Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Chapter 57

Uploaded by

minchanmonOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Chapter 57

Uploaded by

minchanmonCopyright:

Available Formats

1

CHAPTER 5

RECOGNITION OF STATES AND GOVERNMENTS

Contents

Pages

5.1

Theories of Recognition

5.2

Recognition of Government

5.3

De facto and de jure recognition

14

5.4

Legal Consequence of Recognition

20

Recognition of States and Governments

5.1 Theories of Recognition

There are two theories of recognition, namely:

(a) the constitutive theory, and

(b) the declaratory or evidentiary theory.

()

()

Constitutive Theory

According to the constitutive theory, without recognition a

State does not exist, and only recognition constitutes a State as an

international person and gives it clear-cut rights and responsibilities.

Supporter of the constitutive theory are Oppenheim, Lauterpacht, Hans

Kelsen, ect. Oppenheim writes that "through recognition only and

exclusively a State becomes an international person and a subject of

international law, and that recognition is constitutive of the rights and

2

duties pertaining to Statehood".

Oppenheim,

Lauterpacht, Hans Kelsen

Oppenheim

Many jurists do not agree with this theory. That is because there are

serious difficulties in it. For instance, the status of a State recognized by

States A but not recognized by State B, and therefore apparently both an

international person and not an international person at the same time,

would be a legal curiosity. Perhaps a more substantial difficulty is that

unrecognized State has neither rights nor duties at international law. For

example, an intervention, otherwise illegal would not have been illegal in

2

. Oppenheim, International Law, pp. 125-127.

unrecognized State. Moreover, if the unrecognized State had been

involved in war, she would have been under no legal obligation to respect

the

rights

of neutrals. Non-recognition may certainly make

the

enformcement of rights and duties more difficult. The practice of States

does not support the view that they have no legal existence before

recognition.

'' ''

''''

J.L. Briery,The Law of Nation, pp.138-139.

A new State, being a subject of international law from its very

inception, enters into many kinds of relations with existing States even

prior to its recognition. The case of the Soviet Union is particularly

2

instructive in this respect. Another striking example is the problem of non

recognition of the People's Republic of China by the United States of

America.

Declaratory Theory

2

Yevgeryev, in 'International Law', Moscoe, pp. 122-123.

According to the declaratory theory, Statehood exists prior to

recognition

and

the

act

of

recognition

is

merely

formal

acknowledgement of an already established fact.

The Montevideo Convention: 1933, is in accord with this theory. It

prescribes as follows:

"The political existence of the State is independent of

recognition by the other States. Even before recognition the State has the

right to defend its integrity and independence, to legislate upon its

interests, and to define the jurisdiction and competence of its courts".

Article 3 of the Montevideo Convention (the Inter American Convention on Rights and Duties of State,

December 26,1933)

The exponents of the declaratory theory are Hall, Fischer Williams,

J.L. Briery, Richard N. Swift, etc.

Hall, Fischer Williams, J.L. Briery, Richard N. Swift

According to Professor Brierly "the better view is that the granting

of recognition to a new State is not a constitutive but a declaratory act. It

does not bring into existence a State which did not exist before. A State

may exist without being recognized, and if it does exist in fact, then,

whether or not it has been formally recognized by other States, it has a

right to be treated by them as a State.

J.L, Birely, The Law of Nations, p. 139.

Richard N.Swift, a well known American Professor, is of the opinion

that "the declaratory theory, by contrast with the constitutive" corresponds

more closely to reality".

Comparatively speaking, the constitutive theory represents a

minority view among writers.

5.2 Recognition of Government

Logically the recognition of a new state automatically involves

recognition of the government of the State. However, although recognition

2

3

.

.

Richard N. Swift International Law: Current and Classic, 1968, p. 61.

Von Glahn, Law Among Nations, p. 91.f.n; H.W. Briggs, "Recognition of States:

Some reflections on Doctrine and Practice", 43 A.J.I.L (1949), PP, 113-121.

of government and State may be closely related, they are not necessarily

identical. The question of recognition of a government apart from the

question of recognition a new State arises in certain circumstances.

In fact, the granting or refusing of the recognition of a government

has nothing to do with recognition of the State itself. If a foreign State

refuses to recognize a new government of an old State the latter does not

thereby lose its recognition as an international person.

( )

In practice, when there is a change of government in a normal and

constitutional manner, recognition is granted as a matter of fact. For

10

example, in the case of the accession of a new Head of a State, other States

usually recognize the new Head by some formal act such as a message of

4

congratulation.

When, however, the new government comes into power not in a

constitutional manner but after a coup' etat, a revolution (which need not

involve bloodshed), the difficulty arises. Other State need to decide on the

question whether the new government can be properly regarded as

representing the State in question. In arriving at the decision they exercise

a discretion.

Oppenheim, op, cit, p. 129.

11

The decision nevertheless has to arrive at with regard to the

1

particular facts of each case and on the basis of certain tests. There seems

to be two tests to be applied in such cases.

(a)

Objective test

The objective test is regarded by some jurists as the "Principle

of Effectiveness".

According to Oppenheim, a government which enjoys the habitual

obedience of the bulk of the population with a reasonable expectancy of

permanence, can be said to represent the State in question and as such to

1

2

.

.

B.Sen, op. cit, p. 422.

Ibid.

12

be entitled to recognition. The eminent jurist also maintains that the

preponderant practice of States in the matter of recognition of government

is based on the principle of effectiveness thus conceived.

The principle of effectiveness is the traditional theory and is

supported by many jurists.

Oppenheim, op. cit, p. 131.

13

(b)

Subjective test

The second half of the nineteenth century witnessed the

emergence of a second test, applied by some States. This test is whether

the new government has willingness to carry out the international legal

obligations of its State. This is called the subjective test.

The United

States applied this test in the case of the Soviet (Russia) when she emerged

as a result of the revolution of 1917. However, Oppenheim is of the

opinion that this test cannot be regarded as satisfactory.

4

5

.

.

Von Glahn, Law Among Nations, p.99.

Oppenheim, op. cit, p.133.

14

5.3 De facto and de jure recognition

There are two modes of recognition under international law

recognition de facto and de jure. This division, although effective to this

day, is relative, since there are no international treaty rules regarding this

matter.

States, in order to safeguard their position against granting of

premature recognition, have often resorted according to the practice of

recognition de facto before recognizing a State government de jure.

15

De facto recognition of a State or government takes place when, in

the view of the recognizing State, the new authority, although actually

independent and having effective power in the territory under its control,

has not acquired sufficient stability or does not as yet offer prospects of

complying with other requirements of recognition such as willingness or

ability to fulfil international obligation.

( )

( )

Recognition de facto is, in essence, provisional and liable to be

withdrawn if the absent requirements of recognition fall to materialize.

3

4

.

.

Oppenheim, International Law, Vol. I, p.135.

Ibid, p.136.

16

Consequently, recognition, de facto is incomplete. It is a transitional state

leading to de jure recognition this may follow much later.

As a rule, in the case of recognition de facto, there is not yet formal

exchange of diplomatic representatives.

De jure recognition implies that the recognized State or government

fulfils the test laid down by international law for effective participation in

international community.

( )

.

.

2

.

1

Yevgenyev, in International Law, Moscow, p.118.

Lauterpacht, Recognition in International Law, p.338.

Tandon, Public International Law, p.154.

17

According to British practice three conditions are required as a

precedence to the grant of de jure recognition, namely:

(a) a reasonable assurance of stability and permanence.

(b) the government commands the general support of the

population; and

(c) it is able and willing to fulfil its international obligation.

()

()

()

()

Recognition de jure is full recognition, leading to the establishment

of extensive relations of many kinds. It is more stable in character than is

Smith, Great Britain and The Law of Nations, Vol: I, p.79.

18

so in the case of de facto recognition. The most important results of de jure

recognition include.

(a) the establishment of full diplomatic and consular relations

with the State recognized.

(b)the participation of the State recognized in international

congress and conferences of a general character, and not only

those affecting its own interests;

(c)recognition and respect from the recognizing States for the

laws and decisions of the administrative and judicial organs of

the State recognized.

()

Yevgenyev, in International Law, Moscow, pp. 118-119.

19

()

()

Recognition de jure is therefore the more complete form. It

contributes to the development of relations between states.

From the point of view of legal effects there is hardly any difference

between de jure and de facto recognition.

The legislative and other

internal measures of the authority recognized de facto are, before the

courts of the recognizing States, treated on the same footing as those of a

1

State or government recognized de jure. Similarly, a Sates or government

5

1

.

.

Lauterpacht. Recognition in International Law, p. 343.

Oppenheim, op. cit, p. 136.

Luther V. Sagor (1921) 3K. B. 532.

20

recognized de facto enjoys jurisdictional immunity in the courts of the

recognizing State.

5.4 Legal Consequence of Recognition

Professor Oppenheim sums up the consequences which flow from

the recognition of a new government or State in these words:

Professor Oppenhein ()

(a) It thereby acquires the capacity to enter into diplomatic

relations with other States and to make treaties with them;

The Garara (1919), p. 95.

The Arantzazu Mendi, (1939), A. C. 216.

21

()

(b) Within limitations, former treaty (if any) concluded

between the two States, assuming it to be an old State and

not a newly-born State, are automatically reviewed and

come into force;

()

(c) It thereby acquires the right of suing in the courts of law of

the recognizing States;

()

( )

(d) It thereby acquires for itself and its property immunity from

the jurisdiction of the courts of law of the recognizing

State;

22

()

( )

(e) It also becomes entitled to demand and receive possession

of property situated within the jurisdiction of a recognizing

State

which

formerly

belonged

to

the

preceding

government at the time of its suppression; and

()

(f) Recognition being retroactive

and dating back to the

moment at which the newly recognized government

established itself in power, its effect is to preclude the

courts of the recognizing State from questioning the

legality or validity of such legislative and executive acts, of

past and future, of that government as are not contrary to

international law.

()

( )

1

Oppenheim, I.L. Vol: I, pp. 137-139.

23

( )

24

KEY TERMS

Constitutive theory

Declaratory (or) Evidentiary theory

Recognition

Integrity

Accession

Objective test

Subjective test

De facto recognition

De jure recognition

Consequences

Immunity

Legality

25

Validity

Limitations

Competence

Montevideo Convention

26

EXERCISE QUESTIONS

Assignment Questions

1. Explain theories of recognition and say which one corresponds more

closely to reality?

2. Briefly discuss the problem of recognition of governments.

3. What do you understand by de jure and de facto recognition?

4. Elaborate the legal consequences of recognition.

Short Questions

1. What kinds of recognition of theories are there? Write short notes

about the

recognition of theories.

2. Write short notes on the followings:

(a) Objective test

(b) Subjective test

3. Explain about the Montevideo Convention 1933 under the Declaratory

Theory.

You might also like

- Notice To Persons Acting Under Color of LawDocument21 pagesNotice To Persons Acting Under Color of Lawjpes100% (7)

- Identification Credentials: Mandatory or Voluntary?From EverandIdentification Credentials: Mandatory or Voluntary?Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Essential Legal Knowledge ALL PEOPLE SHOULD KNOW United States Secrets Why You Should Not Be A Citizen Person or PeopleDocument4 pagesEssential Legal Knowledge ALL PEOPLE SHOULD KNOW United States Secrets Why You Should Not Be A Citizen Person or PeopleClaudiaNo ratings yet

- The Story of Burt Handout #2 by Freeman Burt in ColoradoDocument16 pagesThe Story of Burt Handout #2 by Freeman Burt in ColoradoVen Geancia100% (2)

- State Vs Fed CitizenDocument11 pagesState Vs Fed CitizenKeesha Atkins100% (1)

- You Are Not A Party To It! Enslaved by Consent!Document118 pagesYou Are Not A Party To It! Enslaved by Consent!rooseveltkyle100% (4)

- You Are Not A Party To ItDocument125 pagesYou Are Not A Party To ItMarco De Moor Bey100% (3)

- 14th Amendment Flow ChartDocument6 pages14th Amendment Flow Chartdmsurveysspam100% (7)

- On Viruses and Common LawDocument5 pagesOn Viruses and Common LawLionNo ratings yet

- What Is The Legal Definition of A PersonDocument78 pagesWhat Is The Legal Definition of A PersonZoSo Zeppelin100% (3)

- Who Are YouDocument10 pagesWho Are Yousil_shakir100% (1)

- An Appeal To The People of America-2Document10 pagesAn Appeal To The People of America-2Sam Fisher100% (1)

- African Americans LESSON 1Document8 pagesAfrican Americans LESSON 1Netjer Lexx TV100% (2)

- The U.S. Constitution and MoneyDocument16 pagesThe U.S. Constitution and Moneymichael s rozeff100% (1)

- 26 State Foreign Post PDFDocument32 pages26 State Foreign Post PDFjoe100% (2)

- Proper ProseDocument71 pagesProper ProseSHAKIM LESLIE100% (1)

- Importance of State RecognitionDocument19 pagesImportance of State RecognitionAishwarya SinghalNo ratings yet

- Public International Law Exam NotesDocument80 pagesPublic International Law Exam NotesHaydenDavid95% (39)

- Debunking The Notion of A Living Constitution by Yurii RamosDocument31 pagesDebunking The Notion of A Living Constitution by Yurii RamosJayson Cabello100% (1)

- Behind the Bill of Rights: Timeless Principles that Make It TickFrom EverandBehind the Bill of Rights: Timeless Principles that Make It TickNo ratings yet

- 05-29-2011 Rod Class Navy LetterDocument7 pages05-29-2011 Rod Class Navy Letterrodclassteam100% (1)

- PILDocument4 pagesPILJoselle ReyesNo ratings yet

- Statehood and Its Relevance in Realm of International LawDocument8 pagesStatehood and Its Relevance in Realm of International LawUjjwal MishraNo ratings yet

- Bill of Rights Notes CompleteDocument5 pagesBill of Rights Notes Completeapi-328061525100% (1)

- PIL Lecture 1Document9 pagesPIL Lecture 1Yohanna J K GarcesNo ratings yet

- Recognition of States Under International LawDocument6 pagesRecognition of States Under International LawBilal akbar100% (1)

- Law of Persons: Legal Subjects and Legal ObjectsDocument4 pagesLaw of Persons: Legal Subjects and Legal ObjectsKelli FinleyNo ratings yet

- Glossary of Terms Commonly Used in Refugee Resettlement ProcessingDocument34 pagesGlossary of Terms Commonly Used in Refugee Resettlement ProcessingTamber HiltonNo ratings yet

- International LawDocument7 pagesInternational LawSumit TomarNo ratings yet

- Pre-Reading: Legal System in The USADocument6 pagesPre-Reading: Legal System in The USAMonicaMartirosyanNo ratings yet

- The Idea A Legitimate State: DavidDocument43 pagesThe Idea A Legitimate State: Davidasm_samNo ratings yet

- Constitution Day BookmarksDocument2 pagesConstitution Day BookmarksAbby SpearsNo ratings yet

- Proposal You Can Paraphrase FromDocument7 pagesProposal You Can Paraphrase Fromprachi singlaNo ratings yet

- States and International OrganizationDocument9 pagesStates and International OrganizationNisha SinghNo ratings yet

- States and International OrganizationDocument9 pagesStates and International OrganizationNisha SinghNo ratings yet

- History, Concept of Human Rights and Human Rights Situation in The CountryDocument11 pagesHistory, Concept of Human Rights and Human Rights Situation in The CountryKyle CastilloNo ratings yet

- Summary Order: United States Court of Appeals For The Second CircuitDocument8 pagesSummary Order: United States Court of Appeals For The Second CircuitLatisha WalkerNo ratings yet

- Thesis On Habeas Corpus and The War On TerrorDocument4 pagesThesis On Habeas Corpus and The War On Terrorgjbyse71100% (1)

- RelationsDocument107 pagesRelationsAian AlicnaNo ratings yet

- 2 D Yfs AdministrationsDocument3 pages2 D Yfs AdministrationseNo ratings yet

- Elements of International and Eu Law - Lecture 2 - 22/09/2020Document9 pagesElements of International and Eu Law - Lecture 2 - 22/09/2020Olena KhoziainovaNo ratings yet

- Full Download Criminal Law and Procedure 7th Edition Hall Solutions ManualDocument21 pagesFull Download Criminal Law and Procedure 7th Edition Hall Solutions Manualthomaswg1san100% (41)

- Legal Literacy ProjectDocument12 pagesLegal Literacy ProjectTanvi ONo ratings yet

- About The UsaDocument45 pagesAbout The UsaTrang NguyenNo ratings yet

- ExtraditionDocument22 pagesExtraditionRachit MunjalNo ratings yet

- PIL AssignmentDocument4 pagesPIL AssignmentAnsh SaliNo ratings yet

- Adminpujojs,+Cap +3Document30 pagesAdminpujojs,+Cap +3charuNo ratings yet

- Constitutionalism-A Perspective: Varun Chhachhar & Arun Singh NegiDocument13 pagesConstitutionalism-A Perspective: Varun Chhachhar & Arun Singh Neginawab112100% (3)

- Create-A-Constitution Directions and RubricDocument4 pagesCreate-A-Constitution Directions and Rubricapi-230389548100% (1)

- Simulation BriefDocument20 pagesSimulation Briefapi-235733472No ratings yet

- International LawDocument9 pagesInternational Lawavijit chowdhuryNo ratings yet

- Recognition of A State Is The Act by Which Another State Acknowledges That The Political Entity Recognized Possesses The Attributes of StatehoodDocument18 pagesRecognition of A State Is The Act by Which Another State Acknowledges That The Political Entity Recognized Possesses The Attributes of StatehoodanimeshNo ratings yet

- Jurisprudence Lecture 4: Early Legal PositivismDocument3 pagesJurisprudence Lecture 4: Early Legal Positivismcristina plesoiuNo ratings yet

- Public International Law NoteDocument67 pagesPublic International Law NoteKalewold GetuNo ratings yet

- RecognitionDocument15 pagesRecognitionNagalikar Law100% (1)

- Meaning of States by Frederick Tse Shyang ChenDocument17 pagesMeaning of States by Frederick Tse Shyang ChenTrish Wachuka GichaneNo ratings yet

- Development of US LawDocument4 pagesDevelopment of US LawKANYUKANo ratings yet

- On V and CLDocument5 pagesOn V and CLLionNo ratings yet

- 6.nov 13 - NLM PDFDocument16 pages6.nov 13 - NLM PDFminchanmonNo ratings yet

- Rail Technical Guide FinalDocument13 pagesRail Technical Guide FinalRidwan Akbar Jak JhonNo ratings yet

- Rueda Reading - Psychology - Teacherbeliefs - Accepted - Final PDFDocument37 pagesRueda Reading - Psychology - Teacherbeliefs - Accepted - Final PDFminchanmonNo ratings yet

- Motivational Theory PDFDocument36 pagesMotivational Theory PDFminchanmonNo ratings yet

- TECREC 100 001 ENERGY STANDARD VER 1 2 Final PDFDocument37 pagesTECREC 100 001 ENERGY STANDARD VER 1 2 Final PDFminchanmonNo ratings yet

- 24.oct .13 NLM PDFDocument16 pages24.oct .13 NLM PDFminchanmonNo ratings yet

- SECTION 20710 Flash Butt Rail Welding: Caltrain Standard SpecificationsDocument8 pagesSECTION 20710 Flash Butt Rail Welding: Caltrain Standard SpecificationsminchanmonNo ratings yet

- 1344249181201-Seniority of Inspectors PDFDocument10 pages1344249181201-Seniority of Inspectors PDFminchanmonNo ratings yet

- 17.oct .13 NLM PDFDocument16 pages17.oct .13 NLM PDFminchanmonNo ratings yet

- ORRTUmins310309 PDFDocument11 pagesORRTUmins310309 PDFminchanmonNo ratings yet

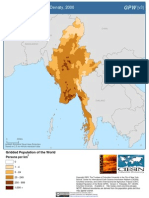

- Population Density, 2000: Gridded Population of The WorldDocument1 pagePopulation Density, 2000: Gridded Population of The WorldminchanmonNo ratings yet

- Ce4017 09Document31 pagesCe4017 09minchanmonNo ratings yet

- ChapterDocument91 pagesChapterminchanmonNo ratings yet