Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Political Law Review Case 23-29

Uploaded by

Jem MadridOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Political Law Review Case 23-29

Uploaded by

Jem MadridCopyright:

Available Formats

23. PHILIPPINE CONSTITUTION ASSOCIATION vs. HON.

SALVADOR ENRIQUEZ

G.R. No. 113105 August 19, 1994

FACTS: House Bill No. 10900, the GAB of 1994, was passed and approved by both houses of Congress.

As passed, it imposed conditions and limitations on certain items of appropriations in the proposed budget

previously submitted by the President. It also authorized members of Congress to propose and identify

projects in the pork barrels allotted to them and to realign their respective operating budgets. Pursuant

to the procedure on the passage and enactment of bills as prescribed by the Constitution, Congress

presented the said bill to the President for consideration and approval. President signed the bill into law,

and declared the same to have become RA NO. 7663 GAA of 1994. President delivered his Presidential

Veto Message, specifying the provisions of the bill he vetoed and on which he imposed certain

conditions, as follows: 1. Provision on Debt Ceiling, on the ground that this debt reduction scheme

cannot be validly done through the 1994 GAA; 2. Special provisions which authorize the use of income

and the creation, operation and maintenance of revolving funds in the appropriation for State Universities

and Colleges (SUCs); 3. Provision on 70% (administrative)/30% (contract) ratio for road maintenance; 4.

Special provision on the purchase by the AFP of medicines in compliance with the Generics Drugs Law

(R.A. No. 6675); 5. The President vetoed the underlined proviso in the appropriation for the

modernization of the AFP of the Special Provision No. 2 on the Use of Fund, which requires the prior

approval of the Congress for the release of the corresponding modernization funds; 6. Provision

authorizing Chief of Staff to use savings in the AFP to augment pension and gratuity funds; 7. Conditions

on the appropriation for the Supreme Court, Ombudsman, COA, and CHR, the Congress.

ISSUES:

1. WON the conditions imposed by the President in the items of the GAA of 1994 are constitutional

2. WON the veto of the special provision in the appropriation for debt service and the automatic

appropriation of funds therefore is constitutional.

HELD:

Veto of the Provisions

The veto power, while exercisable by the President, is actually a part of the legislative process. There is,

therefore, sound basis to indulge in the presumption of validity of a veto. The burden shifts on those

questioning the validity thereof to show that its use is a violation of the Constitution. The vetoed

provision on the debt servicing is clearly an attempt to repeal Section 31 of P.D. No. 1177 (Foreign

Borrowing Act) and E.O. No. 292, and to reverse the debt payment policy. As held by the court in

Gonzales, the repeal of these laws should be done in a separate law, not in the appropriations law.

In the veto of the provision relating to SUCs, there was no undue discrimination when the President

vetoed said special provisions while allowing similar provisions in other government agencies. If some

government agencies were allowed to use their income and maintain a revolving fund for that purpose, it

is because these agencies have been enjoying such privilege before by virtue of the special laws

authorizing such practices as exceptions to the one-fund policy. The veto of the second paragraph of

Special Provision No. 2 of the item for the DPWH is unconstitutional. The Special Provision in question

is not an inappropriate provision which can be the subject of a veto. It is not alien to the appropriation for

road maintenance, and on the other hand, it specifies how the said item shall be expended 70% by

administrative and 30% by contract.

Special Provision in the Appropriation for Debt Service

The appropriation law is not the proper vehicle for such purpose. Such intention must be embodied and

manifested in another law considering that it abrades the powers of the Commander-in-Chief and there

are existing laws on the creation of the CAFGUs to be amended. On the conditions imposed by the

President on certain provisions relating to appropriations to the Supreme Court, constitutional

commissions, the NHA and the DPWH, there is less basis to complain when the President said that the

expenditures shall be subject to guidelines he will issue. Until the guidelines are issued, it cannot be

determined whether they are proper or inappropriate. Under the Faithful Execution Clause, the President

has the power to take necessary and proper steps to carry into execution the law. These steps are the

ones to be embodied in the guidelines.

24 GRECO ANTONIOUS BEDA B. BELGICA vs. HONORABLE EXECUTIVE

SECRETARY PAQUITO N. OCHOA

G.R. No. 2085666 November 19, 2013

FACTS: Petitioners filed the present petitions for certiorari and prohibition in their capacity as taxpayers

and Filipino citizens, challenging the constitutionality of the PDAF provisions in the 2013 GAA and

certain provisions in Presidential Decree Nos. 910 and 1869. "Pork Barrel" has been typically associated

with lump-sum, discretionary funds of Members of Congress, the present cases and the recent

controversies on the matter has expanded to include certain funds of the President such as the Malampaya

Funds and the Presidential Social Fund. Malampaya Funds was created as a special fund PD 910, issued

by then President Marcos. Marcos recognized the need to set up a special fund to help intensify,

strengthen, and consolidate government efforts relating to the exploration, exploitation, and development

of indigenous energy resources vital to economic growth. Presidential Social Fund was created under PD

1869, or the Charter of the PAGCOR. PD 1869 was similarly issued by Marcos. As it stands, the

Presidential Social Fund has been described as a special funding facility managed and administered by the

Presidential Management Staff through which the President provides direct assistance to priority

programs and projects not funded under the regular budget. It is sourced from the share of the government

in the aggregate gross earnings of PAGCOR.

Petitioners filed for seeking that the "Pork Barrel System" be declared unconstitutional and the

Executives lump-sum, discretionary funds, such as the Malampaya Funds and the Presidential Social

Fund, be declared unconstitutional and null and void for being acts constituting grave abuse of discretion.

Office of the Solicitor General (OSG) filed a Consolidated Comment before the SC, seeking the lifting, or

in the alternative, the partial lifting with respect to educational and medical assistance purposes, of the

Courts TRO, and that the consolidated petitions be dismissed for lack of merit.

ISSUES:

1. WON the 2013 PDAF Article and all other Congressional Pork Barrel Laws similar thereto are

unconstitutional considering that they violate the principles of/constitutional provisions;

2. WON the phrases relating to the Malampaya Funds, and to finance the priority infrastructure

development projects relating to the Presidential Social Fund, are unconstitutional insofar as they

constitute undue delegations of legislative power.

HELD: The petitions are PARTLY GRANTED. In view of the constitutional violations, the Court

hereby declares as UNCONSTITUTIONAL (a)entire 2013 PDAF Article; (b) all legal provisions of past

and present Congressional Pork Barrel Laws, such as the previous PDAF and CDF Articles and the

various Congressional Insertions, which authorize/d legislators whether individually or collectively

organized into committees to intervene, assume or participate in any of the various post-enactment

stages of the budget execution, such as but not limited to the areas of project identification, modification

and revision of project identification, fund release and/or fund realignment, unrelated to the power of

congressional oversight.

Non-delegability of Legislative Powe; Checks and Balances

The Court observes that the 2013 PDAF Article, insofar as it confers post-enactment identification

authority to individual legislators, violates the principle of non-delegability since said legislators are

effectively allowed to individually exercise the power of appropriation. That the power to appropriate

must be exercised only through legislation is clear from Section 29(1), Article VI of the 1987 Constitution

which states that: No money shall be paid out of the Treasury except in pursuance of an appropriation

made by law. The power of appropriation involves (a) the setting apart by law of a certain sum from the

public revenue for (b) a specified purpose. 2013 PDAF Article authorizes individual legislators

to perform the same, undoubtedly, said legislators have been conferred the power to legislate which the

Constitution does not, however, allow. To a certain extent, the conduct of oversight would be tainted as

said legislators, who are vested with post-enactment authority, would, in effect, be checking on activities

in which they themselves participate. Clearly, allowing legislators to intervene in the various phases

of project implementation a matter before another office of government renders them susceptible to

taking undue advantage of their own office.

Malampaya Fund

While the designation of a determinate or determinable amount for a particular public purpose is

sufficient for a legal appropriation to exist, the appropriation law must contain adequate legislative

guidelines if the same law delegates rule-making authority to the Executive either for the purpose of (a)

filling up the details of the law for its enforcement, known as supplementary rule-making, or (b)

ascertaining facts to bring the law into actual operation, referred to as contingent rule-making. There are

two (2) fundamental tests to ensure that the legislative guidelines for delegated rule-making are indeed

adequate. The first test is called the completeness test. Case law states that a law is complete when it sets

forth therein the policy to be executed, carried out, or implemented by the delegate. The second test is

called the sufficient standard test. To be sufficient, the standard must specify the limits of the delegates

authority, announce the legislative policy, and identify the conditions under which it is to be

implemented. Section 8 of PD 910 constitutes an undue delegation of legislative power insofar as it does

not lay down a sufficient standard to adequately determine the limits of the Presidents authority with

respect to the purpose for which the Malampaya Funds may be used. The said phrase gives the President

wide latitude to use the Malampaya Funds for any other purpose he may direct and, in effect, allows him

to unilaterally appropriate public funds beyond the purview of the law. That the subject phrase may be

confined only to energy resource development and exploitation programs and projects of the

government under the principle of ejusdem generis, general word or phrase is to be construed to include

or be restricted to things akin to, resembling, or of the same kind or class as those specifically

mentioned. Thus, while Section 8 of PD 910 may have passed the completeness test since the policy of

energy development is early deducible from its text, the phrase and for such other purposes as may

be hereafter directed by the President under the same provision of law should nonetheless be stricken

down as unconstitutional as it lies independently unfettered by any sufficient standard of the delegating

law.

25 MARIA CAROLINA P. ARAULLO, ET AL VS. BENIGNO SIMEON AQUINO, III

G.R. No. 209287 July 1, 2014

FACTS: During the official budget deliberation of the DBCC and DBM, Rep. Neri Colmenares of Bayan Muna

Party-list inquired from the DBM Secretary, Respondent Florencio Abad about the nature of the DBM

National Budget Circular No. 541 (NBC 541). Sec. Abad informed the Appropriations Committee that

NBC541 is intended to accelerate disbursement under a then unknown DAP by withdrawing unobligated

allotments from under-spending agencies. When asked by Rep. Colmenares whether NBC 541 is

constitutional considering that it authorizes withdrawal of funds midyear and realigns it to other projects,

Sec. Abad maintained that it is only intended to be realigned for existing projects anyway. He further

stated that if the withdrawn funds will be spent on projects not contained in the General Appropriations

Act then indeed it would be unconstitutional. Estrada said that after the conviction of Corona in May

2012, those who voted to convict him were allotted an additional P50 Million, as provided in a private

and confidential letter memorandum by the then Chairman of the Senate Finance Committee. In his

speech, Estrada dubbed the additional amount as incentive for Coronas ouster. Sec. Abad issued a

statement through the DBM website explaining the purpose of the additional fund releases to senators as

mentioned in the speech of Sen. Estrada and said that the same came from the Disbursement Acceleration

Program (DAP). According to Sec. Abad these funds were not bribes, but were necessary to help

accelerate economic expansion. He funding for DAP, the respondents said came from pooled

savingsand the Unprogrammed Fund. The so-called savings, camefrom the centralization of unreleased

appropriations such as unreleased Personnel Services appropriations, unreleased appropriations of slow

moving projects and discontinued projects and the withdrawal of unobligated allotments, also for slow-

moving programs and projects, which have earlier been released to national government agencies. More

importantly, the transfer or realignment of funds did not only went border crossing, but it even included

funding for new projects. In his memorandum to the President, Sec. Abad said that the pooled savings

were also intended for new activities which have not been anticipated during the preparation of the

budget and to provide for deficiencies under the Special Purpose Funds e.g. PDAF, Calamity

Fund and Contingent Fund.

ISSUES:

1. WON the DAP, NBC No. 541, and all other executive issuances allegedly implementing the DAP

violate Sec. 25(5), Art. VI of the 1987 Constitution insofar as they treat the unreleased appropriations

and unobligated allotments withdrawn from government agencies as savings; they authorize the

disbursement of funds for projects or programs not provided in the GAAs for the Executive

Department; and they augment discretionary lump sum appropriations in the GAAs.

2. WON the DAP violates: (1) the Equal Protection Clause, (2) the system of checks and balances, and

(3) the principle of public accountability enshrined in the 1987 Constitution considering that it

authorizes the release of funds upon the request of legislators.

HELD:

DAP is unconstitutional.

No less than the Constitution mandates that public funds will not be paid out of the national treasury

exception through an appropriation law enacted by Congress. Congress alone can authorize the

expenditure of public funds through its power to appropriate. The power to appropriate carries with it the

power to specify not just the amount that may be spent but also the purpose for which it may be spent.

Tantamount to appropriating public funds, the NBC 541 authorizes the funding priority programs and

projects not considered in the 2012. While being peddled as a stimulus package, the DAP is actually an

appropriation law which seeks to set aside public funds for public use. Sec. 24 Art. VI of the 1987

Constitution requires that all appropriation bills shall originate exclusively in the HR. The DAP, not being

initiated by the HR, is unconstitutional. Moreover, no appropriation law was enacted stating the amount

that may be spent for DAP, as well as the purpose for which the DAP may be spent. No appropriation law

was enacted by Congress creating DAP. The cited provisions by Respondents do not amount to an

appropriation law, but merely a futile and belated attempt to justify an illegal appropriation and

disbursement of public funds and usurpation of the legislatives power to appropriate public funds. NBC

541 is an appropriation of public funds by the Executive, which did not originate in the HR as mandated

by Sec. 24, Art. VI of the 1987 Constitution which provides: All appropriation, revenue or tariff bills,

bills authorizing the increase of the public debt, bills of local application, and private bills shall originate

exclusively in the House of Representatives, but the Senate may propose or concur with amendments.

The rule on the use and transfer of funds is clear as it is meticulously laid down in Art. VI, Section 25 (5)

of our Constitution: No law shall be passed authorizing any transfer of appropriations; however, the

President, the President of the Senate, the Speaker of the House of Representatives, the Chief Justice of

the Supreme Court, and the heads of the Constitutional Commissions may, by law, be authorized to

augment any item in the general appropriations law for their respective offices from savings in other items

of their respective appropriations.Section 25 (5) Article VI of the 1987 Constitution prohibits transfer of

appropriations. This simply means that once Congress passes the General Appropriation Act (GAA) or

any appropriation law, with or without any veto from the President, the same remains unalterable and

must be executed to the letter. The appropriations law becomes the law of the land, a product of the

collective effort of the representatives of the people and the different government agencies. Those who

have participated in the yearly budget process would knowhow arduous, detailed, and lengthy such a

process is, with government agencies listing all their spending in the previous year and coming up with

new projects needing funding; preparing for the justifications for each and every line item budget in case

Congress would ask for the wisdom of such an expenditure; as well as preparing for both parochial and

national concerns that may be raised by Congress during the budget deliberation/interpellation which may

or may not be related to the agencies budget but has an effect on its overall performance as an agency.

Congress has to contend with poring over at least 5 budget books -the National Expenditure Program,

Budget of Expenditure and Sources of Financing, Staffing Summary and Details of the Budget 1and 2

and studying the spending history/backgrounds and budget requests of each and every agency; reviewing

the agencys previous claims and promises; and most importantly, the impact of the agencies past budget

and current proposal to a particular lawmakers district or constituency. This being the case, the resulting

appropriations law is not a simple feat that should easily be trifled with. Not even Congress who passed it

can alter the same, without under going the same tedious process of enacting or amending a law. Such

is the wisdom of our Constitution. As a limited grant nevertheless, the Constitution allows the President,

President of the Senate, Speaker of the House, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, and the heads of

Constitutional Commissions, to transfer of appropriations ONLY in specific circumstances: (1) if there is

a law; (2) if there are savings; and (3) only to augment any item in the general appropriations law for their

respective offices. The creation and implementation of the DAP and the NBC 541 violate the above-

stated provision.

26 STANDARD CHARTERED BANK (Philippine Branch) vs. SENATE COMMITTEE

ON BANKS

G.R. No. 167173 December 27, 2007

FACTS: Petition for Prohibition (With Prayer for Issuance of TRO and/or Injunction) filed by

petitioners. SCB is a bank instituted in England. Petitioners are Executive officers of said bank.

Respondent is one of the permanent committees of the Senate. Petition seeks the issuance of a TRO to

enjoin respondent from (1) proceeding with its inquiry pursuant to Philippine Senate (P.S.) Resolution

No. 166; (2) compelling petitioners who are officers of SCB-Philippines to attend and testify before any

further hearing to be conducted by respondent; and (3) enforcing any hold-departure order (HDO) and/or

putting the petitioners on the Watch List. It also prays that judgment be rendered (1) annulling the

subpoenae ad testificandum and duces tecum issued to petitioners, and (2) prohibiting the respondent

from compelling petitioners to appear and testify in the inquiry being conducted pursuant to P.S.

Resolution No. 166. Senator Juan Ponce Enrile, delivered a privilege speech entitled Arrogance of

Wealth before the Senate based on a letter from Atty. Mark R. Bocobo denouncing SCB-Philippines for

selling unregistered foreign securities in violation of the Securities Regulation Code (R.A. No. 8799) and

urging the Senate to immediately conduct an inquiry, in aid of legislation, to prevent the occurrence of a

similar fraudulent activity in the future. Prior to the privilege speech, Senator Enrile had introduced P.S.

Resolution No. 166, DIRECTING THE COMMITTEE ON BANKS, FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS AND

CURRENCIES, TO CONDUCT AN INQUIRY, IN AID OF LEGISLATION, INTO THE ILLEGAL SALE

OF UNREGISTERED AND HIGH-RISK SECURITIES BY STANDARD CHARTERED BANK, WHICH

RESULTED IN BILLIONS OF PESOS OF LOSSES TO THE INVESTING PUBLIC. Acting on the

referral, Senator Edgardo J. Angara, set the initial hearing to investigate, in aid of legislation, the subject

matter of the speech and resolution filed by Senator Enrile. Respondent invited petitioners to attend the

hearing, requesting them to submit their written position paper. Senator Enrile inquired who among those

invited as resource persons were present and who were absent. Senator Enrile moved that subpoena be

issued to those who did not attend the hearing and that the Senate request the DOJ, through the Bureau of

Immigration, to issue an HDO against them and/or include them in the Bureaus Watch List. Senator

Juan Flavier seconded the motion and the motion was approved. Respondent then proceeded with the

investigation proper. Towards the end of the hearing, petitioners, through counsel, made an Opening

Statement that brought to the attention of respondent the lack of proper authorization from affected clients

for the bank to make disclosures of their accounts and the lack of copies of the accusing documents

mentioned in Senator Enrile's privilege speech, and reiterated that there were pending court cases

regarding the alleged sale in the Philippines by SCB-Philippines of unregistered foreign securities.

ISSUE: WON SCB-Philippines illegally sold unregistered foreign securities is already preempted by the

courts that took cognizance of the foregoing cases, the respondent, by this investigation, would encroach

upon the judicial powers vested solely in these courts.

HELD: Contention is UNTENABLE. P.S. Resolution No. 166 is explicit on the subject and nature of the

inquiry to be conducted by the Committee, as found in the last three Whereas clauses thereof. The

unmistakable objective of the investigation exposes the error in petitioners allegation that the inquiry, as

initiated in a privilege speech by the very same Senator Enrile, was simply to denounce the illegal

practice committed by a foreign bank in selling unregistered foreign securities x x x. This fallacy is

made more glaring when we consider that, at the conclusion of his privilege speech, Senator Enrile urged

the Senate to immediately conduct an inquiry, in aid of legislation, so as to prevent the occurrence

of a similar fraudulent activity in the future. In Arnault vs. Nazareno, the power of inquiry with

process to enforce it is an essential and appropriate auxiliary to the legislative function. A legislative

body cannot legislate wisely or effectively in the absence of information respecting the conditions which

the legislation is intended to affect or change; and where the legislative body does not itself possess the

requisite information which is not infrequently true recourse must be had to others who possess it.

The exercise by Congress or by any of its committees of the power to punish contempt is based on the

principle of self-preservation. As the branch of the government vested with the legislative power,

independently of the judicial branch, it can assert its authority and punish contumacious acts against it.

Such power is sui generis, as it attaches not to the discharge of legislative functions per se, but to the

sovereign character of the legislature as one of the three independent and coordinate branches of

government. In this case, petitioners imputation that the investigation was in aid of collection is a

direct challenge against the authority of the Senate Committee, as it ascribes ill motive to the latter. In

this light, we find the contempt citation against the petitioners reasonable and justified.

27 ROMULO L. NERI vs. SENATE COMMITTEE ON ACCOUNTABILITY OF

PUBLIC OFFICERS AND INVESTIGATIONS, et al.

G.R. No. 180643 March 25, 2008

FACTS: Petitioner appeared before respondent Committees and testified on matters concerning the

National Broadband Project, a project awarded by the DOTC to Zhong Xing Telecommunications

Equipment (ZTE). Petitioner disclosed that COMELEC Chairman Benjamin Abalos offered him P200

Million in exchange for his approval of the NBN Project. He further narrated that he informed President

Arroyo of the bribery attempt and that she instructed him not to accept the bribe. However, when probed

further on President Arroyo and petitioners discussions relating to the NBN Project, petitioner refused to

answer, invoking executive privilege. To be specific, petitioner refused to answer questions on: (a)

whether or not President Arroyo followed up the NBN Project, (b) whether or not she directed him to

prioritize it, and (c) whether or not she directed him to approve it. Committees persisted in knowing

petitioners answers to these 3 questions by requiring him to appear and testify once more. Executive

Secretary Eduardo R. Ermita wrote to respondent Committees and requested them to dispense with

petitioners testimony on the ground of executive privilege. The senate thereafter issued a show cause

order, unsatisfied with the reply, therefore, issued an Order citing Neri in contempt and ordering his arrest

and detention at the Office of the Senate Sergeant-at-Arms until such time that he would appear and give

his testimony. Petition for certiorari and Supplemental Petition for Certiorari (with Urgent Application for

TRO/Preliminary Injunction) granted by the SC court.

ISSUES:

(1) WON there is a recognized presumptive presidential communications privilege in our legal system;

(2) WON there is factual or legal basis to hold that the communications elicited by the three (3) questions

are covered by executive privilege;

(3) WON Committees committed grave abuse of discretion in issuing the contempt order.

HELD:

There Is a Recognized Presumptive Presidential Communications Privilege

Committees argue as if this were the first time the presumption in favor of the presidential

communications privilege is mentioned and adopted in our legal system. That is far from the truth. The

Court articulated in cases that, the right to information does not extend to matters recognized as

privileged information under the separation of powers, by which the Court meant Presidential

conversations, correspondences, and discussions in closed-door Cabinet meetings. In this case, it was the

President herself, through Executive Secretary Ermita, who invoked executive privilege on a specific

matter involving an executive agreement between the Philippines and China, which was the subject of the

three (3) questions propounded to petitioner Neri in the course of the Senate Committees investigation. A

President and those who assist him must be free to explore alternatives in the process of shaping policies

and making decisions and to do so in a way many would be unwilling to express except privately. These

are the considerations justifying a presumptive privilege for Presidential communications. The privilege is

fundamental to the operation of government and inextricably rooted in the separation of powers under the

Constitution.

There Are Factual and Legal Bases to Hold that the Communications Elicited by the Three (3)

Questions Are Covered by Executive Privilege

A. The power to enter into an executive agreement is a quintessential and non-delegable presidential

power. Committees contend that the power to secure a foreign loan does not relate to a quintessential

and non-delegable presidential power, because the Constitution does not vest it in the President alone,

but also in the Monetary Board which is required to give its prior concurrence and to report to Congress.

This argument is unpersuasive. The fact that a power is subject to the concurrence of another entity does

not make such power less executive. The power to enter into an executive agreement is in essence an

executive power. This authority of the President to enter into executive agreements without the

concurrence of the Legislature has traditionally been recognized in Philippine jurisprudence. Now, the

fact that the President has to secure the prior concurrence of the Monetary Board, which shall submit to

Congress a complete report of its decision before contracting or guaranteeing foreign loans, does not

diminish the executive nature of the power. In the same way that certain legislative acts require action

from the President for their validity does not render such acts less legislative in nature.

B. The doctrine of operational proximity was laid down precisely to limit the scope of the presidential

communications privilege but, in any case, it is not conclusive. Committees also seek reconsideration of

the application of the doctrine of operational proximity for the reason that it maybe misconstrued to

expand the scope of the presidential communications privilege to communications between those who are

operationally proximate to the President but who may have no direct communications with her. It

must be stressed that the doctrine of operational proximity was laid down precisely to limit the scope of

the presidential communications privilege. In the case at bar, the danger of expanding the privilege to a

large swath of the executive branch is absent because the official involved here is a member of the

Cabinet, thus, properly within the term advisor of the President; in fact, her alter ego and a member of

her official family.

C. The Presidents claim of executive privilege is not merely based on a generalized interest; and in

balancing respondent Committees and the Presidents clashing interests, the Court did not disregard the

1987 Constitutional provisions on government transparency, accountability and disclosure of information.

The nature of diplomacy requires centralization of authority and expedition of decision which are inherent

in executive action. Another essential characteristic of diplomacy is its confidential nature. With respect

to respondent Committees invocation of constitutional prescriptions regarding the right of the people to

information and public accountability and transparency, the Court finds nothing in these arguments to

support respondent Committees case. There is no debate as to the importance of the constitutional right

of the people to information and the constitutional policies on public accountability and transparency.

These are the twin postulates vital to the effective functioning of a democratic government. In the case at

bar, this Court, in upholding executive privilege with respect to three (3) specific questions, did not in any

way curb the publics right to information or diminish the importance of public accountability and

transparency.

Committees Committed Grave Abuse of Discretion in I ssuing the Contempt Order

Respondent Committees contend that their Rules of Procedure Governing Inquiries in Aid of Legislation

(the Rules) are beyond the reach of this Court. While it is true that this Court must refrain from

reviewing the internal processes of Congress, as a co-equal branch of government, however, when a

constitutional requirement exists, the Court has the duty to look into Congress compliance therewith. We

cannot turn a blind eye to possible violations of the Constitution simply out of courtesy. Section 21,

Article VI of the Constitution states that: The Senate or the House of Representatives or any of its

respective committees may conduct inquiries in aid of legislation in accordance with its duly published

rules of procedure. The rights of person appearing in or affected by such inquiries shall be respected.

28 VIRGILIO O. GARCILLANO vs. THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES

COMMITTEES ON PUBLIC INFORMATION, et al

G.R. No. 170338 December 23, 2008

FACTS: Tapes ostensibly containing a wiretapped conversation purportedly between the President of the

Philippines and a high-ranking official of the COMELEC surfaced. The tapes, notoriously referred to as

the "Hello Garci" tapes, allegedly contained the Presidents instructions to COMELEC Commissioner

Virgilio Garcillano to manipulate in her favor results of the 2004 presidential elections. These recordings

were to become the subject of heated legislative hearings conducted separately by committees of both

Houses of Congress. In one of the Senates plenary session, a lengthy debate ensued when Senator

Richard Gordon aired his concern on the possible transgression of Republic Act (R.A.) No. 4200 if the

body were to conduct a legislative inquiry on the matter. Senator Miriam Defensor-Santiago delivered a

privilege speech, articulating her considered view that the Constitution absolutely bans the use,

possession, replay or communication of the contents of the "Hello Garci" tapes. However, she

recommended a legislative investigation into the role of the Intelligence Service of the AFP (ISAFP), the

Philippine National Police or other government entities in the alleged illegal wiretapping of public

officials. Petitioners Santiago Ranada and Oswaldo Agcaoili, retired justices of CA, filed before this

Court a Petition for Prohibition with Prayer for the Issuance of a TRO and/or Writ of Preliminary

Injunction, seeking to bar the Senate from conducting its scheduled legislative inquiry. They argued in the

main that the intended legislative inquiry violates R.A. No. 4200 and Section 3, Article III of the

Constitution.

ISSUE: WON the publication of the Rules of Procedure in the website of the Senate, or in pamphlet form

available at the Senate, is sufficient compliance of the publication requirement prior to the effectivity of

laws and other issuances.

HELD: SC dismissed the petition in G.R. No. 170338 but granted the petition in G.R. No. 179275. A writ

of prohibition was issued enjoining the Senate of the Republic of the Philippines and/or any of its

committees from conducting any inquiry in aid of legislation centered on the "Hello Garci" tapes. The

Court held that the Senate cannot be allowed to continue with the conduct of the questioned legislative

inquiry without duly published rules of procedure, in clear derogation of the constitutional requirement.

Section 21, Article VI of the 1987 Constitution explicitly provides that "[t]he Senate or the House of

Representatives, or any of its respective committees may conduct inquiries in aid of legislation in

accordance with its duly published rules of procedure."

The phrase "duly published rules of procedure" requires the Senate of every Congress to publish its rules

of procedure governing inquiries in aid of legislation because every Senate is distinct from the one before

it or after it. Respondents justify their non-observance of the constitutionally mandated publication by

arguing that the rules have never been amended since 1995 and, despite that, they are published in booklet

form available to anyone for free, and accessible to the public at the Senates internet web page. The

Court did not agree. The absence of any amendment to the rules cannot justify the Senates defiance of

the clear and unambiguous language of Section 21, Article VI of the Constitution. Senate Committees,

therefore, could not, in violation of the Constitution, use its unpublished rules in the legislative inquiry

subject of these consolidated cases. The conduct of inquiries in aid of legislation by the Senate has to be

deferred until it shall have caused the publication of the rules, because it can do so only "in accordance

with its duly published rules of procedure."

29 SENATE OF THE PHILIPPINES vs. EDUARDO R. ERMITA

G.R. No. 169777 April 20, 2006

FACTS: In 2005, scandals involving anomalous transactions surfaced, this prompted the Senate to

conduct a public hearing to investigate the said anomalies particularly the alleged overpricing in the NRP.

The investigating Senate committee issued invitations to certain department heads and military officials to

speak before the committee as resource persons. Ermita submitted that he and some of the department

heads cannot attend the said hearing due to pressing matters that need immediate attention. AFP Chief of

Staff Senga likewise sent a similar letter. Drilon, the senate president, excepted the said requests for they

were sent belatedly and arrangements were already made and scheduled. GMA issued EO 464 which took

effect immediately. EO 464 basically prohibited Department heads, Senior officials of executive

departments who in the judgment of the department heads are covered by the executive privilege;

Generals and flag officers of the AFP and such other officers who in the judgment of the Chief of Staff

are covered by the executive privilege; PNP officers with rank of chief superintendent or higher and such

other officers who in the judgment of the Chief of the PNP are covered by the executive privilege; Senior

national security officials who in the judgment of the National Security Adviser are covered by the

executive privilege; and Such other officers as may be determined by the President, from appearing in

such hearings conducted by Congress without first securing the presidents approval.

The department heads and the military officers who were invited by the Senate committee then invoked

EO 464 to except themselves. Despite EO 464, the scheduled hearing proceeded with only 2 military

personnel attending. For defying President Arroyos order barring military personnel from testifying

before legislative inquiries without her approval, Brig. Gen. Gudani and Col. Balutan were relieved from

their military posts and were made to face court martial proceedings. EO 464s constitutionality was

assailed for it is alleged that it infringes on the rights and duties of Congress to conduct investigation in

aid of legislation and conduct oversight functions in the implementation of laws.

ISSUE: WON EO 464 is constitutional.

HELD: SC ruled that EO 464 is constitutional in part. To determine the validity of the provisions of EO

464, the SC sought to distinguish Section 21 from Section 22 of Art 6 of the 1987 Constitution. The

Congress power of inquiry is expressly recognized in Section 21 of Article VI of the Constitution.

Although there is no provision in the Constitution expressly investing either House of Congress with

power to make investigations and exact testimony to the end that it may exercise its legislative functions

advisedly and effectively, such power is so far incidental to the legislative function as to be implied. The

power of inquiry with process to enforce it is an essential and appropriate auxiliary to the legislative

function. A legislative body cannot legislate wisely or effectively in the absence of information

respecting the conditions which the legislation is intended to affect or change; and where the legislative

body does not itself possess the requisite information which is not infrequently true recourse must be

had to others who do possess it. Section 22 provides for the Question Hour. The Question Hour is closely

related with the legislative power, and it is precisely as a complement to or a supplement of the

Legislative Inquiry. Section 22 refers only to Question Hour, whereas, Section 21 would refer

specifically to inquiries in aid of legislation, under which anybody for that matter, may be summoned and

if he refuses, he can be held in contempt of the House. Ultimately, the power of Congress to compel the

appearance of executive officials under Section 21 and the lack of it under Section 22 find their basis in

the principle of separation of powers.

While the executive branch is a co-equal branch of the legislature, it cannot frustrate the power of

Congress to legislate by refusing to comply with its demands for information. When Congress exercises

its power of inquiry, the only way for department heads to exempt themselves therefrom is by a valid

claim of privilege. They are not exempt by the mere fact that they are department heads. Only one

executive official may be exempted from this power the President on whom executive power is vested,

hence, beyond the reach of Congress except through the power of impeachment. It is based on her being

the highest official of the executive branch, and the due respect accorded to a co-equal branch of

government which is sanctioned by a long-standing custom. The requirement then to secure presidential

consent under Section 1, limited as it is only to appearances in the question hour, is valid on its face. For

under Section 22, Article VI of the Constitution, the appearance of department heads in the question hour

is discretionary on their part. Section 1 cannot, however, be applied to appearances of department heads

in inquiries in aid of legislation. Congress is not bound in such instances to respect the refusal of the

department head to appear in such inquiry, unless a valid claim of privilege is subsequently made, either

by the President herself or by the Executive Secretary. In such instances, Section 22, in keeping with the

separation of powers, states that Congress may only request their appearance. Nonetheless, when the

inquiry in which Congress requires their appearance is in aid of legislation under Section 21, the

appearance is mandatory.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Agoda, Look AlikeDocument1 pageAgoda, Look AlikeJem MadridNo ratings yet

- REM1Document48 pagesREM1Jem MadridNo ratings yet

- Civil Law-For WritingDocument4 pagesCivil Law-For WritingJem MadridNo ratings yet

- This Case Is A Constitutional/political Case As This Case Talks About CitizenshipDocument4 pagesThis Case Is A Constitutional/political Case As This Case Talks About CitizenshipJem MadridNo ratings yet

- Oath of OfficeDocument1 pageOath of OfficeJem MadridNo ratings yet

- PROFDocument12 pagesPROFJem MadridNo ratings yet

- My Digest Poli ReviewDocument32 pagesMy Digest Poli ReviewJem MadridNo ratings yet

- Dead As DiscoDocument1 pageDead As DiscoJem MadridNo ratings yet

- Political Law Review Case 23-29Document2 pagesPolitical Law Review Case 23-29Jem MadridNo ratings yet

- Criminal Law Review Case DigestDocument1 pageCriminal Law Review Case DigestJem MadridNo ratings yet

- Legal EthicsDocument15 pagesLegal EthicsJem MadridNo ratings yet

- Favor LetterDocument2 pagesFavor LetterJem MadridNo ratings yet

- GG and DevelopmentDocument13 pagesGG and DevelopmentJem MadridNo ratings yet

- Digest Political LawDocument12 pagesDigest Political LawJem MadridNo ratings yet

- Dead As DiscoDocument1 pageDead As DiscoJem MadridNo ratings yet

- Oath of OfficeDocument1 pageOath of OfficeJem MadridNo ratings yet

- Digest Political LawDocument12 pagesDigest Political LawJem MadridNo ratings yet

- NicaDocument15 pagesNicaJem MadridNo ratings yet

- Philippine Development PlanDocument5 pagesPhilippine Development PlanJem MadridNo ratings yet

- PROFDocument12 pagesPROFJem MadridNo ratings yet

- Notice of DishonorDocument1 pageNotice of DishonorJem Madrid100% (1)

- Letter From CA MidasDocument1 pageLetter From CA MidasJem MadridNo ratings yet

- SosDocument9 pagesSosJem MadridNo ratings yet

- New Cases 002Document106 pagesNew Cases 002Jem MadridNo ratings yet

- A C B O 2007 Legal Ethics: Summer ReviewerDocument27 pagesA C B O 2007 Legal Ethics: Summer ReviewerMiGay Tan-Pelaez97% (32)

- Rule 133Document9 pagesRule 133Jem MadridNo ratings yet

- How To Prepare For The Bar ExamDocument3 pagesHow To Prepare For The Bar ExamJhoey BuenoNo ratings yet

- Testimonial of Good Moral CharacterDocument1 pageTestimonial of Good Moral CharacterZendy PastoralNo ratings yet

- PhilosophyDocument10 pagesPhilosophyJem MadridNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Crimea's Self-Determination in The Light of Contemporary International LawDocument18 pagesCrimea's Self-Determination in The Light of Contemporary International LawCates TorresNo ratings yet

- Cestui Que Vie Act 1666Document2 pagesCestui Que Vie Act 1666cregzlistcruzr67% (3)

- United Kingdom EssayDocument4 pagesUnited Kingdom Essayafabfzoqr100% (2)

- Unit 1Document7 pagesUnit 1jyothi g sNo ratings yet

- Statutory Construction FinalsDocument22 pagesStatutory Construction FinalsRussell Marquez ManglicmotNo ratings yet

- Legal System NotesDocument124 pagesLegal System NotesGEOFFREY KAMBUNI100% (1)

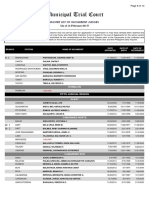

- Municipal Trial Court: Master List of Incumbent JudgesDocument1 pageMunicipal Trial Court: Master List of Incumbent JudgesStrawberryNo ratings yet

- Caudal vs. Court of AppealsDocument2 pagesCaudal vs. Court of AppealsLaw2019upto20240% (1)

- Structure of The Birth Certificate PDFDocument6 pagesStructure of The Birth Certificate PDFEugene S. Globe III100% (1)

- PSBA V Noriel - NarvacanDocument2 pagesPSBA V Noriel - NarvacanMarc VirtucioNo ratings yet

- The 1973 Constitution of Pakistan Was Adopted On April 12Document11 pagesThe 1973 Constitution of Pakistan Was Adopted On April 12Sheraz AliNo ratings yet

- Garcia Vs Drilon - DigestDocument6 pagesGarcia Vs Drilon - DigestJoanna E100% (1)

- VALMONTE and DE VILLADocument3 pagesVALMONTE and DE VILLASu Kings AbetoNo ratings yet

- Consti2 PolicepowerDocument132 pagesConsti2 PolicepowerlitoingatanNo ratings yet

- Mercado Vs Board of Election SupervisorsDocument2 pagesMercado Vs Board of Election Supervisorsajyu100% (1)

- Keith Fulton & Sons, Inc. v. New England Teamsters and Trucking Industry Pension Fund, Inc., 762 F.2d 1137, 1st Cir. (1985)Document21 pagesKeith Fulton & Sons, Inc. v. New England Teamsters and Trucking Industry Pension Fund, Inc., 762 F.2d 1137, 1st Cir. (1985)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- C M S O S D F J P S O F R 26 C: Case 4:14-cv-00622-ODS Document 24 Filed 09/09/14 Page 1 of 3Document3 pagesC M S O S D F J P S O F R 26 C: Case 4:14-cv-00622-ODS Document 24 Filed 09/09/14 Page 1 of 3Equality Case FilesNo ratings yet

- Bunag V Court of Appeals - GR No. 101749Document1 pageBunag V Court of Appeals - GR No. 101749moeen basayNo ratings yet

- Rebecca Fullido Vs Gino Grilli - GR No. 215014 - February 29, 2016Document8 pagesRebecca Fullido Vs Gino Grilli - GR No. 215014 - February 29, 2016BerniceAnneAseñas-ElmacoNo ratings yet

- Republic vs. Pilipinas ShellDocument3 pagesRepublic vs. Pilipinas ShellJu LanNo ratings yet

- Conflict of Laws ReviewerDocument14 pagesConflict of Laws ReviewerMark Lojero100% (1)

- Resolution Approving The Barangay Devolution Transition PlanDocument2 pagesResolution Approving The Barangay Devolution Transition PlanVirgo Cayaba88% (25)

- State V HolmDocument3 pagesState V HolmSheyNo ratings yet

- Moldex Realty V HlurbDocument3 pagesMoldex Realty V Hlurbtrish bernardoNo ratings yet

- National Service Training Program1: Ms - Viray (Module 3 - IT1&HRS1)Document3 pagesNational Service Training Program1: Ms - Viray (Module 3 - IT1&HRS1)Guki SuzukiNo ratings yet

- Hollis v. United States of America (INMATE 1) - Document No. 3Document2 pagesHollis v. United States of America (INMATE 1) - Document No. 3Justia.comNo ratings yet

- USMAF Cont BylawDocument25 pagesUSMAF Cont BylawartiemaskNo ratings yet

- MerdekaDocument1 pageMerdekaFaizul HishamNo ratings yet

- Jurisprudence IIDocument25 pagesJurisprudence IILemmebeyo Hero100% (1)

- Seminar Course ReportDocument88 pagesSeminar Course ReportSagar YadavNo ratings yet