined within this course, it has become increasingly apparent to me that development is a complex process that cannot be easily and readily summarized using any singular extreme perspective or theoretical approach. Human development can best be described as a synthesis ofextremes (p.18, Broderick & Blewitt, 2010). The contemporary cognitive-behavioural orientation that I align with incorporates a relatively balanced outlook regarding the developmental perspectives across the lifespan, thereby acknowledging influential elements from competing arguments. While traditional behaviour therapy places strong emphasis on environmental contributions to behaviour, contemporary behaviourism and cognitive-behaviour therapy stresses the role of internal mechanisms including thought processes and learning on emotional and behavioural disturbances (Corey, 2009). The acknowledgement of the role of competing perspectives is highlighted in the following section by considering developmental issues using the four major theoretical arguments used in this class. Nature and nurture. The nature vs. nurture debate is centered on the relative contributions of

genetic and environmental factors to human development. At the core of the argument lies the following question: are human beings by-products of their genetic makeup or are they byproducts of their environment? Developmental researchers have come to acknowledge the bilateral role that both factors play on behavioural outcomes (Broderick & Blewitt, 2010). In

RUNNING HEAD: My Counselling Theory fact, genetic variables and environmental variables are largely considered to interact interdependently, mutually serving to differentially influence developmental outcomes (Broderick & Blewitt, 2010).

11

In a class paper exploring depression from these competing perspectives that I coauthored, strong evidence for the argument that depression is a biologically-based disorder, as evidenced by a study by Caspi et al. (2003), was found indicating that individuals with dysfunctional 5-HTT alleles are more vulnerable to depression than those carrying the functional 5-HTT allele (Mackenzie, Restoule, & Veleno, 2012). Further supporting this proposition, Caspi et al. (2003) found that carriers of an s 5-HTTLPR allele accounted for almost one-quarter (23%) of the 133 subjects diagnosed with depression in the study (Mackenzie, Restoule, & Veleno, 2012). Conversely, a study by Pahkala (1990), which examined 1529 Finnish subjects aged 60 or older to assess the effects of social and environmental factors in depression in old age found a positive correlation between depression and individuals who retired due to sickness rather than age, individuals who had few hobbies, reduced number of meaningful relationships, and longstanding social stress factors (p.9, Mackenzie, Restoule, & Veleno, 2012). Furthermore, subjects were more likely to be depressed when psycho-social factors such as relationship status, amount of time spent alone, distant/poor relationships with significant others, etc., were problematic (Mackenzie, Restoule, & Veleno, 2012). Results of this study strongly suggest

that social/interpersonal and environmental stressors have a meaningful impact with respect to the onset of depression in older adults. Finally, using the biopsychosocial model, we, the authors, recognized the interaction between the multitude of factors, including age, gender, life experiences and transitions, social

RUNNING HEAD: My Counselling Theory

12

interactions, sunlight, neurochemical changes in the brain, changes in cognition and emotion, genetic predisposition, changes in family support, substance abuse, self-concept, grieving/loss, etc., that simultaneously contribute to the onset of depression. According to this model, the (biological) variables contributing to vulnerability for depression and the (environmental) variables that serve as stressors reciprocally cause and are caused by one another, according to O Connor, 2003 (as cited in Mackenzie, Restoule, & Veleno, 2012). We, the authors, therefore argued that the biopsychosocial model promotes a synthesis of knowledge from multiple viewpoints that facilitates an understanding that depression is a continuous, self-reinforcing system of interactions, influenced simultaneously by nature and nurture. Critical periods and plasticity. The question of whether particular skill acquisition is dependent upon certain developmental time frames, called critical periods, or whether skill acquisition can occur throughout the life span, given the right circumstances, forms the basis of the critical periods and plasticity argument (Broderick & Blewitt, 2010). I believe, as do most contemporary behaviorists, including those identifying with the cognitive-behavioural philosophy, that human behaviour is a function of learning. It is therefore given that, in order to affect therapeutic change, one must have the capacity to learn, regardless of the stage of development. This notion is biased heavily in flavour of plasticity perspective within this debate. A study by Pinker (1994), as cited within Broderick & Blewitt (2010), notes that language can be learned across the lifespan, however it is never learned as well or as easily as it would have been during the period from ranging to age 5 years, thereby suggesting that a critical period exists for language acquisition.

RUNNING HEAD: My Counselling Theory

13

In a Blackboard discussion during week #2 of this class, students were asked to consider one of Piagets stages of early cognitive development using one of the four major perspectives issued in human development. Veleno (2012) chose to answer the question from the critical periods and plasticity perspective: Piaget describes the Preoperational Stage as a period highlighted by a childs preschool years, i.e. age 2 to 5 years of age. During this time, significant language acquisition takes place, and is almost complete by the end of the preoperational stage. Children largely acquire the phonology of language, encompassing the subset of sounds consistent with language: the semantic system of language, which is related to word parts and their meanings; the syntactic system (grammar); and finally, the pragmatics of language. During the preoperational stage, a child typically experiences a sudden increase in the acquisition of words within a relatively short period of time between the ages of 18 and 24 months. Subsequent to the end of the preoperational stage, the rate of language acquisition and development slows drastically. This suggests that, for language to take place within this specific time frame, a critical period of development is inherent. This does not adequately explain how individuals acquire a second (or third) language later in life, nor does it account frofor the loss of language subsequent to a traumatic event such as an acquired brain injury (ABI), and the resultant re-acquisition of language, albeit at a slower rate. The possibility of language acquisition in later years strongly reinforces the notion of plasticity, while the re-acquisition of a primary language subsequent to an ABI further highlights the power of the brain to adapt, to create new neural pathways, and to learn beyond what Piaget deemed as the critical period. Hensch (2004) suggests that

RUNNING HEAD: My Counselling Theory

14

sensitivity to some new learning opportunities does appear to vary across the life span as a function of changes in the nervous system" (Broderick & Blewitt, 2010), however several personal and environmental variables appear to have an impact upon learning. With that said, studies appear to suggest that the rate of language acquisition is most efficient during the preoperational stage. This suggests that the case for a critical period of language acquisition can be made, however the value and impact of plasticity in this regard cannot be discounted. (Q2) By acknowledging the importance of critical periods to the development of specific skill sets while reinforcing the idea of plasticity, a reasonable balance is struck between the two competing perspectives. Continuity and discontinuity. The issue of continuity and discontinuity can best be described by considering whether developmental change occurs gradually over time, or whether it occurs in rapid transformations over specific stages (Broderick & Blewitt, 2010). Stage theorists, such as Erikson and Piaget, argue that development occurs through a sequence of fixed-order, qualitative, age-graded changes characterized by the achievement of milestones that werent present or fully acquired in a previous stage (Broderick & Blewitt, 2010). In this regard, they emphasize discontinuity, as it pertains to human development. Incremental theorists, such as Bandura, Skinner, and Watson, however favor continuity, preferring the notion that change is gradual and specific to particular behaviours or mental activities (Broderick & Blewitt, 2010). Social learning theorists prefer the continuous approach to learning and explain behavioural change as a function of environmental events that, when paired with certain behaviours, serve to either increase the recurrence of those behaviours via classical or operant conditioning (Broderick & Blewitt, 2010).

RUNNING HEAD: My Counselling Theory

15

Prior to taking this course, I would have easily identified with incremental theorists in believing human development to be gradual, continuous and heavily influenced by environmental conditions that influence learning. However, after considering a multidimensional approach such as Bronfenbrenners bioecological model, I have come to give greater consideration to the effects of multiple influences both proximal and distal on human development because it offers a more comprehensive and integrative approach than any other theoretical approach, and as such, reflects the complex dynamics that influence development. Multidimensional perspectives propose that continuity persists if environmental mechanisms continue to sustain it (Broderick & Blewitt, 2010). According to Bronfenbrenners model, the

richness of the environment in the microsystem plays a crucial role in the development of the child. The mother-child, father-child, and father-mother dyads form the basis of the early microsystem, and are considered most influential at that stage (Paquette & Ryan, 2001). These two person systems are bi-directional in nature (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). Much of a childs behavior is learned in the microsystem, though as the child ages, the other, more distant, systems have increasing influence (Paquette & Ryan, 2001). By using this model, influential factors such as individual abilities, biological status, stage of development, cultural and familial influences are given consideration that would otherwise be ignored or de-emphasized using a social learning approach. According to bioecological theory, if the relationships in the immediate microsystem break down, the child will not have the tools to explore other parts of his environment. Activity and passivity. Is human development intrinsically and active or passive process? The mechanistic view suggests that development can be reduced to a chainlike sequence of events (Broderick & Blewitt, 2010). This approach is consistent with early behavioural theory.

RUNNING HEAD: My Counselling Theory

16

Organismic theories of development, conversely, suggest that human beings are active initiators of their own environment. I believe in a bi-directionality of influence, as it pertains to the activity and passivity debate. Humans are both products and producers of the environment. By taking this stance, I acknowledge the that human beings are shaped by our personal experiences through principles of operant conditioning; while simultaneously having the capacity to initiate change and influence outcomes. In this sense, I believe in constructivism. Using a selforganizing approach, multidimensional and constructivist theories propose that individuals purposefully incorporate and promote processes, activities, people and strategies that enhance and enrich their lives (Broderick & Blewitt, 2010). Where this is not possible, people have the power to change their own perceptions by constructing a more positive and healthier outlook on the factors that cannot be controlled (Broderick & Blewitt, 2010). In a Blackboard posting during week #5 of this class, Veleno (2012) posted the following: social development is shaped in large part by an individuals ability to engage in rulebased social contact. For example, by the preadolescent stage, children's social needs are met by the establishment of close relationships with a peer or peers, and these relationships encourage active perspective taking, and reciprocal social behaviours that illustrate a child's understanding of the importance of others. A child is an active participant in establishing these interpersonal connections with like-minded or interesting peers, and demonstrating the ability to engage in a mutually beneficial relationship via collaboration, active problem solving, compromise, etc. The effective application of social skills results in making and keeping friends. In this sense, it too is a very active approach.

RUNNING HEAD: My Counselling Theory Implications for Practice

17

My primary role as counsellor will continue to require that I work with children and adults with a range of developmental disabilities, acquired brain injuries, and/or mental health issues who present with challenging behaviours. The primary goal of therapy is to promote skill acquisition by addressing faulty thinking patterns and problematic behaviour. This will require that I arrange contingencies that serve to reinforce adaptive thoughts and appropriate replacement behaviours, i.e. functional behaviours that are more adaptive and socially acceptable. While I acknowledge the role of past experiences on current psychological problems and behaviour, the focus of therapeutic intervention is on the present since current problems are likely the result of reinforcement for present ways of thinking (Corey, 2009). CBT looks to alter defective patterns of internal dialogue, including faulty assumptions and misconceptions, so as to replace them with adaptive responses (Corey, 2009). As such, theories of counselling based on cognitive-behavioural philosophies aim to teach the client to use techniques that will help prevent the occurrence of future psychological distress as a result of the acquired abilities to problem-solve and manage problems more effectively. Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy (REBT), for example, utilizes a model, which considers the client interaction between feelings, thoughts, events and behaviors (Corey, 2009). An activating event (A) can consist of the behaviour or attitude of an individual can prompt the occurrence of an emotional and behavioral consequence (C), however this is mediated by the individuals belief (B) about the activating event. Disputing (D) refers to the process of challenging the individuals irrational beliefs by detecting the irrational beliefs, debating the irrational beliefs by questioning and discriminating irrational beliefs from rational beliefs. This process leads to cognitive restructuring, which essentially involves the replacement of faulty cognitions with more adaptable beliefs. This

RUNNING HEAD: My Counselling Theory

18

ultimately serves to help the client attain an effective philosophy or belief system (E), resulting in new feelings (F). Depending upon the nature or severity of intellectual deficits, hat my future clients will have, it may or may not be appropriate to utilize an approach that focuses on cognitive processes. In cases where clients are significantly delayed, it is more reasonable to adopt an approach that focuses on altering environmental contingencies as a means of reinforcing desired behaviour, and withholding reinforcement for undesired behaviour. In this sense, my theoretical approach allows for great flexibility. My theory of counselling is widely applicable across a number of clinical populations and problems. Some problems to which a behavioural or cognitivebehavioural approach is well suited include phobic disorders, depression, trauma, childrens behavioural disorders, anxiety, relationship problems, and stress management (Corey, 2009). Furthermore, there is a wide range of therapeutic techniques available to treat the identified problem in an individualized manner. Quality intervention is preceded by the clear identification and definition of the problem and an objective, empirically based system of evaluation. Upah and Tilly (2004) define a problem as the difference between what is expected and the actual student behaviour or performance (p. 484). The step is a particularly important one insofar as it helps to establish and clarify the intent to resolve the difference between current performance and desired outcomes. In order to evaluate program effectiveness, it is essential that the clients current level of functioning be established prior to the introduction of treatment. By doing so, a baseline is established which facilitates the evaluation of client progress by allowing the comparison between pre-treatment and post-treatment conditions. Further to this, it is important to establish

RUNNING HEAD: My Counselling Theory

19

a manner to systematically measure the behaviour which takes into account how the data will be collected, under what conditions and settings the data will be collected, who will collect the data, and how often the data will be collected (Upah & Tilly, 2003). Ideally, baseline data is collected over a period of several days or weeks, and over the course of several sessions and/or settings so as to provide an accurate reflection of contingencies maintaining the behaviour (Martin & Pear, 2003), and treatment decisions are based on empirically validated results. Given its focus on empiricism and evidence-based practices, behaviour therapy has been subjected to copious amounts of scientific research. It has been studies more intensively than any other form of psychological treatment (Wilson, 2008). Evidence-based therapies are a hallmark of behaviour therapies (Corey, 2009). Behaviour therapists utilize interventions that have been subjected to rigorous evaluation (Wilson, 2008), and continue to collect treatment performance data on an ongoing basis, since this is an expectation of practice. According to Corey (2009), compared with other approaches, behavioural techniques have been found to be as effective or more effective in changing target behaviours related to anxiety disorders, depression, OCD, panic disorder and phobias (Kazdin, 2001; Speigler & Guevremont, 2003). The strong focus on empiricism and evidence-based practice partially upholds ethical and professional standards of practice, and is consistent with the Canadian Code of Ethics for Psychologists. The four guiding principles of the CPA Code of Ethics include: Principle I: Respect for the Dignity of Persons, Principle II: Responsible Caring, Principle III: Integrity in Relationships, and Principle IV: Responsibility to Society. By adhering to these principles, the psychologist engages in a higher duty of care to society and to the individual members of society. In particular, the psychologist has a higher duty of care for vulnerable populations. This endeavor plays a role in social justice and responsibility. Of particular relevance in this case are Principle(s) I: Respect

RUNNING HEAD: My Counselling Theory

20

for the Dignity of Persons, which requires that each person should be treated primarily as a person or an end in him/herself, not as an object or a means to an end (p.43, Sinclair & Pettifor, 2001)and psychologists acknowledge that all persons have a right to have their innate worth as human beings appreciated (p.43, Sinclair & Pettifor, 2001); and, Principle II: Responsible Caring, which requires counsellors to engage in activities that will benefit members of society or, at least, do no harm (p.57, Sinclair & Pettifor, 2001 )2001). Limitations of this amalgamated approach relate to the limited importance placed on emotions and personal insight, while de-emphasizing the historical determinants of behaviour (Corey, 2009). Critics of this approach may claim that because insight is not a primary focus of treatment, and because of this the root of the problem may be left unresolved. As such it could be argued that clients may be likely to replace newly resolved symptoms with novel problematic symptoms. Further to this, my theoretical orientation may fail to give enough consideration to possible distal or proximal variables that an integrated, multidimensional approach would include. As a result, this approach, while acknowledging internal and external factors, may not provide a framework for encompassing the multi-layered, interactive dynamics of a more complex and comprehensive model. For example, from a cultural perspective, it is important to become familiar with, understand, and respect the beliefs and actions of clients before attempting to change them (Corey, 2009). Due to its strong behavioural and cognitive-behavioural foundation, my theory of counselling takes a relatively structured, pedantic, and controlling stance, where the counsellor leads the therapeutic process. Although the client-counsellor relationship is collaborative, it is not equal (Corsini & Wedding, 2008). This may serve to disenchant clients who are seeking a less directive approach.

RUNNING HEAD: My Counselling Theory

21

This approach also does not directly address the emotional component of the presenting problem. Rather, it indirectly addresses feelings by targeting thinking processes, which in turn, when corrected, will theoretically influence affect. Finally, my theoretical approach does not adequately account for, or is limited in its ability to address significant psychiatric conditions such as schizophrenia, for example. Summary and Personal Reflections My philosophical orientation is strongly influenced by the behavioural and cognitivebehavioural approaches. These approaches form the basis of my theoretical approach largely because I value the heavy emphasis on rigorous scientific procedures that stress replication, empiricism, and evidence-based practice. I am also drawn to the manner in which behavioural and cognitive-behavioural approaches explicitly outline and define treatment goals, in collaboration with the client. Involvement of the client, at least on some level in the therapeutic process, is crucial to therapeutic success in my opinion because it promotes active engagement. Engagement leads to a sense of ownership in resultant outcomes, and therefore promotes higher levels of motivation. I also value the relative balance of emphasis on environmental and mediational factors. I believe firmly that we are both a product of our environment, and producers of our environment. While by no means perfect, the approach offers logical, applicable strategies that remain effective across a wide variety of applications. Furthermore, results are attained within a relatively short period of time, generally, thus making the approach widely applicable. I believe that human development is mediated by an immeasurable number of factors. We are extremely complex, and no single theoretical orientation can adequately account for the major themes associated with our development. My involvement in this class has forced me to

RUNNING HEAD: My Counselling Theory

22

consider alternate theoretical perspectives that I would not have otherwise considered as a means of rationalizing developmental processes that cognitive or behavioural theories cannot explain. While I remain biased toward social learning theory, for example, I have become increasingly drawn to multidimensional theories that promote an integrationist perspective. I consider Bronfenbrenners bioecological model to be superior to social learning theory because it takes cultural, religious, biological and other less obvious variables into account, in conjunction with more obvious variables traditionally linked to the cognitive-behavioural orientation: environment, cognition, perception, judgment, etc. I believe that therapy should be goal-oriented. This is a major highlight of the two theoretical perspectives upon which my theory is based. I have realized that taking an individualized approach to treatment doesnt necessarily entail utilizing techniques limited to only one or two approaches. In fact, an integrationist approach advocates for responsible use of a multitude of approaches, where appropriate. It is important however to note that integrative practitioners must have in-depth knowledge about each theory prior to incorporating them into an intervention plan (Corey, 2001). The counsellor must consider both the compatibility of techniques being combined as well as the suitability of the technique with the particular client and the current issue being addressed (Corey, 2001). In reviewing the four major perspective of development across the lifespan, I have also come to realize, more than ever, each extreme within the respective developmental perspective: nature/nurture, critical periods/plasticity, continuity/discontinuity, and activity/passivity; represents a continuum of rather than an absolute truth in and of itself, as it pertains to major themes within human development. This has led me to the belief that there are elements of truth within all theoretical models of counselling, and as such, the best counsellor is one who remains

RUNNING HEAD: My Counselling Theory

23

open to considering aspects of each theory as a means of truly individualizing treatment to meet the needs of the client. Today, as I approach the end of this Human Development class, I have a better appreciation of the value of keeping an open mind as it pertains to various options available to me as a counsellor. Although my personal history has inevitably shaped my thinking in this regard, I recognize and value the perspectives and strengths that many alternate treatment philosophies offer. In particular, I am much more inclined to consider an eclectic approach to counselling than I ever have been. Furthermore, I have a deeper understanding of the social, systemic and developmental factors that impact human development, and this has prompted me to consider old and familiar problems from a new vantage point.

References Addison, J. T. (1992). Urie Bronfenbrenner. Human Ecology, 20(2), 16-20.

Anderson, S.R., Taras, M., & Cannon, B.O. (1996). Teaching new skills to young children with autism. In C. Maurice (Ed.), Behavioral intervention for young children with autism (pp. 181-193). Baer, D.M., Wolf, M.M., & Risley T.R. (1968). Some current dimensions of applied behaviour analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 1, 91-97. Broderick, P.C., & Blewitt, P. (2010). The life span (3rd ed.). Pearson, Upper Saddle New Jersey. Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development. Harvard University Press. River,

Cooper, J.O., Heron, T.E., & Heward, W.L. (1987). Applied behaviour analysis. Columbus, OH: Merrill.

RUNNING HEAD: My Counselling Theory Corey, G. (2009). Theory and practice of counseling and psychotherapy (8th ed.). Belmont: Brooks/Cole.

24

Crick, N. R., & Dodge, K. A. (1994). A review and reformulation of social informationprocessing mechanisms in children's social adjustment. Psychological Bulletin, 115(1), 74101. Dattilio F.M. (2000). Cognitive-behavioral strategies. In J. Carlson & L. Sperry (Eds.), therapy with individuals and couples (pp. 33-70). Phoenix, AZ: Zeig, Theisen. Dodge, K. A. (1980). Social cognition and children's aggressive behavior. Child Development, 51(1), 162170. Griffiths, D., Gardner, W., & Nugent, J., (1998) Behavioural Supports: Individual Centred Interventions. 1st Ed. NADD Press, Kingston, New York. Griffiths, D., & Hingsburger, D., (1991). OPTIONS: A Community Based Approach for Direct Care Staff. York Behaviour Management Services, Richmond Hill, ON. Brief

Tucker &

Gresham, F. M. & Lochman, J.E. (2009). Methodological issues in research using cognitive-behavioral interventions. In M.J. Mayer, R. Van Acker, J.E. Lochman, & F.M. Gresham (Eds.), Cognitive-behavioral interventions for emotional and (pp. 58-81). New York, NY: The Guilford Press. Kazdin, A.E. (1978). History of behaviour modification: Experimental foundations of contemporary research. Baltimore: University Park Press. Kazdin, A.E. (2001). Behavior modification in applied settings (6th ed.). Pacific Grove, Brooks/Cole. CA: behavioral disorders

RUNNING HEAD: My Counselling Theory

25

Lazarus, A.A. (2000). Multimodal strategies with adults. In J. Carlson & L. Sperry (Eds.), Brief therapy with individuals and couples (pp. 106-124). Phoenix: Zeig & Tucker. Mackenzie, B., Restoule, S., & Veleno, P. (2012). Exploring depression from competing perspectives: Nature, nurture and an integrative approach. Unpublished manuscript.

Paquette, D. & Ryan, J. (July 12, 2001). Bronfenbrenners Ecological Systems Theory. In undefined. Retreived April 2, 2012, from http://pt3.nl.edu/paquetteryanwebquest.pdf

Romanczyk, R.G. (1996). Behavioral analysis and assessment: The cornerstone to effectiveness. In C. Maurice, G. Green, & S. C. Luce (Eds.), Behavioral intervention for young children with autism: A manual for parents and professionals (pp. 195-217). Austin, TX: PRO-ED. Sinclair, C., & Pettifor, J. (Eds.). (2001) Companion manual to the Canadian code of for psychologists, third edition. Ottawa: Canadian Psychological Association. Truscott, D., & Crook, K.H. (2004). Ethics for the practice of psychology in Canada. Edmonton: The University of Alberta Press. Upah, K. R. F., & Tilly, W. D., III. (2004). Best practices in designing, implementing, evaluating quality interventions. In A. Thomas & J. Grimes (Eds.), Best psychology IV (pp. 483501). Bethesda, MD: National and ethics

practices in school

Association of School Psychologists.

Watson, D.L., & Tharp, R.G. (2007). Self-directed behavior: Self-modification for personal adjustment (9th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth. Wilson, G. T. (2008). Behaviour therapy. In R. J. Corsini & D. Wedding (Eds.), Current

RUNNING HEAD: My Counselling Theory psychotherapies (9th ed.) (pp. 235-275). Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole, Cengage Learning.

26

You might also like

- Jkahn - BMP - RevisedforschoolportfolioDocument9 pagesJkahn - BMP - Revisedforschoolportfolioapi-163017967No ratings yet

- CR - Success StoryDocument13 pagesCR - Success Storyapi-163017967No ratings yet

- Kitz - Transition Plan - 2ndrevisedforschoolportfolioDocument12 pagesKitz - Transition Plan - 2ndrevisedforschoolportfolioapi-163017967No ratings yet

- Assessment Plan - Case Study 1 - Veleno - Apsy693 71Document7 pagesAssessment Plan - Case Study 1 - Veleno - Apsy693 71api-163017967No ratings yet

- Pats Resume - Portfolio - 2012Document6 pagesPats Resume - Portfolio - 2012api-163017967No ratings yet

- Intervention Plan Final - Janssen Southworth Veleno - ModifiedDocument30 pagesIntervention Plan Final - Janssen Southworth Veleno - Modifiedapi-163017967No ratings yet

- KP Psyed RPT Jan 31st 2011 - RevisedforportfolioDocument17 pagesKP Psyed RPT Jan 31st 2011 - Revisedforportfolioapi-163017967No ratings yet

- Jkahn - Bar - RevisedforschoolportfolioDocument6 pagesJkahn - Bar - Revisedforschoolportfolioapi-163017967No ratings yet

- Ethics 5 - Vulnerable PopulationsDocument21 pagesEthics 5 - Vulnerable Populationsapi-163017967No ratings yet

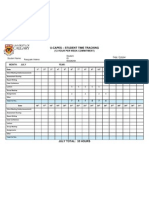

- U-Capes - Student Time Tracking: (12 Hour Per Week Commitment)Document6 pagesU-Capes - Student Time Tracking: (12 Hour Per Week Commitment)api-163017967No ratings yet

- Ethics Assignment 2 - Final Version - Janssen and VelenoDocument11 pagesEthics Assignment 2 - Final Version - Janssen and Velenoapi-163017967No ratings yet

- Janssen Veleno Assignment 3Document12 pagesJanssen Veleno Assignment 3api-87386425No ratings yet

- Parental Discipline and The Use of Aversive Procedures - VelenoDocument23 pagesParental Discipline and The Use of Aversive Procedures - Velenoapi-163017967No ratings yet

- PatvelenocertificateDocument1 pagePatvelenocertificateapi-163017967No ratings yet

- History of Inclusive Education - Final Draft - VelenoDocument19 pagesHistory of Inclusive Education - Final Draft - Velenoapi-163017967No ratings yet

- Final Copy - Review of Fasd Paper - ModifiedDocument9 pagesFinal Copy - Review of Fasd Paper - Modifiedapi-163017967No ratings yet

- Resources Assignment - VelenoDocument26 pagesResources Assignment - Velenoapi-163017967No ratings yet

- Veleno - Letter of Intent - Final Draft 2Document12 pagesVeleno - Letter of Intent - Final Draft 2api-163017967No ratings yet

- Vineland-Ii Presentation - Monique and Pat - Final VersionDocument22 pagesVineland-Ii Presentation - Monique and Pat - Final Versionapi-163017967No ratings yet

- Smith-Veleno - Native Tendencies Paper - Rev - ModifiedDocument15 pagesSmith-Veleno - Native Tendencies Paper - Rev - Modifiedapi-163017967No ratings yet

- Impact of Ibi Paper - Veleno - Final Draft - ModifiedDocument22 pagesImpact of Ibi Paper - Veleno - Final Draft - Modifiedapi-163017967No ratings yet

- Homogeneity of Variance TutorialDocument14 pagesHomogeneity of Variance Tutorialapi-163017967No ratings yet

- Ed Interventions For Children With Tbi - VelenoDocument22 pagesEd Interventions For Children With Tbi - Velenoapi-163017967No ratings yet

- Exam Answers - Veleno - ModifiedDocument10 pagesExam Answers - Veleno - Modifiedapi-163017967No ratings yet

- Vineland-Ii Review - VelenoDocument14 pagesVineland-Ii Review - Velenoapi-163017967100% (1)

- Veleno - Autism Intervention and Best Practices - RevmodDocument19 pagesVeleno - Autism Intervention and Best Practices - Revmodapi-163017967No ratings yet

- Exam - Reports - Draft - Veleno - Storm - Final VersionDocument13 pagesExam - Reports - Draft - Veleno - Storm - Final Versionapi-163017967100% (1)

- Ctopp Presentation - Second Version - ModifiedDocument22 pagesCtopp Presentation - Second Version - Modifiedapi-163017967No ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Inside Reading Answer Key Unit 2: Your Attention, PleaseDocument3 pagesInside Reading Answer Key Unit 2: Your Attention, PleaseMohamad SamaeiNo ratings yet

- Carl Roger's Theory of Fully Functioning PersonDocument19 pagesCarl Roger's Theory of Fully Functioning Personbabitha sujannaNo ratings yet

- Intercultural ManagementDocument9 pagesIntercultural Managementwiam haroualNo ratings yet

- Kant - A Guide For The Perplexed - TK Seung PDFDocument218 pagesKant - A Guide For The Perplexed - TK Seung PDFNicolasRiveraNo ratings yet

- Webinar On CVIDocument59 pagesWebinar On CVIKriti ShuklaNo ratings yet

- Neurourbanism 1Document20 pagesNeurourbanism 1Marco Frascari100% (1)

- REVIEWERDocument2 pagesREVIEWERlouisekevin belenNo ratings yet

- Business Communication - I BBA LM I BBA LM 1st YearDocument5 pagesBusiness Communication - I BBA LM I BBA LM 1st YearSriparna ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- Year 1 RPH 2020 .. Bengkel PAK21Document2 pagesYear 1 RPH 2020 .. Bengkel PAK21PARAMISVARI RAMA NAIDUNo ratings yet

- Design Process & Strategic Thinking in Architecture: March 2016Document3 pagesDesign Process & Strategic Thinking in Architecture: March 2016Jubayer AhmadNo ratings yet

- Top-down bottom-up lesson analyzes news reportsDocument20 pagesTop-down bottom-up lesson analyzes news reportsKasia MNo ratings yet

- Swun Math 4 30Document3 pagesSwun Math 4 30api-245889774No ratings yet

- Unit 3 Pragmatics & SociolinguisticsDocument16 pagesUnit 3 Pragmatics & SociolinguisticsLuna SchneiderNo ratings yet

- Profundity ExplanationDocument11 pagesProfundity Explanationapi-239340617No ratings yet

- Chapter 5 - Employee Testing - SelectionDocument24 pagesChapter 5 - Employee Testing - SelectionNadeem KianiNo ratings yet

- PPT-ISYS6312-PPT03-W3 R2206 BinusDocument40 pagesPPT-ISYS6312-PPT03-W3 R2206 BinusTiara Eka DeliyaNo ratings yet

- Billy Madison Movie ReviewDocument4 pagesBilly Madison Movie Reviewapi-550030025No ratings yet

- Remedial Instruction in LISTENINGDocument17 pagesRemedial Instruction in LISTENINGJane Magana100% (3)

- CBSE Class 12 Unseen Passage Factually ExplainedDocument4 pagesCBSE Class 12 Unseen Passage Factually ExplainedAnimeNo ratings yet

- Baghdad University Architecture Department Environmental DeterminismDocument10 pagesBaghdad University Architecture Department Environmental DeterminismEntisar AlhiloNo ratings yet

- A Study On Emotional Quotient Vs Intelligence QuotientDocument4 pagesA Study On Emotional Quotient Vs Intelligence Quotientkxdhnjkbnlkzdbgdjkb;kvjszbd100% (1)

- English Lesson Gets ActiveDocument3 pagesEnglish Lesson Gets ActiveWayumie RosleyNo ratings yet

- Hepper2015self EsteemencyclopediaofmentalhealthchapterDocument14 pagesHepper2015self EsteemencyclopediaofmentalhealthchapterAlien BoyNo ratings yet

- Tutorial-Draw and Teach With Stick FiguresDocument11 pagesTutorial-Draw and Teach With Stick FiguresJaimeRodriguez100% (1)

- DM Direct MethodDocument4 pagesDM Direct MethodNgọc Anh Đỗ PhạmNo ratings yet

- Competitive Reflections: Adapted From T. Orlick, Psyching For Sport (Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 1986), 17-18Document3 pagesCompetitive Reflections: Adapted From T. Orlick, Psyching For Sport (Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 1986), 17-18Chris BartonNo ratings yet

- Reflection Paper On How Art Made The World - More Human Than HumanDocument4 pagesReflection Paper On How Art Made The World - More Human Than HumanMarcell YasayNo ratings yet

- Divergent Thinking and Risk Taking WorkshopDocument20 pagesDivergent Thinking and Risk Taking WorkshopAurora RinaldiNo ratings yet

- January - March: Bi 1.0 Listening and Speaking SkillsDocument4 pagesJanuary - March: Bi 1.0 Listening and Speaking SkillsNalynhi lynhiNo ratings yet

- Assessment CommentaryDocument7 pagesAssessment Commentaryapi-390728855No ratings yet