Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Tpss 435: Chapter 6: Cation Exchange Reactions

Uploaded by

kukukrunchOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Tpss 435: Chapter 6: Cation Exchange Reactions

Uploaded by

kukukrunchCopyright:

Available Formats

1

Chapter 6: Cation Exchange Reactions

I. Diffuse Double Layer

A. Boundary between charged colloid and solution ions.

Since clay particles have charge, usually negative charge, either through

isomorphic substitution or pH-induced dissociation of functional groups of organic

matter or hydrous oxides, counter ions (for negatively charged surface counter ions

are cations, or positive ions) are attracted by the charged surface and accumulated

close to the charged surface. This phenomenon has the same principle as an electric

plate condenser (or capacitor). Thats why it is given the name electric double layer,

or double layer, for short.

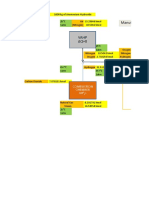

According to this diagram of the double layer, a clear cut boundary is established,

and if you draw conc. of the counter ions as a function of distance from the charged

surface, you would get a graph like this (B). Concentration is high and constant

with respect to the distance where x < x

1

, then x > x

1,

for example, concentration

suddenly drops to near zero. This condition happens in electric plate condensors

T

P

S

S

4

3

5

2

but does not really happen in the soil double layer. In soils, the boundary between 2

layers is not clear-cut. The actual distribution of cations in the liquid phase changes

gradually from a high concentration near the charged surface to a considerably

lower concentration in the bulk solution. If you draw a diagram of concentration as

a function of distance from the charged surface, it looks like this (D). Such a

distribution is referred to as the diffuse double layer.

When people are talking about the diffuse double layer, you often hear the terms:

Helmholtz layer and stern model.

B. Helmholtz double layer.

A proposed model for the distribution of cations in solution such that a layer of

cations balancing the negative charge of colloid is located immediately adjacent to

the colloid surface. This model is not very realistic for soils but is easy to handle

mathematically.

C. Stern model

Stern model is a modification of the diffuse double layer in which some of the

cations are regarded as strongly sorbed to specific colloid exchange sites. The

remaining cations form a diffuse double layer around the particles of reduced

charge density.

T

P

S

S

4

3

5

3

D. Thickness of the double layer

It is sometimes convenient to think of the thickness of the double layer,

although the layer is so diffuse that this distance cannot be defined precisely.

In this figure, d is the thickness of the diffuse double layer. As you can see, these

thicknesses are very small (less than 10 nm) as compared to the dimension of soil

pore (1-5 m) . If you notice, you see that thickness of the double layer

1.) decreases with increasing electrolyte concentration

2.) decreases with increasing ion valence.

The cations within the double layer that neutralize the negative charge of colloid

surface are called exchangeable cations.

II. Properties of cation exchange reactions

A. Reversibility of cation exchange reactions

In general, cation exchange reactions are reversible unless some special reactions

also occur. These special reactions (exceptions) are:

T

P

S

S

4

3

5

4

1.) Preferential bonding by organic matter to trace metals.

For example, Cu can be held so tightly by O.M. through covalent bonds that it

disappears from the soil solution.

2.) Cation fixation

e.g. K

+

or NH

4

+

is fixed by vermiculite.

3.) Steric hindrance

Organic ions/molecules, e.g., some pesticide molecules that are physically too

big to approach exchange sites.

B. Stoichiometry

Stoichiometry means the exchange of one equivalent of a cation for one

equivalent of another cation.

Mg

2+

+ Soil-K

2

= 2K

+

+ Soil-Mg

Here 1 mole (or 2 equivalents) of Mg

2+

is replacing 2 moles or 2 equivalents of

K

+

in the exchange sites.

C. Reaction rate

Exchange reactions are very rapid. They themselves occur instantaneously. The

rate limiting step is often the diffusion step of ions to and from the colloid surface.

This diffusion step may take several minutes or hours. This situation is especially

true for soils with low water content such as under field water conditions.

(unsaturated condition)

D. Mass action principle

1.) Replacement by high concentration

Since cation exchange reactions are reversible, they can be driven forward or

backward by manipulating the relative concentration of reactants and products.

Ex: Ca-X + 2Na

+

(high conc.) (Na)

2

X + Ca

2+

(low conc.)

K = (Ca

2+

) (Na

2

--

X) = (Ca

2+

) * (Na

2

X)

(Na

+

)

2

(Ca--X) (Na

+

)

2

(Ca--X)

T

P

S

S

4

3

5

5

2.) Replacement by forming precipitates

Ca -X+ Na

2

CO

3

(Na)

2

-

X + CaCO

3

(precipitate)

This reaction will be driven completely to the right because CaCO3 as a product

is precipitated out of solution.

3.) Replacement by forming volatile gas

NH

4

-X+ NaOH Na-X+ NH

4

OH Na -X+ H

2

O + NH

3

(g)

NH

3

is lost as a gas, therefore the reaction is shifted completely to the right

and all exchangeable NH

4

+

are replaced by Na

+

.

E. Valence Dilution

Dilution of the equilibrium solution favors the retention of higher valent cations.

Ex: Ca

-

X+ 2NH

4

+

(NH

4

)

2

-

X+ Ca

2+

K = (NH

4

)

2

-

X

*

Ca

2+

(NH

4

)

2

-

X = K *

(NH

4

+

)

2

Ca-X (NH

4

+

)

2

Ca- X Ca

2+

Ex: 1

st

. situation: NH

4

+

= 1 mM, Ca

2+

= 1 mM (NH

4

)

2

-

X = K *

1 = K

Ca- X 1

2

nd

. situation: NH

4

+

= 0.1 mM, Ca

2+

= 0.1 mM (NH

4

)

2

-

X = K *

.01 = 0.1 K

Ca- X 0.1

The ratio of exch. NH

4

to exch. Ca reduces by 10 times, that is, more Ca

2+

will

stay in exchange sites relative to NH

4

+

upon dilution.

F. Complimentary cations (relative replacing power)

Exchange one cation for another in the presence of a third (or complimentary)

cation becomes easier as the retention strength of the third cation increases.

Ex: Al

3+

and On exchangeables, add K

+

Ca

2+

K

+

will replace more Ca

2+

than if Al

3+

werent there.

Or, there are 2 soil systems. In one we have..

T

P

S

S

4

3

5

6

Al

3+

and in the other we have Na

+

Ca

2+

Ca

2+

on exch. site on exch. site

When we add NH

4

+

as the replacing cation to both systems, NH

4

+

will replace

more Ca

2+

in the Al/Ca system than in the Na/Ca system. The reason for this is that

Al

3+

has a much stronger retention strength than Na

+

, therefore, NH

4

can replace

much less Al than it can with Na. Consequently more NH

4

+

remains in solution to

replace Ca

2+

in the Ca-Al soil.

G. Anion effects

The anion associated with an exchanging cation can affect cation exchange

reaction by driving the reaction toward completion if the end products are:

1.) Weakly dissociated

Ex: liming reaction

2 H-X + Ca(OH)

2

Ca-X+ 2H

2

O

Since H

2

O is a weakly dissociated molecule, this reaction will go completely

to the right.

2.) Less soluble

Al-X + 3/2 Ca(OH)

2

Al(OH)

3

+ 2/3 Ca-X

3.) More volatile

Another liming reaction with CaCO3 as liming material.

2 H-X + CaCO

3

Ca-X + H

2

CO

3

Ca-X + H

2

O + CO

2

H. Colloid- specific effects

Soil colloids with high surface-charge density favor the retention of polyvalent

cations.

EX: Vermiculite with higher surface-charge density than montmorillonite will

retain more Ca

2+

with respect to Na+ as compared to montmorillonite.

T

P

S

S

4

3

5

7

III. Cation Exchange Selectivity

1. Coulomb law:

The attraction of cations for negatively charged surfaces can be qualitatively

expressed by Coulomb law:

F = K * [q

1

q

2

] / d

2

where K is a proportionality constant, q1 and q2 are the charges of the two ions, and

d is the distance between the two ions.

What this formula says is that the attraction force is proportional to the magnitude

of charge and inversely proportional to the square of the distance. However, this

formula does not predict the selectivity or preference of one cation over another of

the same valence. Such preference can only be explained with cation size.

we need to distinguish between 2 types of cation sizes:

a. crystal radius

Is the radius of the ion before water association or hydration

b. hydrated radius

Is the radius of the ion including its associated water molecules.

Usually the 2 types of radus are inversely proportional to each other for ions

with the same valence. For example, an ion with smaller crystal radius has higher

charge density per unit volume, therefore this ion will attract more water and its

hydrated radius is much larger than that of an ion B with larger crystal radius.

Ions with smaller hydrated radus can get closer to colloid surface and their

coulombic attraction by the surface is much stronger, consequently the ions are

retained more tightly by the surface.

2.) Order of Replaceability

Within a given valence series, the degree of replaceability of an ion decreases as

its hydrated radius decreases. This statement means that it is harder to replace a

cation with a smaller hydrated radius, than one with a larger hydrated radius, and

the relative replaceability of cations is called lyotropic series.

T

P

S

S

4

3

5

8

Ex : Li ~ Na > K ~ NH

4

> Rb > Cs

easy to replace hard to replace

The most important factor in determining the order of replaceability of a given

ion is its valence. Divalent ions in general are retained more strongly than

monovalent ions, trivalent ions are retained even more strongly.

Ex: K

+

> Ca

2+

> Al

3+

easy to replace -- hard to replace

3. Selectivity beyond Coulombic forces.

In addition to electrostatic attraction, some colloids have high preference for

specific cations, e.g., Mg in vermiculite. The hydrated Mg ion apparently fits so

well into the water network between parallel sheets of vermiculite that Mg

2+

is

preferred over Ca

2+

in a wide range of concentrations.

Another example of abnormally high preference for a particular ion is the

retention of K

+

and NH

4

+

by vermiculite and weather mica. Apparently these ions

have low hydration energy, therefore they are easily dehydrated, become smaller,

and are retained strongly by mica and vermiculite.

IV. Cation Exchange Equations

Several exchange equations have been proposed, each has its own advantage and

disadvantage, and the choice of a particular equation is often based on your

familiarity with that equation.

1.) Kerr equation or mass-action equation.

Ca-X + 2Na

+

2Na-X + Ca

2+

The reactions coefficient is....

K

k

= (Na-X)

2

(Ca

2+

) (1)

(Ca-X) (Na

+

)

2

T

P

S

S

4

3

5

9

Here Na-X and Ca-X are exchangeable cations. Ca and Na are ions is solution.

All the terms here are in activity units, even though Kerr originally used

concentrations in place of activities. And K

k

remains fairly constant only over a

narrow range of concentration. Since activities of exchangeable cations cannot be

measured or calculated precisely, the above equation is often written as:

(in mmole/g) (Na-X)

2

= K

k

* (Na

+

)

2

(2)

(Ca-X) (Ca

2+

)

The activities of ions in solution can be estimated from Debye-Huckel theory or by

specific-ion-electrode measurement. K

k

is taken by averaging several values.

Knowing K

k

and the ratio of (Na)

2

/(Ca

2+

), the ratio of exchangeable (Na-X)

2

/(Ca-X)

can be estimated. Consequently, the relative change of one exchangeable ion over

another can be predicted as the soil solution composition changes.

2.) Vanselow equation

As I mentioned above, K

k

is not constant but varies considerably, especially over

a wide range of exchangeable cation compositions. Vanselow in 1932 propposed

that if activity of an adsorbed cation on clay was expressed as the mole fraction of

that cation, then the variation of K

k

would be reduced.

Ex: Activity of [Na-X] = [Na-X] .

[Na-X] + [Ca-X]

Here, all the units are in mmole/g

Act. [Ca-X] = [Ca-X] .

[Na-X] + [Ca-X]

substituting these values into eq. 2 gives:

[Na-X]

2

. = K

v

(Na

+

)

2

(3)

[Ca-X][Na-X + Ca-X] (Ca

2+

)

For homovalent exchange, the 2 equations are the same; for heterovalent exchange,

the Vanselow equation differs from the Kerr equation by the factor of [Na-X + Ca-

X].

T

P

S

S

4

3

5

10

3.) Gapon equation

The most commonly used equation is the Gapon equation which has a square root

term:

(Ca)

1/2

X + Na

+

Na-X + Ca

2+

and [Na-X] = K

G

[Na

+

] (4)

[Ca

1/2

X] [Ca

2+

]

1/2

Where [NaX] and [Ca

1/2

X] are exchangeable cation concentrations and in meq/g,

(or mmol of charge/g) and [Na

+

], [Ca

2+

] are solution cation concentrations in

mmole/liter.

4. An example of using exchange equations.

Can we predict what happens to a heavy metal when a small amount of it is added

to soil?

Ex: To 100g soil we add 1micromole of Cd

2+

and this soil initially has 5 mmoles

of exchangeable Ca

2+

.

Ca-X + Cd

2+

Cd-X + Ca

2+

K = (Ca

2+

) * [Cd-X]

(Cd

2+

) [Ca-X]

let y = amount of adsorbed Cd

2+

(in mmole/100g) at equilibrium.

[CaX] = 5-y

[CdX] = y

(Ca 2+) = y

(Cd 2+) = 0.001- y

Lets assume that the affinity for Ca and Cd of this soil is similar, that is K =1.

Then

1 = y * y = y

2

.

0.001-y 5-y (0.001-y) (5-y)

T

P

S

S

4

3

5

11

or: y

2

= (0.001-y) (5-y)

y

2

= 0.005- 5y 0.001y + y

2

5.001* y = 0.005

y = 0.005 / 5.001 = 0.0009998 mmole = 0.9998 micromoles

This means that : 99.98% of Cd

2+

will be adsorbed.

T

P

S

S

4

3

5

You might also like

- Progress in the Science and Technology of the Rare Earths: Volume 2From EverandProgress in the Science and Technology of the Rare Earths: Volume 2No ratings yet

- Physical & Chemical Properties (Cont'D.)Document36 pagesPhysical & Chemical Properties (Cont'D.)Nagwa MansyNo ratings yet

- Ion Exchange: Soil ColloidsDocument6 pagesIon Exchange: Soil ColloidsAbdullah Mamun100% (1)

- T. J. Greytak Et Al - Bose-Einstein Condensation in Atomic HydrogenDocument9 pagesT. J. Greytak Et Al - Bose-Einstein Condensation in Atomic HydrogenJuaxmawNo ratings yet

- Part Vi Stabilization, Kinetics&thermodyamics of ComplexesDocument32 pagesPart Vi Stabilization, Kinetics&thermodyamics of ComplexesJohn QambeshNo ratings yet

- 3 Electrochemistry 33Document33 pages3 Electrochemistry 33Aryan POONIANo ratings yet

- A2 Level: Storyline: Answers To AssignmentsDocument6 pagesA2 Level: Storyline: Answers To Assignmentsabbasn_9No ratings yet

- Ck&e 1Document33 pagesCk&e 1Zekarias LibenaNo ratings yet

- Electron Transfer Redox ReactionsDocument33 pagesElectron Transfer Redox ReactionsAlifiya DholkawalaNo ratings yet

- 5th IJSO-Test Solution PDFDocument7 pages5th IJSO-Test Solution PDFВук РадовићNo ratings yet

- Answers To Assignment2-2009Document6 pagesAnswers To Assignment2-2009ElmIeyHakiemiEyNo ratings yet

- XI 04 Chemical BondingDocument65 pagesXI 04 Chemical Bondingkaushik247100% (1)

- Electrochemistry - NotesDocument4 pagesElectrochemistry - Notesn611704No ratings yet

- Lecture 4: Adsorption: The Islamic University of Gaza-Environmental Engineering Department Water Treatment (EENV - 4331)Document45 pagesLecture 4: Adsorption: The Islamic University of Gaza-Environmental Engineering Department Water Treatment (EENV - 4331)Anuja Padole100% (1)

- Mass EquationsDocument2 pagesMass EquationsjiyaNo ratings yet

- Transition Metal 4Document4 pagesTransition Metal 4Sushant ShahNo ratings yet

- 11.metamorphic ReactionsDocument16 pages11.metamorphic ReactionsAsmita BhattacharyaNo ratings yet

- Electrochemistry 2Document42 pagesElectrochemistry 2Sara FatimaNo ratings yet

- Chem Quiz 8Document10 pagesChem Quiz 8Gaurav ShekharNo ratings yet

- CBSE Class 12 Chemistry Sample Paper Solution Set 5Document13 pagesCBSE Class 12 Chemistry Sample Paper Solution Set 5Ayush KumarNo ratings yet

- 4 Ion ExchangeDocument19 pages4 Ion ExchangeAl Malik Delmo MamintalNo ratings yet

- CBSE Class 12 Chemistry Paper Sample Paper Solution Set 4Document14 pagesCBSE Class 12 Chemistry Paper Sample Paper Solution Set 4Gamer ChannelNo ratings yet

- 5.3 Notes Redox EquilibriaDocument21 pages5.3 Notes Redox EquilibriaDiego Istheillest HinesNo ratings yet

- Electronic Layers in Copper Oxide SuperconductorsDocument1 pageElectronic Layers in Copper Oxide SuperconductorsSJNo ratings yet

- Co Ordination 1Document33 pagesCo Ordination 1Nivi RajNo ratings yet

- Model Paper 6 SchemeDocument11 pagesModel Paper 6 SchemeKalyan ReddyNo ratings yet

- Metallic Character: Transition-ElementsDocument10 pagesMetallic Character: Transition-ElementsRadamael MaembongNo ratings yet

- 5 (2) Veto of Life He Our Pitch orDocument27 pages5 (2) Veto of Life He Our Pitch orStephenNo ratings yet

- Chem Rev VOL 1 073 - 90Document18 pagesChem Rev VOL 1 073 - 90Anonymous FigYuONxuuNo ratings yet

- Colour Due To Charge Transfer)Document3 pagesColour Due To Charge Transfer)aamer_shahbaaz50% (2)

- Ch-3 Sc-1 Kitabcd MSBSHSE Class 10 SolutionsDocument15 pagesCh-3 Sc-1 Kitabcd MSBSHSE Class 10 Solutionsankushsune1999No ratings yet

- Corrosion Basics PDFDocument19 pagesCorrosion Basics PDFAdityaRamaNo ratings yet

- 2020-Board Paper SolutionDocument15 pages2020-Board Paper SolutionSaugata HalderNo ratings yet

- Lattice Enthalpy, Ionisation Energy, Born-Haber Cycles, Hydration EnthalpyDocument8 pagesLattice Enthalpy, Ionisation Energy, Born-Haber Cycles, Hydration Enthalpyzubair0% (1)

- Modern Theory Principles Lecturer Saheb M. MahdiDocument34 pagesModern Theory Principles Lecturer Saheb M. MahdiAnonymous EP0GKhfNo ratings yet

- Electrochemistry: (Tuesday, 8 May 2017)Document18 pagesElectrochemistry: (Tuesday, 8 May 2017)mipa amarNo ratings yet

- Chemistry Atomic StrutureDocument36 pagesChemistry Atomic StrutureAshish NagaichNo ratings yet

- Chapter 7 Electrochemistry: ElectrolysisDocument106 pagesChapter 7 Electrochemistry: ElectrolysisNeesha RamnarineNo ratings yet

- D & F ReasoningDocument7 pagesD & F ReasoningAdithya ShibuNo ratings yet

- Chapter 8 D and F Block ElementsDocument10 pagesChapter 8 D and F Block ElementsAryan NaveenNo ratings yet

- Principles of Ion ExchangeDocument4 pagesPrinciples of Ion ExchangeGOWTHAM GUPTHANo ratings yet

- Electronic SoectraDocument25 pagesElectronic SoectraAbhinav KumarNo ratings yet

- Tid/g: P-D Hybridization Gives Rise To An Antiferromagnetic Cu2+-O-exchangeDocument1 pageTid/g: P-D Hybridization Gives Rise To An Antiferromagnetic Cu2+-O-exchangeKetanNo ratings yet

- CFTDocument15 pagesCFTGaurav BothraNo ratings yet

- ElectrochemistryDocument10 pagesElectrochemistrySsNo ratings yet

- Chemistry Cheat SheetDocument5 pagesChemistry Cheat Sheetdadadabababa100% (9)

- Summary Sa CHEMISTRYDocument12 pagesSummary Sa CHEMISTRYHazel BayanoNo ratings yet

- Chem1 Module8Document23 pagesChem1 Module8carlgavinsletartigasNo ratings yet

- Electrochemistry Notes 1 Powerpoint PDFDocument26 pagesElectrochemistry Notes 1 Powerpoint PDFMpilo ManyoniNo ratings yet

- Thermal Oxidation of SiDocument8 pagesThermal Oxidation of SiPrabal TiwariNo ratings yet

- D and F Block Elements With AnswersDocument5 pagesD and F Block Elements With AnswersFool TheNo ratings yet

- Slides15 25oc07Document36 pagesSlides15 25oc07Anuradha DanansuriyaNo ratings yet

- MLP ElectrochemistryDocument17 pagesMLP ElectrochemistrySneha GuptaNo ratings yet

- Corrosion Control and PreventionDocument34 pagesCorrosion Control and PreventionGrace Pentinio100% (1)

- MLP ElectrochemistryDocument17 pagesMLP ElectrochemistryAkash SureshNo ratings yet

- M5 Non Stoichiometri DefectDocument82 pagesM5 Non Stoichiometri DefectEric PrasetyoNo ratings yet

- 2021 - Kuliah 6 - Geokimia - KristalDocument34 pages2021 - Kuliah 6 - Geokimia - KristalKemalNo ratings yet

- Electrogravimetry: The Measurement of Amount of Charge Passed (Q) in Depositing The MetalDocument9 pagesElectrogravimetry: The Measurement of Amount of Charge Passed (Q) in Depositing The MetalnotmeNo ratings yet

- 12 Chemistry Keypoints Revision Questions Chapter 3Document22 pages12 Chemistry Keypoints Revision Questions Chapter 3Deepak PradhanNo ratings yet

- Chemical Engineering Journal: Yunfei He, Luxin Zhang, Yuting Liu, Simin Yi, Han Yu, Yujie Zhu, Ruijun SunDocument12 pagesChemical Engineering Journal: Yunfei He, Luxin Zhang, Yuting Liu, Simin Yi, Han Yu, Yujie Zhu, Ruijun Sunbruno barrosNo ratings yet

- Chapter 50 Multiple-Choice Questions - NDocument6 pagesChapter 50 Multiple-Choice Questions - NVincent haNo ratings yet

- Unit 1 General Chemistry PDFDocument29 pagesUnit 1 General Chemistry PDFchuchu maneNo ratings yet

- Chem2 Laboratory TermsManual MLS - LA1 7Document47 pagesChem2 Laboratory TermsManual MLS - LA1 7BETHEL GRACE P. MARTINEZ0% (3)

- CH1502LDocument87 pagesCH1502LDivyakumar PatelNo ratings yet

- Brochure ZytexDocument12 pagesBrochure ZytexKinjal PatelNo ratings yet

- June 2022 PaperDocument17 pagesJune 2022 PaperAthula Dias NagahawatteNo ratings yet

- Chemistry Folio Manufacture Substance in IndustryDocument23 pagesChemistry Folio Manufacture Substance in Industryseela gunalanNo ratings yet

- Nitrogeno FormasDocument22 pagesNitrogeno FormasCarlos de la TorreNo ratings yet

- Ammonium Hydroxide Material BalanceDocument3 pagesAmmonium Hydroxide Material BalanceJishnu JohnNo ratings yet

- Aqueous Lixiviantes Principle, Types, and ApplicationsDocument6 pagesAqueous Lixiviantes Principle, Types, and ApplicationsAlguien100% (1)

- Symbol and Charges For Monoatomic and Polyatomic Ions, Oxidation Number, and Acid NamesDocument3 pagesSymbol and Charges For Monoatomic and Polyatomic Ions, Oxidation Number, and Acid NamesKelvin Mark KaabayNo ratings yet

- Pharmaceutical Chemistry I (D. Pharm 1st Year)Document35 pagesPharmaceutical Chemistry I (D. Pharm 1st Year)PrathiNo ratings yet

- Analitik Kimya İzahlı TestlərDocument6 pagesAnalitik Kimya İzahlı TestlərValiNo ratings yet

- Salt Full Procedure English-Converted - 2Document6 pagesSalt Full Procedure English-Converted - 2Rekha LalNo ratings yet

- May 22 U4 QPDocument32 pagesMay 22 U4 QPolaz ayonNo ratings yet

- Chemistry - Chapter 9 (Form 5) Manufactured Substances in IndustryDocument49 pagesChemistry - Chapter 9 (Form 5) Manufactured Substances in IndustrySamyugta VijayNo ratings yet

- Ziinc SulphateDocument4 pagesZiinc SulphatePushpa KaladeviNo ratings yet

- CH 6009 FTDocument76 pagesCH 6009 FTAbdallah ShabanNo ratings yet

- Ammonium Nitrate ProductionDocument6 pagesAmmonium Nitrate ProductionAwais839No ratings yet

- Salt Analysis (Mega)Document40 pagesSalt Analysis (Mega)Anant JainNo ratings yet

- CTM 027Document10 pagesCTM 027Sayid Akhmad Bin-YahyaNo ratings yet

- Xii Chemistry Practical Salt AnalysisDocument13 pagesXii Chemistry Practical Salt AnalysisNupur GuptaNo ratings yet

- Ionic EquilibriumDocument100 pagesIonic EquilibriumShohom DeNo ratings yet

- ICSE Selina Solution For Class 9 Chemistry Chapter 2Document13 pagesICSE Selina Solution For Class 9 Chemistry Chapter 2ABHISHEK THAKURNo ratings yet

- 1995 Soluble PolymerDocument55 pages1995 Soluble PolymerDeenar Tunas RancakNo ratings yet

- Che198 Analytical Chemistry DrillsDocument18 pagesChe198 Analytical Chemistry DrillsTrebob GardayaNo ratings yet

- Nitrogen CompoundsDocument129 pagesNitrogen CompoundsSherey FathimathNo ratings yet

- Nat 5 Chem SQApp Unused 2020Document36 pagesNat 5 Chem SQApp Unused 2020muntazNo ratings yet

- 453 - Pdfsam - Timmehaus - Plant Design and Economics For Chemical EngineersDocument4 pages453 - Pdfsam - Timmehaus - Plant Design and Economics For Chemical EngineersYazan SalehNo ratings yet

- Pale Blue Dot: A Vision of the Human Future in SpaceFrom EverandPale Blue Dot: A Vision of the Human Future in SpaceRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (588)

- Sully: The Untold Story Behind the Miracle on the HudsonFrom EverandSully: The Untold Story Behind the Miracle on the HudsonRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (103)

- The Fabric of Civilization: How Textiles Made the WorldFrom EverandThe Fabric of Civilization: How Textiles Made the WorldRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (58)

- Hero Found: The Greatest POW Escape of the Vietnam WarFrom EverandHero Found: The Greatest POW Escape of the Vietnam WarRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (19)

- Challenger: A True Story of Heroism and Disaster on the Edge of SpaceFrom EverandChallenger: A True Story of Heroism and Disaster on the Edge of SpaceNo ratings yet

- The Intel Trinity: How Robert Noyce, Gordon Moore, and Andy Grove Built the World's Most Important CompanyFrom EverandThe Intel Trinity: How Robert Noyce, Gordon Moore, and Andy Grove Built the World's Most Important CompanyNo ratings yet

- The Future of Geography: How the Competition in Space Will Change Our WorldFrom EverandThe Future of Geography: How the Competition in Space Will Change Our WorldRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (6)

- The Technology Trap: Capital, Labor, and Power in the Age of AutomationFrom EverandThe Technology Trap: Capital, Labor, and Power in the Age of AutomationRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (46)

- When the Heavens Went on Sale: The Misfits and Geniuses Racing to Put Space Within ReachFrom EverandWhen the Heavens Went on Sale: The Misfits and Geniuses Racing to Put Space Within ReachRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (6)

- Permaculture for the Rest of Us: Abundant Living on Less than an AcreFrom EverandPermaculture for the Rest of Us: Abundant Living on Less than an AcreRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (33)

- From Darwin to Derrida: Selfish Genes, Social Selves, and the Meanings of LifeFrom EverandFrom Darwin to Derrida: Selfish Genes, Social Selves, and the Meanings of LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- Packing for Mars: The Curious Science of Life in the VoidFrom EverandPacking for Mars: The Curious Science of Life in the VoidRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1396)

- Transformed: Moving to the Product Operating ModelFrom EverandTransformed: Moving to the Product Operating ModelRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Fallout: The Hiroshima Cover-up and the Reporter Who Revealed It to the WorldFrom EverandFallout: The Hiroshima Cover-up and the Reporter Who Revealed It to the WorldRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (83)

- The Innovators: How a Group of Hackers, Geniuses, and Geeks Created the Digital RevolutionFrom EverandThe Innovators: How a Group of Hackers, Geniuses, and Geeks Created the Digital RevolutionRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (543)

- The Complete HVAC BIBLE for Beginners: The Most Practical & Updated Guide to Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning Systems | Installation, Troubleshooting and Repair | Residential & CommercialFrom EverandThe Complete HVAC BIBLE for Beginners: The Most Practical & Updated Guide to Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning Systems | Installation, Troubleshooting and Repair | Residential & CommercialNo ratings yet

- The End of Craving: Recovering the Lost Wisdom of Eating WellFrom EverandThe End of Craving: Recovering the Lost Wisdom of Eating WellRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (83)

- Clean Code: A Handbook of Agile Software CraftsmanshipFrom EverandClean Code: A Handbook of Agile Software CraftsmanshipRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (14)

- Dealers of Lightning: Xerox PARC and the Dawn of the Computer AgeFrom EverandDealers of Lightning: Xerox PARC and the Dawn of the Computer AgeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (88)

- The One-Straw Revolution: An Introduction to Natural FarmingFrom EverandThe One-Straw Revolution: An Introduction to Natural FarmingRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (272)

- 11 Strategies of a World-Class Cybersecurity Operations CenterFrom Everand11 Strategies of a World-Class Cybersecurity Operations CenterNo ratings yet

- Artificial Intelligence: A Guide for Thinking HumansFrom EverandArtificial Intelligence: A Guide for Thinking HumansRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (30)