Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Lexical Semantics: Encyclopedia of Cognitive Science-Author Stylesheet

Lexical Semantics: Encyclopedia of Cognitive Science-Author Stylesheet

Uploaded by

Nordiana SalimOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Lexical Semantics: Encyclopedia of Cognitive Science-Author Stylesheet

Lexical Semantics: Encyclopedia of Cognitive Science-Author Stylesheet

Uploaded by

Nordiana SalimCopyright:

Available Formats

Encyclopedia of Cognitive ScienceAuthor Stylesheet

ECS 235

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF COGNITIVE SCIENCE

2000

Macmillan Reference Ltd

Lexical Semantics

Semantics#linking#thematic roles#argument structure#concepts

Barker, Chris

Chris Barker

University of California, San Diego USA

Word meaning mediates

between conceptualization

and language: simply put,

words name concepts.

Studying which concepts

can have names---and how

the fine-grained structure

of those concepts interacts

with the linguistic

structures that contain

them---reveals something

important about the

nature of language and

cognition.

What can words mean?

To a first approximation, lexemes are words, so lexical semantics is the study of word

meaning. The main reason why word-level semantics is especially interesting from a

cognitive point of view is that words are names for individual concepts. Thus lexical

semantics is the study of those concepts that have names. The question What can

words mean?, then, amounts to the question What concepts can have names?

There are many more or less familiar concepts that can be expressed by language but

for which there is no corresponding word. There is no single word in English that

specifically names the smell of a peach, or the region of soft skin on the underside of

the forearm, though presumably there could be. Furthermore, it is common for one

language to choose to lexicalize a slightly different set of concepts than another.

American speakers do not have a noun that is exactly equivalent to the British toff

`conceited person', nor does every language have a verb equivalent to the American

bean `to hit on the head with a baseball'.

Copyright Macmillan Reference Ltd

23 May, 2001

Page 1

Encyclopedia of Cognitive ScienceAuthor Stylesheet

The situation is quite different for other concepts, however. To adapt a famous

example from philosophy, there is no word in any language that refers specifically to

objects that were green before January 1, 2000 but blue afterwards. Of course, we can

artificially agree to assign this concept to a made-up word; in fact, let's call it grue

[xref: Philosophy, Meaning?]. But doing so doesn't make grue a legitimate word, let

alone a genuine one. Could there be such a word? That is, is naming the grue

concept truly unnatural, or merely unlikely?

Identifying systematic patterns governing the meanings of related words can provide

convincing answers to such questions. Furthermore, the insights go in two directions

simultaneously: on the one hand, natural classes of words that resemble each other

syntactically (for instance, the class of nouns) have similar kinds of meaning. This

places bounds on the set of possible word meanings. On the other hand, natural

classes of words that resemble each other semantically (for instance, the class of

words whose meanings involve the notion of causation) behave similarly from a

syntactic point of view. Thus studying how the fine-grained conceptual structure of a

words meaning interacts with the syntactic structures that contain it provides a

unique and revealing window into the nature of language, conceptualization, and

cognition.

Polysemy

Lexemes are linguistic items whose meaning cannot be fully predicted based on the

meaning of their parts. Idiomatic expressions by definition, then, are lexemes: the

expression kicked the bucket (as in the idiomatic interpretation of My goldfish kicked

the bucket last night) means essentially the same thing as the word died. (Incidentally,

although it is convenient to draw examples from English in this article, it gives an

unfortunate English-centric perspective to the discussion; those readers familiar with

agglutinative languages such as Turkish or West Greenlandic should consider whether

morpheme might be a more accurate term than word in the general case.) Other

articles in this encyclopedia discuss cases in which lexemes do not correspond exactly

to words [xref: Construction Grammar, Lexicon], but this article will adopt the

simplifying assumption that lexemes are words.

But how many distinct words are there? We can feel comfortable deciding that

HOMONYMS (words that sound the same but have completely different meanings)

should be counted as different lexical items: bat the flying mammal versus bat the

wooden stick used in baseball certainly ought to be considered as two different words.

It is more difficult to be confident of such judgments, however, when the two

meanings seem to be closely related. Is wave in reference to a beach a different

concept than wave in He experienced a wave of anger? What about verbal uses such

as The infant waved or The policeman waved us through? Words that have multiple

related but distinct meanings are POLYSEMOUS. Identifying and dealing with

polysemy is a hotly debated and difficult problem in lexical semantics.

Some polysemy seems to be at least partly systematic. Pustejovsky proposes that

language users rely on QUALIA, which are privileged aspects in the way they

conceptualize objects. The four main qualia are the object's constituent parts, its form

(including shape), its intended function, and its origin. Thus a fast car is fast with

respect to performing its intended function of transporting people, but fast food is fast

Copyright Macmillan Reference Ltd

23 May, 2001

Page 2

Encyclopedia of Cognitive ScienceAuthor Stylesheet

with respect to its origin. We can recognize the polysemy of fast as indeterminacy in

selection of the most relevant qualia, without needing to postulate two lexical entries

for fast, let alone two distinct kinds of fastness.

In addition, qualia provide a way to understand how to COERCE a conventional

meaning into a variety of extended meanings. In The ham sandwich at table 7 is

getting restless [spoken by one waiter addressing another in a restaurant], the ham

sandwich refers not to the material parts of the sandwich, but to the person involved in

specifying the sandwich's intended function (i.e., to be eaten by someone).

Lexical relations (meaning in relation to other words)

There are two main modes for exploring word meaning: in relation to other words

(this section), and in relation to the world (see below). The traditional method used in

dictionaries is to define a word in terms of other words. Ultimately, this strategy is

circular, since we must then define the words we use in the definition, and in their

definitions, until finally we must either run out of words or re-use one of the words

we are trying to define.

One strategy is to try to find a small set of SEMANTIC PRIMES: Wierzbicka

identifies on the order of 50 or so concepts (such as GOOD, BAD, BEFORE, AFTER,

I, YOU, PART, KIND...) that allegedly suffice to express the meaning of all words (in

any language). Whether this research program succeeds or not has important

implications for the nature of linguistic conceptualization.

In any case, speakers clearly have intuitions about meaning relations among words.

The most familiar relations are synonymy and antinomy. Two words are

SYNONYMS if they mean the same thing, e.g., filbert and hazelnut, board and plank,

etc. Two words are ANTONYMS if they mean opposite things: black and white, rise

and fall, ascent and descent, etc. One reason to think that it is necessary to recognize

antinomy as an indispensable component of grammatical descriptions is because at

most one member of each antynomous pair is allowed to occur with measure phrases:

tall is the opposite of short, and we can say Bill is 6 feet tall, but not *Tom is 5 feet

short.

Other major semantic lexical relations include HYPONYMY (names for subclasses:

terrier is a hyponym of dog, since a terrier is a type of dog), and MERONYMY

(names for parts: finger is a meronym of hand).

Words whose meanings are sufficiently similar in some respect are often said to

constitute a SEMANTIC FIELD, though this term is rarely if ever given a precise

definition. Terms such as red, blue, green, etc., are members of a semantic field

having to do with color.

Miller and associates have developed a lexical database called WordNet, a kind of

multidimentional thesaurus, in which these types of lexical relations are explicitly

encoded. Thus WordNet is an attempt to model the way in which a speaker

conceptualizes one kind of word meaning.

Copyright Macmillan Reference Ltd

23 May, 2001

Page 3

Encyclopedia of Cognitive ScienceAuthor Stylesheet

Denotation (meaning in relation to the world)

Defining words in terms of other words or concepts will only take us so far.

Language talks about the world, and ultimately, in order to know what a word like

horse or despair means, it is necessary to know something about the world. One way

of getting at the connection between meaning and the world is to consider TRUTH

CONDITIONS: what must the world be like in order for a given sentence to be true?

In general, words participate in most of the kinds of truth-conditional meaning that

sentences do, plus one or two more of their own.

ENTAILMENT is the most concrete aspect of meaning: one sentence entails another

just in case the truth of the first sentence is sufficient to guarantee the truth of the

second. For instance, the sentence I have four children entails the sentence I have at

least two children. We can extend this notion to words by assuming that one word

entails another just in case substituting one word in for the other in a sentence

produces an entailment relation. Thus assassinate entails kill, since Jones

assassinated the President entails Jones killed the President. Similarly, whisper

entails spoke, devour entails ate, and so on.

PRESUPPOSITIONS are what must already be assumed to be true in order for a use

of a sentence to be appropriate in the first place. For instance, and and but mean

almost the same thing, and differ only in the presence of a presupposition associated

with but. If I assert that Tom is rich and kind, it means exactly the same thing as Tom

is rich but kind as far as what Tom is like; the only difference is that the use of the

sentence containing but presupposes that it is unlikely for someone who is rich to also

be kind.

SELECTIONAL RESTRICTIONS are a kind of presupposition associated

exclusively with words. The verb sleep presupposes that its subject is capable of

sleeping; that is, it selects a restricted range of possible subjects. One reason why the

sentence *Green ideas sleep furiously is deviant, then, is because ideas are not

capable of sleeping, in violation of the selectional restriction of sleep.

IMPLICATURE is weaker than entailment. If you ask me how a student is doing in a

course, and I reply She's doing fine, I imply that she is not doing great (otherwise, I

would presumably have said so). Yet the sentence Shes doing fine does not entail the

sentence She's not doing great, since it can be true that a student is doing fine work

even if she is actually doing spectacular work. The implicature arises in this case

through contrast with other words that could have been used. Interestingly, such

lexical implicatures favor the formation of lexical gaps: because fine implicates not

good, there is no word that means exactly not good (for instance, mediocre entails

both not good and not bad). Similarly, because some implicates not all, there is no

single word (perhaps not in any language) that means exactly not all. [xref:

implicature]

CONNOTATION is the part of the meaning of a word that adds a rhetorical spin to

what is said. More specifically, connotation signals the attitude of the speaker

towards the object or event described. If I describe someone as garrulous rather than

talkative, the described behavior may be exactly the same, but garrulous conveys in

addition the information that I disapprove of or dislike the behavior in question.

Copyright Macmillan Reference Ltd

23 May, 2001

Page 4

Encyclopedia of Cognitive ScienceAuthor Stylesheet

VAGUENESS is perhaps the quintessential problem for scientific theories of word

meaning. Imagine a person with a full head of hair; clearly, this person is not bald.

Now imagine pulling out one hair at a time. Eventually, if this process is continued

long enough, the person will qualify as bald. But at what point precisely does the

switch from not-bald to bald occur? Its impossible to say for sure. But if we can't

answer this simple question, then how can we possibly claim to truly understand the

meaning of the word bald? A little reflection will reveal that virtually every word that

refers to objects or events in the real world contains vagueness: exactly how tuneless

must a verbal performance get before the claim She is singing is no longer true? Is

that short sofa really a chair? The pervasiveness and intractability of vagueness gives

rise to profound philosophical issues [xref Vagueness].

Kinds of words, kinds of meaning

One of the most important principles in lexical semantics (part of the heritage of

Richard Montague) is that words in the same syntactic class (e.g., noun, verb,

adjective, adverb, determiner, preposition, etc.) have similar meanings. That is, the

meaning of a determiner like every differs from the meaning of a verb like buy in a

way that is qualitatively different from the difference in meaning between two verbs

like buy and sell.

The overarching division in word classes distinguishes function words from content

words. Function words (determiners, prepositions, conjunctions, etc.) are shorter,

higher-frequency words that serve as syntactic glue to combine words into sentences.

Content words (nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs) carry most of the descriptive

payload of a sentence. In the sentence He asked me to give her a haircut, the content

words are asked, give, and haircut.

Semantically, function words are much closer to being able to be expressed as a

mathematical or logical function. We can write a rule that gives a good

approximation of the contribution of and to truth conditions in the following way: A

sentence of the form [S1 and S2] will be true just in case S1 is true and S2 is also

true. Thus the sentence It was raining and it was dark will be true just in case the

sentence It was raining is true and the sentence It was dark is also true.

Among function words, the meaning of determiners such as every, no, most, few,

some, etc. (but crucially excluding NP modifiers such as only) have been studied in

exquisite detail, especially from the point of view of their logical properties. One of

the most celebrated results is the principle of CONSERVATIVITY: given any

determiner D, noun N, and verb phrase VP, sentences of the form [D N VP] are

guaranteed to be semantically equivalent to sentences of the form [D N be N and VP].

For instance, if the sentence Most cars are red is true, then the sentence Most cars are

cars and are red is also true, and vice versa; similarly, Some cars are red is

equivalent to some cars are cars and are red, and so on. It is conjectured that every

determiner in every language obeys conservativity. These equivalences may seem so

obvious that it is hard to appreciate just how significant this generalization is; it may

help, therefore, to imagine a new determiner antievery as having a meaning such that

a sentence Antievery car is red means the same thing as `everything that is not a car is

red'. The claim is that there could be no such determiner in any natural language, i.e.,

Copyright Macmillan Reference Ltd

23 May, 2001

Page 5

Encyclopedia of Cognitive ScienceAuthor Stylesheet

antievery (or any determiner that violated conservativity) is an impossible thing for a

word to mean.

There is a class of lexemes whose behavior is especially fascinating from a cognitive

point of view. In English this class includes expressions such ever, anymore, budge

an inch, and many others. These items can only be used in sentences that exhibit

certain properties related to the presence of negation. For instance, it is possible to

say She doesn't ever go to the movies anymore, but it is impossible to say *She ever

goes to the movies anymore. It is the presence of the negation in the first sentence that

licenses the words in question, and it is because of this affinity for negation that they

are called NEGATIVE POLARITY ITEMS. Not only are NPIs interesting in their

own right, they provide clues about the internal structure of the meaning of other

words. Consider the following contrast: I doubt that she ever goes to the movies

anymore is fine, but *I think that she ever goes to the movies anymore is deviant.

Because negative polarity items are licensed by doubt but not by think, we can

conclude that the meaning of doubt contains negation hidden within it, so that doubt

means roughly think that not (i.e., think that it is not the case that).

Events

The main linguistically important divisions among event types are as follows:

Stage-level adjectives such as drunk correspond to temporary stages of an individual

rather than properties that are (conceived of as being) permanent properties of

individuals such as intelligent. Telic activities differ from atelic ones in having a

natural end point. Crucially, these semantic distinctions correspond to systematic

differences in syntactic behavior. For instance, assume that the temporal use of the

preposition for requires the absence of an endpoint, but in requires a definite end

point. If gaze is naturally atelic but built is telic, this explains why it is possible to say

He gazed out to sea for an hour but not *He gazed out to sea in an hour, and

conversely, why it is impossible to say *He built the raft for an hour at the same time

that He built the raft in an hour is perfectly fine.

Although many lexical predicates are naturally atelic or telic, the telicity of the

sentence in which they occur can be determined by other elements in the sentence.

For instance, some verbs (drink, write, draw, erase, pour, etc.) have meanings that

establish a systematic correspondence between the physical subparts of one of their

arguments and the described event. Consider the verb mow: the subparts of an event

of mowing the lawn correspond to the subparts of the lawn. If the event of mowing

the lawn is half over, then roughly half the lawn will have been mown. This contrasts

Copyright Macmillan Reference Ltd

23 May, 2001

Page 6

Encyclopedia of Cognitive ScienceAuthor Stylesheet

with a verb like interview: if an interview with the President is half over, that does not

mean that half of the President has been interviewed. Because of the systematic

correspondence between the internal structure of the NP denotation and the internal

structure of the described event, semantic properties of this special type of verbal

argument-NP (which is called an INCREMENTAL THEME) can project to determine

semantic properties of the described event. In particular, the telicity of sentences

containing incremental theme verbs depends on whether the incremental theme

argument is conceived of as quantized (a beer is quantized, compared with just beer):

John drank a beer in/*for an hour versus John drank beer for/*in an hour.

Thematic roles

Decomposition

Sentences have internal structure in which the basic unit is the word [xref: syntax].

For instance, the sentence The girl hit the boy has for its coarse-grained structure [[the

girl] [hit [the boy]]]. Words have internal structure as well, in which the basic unit is

the morpheme [xref: morphology]. For instance, undeniable = [un [deni [able]]]. Just

as the meaning of a sentence must be expressed as a combination of the meaning of its

parts and their syntactic configuration, we expect the meaning of a word (in the

normal case) to be a combination of the meanings of its parts, and indeed undeniable

means roughly not able to be denied. The internal structure of words can be quite

complex, as in agglutinative languages like Turkish, in which there is no principled

limit to the number of morphemes in a word.

Yet in general, word structure is qualitatively less complex than syntactic structure in

a variety of measurable ways. If the structure of word meaning mirrors the way in

which words are built up from morphemes, then we might also expect that word

meaning will be simpler than sentence meaning in some respects. However, as

discussed in the next section, many scholars believe that the meaning of words has

internal structure that does not correspond to any detectable morphological structure.

Argument structure and Conceptual structure

One of the main ways in which words in the same main syntactic class differ in their

syntax and in their meaning is in terms of argument structure. Fall, hit, give, and bet

are all verbs, but differ in the number and arrangement of noun phrase arguments they

occur with: intransitive verbs have one argument (John fell); transitive verbs have two

arguments (John hit the ball), and ditransitive verbs have three arguments (John gave

the book to Mary). Thus it is necessary to annotate each word with its ARGUMENT

STRUCTURE, and the meaning of the verb will refer to elements in the argument

structure.

CONCEPTUAL STRUCTURE defines the connection between argument structure

and meaning. According to Jackendoff, for example, the transitive verb drink

corresponds to the following (simplified) lexical entry:

Word:

drink, verb (transitive)

Argument structure: NPi, NPj

Copyright Macmillan Reference Ltd

23 May, 2001

Page 7

Encyclopedia of Cognitive ScienceAuthor Stylesheet

Conceptual structure: CAUSE (NPi, GO (NPj, TO (IN (MOUTH-OF (NPi)))))

In the sentence John drank the soda, then, NPi = John, NPj = the soda, and the

sentence as a whole means `John caused the soda to go into John's mouth'.

Note that the conceptual structure is considerably more complex than the syntactic

structure in which the verb participates: the concept named by drink has been

decomposed into five separate predicates (CAUSE, GO, TO, IN, and MOUTH-OF),

and there are three arguments at the conceptual level (John, the soda, and John's

mouth) instead of two, as at the overt syntactic level.

Levin and others show how separating conceptual structure from argument structure

provides a framework for explaining a type of polysemy that gives rise to various

syntactic ALTERNATIONS: cases in which a single word can be used with a variety

of argument structure configurations. The basic idea is that when a verb like break

occurs in a transitive sentence such as The girl broke the window, it has a conceptual

structure that explicitly involves causation (perhaps (CAUSE (THE-GIRL, BECOME

(BROKEN, THE-WINDOW)))). When the same verb occurs with a single argument,

as in the window broke, it takes for its conceptual meaning a proper subpart of the

transitive structure (i.e., (BECOME (BROKEN, THE-WINDOW))). Crucially, the

sub-structure omits mention of the causing entity.

A particularly interesting kind of alternation is known as an IMPLICIT ARGUMENT.

For instance, when comparing the meaning of John ate something versus John ate,

the omitted argument in the shorter version is intuitively still present conceptually. In

this case the two senses of eat differ only in argument structure but not in conceptual

structure.

Thematic roles and Linking

It is not an accident given the meaning of the word drink that the entity that causes the

drinking event is expressed as the subject of the sentence: in John drank the soda, we

know that John is consuming the soda, and not vice-versa. More generally, to some

degree at least, the meaning of verbs clearly interacts with the syntactic form of

sentences containing those verbs. The various theories developed to characterize the

connection between verb meaning and syntactic structure are called LINKING

THEORIES, and in many linking theories the connection depends on THEMATIC

ROLES. A verb like kiss, for instance, describes events that have two main

conceptual participants, which we can call the kisser (the entity that does the kissing)

and the kissee (the entity that gets kissed). When kiss occurs as the main verb in a

sentence of English, the kisser is always syntactically realized as the subject and the

kissee is realized as the direct object:

Syntactic structure:

[The girl]

Syntactic function:

Subject

Direct Object

Verb-specific roles:

kisser

kissee

Thematic roles:

Agent

Patient

Copyright Macmillan Reference Ltd

kissed

23 May, 2001

[the boy]

Page 8

Encyclopedia of Cognitive ScienceAuthor Stylesheet

Thus the linking rules for English must guarantee that the verb-specific kisser role

always comes to be associated with the grammatical subject of the sentence. (Passive

sentences such as the boy was kissed by the girl are a systematic variation on the basic

pattern in which the normal basic linking is deliberately reversed for discourse

purposes.)

Building on ideas of Davidson that emphasize the importance of events in the

semantics of verbs, Parsons accounts for linking regularities by providing thematic

roles as primitive notions, and stipulating that when a verb assigns an NP the role of

Agent, that NP must appear in subject position. The sentence Brutus stabbed Caesar

with a knife would be rendered as [STABBING(e) & AGENT (BRUTUS, e) &

PATIENT (CAESAR, e) & INSTRUMENT (KNIFE, e)], which asserts that e is a

stabbing event, Brutus is the agent of the stabbing event, Caesar is the patient, and the

knife is the instrument.

Other linking theories attempt to derive thematic roles from independently motivated

aspects of meaning. In a theory that recognizes conceptual structure, we can

hypothesize that for any verb that contains as part of its meaning the conceptual

primitive CAUSE, the first conceptual argument of the CAUSE predicate will be an

agent. Put another way, the hypothesis is that the syntactic subject is the participant

that the speaker conceptualizes as taking the more active causal role in the event.

Both the neo-Davidsonian approach and the conceptual structure approach rely on

defining the meaning of a word in terms of other more basic concepts. Dowty

approaches the issue from the point of view of the relation between word meaning and

the world. In particular, he suggests that it suffices to consider the entailments of the

verb in question. The verb kiss entails that the kisser participant must have lips, that

those lips must come in contact with the kissee participant, and the kisser must

intentionally cause the contact to occur. In contrast, it is not an entailment that the

kissee has lips, since it is perfectly possible to kiss a clam, or a rock, nor is there an

entailment that the kissee intentionally causes the kissing event to occur (imagine

kissing a sleeping child). On entailment-based theories of thematic roles, if a verb

entails that a participant intends for the event described by the verb to come about, or

causes it to come about, then that participant will (be more likely to) be expressed as

the subject rather than as the direct object. (Different but analogous claims apply to

linking in ergative languages.)

All theories that recognize the existence of thematic roles provide at least two basic

thematic roles: Agent and Patient (the term PATIENT is often collapsed with the term

THEME, whence the cover term thematic roles). Agents tend to be subjects;

patients, which are conceived of as undergoing an action (alternatively, are entailed to

undergo an action, or which are incremental themes) make good direct objects.

Among the other thematic roles that play a prominent part in many linking theories

are Experiencer, Source, Goal, and Instrument.

Linking theories make strong predictions about possible and impossible words.

Assume we are presented with a verb glarf that is allegedly a previously unknown

transitive verb of English. We are told the following concerning its meaning: it

describes situations in which one participant comes into violent contact with the foot

of another participant. Furthermore, we know that it is the participant that possesses

the foot who initiates or causes the touching event to occur. Now we encounter the

Copyright Macmillan Reference Ltd

23 May, 2001

Page 9

Encyclopedia of Cognitive ScienceAuthor Stylesheet

following sentence: The ball glarfed the player, which is used as a description of an

event in which a football player kicked a football for a field goal. (In other words,

glarf seems to be the verb kick but with subject and direct object reversed.) At this

point, we can conclude that glarf is not a legitimate word of English (and in fact, is

not a legitimate basic verb in any human language that recognizes the grammatical

relations of subject and object), because it associates the volitional participant with

the direct object and the more passive undergoer participant with the subject, contrary

to the predictions of linking theories.

In fact, thematic roles can provide insight even into the syntactic behavior of verbs

that have only one argument. The unaccusative hypothesis, due largely to Perlmutter,

was a breakthrough in the use of lexical semantics to explain syntactic patterns. The

hypothesis claims that intransitive verbs whose sole argument is semantically an

Agent (predicates like sing, smile, or walk) behave differently cross-linguistically than

so-called UNACCUSATIVE verbs, whose one argument is semantically a Patient

(e.g., fall, bleed, or sleep---crucially, these activities are conceived of as not being

done intentionally). For instance, unaccusative verbs in Italian generally take essere

as a past auxiliary rather than avare.

Like the correspondence between thematic roles and argument linking, the

unaccusativity pattern is systematic enough to be quite compelling. However, as with

virtually every attempt to derive syntactic behavior directly from semantic

distinctions, examination of a wider range of data has revealed a considerable number

of complications and exceptions. Nevertheless, there can be no doubt that meaning

and form are deeply and inextricably connected, and that lexical semantics is the place

at which they come into contact with one another. Therefore understanding lexical

semantics is critical to understanding the yin and yang of language and

conceptualization.

Further Reading

Dowty, David (1991) Thematic proto-roles and argument selection. Language

67.3:547--619.

Fellbaum, Christiane, ed. (1998) WordNet: An Electronic Lexical Database, MIT

Press.

Grimshaw, Jane (1990) Argument Structure. MIT Press.

Jackendoff, Ray (1990) Semantic Structures. MIT Press.

Kamp, Hans and Barbara Partee (1995) Prototype theory and compositionality.

Cognition 57:129--191.

Levin, Beth (1993) English Verb Classes and Alternations. A Preliminary

Investigation. The University of Chicago Press.

Levin, Beth and Steven Pinker, eds. (1990) Lexical and Conceptual Semantics.

Parsons, Terrance (1990) Events in the Semantics of English: A Study in Subatomic

Semantics. MIT Press.

Pustejovsky, James (1995) The Generative Lexicon. MIT Press.

Copyright Macmillan Reference Ltd

23 May, 2001

Page 10

Encyclopedia of Cognitive ScienceAuthor Stylesheet

Wierzbicka, Anna (1996) Semantics, Primes and Universals. Oxford University

Press.

Glossary

Alternation#A single verb or other predicate occuring in multiple distinct but

syntactically or semantically related constructions.

Argument Structure#The configuration of arguments syntactically required by a verb

or other predicate.

Conceptual Structure#The configuration of arguments conceptually requred by a verb

or other predicate.

Decomposition#Expression of a lexical meaning in terms of simpler concepts.

Denotation#Meaning in relation to the world.

Lexeme#Basic expression (typically a word, but possibily a morpheme, idiom, or

construction) with its own characteristic meaning.

Linking#The systematic correspondence between conceptual or semantic argument

types and their range of legitimate syntactic realizations.

Polysemy#having multiple distinct but related meanings.

Thematic Role#A characterization of a natural class of predicate argument positions

(e.g., the Thematic Role Agent putatively characterizes the subject argument of a

wide class of verbs).

Copyright Macmillan Reference Ltd

23 May, 2001

Page 11

You might also like

- A Study of Textual Metafunction Analysis in Melanie Martinez - 1Document4 pagesA Study of Textual Metafunction Analysis in Melanie Martinez - 1Cosmelo MacalangcomoNo ratings yet

- Mona Baker - Contextualization in Trans PDFDocument17 pagesMona Baker - Contextualization in Trans PDFBianca Emanuela LazarNo ratings yet

- Pub Bickerton On ChomskyDocument12 pagesPub Bickerton On ChomskyVanesa ConditoNo ratings yet

- Pe Lesson Plan 5 & 6 Tgfu Gaelic FootballDocument5 pagesPe Lesson Plan 5 & 6 Tgfu Gaelic Footballcuksam27No ratings yet

- English Written Proficiency Intermediate 1 - CoursebookDocument79 pagesEnglish Written Proficiency Intermediate 1 - CoursebookNguyễn ViệtNo ratings yet

- EssentialJapaneseGrammer PDFDocument491 pagesEssentialJapaneseGrammer PDFDennis Afandi93% (15)

- Semantics and Theories of Semantics PDFDocument15 pagesSemantics and Theories of Semantics PDFSriNo ratings yet

- First GlossaryDocument4 pagesFirst GlossaryStella LiuNo ratings yet

- Makalah Semantic1Document6 pagesMakalah Semantic1karenina21100% (1)

- Semantics and Theories of SemanticsDocument15 pagesSemantics and Theories of SemanticsAnonymous R99uDjYNo ratings yet

- Lecture 6. Lexical Meaning and Semantic Structure of English WordsDocument6 pagesLecture 6. Lexical Meaning and Semantic Structure of English WordsigorNo ratings yet

- SematicsDocument5 pagesSematicsDonmagreloNo ratings yet

- Discuss The Concept of Semantics and Elaborate NameDocument4 pagesDiscuss The Concept of Semantics and Elaborate NameAnonymous R99uDjYNo ratings yet

- Semantic and Pragmatic Courses: (Word Sense)Document6 pagesSemantic and Pragmatic Courses: (Word Sense)Widya NingsihNo ratings yet

- Nofsinger Invoking Alluded To Shared KnowledgeDocument16 pagesNofsinger Invoking Alluded To Shared KnowledgeidschunNo ratings yet

- Coherence in Discourse AnalysisDocument11 pagesCoherence in Discourse AnalysisYara TarekNo ratings yet

- Semantic Field Semantic Relation and SemDocument20 pagesSemantic Field Semantic Relation and SemLisa HidayantiNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Cognitive Linguistics 1 Truong Van Anh Sai Gon UniversityDocument51 pagesIntroduction To Cognitive Linguistics 1 Truong Van Anh Sai Gon UniversityCognitive LinguisticsNo ratings yet

- Summary Morphology Chapter 4Document10 pagesSummary Morphology Chapter 4Maydinda Ayu PuspitasariNo ratings yet

- Critics GenerativismDocument26 pagesCritics GenerativismIgor ArrésteguiNo ratings yet

- The Paper of Coherence in The Interpretation of DiscourseDocument19 pagesThe Paper of Coherence in The Interpretation of DiscoursemeymirahNo ratings yet

- PSychoyos Semiotica LibreDocument68 pagesPSychoyos Semiotica Librebu1969No ratings yet

- Gerald Steen, The Paradox of Metaphor WDocument30 pagesGerald Steen, The Paradox of Metaphor WnatitvzandtNo ratings yet

- 1 Lexicology PDFDocument14 pages1 Lexicology PDFbobocirina100% (2)

- ENG504 Important Topics For Terminal ExamDocument8 pagesENG504 Important Topics For Terminal ExamAnonymous SDpfNyMq7JNo ratings yet

- LEXICOLOGY GlossaryDocument6 pagesLEXICOLOGY GlossaryЖанна СобчукNo ratings yet

- Lexicology - Programa AnaliticaDocument7 pagesLexicology - Programa AnaliticaSilvia ȚurcanuNo ratings yet

- Syntax Introduction To LinguisticDocument6 pagesSyntax Introduction To LinguisticShane Mendoza BSED ENGLISHNo ratings yet

- Semantics Chapter 1Document12 pagesSemantics Chapter 1Милена СтојиљковићNo ratings yet

- Analysis Into Immediate Constituents. English LexicologyDocument8 pagesAnalysis Into Immediate Constituents. English LexicologyNicole Palada100% (1)

- Arnold - The English WordDocument43 pagesArnold - The English WordMariana TsiupkaNo ratings yet

- Akwa Ibom FestivalsDocument3 pagesAkwa Ibom FestivalsTemitayo SanusiNo ratings yet

- Ic TheoryDocument21 pagesIc Theoryyousfi100% (1)

- Four Aspects of His Theory (Except The Bilateral Model) SassureDocument24 pagesFour Aspects of His Theory (Except The Bilateral Model) SassureJafor Ahmed JakeNo ratings yet

- The Semiotic Triangle of meaningGROUPWDocument12 pagesThe Semiotic Triangle of meaningGROUPWMingue.pNo ratings yet

- Phraseological UnitsDocument9 pagesPhraseological UnitsТатьяна КройторNo ratings yet

- Updated August 02, 2018: Meaning or Semantic MeaningDocument2 pagesUpdated August 02, 2018: Meaning or Semantic MeaningDinda Hasibuan 005No ratings yet

- De Ning The WordDocument8 pagesDe Ning The Wordジョシュア ジョシュア100% (1)

- Department of EnglishDocument3 pagesDepartment of EnglishMuhammad Ishaq100% (1)

- 1.the Object and Aims of LexicologyDocument36 pages1.the Object and Aims of LexicologyАнастасия ЯловаяNo ratings yet

- Randal Whitman Teaching The Article in EnglishDocument11 pagesRandal Whitman Teaching The Article in EnglishdooblahNo ratings yet

- 1.concept of LanguageDocument19 pages1.concept of LanguageIstiqomah BonNo ratings yet

- What Is SemanticsDocument8 pagesWhat Is SemanticsSania MirzaNo ratings yet

- Semiotic TraditionDocument6 pagesSemiotic TraditionAngelica PadillaNo ratings yet

- Keywords. Lexeme, WFRS, Deverbal Nouns, Clipping, Delocutive AdverbsDocument20 pagesKeywords. Lexeme, WFRS, Deverbal Nouns, Clipping, Delocutive AdverbsSaniago DakhiNo ratings yet

- Self-Reference and Chaos in Fuzzy LogicDocument17 pagesSelf-Reference and Chaos in Fuzzy LogiccrisolarisNo ratings yet

- A Metaphor For GlobalizationfinalDocument6 pagesA Metaphor For Globalizationfinalapi-280184302100% (1)

- Semiotic TheoryDocument27 pagesSemiotic Theorynurdayana khaliliNo ratings yet

- Differences Between Oral and Written DiscourseDocument44 pagesDifferences Between Oral and Written DiscourseMj ManuelNo ratings yet

- Deep StructureDocument9 pagesDeep StructureLoreinNo ratings yet

- English Lexicology 2015Document270 pagesEnglish Lexicology 2015Rimvydė Katinaitė-MumėnienėNo ratings yet

- Language and CognitionDocument14 pagesLanguage and Cognitionnurul intanNo ratings yet

- KolokacijeDocument6 pagesKolokacijedule83No ratings yet

- Metaphors of Love in English and RussianDocument23 pagesMetaphors of Love in English and Russianthangdaotao100% (4)

- Nachos Study BookDocument109 pagesNachos Study BookNur Bahar YeashaNo ratings yet

- Saussure's Structural LinguisticsDocument10 pagesSaussure's Structural LinguisticsHerpert ApthercerNo ratings yet

- Clauses and SentencesDocument56 pagesClauses and Sentencesbbyk117100% (1)

- Kaplan, D. 1989, DemonstrativesDocument42 pagesKaplan, D. 1989, DemonstrativeskhrinizNo ratings yet

- The Problem of Polysemy in The English LanguageDocument41 pagesThe Problem of Polysemy in The English LanguageOgnyan Obretenov100% (2)

- Semiotics and PragmaticsDocument10 pagesSemiotics and Pragmaticsrogers michaelNo ratings yet

- Semantics PDFDocument13 pagesSemantics PDFsutraNo ratings yet

- HS Te17 0043Document7 pagesHS Te17 0043RavinduNo ratings yet

- Language & Literacy Development: PrincipalDocument2 pagesLanguage & Literacy Development: Principalcuksam27No ratings yet

- Verity Sparks Lost and FoundDocument2 pagesVerity Sparks Lost and Foundcuksam27No ratings yet

- Birthday Basket Order FormDocument1 pageBirthday Basket Order Formcuksam27No ratings yet

- 08 PragmaticsDocument3 pages08 Pragmaticscuksam27No ratings yet

- Renewable Energy An OverviewDocument8 pagesRenewable Energy An OverviewpeubrandaoNo ratings yet

- Before The Engine FiresDocument3 pagesBefore The Engine Firescuksam27No ratings yet

- Transition Element: The Use of Catalyst in IndustryDocument9 pagesTransition Element: The Use of Catalyst in Industrycuksam27No ratings yet

- Class Attendance RecordDocument1 pageClass Attendance Recordcuksam27No ratings yet

- Tag Games: A Resource Manual For Sport LeadersDocument12 pagesTag Games: A Resource Manual For Sport Leaderscuksam27No ratings yet

- Pe Lesson Plan 3 Tgfu Gaelic FootballDocument6 pagesPe Lesson Plan 3 Tgfu Gaelic Footballcuksam27No ratings yet

- (CLASSROOM ACTION RESEARCH) Reading Comprehension Through SQRW - KreasiDocument14 pages(CLASSROOM ACTION RESEARCH) Reading Comprehension Through SQRW - Kreasicuksam2783% (6)

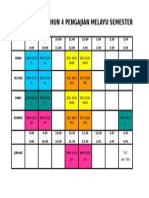

- Jadual Waktu Tahun 4 Pengajian Melayu Semester 2Document1 pageJadual Waktu Tahun 4 Pengajian Melayu Semester 2cuksam27No ratings yet

- Bride WarsDocument27 pagesBride Warscuksam27No ratings yet

- ECT - Games For Understanding FrameworkDocument10 pagesECT - Games For Understanding Frameworkcuksam27No ratings yet

- 17 Cambodia ModuleDocument5 pages17 Cambodia Modulecuksam27No ratings yet

- GAME - LineStrikeDocument1 pageGAME - LineStrikecuksam27No ratings yet

- The Malay Language in Malaysia and IndonesiaDocument21 pagesThe Malay Language in Malaysia and IndonesiaRaistz100% (10)

- Area: Games Unit: Football Resources: Balls, Bibs, Markers, ConesDocument1 pageArea: Games Unit: Football Resources: Balls, Bibs, Markers, Conescuksam27No ratings yet

- What Is SemanticsDocument8 pagesWhat Is Semanticscuksam27No ratings yet

- Prisoner of Azkaban Was Published On 8th July 1999 To Worldwide Acclaim and Spent Four Weeks at No.1Document2 pagesPrisoner of Azkaban Was Published On 8th July 1999 To Worldwide Acclaim and Spent Four Weeks at No.1cuksam27No ratings yet

- Entailment DenotationF10Document9 pagesEntailment DenotationF10cuksam27No ratings yet

- ISL PJM Anatomi Fisiologi Minggu 11 - JantungDocument4 pagesISL PJM Anatomi Fisiologi Minggu 11 - Jantungcuksam27No ratings yet

- Minggu 13 Peredaran DarahDocument11 pagesMinggu 13 Peredaran Darahcuksam27No ratings yet

- Meaning: Semantics and Pragmatics: Snow Hoax, When Rules Are Broken, Language in ContextDocument34 pagesMeaning: Semantics and Pragmatics: Snow Hoax, When Rules Are Broken, Language in Contextcuksam27No ratings yet

- 6 Most Common Mistakes in English SentencesDocument24 pages6 Most Common Mistakes in English SentencesAtmaNo ratings yet

- Japanese Grammar - 2Document23 pagesJapanese Grammar - 2valisblytheNo ratings yet

- Collocation in English and Arabic A Contrastive STDocument15 pagesCollocation in English and Arabic A Contrastive STاكرمونكوك كوولا koliqNo ratings yet

- Inglés Instrumental: Personal Pronouns and Possessive AdjectivesDocument4 pagesInglés Instrumental: Personal Pronouns and Possessive AdjectivesclaudiaNo ratings yet

- Adjective and Its TypesDocument7 pagesAdjective and Its TypesMuneeb ullah ShahNo ratings yet

- Sentence Structure - Part ThreeDocument6 pagesSentence Structure - Part ThreeAleja AmadoNo ratings yet

- Unit 8 Telling A Different StoryDocument54 pagesUnit 8 Telling A Different StoryAndres Sebastian Davila FalconesNo ratings yet

- Business English at Work: © 2003 Glencoe/Mcgraw-HillDocument41 pagesBusiness English at Work: © 2003 Glencoe/Mcgraw-HillSelfhelNo ratings yet

- Present Continuous Exercise 7 - CDocument3 pagesPresent Continuous Exercise 7 - CLlanca BlasNo ratings yet

- Speakout 3e B2 SBDocument18 pagesSpeakout 3e B2 SBvicky.noe19No ratings yet

- Syllables Worksheet Class 7Document3 pagesSyllables Worksheet Class 7hafsafayaz14No ratings yet

- Subject Verb Rules SeptDocument23 pagesSubject Verb Rules SeptMj ManuelNo ratings yet

- Foundation English PDF 3&4 Unit (Topics)Document56 pagesFoundation English PDF 3&4 Unit (Topics)Meer Bilal AliNo ratings yet

- Irregular Verbs: Present Past Tense Past Participle Gerund SpanishDocument3 pagesIrregular Verbs: Present Past Tense Past Participle Gerund SpanishAmador BarronNo ratings yet

- Adj AdvDocument25 pagesAdj AdvTheo Simon SulcaNo ratings yet

- Deutschkurs A1 PronunciationDocument6 pagesDeutschkurs A1 PronunciationHammad RazaNo ratings yet

- Topic: Auxiliary & Modal Verbs: Forms and FunctionsDocument18 pagesTopic: Auxiliary & Modal Verbs: Forms and FunctionsCarlos JulioNo ratings yet

- Syntax: Basic Verb PhraseDocument19 pagesSyntax: Basic Verb PhraseMaulana MualimNo ratings yet

- Aula #04 ParagraphsDocument41 pagesAula #04 Paragraphskiuwo bbopNo ratings yet

- UAS Morphology - Mario Fakhri Putra. ADocument17 pagesUAS Morphology - Mario Fakhri Putra. AIPNU IPPNU RANTING LENGKONGNo ratings yet

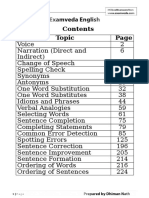

- Examveda Computer and EnglishDocument483 pagesExamveda Computer and EnglishGold LeafNo ratings yet

- Some of The Most Common Sentence Patterns: S-V S-V-O S-V-SC Rocks Explode.Document17 pagesSome of The Most Common Sentence Patterns: S-V S-V-O S-V-SC Rocks Explode.Marsa ArrahmanNo ratings yet

- Japanese GrammarDocument24 pagesJapanese GrammarJaycee Bareng PagadorNo ratings yet

- Passive LoathingDocument23 pagesPassive LoathingivanwkNo ratings yet

- Sentence ErrorDocument52 pagesSentence ErrorJąhąnząib Khąn KąkąrNo ratings yet

- EnglishDocument5 pagesEnglishSiti HajarNo ratings yet

- Word Structure - 2Document31 pagesWord Structure - 2Alshadaf FaidarNo ratings yet

- Name: Afrilia Kartika SRN/CLASS: 1803046006/PBI 5A: Basis For Comparis ON Syntax GrammarDocument5 pagesName: Afrilia Kartika SRN/CLASS: 1803046006/PBI 5A: Basis For Comparis ON Syntax GrammarAfrilia kartikaNo ratings yet