Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Aortic Aneurysm

Aortic Aneurysm

Uploaded by

allyx_mCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Aortic Aneurysm

Aortic Aneurysm

Uploaded by

allyx_mCopyright:

Available Formats

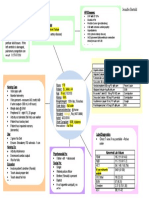

Modifiable Factors

- Cigarette smoking

- Atherosclerosis

- Trauma

- Hypertension

- Arteritis

- Obesity

- Presence of bicuspid aortic valve

Non Modifiable Factors

- Age (60 )

- Gender (Male)

- Genetics

Accumulation of lipids, fibrin, debris, cholesterol crystals

Plaque formation

Atherosclerosis

Ulcerate (brake Open)

Degenerative changes

Damaged endothelial lining

Loses elasticity & becomes weak

Dilation of Aorta

Development of thrombus

Narrows the vessel

Swept along by blood

Emboli

Aortic Aneurysm

An aortic aneurysm is an abnormal enlargement or bulging of the wall of the aorta. An aneurysm can

occur anywhere in the vascular tree. The bulge or ballooning may be defined as a:

y Fusiform: Uniform in shape, appearing equally along an extended section and edges of the aorta.

y Saccular aneurysm: Small, lop-sided blister on one side of the aorta that forms in a weakened

area of the aorta wall.

History

The first historical records about AAA are from Ancient Rome in the 2nd century AD, when Greek

surgeon Antyllus tried to treat the AAA with proximal and distal ligature, central incision and removal of

thrombotic material from the aneurysm.

However, attempts to treat the AAA surgically were unsuccessful until 1923. In that year, Rudolph Matas

(who also proposed the concept of endoaneurysmorrhaphy), performed the first successful aortic ligation

on a human.

Other methods that were successful in treating the AAA included wrapping the aorta with polyethene

cellophane, which induced fibrosis and restricted the growth of the aneurysm.

Albert Einstein was operated on by Rudolf Nissen with use of this technique in 1949, and survived five

years after the operation. Endovascular aneurysm repair was first performed in the late 1980s and has

been widely adopted in the subsequent decades.

AAA is uncommon in individuals of African, Asian, and Hispanic heritage.

There are 15,000 deaths yearly in the U.S. secondary to AAA rupture. The frequency varies strongly

between males and females. The peak incidence is among males around 70 years of age, the prevalence

among males over 60 years totals 2-6%.

The frequency is much higher in smokers than in non-smokers (8:1), and the risk decreases slowly after

smoking cessation. Other risk factors include hypertension and male sex. In the U.S., the incidence of

AAA is 2-4% in the adult population.. AAA is 4-6 times more common in male siblings of known

patients, with a risk of 20-30%.

Rupture of the AAA occurs in 1-3% of men aged 65 or more, the mortality is 70-95%.

Classification

Thoracic aortic aneurysms are found on the thoracic aorta; these are further classified

as ascending, aortic arch, or descendinganeurysms depending on the location on the thoracic aorta

involved.

Abdominal aortic aneurysms, the most common form of aortic aneurysm, are found on

the abdominal aorta, and thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysms involve both the thoracic and

abdominal aorta.

Popliteal: an aneurysm in the artery behind the knee

Renal: an aneurysm in the kidney; a very rare condition

Visceral: an aneurysm in an internal organ and/or intestines

Etiology

Congenital: primary connective tissue disorders (Marfans syndrome, Ehlers- Danlos syndrome) and

other diseases (focal medical agenesis, tuberous sclerosis, Turnersr syndrome, Menkes syndrome)

Mechanical (hemodynamic): Poststenotic and arteriovenous fistula and amputation related.

Traumatic (pseudoaneurysms): Penetrating arterial injuries, blunt arterial injuries

Inflammatory (noninfectious): Associated with arteritis (Takayasus dse, giant cell arteritis, SLE,

Behcets syndrome, Kawasakis dse) and periarterial inflammation (i.e pancreatitis)

Infectious (mycotic): Bacterial, Fungal, Spirochetal infections

Pregnancy related degenerative: Nonspecific, inflammatory variant

Anastomotic (postartetiotomy) and graft aneurysms: infection, arterial wall failure, suture failure,

graft failure

Manifestations

Symptoms of a thoracic aortic aneurysm (affecting upper part of aorta in chest):

y Pain in the jaw, neck, upper back or chest

y Coughing, hoarseness or difficulty breathing, stridor, aphonia, dysphagia

Symptoms of an abdominal aortic aneurysm (affecting lower part of aorta in abdomen):

y Pulsating enlargement or tender mass felt by a physician when performing a physical examination

y Pain in the back, abdomen, or groin not relieved with position change or pain medication

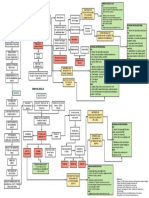

Diagnostics

y Chest x-ray

y Computed tomography (CT) scan

y Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

y Echocardiography (an ultrasound of the heart) / TEE

y Abdominal ultrasound (to look for associated abdominal aneurysms)

y Angiography (an x-ray of the blood vessels)

Treatment

Medical

Statin (or cholesterol lowering medication) to maintain the health of your blood vessels.

Controlling BP (systolic pressure maintained at 100 120 mmHg)

Antihypertensive : hydralazine (Apresoline)

Beta blocker : esmolol (Brevibloc), metoprolol (Lopressor)

IV drip: Sodium nitroprusside (Nipride)

watchful waiting. By closely monitoring your condition with CT or MRI scans every 6-12

months, the aneurysm will be watched for signs of changes.

Surgical

Endovascular graft

Endovascular repair

endoluminal exclusion

Nursing Care

1. Ineffective health maintenance

Interventions:

a. Assess level of clients cognitive, emotional, physical functioning.

b. Note clients age

c. Note desire/ level of ability to meet health maintenance needs, as well as self-care ADLs.

d. Assess clients ability and desire to learn.

e. Encourage socialization and personal involvement

f. Assist client to develop stress management skills

2. Fear/Anxiety related to lack of understanding of diagnostic tests, surgical

procedure, and postoperative care.

Interventions:

g. Orient client to critical care unit if appropriate.

h. Describe and explain the rationale for equipment and tubes that may present

postoperatively. (e.g., cardiac monitor, ventilator, intravenous and intra-arterial lines,

NGT, urinary catheter)

i. Reinforce physicians explanations and clarify misconceptions client has about effects of

the surgery on sexual functioning

3. Risk for imbalanced fluids and electrolytes

Interventions:

a. Note potential sources of fluid loss/intake.

b. Note clients age, current level of hydration, and mentation.

c. Review laboratory data

d. Measure and record intake and output.

e. Weigh daily

f. Auscultate BP, calculate pulse pressure. (pulse pressure widens before systolic BP drops

in response to fluid loss.)

You might also like

- 8 Sample Care Plans For ACDFDocument11 pages8 Sample Care Plans For ACDFacasulla98No ratings yet

- Nursing Care Plan: Risk For Disuse SyndromeDocument2 pagesNursing Care Plan: Risk For Disuse SyndromeRozsy FakhrurNo ratings yet

- Cathlab Manual Coronary AngiographyDocument28 pagesCathlab Manual Coronary AngiographyNavojit Chowdhury100% (5)

- Concept Map HypertensionDocument1 pageConcept Map Hypertensiongeorge pearson0% (1)

- Brain Over BodyDocument10 pagesBrain Over BodyJohn LenoNo ratings yet

- FETAL ECHOCARDIOGRAPHY PPT DD Fix2Document43 pagesFETAL ECHOCARDIOGRAPHY PPT DD Fix2PAOGI UNAND100% (1)

- Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm and Atherosclerosis FINALDocument23 pagesAbdominal Aortic Aneurysm and Atherosclerosis FINALErica P. ManlunasNo ratings yet

- Sepsis Is The Consequence of A Dysregulated Inflammatory Response To An Infectious InsultDocument11 pagesSepsis Is The Consequence of A Dysregulated Inflammatory Response To An Infectious InsultShrests SinhaNo ratings yet

- Coronary Artery DiseaseDocument3 pagesCoronary Artery Diseasetrew_wertNo ratings yet

- Cva Concept MapDocument1 pageCva Concept MapAnn Justine OrbetaNo ratings yet

- Care Plan For Excess Fluid Volume ExampleDocument3 pagesCare Plan For Excess Fluid Volume ExampleVette Angelikka Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- Peripheral Arterial Occlusive DiseaseDocument4 pagesPeripheral Arterial Occlusive Diseasekrisfred14100% (1)

- Concept Map (Aplastic Anemia) b1Document6 pagesConcept Map (Aplastic Anemia) b1Ran PioloNo ratings yet

- Generic (Trade Name) Dosage / Frequency Classification Indication Contraindication Side Effects Nsg. ResponsibilitiesDocument4 pagesGeneric (Trade Name) Dosage / Frequency Classification Indication Contraindication Side Effects Nsg. Responsibilitiesliesel_12100% (1)

- Coreg (Carvedilol)Document3 pagesCoreg (Carvedilol)ENo ratings yet

- Risk For Falls Aeb Loss of BalanceDocument4 pagesRisk For Falls Aeb Loss of BalanceAlexandrea MayNo ratings yet

- Atracurium BesylateDocument3 pagesAtracurium BesylateWidya WidyariniNo ratings yet

- HCVDDocument5 pagesHCVDkhrizaleehNo ratings yet

- © 2020 Lippincott Advisor Nursing Care Plans For Medical Diagnoses - Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID 19) PDFDocument7 pages© 2020 Lippincott Advisor Nursing Care Plans For Medical Diagnoses - Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID 19) PDFVette Angelikka Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- Impaired Physical Mobility R/T Neuromuscular ImpairmentDocument3 pagesImpaired Physical Mobility R/T Neuromuscular ImpairmentjisooNo ratings yet

- NCPDocument9 pagesNCPKarell Eunice Estrellado Gutierrez100% (1)

- NCP Self Care DeficitDocument3 pagesNCP Self Care DeficitLeizel ApolonioNo ratings yet

- Raynaud's DISEASEDocument3 pagesRaynaud's DISEASEkondame aisheeNo ratings yet

- Disseminated Intravascular CoagulationDocument8 pagesDisseminated Intravascular CoagulationMade NoprianthaNo ratings yet

- TAHBSO ReportDocument4 pagesTAHBSO ReportsachiiMeNo ratings yet

- NCP For BreathingDocument17 pagesNCP For BreathingCeleste Sin Yee100% (1)

- Drug Study - CholangioDocument10 pagesDrug Study - CholangioClaireMutiaNo ratings yet

- Intussusception: PathophysiologyDocument8 pagesIntussusception: PathophysiologyNaufal AndaluNo ratings yet

- Constipation NCPDocument2 pagesConstipation NCPKaren Pili100% (1)

- Urinary Tract Infection, (UTI) Is An Infection of One orDocument4 pagesUrinary Tract Infection, (UTI) Is An Infection of One orLorebellNo ratings yet

- NCP Angina Coronary Artery DiseaseDocument6 pagesNCP Angina Coronary Artery DiseaseRon Batacan De LeonNo ratings yet

- Heart Failure COncept MapDocument2 pagesHeart Failure COncept MapJrBong SemaneroNo ratings yet

- Impaired Physical Mobility. Impaired CommunicationDocument5 pagesImpaired Physical Mobility. Impaired CommunicationJovania Liza R. Baguilat100% (2)

- Case Study - ESRD (DS, NCP)Document8 pagesCase Study - ESRD (DS, NCP)Zhy CaluzaNo ratings yet

- Ineffective Tissue Perfusion PDFDocument4 pagesIneffective Tissue Perfusion PDFgcodouganNo ratings yet

- CHF Concept MapDocument1 pageCHF Concept MapChristy Wegner Cooper100% (4)

- Cerebrovascular AccidentDocument8 pagesCerebrovascular Accidentplethoraldork100% (10)

- Drug PrilosecDocument1 pageDrug PrilosecSrkocher100% (1)

- HyponatremiaDocument6 pagesHyponatremiaJaymart Saclolo CostillasNo ratings yet

- Drug Study (AFP)Document10 pagesDrug Study (AFP)Summer SuarezNo ratings yet

- Concept Map FinalDocument1 pageConcept Map Finalapi-383763177No ratings yet

- Urosepsis 1Document7 pagesUrosepsis 1Anonymous Xajh4w100% (1)

- Angina Pectoris PathophysiologyDocument2 pagesAngina Pectoris PathophysiologyALIANA KIMBERLY MALQUESTONo ratings yet

- Nursing Care Plans For Activity IntoleranceDocument4 pagesNursing Care Plans For Activity IntolerancethebigtwirpNo ratings yet

- Drug StudyDocument3 pagesDrug StudyKorina FranciscoNo ratings yet

- Drug StudyDocument5 pagesDrug StudyDick Morgan FerrerNo ratings yet

- Care of The Mother, Child at Risk or With Problems (Acute and Chronic)Document6 pagesCare of The Mother, Child at Risk or With Problems (Acute and Chronic)Elizabeth ZamoraNo ratings yet

- Stoke Pathophysiology 1228539935337551 8Document7 pagesStoke Pathophysiology 1228539935337551 8Mark Anthony Taña GabiosaNo ratings yet

- AmiodaroneDocument2 pagesAmiodaronekumaninaNo ratings yet

- Drug Study On DOPAMINEDocument5 pagesDrug Study On DOPAMINEshadow gonzalezNo ratings yet

- As Needed.: Environmental Stimuli 6Document4 pagesAs Needed.: Environmental Stimuli 6Nicole GumolonNo ratings yet

- Drug StudyDocument20 pagesDrug StudydjanindNo ratings yet

- HEMARATE FA Hemarate FA Consists of Folic AcidDocument2 pagesHEMARATE FA Hemarate FA Consists of Folic AcidMarhina Asarabi MukimNo ratings yet

- Growth and DevelopmentDocument5 pagesGrowth and DevelopmentGabrielLopezNo ratings yet

- NCP Tissue PerfusionDocument3 pagesNCP Tissue PerfusionKat Brija100% (1)

- Gastroschisis & OmphaloceleDocument1 pageGastroschisis & OmphaloceleMaecy PasionNo ratings yet

- P 398Document1 pageP 398Arup Ratan PaulNo ratings yet

- Medical Ward Drug StudyDocument9 pagesMedical Ward Drug StudygorgeazNo ratings yet

- Assessment Nursing Diagnosis Planning Intervention Rationale EvaluationDocument4 pagesAssessment Nursing Diagnosis Planning Intervention Rationale EvaluationMara Jon Ocden CasibenNo ratings yet

- Disorders of Arterial Circulation - 8Document42 pagesDisorders of Arterial Circulation - 8Cres Padua QuinzonNo ratings yet

- Aortic Aneurysm: Imu LectureDocument73 pagesAortic Aneurysm: Imu LectureCeline HerreraNo ratings yet

- Vascular Sugergy Questions NasirDocument19 pagesVascular Sugergy Questions NasirAhmad SobihNo ratings yet

- Adobe Scan 13 May 2021Document5 pagesAdobe Scan 13 May 2021Harisree SNo ratings yet

- Medical Terminology LicentaDocument75 pagesMedical Terminology LicentaGabriel BarbarasaNo ratings yet

- Pericardial Disease 1Document100 pagesPericardial Disease 1Anab Mohamed Elhassan Abbas AlnowNo ratings yet

- Total Artificial Heart: Surgical Technique in The Patient With Normal Cardiac AnatomyDocument7 pagesTotal Artificial Heart: Surgical Technique in The Patient With Normal Cardiac AnatomyDoraemon BiruNo ratings yet

- Biol 328 Fall 2018 Lab Manual Part 2 (Labs 10-14)Document134 pagesBiol 328 Fall 2018 Lab Manual Part 2 (Labs 10-14)Lisa WolskiNo ratings yet

- Anatomy and Physiology of The Cardiovascular System Functions of The HeartDocument3 pagesAnatomy and Physiology of The Cardiovascular System Functions of The HeartPeej ReyesNo ratings yet

- Aortopulmonary Window in InfantsDocument3 pagesAortopulmonary Window in Infantsonlyjust4meNo ratings yet

- RN Expert Guides Cardiovascular Care PDFDocument512 pagesRN Expert Guides Cardiovascular Care PDFSteven Berschaminski100% (1)

- (Compana) Comparative Anatomy of The Circular SystemDocument11 pages(Compana) Comparative Anatomy of The Circular SystemTherese Claire Marie JarciaNo ratings yet

- Embryology of The Heart and The Great VesselsDocument66 pagesEmbryology of The Heart and The Great VesselsNavya HegdeNo ratings yet

- Circulatory SystemDocument16 pagesCirculatory SystemHarinder KaurNo ratings yet

- Anatomy of The Cardiovascular SystemDocument75 pagesAnatomy of The Cardiovascular SystemM RazzaqNo ratings yet

- Day 1 Ple Practice Exam Week 2: BiochemistryDocument8 pagesDay 1 Ple Practice Exam Week 2: BiochemistrySanielle Karla Garcia LorenzoNo ratings yet

- CV Examples PDFDocument5 pagesCV Examples PDFAsp Corp SlaveNo ratings yet

- Anatomy SharkDocument32 pagesAnatomy SharkKanwal RashidNo ratings yet

- CH 20 CVS - Physiology and Anatomy NotesDocument50 pagesCH 20 CVS - Physiology and Anatomy NotesSafa AamirNo ratings yet

- DNB Question BankDocument31 pagesDNB Question BankPrakash SapkaleNo ratings yet

- Regulation of BPDocument55 pagesRegulation of BPsultan khabeebNo ratings yet

- Ouriel K., Rutherford R.В. - Atlas of Vascular Surgery - Basic Techniques and Exposures - ocrDocument270 pagesOuriel K., Rutherford R.В. - Atlas of Vascular Surgery - Basic Techniques and Exposures - ocr.No ratings yet

- 10 - FN 14 CVS Anatomy IntroDocument15 pages10 - FN 14 CVS Anatomy IntroCamille GrefaldiaNo ratings yet

- 5 Cardiovascular DisordersDocument4 pages5 Cardiovascular DisordersChristian Joseph OpianaNo ratings yet

- Activity 5: Cardiovascular SystemDocument29 pagesActivity 5: Cardiovascular SystemDenmarc AranasNo ratings yet

- Abd AortaDocument48 pagesAbd AortaSanjib NepramNo ratings yet

- U6C6 - Carty Soriano - Heart ValvesDocument6 pagesU6C6 - Carty Soriano - Heart ValvesXio LinaresNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Aortic RegurgitationDocument8 pagesAssessment of Aortic RegurgitationKhurram NadeemNo ratings yet

- EACVI CCT Core SyllabusDocument13 pagesEACVI CCT Core SyllabushgadNo ratings yet

- Anatomy (Marian Diamond)Document34 pagesAnatomy (Marian Diamond)NHZANo ratings yet