Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Surgical Vacuum Drains

Surgical Vacuum Drains

Uploaded by

obonk2880 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

13 views9 pagesjurnal

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documentjurnal

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

13 views9 pagesSurgical Vacuum Drains

Surgical Vacuum Drains

Uploaded by

obonk288jurnal

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 9

Surgical Vacuum Drains:

Types, Uses, and

Complications

RAJARAMAN DURAI, MD, MRCS; PHILIP C.H. NG, MD, FRCS

1.2

ABSTRACT

High- and low-pressure vacuum drains are commonly used after surgical procedures.

High-pressure vacuum drains (ie, sealed, closed-circuit systems) are efcient and

allow for easy monitoring and safe disposal of the drainage. Low-pressure vacuum

drains use gentle pressure to evacuate excess uid and air, and are easy for patients

to manage at home because it is easy to reinstate the vacuum pressure. Perioperative

nurses should be able to identify the various types of commonly used drains and their

surgical applications. Nurses should know how to care for drains, how to reinstate

the vacuum pressure when necessary, and the potential complications that could

result from surgical drain use. AORN J 91 (February 2010) 266-271. AORN, Inc,

2010

Key words: surgical drains, four-channel vacuum drains, low-pressure vacuum

drains, high-pressure vacuum drains, negative pressure.

D

rains are commonly used after surgical

procedures and can be classied as either

active or passive.

1

Active drains use neg-

ative pressure to remove accumulated uid from a

wound. Passive drains depend on the higher pres-

sure inside the wound in conjunction with capil-

lary action and gravity to draw uid out of a

wound (ie, the difference in pressure between the

inside and the outside of the wound forces the

uid out of the wound).

Passive drains, such as a Penrose drain, do not

require special attention; the dressing is changed

when it becomes saturated, or, if the drain is at-

tached to a reservoir, then the reservoir is emptied

or changed when it is full. Active drains, how-

ever, do require special maintenance. The collec-

tion reservoir of an active drain expands as it col-

lects uid drainage by exchanging negative

pressure for uid. The drain becomes ineffective

if the vacuum is lost. This article provides infor-

mation on the various types of commonly used

vacuum drains, nursing care of drains, methods to

reinstate a drains vacuum pressure, and potential

complications of drain use.

indicates that continuing education contact

hours are available for this activity. Earn the con-

tact hours by reading this article, reviewing the

purpose/goal and objectives, and completing the

online examination and learner evaluation at http://

www.aornjournal.org/ce. The contact hours for this

article expire February 28, 2013.

266 AORN Journal February 2010 Vol 91 No 2 AORN, Inc, 2010

USE OF DRAINS

Drains are used both prophylactically and thera-

peutically. The most common use is prophylactic

after surgery to prevent the accumulation of uid

(eg, blood, pus) or air. In any surgery in which a

dead space (eg, a cavity) is created, the body has

a natural tendency to ll this space with uid or

air. Use of a prophylactic drain is not routinely

recommended after clean surgical procedures,

2,3

although some articles claim that use of drains

results in seroma reduction,

4,5

and results of re-

search have shown that use of vacuum drains may

not inuence the outcome after tissue expander

use in breast surgery.

6

Surgical drains commonly

are used after procedures on the thyroid,

2

breast,

7

and axillary area as well as after abdominal pro-

cedures and joint replacements.

8,9

Vacuum drains

may be used to drain perirectal wounds,

10

and

certain special vacuum drains (ie, endoluminal)

are available to treat anastomotic leaks that may

occur after intestinal resection and anastomosis.

11,12

DRAIN INSERTION

Typically, when a drain is required, it is inserted

at the end of a surgical procedure. Frequently, the

drain is inserted through a separate hole a few

centimeters from the main incision to decrease the

risk of a postoperative wound infection. There are

two methods to insert a vacuum-type drain. The

rst method is used with drains that have a sharp

trocar attached to the tube. The surgeon uses the

trocar with some drains attached to pierce the

skin from the inside of the wound at the desired

site and pulls the attached tube out through the

stab wound. The surgeon places the inner end of

the tube at the required site and detaches the tro-

car. The surgeon may secure the drain to the skin

with a stay-stitch. After the wound is closed, the

scrub person connects the tube to the reservoir.

Suction may be attached to the reservoir to facili-

tate wound drainage.

The second method for drain insertion is used

when a trocar is not attached to the drainage tube.

In this case, the surgeon uses a forceps to pierce

the abdominal wall from the inside of the wound

and pushes the forceps through the subcutaneous

tissue. He or she then incises the overlying skin

with a scalpel. The surgeon opens the tip of the

forceps to grasp the end of the drain tube and

pulls the drain into the wound to the desired loca-

tion. The surgeon may secure the tube to the pa-

tients skin with a stay-stitch. The scrub person

connects the tube to the reservoir after the wound

is closed.

Vacuum drains are classied according to the

degree of pressure used. Typical bottled vacuum

drains (eg, Redi-vac) use high negative pressure.

Bulb-shaped suction devices (eg, Jackson-Pratt)

and collapsible four-channel vacuum drains (eg,

J Vac, Blake) use low negative pressure.

HIGH-NEGATIVE-PRESSURE DRAINS

High-pressure bottled vacuum drains have the

advantages of being sealed, closed-circuit systems

that allow for easy monitoring and safe disposal

of the drainage. These systems consist of a clear,

plastic reservoir with a rubber cap that has indica-

tor wings to monitor the presence of vacuum

pressure and an opening in which to connect the

drainage tube. When a vacuum is present in the

system, the wings on the rubber cap are close

together; the wings are apart if the vacuum is

lost. The end of the drainage tube that is inserted

into the wound has multiple openings on its inner

side through which uid can be evacuated from

the wound. The wound should be closed before

the clamps on the drain are opened; otherwise the

vacuum will be lost as the tube sucks in atmo-

spheric air.

Although the patients condition and type of

surgical procedure indicate appropriate monitoring

times and documentation of drainage volumes, the

amount of drainage typically is measured two to

four hours after surgery and every six hours

thereafter. Occasionally, the surgeon may decide

to clamp the tube for a couple of hours if it

drains too much (eg, more than 100 mL an

hour).

13

This may occur after some procedures,

SURGICAL VACUUM DRAINS www.aornjournal.org

AORN Journal 267

such as joint replacements. Once every 24 hours,

the nurse should mark the drainage reservoir bot-

tle and record the volume of drainage collected in

24 hours.

Reinstating Vacuum Pressure

When the vacuum is lost, the drain will not func-

tion, so the tube has to be connected to a new

bottle or the vacuum must be reinstated by one of

the following methods. A clinician removes the

bottle from the drainage tube and loosens the

plastic attachment. In method #1 (ie, the suction-

tube method), the clinician connects the plastic

tube of the suction machine to the white plastic

attachment of the vacuum bottle and turns on the

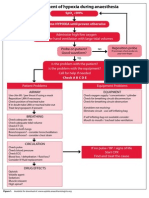

suction machine (Figure 1). In method #2 (ie, the

reverse Yankauer suction method), the clinician

inserts the tip of a Yankauer suction catheter into

the suction machine tube. The clinician then holds

the connection end of the Yankauer suction cathe-

ter tightly against the white plastic attachment of

the vacuum bottle and turns on the suction ma-

chine. In both methods, when the rubber cap

shows evidence of enough vacuum pressure in the

bottle, the clinician clamps the plastic attachment

on the drainage tube to retain the vacuum pres-

sure, then the clinician disconnects the suction

machine tubing.

LOW-NEGATIVE-PRESSURE DRAINS

Low-pressure vacuum drains have a plastic bulb-

shaped reservoir and a silicone drainage tube,

with multiple side holes at the end that is inserted

into the wound. When the bulb is compressed, air

is forced out, which creates negative pressure in

the system. Low-negative-pressure drains work

gently to evacuate excess uid and air.

It is easy to educate the patient so that he or

she can care for a bulb-type, low-pressure vac-

uum drain at home without help. Removing the

plug from the exit valve allows the bulb to in-

ate. The amount of drainage is easily quantied

with the measurement marks on the side of the

bulb. The patient empties the contents into a dis-

posable container or cup by squeezing the bulb

reservoir, then the patient squeezes the bulb again

and replaces the cap, thus recreating the negative

pressure. The patient can also be instructed on

Figure 1. One method to reinstate the pressure in a

high-pressure bottled vacuum drain is to attach the

plastic tube (arrow) to the suction unit and then

release and close the valve when appropriate.

Figure 2. A four-channel vacuum drain ready for

insertion.

February 2010 Vol 91 No 2 DURAING

268 AORN Journal

how to remove the drain at home without assis-

tance, if necessary.

A four-channel vacuum drain is a type of low-

pressure drain; the primary difference is the size

and shape of the reservoir.

14

The drain tube is

soft and exible,

15

and the reservoir is foldable

with two outlets (Figure 2). One outlet is used for

connecting to two drains and another outlet is

used for emptying the contents. The drainage tube

has four tiny lumina that join to form a single

lumen. The advantage of a four-channel vacuum

drain is that it is unlikely to become occluded by

the omentum because of the tiny size of the

holes. The disadvantage is that the holes may not

be large enough to evacuate larger particles of

tissue or blood clots.

After the surgeon inserts the drain by using

one of the two methods previously described, the

scrub person connects the drain tube to the outlet

adaptor. The scrub person folds or bends the res-

ervoir into a U shape by pressing both thumbs on

the marked areas in the middle part of the reser-

voir, which releases the locking system (Figure

3). The scrub person removes the plug from the

exit valve and repeats the procedure by bending

the reservoir to create vacuum pressure. The

scrub person then reseals the reservoir with the

plug. The scrub person may have to repeat this

process several times until all the air is removed

from the reservoir. On the postoperative nursing

unit, the nurse monitors drain output and empties

the reservoir when required. A vacuum is easily

visible by the undistended or unfolded appearance

of the reservoir. The bag will appear larger when

the vacuum is lost.

DRAIN REMOVAL

The negative pressure in the reservoir should be

released by removing the plug from the exit

valve, and the bulb or reservoir should be discon-

nected before the drain is removed. After cutting

the stay-stitch, if there is one, the nurse or patient

smoothly pulls out the drain. Drain removal can

be painful for some patients, so the patient may

wish to take an oral analgesic before removing

the drain. After removing the drain, the nurse or

patient should clean the drain-tube site with anti-

septic and a small dry cotton swab. If the site is

oozing, then the nurse can apply a gauze dressing.

If there is a large quantity of drainage, then the

nurse can apply a stoma bag.

COMPLICATIONS OF VACUUM DRAINS

Although drains serve an important function, there

are potential complications with their use. Some of

these complications include the following:

BreakageDrains are made of strong silicone

or polyvinyl chloride plastic and, therefore,

are not likely to break, but breakage can oc-

cur.

16

Laparoscopy may be required if part of

a drain breaks off inside the patients abdo-

men during removal.

17

Figure 3. To use a four-channel vacuum drain, the

clinician bends the reservoir into a U by pressing

both thumbs on the marked spots to release the

lock.

SURGICAL VACUUM DRAINS www.aornjournal.org

AORN Journal 269

Difculty in removalIf a drain remains in-

serted for a long period of time, it may be-

come difcult to remove. On occasion, the

drain has been stitched to the wound during

closure of deeper layers. The nurse should

report any difculty encountered during drain

removal to the surgeon. The wound may need

to be temporarily opened to remove the drain.

Inadvertent removalDrains may get tangled

in the patients other lines (eg, IV tubing,

electrocardiogram leads) or become tangled in

clothing or linen and accidentally be pulled

out. This might cause bleeding or pain.

InfectionAlthough one purpose of surgical

drains is to evacuate excessive uid accumula-

tion to prevent bacterial proliferation, drains

can increase the risk of infection via retro-

grade bacterial migration. Typically, drains are

removed when they are draining a negligible

amount (eg, less than 25 mL per day; less

than 1 mL per hour) to minimize this risk.

OcclusionDrain tubes can become occluded

by blood clot, tissue, or the omentum. This can

lead to the formation of a hematoma and subse-

quent discomfort and increased risk for infection.

PainDrain sites can be painful and may pre-

vent the patient from lying on the side where the

drain is inserted. Furthermore, some patients are

apprehensive about moving with a drain in place

after surgery; lack of movement can potentially

increase the risk of postoperative immobility

complications (eg, venous thrombosis).

Unsightly scarA drain site is left to heal by

secondary intention so the site may form a

puckering scar. When possible, the surgeon

may place the drain in a skin crease to help

improve cosmesis.

18

Visceral perforationDrains left in place for a

long period of time can erode into the bowel

and lead to visceral perforation.

19

SUMMARY

Perioperative nurses need to know the surgical

uses of high- and low-pressure vacuum drainage

systems as well as potential complications of sur-

gical drain use. Understanding how to create the

negative pressure vacuum will help nurses pro-

vide better drain care and better patient education.

Knowing how to recreate the negative pressure in

a high-pressure reservoir is particularly useful

when an underlled high-pressure vacuum drain

bottle loses its vacuum pressure. Low-pressure

vacuum drains have the advantages of easy emp-

tying and easy recreation of the gentle, negative

low-pressure vacuum, and they are easy for pa-

tients to manage at home.

Editors note: Redi-vac is a trademark of

Atrium Medical, Hudson, NH. Jackson-Pratt is

a registered trademark of Cardinal Health, Dub-

lin, OH. J Vac and Blake are registered

trademarks of Ethicon, St Louis, MO.

References

1. Durai R, Mownah A, Ng PC. Use of drains in surgery:

a review. J Perioper Pract. 2009;19(6):180-186.

2. Suslu N, Vural S, Oncel M, et al. Is the insertion of

drains after uncomplicated thyroid surgery always nec-

essary? Surg Today. 2006;36(3):215-218.

3. Kumar M, Yang SB, Jaiswal VK, Shah JN, Shreshtha

M, Gongal R. Is prophylactic placement of drains nec-

essary after subtotal gastrectomy? World J Gastroen-

terol. 2007;13(27):3738-3741.

4. Ismail M, Garg M, Rajagopal M, Garg P. Impact of

closed-suction drain in preperitoneal space on the inci-

dence of seroma formation after laparoscopic total ex-

traperitoneal inguinal hernia repair. Surg Laparosc En-

dosc Percutan Tech. 2009;19(3):263-266.

5. Chowdri NA, Qadri SA, Parray FQ, Gagloo MA. Role

of subcutaneous drains in obese patients undergoing

elective cholecystectomy: a cohort study. Int J Surg.

2007;(6):404-407. Epub June 8, 2007.

6. McCarthy CM, Disa JJ, Pusic AL, Mehrara BJ, Cord-

eiro PG. The effect of closed-suction drains on the inci-

dence of local wound complications following tissue

expander/implant reconstruction: a cohort study. Plast

Reconstr Surg. 2007;119(7):2018-2022.

7. Barton A, Blitz M, Callahan D, Yakimets W, Adams

D, Dabbs K. Early removal of postmastectomy drains is

not benecial: results from a halted randomized con-

trolled trial. Am J Surg. 2006;191(5):652-656.

8. Sundaram RO, Parkinson RW. Closed suction drains do

not increase the blood transfusion rates in patients un-

dergoing total knee arthroplasty. Int Orthop. 2007;31

(5):613-616. Epub September 1, 2006.

9. Kumar S, Penematsa S, Parekh S. Are drains required

following a routine primary total joint arthroplasty? Int

Orthop. 2007;31(5):593-596. Epub October 11, 2006.

February 2010 Vol 91 No 2 DURAING

270 AORN Journal

10. Durai R, Ng PC. Perirectal abscess following procedure

for prolapsed haemorrhoids successfully managed with

a combination of VAC sponge and Redivac systems.

Tech Coloproctol. 2009;13(4):307-309. Epub July 14,

2009.

11. Weidenhagen R, Gruetzner KU, Wiecken T, Spelsberg

F, Jauch KW. Endoluminal vacuum therapy for the

treatment of anastomotic leakage after anterior rectal

resection. Rozhl Chir. 2008;87(8):397-402.

12. Richterich JP, Heigl A, Muff B, Luchsinger S,

Gutzwiller JP. Endo-SPONGE: a new endoscopic treat-

ment option in colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;

68(5):1019-1022. Epub June 4, 2008.

13. Brueggemann PM, Tucker JK, Wilson P. Intermittent

clamping of suction drains in total hip replacement re-

duces postoperative blood loss: a randomized, con-

trolled trial. J Arthroplasty. 1999;14(4):470-472.

14. Tsuda Y, Takemura T, Shimamura Y, Iwasa S. Useful-

ness of silicone Blake drains after cardiac surgery [in

Japanese]. Kyobu Geka. 2003;56(12):1017-1019.

15. Rayatt SS, Dancey AL, Jaffe W. Soft uted silicone

drains: a prospective, randomized, patient-controlled

study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;115(6):1605-1608.

16. Campbell W, Wallace W, Gibson E, McCallion K.

Intra-abdominal drain fracture following pancreatic ne-

crosectomy. Ir J Med Sci. Epub ahead of print April 9,

2009.

17. Bharathan R, Dexter S, Hanson M. Laparoscopic re-

trieval of retained Redivac drain fragment. J Obstet

Gynaecol. 2009;29(3):263-264.

18. Dhar V, Townsley R, Black M, Laccourreye O. Thy-

roid surgery: the sub-mental drain. J Laryngol Otol.

2009;123(7):786. Epub October 17, 2008.

19. Carter P. Perforation of the bowel by suction drains.

Br J Surg. 1993;80(1):129.

Rajaraman Durai, MD, MRCS, is a specialist

registrar at University Hospital Lewisham,

London, UK. Dr Durai has no declared aflia-

tion that could be perceived as a potential con-

ict of interest in publishing this article.

Philip C.H. Ng, MD, FRCS, is a consultant

surgeon for the Department of Surgery at Uni-

versity Hospital Lewisham, London, UK.

Dr Ng has no declared afliation that could be

perceived as a potential conict of interest in

publishing this article.

SURGICAL VACUUM DRAINS www.aornjournal.org

AORN Journal 271

CONTINUING EDUCATION PROGRAM

1.2

Surgical Vacuum Drains: Types,

Uses, and Complications

PURPOSE

To educate perioperative nurses about the use of surgical vacuum drains.

OBJECTIVES

1. Differentiate between passive and active drains.

2. Identify uses of surgical drains.

3. Discuss how drains are inserted.

4. Explain how to reinstate vacuum pressure.

5. Describe low-pressure vacuum drains.

6. Identify complications associated with drain use.

The Examination and Learner Evaluation are printed here for your convenience. To

receive continuing education credit, you must complete the Examination and

Learner Evaluation online at http://www.aorn.org/CE.

QUESTIONS

1. Passive drains

a. use negative pressure to remove accumulated

uid from a wound.

b. depend on the higher pressure inside the

wound in conjunction with capillary action and

gravity to draw uid out of a wound.

c. use the sodium-potassium pump to exchange

sodium ions across the cell membrane with

potassium, which draws uid out of the

wound.

2. The collection reservoir of an active drain ex-

changes negative pressure for uid, so if the vac-

uum is lost, the drain becomes ineffective.

a. true b. false

3. The most common use of drains is to

a. introduce medication such as antibiotics into

the surgical wound after surgery.

b. decrease postoperative pain.

c. prevent the accumulation of uid or air

postoperatively.

d. monitor pressure inside the wound.

4. Use of a prophylactic drain is routinely recom-

mended after clean surgical procedures.

a. true b. false

5. When a surgeon inserts a drain with an attached

trocar, he or she pierces the skin from the outside

of the wound at the desired site and pulls the at-

tached tube in through the stab wound.

a. true b. false

EXAMINATION

272 AORN Journal February 2010 Vol 91 No 2 AORN, Inc, 2010

6. When a surgeon inserts a drain without an at-

tached trocar, the surgeon

1. uses a forceps to pierce the abdominal wall

from the inside of the wound.

2. pushes the forceps through the subcutaneous

tissue.

3. incises the overlying skin with a scalpel.

4. grasps the end of drain tube with the forceps

and pulls it into the wound.

5. secures the tube to the patients skin with a

stay-stitch.

a. 2 and 3 b. 1, 4, and 5

c. 2, 3, 4, and 5 d. 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5

7. If vacuum pressure is lost in a high-pressure bot-

tled vacuum drain, the vacuum can be reinstated

by using the ___________________ method.

1. reverse Yankauer suction

2. suction camshaft

3. suction tube

4. inversion suction

a. 1 and 3 b. 2 and 4

c. 1, 2, and 3 d. 1, 2, 3, and 4

8. The advantages of bulb-type, low-pressure vac-

uum drains include that

1. they can easily be cared for by the patient at

home without help.

2. the amount of drainage is easy to quantify.

3. the patient can be instructed on how to remove

the drain without assistance at home.

4. they work gently to evacuate excess uid and

air.

a. 1 and 2 b. 3 and 4

c. 1, 2, and 3 d. 1, 2, 3, and 4

9. The advantage of a four-channel vacuum drain is

that it

a. can evacuate larger particles of tissue or blood

clots.

b. can be used in multiloculated cavities.

c. is unlikely to become occluded by the

omentum.

d. has a higher negative-pressure vacuum.

10. Potential complications of drain use include

1. breakage or occlusion.

2. difcult or inadvertent removal.

3. electrolyte imbalance.

4. infection.

5. pain or unsightly scar.

6. visceral perforation.

a. 1, 3, and 5 b. 2, 3, 4, and 6

c. 1, 2, 4, 5, and 6 d. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6

The behavioral objectives and examination for this program were prepared by Rebecca Holm, RN, MSN, CNOR, clinical editor,

with consultation from Susan Bakewell, RN, MS, BC, director, Center for Perioperative Education. Ms Holm and Ms Bakewell

have no declared afliations that could be perceived as potential conicts of interest in publishing this article.

CE EXAMINATION www.aornjournal.org

AORN Journal 273

CONTINUING EDUCATION PROGRAM

1.2

Surgical Vacuum Drains: Types,

Uses, and Complications

T

his evaluation is used to determine the extent to

which this continuing education program met

your learning needs. Rate the items as described

below.

OBJECTIVES

To what extent were the following objectives of this

continuing education program achieved?

1. Differentiate between passive and active

drains. Low 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. High

2. Identify uses of surgical drains.

Low 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. High

3. Discuss how drains are inserted.

Low 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. High

4. Explain how to reinstate vacuum pressure.

Low 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. High

5. Describe low-pressure vacuum drains.

Low 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. High

6. Identify complications associated with drain

use. Low 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. High

CONTENT

7. To what extent did this article increase your

knowledge of the subject matter?

Low 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. High

8. To what extent were your individual objectives

met? Low 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. High

9. Will you be able to use the information from

this article in your work setting? 1. Yes 2. No

10. Will you change your practice as a result of

reading this article? (If yes, answer question

#10A. If no, answer question #10B.)

10A. How will you change your practice (Select all

that apply)

1. I will provide education to my team regard-

ing why the change is needed.

2. I will work with management to change

and/or implement a policy and procedure.

3. I will plan an informational meeting with

physicians to seek their input and acceptance

of the need for the change.

4. I will implement the change and evaluate the

effect of the change at regular intervals until

the change is incorporated as best practice.

5. Other:

10B. If you will not change your practice as a result

of reading this article, why? (Select all that

apply)

1. The content of the article is not relevant to

my practice.

2. I do not have enough time to teach others

about the purpose of the needed change.

3. I do not have management support to make a

change.

4. Other:

11. Our accrediting body requires that we verify the

time you needed to complete the 1.2 continuing

education contact hour (72-minute) program:

This program meets criteria for CNOR and CRNFA recertication, as well as other continuing education requirements.

AORN is accredited as a provider of continuing nursing education by the American Nurses Credentialing Centers Commission on Accreditation.

AORN recognizes these activities as continuing education for registered nurses. This recognition does not imply that AORN or the American Nurses Credentialing Center

approves or endorses products mentioned in the activity.

AORN is provider-approved by the California Board of Registered Nursing, Provider Number CEP 13019. Check with your state board of nursing for acceptance of this

activity for relicensure.

Event: #10007; Session: #4000 Fee: Members $6, Nonmembers $12

The deadline for this program is February 28, 2013.

A score of 70% correct on the examination is required for credit. Participants receive feedback on incorrect answers. Each

applicant who successfully completes this program will be able to print a certicate of completion.

LEARNER EVALUATION

274 AORN Journal February 2010 Vol 91 No 2 AORN, Inc, 2010

You might also like

- Sarrafian's Anatomy - Foot & Ankle - 3rdDocument779 pagesSarrafian's Anatomy - Foot & Ankle - 3rdOrto Mesp100% (16)

- ADD-00058826 ARCHITECT CC-IA Traceability Uncertainty Brochure PDFDocument21 pagesADD-00058826 ARCHITECT CC-IA Traceability Uncertainty Brochure PDFhm07100% (2)

- Surgical Wound ClassificationDocument1 pageSurgical Wound Classificationgeclear323No ratings yet

- The Newcastle Upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust Count ProcedureDocument42 pagesThe Newcastle Upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust Count ProcedureGina AprianaNo ratings yet

- Apraxia TreatmentDocument80 pagesApraxia Treatmentaalocha_25100% (1)

- Suction Machine: Surgical Students 5 Semester 5 BatchDocument12 pagesSuction Machine: Surgical Students 5 Semester 5 BatchIhteshamNo ratings yet

- Intraoperative CareDocument5 pagesIntraoperative CareraffineeNo ratings yet

- Catalago de AspiradoresDocument20 pagesCatalago de AspiradoresGomez, Francisco (AJR)No ratings yet

- Suction Machine GuidelinesDocument3 pagesSuction Machine GuidelinesSandip RajpurohitNo ratings yet

- Thoracic TraumaDocument24 pagesThoracic TraumaOmar MohammedNo ratings yet

- Minimal Invasive Surgery, Robotic, Natural Orifice Transluminal EndoscopicDocument59 pagesMinimal Invasive Surgery, Robotic, Natural Orifice Transluminal EndoscopicKahfi Rakhmadian KiraNo ratings yet

- Mastectomy/ Modified Radical Mastectomy: IndicationsDocument6 pagesMastectomy/ Modified Radical Mastectomy: IndicationsNANDAN RAINo ratings yet

- Skin Integrity and Wound CareDocument47 pagesSkin Integrity and Wound CareCHALIE MEQUNo ratings yet

- Foley Catheter CareDocument6 pagesFoley Catheter Carefreddie27No ratings yet

- Ecmo Review 2Document11 pagesEcmo Review 2Anonymous ZUaUz1wwNo ratings yet

- Orthopedic EmergenciesDocument75 pagesOrthopedic EmergenciesAlex beharuNo ratings yet

- Surgical DrainsDocument2 pagesSurgical DrainsSalim Mwaffaq AlhalholyNo ratings yet

- Staged Abdominal Re-Operation For Abdominal TraumaDocument7 pagesStaged Abdominal Re-Operation For Abdominal TraumaNovrianda Eka PutraNo ratings yet

- Facial InjuriesDocument61 pagesFacial InjuriesafifrspmNo ratings yet

- Surgical Infections Surgical Infections: HistoryDocument7 pagesSurgical Infections Surgical Infections: Historyjc_sibal13No ratings yet

- Adaptability (CS) - WPS OfficeDocument21 pagesAdaptability (CS) - WPS OfficeMalde KhuntiNo ratings yet

- Ot PDFDocument27 pagesOt PDFZain ShariffNo ratings yet

- Alterations in The Surgical Patient Updated 2010Document122 pagesAlterations in The Surgical Patient Updated 2010zorrotranNo ratings yet

- Cardiac Monitor, ECG and CauterizationDocument28 pagesCardiac Monitor, ECG and CauterizationGlaiza Mae Olivar-ArguillesNo ratings yet

- Supraglottic Airway Devices A Review in A New Era of Airway Management 2155 6148 1000647Document9 pagesSupraglottic Airway Devices A Review in A New Era of Airway Management 2155 6148 1000647Riris SihotangNo ratings yet

- History of FluorosDocument2 pagesHistory of FluorosEvi DianNo ratings yet

- Management of Hypoxia During AnaesthesiaDocument5 pagesManagement of Hypoxia During AnaesthesiaNurhafizahImfista100% (1)

- Ivc FilterDocument15 pagesIvc FilterashishNo ratings yet

- Atls SpineDocument11 pagesAtls SpineRonald David EvansNo ratings yet

- Operating TheatreDocument26 pagesOperating TheatreStephen Pilar PortilloNo ratings yet

- Initial Assessment and ManagementDocument8 pagesInitial Assessment and ManagementAlvin De LunaNo ratings yet

- Suction SystemsDocument11 pagesSuction SystemscatatanNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Trauma: LSU Medical Student Clerkship, New Orleans, LADocument31 pagesIntroduction To Trauma: LSU Medical Student Clerkship, New Orleans, LAnandangNo ratings yet

- Fumigation in Operation TheatresDocument22 pagesFumigation in Operation TheatresUtkarsh RaiNo ratings yet

- Surgical Drains and TubesDocument3 pagesSurgical Drains and TubesYusra ShaukatNo ratings yet

- 03 Anaesthesia Machine PDFDocument0 pages03 Anaesthesia Machine PDFjuniorebindaNo ratings yet

- Liver Segments Explained With MnemonicDocument13 pagesLiver Segments Explained With Mnemonicmyat252100% (1)

- 2020-07-07 Reconstructive Ladder FlapDocument96 pages2020-07-07 Reconstructive Ladder FlapTonie AbabonNo ratings yet

- 15Document21 pages15Tyson Easo JonesNo ratings yet

- AERB Guidelines RadiologyDocument4 pagesAERB Guidelines RadiologyTejinder100% (1)

- Percutaneous Nephrostomy: Last Updated: January 3, 2003Document5 pagesPercutaneous Nephrostomy: Last Updated: January 3, 2003Alicia EncinasNo ratings yet

- Post Op CareDocument7 pagesPost Op CareJeraldien Diente TagamolilaNo ratings yet

- Type of DialysisDocument11 pagesType of DialysisGail Leslie HernandezNo ratings yet

- Aspirador QuirurgicoDocument20 pagesAspirador QuirurgicoStanley LozaNo ratings yet

- Infection Control in ORDocument10 pagesInfection Control in ORaaminah tariqNo ratings yet

- Basic Chest X-Ray Interpretation (5minutes Talk) : DR - Alemayehu (ECCM R1)Document35 pagesBasic Chest X-Ray Interpretation (5minutes Talk) : DR - Alemayehu (ECCM R1)Alex beharuNo ratings yet

- Flap Reconstruction of The Abdominal WallDocument8 pagesFlap Reconstruction of The Abdominal WallDian AdiNo ratings yet

- Sudan Communicable Disease ProfileDocument123 pagesSudan Communicable Disease ProfileGalaleldin AliNo ratings yet

- Report in Respiratory SuctioningDocument29 pagesReport in Respiratory SuctioningWendy EscalanteNo ratings yet

- Post Cardiac Arrest CareDocument20 pagesPost Cardiac Arrest CareJayita Gayen Dutta100% (1)

- Mic Cabg Procedure PDFDocument12 pagesMic Cabg Procedure PDFprofarmah6150No ratings yet

- Atls MedscapeDocument5 pagesAtls MedscapeCastay GuerraNo ratings yet

- Ot PDFDocument11 pagesOt PDFAnukrit McgregorNo ratings yet

- 06 List of Day Care ProceduresDocument4 pages06 List of Day Care Proceduresanurag1309No ratings yet

- Planning An Operation Theatre ComplexDocument4 pagesPlanning An Operation Theatre ComplexRaviraj PisheNo ratings yet

- Pneumatic Tube Systems For Hospitals Englisch LowDocument5 pagesPneumatic Tube Systems For Hospitals Englisch LowVincent P Nam100% (1)

- Pneumonectomy Management PDFDocument6 pagesPneumonectomy Management PDFMurali BalaNo ratings yet

- Intravenous CannulationDocument9 pagesIntravenous CannulationjeorjNo ratings yet

- Anterior AbdominalDocument9 pagesAnterior AbdominalTAMBAKI EDMONDNo ratings yet

- Mesentric IschemiaDocument27 pagesMesentric Ischemiawalid ganodNo ratings yet

- Indications of JP DrainsDocument9 pagesIndications of JP DrainsDelbrynth MitchaoNo ratings yet

- Wound Drain Tube Management v2Document17 pagesWound Drain Tube Management v2PriyaNo ratings yet

- Care of DrainsDocument28 pagesCare of DrainschandhomepcNo ratings yet

- Electrical in Medical LocationDocument32 pagesElectrical in Medical LocationengrrafNo ratings yet

- Beat Tonsil BookDocument19 pagesBeat Tonsil BookXheni MeleNo ratings yet

- Auratus Hybrid Striped Bass, Morone Hybrid Saxatilis M. Chrysops and Ocellated River Stingray, Potamotrygon MotoroDocument7 pagesAuratus Hybrid Striped Bass, Morone Hybrid Saxatilis M. Chrysops and Ocellated River Stingray, Potamotrygon MotoroMiguel Ángel Gallego DomínguezNo ratings yet

- Northern Trust - Whiteabbey Hospital Site PlanDocument1 pageNorthern Trust - Whiteabbey Hospital Site PlanFloyd PriceNo ratings yet

- OBG Picture Based Discussion 01Document48 pagesOBG Picture Based Discussion 01Dheeraj Nandal0% (1)

- American Society of Hematology 2018 Guidelines For Management of Venous Thromboembolism Optimal Management of Anticoagulation TherapyDocument35 pagesAmerican Society of Hematology 2018 Guidelines For Management of Venous Thromboembolism Optimal Management of Anticoagulation TherapyBladimir CentenoNo ratings yet

- Procedure Sick Bay 2017Document6 pagesProcedure Sick Bay 2017Syed FareedNo ratings yet

- Botanic Drugs 1917 PDFDocument408 pagesBotanic Drugs 1917 PDFUkefácil Ukelele FacilónNo ratings yet

- Health Belief ModelDocument3 pagesHealth Belief ModelPrem Deep100% (1)

- Massage in The Ear or AuriculoterapyDocument4 pagesMassage in The Ear or Auriculoterapytelemasajes100% (3)

- Comer Emergency Department (ED) Clinical Guidelines: Diabetic Ketoacidosis (DKA) - Moderately Severe To SevereDocument6 pagesComer Emergency Department (ED) Clinical Guidelines: Diabetic Ketoacidosis (DKA) - Moderately Severe To SevereChristelle Malaluan CalumpitNo ratings yet

- CNS Case PresentationDocument9 pagesCNS Case Presentation073-NAGULAN SHIVAKUMARNo ratings yet

- PIS DR SamiDocument1 pagePIS DR SamiSami HassanNo ratings yet

- ConvoDocument44 pagesConvoLun Ding0% (1)

- Food Preservation - Pasteurization 13.02.17Document13 pagesFood Preservation - Pasteurization 13.02.17Shania Moesha AlexanderNo ratings yet

- Jugal Kishore's CardrepertoryDocument26 pagesJugal Kishore's Cardrepertorydipgang7174No ratings yet

- Suspension ExamplesDocument3 pagesSuspension ExamplesOula HatahetNo ratings yet

- Botox Issues ReferenceList Pacesetter April 2020Document16 pagesBotox Issues ReferenceList Pacesetter April 2020Amr Mohamed GalalNo ratings yet

- Docking Dan Modifikasi Struktur Senyawa Baru Turunan ParasetamolDocument5 pagesDocking Dan Modifikasi Struktur Senyawa Baru Turunan ParasetamolRiki AfriyadiNo ratings yet

- SOP 5 Template Standard Operating Procedure For Prescribing A Controlled Drug and The CollectioDocument5 pagesSOP 5 Template Standard Operating Procedure For Prescribing A Controlled Drug and The CollectioMarianne HilarioNo ratings yet

- KHS Investigation Report 07 24 12Document10 pagesKHS Investigation Report 07 24 12sunnews820No ratings yet

- Mercury Drugs Vs Judge de LeonDocument2 pagesMercury Drugs Vs Judge de LeonSherwinBriesNo ratings yet

- Manajemen Terpadu Dislipidemia PDFDocument25 pagesManajemen Terpadu Dislipidemia PDFregina fristasariNo ratings yet

- Bessette, Absolon, and Coralie M. Rousseau. Scoliosis: Causes, Symptoms and Treatment, Nova Science PublishersDocument183 pagesBessette, Absolon, and Coralie M. Rousseau. Scoliosis: Causes, Symptoms and Treatment, Nova Science PublishersDaniel MitevNo ratings yet

- Answer 2Document21 pagesAnswer 2bakesami100% (1)

- Medical EthicsDocument3 pagesMedical EthicsJona MagudsNo ratings yet

- Pidato Bahasa InggrisDocument12 pagesPidato Bahasa InggrisAlltopAmriya100% (1)