Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Candidiasis Oral

Candidiasis Oral

Uploaded by

tristiarinaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Candidiasis Oral

Candidiasis Oral

Uploaded by

tristiarinaCopyright:

Available Formats

ORAL PATHOLOGY PP&A 635

Oral Candidiasis:

Clinical Manifestations, Diagnosis,

And Treatment

Karen Rossie, DDS, MS

James Guggenheimer, DDS

C

andidiasis (also known as

candidosis) is caused by an

infection or overgrowth with

the fungus Candida; the species

most commonly involved is

Candida albicans. Candidiasis affects

certain groups of the population, eg,

the debilitated, elderly, infants, denture

wearers, and the immunocompromised,

1

with prevalence of 10% to 15%.

2

Among

the general population, 25% to 75%

are carriers.

3

Oral candidiasis may present

in a number of dissimilar forms.

1,4

The

clinical appearance is influenced by

the severity, chronicity, and location of

the infection. Acute infections tend

to be diffuse and are associated with symp-

toms of soreness or burning. Chronic

infections generally produce fewer symp-

toms and can be diffuse or localized to

certain areas of the mouth. The oral man-

ifestations of candidiasis are varied, but

some major forms can be distinguished;

they may occur separately or in combi-

nation with each other.

ORAL CLINICAL

MANIFESTATIONS

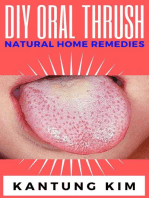

Pseudomembranous Candidiasis

Commonly called thrush or a yeast

infection, this is the most widely recog-

nized form of oral candidiasis (Figure 1),

visible as soft, white, cheesy material

that wipes off, revealing red, inflamed

mucosa. The infection is often acute but

may be chronic, depending upon the

underlying etiologic factors. Following

a course of antibiotics, a typical onset

can be sudden. Often, there are symptoms

of oral soreness or a burning sensation,

distributed diffusely throughout the

oral cavity. Some previous reports have

described an ulcerated surface underlying

the pseudomembrane of candidiasis;

however, candidiasis itself does not typ-

ically produce ulceration. Therefore, if

the underlying mucosa is ulcerated,

another diagnosis should be considered.

The white pseudomembrane overlying

an ulceration can be mistaken for can-

didiasis. However, an ulcer membrane

is more tenacious, and if it is wiped off,

a raw bleeding ulcer bed will be exposed.

There are several other common white

intraoral materials that wipe off and

must, therefore, be distinguished from

candidiasis. These include bacterial plaque

and materia alba (normal sloughing of

epithelial cells), which may accumulate,

particularly on the gingiva in debilitated

patients with poor hygiene. An uncom-

mon reaction to certain mouthwashes

and toothpastes, presenting as a thin

filmy white material, has also been ob-

served. These lesions can vaguely resemble

candidiasis, although they are less thick

and less tenacious.

Erythematous (Atrophic)

Candidiasis

This form of candidiasis presents with

red, inflamed mucosa (Figure 2). Its

appearance is identical to the mucosa,

revealed under the pseudomembranous

form when the white material is wiped

off. The patient complains of a sore, burn-

ing mouth. There may be a little pseu-

domembrane present in the morning,

but it may have sloughed off by the time

the patient presents to the dental office.

Denture Stomatitis (Denture Sore

Mouth)

Denture stomatitis is a form of erythema-

tous candidiasis in which the diffuse red-

ness of the mucosa corresponds to the

area covered by the denture (Figure 3).

It is most evident on the palate and may

occur in acute or chronic form. It is gen-

erally caused by a mixed microflora of

Candida plus bacteria.

5

Frequently, this

form of candidiasis is not an actual in-

fection, since the yeasts or pseudohyphae

Karen Rossie, DDS, MS, is Associate

Professor, Dental Specialty, Oral Medicine,

Department of Oral and Maxillofacial

Pathology, School of Dental Medicine,

University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh,

Pennsylvania.

James Guggenheimer, DDS, is Professor,

Dental Specialty, Oral Medicine, Depart-

ment of Oral Medicine and Pathology,

School of Dental Medicine, University of

Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Address correspondence to:

Karen Rossie, DDS, MS

University of Pittsburgh

School of Dental Medicine

Department of Oral Medicine

and Pathology

Pittsburgh, PA 15261

Tel: 412-648-8637

Fax: 412-383-9142

22

Oral candidiasis (candidosis) is an infection with multiple manifestations. To prevent prolongation of undiagnosed cases, it is

essential that the dental clinicians have an understanding of the etiology, pathogenesis, and treatment of this disease. The learn-

ing objective of this article is the identification of the various clinical features of candidiasis. The underlying causes of oral can-

didiasis include antibiotic therapy, poor denture hygiene, xerostomia, immune deficiencies, diabetes, and some less common

conditions. Candidal infection may be superimposed on other mucosal diseases and may disguise the underlying disease. The

diagnosis is established using clinical appearance and patient history, and it may require diagnostic tests. A significant segment

of the population carries intraoral Candida, without any symptoms of infection, complicating the use of diagnostic tests.

are not evident in the epithelium of

biopsy specimens.

1

The inflammation

may be a reaction to the mixed micro-

organisms, held in place by the denture.

Median Rhomboid Glossitis

Another form of erythematous (atrophic)

candidiasis, median rhomboid glossitis,

presents as an atrophic area in the midline

dorsal surface of the posterior portion

of the tongue (Figure 4). The atrophy

consists of a loss of the tongue papillae,

particularly the filiform papillae, resulting

in a well-demarcated, localized smooth

area. The intensity of inflammation varies.

Median rhomboid glossitis had previously

been thought to represent a developmen-

tal anomaly; now it is recognized that

most cases are caused by candidal infection.

Evidence includes the presence of the

microorganisms in biopsied lesions and

the resolution of lesions with antifungal

medications. Localization to this area

of the tongue may be due to stasis during

swallowing as it comes in contact with

the palate. While the midline posterior

dorsal tongue is the most common

location for the lesion, it may also occur

in patches elsewhere on the dorsal tongue

and may, therefore, resemble migratory

glossitis (geographic tongue). These

two conditions can be distinguished,

since migratory glossitis generally con-

sists of multiple atrophic patches and

may display a zone of white hyperplasia

at its border with a red inflamed zone

just inside the atrophic area. Occasionally,

this distinction can be problematic, and

a cytologic smear may be required to

demonstrate the presence of Candida.

Localized Palatal Redness

Redness in the middle of the hard palate

is another form of erythematous can-

didiasis, particularly when it corresponds

to median rhomboid glossitis in the

area of the tongue with which it comes

in contact. These localized erythematous

Figure 3. Erythematous candidiasis: Denture stomatitis. The redness of the mucosal tissue

corresponds to the area covered by the denture.

Figure 2. Erythematous candidiasis: Palatal erythema. Note red, inflamed mucosa.

Candidiasis (also known as

candidosis) is caused by an

infection or overgrowth with

the fungus Candida ...

Figure 1. Acute pseudomembranous candidiasis. Note the presence of soft, white,

cheesy material.

636 Vol. 9, No. 6 ORAL PATHOLOGY

patches may be subtle, but they can

confirm a suspected case of candidiasis,

when present.

Angular Cheilitis

This term refers to inflammation at the

corners of the mouth. The clinical signs

and symptoms include redness and sore-

ness, with possible formation of fissures

and crusting ulcers (Figure 5). A mixed

infection of Candida plus certain bacteria

is responsible for the infection.

6

Angular

cheilitis is pronounced in individuals

who have deep skin folds at the angles

of the mouth. This occurs in individuals

with overclosed vertical dimension

(Figure 6). Presumably the fold of skin

provides an ideal environment for the

microorganisms to proliferate. Angular

cheilitis is frequently associated with an

intraoral candidal infection. Occasionally,

perioral skin around the entire mouth

is infected, most often in children.

Chronic Hyperplastic Candidiasis

This uncommon form of candidiasis

involves a white macular or plaque lesion

(leukoplakia) that does not wipe off. It

is often located on the buccal mucosa

just inside the commissures of the lip,

presenting as a speckled white lesion,

which becomes nodular and fissured as

it progresses (Figure 7). Generally, the

candidal infection is superimposed on

an underlying leukoplakia (Figure 8).

Treatment of these lesions with anti-

fungal medications may produce some

improvement but will not accomplish

complete resolution. Infrequently, the

leukoplakia may disappear completely

in response to antifungal therapy, sug-

gesting that the lesion is caused entirely

by the fungus. Nevertheless, candidi-

asis may have a role in carcinogenesis.

7

Leukoplakia lesions that do not resolve

completely with antifungal therapy should

be biopsied to rule out a premalignant

or a malignant condition.

Figure 6. Angular cheilitis associated with denture wearing and closed vertical dimension.

Figure 5. Angular cheilitis following a long course of antibiotic therapy.

It is important

to distinguish between

carriers of Candida ...

and actual infection.

Figure 4. Erythematous candidiasis: Median rhomboid glossitis. An atrophic area is

demonstrated in the midline dorsal surface of the posterior portion of the tongue.

ORAL PATHOLOGY PP&A 637

DIAGNOSTIC TESTS

Tests for the diagnosis of candidiasis

include the cytologic smear or exfoliative

cytology, culture, and KOH (potassium

hydroxide) preparation, designed to detect

the microorganism itself. It is important

to distinguish between carriers of

Candida 25% to 75% of the population

and actual infection.

1

Most carriers do

not have an actual infection. The white

material that wipes off in pseudomem-

branous candidiasis is composed primarily

of numerous candidal microorganisms

in the pseudohyphae or yeast forms.

This material can be removed and tested.

With a chronic infection, the pseudo-

hyphal form becomes embedded in the

superficial layers of the epithelium.

Superficial pseudohyphae can be removed

together with surface epithelial cells by

scraping the surface of a suspected lesion

with a wet tongue depressor. The material

removed is applied to a glass slide that

is sprayed with a cytological fixative and

air dried (Figure 9). The slide is then

stained in a laboratory and examined

microscopically (Figure 10).

The presence of Candida can also

be demonstrated immediately in an

unfixed smear using a technique called

a KOH preparation. The KOH solution

dissolves the epithelial cells but does

not dissolve the Candidamicroorganisms.

The yeasts and pseudohyphae remaining

on the slide can then be microscopically

observed. However, many of the micro-

organisms may be lost during processing

with the KOH technique, and this may

result in a false negative test.

A biopsy may be indicated for chronic

red and/or white lesions, since chronic

candidiasis can resemble the potentially

premalignant or malignant clinical con-

ditions leukoplakia and erythroplakia.

The microscopic appearance includes a

mildly thickened layer of parakeratin,

which may include small microabscesses

Figure 8. White nodular leukoplakia, usually found on buccal mucosa just inside

commissure is an uncommon form of chronic Candida infection.

The causes ... either

alter the balance of normal

oral microflora ... or compromise

the immune system.

Figure 9. Cytologic smear: Applying cytologic scrapings to a glass slide.

Figure 7. White intraoral plaque may have a superimposed Candida infection.

638 Vol. 9, No. 6 ORAL PATHOLOGY

containing neutrophils (Figure 11).

The typical epithelium is hyperplastic

with elongated rete pegs. There is a

mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate

in the lamina propria, consisting pri-

marily of lymphocytes. Staining the

biopsy specimen reveals varying numbers

of pseudohyphae.

ETIOLOGY/PATHOGENESIS

The causes of oral candidiasis either

alter the balance of the normal oral

microflora, alter the oral environment,

or compromise the immune system.

1,2,4,5,7

Some systemic diseases, such as HIV

infection or diabetes mellitus, place

the patient at risk for candidiasis through

more than one mechanism.

Antibiotics, especially the broad spec-

trum group such as tetracycline, are likely

to alter the oral microflora and are a com-

mon cause. Acute pseudomembranous

candidiasis may develop after only a short

course of antibiotics. Histories of lengthy

treatment with antibiotics for resistant

bacterial infections are frequently obtained

from patients with chronic candidiasis.

Dentures are another common ini-

tiator of candidiasis by altering the oral

environment. A mixture of Candida and

other microorganisms can actually live

in the nonpolished inner surfaces of the

denture acrylic.

6

A low degree of saliva increases a

patients risk for candidiasis,

8

particularly

the more severe forms of dry mouth,

such as those caused by several medi-

cations, Sjgrens syndrome, or radiation

therapy that involves the salivary glands.

The milder form of candidiasis seen in

xerostomia is often the atrophic form

in which the patient presents with a red,

burning mouth, and the white pseudo-

membrane may not be present.

Immunosuppression, particularly of

the cell-mediated immune system, such

as occurs with HIV infection, frequently

results in severe, persistent oropharyngeal

Figure 10. Cytologic smear: Microscopic appearance of Candida pseudohyphae in cyto-

logic smear, stained with periodic acid and Schiff reagents.

Figure 11. Microscopic appearance of Candida pseudohyphae invading superficial keratin

in histologic section of infected mucosa, stained with periodic acid and Schiff reagents.

Tests for the diagnosis of

candidiasis include cytologic

smear or exfoliative cytology,

culture, and KOH preparation.

Figure 12. Case 1. Patient at presentation, following 1 month on amoxicillin; the lesions

have been diagnosed as medial rhomboid glossitis.

ORAL PATHOLOGY PP&A 639

candidiasis.

9

Immunosuppressed indi-

viduals can manifest any of the clinical

forms; development of unusual genotypes

of Candida is of particular concern, since

they may be resistant to standard anti-

fungal therapies. Corticosteroid use is

another common cause of immunosup-

pression that may initiate candidiasis.

10

Patients using immunosuppressive med-

ications for long periods include those

with autoimmune diseases and organ

or bone marrow transplant recipients.

Chemotherapeutic medications for treat-

ment of cancer can similarly initiate

candidiasis.

11

A rare disorder called chronic muco-

cutaneous candidiasis is characterized

by persistent oral candidiasis and involve-

ment of the skin and nail beds.

12

These

syndromes are often inherited, but spo-

radic cases may occur.

Non-insulin- and insulin-dependent

diabetes mellitus are associated with

an increased rate of candidiasis and an

increased carrier rate of the micro-

organism.

13

Possible contributing factors,

reported in diabetes, include decreased

neutrophil function, xerostomia, and

increased glucose in the saliva.

14

TREATMENT

Topical treatment of candidiasis can be

administered in the form of a rinse,

troche, or pastille of certain antifungal

medications (eg, clotrimazole, nystatin).

1,10

Medication forms which dissolve slowly,

such as the troche or pastille, can be

more effective than rinses, since they

are in contact with the infected mucosa

over a longer period of time. Patients

with xerostomia may find it difficult to

dissolve topical medications; for them,

a rinse may be more comfortable. Topical

treatment for the adult patient requires

rinsing 4 times per day or dissolving

on a troche or pastille 5 times per day

for 10 days. An initial course of antifungal

medication is typically 10 days; however,

Figure 13. The same patient at initial presentation with erythematous lesion on the

corresponding area of palate.

Figure 15A. Case 2. Patient at presentation, with median rhomboid glossitis. 15B.

Following 2 weeks of treatment with nystatin rinses, the patient demonstrates partial resolu-

tion.

A B

Figure 14. Following 10 days of treatment with nystatin pastilles, the patient demonstrates

partial resolution of median rhomboid glossitis.

The microscopic appearance,

includes a ... layer of parakeratin,

which may include small micro-

abscesses containing neutrophils.

640 Vol. 9, No. 6 ORAL PATHOLOGY

treatment should last at least twice as

long as the time it takes to alleviate signs

and symptoms.

10

A second course of

antifungal medication may be required,

particularly in chronic forms of candidi-

asis. Antifungal rinses may have a high

sugar content, which should be taken

into consideration when prescribed for

long intervals in caries-prone patients.

The new varieties of systemic anti-

fungal medications elicit improved treat-

ment response, have fewer toxic effects,

and are used more frequently.

10

They

include fluconazole, which can be

administered in a single dose of 100 mg

per day (200 mg on the first day) in an

adult for at least 2 weeks.

15

The single

dose may result in improved patient

compliance. The drug is also available in

an oral suspension, but dosage should

be the same as for tablets, due to rapid

and almost complete absorption. There

is some risk of liver toxicity in the

imidazole group of medications (eg,

clotrimazole, itraconazole, fluconazole,

and ketoconazole), and liver function

tests should be obtained periodically.

10

Long-term dosage should be avoided

to limit possible adverse effects.

Mixed infections, such as angular

cheilitis, may benefit from topical medi-

cations (eg, clioquinol) that have antifungal

and antibacterial properties.

15

Cases with-

out a significant bacterial component

may respond well to the above antifungal

medications in cream or ointment form

alone. For angular cheilitis, any intraoral

infection should be treated in conjunction

with the extraoral problem, otherwise

the angles of the mouth may be reinfected.

In cases of denture stomatitis, the

denture and the oral cavity must be

treated in order to avoid reinfection.

10

Dentures should be soaked in commer-

cially available antiseptics or in 0.12%

chlorhexidine gluconate. An effective

disinfectant can be prepared from a

1:50 dilution of sodium hypochlorite

(chlorine bleach) in water. All dentures

should be carefully rinsed with water

prior to reseating. Antifungal ointments

or creams (eg, nystatin, clotrimazole,

or ketoconazole) can also be applied to

the inside of the denture to hold the

medication against the affected area.

Control of any underlying systemic

diseases is an important consideration

in the treatment of oral candidiasis.

Chlorhexidine may be effective for main-

tenance following resolution of an infection

in a patient who is predisposed to recurrent

candidiasis.

10

CASE PRESENTATION

Case 1

A 29-year-old female patient presented

with persistent pain in a carious man-

dibular right second molar. The patient

had periodically taken amoxicillin when-

ever the severity of the symptoms had

increased, and had taken it for 1 week

prior to presentation. There was no

other significant medical history. The

oral examination revealed a slightly

raised, inflamed, and atrophic area in

the posterior central portion of the

tongue (Figure 12). An area of inflam-

mation also involved the vault of the

hard palate (Figure 13). Cytologic smears

from the tongue and palatal lesions

exhibited large numbers of Candida

pseudohyphae.

The diagnosis was candidiasis

(median rhomboid glossitis), apparently

induced by antibiotics. The kissing

lesion of the hard palate was also con-

firmed as candidiasis. The patient was

treated with lozenges (eg, nystatin),

200,000 units held intraorally 4 times

daily and at bedtime (Figure 14). The

tongue and palate lesions had resolved

3 weeks posttreatment.

Case 2

A 72-year-old male patient presented

complaining of soreness and burning of

the tongue. The symptoms had persisted

for 3 weeks. The patient was edentulous

and had complete maxillary and mandibu-

lar dentures. The medical history included

rheumatoid arthritis with considerable

pain and stiffness that had become

increasingly refractory to treatment.

Six months prior to the onset of the oral

symptoms, the patients physician had

prescribed a regimen of prednisone,

10 mg per day, and methotrexate, 2.5 mg

three times per week. Examination of

the oral cavity revealed an erythema-

tous, atrophic strip down the midline of

the dorsal surface of the dorsal tongue

(Figure 15A). The clinical diagnosis was

candidiasis (median rhomboid glossitis)

secondary to the medications; it was

confirmed with cytologic smears. The

patient was placed on a regimen of nys-

tatin pastilles, 200,000 units dissolved

in the mouth 4 times daily and at bed-

time. Two-week follow-up revealed an

improvement of the tongue symptoms

and appearance (Figure 15B).

CONCLUSION

Oral candidiasis is common, but diagnosis

can be confusing, due to the variety of

manifestations which it demonstrates.

Some cases of oral candidiasis may remain

undiagnosed, due to the subtle appear-

ance of the disease to the untrained eye.

Other cases may be misdiagnosed due to

a resemblance to other conditions. Unrecog-

nized cases can result in needless suffering

by the patient, with symptoms that can

be effectively and rapidly alleviated by

antifungal medications. Therefore, dentists

should have an understanding of the many

faces of candidiasis as well as its etiology,

pathogenesis, and treatment.

REFERENCES

1. Allen CM. Diagnosing and managing oral can-

didiasis. J Am Dent Assoc 1992;123(1):77-78.

2. Odds FC. Candida and Candidosis. 2nd ed.

London, England: Balliere Tindall, 1988.

3. Fotos PG, Vincent SD, Hellstein JW. Oral candi-

dosis. Clinical, historical, and therapeutic fea-

tures of 100 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral

Pathol 1992;74(1):41-49.

4. Fotos PG, Hellstein JW. Candida and candidosis.

Epidemiology, diagnosis and therapeutic manage-

ment. Dent Clin North Am 1992;36(4):857-878.

5. Theilade E, Budtz-Jorgensen E. Predominant

cultivable microflora of plaque on removable

dentures in patients with denture-induced stom-

atitis. Oral Microbiol Immunol 1988;3(1):8-13.

6. MacFarlane TW, Helnarska SJ. The microbiology of

angular cheilitis. Br Dent J 1976;140(12):403-406.

7. Field EA, Field JK, Martin MV. Does Candida

have a role in oral epithelial neoplasia? J Med Vet

Mycol 1989;27(5):277-294.

8. Atkinson JC, Wu AJ. Salivary gland dysfunction:

Causes, symptoms, treatment. J Am Dent Assoc

1994;125(4):409-416.

9. Coleman DC, Bennett DE, Sullivan DJ, et al. Oral

Candida in HIV infection and AIDS: New per-

spectives/new approaches. Crit Rev Microbiol

1993;19(2):61-82.

10. Fotos PG, Lilly JP. Clinical management of oral

and perioral candidosis. Dermatol Clin 1996;14

(2):273-280.

11. Rodu B, Griffin IL, Gockerman JP. Oral candidiasis

in cancer patients. South Med J 1984;77(3):312-314.

12. Porter SR, Haria S, Scully C, Richards A. Chronic

candidiasis, enamel hypoplasia, and pigmentary

anomalies. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol

1992;74(3):312-314.

13. Bartholomew GA, Rodu B, Bell DS. Oral candidi-

asis in patients with diabetes mellitus: A thor-

ough analysis. Diabetes Care 1987;10(5):607-612.

14. Aly FZ, Blackwell CC, Mackenzie DA, et al.

Factors influencing oral carriage of yeasts among

individuals with diabetes mellitus. Epidemiol

Infect 1992;109(3):507-518.

15. Drug Facts and Comparisons, 1996 edition. Facts

and Comparisons, St. Louis, MO: Wolters Kluwer,

1996.

ORAL PATHOLOGY PP&A 641

642 Vol. 9, No. 6 ORAL PATHOLOGY

1. The species of Candida most often responsible for

candidiasis is:

a. Candida candidosis.

b. Candida globrata.

c. Candida tropicalis.

d. Candida albicans.

2. Candidiasis is also commonly called all of the

following EXCEPT:

a. Thrush.

b. Trench mouth.

c. Yeast infection.

d. Candidosis.

3. The following are common oral manifestations of

candidiasis EXCEPT:

a. White material that wipes off.

b. Median rhomboid glossitis.

c. Ulceration.

d. Erythematous mucosa.

4. The pseudomembrane of pseudomembranous

candidiasis is mostly composed of:

a. Pseudohyphae and yeasts.

b. Sloughing epithelium.

c. Fibrin.

d. Necrotic cells.

5. Which of the following diseases is frequently

associated with candidiasis?

a. Osteoporosis.

b. Herpes gingivostomatitis.

c. HIV infection.

d. Colon cancer.

6. If a leukoplakia lesion infected with Candida does

NOT resolve following 4 weeks on an antifungal

medication, the dentist should:

a. Continue antifungal medication for 2 months.

b. Biopsy the lesion.

c. Discontinue antifungal medication and observe

for 6 months.

d. Give an antibiotic.

7. Which of the following medications frequently

contributes to the development of candidiasis?

a. Corticosteroids.

b. Clotrimazole.

c. Insulin.

d. Ibuprofen.

8. A special stain used to demonstrate Candida in

cytologic smears or biopsy specimens is:

a. Acid fast bacillus.

b. Mucicarmine.

c. Periodic acid and Schiff reagents.

d. Alcian blue.

9. Which form of candidiasis is frequently combined

with a bacterial infection?

a. Pseudomembranous candidiasis.

b. Angular cheilitis.

c. Median rhomboid glossitis.

d. Chronic hyperplastic candidiasis.

10. A potentially serious side effect of the imidazole

antifungal medications is:

a. Lichen planus.

b. Renal failure.

c. Diabetes mellitus.

d. Liver toxicity.

To submit your CE Exercise answers, please use the enclosed Answer Card (one for all 4 CE articles) found

opposite page 610, and complete it as follows: 1) Complete the address; 2) Identify the Article/Exercise Number;

3) Place an X in the appropriate answer box for each question for each exercise. Return the completed card.

The 10 multiple-choice questions for this Continuing Education (CE) exercise are based on the article Oral

candidiasis: Clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and treatment by Karen Rossie, DDS, MS, and James Guggenheimer,

DDS. This article is on Pages 635-641. Answers to this exercise will be published in the October 1997 issue of PP&A.

Learning Objectives:

This article describes the various clinical features of oral candidiasis, emphasizing their typical appearance, characteristics, and

locations. The underlying causes and therapy are discussed. Upon reading and completion of this exercise, the reader should have:

Knowledge of signs and symptoms of oral candidiasis, required for establishing an accurate diagnosis.

Ability to treat or refer the patient.

Continuing Education (CE) Exercise No. 22

sm

UTHSCSA

22

You might also like

- Fungal Diseases of The Oral MucosaDocument5 pagesFungal Diseases of The Oral MucosaManar AlsoltanNo ratings yet

- Oral ThrushDocument29 pagesOral ThrushTushar KhuranaNo ratings yet

- CandidiasisDocument20 pagesCandidiasisMoustafa Hazzaa100% (1)

- Candidiasis: International Class MakalahDocument16 pagesCandidiasis: International Class MakalahIrwan AzizNo ratings yet

- Variasi Normal Rongga MulutDocument18 pagesVariasi Normal Rongga MulutRafi Kusuma Ramdhan SukonoNo ratings yet

- Oral Manifestations of Systemic DiseaseDocument10 pagesOral Manifestations of Systemic DiseasedrnainagargNo ratings yet

- Oral Candidiasis: Madhu Priya.MDocument4 pagesOral Candidiasis: Madhu Priya.MinventionjournalsNo ratings yet

- White and Red Lesion Lecture 1 - DR Ameena Ryhan DiajilDocument43 pagesWhite and Red Lesion Lecture 1 - DR Ameena Ryhan Diajilفاطمة احمد غضبان الزياديNo ratings yet

- Red and White Lesions of The Oral Mucosa: DR - Wisam RasoolDocument43 pagesRed and White Lesions of The Oral Mucosa: DR - Wisam RasoolFlorida ManNo ratings yet

- Oral CandidasisDocument39 pagesOral CandidasisArmada Eka FredianNo ratings yet

- Manchas Blancas y RojasDocument16 pagesManchas Blancas y RojasJosué Zuriel OrtizNo ratings yet

- White, Red, and Mixed Lesions of Oral Mucosa A Clinicopathologic Approach To DiagnosisDocument17 pagesWhite, Red, and Mixed Lesions of Oral Mucosa A Clinicopathologic Approach To DiagnosisAlexandra LupuleasaNo ratings yet

- Oral Candidiasis: Etiology and PathogenesisDocument5 pagesOral Candidiasis: Etiology and PathogenesisNovita Indah PratiwiNo ratings yet

- 455.full CandidiasisDocument6 pages455.full CandidiasisIdris Siddiq CuakepNo ratings yet

- A Clinical Approach White LesionDocument5 pagesA Clinical Approach White LesionTirta KusumaNo ratings yet

- 961 Atharav CandidiasisDocument25 pages961 Atharav CandidiasisDevender MittalNo ratings yet

- Angular Chelitis - StatPearls - NCBI BookshelfDocument15 pagesAngular Chelitis - StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelfmichaelarchangelus7No ratings yet

- Fungal Infection, FinalDocument26 pagesFungal Infection, FinalFatima TagNo ratings yet

- Icd 10Document59 pagesIcd 10Hendra PranotogomoNo ratings yet

- Cabt 10 I 1 P 1Document5 pagesCabt 10 I 1 P 1Hanifah Nailul AmaniaNo ratings yet

- Candidiasis MucosalDocument112 pagesCandidiasis MucosalTara Sefanya KairupanNo ratings yet

- Oral Candidiasis An Overview and Case ReportDocument7 pagesOral Candidiasis An Overview and Case ReportPutri NingrumNo ratings yet

- Haider OralllllllllllllllllllllllDocument13 pagesHaider OralllllllllllllllllllllllAli YehyaNo ratings yet

- Oral CandidiasisDocument4 pagesOral CandidiasisAnish RajNo ratings yet

- Fungal OriginDocument1 pageFungal OriginAnnaNo ratings yet

- Applied Sciences: The Pseudolesions of The Oral Mucosa: Di Diagnosis and Related Systemic ConditionsDocument8 pagesApplied Sciences: The Pseudolesions of The Oral Mucosa: Di Diagnosis and Related Systemic Conditionssiti baiq gadishaNo ratings yet

- ContempClinDent111-3628383 - 100443 HIVDocument5 pagesContempClinDent111-3628383 - 100443 HIVthomas purbaNo ratings yet

- Common Oral Lesions: by Joseph Knight, PA-CDocument7 pagesCommon Oral Lesions: by Joseph Knight, PA-CAnonymous k8rDEsJsU1No ratings yet

- Stomatitis. Aetiology and A Review. Part 2. Oral Diseases Caused Candida SpeciesDocument7 pagesStomatitis. Aetiology and A Review. Part 2. Oral Diseases Caused Candida SpeciesIzzahalnabilah_26No ratings yet

- Ulcers and Vesicles2Document24 pagesUlcers and Vesicles2Kelly MayerNo ratings yet

- Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology: Seminar OnDocument26 pagesDepartment of Oral Medicine and Radiology: Seminar OnPatriciaXavier100% (1)

- Oral UlcerationDocument10 pagesOral Ulcerationمحمد حسنNo ratings yet

- Candidiasis (Candidosis)Document17 pagesCandidiasis (Candidosis)h8j5fnyh7dNo ratings yet

- Lecture 1: Bacterial&fungal Infection With Damage of Mucouse of Oral CavityDocument35 pagesLecture 1: Bacterial&fungal Infection With Damage of Mucouse of Oral CavityParisa PourkhosrowNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Oral MedicineDocument17 pagesPediatric Oral MedicinebanyubiruNo ratings yet

- Oral Findings in Secondary Syphilis: Zela Puteri Nurbani 1506668694Document15 pagesOral Findings in Secondary Syphilis: Zela Puteri Nurbani 1506668694adnanfananiNo ratings yet

- Ojsadmin, 1464Document6 pagesOjsadmin, 1464Akun MoontonNo ratings yet

- At-A-Glance: KandidiasisDocument19 pagesAt-A-Glance: Kandidiasisketty putriNo ratings yet

- Oral Candidiasis An Opportunistic Infection A ReviewDocument5 pagesOral Candidiasis An Opportunistic Infection A ReviewDino JalerNo ratings yet

- Pathogenesis and Treatment of Oral CandidosisDocument20 pagesPathogenesis and Treatment of Oral CandidosiselisabethpriskaNo ratings yet

- Candidiasis MedscapeDocument36 pagesCandidiasis MedscapesummiyaNo ratings yet

- RKDF Dental College Bhopal: Department of PeriodonticsDocument40 pagesRKDF Dental College Bhopal: Department of Periodonticsananya saxenaNo ratings yet

- Candida-Associateddenturestomatitis - Aetiologyand Management: Areview - Part2.Oraldiseasescausedby Candida SpeciesDocument7 pagesCandida-Associateddenturestomatitis - Aetiologyand Management: Areview - Part2.Oraldiseasescausedby Candida SpeciesDentist HereNo ratings yet

- Oral Mucosal Lesions in Children: Upine PublishersDocument3 pagesOral Mucosal Lesions in Children: Upine PublishersbanyubiruNo ratings yet

- Approach To Oral LesionsDocument53 pagesApproach To Oral LesionsUmut YücelNo ratings yet

- Lip LesionsDocument4 pagesLip LesionsGhada AlqrnawiNo ratings yet

- Candida Info UptodateDocument40 pagesCandida Info UptodateRamona RahimianNo ratings yet

- MoniliasisDocument2 pagesMoniliasis4gen_7100% (1)

- Contents:: Infectious DiseasesDocument87 pagesContents:: Infectious DiseasesdrnainagargNo ratings yet

- CandidiasisDocument6 pagesCandidiasisNabrazz SthaNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis and Treatment of Oral CandidosisDocument7 pagesDiagnosis and Treatment of Oral CandidosisYerly Ramirez MuñozNo ratings yet

- 3 Benign Inflammatory LesionsDocument8 pages3 Benign Inflammatory LesionsalbaablyNo ratings yet

- A. What Is Perio-Endo Lesion?Document6 pagesA. What Is Perio-Endo Lesion?Emeka NnajiNo ratings yet

- Oral CandidiasisDocument3 pagesOral CandidiasisGoutham MkNo ratings yet

- 588 Article+Text 1884 1 10 20220107Document9 pages588 Article+Text 1884 1 10 20220107Dave PutraNo ratings yet

- 39 Ahmed EtalDocument6 pages39 Ahmed EtaleditorijmrhsNo ratings yet

- CandidiasisDocument51 pagesCandidiasisLincy JohnyNo ratings yet

- b.8 Oral CandidiasisDocument14 pagesb.8 Oral Candidiasisbryamjbriceno100% (1)

- Fixed Appliances - Open Coiled Space Regainer - Jackscrew Space Regainer - Gerber Space RegainerDocument19 pagesFixed Appliances - Open Coiled Space Regainer - Jackscrew Space Regainer - Gerber Space RegainertristiarinaNo ratings yet

- Prosthetic TreatmentDocument23 pagesProsthetic Treatmenttristiarina0% (1)

- Research ArticleDocument11 pagesResearch ArticletristiarinaNo ratings yet

- Polishing Amalgam RestorationsDocument39 pagesPolishing Amalgam RestorationsMuad AbulohomNo ratings yet

- Perbedaan Jumlah Actinobacillus Actino Mycetem Comitans Pada Periodontitis Agresif Berdasarkan Jenis KelaminDocument1 pagePerbedaan Jumlah Actinobacillus Actino Mycetem Comitans Pada Periodontitis Agresif Berdasarkan Jenis KelamintristiarinaNo ratings yet

- Nteraksi Obat Dalam Praktek Edokteran Igi: Drg. Yayun Siti Rochmah SPBMDocument29 pagesNteraksi Obat Dalam Praktek Edokteran Igi: Drg. Yayun Siti Rochmah SPBMtristiarinaNo ratings yet

- Partial Odontectomy BrochureDocument2 pagesPartial Odontectomy BrochuretristiarinaNo ratings yet