Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Eng 000-01 Course Design

Uploaded by

api-242501189Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Eng 000-01 Course Design

Uploaded by

api-242501189Copyright:

Available Formats

Course Design: ENG 000-01 Composing Rhetoric Catalogue Description: ENG 000 Composing Rhetoric.

. (3) Development of skills in writing transfer through awareness and analysis, using the evolution of rhetorical voice as an organizing principle.

Theoretical Perspective: If rhetoric is communication that seeks to persuade or create change (Smith 1), then composing rhetoric is writing which demonstrably impacts the thinking and/or behavior of the reader. From providing additional insight into the understanding of a poem to encouraging people to make different personal choices, and from advancing a theoretical argument to calling for sweeping policy changes, rhetoric espouses a point of view and exists for a specific purpose. Composition (the act of composing) is, at its simplest, just writing. Yet, composing, it could be said, involves writing as a deliberate craft; its advancement involves reconstruction of what we already know rather than simply reusing previously acquired skills (Nowacek 25).

What does it mean, you may ask, to study the composition of rhetoric? It is to examine closely the way that written rhetoric is developed, and to practice through writing and revision and rewriting the deliberate craft of it. Just as the conscious development and employment of rhetoric allows for the deconstruction and recontextualization of rhetorical methods (Rounsaville 7), so then might we consciously parse writing technique. Study involves a close reading of theoretical texts (in this course, from the field of writing studies) as well as the dissection and understanding of how professional writers have employed composed rhetoric in their work.

This cued, reflective process while still relatively new as a tool for teaching writing is designed to build a range of skills useful in both your academic career and in the writing you do outside of or after it. It is a major component of your preparation to adapt to existing society and to participate in [its] transformation (Beach 57). Moving from a gate-keeping to a gateopening function (Rounsaville 1), this alternate method of teaching is based on what you could metaphorically describe as weaving compositional rhetoric from the fiber rather than fabric level. It is designed to enable successful acquisition, or learned recognition of significance (Bawarshi 653) in the study of writing, even if a current context may have little or no surface resemblance to prior or presumed future writing experiences.

Course Objectives: Successful engagement in this course and thorough completion of its assignments will result in a heightened awareness of how written rhetoric is crafted. Students will be able to (1) identify rhetorical situations and writing genres they have encountered prior to this course; (2) articulate differences and similarities between those situations/genres and the ones they are asked to negotiate this semester; (3) revise and improve previous writing assignments using new understandings of what it means to compose rhetoric; (4) analyze an assigned reading in rhetoric by examining the methods and strategic choices made by its author; and (5) write two distinct rhetorical papers, successfully employing a recontextualized and enhanced understanding of the writing and revision process required for the composition of rhetoric. In addition to these major papers, other assignments will encourage reflection and analysis of rhetorical writing of the students own work and that of their classmates, as well as the work of writing professionals. Class time will be used for a mix of discussion and brief

lecture, with significant time also devoted to small-group analysis using workshop techniques. Students will also meet one-on-one with the instructor at least once during the writing process for each of the two major papers.

Required Texts and Reading Assignments: Reading for this course will vary widely, with a mix of texts that include mechanics, theory, research, popular science, and memoir. Revising Prose (Richard A. Lanham) Rhetoric and Human Consciousness: a History (Craig R. Smith) Naming Nature: the Clash Between Instinct and Science (Carol Kaesuk Yoon) Life Notes: Personal Writings by Contemporary Black Women (Patricia Bell-Scott, Ed.) Outrageous Acts and Everyday Rebellions (Gloria Steinem) Supplemental readings provided on CD: Reiff, Mary Jo, and Anis Bawarshi. Tracing Discursive Resources: How Students Use Prior Genre Knowledge to Negotiate New Writing Contexts in First-Year Composition. Written Communication 28:3 (2011). Rounsaville, Angela. Selecting Genres for Transfer: The Role of Uptake in Students Antecedent Genre Knowledge Composition Forum 26 (Fall 2012).

Writing Assignments: This course will be writing intensive, but the intensity referenced here is an intensity of focus rather than intensity of volume. You may or may not write more than you do in other courses focused on writing, but you will be asked to write more deliberately. You will also be asked to analyze how other writers compose their rhetoric.

(1) Analysis of Recycled Work Choose a persuasive or argumentative paper you have written from a previous course, complete with notes or marked-up copy from the

instructor. Analyze your use of rhetoric in this prior assignment, engaging the definitions encountered in assigned readings and answering the following questions: What were the rhetorical points you tried to make here? Which parts of the paper succeeded? Failed? How can this paper be improved, making it a more successful rhetorical work? Also, engage with the notes or critiques from your instructor on the graded paper: How do these remarks change the way you now view what you originally wrote? Do you agree or disagree with those assessment, and why? Describe your writing process for putting this paper together.

(2) Revision/Expansion of Recycled Work Based on your analysis of that recycled paper and on what you have learned thus far in the semester, revise and/or expand your paper from the initial Recycled Work assignment. Along with the new version of the paper, attach your notes from the revision process, explaining your rationale for the changes or reworking of the text. Make specific references throughout the paper to assigned readings and/or class discussions that have influenced your work during the revision process. If you take this project to the Writing Center for assistance (which I strongly recommend), please keep your notes and draft from that experience to hand in as well.

(3) Analysis of Assigned Rhetorical Readings Chose one work from the list of assigned rhetorical readings, and discuss the writers methods and level of success. Engage fully with the text in ways that include your observations about the format and structure of the piece, as well as issues of style and word choice. What have these choices allowed the writer to do? How has the writer crafted a rhetorical argument or persuasive piece?

Which strategies worked the best? The least? Again, I strongly encourage you to make use of the services available to you in the Writing Center, and that you retain and submit your notes and draft from any session(s) there.

(4) Making Your Case: Social Justice After selecting a topic related to a political or social issue, write a rhetorical paper that advances your argument(s) regarding some aspect of social justice. What policy or cultural changes can impact this particular issue? Keep in mind the rhetorical responsibility to persuade others to your point of view, and/or to persuade them to act or change in some way. Consider your strategies as you compose this rhetoric. Cite credible experts scholars, researchers, writers and sources such as professional and academic journals to aid in making your case.

(5) Making Your Case: In the Academy Develop a rhetorical paper that makes a particular and insightful academic argument in your major discipline (or a related one) or in the field of writing studies. Persuade your reader to draw the connections and comparisons central to your argument, push them to re-examine what they may believe or think about this subject, and carefully craft your rhetorical strategy to accomplish this end. Again, cite credible experts scholars, researchers, writers and sources such as professional and academic journals to aid in bolstering your argument. I encourage you to think of this assignment as a piece to submit for a conference presentation or for journal publication and then to actually submit it. Writing this paper for a specific purpose instead of just a grade is one of the best ways to ensure that you do the kind of work that earns an A.

(6) Journaling Set up a GoogleDoc for use as your on-line journal, and share that document with me. Over the course of the semester, use your journal for recording and analyzing the substance and application of what you are learning. Minimum required entries must engage and reflect on your writing process, including separate entries related to each of the writing assignments (1-5) as well as two or more entries engaging additional assigned rhetorical readings.

Works Cited Bawarshi, Anis. Taking Up Language Differences in Composition College English 68:6 (2006). Beach, King. Consequential Transitions: A Developmental View of Knowledge Propagation Through Social Organizations. Between School and Work; New Perspectives on Transfer and Boundary-Crossing. Ed. Terrtu Tuomi-Grohn and Yrjo Engestrom. Amsterdam: Emerald Group, 2003. Bergmann, Linda S., and Janet Zepernick. Disciplinarity and Transfer: Students Perceptions of Learning to Write. WPA: Writing Program Administration 31:1-2 (Fall/Winter 2007). Brent, Doug. Transfer, Transformation, and Rhetorical Knowledge: Insights from Transfer Theory. Journal of Business and Technical Communication 25:4 (2011). Driscoll, Dana Lynn. Connected, Disconnected, or Uncertain: Student attitudes about Future Writing Contexts and Perceptions of Transfer from First Year Writing to the Disciplines. Across the Disciplines: A Journal of Language, Learning, and Academic Writing 8:2 (Dec 2011). Nowacek, Rebecca. Agents of Integration: Understanding Transfer as a Rhetorical Act. Carbondale: Southern Illinois, 2011. Print. Perkins, D.N., and Gavriel Salomon. Are Cognitive Skills Context-Bound? Educational Researcher 18:16 (1989). Reiff, Mary Jo, and Anis Bawarshi. Tracing Discursive Resources: How Students Use Prior Genre Knowledge to Negotiate New Writing Contexts in First-Year Composition. Written Communication 28:3 (2011). Rounsaville, Angela. Selecting Genres for Transfer: The Role of Uptake in Students Antecedent Genre Knowledge Composition Forum 26 (Fall 2012). Smith, Craig R. Rhetoric and Human Consciousness: a history. 3rd Ed. Long Grove: Waveland, 2009. Print. Wardle, Elizabeth. Mutt Genres and the Goal of FYC: Can We Help Students Write the Genres of the University? College Composition and Communication 60:4 (June 2009).

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (589)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5796)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Harpur Jazz EnsembleDocument34 pagesThe Harpur Jazz EnsembleJoey LieberNo ratings yet

- GROUP 6 HUMSS A DISIPLINA Research PaperDocument20 pagesGROUP 6 HUMSS A DISIPLINA Research PaperNathalie Uba100% (1)

- Defining-the-Gravamen-the-Bar-Reform-Movement PDFDocument37 pagesDefining-the-Gravamen-the-Bar-Reform-Movement PDFRuby SantillanaNo ratings yet

- ACTION PLAN in Guidance & CounselingDocument2 pagesACTION PLAN in Guidance & Counselingmichelle c lacad100% (6)

- Bsed Eng Sy 2020 2021 Thesis Titles Rosemarie Castillo With Cla Comments 04.14.2021Document10 pagesBsed Eng Sy 2020 2021 Thesis Titles Rosemarie Castillo With Cla Comments 04.14.2021Nicole R. IlaganNo ratings yet

- Learners Progress Report Card For The New Normal S.Y. 2021 - 2022Document4 pagesLearners Progress Report Card For The New Normal S.Y. 2021 - 2022Jessel Galicia100% (1)

- Field Study 1 - Learning Episode 4Document14 pagesField Study 1 - Learning Episode 4Lara Mae BernalesNo ratings yet

- Daftar Pustaka. Per 1 JUNI 2016Document8 pagesDaftar Pustaka. Per 1 JUNI 2016alhanunNo ratings yet

- 44 Co Education Is Good or Bad (Short Essay) - The College StudyDocument4 pages44 Co Education Is Good or Bad (Short Essay) - The College StudyAmirhamayun KhanNo ratings yet

- Final Annual Result Prize Distribution 2019/20: Staff Members LSD WingDocument2 pagesFinal Annual Result Prize Distribution 2019/20: Staff Members LSD WingSadaf RizwanhumayoonNo ratings yet

- Kumilos Worksheet 1Document8 pagesKumilos Worksheet 1analyn a. amoncioNo ratings yet

- Leah Simi ResumeDocument6 pagesLeah Simi Resumeapi-238156798No ratings yet

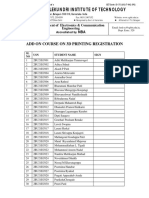

- Add On Course On 3d Printing RegistrationDocument2 pagesAdd On Course On 3d Printing RegistrationLohit DalalNo ratings yet

- June 2005 MS - Paper 2 CIE Physics IGCSEDocument7 pagesJune 2005 MS - Paper 2 CIE Physics IGCSEShivraj NaikNo ratings yet

- HKDSE Math Comp PP 20120116 EngDocument39 pagesHKDSE Math Comp PP 20120116 EngLam LamlamNo ratings yet

- School Handbook 13-14 in PDFDocument43 pagesSchool Handbook 13-14 in PDFElla ToonNo ratings yet

- Kent State Geauga Campus Economic ImpactDocument40 pagesKent State Geauga Campus Economic Impactlkessel5622No ratings yet

- Mapeh MusicDocument5 pagesMapeh Musicjodzmary860% (1)

- Mba MeritDocument233 pagesMba Meritashish chudasamaNo ratings yet

- 879Document255 pages879Pinki raniNo ratings yet

- Final Draft 2019 Application Guidelines For Auto and Dereg As of Dec 13 2018Document16 pagesFinal Draft 2019 Application Guidelines For Auto and Dereg As of Dec 13 2018DonnaNo ratings yet

- The ProblemDocument26 pagesThe ProblemNizelle Amaranto ArevaloNo ratings yet

- WH QuestionsDocument7 pagesWH Questionswulandari wasioNo ratings yet

- The Dark Side of Zero Tolerance - Can Punishment Lead To Safe SchoolsDocument11 pagesThe Dark Side of Zero Tolerance - Can Punishment Lead To Safe SchoolsAylinNo ratings yet

- Meditation For Law Students: Mindfulness Practice As Experiential LearningDocument13 pagesMeditation For Law Students: Mindfulness Practice As Experiential LearningRhege AlvarezNo ratings yet

- Friday Report June 6, 2014Document6 pagesFriday Report June 6, 2014Rodman ReynoldsNo ratings yet

- Lp2 EED8Document19 pagesLp2 EED8Ronalyn DadaleNo ratings yet

- DY Patil Bokaro PresentationDocument7 pagesDY Patil Bokaro PresentationArun KumarNo ratings yet

- Standards Based Grading Insights From TeachersDocument8 pagesStandards Based Grading Insights From Teachersapi-232886317No ratings yet

- Admission Guidelines 2021-22Document20 pagesAdmission Guidelines 2021-22KeralagoldNo ratings yet