Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Committee 3: Diagnostic Terminology: Background

Committee 3: Diagnostic Terminology: Background

Uploaded by

Daniel KurtyczOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Committee 3: Diagnostic Terminology: Background

Committee 3: Diagnostic Terminology: Background

Uploaded by

Daniel KurtyczCopyright:

Available Formats

Committee 3: Diagnostic Terminology

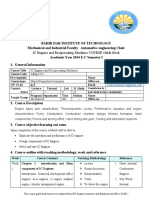

Members: 1) Martha Pitman, MD (Chair) Cytopathologist MGH, HMS 2) 3) 4) 5) 6) 7) 8) 9) Barbara A. Centeno, MD Cytopathologist H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute, Tampa , FL Lester Layfield, MD Cytopathologist University of Utah Muriel Genevay, MD Cytopathologist - Hospital de Pathologie Clinique, Geneva, Switzerland Syed Ali, MD Cytopathologist Johns Hopkins Medical Center C. Max Schmidt, MD Surgeon Indiana University Carlos Fernandez-del Castillo, MD Surgeon- MGH, HMS William Brugge, MD Gastroenterologist MGH, HMS Volkan Adsay, MD Surgical Pathologist Emory University Hospital

10) David Klimstra, MD Surgical Pathologist Memorial Sloan Kettering

Proposed Terminology Scheme for Pancreatobiliary Cytology

Background Early detection of cancer whether it is malignancy of the ductal, acinar, or neuroendocrine system is the key to survival for patients. With the increased use of EUS and FNA for the evaluation of pancreatobiliary lesions, coupled with our improved understanding of premalignant lesions and the evolving management algorithm for patients with pancreatic cysts, it is clear that cytopathologists play a very important role in the diagnosis and management of patients with pancreatic mass or cystic lesions and pancreatobiliary strictures. The indication for FNA is the evaluation of a solid or cystic mass lesion. EUS guided FNA of the pancreas is a technically difficult procedure and yields aspirates that are diagnostically challenging. Thus, the sensitivity of this procedure is variable, averaging 80% but ranging from 60% to 100% Sensitivity of the procedure can increase overtime, reflecting increasing experience with this technique. The specificity of diagnosis in the setting of a solid pancreatic mass is greater than 90%. The adequacy and sensitivity rates are generally higher when rapid onsite assessment is performed. It is difficult to compare the sensitivity of FNA among studies because of the wide variability in factors such as needle size, operator experience, and radiological equipment. Additionally, the atypical and suspicious categories have been

variably interpreted as negative or positive for the purposes of statistical analysis. The inaccuracies of pancreatic FNA are primarily due to false negative reports. The sensitivity for cystic neoplasms is lower than that for solid neoplasms largely due to the low cellularity of most of these cystic lesions and the lack of clear criteria for interpretation. The most frequent indication for biliary brushing is the presence of a stricture or obstruction of the biliary tree. Endobiliary brushing is currently the preferred method of sampling the biliary system in cases of stricture or obstruction, since the preparation is usually rich in cells and cell preservation can be excellent if the specimen is fixed immediately and the cells are spared preparation artifact Prospective studies document a higher level of sensitivity of biliary brushings over exfoliative cytology for the detection of biliary carcinoma. Furthermore, the sensitivity of bile duct brushings has been shown to increase after repeated attempts In fact the probability of a patient having a carcinoma is less than 6% after three negative brushings. Predictors of positive yield include older age, mass size>1 cm, and stricture length of >1 cm. Most false negative interpretations occur from sampling error, which occurs most often when the tumor does not invade biliary mucosa, or when tumor cells are entrapped in sclerotic desmoplastic stroma. Poor visualization of the area by the endoscopist may also negatively impact sampling. Interpretation errors (17%) and technical errors (17%) are the second most frequent causes of false negative results. Most interpretation errors result from under-interpretation of adenocarcinoma due to the difficulty of distinguishing adenocarcinoma from reactive changes, often due to the underlying disease process or the result of an indwelling stent. Poor sample fixation and preparation also contribute to under-interpretation of adenocarcinoma . A necrotic or inflammatory background may obscure malignant cells and may be yet another factor contributing to under-diagnosis. The converse is also true: reactive changes can mimic adenocarcinoma, and lead to a false positive interpretation. Degeneration of malignant cells is also a source of false negatives. False positives commonly result from over-interpretation of reactive and degenerative changes. Another important pitfall are dysplastic but non-invasive neoplasms of the ampulla or bile ducts. A standardized nomenclature system that provides intra- and interdepartmental guidance for diagnosis that correlates with management recommendations is imperative for both FNA of pancreatic masses and cysts and brushing cytology of pancreatobiliary strictures. Below is a proposed terminology scheme with 6 categories including a category Neoplastic that is divided into clearly benign neoplasms and other neoplasms with less definitive biologic behavior predictable by cytological features. I. Nondiagnostic Insufficient cellular material for diagnosis II. Negative Pancreatitis-acute, chronic, autoimmune Pseudocyst Lymphoepithelial cyst

Spenule/accessory spleen III. Atypical Mild-moderate cellular atypia, NOS Mucinous ductal epithelium with and mild-moderate nuclear atypia IV. Neoplastic Benign Serous cystadenoma Mature teratoma Schwannoma Other Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor Solid-pseudopapillary neoplasm Mucinous cyst (IPMN or MCN), not otherwise specified (NOS), e.g. only thick, colloid-like mucin or elevated CEA or positive KRAS, if known Mucinous cyst (IPMN or MCN) with low-grade atypia/dysplasia Mucinous cyst (IPMN or MCN) with high-grade atypia/dysplasia GIST V. Suspicious Severe cellular atypia, suspicious for invasive ductal carcinoma or other high-grade malignant neoplasm, or Solid cellular smear pattern without diagnostic cytological features or tissue available for confirmatory immunohistochemistry supportive of a specific neoplasm such as PanNET or SPN. VI. Positive/Malignant Adenocarcinoma of the pancreatobiliary ducts, and variants Acinar cell carcinoma High-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma (small and large cell type) Pancreatoblastoma Lymphoma Metastases Category I. Non-Diagnostic Background: Non-diagnostic specimens may be due to technical or sampling issues that preclude the pathologist from providing any useful information from the biopsy relative to the lesion sampled. The clinical and imaging context should be taken into consideration. The absence of "epithelial cells" in the sample does not necessarily make a specimen non-diagnostic. For example, pseudocyst fluid or a mucinous cyst

with only thick colloid-like mucin, or a cyst with elevated CEA, both findings sufficient to support an interpretation of a mucinous cyst.

Definition: A non-diagnostic cytology specimen is one that provides no diagnostic or useful information about the lesion sampled. Any cellular atypia precludes a nondiagnostic report.

Cytological Criteria: Non-Diagnostic Preparation artifact precludes evaluation of the cellular component Obscuring artifact precludes evaluation of the cellular component Gastrointestinal epithelium only Normal pancreatic tissue elements in the setting of a clearly defined

solid or cystic mass by imaging Acellular aspirates of a solid mass or pancreatobiliary brushing Acellular aspirate of a cyst without evidence of a mucinous etiology

such as thick colloid-like mucus, elevated CEA or KRAS mutation (See Section IV)

Category II. Negative Background: A negative cytology sample is synonymous with the absence of malignancy and any cellular atypia. A negative cytology interpretation without a diagnosis of a specific condition such as chronic pancreatitis or pseudocyst is not synonymous with a benign lesion. A descriptive negative interpretation implies that the sample is adequately cellular and that no cytological atypia is identified in the cells evaluated. This includes the presence of normal pancreatic tissue in the appropriate clinical setting such a vague fullness on imaging and no distinct mass lesion. The false negative rate of an FNA of a solid mass lesion averages 15%, and in the setting of a

clinically and radiologically suspicious mass with a presumed diagnosis of ductal adenocarcinoma, such an aspirate is presumed to be a false negative sample. The false negative rate for aspirates of cystic lesions is as high as 60% due to acellular or scantily cellular samples, in addition to the lack of experience in interpreting these lesions outside of major academic hospital settings. The false negative rate for the interpretation of pancreatobiliary brushing samples is also high due to the difficulty in obtaining diagnostic tissue that is often subepithelial or entrapped in desmoplastic stroma, coupled with the high threshold for a malignant interpretation due to the typical clinical setting of inflammation and/or biliary stenting.

Definition: A negative cytology sample is one that contains adequate cellular and/or extracellular tissue to evaluate or define a non-neoplastic lesion that is identified on imaging.

Cytological Criteria: Benign Pancreatobiliary Tissue o Acinar epithelium: High cellularity

o polygonal cells with basal nuclei and apical granular cytoplasm present mostly in grape-like acinar structures singly or attached to connective tissue fragments; cellularity may be high o o o single cells may be present nucleoli may be inconspicuous or quite prominent naked acinar cell nuclei are few Ductal epithelium:

o flat, honeycombed sheets of non-mucinous glandular epithelial cells in an evenly spaced, lattice-like arrangement with o round to oval uniform, evenly spaced nuclei smooth nuclear membranes, even chromatin and inconspicuous nucleoli orderly, polarized picket-fence arranged cells with

basal nuclei non-mucinous columnar cytoplasm

o Even chromatin or open vesicular chromatin with small nucleoli indicative of reactive changes or repair o o o goblet cells are rare mitoses are absent or rare and normal Islet cells: generally not recognized

o May be present in small clusters of small uniform polygonal cells in a background of acinar and/or ductal epithelial cells Bile in biliary brushing specimens

Cytologic criteria - Gastrointestinal Contaminants o o o o o o o o o Duodendal epithelium Large, flat sheet of non-mucinous, evenly spaced epithelial cells with Scattered goblet cells [fried egg appearance on Interspersed lymphocytes Brush border on luminal edge of cytoplasm Gastric epithelium Small groups of mucinous, evenly spaced epithelial cells with Apical cytoplasmic mucin No goblet cells, lymphocytes or brush border Papanicolaou stain]

Cytological Criteria: Acute Pancreatitis

tissue and

Dominance of neutrophils, fragments of granulation

aggregates of necrotic fat and foamy macrophages. Granulation tissue is composed of reactive fibroblasts endothelial cells and inflammatory cells. The endothelial cells frequently form interconnecting tubular (capillary) structures. In later stages of acute pancreatitis, increasing numbers of lymphocytes and plasma cells are seen. The amount of epithelial tissue present is variable and necrotic ductal and acinar epithelial groups may be present. Atypia of the epithelial component is usually minimal and mitotic activity is generally restricted to the granulation tissue component. Cytological Criteria: Chronic Pancreatitis stages. Chronic inflammatory cells as well as ductal, acinar and islet cell epithelium, but the acinar component decreases with late stages Fragments of fibrous tissue that may appear disorganized with spindle cells running in irregular interlacing groups. Within these tissue fragments, little inflammation is apparent and mitotic figures are not seen. necrosis Islet cells, singly and even intact islets of Langerhans that are tightly cohesive with well-delineated tissue fragment edges. Ductal epithelium in sheets and clusters with reactive nuclear changes +/- some loss of the normal honeycomb monolayer sheet-like pattern, but no significant nuclear atypia Ductal epithelium may show squamous metaplasia resulting in an appearance of squamous eddies. Cell debris (necrotic fat) and calcifications, but no coagulative cellular Variable cellularity, often scanty, but may be highly cellular in early

Cytological Criteria: Autoimmune Pancreatitis Pure cytomorphologic analysis cannot definitively diagnose autoimmune pancreatitis but may be sufficient to suggest the diagnosis with the findings below. Flow cytometric analysis for IgG4 may be helpful in confirming the diagnosis Ductal epithelial cells are few to absent but, when present, may show reactive changes and significant atypia; AIP is a source of significant false positive cytological interpretations Conspicuous background of single lymphocytes and/or plasma cells may or may not be present Stromal fragments with high cellularity of mixed inflammatory cells, possibly acinar cells, sometimes obscured by smearing artifact Cytological Criteria: Pseudocyst Mixed inflammatory cells, mostly lymphocytes and histiocytes

Cellular debris with red blood cells, granular necrotic debris and yellow pigment , crystalline debris and calcifications Hemosiderin-laden macrophages No serous or mucinous cyst lining epithelium

Contaminating epithelium from GI tract common, and from the pancreas, occasional Fragments of granulation tissue and fibrous tissue uncommon

Cytological Criteria: Lymphoepithelial Cyst epithelium Abundant anucleated squamous cells and sheets of benign squamous Small mature lymphocytes, may be prominent or sparse +/- histiocytes Plate glass-like cholesterol crystals may be present

Cytological Criteria: Splenule/Accessory Spleen Bloody background

Platelet aggregates dispersed among tissue fragments composed of lymphocytes and endothelial cells. Lymphoid population dominates the smears but is without germinal centers and tingible body macrophages as in a reactive node Lymphoglandular bodies Dendritic cells (CD8+)

Category III. Atypical Background: The interpretation category Atypical represents an ill-defined category with significant interobserver variability often stemming from varying experience in interpreting pancreatic cytology. Also contributing to this interpretation are samples with scant cellularity, poor cellular preservation, and an inflammatory background. This interpretation is used when a cytological specimen contains cellular or extracellular tissue that is beyond recognizable normal tissue components or reactive changes that can comfortably be interpreted as such and thus leading to a negative interpretation. An atypical interpretation does raise the possibility of a neoplasm, but the cytological findings are insufficient to be suspicious for a high-grade neoplasm. Conservative interpretation of diagnostic samples is not uncommon due to the significance of the surgical intervention, often a pancreaticoduodenectomy. Abundant cytoplasmic mucin in pancreatic ducts is an abnormal finding and indicates a neoplastic change. The differential diagnosis for glandular epithelium with mucinous cytoplasm includes pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN), intraductal biliary neoplasia, intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm, mucinous cystic neoplasm and adenocarcinoma. PanIN is not an entity recognized by imaging but it may be a source of atypia in aspirates of solid masses. Gastric epithelial contaminant is another source of mucin containing epithelium that may be confused with ductal epithelium with mucinous metaplasia. Of note, gastric epithelium may demonstrate some of the changes of pancreatic neoplasia, such as nuclear grooves and inclusions, and subtle crowding. Duodenal enterocytes are nonmucinous with a brush border, and, in

addition to this feature, can be recognized by the presence of scattered goblet cells and intraepithelial lymphocytes. Premalignant lesions of the bile ducts have historically been called biliary dysplasia or atypical biliary epithelium. A new consensus classification of Biliary Intraepithelial Neoplasia (BilIN),was published in 2007. This proposal classified BilIN into a three grade classification scheme, similar to that used in other organs such as the pancreas and prostate. The lesions were derived from patients suffering from primary sclerosing cholangitis, choledochal cyst or hepatolithiasis. The histopathological criteria are similar as for other intraepithelial lesions, but the cytopathological criteria of these lesions have not been defined. However, it can be assumed that their cytological features will be similar to what has been described as dysplasia in the biliary tract with grade 1 and 2 lesions causing atypia on bile duct brushings, previously referred to as low grade dysplasia .

Definition: The category of atypical should only be applied when there are cells present with cytoplasmic, nuclear, or architectural features that are not consistent with normal or reactive cellular components of the pancreas or bile ducts, and are insufficient to classify them as a neoplasm or suspicious for a high grade malignancy. The findings do not explain a lesion identified on imaging studies. Follow-up evaluation is warranted.

Cytological Criteria: Atypical Architectural

o Mild disorder of honeycomb pattern with mild nuclear crowding, and touching of the nuclei o o o Pseudostratification of nuclei in on-edge groups with maintenance of polarity Papillary clusters Range of atypia without two distinct groups of ductal cells

o Non-ductal cells (acinar, endocrine, or extra-pancreatic) that are not normal appearing in architecture or morphology but are insufficient in quality or quantity to be suspicious for or diagnostic of a neoplasm o o o o o o o o o o Nuclear Mild anisonucleosis of ductal cells (less than 4 fold; generally 2-fold or less) Nuclear elongation Mild to moderate nuclear hyperchromasia Hypochromasia with subtle nuclear membrane abnormalities Prominent nucleoli Occasional degenerative changes with nuclear pyknosis and karyorrhexis Mitotic activity may be visible, but mitotic figures are few and symmetrical Cytoplasmic Cytoplasmic mucin in ductal type cells Hard, keratinous cytoplasm (not oral or esophageal contamination) Mild increase in nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio of ductal type cells

Category IV. Neoplastic IVA. Neoplastic: Benign Background A common benign neoplasm of the pancreas is the serous cystadenoma. Histologically, serous neoplasms consist of fine fibrous septae surrounded by cuboidal, glycogen-rich cells without atypia. Fibrous septa include numerous small capillary structures. This dense vascularization explains the often hemorrhagic aspect of the cyst fluid as well as the presence of numerous hemosiderin-laden macrophages on cytological preparations. Such macrophages can be observed in up to 63% of cases, whereas they are almost always absent in mucinous cystic neoplasms. Macrophages can, however, only be considered as a surrogate marker of serous cystic neoplasm and cannot be used as a definitive cytological criterion. When coupled with cytological analysis, and with appropriate clinical and imaging features, biological analysis of CEA level, typically less than 5 ng/ml, and amylase levels, typically also very low,

support the diagnosis. Caution must be used because some mucinous cysts have very low CEA levels, and conversely, serous neoplasms can, albeit rarely, present with elevated CEA levels. Other benign neoplasms in the pancreas such as cystic teratoma and schwannoma are extremely rare. Definition: Neoplastic: Benign This interpretation category connotes the presence of a cytological specimen sufficiently cellular and representative, with or without the context of clinical, imaging, and ancillary studies, to be diagnostic of a benign neoplasm. Cytological Criteria: Serous Cystadenoma Paucicellular to acellular specimens Clear to bloody background No extracellular mucin [except for occasional GI contamination] Uniform non-mucinous, cuboidal cells in small clusters that form a flat sheet or small groups Round, central to slightly eccentric nuclei with a smooth nuclear contour, evenly dispersed chromatin and indistinct nucleolus. Scant but visible granular to clear, sometimes finely vacuolated cytoplasm. PAS and PAS-D positivity of the cytoplasm, confirming the glycogenic content [rare to have sufficient cells to make a cellblock for this] Absence of necrosis, atypia or mitoses

Cytologic Criteria: Cystic Teratoma The content of the cyst cavity will vary depending on the nature of the epithelium layering the cyst wall Variable cellularity Sebaceous elements, keratinous debris, respiratory epithelium Nucleated squamous cells that are often accompanied by keratinous debris High grade to malignant component should not be identified for inclusion in this category

Cytologic Criteria: Schwannoma Hypocellular or moderately cellular samples Large, cohesive tissue fragments. Scattered or closely packed tumor spindle cells with poorly defined cell borders. Nuclear palisading. Wavy, ovoid nuclei with a fine chromatin pattern. Fibrillary to myxoid stroma. Mitoses are typically absent. IIIB. Neoplastic: Other Background Not all neoplasms of the pancreas can be categorized as definitively benign or malignant. Aside from the clearly malignant neoplasms like conventional pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and the definitively benign neoplasms like serous cystadenoma, there are neoplasms (Other) that are either preinvasive (IPMN and MCN with low, intermediate or high grade dysplasia) or of low-grade malignant behavior based on preoperative cytological parameters. The cytological features of these neoplasms do not correlate with biological behavior (PanNET and SPN). The same is also true for biliary tract counterparts of these lesions which are now termed intraductal papillary neoplasms of the bile ducts (IPN-B), although previously also called intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms or papillomatosis or papillary cholangiocarcinomas All of these pancreatic tumors are clearly neoplastic and the standard cytological categories of atypical and suspicious for malignancy are categories that connote an indeterminate interpretation that does not provide for a definitive cytological interpretation of the neoplasm which would lead to appropriate patient management and preclude the need for a repeat diagnostic procedure.

Definition: Neoplastic: Other This interpretation category defines a neoplasm that is either premalignant such as IPNB, IPMN or MCN with low, intermediate or high grade dysplasia, or a solid-cellular neoplasm such as well-differentiated PanNET or SPN. While mucinous epithelium in biliary brushing specimens may indeed represent a neoplastic change,

given the lack of evidence-based literature on the cytology, histology and management of these lesions, low-grade mucinous change of biliary epithelium will remain in the atypical rather than neoplastic category. Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumor To be consistent with the new 2010 WHO, the current preferred nomenclature is pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor (PanNET). Synonyms include pancreatic endocrine tumor (PET), pancreatic endocrine neoplasm (PEN) and well-differentiated endocrine carcinoma. With the WHO-2010 the term neuroendocrine carcinoma without the preface welldifferentiated, however, infers either high-grade large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma or small cell carcinoma. The cytological interpretation of PanNET infers a well-differentiated proliferation of the pancreatic endocrine cells creating a mass lesion greater than 0.5 cm that may or may not be functional by producing inappropriate levels of various hormones, and that may or may not demonstrate aggressive features on histological examination. However, it is now widely accepted that PanNETs are all malignant neoplasms, albeit very slow growing, and even curable, if caught at an early stage. Cytological Criteria: Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumor Moderately to highly cellular smears; scant cellularity is common with cystic degeneration Mostly non-cohesive single cells with or without small to medium sized groups or rosettes and clusters of cells +/- vascular network and/or bloody background Monotonous population of small to medium sized polygonal epithelial cells Nuclei are usually bland and uniform, but can be quite atypical and may display significant pleomorphism (endocrine atypia) Cells have round nuclei and generally visibly coarse, stippled, evenly distributed ("salt and pepper") chromatin pattern Nucleoli are usually inconspicuous but occasionally quite prominent Stripped naked nuclei are not uncommon Cytoplasm is relatively scant, and usually dense and eccentric yielding a plasmacytoid appearance (this feature is best appreciated in single cells) Rare variants produce cells with clear, vacuolated cytoplasm or oncocytic cytoplasm Mitotic figures and necrosis are absent to rare Solid-Pseudopapillary Neoplasm Solid-pseudopapillary neoplasm (SPN) is a solid, secondarily cystic lowgrade epithelial neoplasm with established clonal mutations in cancer-associated genes and an ability to metastasize. They typically occur in young females and demonstrate a variably solid and cystic appearance on imaging. Like PanNET, it is a parenchymalrich, stromal-poor proliferation of monotonous cells that belie prediction of the

biological behavior. Although this neoplasm, like PanNET, is considered a low-grade malignancy, it is included in this category to distinguish it from PDAC. Cytologic Criteria: Solid-Pseudopapillary Neoplasm Cellular smear pattern composed of small, uniform cells in cohesive, often branching and papillary cell clusters Background may be clean or filled with hemorrhagic cyst debris laden with foamy histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells Small clusters and single neoplastic cells in the background Individual cells are homogeneous in appearance with little anisonucleosis Nuclei are round to oval with smooth to slightly indented or grooved nuclear membranes Delicate fibrovascular cores with myxoid stroma (Romanowsky stains: magenta colored, metachromatic material; PAS positive, diastase resistant) Zone of cytoplasm often separates the nuclei of the neoplastic cells from the fibrovascular cores Even and finely granular chromatin Inconspicuous nucleoli Cytoplasm is scant to moderate, non-granular to finely granular, and may contain a small perinuclear vacuole or intracytoplasmic hyaline globule No to rare mitotic activity Neoplastic Mucinous Cysts of the Pancreas (Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN) and Mucinous cystic neoplasm (MCN)) The two primary neoplastic mucinous cysts of the pancreas include IPMN and MCN. Understanding the clinical and imaging features of IPMN and MCN is vital to the interpretation of the cytological specimen. Given that the cytological features of these two mucinous cysts are usually indistinguishable for all practical purposes, the cytological features will be presented together. The pathologist should correlate the clinical and imaging features to suggest the most likely specific diagnosis. Management guidelines have evolved over time and have become much more conservative given the prevalence of incidental, asymptomatic cysts identified in the general population and especially in the elderly. MCN, although mostly low grade, are usually identified in young to middle-aged women in the body or tail of the pancreas that can be relatively easily removed with a distal pancreatectomy alleviating the need for expensive, life-long surveillance. Main duct and combined type IPMNs are all removed due to the inherent high risk of malignancy. Branch-duct IPMNs are more often than not low-grade neoplasms identified in the pancreatic head of the elderly with co-morbid conditions making pancreaticoduodenectomy a high-risk procedure greater than the risk of the cyst progressing to malignancy. If a cyst is mucinous and there is no evidence of high-grade dysplasia or carcinoma, then

conservative management is reasonable. The difficult position for the pathologist then becomes grading the epithelium of the cyst. It is quite difficult in other organ systems even on histology to stratify grades into 4 tiers: low, moderate, and severe dysplasia and carcinoma. This difficulty is exponential when interpreting just a few cells that have been degenerating in cyst fluid and that may be associated with GI contamination. A high threshold for malignancy is in order. That being said, recognition of atypical epithelial cells and the distinction from low grade dysplasia is vitally important to recognizing a cyst with high grade atypia that likely corresponds to a cyst with at least moderate dysplasia and in a high proportion of cases, high-grade dysplasia or worse. Resection prior to invasion provides the patient with the best prognosis, and high risk imaging features such as a markedly dilated main pancreatic duct or a mural nodule in a cyst that lead to resection are very often signs of an invasive neoplasm. As such, aspiration of cysts without these features provides the best opportunity to detect early carcinoma. Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm IPMNs are primarily intraductal proliferations of ductal epithelium creating a macroscopic lesion resulting in ductal dilatation, cyst formation and/or a mass lesion. Intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasms are included with IPMN as this neoplasm is not only rare, but would be indistinguishable from most IPMN on cytology. Invasion of the duct or cyst occurs in about one third of resected IPMN, and is most common in IPMN of the main pancreatic duct. There are three main types of IPMN : 1. Main-duct IPMN: Generally associated with diffuse dilatation of the main pancreatic duct of any part or the entire pancreas. The definition of dilatation is variable in the literature. The 2006 Sendai guidelines define it as >6mm, but the new 2012 guidelines define it as 10mm or greater with > 5mm being worrisome. Visualization of mucin extruding from the ampulla on EUS or ERCP is pathognomonic. The epithelial cell type most often associated with main duct IPMN is intestinal type epithelium (MUC 5AC, MUC 2 and CDX2+) which, by definition, is at least intermediate (moderate) dysplasia. Invasive carcinomas most often arising from intestinal type IPMN are colloid carcinomas. 2. Branch-Duct IPMN: Cysts adjacent to a non-dilated main pancreatic duct, most often in the uncinate process, but occurring throughout the pancreas in one or more locations. Imaging features generally depict a thin-walled unilocular cyst that may or may not demonstrate a connection to the pancreatic ductal system. Small "raspberry-like" multiloculated cysts are also typical of BD-IPMN. The cyst lining is most often gastric-foveolar in type, and, although most are low grade, this epithelial cell type can display intermediate and high-grade dysplasia. Invasive carcinomas arising from these cysts tend to be tubular type and have a prognosis similar to conventional pancreatic adenocarcinoma. 3. Combined-type IPMN: Neoplasia involving both the main and branch ducts of the pancreas typically represented on imaging by a dilated main pancreatic duct with one or more branch-duct cysts. Two other epithelial cell types may be seen in IPMN. Pancreatobiliary epithelium is relatively uncommon and, by definition, is equivalent to high-grade dysplasia. Oncocytic epithelium is the least common epithelial cell type, and is also

considered high-grade. Oncocytic type epithelium is distinguished by the moderate amounts of dense, granular, oncocytic cytoplasm. While low-grade gastric-foveolar type epithelium is recognizable, it may not be distinguishable from gastric epithelial contamination in transgastric biopsies. It is generally not possible nor is it important to distinguish the epithelial cell types with intermediate to high-grade dysplasia. Cyst Fluid Analysis Analysis of the cyst fluid from pancreatic cysts is invaluable in accurate classification of the cyst as mucinous or non-mucinous. It is well established that although each lab should establish their own cut-off value, that, CEA levels of ~200 ng/ml is strongly supportive of a neoplastic mucinous cyst. A low CEA level does not exclude a mucinous etiology. In addition, CEA levels do not distinguish between benign and malignant cysts. Amylase levels of cyst fluid are helpful in supporting the interpretation of a pseudocyst as such fluids typically have amylase levels in the thousands, but amylase levels do not distinguish between IPMN and MCN. Serous cystadenomas tend to have both low CEA and amylase levels as do cystic pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Molecular Analysis KRAS testing may supplement CEA as the detection of KRAS supports a mucinous etiology. Although the combination of KRAS, LOH and quality and quantity of DNA correlates with malignancy, a KRAS mutation in and of itself is not specific for malignancy. A recent study of pancreatic cyst fluid has shown that detection of GNAS supports a specific interpretation of IPMN, but does not distinguish pre-malignant from malignant (invasive) IPMN. See the report of Committee 5 for a more detailed discussion of ancillary testing. Mucinous Cystic Neoplasm (MCN) MCN of the pancreas is typically a multiloculated, mucin-producing epithelial neoplasm with subepithelial ovarian-type stroma that in almost all cases does not communicate with the pancreatic ductal system and in almost all cases occurs in women. Like IPMN, these neoplasms are stratified by the degree of cytological and architectural atypia into low-grade, intermediate-grade and high-grade dysplastic, premalignant (non-invasive neoplasms) and invasive carcinomas (invasive mucinous cystadenocarcinoma). The invasive carcinomas are usually tubular type, but rare carcinomas such as undifferentiated carcinoma with osteoclast-type giant cells may also be seen. . A similar neoplasm occurs in the biliary tract. The cytological features will be similar to its pancreatic counterpart. Approach to the Cytological Analysis of Pancreatic Cysts The cytopathologists approach to the interpretation of a pancreatic cyst should be to address two basic questions. 1: Is the cyst mucinous or non-mucinous; and 2: Is the cyst high-grade or not? Malignant is defined as unequivocal features of

adenocarcinoma (See section on Positive for Malignant Cells). Atypia less than overtly malignant is included in this category of Neoplastic: Other. To answer the first question of a mucinous etiology, the first clue may come from the gastroenterologist who describes thick, viscous or white, sticky fluid upon aspiration. This type of fluid is generally thick enough to make a direct smear. Thinner fluids are best processed as a cytospin in order to capture all of the cells and to preserve the characteristics of the cyst fluid. Placing the cyst fluid in a preservative attenuates the viscosity of the fluid and may make thin mucin difficult or impossible to appreciate. Contamination of the specimen with mucin from the gastrointestinal tract is also a consideration. Thick, colloid-like mucin is neoplastic (with rare exception such as in a gastrointestinal duplication cyst), and mucin with evidence of cellular cyst debris also supports origin from the cyst and not the GI tract. Conversely, thin mucous with naked grooved nuclei evoke GI contamination. Special stains for mucin may be helpful but should be interpreted with caution. A mucicarmine or Alcian blue positive thin film of a cytospin or thick wavy wisps of mucoid fluid that stains positively without significant GI epithelial contamination are stain outcomes that support a mucinous etiology. Negative mucin stains do not exclude a mucinous cyst. CEA elevation or detection of a KRAS mutation may be necessary to support a mucinous etiology, but, a non-elevated CEA or absent KRAS mutation does not exclude a mucinous cyst. To answer the second question of high-grade, an evaluation of the epithelial component is required. The criteria for overt malignancy are outline below. Less than overt malignancy is interpreted as either low grade or high-grade atypia as the accuracy in distinguishing intermediate (moderate) from high-grade dysplasia is difficult if not impossible, and the criteria to do so with any accuracy has not been established. GI contaminating epithelium needs to be recognized as such (see criteria under category I) Both mucin production and epithelial cells are not required for the diagnosis of a mucinous cyst. The aspirates of some mucinous cysts are acellular but are clearly mucinous from the visible thick, colloid-like extracellular mucin, elevated CEA or KRAS mutation. Similarly, a cyst fluid with high-grade mucinous epithelial dysplasia or carcinoma may not demonstrate extracellular mucin or an elevated CEA. Approach to The Cytological Evaluation of Biliary Tract Cysts The approach to evaluating cysts arising in the biliary tract has not been as formally studied as those of the pancreas. However, it can be surmised that IPN-B and MCN-B will have similar cytological features on aspiration. The role of ancillary studies in these cysts, such as measurement of CEA, is not established. Cytological Criteria: Mucinous Cysts o Mucin Production Established Thick, colloid-like extracellular mucin Cellular or inflammatory debris within the mucin

o Thin mucin covering the slide confirmed with Special stains for mucin (mucicarmine or alcian blue pH2.5) OR Elevated CEA (192 ng/ml is ~ 85% accurate) OR KRAS mutation And/OR Neoplastic Epithelial Cells identified o Low grade mucinous epithelium ,e.g. low-grade atypia (gastrointestinal epithelium or low grade to intermediate grade dysplasia) scant cellularity single cells, small clusters and flat sheets of bland glandular epithelial cells cytoplasmic mucin visible on routine light microscopy nuclei round and regular with even chromatin and inconspicuous to occasionally prominent nucleoli honeycomb sheet or on edge with basally located nuclei and apical cytoplasmic compartment the cells may be indistinguishable from gastric contamination few to small single cells or groups with bland nuclei, no nuclear membrane abnormalities but increased N/C ratio +/- cytoplasmic vacuoles muciphages (foamy histocytes) o High grade epithelium, e.g. high-grade atypia (at least high-grade dysplasia/carcinoma in-situ, but quality and quantity of atypia is insufficient for diagnosis of adenocarcinoma) Scant to high cellularity Epithelial cells that have lost the benign features of low grade dysplasia Small to large clusters and single cells 2-4 cell tight buds of cells 3-dimensional architecture papillary arrangement (supports IPMN) single cells High nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio Variable amounts of cytoplasm with and without visible mucin or vacuoles Nuclear membrane irregularity mild to moderate Coarse chromatin Variable nucleoli Cyst fluid with necrosis or acute inflammation scant to moderate . Intraductal Papillary Neoplasm of the Bile Ducts (IPN-B)

Intraductal papillary neoplasm of the bile ducts shares many clinical and pathological features with IPMN of the pancreas (IPMN-P). It is a neoplastic proliferation growing within the bile ducts composed of a papillary proliferation of mucin containing neoplastic cells that may occur anywhere in the ductal system. It progresses from low, to high grade and eventually invasive carcinoma, just as IPMN-P does. Gastric, pancreatobiliary, intestinal and oncocytic types subtypes have been described, but show a different distribution than observed in IPMN-P. These are more likely to be sampled by brushing cytology than by fine needle aspiration. When they present as cystic masses, they may be aspirated, and the cytological features of aspiration cytology will be similar to those of IPMN-P. The cytological features of brushing cytology for IPN-B are described here. While there are no prospective or retrospective reports, these features are extrapolated from the histopathological features and are similar to what is encountered in brushing cytology of IPMN-P. Cytology Groups with crowding and overlapping Papillary formations, or columnar cells seen on edge Elongated nuclei in lower grade dysplasia Larger, vesicular nuclei in higher grade dysplasia Mucinous cytoplasm which may vary in appearance depending on the degree of differentiation Oncocytic cytoplasm in the oncocytic variant Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor (GIST) GISTs are very rare as a primary pancreatic neoplasm (extra-gastrointestinal stroma tumor, EGIST), however, they commonly occur in a peripancreatic location such as the omentum, mesentery, duodenum and stomach, thus mimicking a primary pancreatic neoplasm at times. GIST are spindle cell or epithelioid mesenchymal neoplasms with differentiation along the lines of the interstitial cell of Cajal that usually expression c-kit protein (CD117) and DOG1 by immunohistochemistry. There is variable expression of alpha-smooth muscle actin and CD34, and essentially no reactivity for desmin. As with all spindle cell lesions, procuring cell-blocks on such specimens will facilitate a definitive diagnosis. Cytological Criteria: Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor o o o o o Spindle cell proliferation with cellularity scant to moderate possible hemorrhagic background uniform ovoid nuclei with tapered ends palisading nuclei, delicate cytoplasmic processes with indistinct cell borders

o o o o

perinuclear vacuoles not usually identified very rare mitoses possible Epithelioid cell proliferation with cellularity scant to moderate polygonal cells of small to medium size Round, usually bland nuclei Even chromatin (not stippled and coarse like a neuroendocrine tumor) Variable nucleoli Visible cytoplasm that may be dense or contain perinuclear vacuoles

IV. Suspicious for Malignancy Background The cytological interpretation category of suspicious for malignancy generally refers to pancreatic adenocarcinoma, but may be used with any malignant neoplasm. Suspicious for is NOT diagnostic of, and clinical and radiological information must be correlated with the suspicious cytological findings to justify surgical intervention. Like the atypical interpretation category, suspicious for malignancy suffers from significant interobserver variability often stemming from varying experience of the pathologist in interpreting pancreatic cytology. Due to the high threshold of a malignant interpretation, and thus the low false positive rate of pancreatic cytology, many samples are conservatively interpreted and may benefit from a second opinion by an experienced pancreatic cytopathologist to save the patient the potential of a repeat diagnostic procedure. Although the cytologic criteria for pancreatic adenocarcinomas, neuroendocrine tumors, lymphomas, and metastases are well established (see below), cytologists are faced with three major challenges when dealing with fine needle aspiration specimens of the pancreas. The first challenge is the very high level of differentiation of certain pancreatic adenocarcinomas that may harbor very subtle cytologic abnormalities. The second challenge is scant cellularity. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma induces a tumorassociated sclerotic response that may contribute to this sparse cellularity. The third problem that cytologists must address is gastrointestinal contamination that, when substantial, may mask some scattered tumor cells, and when injured and reactive, may mimic carcinoma. When these challenges are faced in a single case, a definitive diagnosis of malignancy may be impossible, but malignancy is probable. In these cases, where the degree of suspicion for malignancy is high enough to require therapeutic intervention, one may classify the lesion as suspicious for malignancy (SFM). This category has a very high positive predictive value for malignancy. The SFM diagnosis must be correlated with clinical symptoms and imaging characteristics. When a patient has a high clinical suspicion of pancreatic cancer and a pancreatic mass

on imaging studies, the diagnosis of suspicious most likely indicates the presence of cancer. AIP should be a clinical consideration as it is a well-known pitfall mimicker of PDAC clinically, radiologically and cytologically. The distinction between a positive diagnosis and an SFM diagnosis is based on both quantitative and qualitative criteria. Suspicious cases represent 5 to 12% of published cases, but most studies focus on pancreatic adenocarcinoma, so the number of cases that are considered as suspicious for pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors, acinar cell carcinomas or lymphomas is very difficult to establish. In this section, we will present the criteria for all of these tumors. In the context of endocrine or acinar cell tumors, the diagnosis of SFM is mainly used when, due to technical issues, one cannot definitively confirm the nature of the cells with ancillary techniques such as immunohistochemistry. Definition A specimen is SFM when some but an insufficient number of the typical features of a specific low grade malignant or high grade malignant neoplasm are present, mainly pancreatic adenocarcinoma. The cytological features raise a strong suspicion for malignancy, but the findings are qualitatively and/or quantitatively insufficient for a conclusive diagnosis. The morphologic features must be sufficiently atypical that malignancy is considered more probable than not. Criteria: Suspicious for adenocarcinoma Clusters of epithelial cells present with typical cytological abnormalities of well-differentiated adenocarcinoma, but some clusters do not display these abnormalities And/or the number of clusters presenting such abnormalities is too low (<6 clusters) Scant number of scattered high grade malignant cells are present Malignant cells masked by gastrointestinal contamination, inflammation, necrosis, or debris. Pancreatobiliary brushing with high-grade dysplasia Criteria: Suspicious for neuroendocrine tumor or solid-pseudopapillary neoplasm Scant to moderate cellularity monomorphic population of non-cohesive to small clusters of small- to medium-sized cells with indistinct neuroendocrine features to allow for a definitive diagnosis of PanNET, or insufficient cellular characteristics of an SPN such as branching papillary structures or hyaline cores tissue is not available for immunohistochemical studies to a specific diagnosis Criteria: Suspicious for acinar cell carcinoma

Moderate to high cellularity cells organized in loosely cohesive clusters and/or acini resembling normal pancreatic parenchyma monomorphic population of medium to large cells with abundant, granular eosinophilic cytoplasm mild anisonucleosis or three-dimensionality of cell clusters nucleus is round with finely granular chromatin nucleoli are either not prominent raising doubt about the acinar origin, or nucleoli are centrally located and of normal or slightly larger size and caliber similar to normal acini Large, cherry-red nucleoli in a few polygonal cells Criteria: Suspicious for Non-Hodgkin lymphoma lymphoma) monomorphous, small- to intermediate-sized lymphocytes (low-grade monomorphous or polymorphous, large cells (high grade lymphoma) lymphoglandular bodies in the background no tissue available to confirm clonality

Criteria: Suspicious for malignancy, not otherwise specified Numerous other malignancies may involve pancreatic parenchyma, including metastases and sarcomas. In these cases, insufficient malignant cells are present for conclusive diagnosis of malignancy and for classification of tumor type with ancillary testing. Cells are present in the specimen, but require further investigation. Category VI. Positive or Malignant Background Since 9 of 10 malignancies in the pancreas are conventional PDAC, the "positive" or "malignant" category is often related to this category. Low grade malignancies such as well-differentiated PanNET and SPN are included in the Neoplastic: Other category. Other high grade malignancies are also included here such as acinar cell carcinoma, PBL lymphoma and metastasis. Definition A group of neoplasms that unequivocally display malignant cytologic characteristics and include pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) and its variants, cholangiocarcinoma, acinar cell carcinoma, poorly-differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma (small cell or large cell NEC carcinoma), pancreatoblastoma, lymphomas, sarcomas and metastases to the pancreas. Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is a malignant invasive gland (duct) forming epithelial neoplasm typically composed of classic tubular glands, but, in variants, with other morphologically diverse epithelial morphologies. Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, or inltrating ductal adenocarcinoma, is the most common primary cancer of the pancreas which accounts for 8590% of all pancreatic malignancies. As in other organ-based cancers most patients are in their 60s and above; PDAC is quite uncommon in patients younger than 40 years of age. Pancreatic cancer is a one of the most lethal malignancies of human body with an extremely poor prognosis. It is considered the fourth leading cause of cancer death in the US and is estimated to cause 227, 000 deaths per year worldwide. The incidence and overall mortality caused by pancreatic cancer has been gradually rising. An estimated 20% of pancreatic cancers are caused by cigarette smoking . Other major risk factors include family history and familial syndromes, chronic pancreatitis, advancing age, male gender, diabetes mellitus, and obesity Typical presenting symptoms of pancreatic cancer include vague abdominal or mid-back pain, obstructive jaundice, weight loss and new-onset diabetes mellitus. Most if not all, early-stage pancreatic cancers are often clinically asymptomatic, and only become apparent after invasion of the tumor into the surrounding tissues or metastases to distant organs. A clinical/radiologic or pathologic diagnosis is usually rendered late when the cancer is unresectable. Overall survival is better for patients with locally advanced disease (median 915 months) than for those with metastatic disease (36 months). Cytologic Criteria Well-differentiated PDAC Variable cellularity with predominance of one cell type, i.e., ductal cells Cohesive small to medium-sized sheets of cells with smooth borders, and rarely single cells Three-dimensional fragments Moderate nuclear enlargement with high N/C ratios, cellular crowding and overlap Loss of nuclear polarity, often pale nuclei with chromatin clearing and/or clumping, nuclear membrane irregularity with clefts and notches Lack of prominent nucleoli Mild to moderate anisonucleosis (typically more than 4 to 1 in the same gland/duct) Rare mitoses Uncommon necrosis Moderately-differentiated PDAC Above features with addition of one or more of the following Larger cellular sheets/fragments with increased amount of single cells More extensive cellular pleomorphism Marked anisonucleosis and occasional prominent nucleoli

More crowded three-dimensional or syncytial tissue fragments

Poorly-differentiated PDAC Extreme pleomorphism, with almost total lack of glandular differentiation Larger loosely cohesive syncytial tissue fragments Significant populations of single large malignant cells High N/C ratio, nuclei with coarse dark chromatin and often macro nucleoli Occasional bizarre nuclei with triangular shapes and/or multinucleated cells Mitoses and karyorrhexis Prominent necrosis

Other Invasive Carcinomas of Pancreatobiliary Origin Cholangiocarcinoma The diagnostic criteria for invasive cholangiocarcinoma are the same as for PDAC on fine needle aspiration samples. Published diagnostic criteria for adenocarcinoma in a bile duct brushing specimen demonstrate variable predictive values Features associated with adenocarcinoma include: three dimensional cell clusters with marked nuclear crowding and loss of polarity, nuclear molding, papillary groups, cell-in-cell groups, cellular dyshesion, nuclear pleomorphism with nuclear membrane and chromatin irregularities, increased nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio, vacuolated or dense squamoid cytoplasm, atypical mitotic figures and background necrosis. , In the analysis by Renshaw et al , a consensus evaluation of loss of polarity had a sensitivity of 36% and a specificity of 97% for the diagnosis of adenocarcinoma. The sensitivity and specificity of a consensus diagnosis of bloody background was 15% and 88% respectively. Finally, the sensitivity and specificity for the combination of nuclear molding, chromatin clumping, increased nuclear cytoplasmic ratio, loss of honeycomb pattern, enlarged nuclei, bloody background and cell and cell arrangement was 36% and 95% respectively. An overall assessment for the presence of malignancy may be best in these samples. Major diagnostic pitfalls in the evaluation of bile duct brushings include obscuring of malignant epithelium by overlying benign epithelium , insufficient sampling, degeneration due to bile or duodenal contents, primary sclerosing cholangitis and atypical squamous metaplasia due to bile duct stones and stents. Correlation of the cytological findings with the clinical findings may help, as a biliary stricture is more likely to be malignant in older male patients who are symptomatic and do not have a history of stones Criteria Architectural

o Marked cellular dyshesion demonstrated by poorly cohesive groups and /or atypical single cells o Three dimensional cell clusters with marked nuclear crowding o Loss of polarity o Nuclear molding o Papillary groups o Syncytial groups o Cell-in-cell groups Nuclear o Large pleomorphic nuclei o Nuclear membrane irregularities, such as elongation, or blunting o Abnormal chromatin distribution o Atypical mitotic figures o Four fold or greater variation in nuclear size Cytoplasmic o vacuolated, squamous or dense cytoplasm o o Background Necrotic debris Bloody background with degenerated debris

Colloid carcinoma A carcinoma of ductal differentiation showing abundant extracellular mucin production, with at least 80% of the tumor on histology demonstrating large pools of extracellular mucin and cuboidal epithelial cells floating in the mucin. This uncommon variant accounts for 1-3% of PDAC and majority arise in association with intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN), intestinal type. Gender and age distribution is similar to PDAC; however, the prognosis appears to be significantly better. Cytologic Criteria Variable cellularity Abundant clean mucin Strips and small three-dimensional fragments of cuboidal epithelium with overt malignant features High N/C ratios, round nuclei, fine chromatin, prominent nucleoli A subpopulation of signet ring cells maybe present Typically no necrosis Inflammatory debris and calcifications may be present Medullary Carcinoma A carcinoma characterized by poor histologic differentiation, syncytial growth pattern, pushing borders, and an intense lymphoplasmacytic response. Medullary carcinoma is characterized by a special genetic profile with 69% of these tumors displaying wild-type k-ras genes and 22% of these tumors have microsatellite instability (MSI).

Cytologic Criteria Hypercellular Mostly large syncytial sheets, few single cells Monotonous cells with round nuclei, high N/C ratios, macronucleoli Variable amount of lymphocytes in the smear background Adenosquamous Carcinoma A variant of PDAC with glandular and squamous components ranging from extensive glandular differentiation with focal squamous differentiation to predominantly squamous differentiation. A rare subtype with relative frequency of 3-4% and relatively poorer prognosis compared to the conventional PDAC. Cytologic Criteria Cytomorphologic characteristics of well, moderately or poorly differentiated ductal adenocarcinoma Focal or confluent squamous differentiation keratinized squamous cells; singly, in tissue fragments and/or fragments of high grade non-keratinizing basaloid type cells Focal to extensive necrosis, often cystic background Undifferentiated Carcinoma with Osteoclast-like Giant Cells Often admixed with ordinary PDAC, this tumor is a distinctive type of sarcomatoid carcinoma with the striking and unique cytohistologic features characterized by a prominent component of reactive osteoclast-like giant cells in a background of spindle cells. Often seen in association with IPMN or MCN, these tumors may also arise with in-situ and invasive PDAC. Cytologic Criteria Hypercellular smears, composed predominantly of dispersed isolated single cells, or loosely cohesive cell groups Round to spindled, often pleomorphic and high-grade malignant cells Nuclei are hyperchromatic, often with prominent nucleoli A second population of multinucleated osteoclast-type giant cells (reactive histiocytes) scattered throughout the smear, often containing as many as 3050 nuclei An associated component of IPMN, MCN or PDAC may be present Often accompanied by hemorrhage and hemosiderin Anaplastic Carcinoma A rare variant of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma composed of large, undifferentiated, markedly pleomorphic cells. Also known as undifferentiated carcinoma

this tumor is rare with a relative frequency of 2-7% and may show small foci of poorlydifferentiated PDAC. Cytologic Criteria Usually cellular, predominantly single cells Extreme pleomorphism with marked anisonucleosis and bizarre, often multinucleated giant cells Hyperchromasia, macronucleoli No ductal or acinar differentiation Abundant abnormal mitoses Extensive necrosis Acinar Cell Carcinoma A rare malignant epithelial neoplasm with predominantly exocrine acinar differentiation. A rare primary malignancy, predominantly seen in older Caucasian men (mean age, 62 years). The presenting symptoms are usually nonspecific, and jaundice is often not present. Hypersecretory syndrome is present in only 16% of the patients. A significant proportion of the cases have neuroendocrine component or scattered neuroendocrine cells. Approximately 50% of the patients have metastatic disease at presentation, often restricted to the regional lymph nodes and liver. The prognosis appears to be significantly better than ordinary PDACs. Cytologic Criteria Usually hypercellular, mostly small to mid-sized cellular fragments and few single cells Prominent acinar formations without lobular arrangements (in welldifferentiated tumors that can be confused with rosettes of a PanNET), rare syncytia Uniform population of cells larger than ductal carcinoma, minimal pleomorphism Finely granular to denser cytoplasm, granularity is often basophilic Mildly increased N/C ratios, single round to oval nucleus which are eccentrically placed, coarse chromatin, single prominent nucleoli, focal anisonucleosis Significant anisonucleosis in high-grade tumors Numerous bare stripped off nuclei, rare intranuclear inclusions Rare necrosis Poorly-differentiated Neuroendocrine Carcinoma (Small Cell Carcinoma or Large Cell Neuroendocrine Carcinoma) A high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma, cytoarchitecturally and clinicopathologically exhibit features indistinguishable from its pulmonary (and extra pulmonary) counterparts. This accounts for less than 1% of all primary pancreatic cancers and 2-3% of PanNETs. Primary small cell carcinoma is extremely rare in pancreas and possibility of metastatic lung carcinoma should always be excluded first. Small cell carcinoma has an extremely poor prognosis and usually displays an extensive peripancreatic invasion. Chemotherapy remains the only mode of therapy.

Cytologic Criteria Hypercellular, with mostly single cells or loosely cohesive cell groups Barely discernible cell cytoplasm with mostly bare round to oval nuclei Nuclei display hyperchromasia, finely granular chromatin, lack of nucleoli, nuclear molding and crush artifact Abundant mitoses and karyorrhexis and often necrosis Pancreatoblastoma A rare neoplasm, primarily of childhood, characterized by acinar differentiation, endocrine differentiation and distinctive squamoid nests. Also known as infantile pancreatic carcinoma, this is an extremely rare pancreatic tumor in childhood, comprising 0.5% of pancreatic non-endocrine tumors with rare occurrence in adults. Pancreatoblastoma tend to be less aggressive in infants and children compared to adults. The cancer has been associated with alterations in the Wnt signaling pathway and chromosome 11p loss of heterozygosity (LOH), Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome and familial adenomatous polyposis. Alpha-fetoprotein may be elevated in up to 68% of patients with pancreatoblastoma. Cytologic Criteria Hypercellular smears Tissue fragments of varying sizes with solid sheets, three dimensional loosely cohesive epithelial groups, abundant stromal tissue Primitive spindled mesenchymal tissue (rare focal cartilage formation) Epithelial component with mostly acinar formations, nests and organoid patterns Epithelial cells appear cuboidal with central nuclei, indistinct nucleoli, and clear cytoplasm Spindle-shaped, elongated and triangular-shaped epithelial cells Cells in the acinar formations had a slightly elongated columnar shape with more abundant delicate cytoplasm and basally-placed nuclei and prominent Focally, the large epithelial cells formed swirling eddies consistent with squamoid corpuscles (mostly cell block) Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Hematopoietic malignancies in the pancreas are rare and usually involve the pancreas secondarily. Pancreatic lymphomas are most commonly non-Hodgkins lymphoma that can clinically mimic pancreatic adenocarcinoma. One of the advantages to FNA evaluation is that pre-operative diagnosis of lymphoma can preclude unnecessary surgery. Primary pancreatic lymphomas are most commonly large B-cell lymphomas. While the cytomorphological features may suggest lymphoid differentiation, there may be overlapping features with other neoplasms that produce a solid cellular smear pattern. Ancillary tests

such as flow cytometry and immunohistochemistry are typically necessary for diagnosis and especially for subclassification. Metastatic tumors Secondary neoplasms involving the pancreas are rare, and pancreatic involvement as the sole site of metastasis is even more uncommon. The common neoplasms that metastasize to the pancreas include melanoma, and carcinomas from the lung, colorectum and breast. Direct extension from cancer of the stomach, duodenum, gallbladder, liver and retroperitoneum may also occur. Renal cell carcinoma is notorious for giving rise to a late solitary metastasis, even decades following nephrectomy. Renal cell carcinoma is also the most likely malignancy to metastasize to the pancreas and mimic a primary neoplasm. The cytological findings of metastatic renal cell carcinoma are similar to those seen in the kidney with bland polygonal cells, round slightly eccentric nuclei, prominent nucleoli and vacuolated cytoplasm. Distinction from clear cell or lipid rich neuroendocrine tumor is warranted as the morphology of these two neoplasms may be indistinguishable.

References 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. Tanaka M, Chari S, Adsay V, et al. International consensus guidelines for management of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms and mucinous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. Pancreatology 2006; 6(1-2): 17-32. Tanaka M, Fernandez-del Castillo C, Adsay V, et al. International consensus guidelines 2012 for the management of IPMN and MCN of the pancreas. Pancreatology in press. Mallery JS, Centeno BA, Hahn P, et al. Pancreatic tissue sampling guided by EUS, CT/US, and surgery: a comparison of sensitivity and specificity. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy 2002; 56(2): 218-224. Chang KJ. Endoscopic Ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration in the diagnosis and staging of pancreatic tumors. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Clinics of North America 1995; 5(4): 723-734. Erickson RA, Sayage-Rabie L, and Avots-Avotins A. Clinical utility of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration. Acta Cytologica 1997; 41(6): 1647-1653. Faigel DO, Ginsberg GG, Bentz JS, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided real-time fine-needle aspiration biopsy of the pancreas in cancer patients with pancreatic lesions. Journal of Clinical Oncology 1997; 15(4): 1439-1443. Bhutani MS, Hawes RH, Baron PL, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound guided fine needle aspiration of malignant pancreatic. Endoscopy 1997; 29(9): 854-8. Bentz JS, Kochman ML, Faigel DO, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided real-time fine-needle aspiration: clinicopathologic features of 60 patients. Diagnostic Cytopathology 1998; 18(2): 98-109. Suits J, Frazee R, and Erickson RA. Endoscopic ultrasound and fine needle aspiration for the evaluation of pancreatic masses. Arch Surg 1999; 134(6): 639-42; discussion 642-3. Williams DB, Sahai AV, Aabakken L, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound guided fine needle aspiration biopsy: A large single centre experience. Gut 1999; 44: 720-726. Sahai AV, Schembre D, Stevens PD, et al. A multicenter U.S. experience with EUSguided fine-needle aspiration using the Olympus GF-UM30P echoendoscope: safety and effectiveness. Gastrointest Endosc 1999; 50(6): 792-6. Erickson RA, Sayage-Rabie L, and Beissner RS. Factors predicting the number of EUS-guided fine-needle passes for diagnosis of pancreatic malignancies. Gastrointest Endosc 2000; 51(2): 184-90. Ylagan LR, Edmundowicz S, Kasal K, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound guided fineneedle aspiration cytology of pancreatic carcinoma: a 3-year experience and review of the literature. Cancer 2002; 96(6): 362-9. Shin HJ, Lahoti S, and Sneige N. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration in 179 cases: the M. D. Anderson Cancer Center experience. Cancer 2002; 96(3): 174-80. Eloubeidi MA, Jhala D, Chhieng DC, et al. Yield of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy in patients with suspected pancreatic carcinoma. Cancer 2003; 99(5): 285-92.

16. 17. 18.

19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. 26. 27. 28. 29. 30. 31.

Frossard JL, Amouyal P, Amouyal G, et al. Performance of endosonography-guided fine needle aspiration and biopsy in the diagnosis of pancreatic cystic lesions. The American Journal of Gastroenterology 2003; 98(7): 1516-1524. Eloubeidi MA and Tamhane A. EUS-guided FNA of solid pancreatic masses: a learning curve with 300 consecutive procedures. Gastrointest Endosc 2005; 61(6): 700-8. Eloubeidi MA, Varadarajulu S, Desai S, et al. A prospective evaluation of an algorithm incorporating routine preoperative endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration in suspected pancreatic cancer. J Gastrointest Surg 2007; 11(7): 813-9. Agrawal D, Moparty B, and Brugge WR. EUS-FNA Cytology of pancreatic masses: performance characteristics improve with time (nine years) and experience (712 patients. Gastrointest Endosc 2007; 65: AB306. Jhala NC, Jhala D, Eltoum I, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration biopsy: A powerful tool to obtain samples from small lesions. Cancer Cytopathology 2004; 102(4): 239-246. Klapman JB, Logrono r, Dye CE, et al. Clinical impact of on-site cytopathology interpretation on endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration. Am J Gastroenterol 2003; 98(6): 1289-94. Brandwein S, Farrell J, Centeno B, et al. Detection and tumor staging of malignancy in cystic, intraductal, and solid tumors of the pancreas by EUS. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy 2001; 53(7): 722-727. Logrono R, Kurtycz DF, Molina CP, et al. Analysis of false-negative diagnoses on endoscopic brush cytology of biliary and pancreatic duct strictures: the experience at 2 university hospitals. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2000; 124(3): 387-92. Elek G, Gyokeres T, Schafer E, et al. Early diagnosis of pancreatobiliary duct malignancies by brush cytology and biopsy. Pathol Oncol Res 2005; 11(3): 145-55. Foutch PG, Kerr DM, Harlan JR, et al. A prospective, controlled analysis of endoscopic cytotechniques for diagnosis of malignant biliary strictures. Am J Gastroenterol 1991; 86(5): 577-80. Rabinovitz M, Zajko AB, Hassanein T, et al. Diagnostic value of brush cytology in the diagnosis of bile duct carcinoma: a study in 65 patients with bile duct strictures. Hepatology 1990; 12(4 Pt 1): 747-52. Kocjan G and Smith AN. Bile duct brushings cytology: potential pitfalls in diagnosis. Diagn Cytopathol 1997; 16(4): 358-63. Volmar KE, Vollmer RT, Routbort MJ, et al. Pancreatic and bile duct brushing cytology in 1000 cases: review of findings and comparison of preparation methods. Cancer 2006; 108(4): 231-8. Glasbrenner B, Ardan M, Boeck W, et al. Prospective evaluation of brush cytology of biliary strictures during endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Endoscopy 1999; 31(9): 712-7. Stewart CJ, Mills PR, Carter R, et al. Brush cytology in the assessment of pancreatico-biliary strictures: a review of 406 cases. J Clin Pathol 2001; 54(6): 44955. Kurzawinski T, Deery A, and Davidson BR. Diagnostic value of cytology for biliary stricture. Br J Surg 1993; 80(4): 414-21.

32. 33. 34. 35. 36. 37. 38. 39. 40. 41. 42. 43. 44. 45. 46. 47.

Kurzawinski TR, Deery A, Dooley JS, et al. A prospective study of biliary cytology in 100 patients with bile duct strictures. Hepatology 1993; 18(6): 1399-403. Bardales RH, Stanley MW, Simpson DD, et al. Diagnostic value of brush cytology in the diagnosis of duodenal, biliary, and ampullary neoplasms. Am J Clin Pathol 1998; 109(5): 540-8. Siddiqui MT, Gokaslan ST, Saboorian MH, et al. Comparison of ThinPrep and conventional smears in detecting carcinoma in bile duct brushings. Cancer 2003; 99(4): 205-10. Oh HC, Kim MH, Hwang CY, et al. Cystic lesions of the pancreas: challenging issues in clinical practice. Am J Gastroenterol 2008; 103(1): 229-39; quiz 228, 240. Brugge WR, Lewandrowski K, Lee-Lewandrowski E, et al. Diagnosis of pancreatic cystic neoplasms: a report of the cooperative pancreatic cyst study. Gastroenterology 2004; 126(5): 1330-6. Belsley NA, Pitman MB, Lauwers GY, et al. Serous cystadenoma of the pancreas: limitations and pitfalls of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy. Cancer 2008; 114(2): 102-10. Payne M, Staerkel G, and Gong Y. Indeterminate diagnosis in fine-needle aspiration of the pancreas: reasons and clinical implications. Diagn Cytopathol 2009; 37(1): 219. Jarboe EA and Layfield LJ. Cytologic features of pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia and pancreatitis: potential pitfalls in the diagnosis of pancreatic ductal carcinoma. Diagn Cytopathol 2011; 39(8): 575-81. Nagle J, Wilbur DC, and Pitman MD. The cytomorphology of gastric and duodenal epithelium and reactivity to B72.3: A baseline for comparison to pancreatic neoplasms aspirated by EUS-FNAB. Diagn Cytopathol 2005; 33: 381-6. Nawgiri RS, Nagle JA, Wilbur DC, et al. Cytomorphology and B72.3 labeling of benign and malignant ductal epithelium in pancreatic lesions compared to gastrointestinal epithelium. Diagn Cytopathol 2007; 35(5): 300-5. Zen Y, Adsay NV, Bardadin K, et al. Biliary intraepithelial neoplasia: an international interobserver agreement study and proposal for diagnostic criteria. Mod Pathol 2007; 20(6): 701-9. Lee JG, Leung JW, Baillie J, et al. Benign, dysplastic, or malignant-making sense of endoscopic bile duct brush cytology: results in 149 consecutive patients. American Journal of Gastroenterology 1995; 90(5): 722-726. van der Waaij LA, van Dullemen HM, and Porte RJ. Cyst fluid analysis in the differential diagnosis of pancreatic cystic lesions: a pooled analysis. Gastrointest Endosc 2005; 62(3): 383-9. Cizginer S, Turner B, Bilge AR, et al. Cyst Fluid Carcinoembryonic Antigen Is an Accurate Diagnostic Marker of Pancreatic Mucinous Cysts. Pancreas 2011. Hruban RH, Bolfetta P, Hiraoka N, et al. Tumours of the pancreas, in WHO Classification of Tumours of the Digestive System, F.T. Bosman, et al., Editors. 2010, IARC: Lyon. 279. Crippa S, Fernandez-Del Castillo C, Salvia R, et al. Mucin-producing neoplasms of the pancreas: an analysis of distinguishing clinical and epidemiologic characteristics. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010; 8(2): 213-9.

48. 49. 50. 51. 52. 53. 54. 55.

56. 57. 58. 59. 60. 61. 62. 63.

Crippa S, Salvia R, Warshaw AL, et al. Mucinous cystic neoplasm of the pancreas is not an aggressive entity: lessons from 163 resected patients. Ann Surg 2008; 247(4): 571-9. Hruban RH, Pitman MB, and Klimstra DS. Tumors of the Pancreas. Atlas of Tumor Pathology, 4th series, fascicle 6. 2007, Washington, D.C.: American Registry of Pathology; Armed Forces Institutes of Pathology. Pitman MB and Deshpande V. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration cytology of the pancreas: a morphological and multimodal approach to the diagnosis of solid and cystic mass lesions. Cytopathology 2007; 18(6): 331-47. Pitman MB, Genevay M, Yaeger K, et al. High-grade atypical epithelial cells in pancreatic mucinous cysts are a more accurate predictor of malignancy than "positive" cytology. Cancer Cytopathol 2010; 118: 434-40. Pitman MB, Michaels PJ, Deshpande V, et al. Cytological and cyst fluid analysis of small (< 3 cm) branch duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms adds value to patient management decisions. Pancreatology 2008; 8: 277-284. Adsay NV. Cystic neoplasia of the pancreas: pathology and biology. J Gastrointest Surg 2008; 12(3): 401-4. Adsay NV, Longnecker DS, and Klimstra DS. Pancreatic tumors with cystic dilatation of the ducts: Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms and intraductal oncocytic papillary neoplasms. Semin Diagn Pathol 2000; 17: 16-31. Adsay NV, Merati K, Basturk O, et al. Pathologically and biologically distinct types of epithelium in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms: delineation of an "intestinal" pathway of carcinogenesis in the pancreas. Am J Surg Pathol 2004; 28(7): 839-48. Hruban RH, Takaori K, Klimstra DS, et al. An illustrated consensus on the classification of pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia and intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms. American Journal of Surgical Pathology 2004; 28(8): 977-87. Adsay NV, Pierson C, Sarkar F, et al. Colloid (mucinous noncystic) carcinoma of the pancreas. American Journal of Surgical Pathology 2001; 25(1): 26-42. Mino-Kenudson M, Fernandez-Del Castillo C, Baba Y, et al. Prognosis of invasive intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm depends on histological and precursor epithelial subtypes. Gut 2011; 60(12): 1712-20. Moparty B, Pitman MB, and Brugge WR. Pancreatic cyst fluid amylase is not a marker to differentiate IPMN from MCN. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy 2007; 65(5): AB303. Ryu JK, Woo SM, Hwang JH, et al. Cyst fluid analysis for the differential diagnosis of pancreatic cysts. Diagn Cytopathol 2004; 31(2): 100-5. O'Toole D, Palazzo L, Hammel P, et al. Macrocystic pancreatic cystadenoma: The role of EUS and cyst fluid analysis in distinguishing mucinous and serous lesions. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy 2004; 59(7): 823-9. Khalid A, Zahid M, Finkelstein SD, et al. Pancreatic cyst fluid DNA analysis in evaluating pancreatic cysts: a report of the PANDA study. Gastrointest Endosc 2009; 69(6): 1095-102. Shen J, Brugge WR, Dimaio CJ, et al. Molecular analysis of pancreatic cyst fluid: a comparative analysis with current practice of diagnosis. Cancer Cytopathol 2009; 117(3): 217-27.

64. 65. 66. 67. 68. 69. 70. 71. 72. 73. 74. 75. 76. 77. 78. 79.

80.

Wu J, Matthaei H, Maitra A, et al. Recurrent GNAS mutations define an unexpected pathway for pancreatic cyst development. Sci Transl Med 2011; 3(92): 92ra66. Lau SK, Lewandrowski KB, Brugge WR, et al. Diagnostic significance of mucin in fine needle aspiration samples of pancreatic cysts. Modern Pathology 2000; 13(3): 48A. Layfield LJ and Cramer H. Fine-needle aspiration cytology of intraductal papillarymucinous tumors: A retrospective analysis. Diagnostic Cytopathology 2005; 32(1): 16-20. Kloek JJ, van der Gaag NA, Erdogan D, et al. A comparative study of intraductal papillary neoplasia of the biliary tract and pancreas. Hum Pathol 2011; 42(6): 82432. Barton JG, Barrett DA, Maricevich MA, et al. Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the biliary tract: a real disease? HPB (Oxford) 2009; 11(8): 684-91. Ando N, Goto H, Niwa Y, et al. The diagnosis of GI stromal tumors with EUSguided fine needle aspiration with immunohistochemical analysis. Gastrointest Endosc 2002; 55(1): 37-43. Reith JD, Goldblum JR, Lyles RH, et al. Extragastrointestinal (soft tissue) stromal tumors: an analysis of 48 cases with emphasis on histologic predictors of outcome. Modern Pathology 2000; 13(5): 577-585. Willmore-Payne C, Layfield LJ, and Holden JA. c-KIT mutation analysis for diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors in fine needle aspiration specimens. Cancer 2005; 105(3): 165-70. Lin F and Staerkel GA. Cytologic criteria for well differentiated adenocarcinoma of the pancreas in fine-needle aspiration biopsy specimens. Cancer 2003; 99(1): 44-50. Robins DB, Katz RL, Evans DB, et al. Fine needle aspiration of the pancreas. In quest of accuracy. Acta Cytologica 1995; 39(1): 1-10. Cohen MB, Wittchow RJ, Johlin FC, et al. Brush cytology of the extrahepatic biliary tract: comparison of cytologic features of adenocarcinoma and benign biliary strictures. Mod Pathol 1995; 8: 498-502. Nakajima T, Tajima Y, Sugano I, et al. Multivariate statistical analysis of bile cytology. Acta Cytol 1994; 38(1): 51-5. Renshaw AA, Madge R, Jiroutek M, et al. Bile duct brushing cytology. Statistical analysis of proposed diagnostic criteria. Am J Clin Pathol 1998; 110: 635-640. Layfield LJ and Cramer H. Primary sclerosing cholangitis as a cause of false positive bile duct brushing cytology: report of two cases. Diagn Cytopathol 2005; 32(2): 11924. Adsay NV, Pierson C, Sarkar F, et al. Colloid (mucinous noncystic) carcinoma of the pancreas. Am J Surg Pathol 2001; 25(1): 26-42. Nakata K, Ohuchida K, Aishima S, et al. Invasive carcinoma derived from intestinaltype intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm is associated with minimal invasion, colloid carcinoma, and less invasive behavior, leading to a better prognosis. Pancreas 2011; 40(4): 581-7. Yopp AC, Katabi N, Janakos M, et al. Invasive carcinoma arising in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas: a matched control study with conventional pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg 2011; 253(5): 968-74.

81. 82. 83. 84. 85. 86. 87. 88. 89. 90. 91.