Professional Documents

Culture Documents

J. Clin. Microbiol.-2008-Lagacé-Wiens-804-6

Uploaded by

Muhamad AfidinCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

J. Clin. Microbiol.-2008-Lagacé-Wiens-804-6

Uploaded by

Muhamad AfidinCopyright:

Available Formats

Gardnerella vaginalis Bacteremia in a Previously Healthy Man: Case Report and Characterization of the Isolate

Philippe R. S. Lagac-Wiens, Betty Ng, Aleisha Reimer, Tamara Burdz, Deborah Wiebe and Kathryn Bernard J. Clin. Microbiol. 2008, 46(2):804. DOI: 10.1128/JCM.01545-07. Published Ahead of Print 5 December 2007. Downloaded from http://jcm.asm.org/ on September 12, 2013 by guest

Updated information and services can be found at: http://jcm.asm.org/content/46/2/804 These include:

REFERENCES

This article cites 14 articles, 6 of which can be accessed free at: http://jcm.asm.org/content/46/2/804#ref-list-1 Receive: RSS Feeds, eTOCs, free email alerts (when new articles cite this article), more

CONTENT ALERTS

Information about commercial reprint orders: http://journals.asm.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtml To subscribe to to another ASM Journal go to: http://journals.asm.org/site/subscriptions/

JOURNAL OF CLINICAL MICROBIOLOGY, Feb. 2008, p. 804806 0095-1137/08/$08.000 doi:10.1128/JCM.01545-07 Copyright 2008, American Society for Microbiology. All Rights Reserved.

Vol. 46, No. 2

CASE REPORTS

Gardnerella vaginalis Bacteremia in a Previously Healthy Man: Case Report and Characterization of the Isolate

Philippe R. S. Lagace -Wiens,1 Betty Ng,2 Aleisha Reimer,2 Tamara Burdz,2 Deborah Wiebe,2 and Kathryn Bernard1,2*

Department of Medical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, Faculty of Medicine, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Canada,1 and Department of Special Bacteriology, Division of Emerging Pathogens, National Microbiology Laboratory, Winnipeg, Canada2

Received 2 August 2007/Returned for modication 30 September 2007/Accepted 16 November 2007

Downloaded from http://jcm.asm.org/ on September 12, 2013 by guest

Gardnerella vaginalis in women causes vaginitis or infections in other sites, such as the urinary tract, but is an infrequent cause of bacteremia. Bacteremia in men is very rare and is typically associated with immunocompromised states. Here we describe G. vaginalis bacteremia in a previously healthy man with renal calculi and urosepsis.

CASE REPORT A 41-year-old male roofer with no prior medical problems presented with sudden onset of left ank pain. The pain was colicky in nature and not accompanied by fever, chills, urgency, or dysuria. A physical examination at the time of presentation was unremarkable. A computed tomography scan of the abdomen revealed a 6.5-mm kidney stone in the midpole of the kidney and a 3-mm calculus at the left vesicoureteric junction. Obstructive uropathy and perinephric stranding were noted. Urine biochemistry revealed slight hemoglobinuria. The patient underwent ureteroscopy the following day, and as no infection was thought to be present, no antibiotics were given. The distal ureteric calculus was not seen and was assumed to have passed spontaneously. Follow-up imaging demonstrated only the larger proximal stone. The patient was discharged from the hospital, but he returned 2 days later with worse ank pain. The computed tomography scan was repeated, and it demonstrated a 4-mm stone in the proximal left ureter, with small fragments remaining in the midpole of the kidney. Additional investigations revealed a leukocyte count of 16.0 109 cells/liter (normal range, 4 109 to 11 109 cells/liter) with a predominance of neutrophils (absolute count, 12.6 109 cells/ liter; normal count, 2 109 to 5 109 cells/liter). Creatinine was elevated at 148 mol/liter (normal range, 70 to 110 mol/ liter). The patient was readmitted for a repeat ureteroscopy. Prior to this procedure, the patient was febrile, with a temperature of 39.1C and rigors. He appeared well otherwise, and his physical examination, including blood pressure, was unremarkable. Ciprooxacin (400 mg intravenously every 12 h) was empirically started for presumed urosepsis. The patients complete blood count was normal, and cultures of urine and blood

* Corresponding author. Mailing address: National Microbiology Laboratory, 1015 Arlington Street, Winnipeg, Manitoba R3E 3R2, Canada. Phone: (204) 789-2135. Fax: (204) 784-7509. E-mail: kathy_bernard @phac-aspc.gc.ca. Published ahead of print on 5 December 2007. 804

(two sets, with 20 ml from one site for anaerobe and aerobic cultures and 10 ml from a second site for an aerobic bottle) were taken prior to initiation of antimicrobial therapy. The quantitative urine culture revealed 6.5 107 CFU/liter of a ciprooxacin-sensitive strain of Escherichia coli. On the fth day of incubation, the aerobic blood culture from the rst set was agged positive by the automated BacT/Alert system. A subculture of the second blood culture set revealed the same organism. The hospital laboratory was unable to achieve a denitive identication of the blood culture isolate, so the isolate was sent to a reference center. The patient underwent a repeat ureteroscopy with lithotripsy and an extraction of the proximal stone. A ureteric stent was inserted, and it was removed the following week. The patient was treated with a 10-day course of oral ciprooxacin and had no recurrences or sequelae. An initial Gram stain of the blood culture revealed pleomorphic, gram-negative coccobacilli. The blood culture isolate was plated on in-house-prepared 5% sheep blood agar (base agar from Oxoid Ltd., Ottawa, Ontario, Canada; sheep blood from Quad Five, Ryegate, MT) and chocolate agar (Oxoid) in 5% CO2-MacConkey agar (Oxoid) for aerobic incubation, and brucella agar with vitamin K (Oxoid) for anaerobic incubation. After 48 h of incubation, small gray colonies were observed on the chocolate agar, with poor growth of gray, nonhemolytic colonies found on the sheep blood agar. Gram staining revealed similar gram-negative coccobacilli. Catalase and rapid oxidase tests were negative, so the isolate was referred to the Canadian National Microbiology Laboratory (NML) as a suspected isolate of Francisella tularensis. Rapid molecular testing indicated that the isolate was not F. tularensis, and further testing was undertaken, with the strain being assigned NML Special Bacteriology identier no. 060420. A repeat Gram staining suggested that the organism was gram-positive or gram-variable short rods. The colonies were pinpoint (after 2 days) to small (1 mm) and translucent (after 4 days), with no hemolysis observed after growth on 5% sheep blood agar. The

VOL. 46, 2008

CASE REPORTS

805

isolate did have a narrow zone of beta-hemolysis after 4 days on vaginalis agar, which contains human red blood cells (PML Microbiologicals, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada). The isolate grew well at 37C in 5% CO2 under strictly anaerobic conditions, but no growth was observed in air at 25C, 37C, or 42C. Biochemical testing using carbohydrate (CHO) tube sugars, metabolic products of fermentation, cellular fatty acid (CFA) composition analysis, and 16S rRNA gene sequencing was performed as previously described (3, 4). Acid was observed in CHO sugars containing galactose, glucose, glycogen, maltose, sucrose, and xylose. The strain produced lipase and was negative for fermentation of fructose, glycerol, lactose, mannitol, mannose, rafnose, ribose, salicin, and trehalose. Tests for the utilization or hydrolysis of citrate, esculin, and urea, nitrate reduction, the presence of indole, staining with methyl red, and gelatin and lecithinase production, as well as the VogesProskauer test, were all negative. An API Strep strip used as described by the manufacturer (bioMe rieux, Montreal, Quebec, Canada) generated a code of 2050001, which corresponds to a 99.8% condence value of identication of Gardnerella vaginalis, including the utilization of starch. These reactions are consistent with the identication of G. vaginalis (6). The major metabolic product was acetic acid. The CFA composition was consistent with those observed for G. vaginalis strains referred to the NML as well as for the type strain ATCC 14018, with CFAs C14:0, C16:0, 18:19c, and C18:0 predominating (3, 13). Sequence analysis of a 1,463-bp segment of the 16S rRNA genes of the organism demonstrated 99.2% identity with G. vaginalis ATCC 14018T (GenBank accession no. M58744) and clustering within GenBanks 16S sequences for G. vaginalis only. Antimicrobial susceptibilities were determined by broth microdilution using Sensititre GPN3F panels and cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth with lysed horse blood (2 to 5% [vol/ vol]) by Trek Diagnostics Inc. (Nova Century Scientic Inc., Burlington, Ontario, Canada), by using the manufacturers instructions and following CLSI guidelines for Streptococcus spp. other than S. pneumoniae (8). The MICs (in g/ml) observed were 0.25 for erythromycin, 0.12 for quinupristin-dalfopristin, 1.0 for vancomycin, 0.5 for ampicillin, 0.5 for rifampin, 0.12 for clindamycin, 0.5 for daptomycin, 2.0 for tetracycline, 1.0 for levooxacin, 0.5 for linezolid, 0.5 for penicillin, 2.0 for gentamicin, 1.0 for ciprooxacin, 1/19 for trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, 8.0 for ceftriaxone, and 1.0 for gatioxacin, consistent with previous ndings (6).

usually in men with identiable risk factors, including immunosuppression, anatomical genitourinary abnormalities, and alcoholism (2, 5, 10, 12, 15). Here we present the rst published case of G. vaginalis bacteremia in a previously healthy man with urolithiasis. Although the patients urine culture grew a potential uropathogen, it was present in 108 CFU/liter and was not identied in any of the blood cultures obtained, despite the patient not receiving antimicrobials at the time of culture. Furthermore, due to the lack of on-site microbiology facilities, 15 h elapsed from the time of specimen collection to its arrival at the microbiology laboratory, and for part of that period, refrigeration for storage of the urine was not available. Therefore, the isolation of E. coli from the urine specimen may have represented the overgrowth of a contaminant. Lastly, since two sets and three bottles of blood cultures were positive for G. vaginalis, but none were positive for E. coli, it is unlikely that E. coli played a role in his urosepsis. The treatment of G. vaginalis infections outside the female genital tract has not been studied. Previous case reports have documented successful therapy with -lactams, tetracyclines, cephalosporins, clindamycin, chloramphenicol, and metronidazole alone or in combination (2, 5, 10, 12, 15). Cases of severe sepsis have been treated with combination therapy (5, 12, 15). In our case, the removal of the stone and a short course of ciprooxacin therapy were curative. Virulence factors of G. vaginalis are not well characterized. The bacterium produces a hemolysin and a sialidase which play a role in the evasion of mucosal immunity and result in local tissue damage (7). Teichoic acid in the cell wall may produce a systemic inammatory response after invasion, but the factors that allow the organism to cause systemic infection are not known. However, a recent report of G. vaginalis bacteremia with multifocal abscess formation in an alcoholic patient who was otherwise immunocompetent suggests that the organism has some capacity to evade the immune response (5). In conclusion, we report the rst case of urolithiasis complicated by G. vaginalis bacteremia in an otherwise well male patient. The patient was successfully treated with stone extraction and a short course of ciprooxacin without adverse sequelae. This case illustrates that G. vaginalis may be an occasional cause of signicant systemic disease in both men and women and that the original smear, being read as a gramnegative coccobacillus, caused some delay in the diagnosis and correct identication of the pathogen. Nucleotide sequence accession number. A nearly full 16S sequence for the isolate studied here has been deposited under GenBank accession no. EF194095.

REFERENCES

Downloaded from http://jcm.asm.org/ on September 12, 2013 by guest

Gardnerella vaginalis is typically associated with bacterial vaginosis (6). It has also been reported as a pathogen in women following delivery or pelvic surgery, potentially leading to the preterm rupture of membranes, chorioamnionitis, and postpartum fever and to bacteremia in neonates (1, 11, 14). However, in one study, 7 to 11% of men had G. vaginalis as part of their urogenital or anorectal ora, leading to the possibility of urinary tract colonization and infection (9). In the present study, the patient had a sexual partner but the status regarding colonization or infection by this agent was not known. G. vaginalis bacteremia has rarely been described for men and

1. Agostini, A., M. Beerli, F. Franchi, F. Bretelle, and B. Blanc. 2003. Gardnerella vaginalis bacteremia after vaginal myomectomy. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 108:229. 2. Bastida Vila, M. T., P. Lopez Onrubia, J. Rovira Lledos, J. A. Martinez Martinez, and M. Exposito Aguilera. 1997. Gardnerella vaginalis bacteremia in an adult male. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 16:400401. 3. Bernard, K. A., M. Bellefeuille, and E. P. Ewan. 1991. Cellular fatty acid composition as an adjunct to the identication of asporogenous, aerobic gram-positive rods. J. Clin. Microbiol. 29:8389. 4. Bernard, K. A., C. Munro, D. Wiebe, and E. Ongsansoy. 2002. Characteristics of rare or recently described Corynebacterium species recovered from human clinical material in Canada. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:43754381. 5. Calvert, L. D., M. Collins, and J. R. Bateman. 2005. Multiple abscesses caused by Gardnerella vaginalis in an immunocompetent man. J. Infect. 51:E27E29.

806

CASE REPORTS

J. CLIN. MICROBIOL.

11. Florez, C., B. Muchada, M. C. Nogales, A. Aller, and E. Martin. 1994. Bacteremia due to Gardnerella vaginalis: report of two cases. Clin. Infect. Dis. 18:125. 12. Legrand, J. C., A. Alewaeters, L. Leenaerts, P. Gilbert, M. Labbe, and Y. Glupczynski. 1989. Gardnerella vaginalis bacteremia from pulmonary abscess in a male alcohol abuser. J. Clin. Microbiol. 27:11321134. 13. ODonnell, A. G., D. E. Minnikin, M. Goodfellow, and P. Piot. 1984. Fatty acid, polar lipid and wall amino acid composition of Gardnerella vaginalis. Arch. Microbiol. 138:6871. 14. Reimer, L. G., and L. B. Reller. 1984. Gardnerella vaginalis bacteremia: a review of thirty cases. Obstet. Gynecol. 64:170172. 15. Wilson, J. A., and A. J. Barratt. 1986. An unusual case of Gardnerella vaginalis septicaemia. Br. Med. J. 293:309.

6. Catlin, B. W. 1992. Gardnerella vaginalis: characteristics, clinical considerations, and controversies. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 5:213237. 7. Cauci, S., S. Driussi, R. Monte, P. Lanzafame, E. Pitzus, and F. Quadrifoglio. 1998. Immunoglobulin A response against Gardnerella vaginalis hemolysin and sialidase activity in bacterial vaginosis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 178:511515. 8. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2006. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically. Approved standard M7-A7, 7th ed. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. 9. Dawson, S. G., C. A. Ison, G. Csonka, and C. S. Easmon. 1982. Male carriage of Gardnerella vaginalis. Br. J. Vener. Dis. 58:243245. 10. Denoyel, G. A., E. B. Drouet, H. P. De Montclos, A. Schanen, and S. Michel. 1990. Gardnerella vaginalis bacteremia in a man with prostatic adenoma. J. Infect. Dis. 161:367368.

Downloaded from http://jcm.asm.org/ on September 12, 2013 by guest

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Brother Home LeafletDocument2 pagesBrother Home Leafletalf TantayNo ratings yet

- Swi20 000234Document1 pageSwi20 000234Muhamad AfidinNo ratings yet

- Guide To Complementary Feeding - WHODocument56 pagesGuide To Complementary Feeding - WHOFMDC100% (1)

- Sunnan Abu DawudDocument1,195 pagesSunnan Abu DawudMuhamad AfidinNo ratings yet

- EIJES6029Document8 pagesEIJES6029Md. Badrul IslamNo ratings yet

- Full Text 01Document54 pagesFull Text 01Muhamad AfidinNo ratings yet

- Bab I Manajemen LaboratoriumDocument10 pagesBab I Manajemen LaboratoriumMuhamad AfidinNo ratings yet

- 21518Document5 pages21518Muhamad AfidinNo ratings yet

- 01 Cover ConsumablesDocument23 pages01 Cover ConsumablesMuhamad AfidinNo ratings yet

- Determine Iron Concentration in Water Using SpectrophotometryDocument4 pagesDetermine Iron Concentration in Water Using SpectrophotometryLeah ArnaezNo ratings yet

- Iodine Titrimetry Vit CDocument6 pagesIodine Titrimetry Vit CMuhamad AfidinNo ratings yet

- Proceeding ISGH Update 12 OktoberDocument495 pagesProceeding ISGH Update 12 OktoberMuhamad AfidinNo ratings yet

- FL NUQVRFPTIz NZ Q2 LJ Aw My 4 W Mi 4 W NAADocument2 pagesFL NUQVRFPTIz NZ Q2 LJ Aw My 4 W Mi 4 W NAAMuhamad AfidinNo ratings yet

- FL NUQVRFPTIz NZ Q2 LJ Aw My 4 W Mi 4 W NAADocument2 pagesFL NUQVRFPTIz NZ Q2 LJ Aw My 4 W Mi 4 W NAAMuhamad AfidinNo ratings yet

- New Doc 3Document1 pageNew Doc 3Muhamad AfidinNo ratings yet

- Stok Bahan Kimia Lab KimiaDocument6 pagesStok Bahan Kimia Lab KimiaMuhamad AfidinNo ratings yet

- AAE Bahan AgusDocument22 pagesAAE Bahan AgusMuhamad AfidinNo ratings yet

- Buffer ProtocolDocument6 pagesBuffer ProtocolMandy MontgomeryNo ratings yet

- SS Agar PronadisaDocument2 pagesSS Agar PronadisaMuhamad AfidinNo ratings yet

- Ik HimediaDocument2 pagesIk HimediaMuhamad AfidinNo ratings yet

- Carbon Compounds and Chemical BondsDocument72 pagesCarbon Compounds and Chemical BondsMuhamad AfidinNo ratings yet

- Radiometer ABL 700 SerieDocument234 pagesRadiometer ABL 700 SerieMuhamad AfidinNo ratings yet

- BP BanDocument767 pagesBP BanMuhamad AfidinNo ratings yet

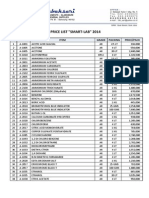

- Smart LabDocument4 pagesSmart LabMuhamad AfidinNo ratings yet

- Himark ManDocument4 pagesHimark ManMuhamad AfidinNo ratings yet

- HiMark Calculator V1Document4 pagesHiMark Calculator V1Muhamad AfidinNo ratings yet

- Plastic WareDocument6 pagesPlastic WareMuhamad AfidinNo ratings yet

- BP 00Document45 pagesBP 00Muhamad AfidinNo ratings yet

- Lab1ESR 08Document11 pagesLab1ESR 08Muhamad AfidinNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- IM Shelf - AmbossDocument61 pagesIM Shelf - AmbossHaadi AliNo ratings yet

- DHI Score PDFDocument2 pagesDHI Score PDFAnonymous HNGH1oNo ratings yet

- Baker v. Dalkon Sheild, 156 F.3d 248, 1st Cir. (1998)Document10 pagesBaker v. Dalkon Sheild, 156 F.3d 248, 1st Cir. (1998)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Prevalence of thyroid dysfunctionDocument32 pagesPrevalence of thyroid dysfunctiondalip kumarNo ratings yet

- EMS Drug DilutionDocument21 pagesEMS Drug Dilutionthompson godfreyNo ratings yet

- Denumire Comerciala DCI Forma Farmaceutica ConcentratieDocument4 pagesDenumire Comerciala DCI Forma Farmaceutica ConcentratieAlina CiugureanuNo ratings yet

- Vidas Troponin High Sensitive Ref#415386Document1 pageVidas Troponin High Sensitive Ref#415386Mike GesmundoNo ratings yet

- Standard Case Report Checklist and Template For AuthorsDocument5 pagesStandard Case Report Checklist and Template For AuthorsArief MunandharNo ratings yet

- 6th Grade (Level F) Spelling ListsDocument36 pages6th Grade (Level F) Spelling ListsArmaan100% (1)

- APTA Combined Sections Meeting 2008: Fugl-Meyer AssessmentDocument17 pagesAPTA Combined Sections Meeting 2008: Fugl-Meyer AssessmentDaniele Bertolo100% (1)

- Maths On The Move' - Effectiveness of Physically-Active Lessons For Learning Maths and Increasing Physical Activity in Primary School StudentsDocument22 pagesMaths On The Move' - Effectiveness of Physically-Active Lessons For Learning Maths and Increasing Physical Activity in Primary School Studentsiisu-cmse libraryNo ratings yet

- Daftar PustakaDocument6 pagesDaftar Pustakasatria divaNo ratings yet

- Retainer types and uses in orthodonticsDocument6 pagesRetainer types and uses in orthodonticsSahana RangarajanNo ratings yet

- Food and Exercise LogDocument24 pagesFood and Exercise LogmhetfieldNo ratings yet

- Victor Frankl & LogotherapyDocument5 pagesVictor Frankl & LogotherapyAlexandra Selejan100% (3)

- Gastroenterología y Hepatología: Scientific LettersDocument2 pagesGastroenterología y Hepatología: Scientific LettersAswin ArinataNo ratings yet

- Pharyngitis Laryngitis TonsillitisDocument10 pagesPharyngitis Laryngitis Tonsillitisapi-457923289No ratings yet

- Drug Study DengueDocument3 pagesDrug Study DengueiamELHIZANo ratings yet

- Ateneo de Zamboanga University Nursing Skills Output (NSO) Week BiopsyDocument4 pagesAteneo de Zamboanga University Nursing Skills Output (NSO) Week BiopsyHaifi HunNo ratings yet

- Narcotics and Antimigraine Agents (AE, Drug-Drug Interactions)Document5 pagesNarcotics and Antimigraine Agents (AE, Drug-Drug Interactions)ShiraishiNo ratings yet

- 1583 - Intermediate Grammar Test 22Document4 pages1583 - Intermediate Grammar Test 22SabinaNo ratings yet

- Overcoming Low Self-Esteem Extract PDFDocument40 pagesOvercoming Low Self-Esteem Extract PDFMarketing Research0% (1)

- Severe Gastric ImpactionDocument4 pagesSevere Gastric ImpactionNanda Ayu Cindy KashiwabaraNo ratings yet

- Gval ResumeDocument1 pageGval Resumeapi-403123903No ratings yet

- Tugas Bahasa Inggris Wound CareDocument2 pagesTugas Bahasa Inggris Wound CareBela Asa100% (1)

- Machine Learning Predicts 5-Chloro-1 - (2 - Phenylethyl) - 1h-Indole-2,3-Dione As A Drug Target For Fructose Bisphosphate Aldolase in Plasmodium FalciparumDocument7 pagesMachine Learning Predicts 5-Chloro-1 - (2 - Phenylethyl) - 1h-Indole-2,3-Dione As A Drug Target For Fructose Bisphosphate Aldolase in Plasmodium FalciparumInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- MidazolamDocument18 pagesMidazolamHarnugrahanto AankNo ratings yet

- 0nvkwxysn505jodxuxkr5z3v PDFDocument2 pages0nvkwxysn505jodxuxkr5z3v PDFAnjali Thomas50% (2)

- PHN Health TeachingDocument3 pagesPHN Health TeachingJeyser T. GamutiaNo ratings yet

- Unit 5 Hospital EquipmentDocument3 pagesUnit 5 Hospital EquipmentALIFIANo ratings yet