Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Elena Filipovic What Is An Exhibition

Elena Filipovic What Is An Exhibition

Uploaded by

felipepenaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Elena Filipovic What Is An Exhibition

Elena Filipovic What Is An Exhibition

Uploaded by

felipepenaCopyright:

Available Formats

6

/

10

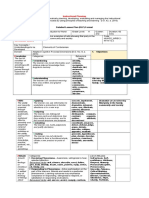

What Is an Exhibition?

Elena Filipovic

Ten Fundamental

Questions of

Curating

WHAT IS AN EXHIBITION? 3 TEN FUNDAMENTAL QUESTIONS OF CURATING

Ten Fundamental Questions

of Curating

Publishing director

Edoardo Bonaspetti

Editor

Jens Hoffmann

Copy editor

Lindsey Westbrook

A project realized in partnership with

Artistic director

Milovan Farronato

Design

Studio Mousse

Issue #6

Why Mediate Art?

by Elena Filipovic,

visual concept Nairy Baghramian

based on Palermo's wall drawings

Ten Fundamental Questions

of Curating

is printed in Italy and published

five times a year by

Mousse Publishing

Publisher

Contrappunto S.R.L.

via Arena 23

20123, Milan - Italy

What is an exhibition? Artists have been aware of the implications

of the question for a long time. Gustave Courbets 1855 rogue pavil-

ion (across the way from the ofcial Salon), featuring a self-fnanced

presentation of his own paintings, was perhaps the frst and most

dramatic indication of artists desires to reimagine the way institu-

tions organized and displayed their work. And from some of the ear-

liest avant-gardes (Constructivists, Dadaists, Surrealists) to the pre-

sent, artists have been the most active instigators of critical responses

to, and reinventions of, the exhibition as a form.

1

Text Elena Filipovic

Floorplan Nairy Baghramian

What Is an Exhibition?

WHAT IS AN EXHINIION? 101 100 TEN FUNDAMENTAL QUESTIONS OF CURATING

Tink of Richard Hamilton and Victor Pasmores 1957 exhibition,

bluntly titled An Exhibit, which had no images and no subject, no

theme other than itself; it was self-referential,

2

thus making the

display of display both its content and driving methodology. Or of

Graciela Carnevales 1968 exhibition in Buenos Aires: at the height

of the Argentine military dictatorship, she locked up guests at the

opening who only realized aferwards that their sequestration in the

empty exhibition space (and the resultant confusion, fear, paranoia,

and eventual escape) was the exhibition. Or of Martha Roslers 1989

If You Lived Here. . ., an exhibition series that refused to be the solo

show requested by the institution, and instead ofered a makeshif,

disorderly mix of art and nonart items related to housing injustic-

es in New York City that delivered an implicit critique of the host

institution. Or of Felix Gonzalez-Torress 1991 Every Week Tere Is

Something Diferent, set against a backdrop of seismic shifs in re-

cent American history (who could ignore, for instance, that the frst

Gulf War was at that very moment changing the rules of politics and

war weekly, if not daily?), and ofering a checklist and arrangement

that the artist changed each week, so that the exhibition was not a

singular constellation of artworks or single, consistent message, but

instead several constellations, each revealing how one object put next

to another could provoke diferent readings of both. Or even of Da-

vid Hammonss unannounced 1995 exhibition at a shop for African

objects, in which items made by the artist and the regular wares of

the shop were mixed with little indication of their difering status

through presentation or price. Tese are just a few examples among

many.

6 WHAT IS AN EXHIBITION?

Each artists approach was diferent. But long before the advent of

that professional speciesthe curatorand not letting up in the face

of its spectacular rise, each found a way to lay bare and counter some

of the implicit and most stalwart expectations of the exhibition as

such. Teir example makes it apparent that this seemingly simple

questionWhat is an exhibition?should be asked, all the better

to interrogate the premises that quietly support and perpetuate the

most conventional notions of the exhibition.

Te critical consensus today would seem to be that an exhibition

from its 15th-century roots in legal terminology as the displaying of

evidenceis, in the most basic terms, an organized presentation of a

selection of items to a public.

3

Simple enough. And reductive enough,

103 TEN FUNDAMENTAL QUESTIONS OF CURATING

even presuming that the presentation can be physical or virtual,

real or projected; the items either spectacular or discursive, mate-

rial or immaterial; and the public either known or unknown, com-

posed of one or many. But if the roots in legalese suggest that what is

held up for view aims to convince and demonstrate like evidence in a

court of law, resulting in exhibitions organized to speak conclusively,

authoritatively, and absolutely, then the tacit understanding of the

exhibition seems problematic.

What exactly are we viewing, as spectators, or contributing to, as art-

ists, or organizing, as curators? No theater of proofs, the exhibition

should be a performance of another sort. Of course, it can be many

things, but perhaps frst and foremost, it is not a neutral thing. In

its many lives, it has been understood as a scrim on which ideology

is projected, a machine for the manufacture of meaning, a theater

of bourgeois culture, a site for the disciplining of citizen-subjects,

or a mise-en-scne of unquestioned values (linear time, teleologi-

cal history, master narratives).

4

Political powers and the institutions

they support may long have been invested in making the exhibition

each of those things at diferent moments in history. But if we adopt

instead the model of the exhibition that artists have at times called

forcritical, oppositional, irreverent, provisional, questioningthe

term might be understood in an altogether diferent way.

Te exhibition? A single category term speaks for what can have such

wildly diferent aims and ambitions, with vast intellectual, aesthet-

ic, and ideological, not to mention geographic, economic, or insti-

tutional, diferences between its organizing bodies. Retrospective,

monographic, survey, group, biennial, triennial: each denotes a vari-

ant in the category. To say nothing about the fact that the tenor of the

result can be alternately overwrought, spectacular, modest, sensitive,

eloquent, transgressive the list can go on and on. All equally merit

8 9 TEN FUNDAMENTAL QUESTIONS OF CURATING

the term exhibition. Implicit in the question is thus not so much

what the meaning of the exhibition is as a category/genre/object, but

what it does, which is to say, how exhibitions function and matter,

and how they participate in the construction and administration of

the experience of the items they present.

It goes without saying that, without artists and artworks, the exhibi-

tions of the sort we are discussing would not be possible (and cura-

tors would be, quite simply, out of a job). Artworks are the essential

fulcrum around which both exhibition and curator turn. Still, an ex-

hibition is more than the series of artworks produced by a list of art-

ists, occupying a given space and hung more or less high on a wall.

And no matter how vital ideas may be to its preparation, conception,

or thematization, an exhibition is not a merely transparent represen-

tation of ideas (or ideology or politics) in space. Organize the very

same artworks in the very same space diferently, give the exhibition

a new title, and you can potentially elicit an entirely diferent expe-

rience or reading of the contents. Tis suggests that an exhibition

isnt only the sum of its artworks, but also the relationships created

between them, the dramaturgy around them, and the discourse that

frames them.

Can it be argued, then, that what a particular exhibition is lies as

much in its contents as in its method and form? And, further, that

one cannot actually separate any of those elements as if one were

WHAT IS AN EXHIBITION?

11 10 TEN FUNDAMENTAL QUESTIONS OF CURATING WHAT IS AN EXHIBITION?

not part of the other in the construction of an exhibition? In other

words, that there can be no such thing as contents (artworks) par-

ticipating in a show which are not concerned, in the very moment of

being exhibited and for as long as they are exhibited, by what brings

them together and what company they fnd themselves in? Tis is

not to say that the presentation is the message or context is content.

And make no mistake: Tis is no plea for the status of the curator as

an artist or for the curatorial conceit to itself approach the status of

quasi-artwork.

5

What is at stake is an ethics of curating, a responsi-

bility towards the very methodology that constitutes the practice.

6

Tat responsibility is also the responsibility to attend to artworks in a

way that is adequate to the risks that they take.

7

I have seen this done

before. Te exhibitions, whether organized by an artist or a profes-

sional curator, Ive admired most and have found most engaging and

thought provoking, seem to have developed their methodology and

form from the material intelligence and risk of the artworks brought

together. In these, the artwork was generative of the exhibition itself.

You might then say that an exhibition is the form of its arguments

and the way that its method, in the process of constituting the exhibi-

tion, lays bare the premises that underwrite the forming of judgment,

the conditioning of perception, and the construction of history. It is

the thinking and the debate it incites. It is also the trajectory of intel-

lectual and aesthetic investments that build up to it, for artist and

curator alike. But most importantly, it is the way in which its very

premises, classifcatory systems, logic, and structure can, in the very

moment of becoming an exhibition, be unhinged by the artworks

in it. If artworks are simultaneously the elements in an exhibitions

construction of meaning while being, dialectally, subjected to its

staging, they can also at moments articulate aesthetic and intellec-

tual positions or defne modes of engagement that transcend or even

defy their thematic or structural exhibition frames.

8

Te artwork can,

13 12 TEN FUNDAMENTAL QUESTIONS OF CURATING WHAT IS AN EXHIBITION?

in short, resist the very exhibition that purports to hold it neatly in

place. Tat is the idea of the work of art to which I would like to sub-

scribe.

Tat said, we have all witnessed the scene: an exhibition whose heavy-

handed curatorial premise and lack of sensitivity instrumentalizes

the artworks it presents. Such an exhibition may leave even a great

artwork little possibility to articulate itself against its contextal-

though Id like to think that the force of the artwork can still unsettle

what the curator says he or she is showing or doing in the exhibition.

Much better, of course, is when the curator doesnt seek to illustrate

curatorial ideas with artworks (as if exhibition-making were like lin-

ing up docile ducks in a row), but instead allows the particular recal-

citrance of the artwork to be a model for thinking what the exhibi-

tion could be. Either way, because the exhibition is a temporary state

of afairs, its framing of the work of artwhether done sensitively

or badlyis, by defnition, feeting. One might even say that if it can

last indefnitely, it is simply not an exhibition. Te frozen immobil-

ity of Donald Judds Marfa, Texas, compound is not an exhibition,

I would argue, but a shrine, a temple, a permanent collectionand

that notwithstanding the fact that the contents are displayed for view,

that Judd himself conceived their presentation as the ideal and ul-

timate public presentation of a specifc grouping of works, and not

notwithstanding whatever other exhibition-like qualities it might be

said to have. For there is an immutability and conclusiveness in a

presentation conceived with no end in sight that is contrary to what

an exhibition is.

14 WHAT IS AN EXHIBITION? 14 15 TEN FUNDAMENTAL QUESTIONS OF CURATING

Te ephemerality and lack of absoluteness of an exhibition might be

its most important features. Against the model of the exhibition as

the display of some indelible proof, one might admit how subjec-

tive an enterprise it is, and inevitably so. I cant help thinking here of

Writing Degree Zero, Roland Barthess response to Jean-Paul Sartres

claim that all texts involve the mutual exchange of responsibility be-

tween reader and writer (incidentally, the latter were gathered in a

publication titled with the question What Is Literature?). Barthes is

in partial agreement with Sartre but he argues that how a text is writ-

tenits formis as important to the politics of its exchange as what

the text says. And, he insists, one cannot escape from the fact that

there is a form. Even the kind of writing that attempts to achieve the

appearance of neutrality, a zero degree of style, denying that it even

17 16 TEN FUNDAMENTAL QUESTIONS OF CURATING WHAT IS AN EXHIBITION?

has a form, in fact has one.

9

As with writing, so it is with exhibition

making, with some curators and art institutions invested in the ap-

pearance of a zero degree of the exhibition and the pretense that the

artwork selection, organization, dramaturgy, and discursive frame-

work could not have been otherwise, as if their choices represent the

unfappable truth of History, instead of one possible reading among

many. Tat is how dominant ideas, positions, and values solidify and

get perpetuated.

But what if we thought of the exhibition as the site where deeply-

entrenched ideas and forms can come undone, where the ground on

which we stand is rendered unstable? Instead of the production of

knowledge so frequently cited in institutional statements of purpose,

an exhibition might provoke feelings of irreverence or doubt, or an

experience that is at once emotional, sensual, political, and intellec-

tual while being decidedly not predetermined, scripted, or directed

by the curator or the institution. In my experience, the artwork can

change (and ofen does change) what I think I know, and an exhibi-

tion is at its best when its curator can admit that. Celebrated here,

then, is the exhibition as a place for engagement, impassioned think-

19 18 TEN FUNDAMENTAL QUESTIONS OF CURATING WHAT IS AN EXHIBITION?

ing, and visceral experience (and of course even pleasure, as Dieter

Roelstraete so vociferously called for in an earlier installment of this

series), but not necessarily as the platform for the sort of empirical

knowing that we have all too ofen been led to believe is important

to the artwork and the exhibition alike.

10

As Susan Sontag explains:

A work of art encountered as a work of art is an experience,

not a statement or an answer to a question. Art is not only

about something; it is something. A work of art is a thing in

the world, not just a text or commentary on the world. . . .

[Artworks] present information and evaluations. But their

distinctive feature is that they give rise not to conceptual

knowledge (which is the distinctive feature of discursive or

scientifc knowledgee.g., philosophy, sociology, psychol-

ogy, history) but to something like an excitation, a phe-

nomenon of commitment, judgment in a state of thralldom

or captivation. Which is to say that the knowledge we gain

through art is an experience of the form or style of knowing

something, rather than knowledge of something (like a fact

or a moral judgment) in itself.

11

21 TEN FUNDAMENTAL QUESTIONS OF CURATING WHAT IS AN EXHIBITION? 20

Te defense of the particular excitation Sontag speaks about could

be the intangible contract the exhibition ofers both to visitors and

artists. It cannot, in that case, attempt to educate and prove the an-

swer, but might instead encourage unconventional ways of look-

ing at and reading the artwork (and then the world). Te follow-

ing may perhaps serve as an example. Collected in the pages of his

book, Inside the White Cube, is Brian ODohertys description of a

major Claude Monet exhibition held at the Museum of Modern Art

in New York in 1960. In ODohertys telling, the exhibitions curator,

William Seitz, had decided to take the frames of the paintings. He

hung the works, frameless, on the gallery walls; sometimes he even

inset the canvases to make them fush with the wall itself. In a single

gesture, Seitz showed Monets paintings to be something other than

portable commodities used to elegantly line bourgeois homes, some-

thing other than polite renditions of water lilies in dappled light. In

their stead, Seitz stressed what he saw as their implicit fatness and

doubts about the limiting edge (as ODoherty so keenly observes).

12

Seitz advanced a reading of Monets particular brand of modernity

and presented it so that viewers could confront the artists oeuvre as

23 22 TEN FUNDAMENTAL QUESTIONS OF CURATING WHAT IS AN EXHIBITION? TEN FUNDAMENTAL QUESTIONS OF CURATING

they never had before. It seems to have riveted the young artists who

saw it, not surprisingly, since they were at that moment grappling

precisely with questions of illusionism, edge, and the relationship of

easel painting to the wall.

Reading about that show as a curator just starting out, I recall being

in turns impressed and slightly disturbed by the audacity of Seitzs

curating. What if he had been wrong? I remember thinking to my-

self. Tat was before I had realized that it isnt (or at least shouldnt

be) a question of right or wrong, of proving something to be true or

not. To propose a reading of an artwork is diferent than to claim

to know what that artwork ultimately or defnitely means; the art-

work, afer all, is not an algebraic exercise with a single given answer,

determined by the set of equivalencies between a certain form and

a certain meaning. In other words, the exhibition need not be the

22 23

25 24 TEN FUNDAMENTAL QUESTIONS OF CURATING WHAT IS AN EXHIBITION? 24 WHAT IS AN EXHIBITION? 25 TEN FUNDAMENTAL QUESTIONS OF CURATING

place for an empirical object lesson, but instead the place for us to

take the risk of reading an artwork against the grain of its already ac-

cepted historical meanings. In understanding this, I remember also

understanding that, somehow, an exhibition is always made (perhaps

can only be made) from the vantage point of the moment in which

it fnds itself (and Seitzs moment was one of Color Field painting,

Clement Greenberg, a young Frank Stella, and, of course, the dis-

course on fatness). Tis realization underscored the fact that an ex-

hibition, no matter what else it is, is not abstract or ahistorical, but a

concrete situation located in a particular place and time.

At their best, exhibitions venture out on a limb, allowing all of the

strange and wondrous incommensurability of the artwork to pro-

voke its own terms of engagement. Such an endeavor could only be

subjective in the extreme, and, as a result, fallible, inexhaustive, po-

tentially contradictory, and provisionalall things that some of the

best exhibitions in my memory have dared to be. Te task, I think,

is to celebrate an exhibition-making in which the immediacy and

persistent intelligence of an artwork (and, through it, its particular

27 26 TEN FUNDAMENTAL QUESTIONS OF CURATING WHAT IS AN EXHIBITION?

way of responding to the world) might lead to the construction of

exhibitions that could ofer themselves as a counterproposal, an idyll,

an antidote of sorts to everything else (the media, the market, the

culture industry, History . . .) that claims to know what the right

art and narratives are at any given moment. An exhibition should

strive, instead, to operate according to a counter authoritative logic

and, in so doing, become a crucible for transformative experience

and thinking.

What is to be done, then, with what Documenta artistic director

Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev recently referred to as this obsolete

twentieth-century object, the exhibition?

13

We can, of course, re-

main mortgaged to the idea that the exhibition cannot be other than

what it has already conventionally been or what some so doggedly

want it to be, in which case it might indeed be obsolete as a valid en-

terprise. Or we could lobby for it to be what exceptional examples in

the recent and distant past have already pointed to. In that case, there

is no reason the questionWhat is an exhibition?should ever lose

its relevance. It should probably be asked at regular intervals, again

and again, lest we forget that the exhibition must not become calci-

fed into an inviolable or unquestionable edifce.

29 28 TEN FUNDAMENTAL QUESTIONS OF CURATING WHAT IS AN EXHIBITION?

Notes

1. Art history has been exceedingly slow to

account for the importance of the exhibi-

tion as a cultural form. And if it seems vital

that we fnally take adequate account of the

history of exhibitions, the goal is less about

simply creating a new object for art history,

and more about undertaking real discus-

sions about the role and repercussions of

the exhibition. See Bruce Altschulers Te

Avant Garde in Exhibition: New Art in the

20th Century (New York: Harry N. Abrams,

1994) and From Salon to Biennial: Exhibi-

tions that Made Art History, vol. 1, 1863

1959 (New York and London: Phaidon

Press, 2008).

2. Pop Daddy: An Interview with Richard

Hamilton by Hans Ulrich Obrist, Tate

Magazine no. 4 (MarchApril 2003): http://

www.tate.org.uk/magazine/issue4/pop-

daddy.htm.

3. Tis paraphrased defnition approaches

the way Wikipedia and most dictionaries

defne the term.

4. See Donald Preziosi, Te Brain of the

Earths Body: Art, Museums, and the Phan-

tasms of Modernity (Minnesota: University

of Minnesota Press, 2003) and Tony Ben-

nett, Te Birth of the Museum: History,

Teory, Politics (London: Routledge, 1995).

5. Te understanding of the artwork, artist,

and curator that this essay is founded on

could not be further from the idea that the

curator is a producer or coproducer of the

artwork itself, as argued for in numerous

essays by theorists and curators, including

Boris Groys, Multiple Authorship, in Te

Manifesta Decade: Debates on Contempo-

rary Art Exhibitions and Biennials in Post-

Wall Europe, eds. Barbara Vanderlinden

and Elena Filipovic (Cambridge, Mas-

sachusetts: MIT Press, 2005), 93-100; or,

more recently, John Roberts, Te Curator

as Producer: Aesthetic Reason, Nonaesthet-

ic Reason, and Infnite Ideation, Manifesta

Journal no. 10 (200910): 5159.

6. Te conception of the exhibition that this

essay pleads for is diametrically opposed

to the idea of the artwork as impotent and

in need of being cured by the curator.

See the following essays by Boris Groys:

Politics of Installation, e-fux journal no.

2 (January 2009), http://www.e-fux.com/

journal/view/31; Curator as Iconoclast,

History and Teory, Bezalel no. 2, www.

scribd.com/doc/47605999/Boris-Groys-

Te-Curator-as-Iconoclast; and On the

Curatorship, Art Power(Cambridge, Mas-

sachusetts: MIT Press, 2008), 4352. All

of these contain a variant on the following

statement: In its origin, it seems, the work

of art is sick, helpless; in order to see it,

viewers must be brought to it as visitors are

brought to a bed-ridden patient by hospital

staf. It is in fact no coincidence that the

word curator is etymologically related to

cure. Curating is curing. Te process of

curating cures the images powerlessness,

its incapacity to present itself. Te artwork

needs external help, it needs the exhibi-

tion and the curator to become visible.

Te medicine that makes the image appear

healthythat makes the image literally

appear, and do so in the best lightis the

exhibition.

7. Afer struggling for the words to describe

this responsibility, I encountered the notion

in Briony Fers brilliant Eva Hesse: Studio

Work (New Haven: Yale University Press,

2010). Tere she speaks directly to the role

of the art historian attending to artworks

in ways appropriate to the risks they take,

but this idea matters just as powerfully for

the curator of an exhibition. I have bor-

rowed her beautiful formulation here.

8. Tis has always seemed the force of exhi-

bitions as cultural objects and what utterly

separates them from, say, illustrated essays,

which might on the surface seem like an

appropriate comparison. Afer all, illus-

trated essays (or even an art historians slide

lecture) create juxtapositions, compari-

sons, and relationships between (images

of) artworks accompanied by theoretical

arguments (maybe even the same ones

that might be expressed in an exhibition

catalogue or press release), but both lack

the material confrontation with the artwork

itself, which can refuse the very conven-

tions that purport to hold it in place.

9. Roland Barthes, Writing Degree Zero,

trans. Annette Lavers and Colin Smith

(New York: Hill and Wang, 1977).

10. Dieter Roelstraete, How About Pleas-

ure?, in the second volume published in

the series Ten Fundamental Questions of

Curating.

11. Susan Sontag, On Style, in Against In-

terpretation (New York: Picador, 2001), 21.

12. Description detailed in Brian

ODoherty, Inside the White Cube: Te Ide-

ology of the Gallery Space (Berkeley and Los

Angeles: UC Press, 1999), 25: Impression-

ist pictures which assert their fatness and

their doubts about the limiting edge are

still sealed of in Beaux-arts frames that do

little more than announce Old Master- and

monetary-status. When William C. Seitz

took of the frames for his great Monet

show at the Museum of Modern Art in

1960, the undressed canvases looked a bit

like reproductions until you saw how they

began to hold the wall. Tough the hang-

ing had its eccentric moments, it read the

pictures relation to the wall correctly and,

in a rare act of curatorial daring, followed

up the implications. Seitz also set some of

the Monets fush with the wall. Continuous

with the wall, the pictures took on some

of the rigidity of tiny murals. Te surfaces

turned hard as the picture plane was over-

literalized. Te diference between the easel

picture and the mural was clarifed.

13. Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, Letter to

a friend, an open letter frst circulated by

email via the Documenta 13 newsletter and

recently published as the third volume of

the series 100 Notes100 Toughts (Kassel:

Hatje Kantz, 2011).

ADV

You might also like

- Paul O'neill PDFDocument185 pagesPaul O'neill PDFDabi Sorina88% (8)

- 10 Fundamental Questions of CuratingDocument145 pages10 Fundamental Questions of Curatingjan100% (11)

- A Brief History of Curating: By Hans Ulrich ObristFrom EverandA Brief History of Curating: By Hans Ulrich ObristRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- David Campany - The Cinematic (Documents of Contemporary Art) - The MIT Press (2007) PDFDocument118 pagesDavid Campany - The Cinematic (Documents of Contemporary Art) - The MIT Press (2007) PDFCarlos Barradas100% (1)

- How to Do Things with Art: The Meaning of Art's PerformativityFrom EverandHow to Do Things with Art: The Meaning of Art's PerformativityRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- Paul O'Neill - The Curatorial ConstellationDocument5 pagesPaul O'Neill - The Curatorial ConstellationDiego ParraNo ratings yet

- Talking Contemporary CuratingDocument13 pagesTalking Contemporary CuratingFedericoNo ratings yet

- The Exhibitionist Issue 6 PDFDocument76 pagesThe Exhibitionist Issue 6 PDFMariusz Urban100% (3)

- Ways of Curating - Hans Ulrich ObristDocument4 pagesWays of Curating - Hans Ulrich ObristdakowutuNo ratings yet

- Haacke, Hans - Working Conditions. The Writings of Hans HaackeDocument343 pagesHaacke, Hans - Working Conditions. The Writings of Hans HaackeBen Green67% (3)

- Issues in Curating Contemporary Art and PerformanceFrom EverandIssues in Curating Contemporary Art and PerformanceRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- Novelists and NovelsDocument609 pagesNovelists and Novelsclown23100% (22)

- Plan A Play ExperienceDocument7 pagesPlan A Play ExperienceFarahNo ratings yet

- A Practical Guide To Strategic Planning in Higher EducationDocument59 pagesA Practical Guide To Strategic Planning in Higher EducationPaLomaLujan100% (1)

- On Curating: Interviews with Ten International Curators: By Carolee TheaFrom EverandOn Curating: Interviews with Ten International Curators: By Carolee TheaRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- Bishop, Claire - Installation Art (No OCR)Document70 pagesBishop, Claire - Installation Art (No OCR)eu_tzup_medic100% (2)

- Curatorial Turn, Paul O'NeillDocument20 pagesCuratorial Turn, Paul O'NeillClarisa AppendinoNo ratings yet

- Rugoff EDSDocument4 pagesRugoff EDSTommy DoyleNo ratings yet

- The Exhibitionist Issue 4Document96 pagesThe Exhibitionist Issue 4Mariusz Urban100% (4)

- Curating Now 01Document24 pagesCurating Now 01madagaskar_2256100% (1)

- Manifesta Journal 7Document65 pagesManifesta Journal 7David Ayala AlfonsoNo ratings yet

- A Brief Outline of The History of Exhibition MakingDocument10 pagesA Brief Outline of The History of Exhibition MakingLarisa Crunţeanu100% (1)

- Manifesta Journal 8Document96 pagesManifesta Journal 8David Ayala AlfonsoNo ratings yet

- What Is A Curator - Claire BishopDocument8 pagesWhat Is A Curator - Claire BishopFelipe Castelo BrancoNo ratings yet

- Gombrich, E. M. - Art and Illusion - PhaidonDocument356 pagesGombrich, E. M. - Art and Illusion - PhaidonAg AndreiaNo ratings yet

- "Leading by Feel" by Rashid BahritdinovDocument2 pages"Leading by Feel" by Rashid BahritdinovRashid BahritdinovNo ratings yet

- Maria Lind Why Mediate ArtDocument17 pagesMaria Lind Why Mediate Artdenisebandeira100% (5)

- What Is The Public?: Ten Fundamental Questions of CuratingDocument17 pagesWhat Is The Public?: Ten Fundamental Questions of Curatingd7artNo ratings yet

- Exhibitionist #9Document85 pagesExhibitionist #9Cecilia Lee100% (1)

- The Culture Factory: Architecture and the Contemporary Art MuseumFrom EverandThe Culture Factory: Architecture and the Contemporary Art MuseumRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- After AllDocument139 pagesAfter Allemprex100% (3)

- Curating NowDocument175 pagesCurating NowmedialabsNo ratings yet

- Every Curator's HandbookDocument70 pagesEvery Curator's HandbooksophiacrillyNo ratings yet

- Living As Form - Chapter 1Document17 pagesLiving As Form - Chapter 1fmonar01100% (2)

- Curating As Critical Practice BibliographyDocument5 pagesCurating As Critical Practice BibliographyVal RavagliaNo ratings yet

- The Exhibitionist Issue 1 PDFDocument64 pagesThe Exhibitionist Issue 1 PDFFelipe PrandoNo ratings yet

- The Exhibitionist Issue 7: Curator's FavoritesDocument104 pagesThe Exhibitionist Issue 7: Curator's Favoriteshrabbs100% (1)

- What Is Conceptual ArtDocument28 pagesWhat Is Conceptual ArtKonstantin Koukos A90% (10)

- Maria Lind The Collaborative TurnDocument15 pagesMaria Lind The Collaborative TurnAkansha RastogiNo ratings yet

- The Intangibilities of Form. Skill and Deskilling in Art After The ReadymadeDocument3 pagesThe Intangibilities of Form. Skill and Deskilling in Art After The Readymadecjlass50% (2)

- Ways of Curating' Hal Foster ReviewDocument6 pagesWays of Curating' Hal Foster ReviewinsulsusNo ratings yet

- Art and Social CHange A Critical ReaderDocument480 pagesArt and Social CHange A Critical Readerilaria_vanni100% (2)

- Between the Black Box and the White Cube: Expanded Cinema and Postwar ArtFrom EverandBetween the Black Box and the White Cube: Expanded Cinema and Postwar ArtRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Defining Contemporary ArtDocument18 pagesDefining Contemporary Artfelipepena100% (5)

- Contemporary Exhibitions Art at Large I PDFDocument9 pagesContemporary Exhibitions Art at Large I PDFThamara VenâncioNo ratings yet

- Bruce Nauman, Collected WritingsDocument427 pagesBruce Nauman, Collected Writingsinsulsus100% (7)

- Art Contemporary Critical Practice: Reinventing Institutional CritiqueDocument287 pagesArt Contemporary Critical Practice: Reinventing Institutional Critiqueabeverungen91% (11)

- Bishop Claire Ed. - ParticipationDocument211 pagesBishop Claire Ed. - Participationmichimarzo100% (2)

- OnCurating Issue26Document113 pagesOnCurating Issue26sandraxy89No ratings yet

- A Companion To Curation PDFDocument508 pagesA Companion To Curation PDFAnonymous tLrDSTaFI100% (1)

- Michael Fried's "Art and Objecthood"Document16 pagesMichael Fried's "Art and Objecthood"Night Owl75% (4)

- Jeanpaul Martinon The Curatorial A Philosophy of Curating PDFDocument281 pagesJeanpaul Martinon The Curatorial A Philosophy of Curating PDFWilson Ledo50% (4)

- Exhibitionist #10Document85 pagesExhibitionist #10Cecilia Lee100% (1)

- Talking Art: The Culture of Practice & the Practice of Culture in MFA EducationFrom EverandTalking Art: The Culture of Practice & the Practice of Culture in MFA EducationNo ratings yet

- Architectural Video Mapping and The Promise of A New Media FaçadeDocument6 pagesArchitectural Video Mapping and The Promise of A New Media Façadeclown23No ratings yet

- Discerning The Grain of The Digital - On Render Ghosts and Google Street ViewDocument5 pagesDiscerning The Grain of The Digital - On Render Ghosts and Google Street Viewclown23No ratings yet

- Invitation Launching of Honesty CanteenDocument2 pagesInvitation Launching of Honesty CanteenRhylyahnaraRhon Palla PeraltaNo ratings yet

- Final Portfolio ReflectionDocument3 pagesFinal Portfolio Reflectioniloh2No ratings yet

- Careers in Hotel ManagementDocument9 pagesCareers in Hotel ManagementBoobeshkumar NamasivayamNo ratings yet

- Objective: Mr. Amol Pralhad Badarkhe Be Final Year Appeared E-Mail MOBILE NO: +91-8275934698Document3 pagesObjective: Mr. Amol Pralhad Badarkhe Be Final Year Appeared E-Mail MOBILE NO: +91-8275934698amolNo ratings yet

- AIO Assignments 2019 TEFLDocument6 pagesAIO Assignments 2019 TEFLatarafi0% (1)

- ACR On The Conduct of Mid Year Performance ReviewDocument7 pagesACR On The Conduct of Mid Year Performance ReviewIshiko GozaimasNo ratings yet

- Dimensional Approach in ReadingDocument14 pagesDimensional Approach in ReadingNhil Cabillon Quieta67% (9)

- The Art and Science of Victorian HistoryDocument312 pagesThe Art and Science of Victorian Historybadminton12100% (1)

- Final ReflectionDocument2 pagesFinal Reflectionapi-270431171No ratings yet

- Jadwal Interview Psikolog Calon FGDP MPE & Geotech PT Pamapersada Nusantara - SELESADocument5 pagesJadwal Interview Psikolog Calon FGDP MPE & Geotech PT Pamapersada Nusantara - SELESAHernandez ManikNo ratings yet

- Assignment - Final - POL 101Document2 pagesAssignment - Final - POL 101Pinaki RanjanNo ratings yet

- Talaan NG Pangkatang Pagtatasa NG Klase (TPPK)Document2 pagesTalaan NG Pangkatang Pagtatasa NG Klase (TPPK)lailahNo ratings yet

- Andhra Pradesh Grama - Ward SachivalayamDocument1 pageAndhra Pradesh Grama - Ward Sachivalayammamatha suneelNo ratings yet

- Expressing Hopes and DreamsDocument1 pageExpressing Hopes and DreamsDavindra Widi AthayaNo ratings yet

- Basilan State College-Administrative Officer VDocument1 pageBasilan State College-Administrative Officer VHarold Noel HidalgoNo ratings yet

- Questionnaire For Marry BrownDocument4 pagesQuestionnaire For Marry BrownHafeez AfzalNo ratings yet

- Basic Punjabi - Lesson 3 - Introducing Yourself and FamilyDocument34 pagesBasic Punjabi - Lesson 3 - Introducing Yourself and FamilyCulture AlleyNo ratings yet

- Program Design Inset 20133Document2 pagesProgram Design Inset 20133Jesc JessNo ratings yet

- FutebolDocument447 pagesFutebolflaviodomi100% (2)

- 0.a. Philosophy Course OutlineDocument3 pages0.a. Philosophy Course OutlineMarilyn DizonNo ratings yet

- Research On Gender Differences Chapter 1 To 3Document10 pagesResearch On Gender Differences Chapter 1 To 3Kathy Tamtech0% (1)

- Development Bank of The Philippines: Assistant Department Manager IIDocument10 pagesDevelopment Bank of The Philippines: Assistant Department Manager IIMuy AceitunaNo ratings yet

- Sannino Sutter 2011Document15 pagesSannino Sutter 2011Adriane CenciNo ratings yet

- 15 Hingga 19 Jan 2024Document9 pages15 Hingga 19 Jan 2024wesleyamerican_18448No ratings yet

- DLP 2Document5 pagesDLP 2Baby YanyanNo ratings yet

- PDF Trends of Nursing Lesson PlanDocument15 pagesPDF Trends of Nursing Lesson PlanDiksha chaudharyNo ratings yet

- College Packing ListDocument7 pagesCollege Packing ListGail OhagaNo ratings yet