Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Society For American Archaeology

Society For American Archaeology

Uploaded by

diogborges0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

7 views4 pages...

Original Title

Schiffer 99

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Document...

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

7 views4 pagesSociety For American Archaeology

Society For American Archaeology

Uploaded by

diogborges...

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 4

Society for American Archaeology

Behavioral Archaeology: Some Clarifications

Author(s): Michael Brian Schiffer

Reviewed work(s):

Source: American Antiquity, Vol. 64, No. 1 (Jan., 1999), pp. 166-168

Published by: Society for American Archaeology

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2694352 .

Accessed: 20/05/2012 14:59

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Society for American Archaeology is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

American Antiquity.

http://www.jstor.org

BEHAVIORAL ARCHAEOLOGY: SOME CLARIFICATIONS

Michael Brian Schiffer

In their comment on Schiffer (1996), Broughton and O'Connell perpetuate several commion misconceptions about behavioral

archaeology. This brief reply clarifies the character and goals of behavioral archaeology and indicates that this vigorous pro-

gram is now beginning to produce "social" theory beyond the explanation of variability in artifact designs.

En sit commentario sobre Schiffer (1996) Broughton y O'Connel (1998) perpettian varios malentendidos comnunes sobre la arqule-

ologia conductal e indica que sit vigoroso programa estd empezando a producir teoria "social" que va mids alld de la explicaci6n

de variabilidad en el disenio de artefactos.

J am delighted that Broughton and O'Connell

have reacted so constructively to my experi-

ment in archaeological communication. Adding

evolutionary ecology to the programs under discus-

sion should have a salutory effect by bringing in

other voices and views. In response to Broughton

and O'Connell's piece, my points are few but not

unimportant.

I agree with virtually the entirety of Broughton

and O'Connell's comments about selectionist

archaeology, but I must take issue with some of

their statements about the behavioral program.

Broughton and O'Connell perpetuate several mis-

conceptions about behavioral archaeology that are

regrettably prevalent in the discipline.

Perhaps most seriously, they misconstrue behav-

ioral archaeology's character and goals. They claim

that the program's goals are "to reconstruct and

explain variation in past human behavior" (empha-

sis in original). In fact, none of the five publications

they cite for this statement supports it. The first

(Schiffer 1972) makes no mention of "behavioral

archaeology," much less its goals. The second

(Schiffer 1976) does not speak of goals per se, but

offers behavioral archaeology as "the particular

configuration of principles, activities, and interests

that we offer to reintegrate the discipline" (Schiffer

1995a:69, orig. 1976). We also made clear behav-

ioral archaeology's unique conception of the disci-

pline's subject matter, which is not confined to the

past but encompasses "the relationships between

human behavior and material culture in all times

and all places (Schiffer 1995a:69, orig. 1976;

emphasis added). This crucial phrase captures the

core of behavioral archaeology. Citations three and

four (Schiffer 1983, 1987) are about formation

processes and do not deal explicitly with behavioral

archaeology. However, Schiffer (1987:4) does reit-

erate that archaeology's subject matter-"human

behavior and material culture"-has no spatial or

temporal boundaries. Fifth, and finally, Schiffer

(1995a:23) again states that behavioral archaeology

is about people-artifact relationships in all times

and places, and emphasizes the behavioralists' con-

ceptualization of archaeology as a unique scientific

enterprise having "ambitious goals."

Ironically, in the paper that stimulated

Broughton and O'Connell's comment (Schiffer

1996) lies this succinct statement: "Behavioralists

seek to explain variability and change in human

behavior by emphasizing the study of relationships

between people and their artifacts" (Schiffer

1996:644). Thus, behavioral archaeology's goals

are the broad goals of the social and behavioral sci-

ences, but they entail a unique focus on people-arti-

fact interactions regardless of time or space.

Broughton and O'Connell recognize that the

behavioralists' first task, as archaeologists, was to

provide a firm foundation for establishing infer-

ences from the archaeological record. Thus, we

Michael Brian Schiffer * Department of Anthropology, University of Arizona, Tucson AZ 85721

American Antiquity, 64(1), 1999, pp. 166-168

Copyright ? 1999 by the Society for American Archaeology

166

COEMENTSN1 7

have supplied conceptual tools for creating a

behavioral past: new models of inference (e.g.,

Dean 1978; Schiffer 1976, Chapter 2; Sullivan

1978) along with innumerable principles (produced

by experimental archaeologists and ethnoarchaeol-

ogists), many of which are employed for coping

with variability that formation processes intro-

duced into the archaeological and historical

records. Arguably, the improvement of inference

has been behavioral archaeology's major contribu-

tion to the discipline thus far.

Broughton and O'Connell also acknowledge

that behavioral archaeologists recently have begun

to address explanatory questions, focusing on "arti-

fact design," claiming that "The basic expectation

is that design will be 'optimal' with respect to func-

tion." Although the word optimal does appear in

Schiffer and Skibo (1987), we renounced its use in

the same issue of Current Anthropology when

replying to the commentators, and I have not used

"optimal" as a technical term since. Moreover, in

our most recent paper (Schiffer and Skibo 1997),

which is a fully general theory of artifact design,

we have framed the problem in a way that obviates

any preconceptions about optimality. In that effort,

we urge investigators to attend to the diverse behav-

ioral and social factors that affect the artisan's

weighting of performance characteristics-

mechanical, thermal, visual, acoustic, etc.-in any

specific artifact's design. Whether a given artifact

design "optimizes" a given performance character-

istic or characteristics is always an empirical ques-

tion. We also advocate abandoning the terms style

and function because they are too imprecise for sci-

entific work. Apparently, Broughton and

O'Connell have adopted McGuire's (1995) carica-

ture of our approach to explaining artifact design

rather than closely reading our recent theoretical

statements and case studies (e.g., Schiffer 1991;

Schiffer et al. 1994).

Like others before them, Broughton and

O'Connell fault behavioral archaeology for lack-

ing "a general body of theory, applicable to any

hominid, that produces testable hypotheses about

the relationship between relevant ecological vari-

ables and specific forms of behavior and morphol-

ogy." They believe that evolutionary ecology

uniquely provides such theory. Before clarifying

the behavioralists' approach to building "general,"

"explanatory," or "social" theory, I briefly examine

Broughton and O'Connell's claim that evolution-

ary ecology is the answer to all of our theoretical

questions.

Evolutionary ecology has valuable formulations

to contribute to the mix of models and theories

needed for explaining the entire range of behavioral

variability and change that interests archaeologists.

But evolutionary ecology, like selectionism, post-

processualism, and behavioral archaeology, lacks

the theories required to answer our every question.

Given the wide range of current questions, we must

acknowledge that theories from diverse programs

are needed to help answer them. For example, if I

wanted to explain variability in institutional ideolo-

gies in complex societies, I would first turn for

insights to Marxist theorists. Similarly, if I were

interested in explaining the sources of variability in

a specific technology, I would draw upon behav-

ioral theory and models. And, if I suddenly had a

yen to explain hunting behaviors in a foraging soci-

ety, I would immediately bone up on evolutionary

ecology. No theoretical program in archaeology-

or elsewhere in the sciences-is comprehensive

when it comes to explaining variability and change

in human behavior. It strikes me as little more than

wishful thinking to believe that any program now

possesses theories that can explain more than a tiny

fraction of the totality of human behavioral vari-

ability.

Preoccupied for more than two decades with

putting archaeological inference on a scientific

footing, some behavioral archaeologists, including

this author, have acknowledged in the past few

years the need to devote more effort to building

"social" theories (sensu Schiffer 1988). Behavioral

archaeologists assert that our focus-the archaeo-

logical focus-on people-artifact interactions

establishes a new and unique perspective for build-

ing social theory (Schiffer 1995b:23).

Neither in the social sciences, nor in the life sci-

ences, nor in the physical sciences have investiga-

tors erected theory upon an ontology that

recognizes the reality of human existence: our

incessant and diverse interactions with myriad

things (Schiffer 1995b, 1999a; Walker et al. 1995).

Behavioralists merely claim that this ontology,

along with countless behavioral models (such as

life-history models pertaining to people, artifacts,

places, behavioral components, etc.-e.g.,

LaMotta and Schiffer 1999; Rathje and Schiffer

168 AMERICAN ANTIQUITY [Vol.

64,

No.

1, 1999]

1982; Schiffer 1976, 1995a, 1995b, 1996; Walker

1995, 1998; Zedefio 1997), provides a springboard

for constructing new social theory. Broughton and

O'Connell imply that behavioral archaeology has a

reduced potential to generate social theory in com-

parision to evolutionary ecology and, presumably,

other programs. However, as the above citations

indicate, our theory-building efforts now go well

beyond the explanation of artifact design (see also

Schiffer 1992, Chapters 4-7). And, more recently,

behavioralists have offered a theory of meaning

(Schiffer and Miller 1999b) and a general theory of

communication (Schiffer and Miller 1999a).

Moreover, many archaeologists who do not self-

identify as behavioralists, including some post-

processualists and evolutionary ecologists, are

contributing to the development of diverse theories

compatible with the behavioral program (e.g.,

Hayden 1998; Thomas 1996). It is precisely this

broadening front of theory-building efforts, not

abstract pronouncements from advocates of other

programs, that will define the boundaries of behav-

ioral archaeology's applicability.

Unlike evolutionary ecologists, selectionists,

and many postprocessualists, behavioralists do not

believe that off-the-shelf theories from other disci-

plines furnish answers to every explanatory ques-

tion. Behavioralists advocate a new ontology for

constructing social theory that privileges the inves-

tigation of people-artifact relationships in all times

and places. Upon the diligent study of these rela-

tionships behavioral archaeologists-and many

others-are quietly constructing new theories of

human behavior, bringing to fruition my early

vision of archaeology as a rather special behavioral

science having extraordinary potential (Schiffer

1975).

References Cited

Dean, J. S.

1978 Independent Dating in Archaeological Analysis.

Advances in Archaeological Method and Theoty

1:223-255.

Hayden, B.

1998 Practical and Prestige Technologies: The Evolution of

Material Systems. Journal of Archaeological Method and

Theory 5:1-55.

LaMotta, V. M., and M. B. Schiffer

1999 Fornation Processes of House Floor Assemblages. In

The Archaeology of Household Activities, edited by P.

Allison. Routledge, London.

McGuire, R. H.

1995 Behavioral Archaeology: Reflections of a Prodigal

Son. In Expanding Archaeology, edited by J. M. Skibo, W.

H. Walker, and A. E. Nielsen, pp. 162-177. University of

Utah Press, Salt Lake City.

Rathje, W. L., and M. B. Schiffer

1982 Archaeology. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, New York.

Schiffer, M. B.

1972 Archaeological Context and Systemic Context.

Anmerican Antiquity 37:156-165.

1975 Archaeology as Behavioral Science. Americacn

Anthropologist 77:836-848.

1976 Behavioral Archeology. Academic Press, New York.

1983 Toward the Identification of Formation Processes.

American Antiquity 48:675-706.

1987 Formation Processes of the Archaeological Record.

University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque.

1988 The Structure of Archaeological Theory. American

Antiquity 53:461-485.

1991 The Portable Radio in American Life. University of

Arizona Press, Tucson.

1992 Technological Perspectives on Behavioral Change.

University of Arizona Press, Tucson.

1995a Behavioral Archaeology:First Principles. University

of Utah Press, Salt Lake City.

1995b Social Theory and History in Behavioral

Archaeology. In Expanding Archaeology, edited by J. M.

Skibo, W. H. Walker, and A. E. Nielsen, pp. 22-35.

University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City.

1996 Some Relationships Between Behavioral and

Evolutionary Archaeologies. American Antiquity

61:643-662.

Schiffer, M. B., T. C. Butts, and K. Grimm

1994 Taking Charge: The Electric Automobile in America.

Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D. C.

Schiffer, M. B., and A. R. Miller

1999a Beyond Language. Artifacts, Behaviot; and

Commitunication. Routledge, London.

1999b A Behavioral Theory of Meaning. In Pottery and

People, edited by J. M. Skibo and G. Feinman. University

of Utah Press, Salt Lake City.

Schiffer, M. B., and J. M. Skibo

1987 Theory and Experiment in the Study of Technological

Change. Current Anthropology 28:595-622.

1997 The Explanation of Artifact Variability. American

Antiquity 62:27-50.

Sullivan, A. P.

1978 Inference and Evidence: A Discussion of the

Conceptual Problems. Advances in A rchaeological Method

and Theory 1:183-222.

Thomas, J.

1996 Time, Culture, and Identity. Routledge, London.

Walker, W. H.

1995 Ceremonial Trash? In Expanding Archaeology, edited

by J. M. Skibo, W. H. Walker, and A. E. Nielsen, pp. 1-12.

University of Utah Press, Salt Lake City.

1998 Where are the Witches of Prehistory? Journal of

Archaeological Method and Theoty 5:245-308.

Walker, W. H., J. M. Skibo, and A. E. Nielsen

1995 Introduction: Expanding Archaeology. In Expanding

Archaeology, edited by J. M. Skibo, W. H. Walker, and A.

E. Nielsen, pp. 1-12. University of Utah Press, Salt Lake

City.

Zedefio, M.N.

1997 Landscapes, Land Use, and the History of Territoiy

Formation: An Example from the Puebloan Southwest.

Journal of Archaeological Method and Theoty 4:67-103.

Received July 1, 1998; accepted July 21, 1998

You might also like

- Widukind - Deeds of The SaxonsDocument174 pagesWidukind - Deeds of The SaxonsStan ArianaNo ratings yet

- WOBST 1977 Stylistic Behaviour and Information Exchange PDFDocument14 pagesWOBST 1977 Stylistic Behaviour and Information Exchange PDFChristian De AndradeNo ratings yet

- Test-Taking Strategy HughesDocument11 pagesTest-Taking Strategy Hughesapi-296486183No ratings yet

- Human Capital: Education and Health in Economic DevelopmentDocument33 pagesHuman Capital: Education and Health in Economic DevelopmentIvan PachecoNo ratings yet

- Dietler y Herbich 1998Document16 pagesDietler y Herbich 1998Vikitty RuizNo ratings yet

- Archaeological Evidence For The Emergence of Language, Symbolism, and Music-An Alternative Multidisciplinary PerspectiveDocument70 pagesArchaeological Evidence For The Emergence of Language, Symbolism, and Music-An Alternative Multidisciplinary Perspectivemilosmou100% (1)

- Paper - Prehistoric Archaeology and Cognitive Anthropology A Review PDFDocument18 pagesPaper - Prehistoric Archaeology and Cognitive Anthropology A Review PDFFrancisco Fernandez OrdieresNo ratings yet

- Archaeology Book Collection 2016 PDFDocument30 pagesArchaeology Book Collection 2016 PDFAung Htun LinnNo ratings yet

- Archaeological Classification: Theory Versus Practice: William Y. AdamsDocument17 pagesArchaeological Classification: Theory Versus Practice: William Y. AdamsmehdaiNo ratings yet

- Hillson 1979Document21 pagesHillson 1979Lu MilleNo ratings yet

- The KW Fort Mill Passport To SuccessDocument29 pagesThe KW Fort Mill Passport To SuccessCarissa DixonNo ratings yet

- Armelagos Et Al. A Century of Skeletal PathologyDocument13 pagesArmelagos Et Al. A Century of Skeletal PathologylaurajuanarroyoNo ratings yet

- The Life of An Artifact: Introduction: Interpretive Archaeology - An Oblique PerspectiveDocument27 pagesThe Life of An Artifact: Introduction: Interpretive Archaeology - An Oblique PerspectiveMauro FernandezNo ratings yet

- Chang, Kwang-Chih. 1967. Major Aspects of The Interrelationship of Archaeology and Ethnology.Document18 pagesChang, Kwang-Chih. 1967. Major Aspects of The Interrelationship of Archaeology and Ethnology.MelchiorNo ratings yet

- Spatial Analysis of Bakun Period Settlements in Kazeroun and Nurabad Mamasani Counties in Fars Province, Southern IranDocument8 pagesSpatial Analysis of Bakun Period Settlements in Kazeroun and Nurabad Mamasani Counties in Fars Province, Southern IranTI Journals PublishingNo ratings yet

- ODELL, G. Stone Tool Research at The End of The Millennium Classification, Function, and Behavior. 2001Document56 pagesODELL, G. Stone Tool Research at The End of The Millennium Classification, Function, and Behavior. 2001marceNo ratings yet

- Knusel, C. J., 2009. Bioarchaeology A Synthetic ApproachDocument13 pagesKnusel, C. J., 2009. Bioarchaeology A Synthetic ApproachĐani NovakovićNo ratings yet

- Binford 1979 Organization andDocument20 pagesBinford 1979 Organization andisnardisNo ratings yet

- 01 Basic Concepts in ArchaeologyDocument66 pages01 Basic Concepts in ArchaeologyHannah Dodds100% (1)

- Anschuetz, K - Archaeology of Landscapes, Perspectives and DirectionsDocument55 pagesAnschuetz, K - Archaeology of Landscapes, Perspectives and Directionsmaster_ashNo ratings yet

- Field Archaeology DevelopmentDocument9 pagesField Archaeology DevelopmentKrisha DesaiNo ratings yet

- Ancient DNA, Strontium IsotopesDocument6 pagesAncient DNA, Strontium IsotopesPetar B. BogunovicNo ratings yet

- The Emergence of Ornaments and Art-An Archaeological Perspective On The Origins of Behavioral Modernity JoãoDocument55 pagesThe Emergence of Ornaments and Art-An Archaeological Perspective On The Origins of Behavioral Modernity JoãosakunikaNo ratings yet

- Archaeology: Spatial Analysis in Archaeology. Ian Hodder and Clive OrtonDocument3 pagesArchaeology: Spatial Analysis in Archaeology. Ian Hodder and Clive OrtonjackNo ratings yet

- ConceptualIssues and Environmental ArchaeologyDocument322 pagesConceptualIssues and Environmental ArchaeologyIoana MărinceanNo ratings yet

- Hurt&Rakita - Style and Function Conceptual Issues in Evolutionary Archaeology PDFDocument240 pagesHurt&Rakita - Style and Function Conceptual Issues in Evolutionary Archaeology PDFDiana Rocio Carvajal ContrerasNo ratings yet

- Corfield, N. y Williams, J. Preservation of Archaeological Remains in Situ. 2011Document7 pagesCorfield, N. y Williams, J. Preservation of Archaeological Remains in Situ. 2011Trinidad Pasíes Arqueología-ConservaciónNo ratings yet

- Settlement and Landscape Archaeology: Gary M Feinman, The Field Museum, Chicago, IL, USADocument5 pagesSettlement and Landscape Archaeology: Gary M Feinman, The Field Museum, Chicago, IL, USAarmando nicolau romero100% (1)

- Painter - "Territory-Network"Document39 pagesPainter - "Territory-Network"c406400100% (1)

- World Archaeology: Archaeological' MethodDocument17 pagesWorld Archaeology: Archaeological' MethodSharada CVNo ratings yet

- O'Hara MADocument194 pagesO'Hara MAfmohara3No ratings yet

- Zedeño - The Archaeology of Territory and Territoriality (Arqueologia) PDFDocument8 pagesZedeño - The Archaeology of Territory and Territoriality (Arqueologia) PDFPaulo Marins GomesNo ratings yet

- Arch of Entanglement ProofsDocument256 pagesArch of Entanglement Proofscarlos miguel angel carrasco100% (1)

- BINFORD - Mobility, Housing, and Environment, A Comparative StudyDocument35 pagesBINFORD - Mobility, Housing, and Environment, A Comparative StudyExakt NeutralNo ratings yet

- Postprocessual Archaeology - OriginsDocument6 pagesPostprocessual Archaeology - Originsihsan7713No ratings yet

- (P) Behrensmeyer, A. (1978) - Taphonomic and Ecologic Information From Bone WeatheringDocument14 pages(P) Behrensmeyer, A. (1978) - Taphonomic and Ecologic Information From Bone WeatheringSara BrauerNo ratings yet

- Turpin (1990) Rock Art and Hunter-Gatherer ArchaeologyDocument20 pagesTurpin (1990) Rock Art and Hunter-Gatherer ArchaeologyRob BotelloNo ratings yet

- Krieger 1944Document19 pagesKrieger 1944Héctor Cardona MachadoNo ratings yet

- Why ExcavateDocument55 pagesWhy ExcavateMartin ČechuraNo ratings yet

- Choyke, Schibler - Prehistoric Bone Tools and The Archaeozoological PerspectiveDocument15 pagesChoyke, Schibler - Prehistoric Bone Tools and The Archaeozoological PerspectiveRanko ManojlovicNo ratings yet

- Kogalniceanu - Human RemainsDocument46 pagesKogalniceanu - Human RemainsRaluca KogalniceanuNo ratings yet

- 2019 Bioarchaeology and Social Schrader - Activity, Diet and SocialDocument221 pages2019 Bioarchaeology and Social Schrader - Activity, Diet and Socialc.noseNo ratings yet

- Reclaiming Archaeology Introduction PDFDocument47 pagesReclaiming Archaeology Introduction PDFAnonymous L9rLHiDzAHNo ratings yet

- Holtorf-Life History of A Pot SherdDocument24 pagesHoltorf-Life History of A Pot SherdJimena CruzNo ratings yet

- Archaeology in The Making - Lewis Binfor PDFDocument33 pagesArchaeology in The Making - Lewis Binfor PDFLaurita MariitaNo ratings yet

- Palaeopathology: Studying The Origin, Evolution and Frequency of Disease in Human Remains From Archaeological SitesDocument21 pagesPalaeopathology: Studying The Origin, Evolution and Frequency of Disease in Human Remains From Archaeological SitesPutri FitriaNo ratings yet

- Lane 2014 Hunter-Gatherer-Fishers, Ethnoarchaeology, and Analogical ReasoningDocument67 pagesLane 2014 Hunter-Gatherer-Fishers, Ethnoarchaeology, and Analogical ReasoningCamila AndreaNo ratings yet

- Tilley Materiality in Materials 2007Document6 pagesTilley Materiality in Materials 2007Ximena U. OdekerkenNo ratings yet

- Architecture Archaeology and ContemporarDocument154 pagesArchitecture Archaeology and ContemporarBom BomNo ratings yet

- Monitoring Cultural Landscapes From Spac PDFDocument14 pagesMonitoring Cultural Landscapes From Spac PDFFvg Fvg Fvg100% (1)

- Geoarchaeology: Sediments and Site Formation Processes ARCL 2017Document14 pagesGeoarchaeology: Sediments and Site Formation Processes ARCL 2017lady_04_adNo ratings yet

- Surface Collection, Sampling, and Research Design A RetrospectiveDocument18 pagesSurface Collection, Sampling, and Research Design A RetrospectiveKukii Fajardo CardonaNo ratings yet

- On The Past and Contemporary Character of Classical ArchaeologyDocument14 pagesOn The Past and Contemporary Character of Classical ArchaeologyDavid LarssonNo ratings yet

- Coles Experimental Archaeology PDFDocument22 pagesColes Experimental Archaeology PDFEmilyNo ratings yet

- Religion and Material Culture: Matter of BeliefDocument13 pagesReligion and Material Culture: Matter of BeliefrafaelmaronNo ratings yet

- Best Practices For No-Collection Projects and In-Field Analysis in The United StatesDocument8 pagesBest Practices For No-Collection Projects and In-Field Analysis in The United StatesJaime Mujica SallesNo ratings yet

- Foxhall L. - The Running Sands of Time Archaeology and The Short-TermDocument16 pagesFoxhall L. - The Running Sands of Time Archaeology and The Short-TermDuke AlexandruNo ratings yet

- The Neolithic Settlement at Makriyalos, Northern Greece: Preliminary Report On The 1993 - 1995 ExcavationsDocument20 pagesThe Neolithic Settlement at Makriyalos, Northern Greece: Preliminary Report On The 1993 - 1995 ExcavationsDimitra KaiNo ratings yet

- Nature and The Cultural Turn' in Human Geography: Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift April 2008Document35 pagesNature and The Cultural Turn' in Human Geography: Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift April 2008Fajar Setiawan YulianoNo ratings yet

- MILNER, N. y P. MIRACLE (Eds.) - Consuming Passions and Patterns of Consumption. 2002 PDFDocument144 pagesMILNER, N. y P. MIRACLE (Eds.) - Consuming Passions and Patterns of Consumption. 2002 PDFPhool Rojas CusiNo ratings yet

- The Impossible Coincidence. A Single-Species Model For The Origins of Modern Human Behavior in EuropeDocument16 pagesThe Impossible Coincidence. A Single-Species Model For The Origins of Modern Human Behavior in EuropeMonica RachisanNo ratings yet

- Civilised by beasts: Animals and urban change in nineteenth-century DublinFrom EverandCivilised by beasts: Animals and urban change in nineteenth-century DublinNo ratings yet

- Movimientos Politicos AfroecuatorianosDocument154 pagesMovimientos Politicos AfroecuatorianosProfe ViníciusNo ratings yet

- Chavin12 LRDocument19 pagesChavin12 LRDiogo BorgesNo ratings yet

- Archaeological Systematics and The Study of Cultural Processes (1967)Document9 pagesArchaeological Systematics and The Study of Cultural Processes (1967)Marcel LopesNo ratings yet

- KOHL, P. Limits To A Post-Processual Archaeology. 1993Document7 pagesKOHL, P. Limits To A Post-Processual Archaeology. 1993Diogo BorgesNo ratings yet

- Schiffer 72Document11 pagesSchiffer 72Diogo BorgesNo ratings yet

- 1ps0 May 2020 Paper 1 QP Edexcel Gcse PsychologyDocument40 pages1ps0 May 2020 Paper 1 QP Edexcel Gcse PsychologyFalahath JayranNo ratings yet

- The Central Conception of BuddhismDocument60 pagesThe Central Conception of Buddhismkala01100% (1)

- Caed 100-Career Education and Personality DevelopmentDocument46 pagesCaed 100-Career Education and Personality DevelopmentRogelyn RendoqueNo ratings yet

- Adhd Case StudyDocument12 pagesAdhd Case StudySupDrNo ratings yet

- BE SOMEONE'S AGE (Phrase) Definition and Synonyms - Macmillan DictionaryDocument3 pagesBE SOMEONE'S AGE (Phrase) Definition and Synonyms - Macmillan DictionaryZahid5391No ratings yet

- Cba GuidelinesDocument4 pagesCba Guidelines2057010260No ratings yet

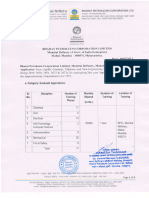

- BPCL NotificationDocument5 pagesBPCL Notificationd mNo ratings yet

- AR ThesesDocument15 pagesAR Thesestoyi kamiNo ratings yet

- CivEngSBG6 PDFDocument98 pagesCivEngSBG6 PDFkemimeNo ratings yet

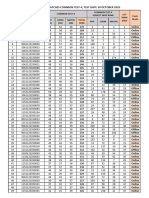

- Result Cty325 Batches Common Test-4 Test Date 30 October 2023Document14 pagesResult Cty325 Batches Common Test-4 Test Date 30 October 2023Ranveer KumarNo ratings yet

- Enterprise LMS With Adobe Captivate PrimeDocument616 pagesEnterprise LMS With Adobe Captivate Primepaulorogeriovicente_No ratings yet

- This Study Resource Was: Historical Foundation of Special Education in The PhilippinesDocument6 pagesThis Study Resource Was: Historical Foundation of Special Education in The Philippinesshara santosNo ratings yet

- Visualization Aids (Video) in Teaching and Learning Process To Overcome Under Achiever StudentsDocument22 pagesVisualization Aids (Video) in Teaching and Learning Process To Overcome Under Achiever StudentsElmifirdaus EliasNo ratings yet

- Goals and ObjectivesDocument7 pagesGoals and ObjectivesJohn WebbNo ratings yet

- B. Research Chapter 1Document26 pagesB. Research Chapter 1dominicNo ratings yet

- Gaps Model of Service QualityDocument43 pagesGaps Model of Service QualitySahil GuptaNo ratings yet

- GTS-Skill Development & PlacementDocument1 pageGTS-Skill Development & PlacementGuhanTex MktgNo ratings yet

- Detailed Lesson Plan On Inequalities in A TriangleDocument4 pagesDetailed Lesson Plan On Inequalities in A TriangleJonbert AndamNo ratings yet

- Measurement of IntelligenceDocument56 pagesMeasurement of IntelligenceEsther Faith MontillaNo ratings yet

- Data Mining Lesson Plan-Revised SyllabusDocument4 pagesData Mining Lesson Plan-Revised Syllabusrahulrnair4u_5534754No ratings yet

- Iitb Ar 2020 - 21 - 0Document152 pagesIitb Ar 2020 - 21 - 0Prakash BadalNo ratings yet

- Sociology (Lib420) Topic 1Document48 pagesSociology (Lib420) Topic 1Fahmi Ab RahmanNo ratings yet

- 23-204 Acc PGDocument3 pages23-204 Acc PGanjanamanohar94No ratings yet

- Teacher Talk - 1st Reading SummaryDocument1 pageTeacher Talk - 1st Reading SummaryLaura EnevNo ratings yet

- Cop 2021 2022-EnglishDocument8 pagesCop 2021 2022-Englishsaman jayanthaNo ratings yet

- Planificare Clasa A II-ADocument13 pagesPlanificare Clasa A II-Acristinastroe81No ratings yet