Professional Documents

Culture Documents

SD SDH

Uploaded by

snoopyboyOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

SD SDH

Uploaded by

snoopyboyCopyright:

Available Formats

History From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search This article is about the academic

discipline. For a general history of human be ings, see History of the world. For other uses, see History (disambiguation). Page semi-protected Historia by Nikolaos Gysis (1892) Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.[1] George Santayana History (from Greek ?st???a - historia, meaning "inquiry, knowledge acquired by investigation"[2]) is an umbrella term that relates to past events as well as th e discovery, collection, organization, and presentation of information about the se events. The term includes cosmic, geologic, and organic history, but is often generically implied to mean human history. Scholars who write about history are called historians. History can also refer to the academic discipline which uses a narrative to exam ine and analyse a sequence of past events, and objectively determine the pattern s of cause and effect that determine them.[3][4] Historians sometimes debate the nature of history and its usefulness by discussi ng the study of the discipline as an end in itself and as a way of providing "pe rspective" on the problems of the present.[3][5][6][7] Stories common to a particular culture, but not supported by external sources (s uch as the tales surrounding King Arthur) are usually classified as cultural her itage or legends, because they do not support the "disinterested investigation" required of the discipline of history.[8][9] Events occurring prior to written r ecord are considered prehistory. Herodotus, a 5th-century B.C. Greek historian is considered within the Western t radition to be the "father of history", and, along with his contemporary Thucydi des, helped form the foundations for the modern study of human history. Their wo rk continues to be read today and the divide between the culture-focused Herodot us and the military-focused Thucydides remains a point of contention or approach in modern historical writing. In the Eastern tradition, a state chronicle the S pring and Autumn Annals was known to be compiled from as early as 722 BCE althou gh only 2nd century BCE texts survived. Ancient influences have helped spawn variant interpretations of the nature of hi story which have evolved over the centuries and continue to change today. The mo dern study of history is wide-ranging, and includes the study of specific region s and the study of certain topical or thematical elements of historical investig ation. Often history is taught as part of primary and secondary education, and t he academic study of history is a major discipline in University studies. Contents 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Etymology Description History and prehistory Historiography Philosophy of history Historical methods Areas of study 7.1 Periods 7.2 Geographical locations

7.2.1 World 7.2.2 Regions 7.3 Military history 7.4 History of religion 7.5 Social history 7.5.1 Subfields 7.6 Cultural history 7.7 Diplomatic history 7.8 Economic history 7.9 Environmental history 7.10 World history 7.11 People's history 7.12 Historiometry 7.13 Gender history 7.14 Public history 8 Historians 9 The judgement of history 10 Pseudohistory 11 Teaching history 11.1 Bias in school teaching 12 See also 13 References 14 External links Etymology History by Frederick Dielman (1896) A derivation from *weid- "know" or "see" is attested as "the reconstructed etymo n wid-tor ["one who knows"] (compare to English wit) a suffixed zero-grade form of the PIE root *weid- 'see' and so is related to Greek eidnai, to know".[2][10] Ancient Greek ?st???a[11] (hstor) means "inquiry","knowledge from inquiry", or "j udge". It was in that sense that Aristotle used the word in his ?e?? ?? ??a ?st? ??a?[12] (Per T Za ?istorai "Inquiries about Animals"). The ancestor word ?st?? is a ttested early on in Homeric Hymns, Heraclitus, the Athenian ephebes' oath, and i n Boiotic inscriptions (in a legal sense, either "judge" or "witness", or simila r). The word entered the English language in 1390 with the meaning of "relation of i ncidents, story". In Middle English, the meaning was "story" in general. The res triction to the meaning "record of past events" arose in the late 15th century. It was still in the Greek sense that Francis Bacon used the term in the late 16t h century, when he wrote about "Natural History". For him, historia was "the kno wledge of objects determined by space and time", that sort of knowledge provided by memory (while science was provided by reason, and poetry was provided by fan tasy). In an expression of the linguistic synthetic vs. analytic/isolating dichotomy, E nglish like Chinese (? vs. ?) now designates separate words for human history an d storytelling in general. In modern German, French, and most Germanic and Roman ce languages, which are solidly synthetic and highly inflected, the same word is still used to mean both "history" and "story". The adjective historical is attested from 1661, and historic from 1669.[13] Historian in the sense of a "researcher of history" is attested from 1531. In al l European languages, the substantive "history" is still used to mean both "what happened with men", and "the scholarly study of the happened", the latter sense sometimes distinguished with a capital letter, "History", or the word historiog raphy.[12]

Description The title page to The Historians' History of the World Historians write in the context of their own time, and with due regard to the cu rrent dominant ideas of how to interpret the past, and sometimes write to provid e lessons for their own society. In the words of Benedetto Croce, "All history i s contemporary history". History is facilitated by the formation of a 'true disc ourse of past' through the production of narrative and analysis of past events r elating to the human race.[13] The modern discipline of history is dedicated to the institutional production of this discourse. All events that are remembered and preserved in some authentic form constitute t he historical record.[14] The task of historical discourse is to identify the so urces which can most usefully contribute to the production of accurate accounts of past. Therefore, the constitution of the historian's archive is a result of c ircumscribing a more general archive by invalidating the usage of certain texts and documents (by falsifying their claims to represent the 'true past'). The study of history has sometimes been classified as part of the humanities and at other times as part of the social sciences.[15] It can also be seen as a bri dge between those two broad areas, incorporating methodologies from both. Some i ndividual historians strongly support one or the other classification.[16] In th e 20th century, French historian Fernand Braudel revolutionized the study of his tory, by using such outside disciplines as economics, anthropology, and geograph y in the study of global history. Traditionally, historians have recorded events of the past, either in writing or by passing on an oral tradition, and have attempted to answer historical questi ons through the study of written documents and oral accounts. For the beginning, historians have also used such sources as monuments, inscriptions, and pictures . In general, the sources of historical knowledge can be separated into three ca tegories: what is written, what is said, and what is physically preserved, and h istorians often consult all three.[17] But writing is the marker that separates history from what comes before. Archaeology is a discipline that is especially helpful in dealing with buried si tes and objects, which, once unearthed, contribute to the study of history. But archaeology rarely stands alone. It uses narrative sources to complement its dis coveries. However, archaeology is constituted by a range of methodologies and ap proaches which are independent from history; that is to say, archaeology does no t "fill the gaps" within textual sources. Indeed, Historical Archaeology is a sp ecific branch of archaeology, often contrasting its conclusions against those of contemporary textual sources. For example, Mark Leone, the excavator and interp reter of historical Annapolis, Maryland, USA has sought to understand the contra diction between textual documents and the material record, demonstrating the pos session of slaves and the inequalities of wealth apparent via the study of the t otal historical environment, despite the ideology of "liberty" inherent in writt en documents at this time. There are varieties of ways in which history can be organized, including chronol ogically, culturally, territorially, and thematically. These divisions are not m utually exclusive, and significant overlaps are often present, as in "The Intern ational Women's Movement in an Age of Transition, 1830 1975." It is possible for h istorians to concern themselves with both the very specific and the very general , although the modern trend has been toward specialization. The area called Big History resists this specialization, and searches for universal patterns or tren ds. History has often been studied with some practical or theoretical aim, but a lso may be studied out of simple intellectual curiosity.[18] History and prehistory Human history

and prehistory ? before Homo (Pliocene) Three-age system prehistory Stone Age Lower Paleolithic Homo, Homo erectus Middle Paleolithic early Homo sapiens Upper Paleolithic behavioral modernity Neolithic civilization

Bronze Age Near East India Europe China Korea Iron Age Bronze Age collapse Ancient Near East India Europe China Japan Korea Nigeri Recorded History Ancient history Earliest records Postclassical Era Modern history Early Late Contemporary See also: Modernity and Futurology ?Future v t e Further information: Protohistory The history of the world is the memory of the past experience of Homo sapiens sa piens around the world, as that experience has been preserved, largely in writte n records. By "prehistory", historians mean the recovery of knowledge of the pas t in an area where no written records exist, or where the writing of a culture i s not understood. By studying painting, drawings, carvings, and other artifacts, some information can be recovered even in the absence of a written record. Sinc e the 20th century, the study of prehistory is considered essential to avoid his tory's implicit exclusion of certain civilizations, such as those of Sub-Saharan Africa and pre-Columbian America. Historians in the West have been criticized f or focusing disproportionately on the Western world.[19] In 1961, British histor ian E. H. Carr wrote: The line of demarcation between prehistoric and historical times is crossed when people cease to live only in the present, and become consciously interested both in their past and in their future. History begins with the handing down of tradition; and tradition means the carrying of the habits and lessons of the pa st into the future. Records of the past begin to be kept for the benefit of futu re generations.[20] This definition includes within the scope of history the strong interests of peo ples, such as Australian Aboriginals and New Zealand Maori in the past, and the oral records maintained and transmitted to succeeding generations, even before t heir contact with European civilization.

Historiography Main article: Historiography Historiography has a number of related meanings. Firstly, it can refer to how hi story has been produced: the story of the development of methodology and practic es (for example, the move from short-term biographical narrative towards long-te rm thematic analysis). Secondly, it can refer to what has been produced: a speci fic body of historical writing (for example, "medieval historiography during the 1960s" means "Works of medieval history written during the 1960s"). Thirdly, it may refer to why history is produced: the Philosophy of history. As a meta-leve l analysis of descriptions of the past, this third conception can relate to the first two in that the analysis usually focuses on the narratives, interpretation s, worldview, use of evidence, or method of presentation of other historians. Pr ofessional historians also debate the question of whether history can be taught as a single coherent narrative or a series of competing narratives. Philosophy of history History's philosophical questions What is the proper unit for the study of the human past the individual? The po lis? The civilization? The culture? Or the nation state? Are there broad patterns and progress? Are there cycles? Is human history ra ndom and devoid of any meaning? Main article: Philosophy of history Philosophy of history is a branch of philosophy concerning the eventual signific ance, if any, of human history. Furthermore, it speculates as to a possible tele ological end to its development that is, it asks if there is a design, purpose, di rective principle, or finality in the processes of human history. Philosophy of history should not be confused with historiography, which is the study of histor y as an academic discipline, and thus concerns its methods and practices, and it s development as a discipline over time. Nor should philosophy of history be con fused with the history of philosophy, which is the study of the development of p hilosophical ideas through time. Historical methods Further information: Historical method A depiction of the ancient Library of Alexandria Historical method basics The following questions are used by historians in modern work. When was the source, written or unwritten, produced (date)? Where was it produced (localization)? By whom was it produced (authorship)? From what pre-existing material was it produced (analysis)? In what original form was it produced (integrity)? What is the evidential value of its contents (credibility)? The first four are known as higher criticism; the fifth, lower criticism; and, t ogether, external criticism. The sixth and final inquiry about a source is calle d internal criticism. The historical method comprises the techniques and guidelines by which historian s use primary sources and other evidence to research and then to write history. Herodotus of Halicarnassus (484 BC ca.425 BC)[21] has generally been acclaimed a s the "father of history". However, his contemporary Thucydides (ca. 460 BC ca. 400 BC) is credited with having first approached history with a well-developed h istorical method in his work the History of the Peloponnesian War. Thucydides, u nlike Herodotus, regarded history as being the product of the choices and action

s of human beings, and looked at cause and effect, rather than as the result of divine intervention.[21] In his historical method, Thucydides emphasized chronol ogy, a neutral point of view, and that the human world was the result of the act ions of human beings. Greek historians also viewed history as cyclical, with eve nts regularly recurring.[22] There were historical traditions and sophisticated use of historical method in a ncient and medieval China. The groundwork for professional historiography in Eas t Asia was established by the Han Dynasty court historian known as Sima Qian (14 5 90 BC), author of the Shiji (Records of the Grand Historian). For the quality of his written work, Sima Qian is posthumously known as the Father of Chinese Hist oriography. Chinese historians of subsequent dynastic periods in China used his Shiji as the official format for historical texts, as well as for biographical l iterature.[citation needed] Saint Augustine was influential in Christian and Western thought at the beginnin g of the medieval period. Through the Medieval and Renaissance periods, history was often studied through a sacred or religious perspective. Around 1800, German philosopher and historian Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel brought philosophy and a more secular approach in historical study.[18] In the preface to his book, the Muqaddimah (1377), the Arab historian and early sociologist, Ibn Khaldun, warned of seven mistakes that he thought that historia ns regularly committed. In this criticism, he approached the past as strange and in need of interpretation. The originality of Ibn Khaldun was to claim that the cultural difference of another age must govern the evaluation of relevant histo rical material, to distinguish the principles according to which it might be pos sible to attempt the evaluation, and lastly, to feel the need for experience, in addition to rational principles, in order to assess a culture of the past. Ibn Khaldun often criticized "idle superstition and uncritical acceptance of histori cal data." As a result, he introduced a scientific method to the study of histor y, and he often referred to it as his "new science".[23] His historical method a lso laid the groundwork for the observation of the role of state, communication, propaganda and systematic bias in history,[24] and he is thus considered to be the "father of historiography"[25][26] or the "father of the philosophy of histo ry".[27] In the West historians developed modern methods of historiography in the 17th an d 18th centuries, especially in France and Germany. The 19th-century historian w ith greatest influence on methods was Leopold von Ranke in Germany. In the 20th century, academic historians focused less on epic nationalistic narr atives, which often tended to glorify the nation or great men, to more objective and complex analyses of social and intellectual forces. A major trend of histor ical methodology in the 20th century was a tendency to treat history more as a s ocial science rather than as an art, which traditionally had been the case. Some of the leading advocates of history as a social science were a diverse collecti on of scholars which included Fernand Braudel, E. H. Carr, Fritz Fischer, Emmanu el Le Roy Ladurie, Hans-Ulrich Wehler, Bruce Trigger, Marc Bloch, Karl Dietrich Bracher, Peter Gay, Robert Fogel, Lucien Febvre and Lawrence Stone. Many of the advocates of history as a social science were or are noted for their multi-disci plinary approach. Braudel combined history with geography, Bracher history with political science, Fogel history with economics, Gay history with psychology, Tr igger history with archaeology while Wehler, Bloch, Fischer, Stone, Febvre and L e Roy Ladurie have in varying and differing ways amalgamated history with sociol ogy, geography, anthropology, and economics. More recently, the field of digital history has begun to address ways of using computer technology to pose new ques tions to historical data and generate digital scholarship. In opposition to the claims of history as a social science, historians such as H

ugh Trevor-Roper, John Lukacs, Donald Creighton, Gertrude Himmelfarb and Gerhard Ritter argued that the key to the historians' work was the power of the imagina tion, and hence contended that history should be understood as an art. French hi storians associated with the Annales School introduced quantitative history, usi ng raw data to track the lives of typical individuals, and were prominent in the establishment of cultural history (cf. histoire des mentalits). Intellectual his torians such as Herbert Butterfield, Ernst Nolte and George Mosse have argued fo r the significance of ideas in history. American historians, motivated by the ci vil rights era, focused on formerly overlooked ethnic, racial, and socio-economi c groups. Another genre of social history to emerge in the post-WWII era was All tagsgeschichte (History of Everyday Life). Scholars such as Martin Broszat, Ian Kershaw and Detlev Peukert sought to examine what everyday life was like for ord inary people in 20th-century Germany, especially in the Nazi period. Marxist historians such as Eric Hobsbawm, E. P. Thompson, Rodney Hilton, Georges Lefebvre, Eugene D. Genovese, Isaac Deutscher, C. L. R. James, Timothy Mason, H erbert Aptheker, Arno J. Mayer and Christopher Hill have sought to validate Karl Marx's theories by analyzing history from a Marxist perspective. In response to the Marxist interpretation of history, historians such as Franois Furet, Richard Pipes, J. C. D. Clark, Roland Mousnier, Henry Ashby Turner and Robert Conquest have offered anti-Marxist interpretations of history.[citation needed] Feminist historians such as Joan Wallach Scott, Claudia Koonz, Natalie Zemon Davis, Sheil a Rowbotham, Gisela Bock, Gerda Lerner, Elizabeth Fox-Genovese, and Lynn Hunt ha ve argued for the importance of studying the experience of women in the past. In recent years, postmodernists have challenged the validity and need for the stud y of history on the basis that all history is based on the personal interpretati on of sources. In his 1997 book In Defence of History, Richard J. Evans, a profe ssor of modern history at Cambridge University, defended the worth of history. A nother defence of history from post-modernist criticism was the Australian histo rian Keith Windschuttle's 1994 book, The Killing of History. Areas of study Particular studies and fields These are approaches to history; not listed are histories of other fields, such as history of science, history of mathematics and history of philosophy. Ancient history : the study from the beginning of human history until the Ea rly Middle Ages. Atlantic history: the study of the history of people living on or near the A tlantic Ocean. Art History: the study of changes in and social context of art. Big History: study of history on a large scale across long time frames and e pochs through a multi-disciplinary approach. Chronology: science of localizing historical events in time. Comparative history: historical analysis of social and cultural entities not confined to national boundaries. Contemporary history: the study of historical events that are immediately re levant to the present time. Counterfactual history: the study of historical events as they might have ha ppened in different causal circumstances. Cultural history: the study of culture in the past. Digital History: the use of computing technologies to produce digital schola rship. Economic History: the study of economies in the past. Futurology: study of the future: researches the medium to long-term future o f societies and of the physical world. Intellectual history: the study of ideas in the context of the cultures that produced them and their development over time. Maritime history: the study of maritime transport and all the connected subj

ects. Modern history : the study of the Modern Times, the era after the Middle Age s. Military History: the study of warfare and wars in history and what is somet imes considered to be a sub-branch of military history, Naval History. Natural history: the study of the development of the cosmos, the Earth, biol ogy and interactions thereof. Paleography: study of ancient texts. People's history: historical work from the perspective of common people. Political history: the study of politics in the past. Psychohistory: study of the psychological motivations of historical events. Pseudohistory: study about the past that falls outside the domain of mainstr eam history (sometimes it is an equivalent of pseudoscience). Social History: the study of the process of social change throughout history . Universal history: basic to the Western tradition of historiography. Women's history: the history of female human beings. Gender history is relat ed and covers the perspective of gender. World History: the study of history from a global perspective. Periods Main article: Periodization Historical study often focuses on events and developments that occur in particul ar blocks of time. Historians give these periods of time names in order to allow "organising ideas and classificatory generalisations" to be used by historians. [28] The names given to a period can vary with geographical location, as can the dates of the start and end of a particular period. Centuries and decades are co mmonly used periods and the time they represent depends on the dating system use d. Most periods are constructed retrospectively and so reflect value judgments m ade about the past. The way periods are constructed and the names given to them can affect the way they are viewed and studied.[29] Geographical locations Particular geographical locations can form the basis of historical study, for ex ample, continents, countries and cities. Understanding why historic events took place is important. To do this, historians often turn to geography. Weather patt erns, the water supply, and the landscape of a place all affect the lives of the people who live there. For example, to explain why the ancient Egyptians develo ped a successful civilization, studying the geography of Egypt is essential. Egy ptian civilization was built on the banks of the Nile River, which flooded each year, depositing soil on its banks. The rich soil could help farmers grow enough crops to feed the people in the cities. That meant everyone did not have to far m, so some people could perform other jobs that helped develop the civilization. World Main article: History of the world World history is the study of major civilizations over the last 3000 years or so . It has led to highly controversial interpretations by Oswald Spengler and Arno ld J. Toynbee, among others. World history is especially important as a teaching field. It has increasingly entered the university curriculum in the U.S., in ma ny cases replacing courses in Western Civilization, that had a focus on Europe a nd the U.S. World history adds extensive new material on Asia, Africa and Latin America. Regions History of Africa begins with the first emergence of modern human beings on the continent, continuing into its modern present as a patchwork of diverse and politically developing nation states. History of the Americas is the collective history of North and South America

, including Central America and the Caribbean. History of North America is the study of the past passed down from gener ation to generation on the continent in the Earth's northern and western hemisph ere. History of Central America is the study of the past passed down from gen eration to generation on the continent in the Earth's western hemisphere. History of the Caribbean begins with the oldest evidence where 7,000-yea r-old remains have been found. History of South America is the study of the past passed down from gener ation to generation on the continent in the Earth's southern and western hemisph ere. History of Antarctica emerges from early Western theories of a vast continen t, known as Terra Australis, believed to exist in the far south of the globe. History of Australia start with the documentation of the Makassar trading wi th Indigenous Australians on Australia's north coast. History of New Zealand dates back at least 700 years to when it was discover ed and settled by Polynesians, who developed a distinct Maori culture centred on kinship links and land. History of the Pacific Islands covers the history of the islands in the Paci fic Ocean. History of Eurasia is the collective history of several distinct peripheral coastal regions: the Middle East, South Asia, East Asia, Southeast Asia, and Eur ope, linked by the interior mass of the Eurasian steppe of Central Asia and East ern Europe. History of Europe describes the passage of time from humans inhabiting t he European continent to the present day. History of Asia can be seen as the collective history of several distinc t peripheral coastal regions, East Asia, South Asia, and the Middle East linked by the interior mass of the Eurasian steppe. History of East Asia is the study of the past passed down from gener ation to generation in East Asia. History of the Middle East begins with the earliest civilizations in the region now known as the Middle East that were established around 3000 BC, i n Mesopotamia (Iraq). History of South Asia is the study of the past passed down from gene ration to generation in the Sub-Himalayan region. History of Southeast Asia has been characterized as interaction betw een regional players and foreign powers. Military history Main article: Military history Military history concerns warfare, strategies, battles, weapons, and the psychol ogy of combat. The "new military history" since the 1970s has been concerned wit h soldiers more than generals, with psychology more than tactics, and with the b roader impact of warfare on society and culture.[30] History of religion Main article: Religious history The history of religion has been a main theme for both secular and religious his torians for centuries, and continues to be taught in seminaries and academe. Lea ding journals include Church History, Catholic Historical Review, and History of Religions. Topics range widely from political and cultural and artistic dimensi ons, to theology and liturgy.[31] Every major country is covered,[32] and most s maller ones as well. Social history Main article: Social history Social history, sometimes called the new social history, is the field that inclu des history of ordinary people and their strategies and institutions for coping

with life.[33] In its "golden age" it was a major growth field in the 1960s and 1970s among scholars, and still is well represented in history departments. In t wo decades from 1975 to 1995, the proportion of professors of history in America n universities identifying with social history rose from 31% to 41%, while the p roportion of political historians fell from 40% to 30%.[34] In the history depar tments of British universities in 2007, of the 5723 faculty members, 1644 (29%) identified themselves with social history while political history came next with 1425 (25%).[35] The "old" social history before the 1960s was a hodgepodge of t opics without a central theme, and it often included political movements, like P opulism, that were "social" in the sense of being outside the elite system. Soci al history was contrasted with political history, intellectual history and the h istory of great men. English historian G. M. Trevelyan saw it as the bridging po int between economic and political history, reflecting that, "Without social his tory, economic history is barren and political history unintelligible."[36] Whil e the field has often been viewed negatively as history with the politics left o ut, it has also been defended as "history with the people put back in."[37] Subfields The chief subfields of social history include: Demographic history Black history History of education Ethnic history

Family history Labor history Rural history Urban history Cultural history Main article: Cultural history Cultural history replaced social history as the dominant form in the 1980s and 1 990s. It typically combines the approaches of anthropology and history to look a t language, popular cultural traditions and cultural interpretations of historic al experience. It examines the records and narrative descriptions of past knowle dge, customs, and arts of a group of people. How peoples constructed their memor y of the past is a major topic. Cultural history includes the study of art in so ciety as well is the study of images and human visual production (iconography).[ 38] Diplomatic history Main article: Diplomatic history Diplomatic history, sometimes referred to as "Rankian History"[39] in honor of L eopold von Ranke, focuses on politics, politicians and other high rulers and vie ws them as being the driving force of continuity and change in history. This typ e of political history is the study of the conduct of international relations be tween states or across state boundaries over time. This is the most common form of history and is often the classical and popular belief of what history should be. Economic history Main article: Economic history Although economic history has been well established since the late 19th century, in recent years academic studies have shifted more and more toward economics de partments and away from traditional history departments.[40] Environmental history

Main article: Environmental history Environmental history is a new field that emerged in the 1980s to look at the hi story of the environment, especially in the long run, and the impact of human ac tivities upon it.[41] World history Main article: World history World history is primarily a teaching field, rather than a research field. It ga ined popularity in the United States,[42] Japan[43] and other countries after th e 1980s with the realization that students need a broader exposure to the world as globalization proceeds. The World History Association publishes the Journal of World History every quart er since 1990.[44] The H-World discussion list[45] serves as a network of commun ication among practitioners of world history, with discussions among scholars, a nnouncements, syllabi, bibliographies and book reviews. People's history Main article: People's history A people's history is a type of historical work which attempts to account for hi storical events from the perspective of common people. A people's history is the history of the world that is the story of mass movements and of the outsiders. Individuals or groups not included in the past in other type of writing about hi story are the primary focus, which includes the disenfranchised, the oppressed, the poor, the nonconformists, and the otherwise forgotten people. This history a lso usually focuses on events occurring in the fullness of time, or when an over whelming wave of smaller events cause certain developments to occur. Historiometry Main article: Historiometry Historiometry is a historical study of human progress or individual personal cha racteristics, by using statistics to analyze references to eminent persons, thei r statements, behavior and discoveries in relatively neutral texts. Gender history Main article: Gender history Gender history is a sub-field of History and Gender studies, which looks at the past from the perspective of gender. It is in many ways, an outgrowth of women's history. Despite its relatively short life, Gender History (and its forerunner Women's History) has had a rather significant effect on the general study of his tory. Since the 1960s, when the initially small field first achieved a measure o f acceptance, it has gone through a number of different phases, each with its ow n challenges and outcomes. Although some of the changes to the study of history have been quite obvious, such as increased numbers of books on famous women or s imply the admission of greater numbers of women into the historical profession, other influences are more subtle. Public history Main article: Public history Public history describes the broad range of activities undertaken by people with some training in the discipline of history who are generally working outside of specialized academic settings. Public history practice has quite deep roots in the areas of historic preservation, archival science, oral history, museum curat orship, and other related fields. The term itself began to be used in the U.S. a nd Canada in the late 1970s, and the field has become increasingly professionali zed since that time. Some of the most common settings for public history are mus eums, historic homes and historic sites, parks, battlefields, archives, film and television companies, and all levels of government. Historians

Main article: List of historians Professional and amateur historians discover, collect, organize, and present inf ormation about past events. In lists of historians, historians can be grouped by order of the historical period in which they were writing, which is not necessa rily the same as the period in which they specialized. Chroniclers and annalists , though they are not historians in the true sense, are also frequently included . The judgement of history Since the 20th century, Western historians have disavowed the aspiration to prov ide the "judgement of history."[46] The goals of historical judgements or interp retations are separate to those of legal judgements, that need to be formulated quickly after the events and be final.[47] A related issue to that of the judgem ent of history is that of collective memory. Pseudohistory Main article: Pseudohistory Pseudohistory is a term applied to texts which purport to be historical in natur e but which depart from standard historiographical conventions in a way which un dermines their conclusions. Closely related to deceptive historical revisionsm, works which draw controversial conclusions from new, speculative, or disputed hi storical evidence, particularly in the fields of national, political, military, and religious affairs, are often rejected as pseudohistory. Teaching history From the origins of national school systems in the 19th century, the teaching of history to promote national sentiment has been a high priority. In the United S tates after World War I, a strong movement emerged at the university level to te ach courses in Western Civilization, so as to give students a common heritage wi th Europe. In the U.S. after 1980 attention increasingly moved toward teaching w orld history or requiring students to take courses in non-western cultures, to p repare students for life in a globalized economy.[48] At the university level, historians debate the question of whether history belon gs more to social science or to the humanities. Many view the field from both pe rspectives. The teaching of history in French schools was influenced by the Nouvelle histoir e as disseminated after the 1960s by Cahiers pdagogiques and Enseignement and oth er journals for teachers. Also influential was the Institut national de recherch e et de documentation pdagogique, (INRDP). Joseph Leif, the Inspector-general of teacher training, said pupils children should learn about historians approaches a s well as facts and dates. Louis Franois, Dean of the History/Geography group in the Inspectorate of National Education advised that teachers should provide hist oric documents and promote "active methods" which would give pupils "the immense happiness of discovery." Proponents said it was a reaction against the memoriza tion of names and dates that characterized teaching and left the students bored. Traditionalists protested loudly it was a postmodern innovation that threatened to leave the youth ignorant of French patriotism and national identity.[49] Bias in school teaching In most countries history textbook are tools to foster nationalism and patriotis m, and give students the official line about national enemies.[50] In many countries history textbooks are sponsored by the national government and are written to put the national heritage in the most favorable light. For examp le, in Japan, mention of the Nanking Massacre has been removed from textbooks an d the entire World War II is given cursory treatment. Other countries have compl ained.[51] It was standard policy in communist countries to present only a rigid

Marxist historiography.[52][53] According to sociologist James Loewen, in the United States the history of the A merican Civil War some places has been phrased to avoid giving offense to white Southerners[54] and blacks.[page needed][need quotation to verify] Academic historians have often fought against the politicization of the textbook s, sometimes with success.[55][56] In 21st-century Germany, the history curriculum is controlled by the 16 states, and is characterized not by superpatriotism but rather by an "almost pacifistic and deliberately unpatriotic undertone" and reflects "principles formulated by i nternational organizations such as UNESCO or the Council of Europe, thus oriente d towards human rights, democracy and peace." The result is that "German textboo ks usually downplay national pride and ambitions and aim to develop an understan ding of citizenship centred on democracy, progress, human rights, peace, toleran ce and Europeanness."[57] See also Book icon Book: History Portal icon History portal Main articles: Outline of history and Glossary of history Annal Auxiliary sciences of history Bibliography of history Big History Chronicle Historian List of historians History Journal Historiography List of history journals Timeline of world history References ^ George Santayana, "The Life of Reason", Volume One, p. 82, BiblioLife, ISB N 978-0-559-47806-2 ^ a b Joseph, Brian (Ed.); Janda, Richard (Ed.) (2008). The Handbook of Hist orical Linguistics. Blackwell Publishing (published 30 December 2004). p. 163. I SBN 978-1-4051-2747-9 ^ a b Professor Richard J. Evans (2001). "The Two Faces of E.H. Carr". Histo ry in Focus, Issue 2: What is History?. University of London. Retrieved 10 Novem ber 2008. ^ Professor Alun Munslow (2001). "What History Is". History in Focus, Issue 2: What is History?. University of London. Retrieved 10 November 2008. ^ Tosh, John (2006). The Pursuit of History (4th ed.). Pearson Education Lim ited. ISBN 1-4058-2351-8.p 52 ^ Peter N. Stearns, Peters Seixas, Sam Wineburg (eds.), ed. (2000). "Introdu ction". Knowing Teaching and Learning History, National and International Perspe ctives. New York & London: New York University Press. p. 6. ISBN 0-8147-8141-1. ^ Nash l, Gary B. (2000). "The "Convergence" Paradigm in Studying Early Amer ican History in Schools". In Peter N. Stearns, Peters Seixas, Sam Wineburg (eds. ). Knowing Teaching and Learning History, National and International Perspective s. New York & London: New York University Press. pp. 102 115. ISBN 0-8147-8141-1. ^ Seixas, Peter (2000). "Schweigen! die Kinder!". In Peter N. Stearns, Peter s Seixas, Sam Wineburg (eds.). Knowing Teaching and Learning History, National a

nd International Perspectives. New York & London: New York University Press. p. 24. ISBN 0-8147-8141-1. ^ Lowenthal, David (2000). "Dilemmas and Delights of Learning History". In P eter N. Stearns, Peters Seixas, Sam Wineburg (eds.). Knowing Teaching and Learni ng History, National and International Perspectives. New York & London: New York University Press. p. 63. ISBN 0-8147-8141-1. ^ "Online Etymology Dictionary". Etymonline.com. Retrieved 2010-05-16. ^ ?st???a ^ a b Ferrater-Mora, Jos. Diccionario de Filosofia. Barcelona: Editorial Arie l, 1994. ^ a b Whitney, W. D. The Century dictionary; an encyclopedic lexicon of the English language. New York: The Century Co, 1889. ^ WordNet Search 3.0, "History". ^ Scott Gordon and James Gordon Irving, The History and Philosophy of Social Science. Routledge 1991. Page 1. ISBN 0-415-05682-9 ^ Ritter, H. (1986). Dictionary of concepts in history. Reference sources fo r the social sciences and humanities, no. 3. Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press. Pa ge 416. ^ Michael C. Lemon (1995).The Discipline of History and the History of Thoug ht. Routledge. Page 201. ISBN 0-415-12346-1 ^ a b Graham, Gordon (1997). "Chapter 1". The Shape of the Past. Oxford Univ ersity. ^ Jack Goody (2007) The Theft of History (from Google Books) ^ Carr, Edward H. (1961). What is History?, p.108, ISBN 0-14-020652-3 ^ a b Lamberg-Karlovsky, C. C. and Jeremy A. Sabloff (1979). Ancient Civiliz ations: The Near East and Mesoamerica. Benjamin-Cummings Publishing. p. 5. ISBN 0-88133-834-6. ^ Lamberg-Karlovsky, C. C. and Jeremy A. Sabloff (1979). Ancient Civilizatio ns: The Near East and Mesoamerica. Benjamin-Cummings Publishing. p. 6. ISBN 0-88 133-834-6. ^ Ibn Khaldun, Franz Rosenthal, N. J. Dawood (1967), The Muqaddimah: An Intr oduction to History, p. x, Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-01754-9. ^ H. Mowlana (2001). "Information in the Arab World", Cooperation South Jour nal 1. ^ Salahuddin Ahmed (1999). A Dictionary of Muslim Names. C. Hurst & Co. Publ ishers. ISBN 1-85065-356-9. ^ Enan, Muhammed Abdullah (2007). Ibn Khaldun: His Life and Works. The Other Press. p. v. ISBN 983-9541-53-6 ^ Dr. S. W. Akhtar (1997). "The Islamic Concept of Knowledge", Al-Tawhid: A Quarterly Journal of Islamic Thought & Culture 12 (3). ^ Marwick, Arthur (1970). The Nature of History. The Macmillian Press LTD. p . 169. ^ Tosh, John (2006). The Pursuit of History. Pearson Education Limited. pp. 168 169. ^ Pavkovic, Michael; Morillo, Stephen (2006). What is Military History?. Oxf ord: Polity Press (published 31 July 2006). pp. 3 4. ISBN 978-0-7456-3390-9 ^ Eric Cochrane, "What Is Catholic Historiography?" Catholic Historical Revi ew Vol. 61, No. 2 (April , 1975), pp. 169-190 in JSTOR ^ For example see Sofia Boesch Gajano and Tommaso Cali, "Italian religious hi storiography in the 1990s," Journal of Modern Italian Studies, Fall 1998, Vol. 3 Issue 3, pp 293-306 ^ Peter Stearns, ed. Encyclopedia of Social History (1994) ^ Diplomatic dropped from 5% to 3%, economic history from 7% to 5%, and cult ural history grew from 14% to 16%. Based on full-time professors in U.S. history departments. Stephen H. Haber, David M. Kennedy, and Stephen D. Krasner, "Broth ers under the Skin: Diplomatic History and International Relations," Internation al Security, Vol. 22, No. 1 (Summer, 1997), pp. 34-43 at p. 4 2; online at JSTOR ^ See "Teachers of History in the Universities of the UK 2007 - listed by re search interest" ^ G. M. Trevelyan (1973). "Introduction". English Social History: A Survey o

f Six Centuries from Chaucer to Queen Victoria. Book Club Associates. p. i. ISBN 0-582-48488-X. ^ Mary Fulbrook (2005). "Introduction: The people's paradox". The People's S tate: East German Society from Hitler to Honecker. London: Yale University Press . p. 17. ISBN 978-0-300-14424-6. ^ The first World Dictionnary of Images: Laurent Gervereau (ed.), "Dictionna ire mondial des images", Paris, Nouveau monde, 2006, 1120p, ISBN : 978-2-84736-1 85-8. (with 275 specialists from all continents, all specialities, all periods f rom Prehistory to nowadays) ; Laurent Gervereau, "Images, une histoire mondiale" , Paris, Nouveau monde, 2008, 272p., ISBN : 978-2-84736-362-3 ^ Burke, P. (1998). New perspectives on historical writing. University Park, Pa: Pennsylvania State University Press. Page 3. ^ Robert Whaples, "Is Economic History a Neglected Field of Study?," Histori cally Speaking (April 2010) v. 11#2 pp 17-20, with responses pp 20-27 ^ J. D. Hughes, What is Environmental History (2006) excerpt and text search ^ Ainslie T. Embree and Carol Gluck, eds., Asia in Western and World History : A Guide for Teaching (M.E. Sharpe, 1997) ^ Shigeru Akita, "World History and the Emergence of Global History in Japan ,"Chinese Studies in History, Spring 2010, Vol. 43 Issue 3, pp 84-96 ^ see JWH Website ^ see H-World ^ Curran, Vivian Grosswald (2000) Herder and the Holocaust: A Debate About D ifference and Determinism in the Context of Comparative Law in F. C. DeCoste, Be rnard Schwartz (eds.) Holocaust's Ghost: Writings on Art, Politics, Law and Educ ation pp.413-5 ^ Curran, Vivian Grosswald (2000) Herder and the Holocaust: A Debate About D ifference and Determinism in the Context of Comparative Law in F. C. DeCoste, Be rnard Schwartz (eds.) Holocaust's Ghost: Writings on Art, Politics, Law and Educ ation p.415 ^ Jacqueline Swansinger, "Preparing Student Teachers for a World History Cur riculum in New York," History Teacher, (November 2009), 43#1 pp 87-96 ^ Abby Waldman, " The Politics of History Teaching in England and France dur ing the 1980s," History Workshop Journal Issue 68, Autumn 2009 pp. 199-221 onlin e ^ Jason Nicholls, ed. School History Textbooks across Cultures: Internationa l Debates and Perspectives (2006) ^ Claudia Schneider, "The Japanese History Textbook Controversy in East Asia n Perspective," Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, May 2008, Vol. 617, pp 107-122 ^ "Problems of Teaching Contemporary Russian History," Russian Studies in Hi story, Winter 2004, Vol. 43 Issue 3, pp 61-62 ^ "Blackwell-Synergy.com". Blackwell-Synergy.com. Retrieved 2010-05-16. ^ James W. Loewen, Lies My Teacher Told Me: Everything Your American History Textbook Got Wrong, (1996) ^ "Teaching History in Schools: the Politics of Textbooks in India," History Workshop Journal, April 2009, Issue 67, pp 99-110 ^ Tatyana Volodina, "Teaching History in Russia After the Collapse of the US SR," History Teacher, February 2005, Vol. 38 Issue 2, pp 179-188 ^ Simone Lssig and Karl Heinrich Pohl, "History Textbooks and Historical Scho larship in Germany," History Workshop Journal Issue 67, Spring 2009 pp 128-9 onl ine at project MUSE External links Find more about History at Wikipedia's sister projects Definitions and translations from Wiktionary Media from Commons Learning resources from Wikiversity News stories from Wikinews Quotations from Wikiquote Source texts from Wikisource

Textbooks from Wikibooks Best history sites .net BBC History Site Internet History Sourcebooks Project See also Internet History Sourcebooks P roject. Collections of public domain and copy-permitted historical texts for edu cational use The History Channel Online History Channel UK [show] v t e Social sciences [show] v t e Humanities [show] v t e Time [show] v t e Chronology Categories: History Auxiliary sciences of history Navigation menu Create account Log in Article Talk Read View source View history Main page Contents Featured content

Current events Random article Donate to Wikipedia Interaction Help About Wikipedia Community portal Recent changes Contact Wikipedia Toolbox Print/export Languages Afrikaans Alemannisch ???? nglisc ??????? Aragons Armneashce Arpetan ??????? Asturianu Avae'? Aymar aru Az?rbaycanca Bamanankan ????? Bn-lm-g Basa Banyumasan ????????? ?????????? ?????????? (???????????)? ????????? Boarisch ??????? Bosanski Brezhoneg ?????? Catal ??????? Cebuano Cesky ChiShona Corsu Cymraeg Dansk Deitsch Deutsch Eesti ???????? Emilin e rumagnl Espaol Esperanto Estremeu Euskara ?????

Fiji Hindi Froyskt Franais Frysk Furlan Gaeilge Gaelg Gidhlig Galego ?? ??????? Hak-k-fa ??? ??????? ?????? Hrvatski Ido Igbo Ilokano Bahasa Indonesia Interlingua Interlingue ??????/inuktitut ???? IsiXhosa slenska Italiano ????? Basa Jawa Kalaallisut ????? ????????-??????? ??????? ??????? Kernowek Kiswahili ???? Kreyl ayisyen Kurd ???????? Ladino Latgalu Latina Latvie u Ltzebuergesch Lietuviu Ligure Limburgs Lojban Lumbaart Magyar ?????????? Malagasy ?????? Malti ????? ???? ???????? Bahasa Melayu Mng-de?ng-ng?

Mirands ?????? ?????????? Nahuatl Nederlands Nedersaksies ?????? ????? ???? ??? Nordfriisk Norsk bokml Norsk nynorsk Nouormand Novial Occitan ???? ????? O?zbekcha ?????? Plzisch ?????? Papiamentu ???? ????????? Picard Tok Pisin Plattdtsch Polski ???t?a?? Portugus Romna Runa Simi ?????????? ??????? ???? ???? ????????? Sardu Scots Seeltersk Sesotho sa Leboa Shqip Sicilianu Simple English Slovencina Sloven cina ?????????? / ?????????? Slunski Soomaaliga ????? ?????? / srpski Srpskohrvatski / ?????????????? Basa Sunda Suomi Svenska Tagalog ????? Taqbaylit Tarandne ???????/tatara ?????? ???

?????? Trke Trkmene ?????????? ???? ???????? / Uyghurche Vneto Vepsn kel Ti?ng Vi?t Volapk Vro ?? Winaray Wolof ?????? Yorb ?? Zeuws emaite ka ?? Edit links This page was last modified on 5 June 2013 at 14:42. Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License; additional terms may apply. By using this site, you agree to the Terms of Use a nd Privacy Policy. Wikipedia is a registered trademark of the Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., a nonprofit organization. Privacy policy About Wikipedia Disclaimers Contact Wikipedia Mobile view Wikimedia Foundation Powered by MediaWiki

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Sound 2.foo - DRDocument1 pageSound 2.foo - DRsnoopyboyNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- TextDocument8 pagesTextsnoopyboyNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Id, Ego and Super-EgoDocument9 pagesId, Ego and Super-Egosnoopyboy100% (2)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Pollen WikipediaDocument10 pagesPollen WikipediasnoopyboyNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- TextDocument10 pagesTextsnoopyboyNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- TextDocument7 pagesTextsnoopyboyNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Upload A Document For Free Download Access.: Select Files From Your Computer or Choose Other Ways To Upload BelowDocument1 pageUpload A Document For Free Download Access.: Select Files From Your Computer or Choose Other Ways To Upload BelowChong ChongNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- TextDocument10 pagesTextsnoopyboyNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Upload A Document For Free Access.: Select Files From Your Computer or Choose Other Ways To Upload BelowDocument1 pageUpload A Document For Free Access.: Select Files From Your Computer or Choose Other Ways To Upload Belowdejan.strbacNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- TextDocument2 pagesTextsnoopyboyNo ratings yet

- TextDocument2 pagesTextsnoopyboyNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- TextDocument6 pagesTextsnoopyboyNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Upload A Document For Free Access.: Select Files From Your Computer or Choose Other Ways To Upload BelowDocument1 pageUpload A Document For Free Access.: Select Files From Your Computer or Choose Other Ways To Upload Belowdejan.strbacNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Upload A Document For Free Access.: Select Files From Your Computer or Choose Other Ways To Upload BelowDocument1 pageUpload A Document For Free Access.: Select Files From Your Computer or Choose Other Ways To Upload Belowdejan.strbacNo ratings yet

- UujkpyDocument3 pagesUujkpysnoopyboyNo ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- JoupyDocument3 pagesJoupysnoopyboyNo ratings yet

- AyeesDocument8 pagesAyeessnoopyboyNo ratings yet

- IIDocument2 pagesIIsnoopyboyNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- AyDocument7 pagesAysnoopyboyNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- TomcruseDocument1 pageTomcrusesnoopyboyNo ratings yet

- LlmoupyDocument2 pagesLlmoupysnoopyboyNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- RrwmoupyDocument3 pagesRrwmoupysnoopyboyNo ratings yet

- WwmoupyDocument2 pagesWwmoupysnoopyboyNo ratings yet

- FlmmoupyDocument2 pagesFlmmoupysnoopyboyNo ratings yet

- FopyDocument1 pageFopysnoopyboyNo ratings yet

- DllmoupyDocument2 pagesDllmoupysnoopyboyNo ratings yet

- FlerdpyDocument2 pagesFlerdpysnoopyboyNo ratings yet

- FloupyDocument2 pagesFloupysnoopyboyNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- SdfopyDocument1 pageSdfopysnoopyboyNo ratings yet

- SdfopyDocument1 pageSdfopysnoopyboyNo ratings yet

- PART I. Basic Consideration in MAS and Consulting PracticeDocument18 pagesPART I. Basic Consideration in MAS and Consulting PracticeErickk EscanooNo ratings yet

- Heraclitus - The First Western HolistDocument12 pagesHeraclitus - The First Western HolistUri Ben-Ya'acovNo ratings yet

- HUU001-لغة انجليزية فنيةDocument102 pagesHUU001-لغة انجليزية فنيةAlaa SaedNo ratings yet

- Thesis Listening Skill and Reading SkillDocument40 pagesThesis Listening Skill and Reading SkillRuby M. Omandac100% (1)

- Senior High School Student Permanent Record: Republic of The Philippines Department of EducationDocument9 pagesSenior High School Student Permanent Record: Republic of The Philippines Department of EducationJoshua CorpuzNo ratings yet

- Life Cycle Costing PDFDocument25 pagesLife Cycle Costing PDFItayi NjaziNo ratings yet

- Advocacy and Campaigns Against Drug UseDocument4 pagesAdvocacy and Campaigns Against Drug UseaudreiNo ratings yet

- Engineeringstandards 150416152325 Conversion Gate01Document42 pagesEngineeringstandards 150416152325 Conversion Gate01Dauødhårø Deivis100% (2)

- Manuel P. Albaño, Ph. D., Ceso VDocument5 pagesManuel P. Albaño, Ph. D., Ceso VMJNo ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- FDNACCT Full-Online Syllabus - 1T2021Document7 pagesFDNACCT Full-Online Syllabus - 1T2021Ken 77No ratings yet

- Présentation Bootcamp 1 orDocument31 pagesPrésentation Bootcamp 1 orwalid laqrafiNo ratings yet

- Solution Manual For Creative Editing 6th EditionDocument5 pagesSolution Manual For Creative Editing 6th EditionDan Holland100% (34)

- Graduation - Speech 2Document2 pagesGraduation - Speech 2Jack Key Chan Antig100% (1)

- Conduct Surveysobservations ExperimentDocument20 pagesConduct Surveysobservations ExperimentkatecharisseaNo ratings yet

- Health Equity: Ron Chapman, MD, MPH Director and State Health Officer California Department of Public HealthDocument20 pagesHealth Equity: Ron Chapman, MD, MPH Director and State Health Officer California Department of Public HealthjudemcNo ratings yet

- NCM 103 Lec Week 1 Midterm What Is NursingDocument10 pagesNCM 103 Lec Week 1 Midterm What Is NursingKhream Harvie OcampoNo ratings yet

- Shiela Mae S. Espina: ObjectiveDocument2 pagesShiela Mae S. Espina: ObjectiveJude Bon AlbaoNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan PeDocument7 pagesLesson Plan PeSweet Angelie ManualesNo ratings yet

- Balagtas National Agricultural High School: Tel. or Fax Number 044 815 55 49Document4 pagesBalagtas National Agricultural High School: Tel. or Fax Number 044 815 55 49Cezar John SantosNo ratings yet

- The Effectiveness of Practical Work in Physics To Improve Students' Academic Performances PDFDocument16 pagesThe Effectiveness of Practical Work in Physics To Improve Students' Academic Performances PDFGlobal Research and Development ServicesNo ratings yet

- ID 333 VDA 6.3 Upgrade Training ProgramDocument2 pagesID 333 VDA 6.3 Upgrade Training ProgramfauzanNo ratings yet

- Islamization Abdulhameed Abo SulimanDocument7 pagesIslamization Abdulhameed Abo SulimanMohammed YahyaNo ratings yet

- Soi For Nor Fo1 BugagonDocument4 pagesSoi For Nor Fo1 BugagonCsjdm Bfp BulacanNo ratings yet

- FARNACIO-REYES RA8972 AQualitativeandPolicyEvaluationStudyDocument16 pagesFARNACIO-REYES RA8972 AQualitativeandPolicyEvaluationStudyJanelle BautistaNo ratings yet

- Business Math - Q2 - M3Document12 pagesBusiness Math - Q2 - M3Real GurayNo ratings yet

- Syllabus: Cambridge IGCSE First Language English 0500Document36 pagesSyllabus: Cambridge IGCSE First Language English 0500Kanika ChawlaNo ratings yet

- Qualification Template V3Document52 pagesQualification Template V3DR-Muhammad ZahidNo ratings yet

- Cae - Gold PlusDocument4 pagesCae - Gold Plusalina solcanNo ratings yet

- Structural Functionalism of MediaDocument3 pagesStructural Functionalism of Mediasudeshna860% (1)

- AWS Certified Developer Associate Updated June 2018 Exam GuideDocument3 pagesAWS Certified Developer Associate Updated June 2018 Exam GuideDivyaNo ratings yet

- The Pursuit of Happyness: The Life Story That Inspired the Major Motion PictureFrom EverandThe Pursuit of Happyness: The Life Story That Inspired the Major Motion PictureNo ratings yet

- When and Where I Enter: The Impact of Black Women on Race and Sex in AmericaFrom EverandWhen and Where I Enter: The Impact of Black Women on Race and Sex in AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (33)

- The Devil You Know: A Black Power ManifestoFrom EverandThe Devil You Know: A Black Power ManifestoRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (10)

- The Masonic Myth: Unlocking the Truth About the Symbols, the Secret Rites, and the History of FreemasonryFrom EverandThe Masonic Myth: Unlocking the Truth About the Symbols, the Secret Rites, and the History of FreemasonryRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (14)

- The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America's Great MigrationFrom EverandThe Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America's Great MigrationRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (1573)

- The Original Black Elite: Daniel Murray and the Story of a Forgotten EraFrom EverandThe Original Black Elite: Daniel Murray and the Story of a Forgotten EraRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (6)

- Bound for Canaan: The Epic Story of the Underground Railroad, America's First Civil Rights Movement,From EverandBound for Canaan: The Epic Story of the Underground Railroad, America's First Civil Rights Movement,Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (69)

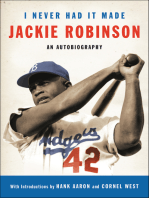

- I Never Had It Made: An AutobiographyFrom EverandI Never Had It Made: An AutobiographyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (38)

- Black Pearls: Daily Meditations, Affirmations, and Inspirations for African-AmericansFrom EverandBlack Pearls: Daily Meditations, Affirmations, and Inspirations for African-AmericansRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)