Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Canine and Feline Nasal Neoplasia

Canine and Feline Nasal Neoplasia

Uploaded by

Felipe Guajardo HeitzerCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Canine and Feline Nasal Neoplasia

Canine and Feline Nasal Neoplasia

Uploaded by

Felipe Guajardo HeitzerCopyright:

Available Formats

Canine and Feline Nasal Neoplasia

Christine Malinowski, BS, DVM

Dogs and cats of our society have outgrown their status as merely pets and are now

considered our close companions and even family members. This shift in their roles has led

to pet owners seeking improved preventative medicine for their four-legged friends. Subsequently, dogs and cats are living longer lives than ever before and developing more

old-age-related diseases. One of the most devastating diseases of older animals is cancer.

Once a veterinarian has detected cancer in a pet, pet owners seek advice on their next

course of action. This article is intended to provide concise information regarding the

diagnosis and treatment of intranasal tumors of the dog and cat. This article outlines the

forms of nasal tumors that are the most common, the recommended imaging and biopsy

techniques to diagnose the tumor, and the most appropriate treatments of them.

Clin Tech Small Anim Pract 21:89-94 2006 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

KEYWORDS intranasal neoplasia, nasal carcinoma, nasal sarcoma, nasal lymphoma, nasal

turbinate destruction, epistaxis, rhinoscopy, rhinotomy, radiation therapy

ntranasal tumors comprise only about 1% of all neoplasms

of dogs and are even less common in cats.1 Speculation has

been made, although no proof has been offered, to suggest

that dolichocephalic, long-nosed, breeds of dogs or those

animals living in urban environments with relatively high

amounts of air pollution are more predisposed to developing

this type of cancer.1

Dogs

Nasal Carcinoma

Incidence and Clinical Signs

Carcinomas, including adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and undifferentiated carcinoma, comprise twothirds of intranasal cancer in dogs.1 The average age of patients with this form of cancer is 10 years, and a slight

predilection exists for male dogs.1 Medium- to large-breed

dogs seem to also be at a greater risk.1

The most common clinical signs secondary to intranasal

carcinoma are epistaxis, mucopurulent nasal discharge, facial

deformity, and occasionally epiphora.1,2 Potential differential

diagnoses for dogs with these clinical signs include systemic

hypertension, fungal or bacterial infections, and developmental anomalies.1 However, a strong presumptive diagnosis

of intranasal neoplasia can be formed for an older dog who

presents with a history of intermittent and progressive, unilateral epistaxis or nasal discharge.1 Certain dogs may present

Michigan State University, Department of Small Animal Clinical Sciences,

Lansing, MI.

Address reprint requests to: Dr. Christine Malinowski, Michigan State University, Department of Small Animal Clinical Sciences, 2016 Clifton

Avenue, Lansing, MI 48910. E-mail: cmmalinowski@michvet.com.

1096-2867/06/$-see front matter 2006 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1053/j.ctsap.2005.12.016

with concurrent neurologic deficits as well, which is consistent with extension of the cancer into the central nervous

system.1

Staging and Diagnosis

A definitive diagnosis of intranasal cancer requires evaluation

of a tissue biopsy. Before a biopsy procedure, a complete

work-up should be performed to rule out other forms of

systemic disease. A complete physical examination including

an ocular examination should be completed looking for evidence of retinal hemorrhage or tortuous retinal vessels. Accurate systemic blood pressure should be assessed along with

a complete blood count (CBC), serum biochemistry profile,

urinalysis, and clotting profile (PT/PTT or ACT).1

If these diagnostic tests are otherwise normal, three-view

thoracic radiographs should be completed and possibly skull

radiographs to assess the nasal cavity.1 The most beneficial of

the skull radiographs is commonly the open-mouth DV view

performed under anesthesia.1 In capturing this view, the exposure film is placed inside the mouth of the patient and

exposed in the DV plane. This view allows initial evaluation

of the nasal turbinates for extent of disease and for detection

of asymmetrical turbinate destruction.1 Other beneficial

views include the following: lateral, dorsoventral (entire

skull), ventro 15 rostral-dorsocaudal oblique, dorso 60

right-ventral left oblique, and dorso 60 left-ventral right

oblique.1,3 Thoracic radiographs are most often normal at the

time of diagnosis.1

Skull radiographs have an additional benefit in that they

offer direction as to where the most beneficial biopsy site

should be. A soft-tissue opacity superimposed over an area of

turbinate destruction in the caudal half of the nose most often

indicates nasal neoplasia.1 Nevertheless, the benefits of skull

89

90

Figure 1 (A) CT scan of a 9-year-old, neutered male Rottweiler with

a 2-month history of unilateral epistaxis. Diagnosis of a nasal transitional cell carcinoma was made based on histopathology of a biopsy sample obtained with alligator forceps. Notice the mass in the

dorsal aspect of the left side of the nasal cavity with the additional

fluid opacity in the ventral aspect. (B) The same Rottweiler with a

view of the nasal cavity at the level of the eyes. Notice that the mass

completely obstructs the passage of air on the left side. This finding

corroborated with physical examination findings.

radiographs are surpassed by computed tomography (CT).

CT is the ideal diagnostic tool to assess for the extent of

disease and the degree of bony involvement. This technology

has the capability of dorsal and sagittal reconstructions that

can show tumor/fluid-to-air interfaces that are completely

obscured in conventional radiographs.4 CT can indicate

cause of change more reliably than conventional radiographs1,3,4 (Fig. 1).

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) certainly has the po-

C. Malinowski

tential to be an important imaging modality for intranasal

cancer, as well. However, at this time, its limited availability

in veterinary medicine limits its practicality.

While the patient is still under anesthesia from its imaging

procedures, rhinoscopy can be used to visualize the tumor

before a biopsy procedure. Although tissue samples are relatively easy to obtain through most endoscopes, this method is

not a recommended sampling procedure. Samples from endoscopically introduced forceps are generally limited to the

superficial layer of tissue due to the small size of the instrument.1,2 The superficial layer of most nasal neoplasms consists of septic inflammation and does not yield a diagnostic

sample of the tumor itself.1,2 Therefore, rhinoscopy should be

utilized as a visual tool only, and a nasal biopsy should be

collected using a closed nasal biopsy technique: a closed

suction technique, a bone curette, or alligator forceps.1

With the closed suction technique, a large-bore (3 to 5

mm) plastic cannula is directed into the nasal cavity and the

tumor while the patient is under anesthesia.1 Negative pressure is applied as the cannula is redirected at multiple angles.1 Care should be taken during any biopsy procedure not

to advance the biopsy tool beyond the level of the medial

canthus of the eye to prevent entering the cribriform plate

and the brain.1,2 This precaution can be taken by premeasuring the tool from the naris to the medial canthus and placing

a mark on the instrument. Mild-to-moderate hemorrhage is a

secondary complication of this and other biopsy procedures

and should be avoided in any patient for which there are

concerns about coagulopathies or high risk for anesthesia.2

Cytological analysis can be facilitated by using a small

cylindrical brush that is introduced into the nasal cavity via

endoscope and then brushed against the lesion.2 This procedure is less invasive than the previously mentioned biopsy

techniques, but again requires an anesthetic event. Unfortunately, the brush technique also has a higher likelihood of

being nondiagnostic as compared with evaluation of a biopsy

or an impression smear from a biopsy sample.1,2,5 More specifically, brush cytology can fail to reveal malignancy versus

benign disease in specimens with low cellularity.2,5 Research

examining the reliability of brush cytology found that the

most accurate results came from cell-rich samples.5 In the

case of a low cell harvest, the procedure should be repeated

or a histological biopsy recommended.2,5 Nasal flushing and

swabbing are additional although generally unreliable cytologic techniques and should not be used as a sole means of

diagnosis.1,5

Nasal carcinomas are locally aggressive tumors, as is demonstrated by their ability to extend through the cribriform

plate into the brain.1 Any patient with central nervous system

signs should have a sample of cerebrospinal fluid collected

and evaluated. Increased protein or cellularity is suggestive of

brain involvement.1 Although these tumors are rarely metastatic, local lymph node aspiration is diagnostic in about 10%

of patients with nasal carcinoma.1

Treatment

Treatment of nasal neoplasia is focused on local control in a

critical location, being adjacent to the brain and eyes.1 Clinical signs are not usually observed and a diagnosis is not

usually made until the tumor is advanced. Although surgery

alone has been attempted, it is rarely curative.1,3 Rhinotomy

Tumors of the nasal cavity

has the additional downfall of a high level of acute and

chronic morbidity.1 Case reports reveal patient survival times

are not significantly different if surgery is performed or if no

treatment is offered.1 The mean survival time after diagnosis

of intranasal carcinoma with no further treatment is 3 to 6

months due to progression of local disease.1 Immunotherapy

and cryosurgery have also been used for a small number of

dogs but have done nothing to improve survival times.1

Radiation therapy is the most effective treatment available

at this time.1 Used either alone or in combination with rhinotomy, survival times are increased to 8 to 25 months depending on the treatment protocol followed.1 In one study of

42 dogs with intranasal tumors, the disease-free interval for

dogs treated with radiotherapy alone was shorter than for

dogs treated with surgery and radiotherapy; however, the

overall survival times of the two groups were not significantly

different.6 On retrospective analysis, the researchers of that

study concluded that radiation treatment alone caused less

patient morbidity than rhinotomy and radiation combined

despite the earlier recurrence of clinical signs.6 In a more

recent retrospective analysis, dogs that underwent surgery

followed by radiation therapy were significantly more likely

to develop rhinitis or osteomyelitis than dogs treated with

radiation therapy alone.7 Also noted in that study was that the

rate of local recurrence of neoplasia was not significantly

different between the two groups. The median survival time

for dogs in the radiotherapy-only group was significantly

shorter (68% alive after 1 year) than for the radiotherapy and

surgery group (77% alive after 1 year).7

Treatment with orthovoltage, high-energy megavoltage

and cobalt radiation have been used individually and in combination.1 Overall, adenocarcinomas respond better to radiation therapy than squamous cell carcinoma or undifferentiated carcinoma and have a relatively better long-term

prognosis.1 Unfortunately, no single protocol has been embraced by the veterinary community, which complicates appropriate comparison of survival times.1 Chemotherapeutic

agents such as cisplatin seem to be effective adjunctive treatments, improving survival times when used as a radiation

sensitizer.1

During and after the completion of radiation therapy,

acute phase side effects are often noted. Specifically, rhinitis

and mucositis can be severe and can last up to 4 to 8 weeks

after treatment.1 Keratoconjunctivitis sicca, corneal ulceration, and cataracts are common secondary ocular changes.1

91

Figure 2 (A) An example of a nasal chondrosarcoma in a 12-year-old,

neutered male American Foxhound. Notice the asymmetry of the

left side of the face, rostral to the zygomatic arch that is visible on

close observation. (B) The same American Foxhound diagnosed

with a nasal chondrosarcoma metastatic to the lungs. Notice the

soft-tissue swelling to the left of midline and at the caudal aspect of

the hard palate that is visible on oral examination. (Color version of

figure is available online.)

Nasal Sarcoma

Incidence and Clinical Signs

Sarcomas, including fibrosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, osteosarcoma, and undifferentiated sarcoma, comprise the remainder of common intranasal tumors in dogs.1 The average

age of patients with this form of cancer is again about 10

years; however, chondrosarcoma has been shown to occur

commonly in young dogs.1 Medium- to large-breed dogs

seem to be at a greater risk as well.1

The most common clinical signs occurring secondary to

intranasal sarcoma are epistaxis, mucopurulent nasal discharge, facial deformity, and occasionally epiphora1 (Fig. 2A

and B). The differential diagnoses for intranasal neoplasia

were listed in the Incidence and Clinical Signs of nasal

carcinoma.1 As before, a strong presumptive diagnosis for

intranasal neoplasia can be formed for an older dog who

presents with a history of intermittent and progressive, unilateral epistaxis or nasal discharge.1 Concurrent neurologic

deficits are consistent with extension of the neoplasia into the

central nervous system.1

Staging and Diagnosis

A complete physical examination including an ocular examination should be completed. Accurate systemic blood pressure should be assessed along with complete blood work,

urinalysis, and a clotting profile.1 If these diagnostic tests do

not suggest underlying metabolic disease, three-view tho-

C. Malinowski

92

racic radiographs and imaging of the nasal tumor should be

completed.1 As with nasal carcinomas, thoracic radiographs

are often within normal limits at the time of diagnosis.1 CT is

the ideal diagnostic tool available to assess for the extent of

disease and the degree of bony involvement, but skull radiographs can be very beneficial in directing a biopsy procedure.1

A definitive diagnosis of intranasal cancer requires evaluation of a tissue biopsy. Rhinoscopy and endoscopic biopsy

instruments are limited in their function as it relates to nasal

sarcomas as well as nasal carcinomas. A nasal biopsy should

be collected using a closed nasal biopsy technique.1 Mild-tomoderate hemorrhage should be expected; therefore, a biopsy procedure should be avoided in any patient for which

there are concerns about coagulopathies or high risk for anesthesia.2 Special attention should be given during any biopsy procedure not to advance the biopsy tool beyond the

level of the medial canthus of the eye to prevent entering the

cribriform plate and the brain.1,2

Local lymph node aspiration has had a limited amount of

success in detecting nasal sarcomas as these tumors are rarely

metastatic.1 Fluid analysis, nasal washing, and brush cytology have a high likelihood of being nondiagnostic when mesenchymal tumors are present as compared with evaluation of

a biopsy.1,2 These methods can fail to reveal malignancy versus benign disease.2

Treatment

Treatment of nasal sarcomas is focused on local control.1 As is

the case with nasal carcinoma, patient survival times are not

significantly different if surgery is performed or if no treatment is offered. Bone invasion occurs early, and although

surgery alone has been attempted, it is rarely curative and has

a high level of acute and chronic morbidity.1 The mean survival time is 3 to 6 months due to progression of local disease.1

Radiation therapy is the most effective treatment available

at this time.1,6 Used either alone or in combination with rhinotomy, survival times are increased to between 8 and 25

months depending on the treatment protocol followed.1,6

Nasal sarcoma has been treated with orthovoltage, high-energy megavoltage, and Cobalt radiation alone and in combination as was discussed for nasal carcinoma.1,6 During and

after the completion of these protocols, acute phase side effects of radiation on the mucosal surfaces and eyes were often

noted.1,6

Even if dogs have a resolution of clinical signs, few dogs are

considered cured if followed to necropsy.1 Despite the relatively nonmetastatic nature of nasal sarcoma in untreated

animals, metastatic lesions were found beyond the local site

in 40% of 285 cases given radiation therapy and followed to

necropsy.1 Most metastatic lesions were found in the lymph

node or lungs of those dogs and believed to be due to their

prolonged survival times.1 As more improvements in longterm survival are achieved, the true metastatic potential of

nasal neoplasia may be revealed.1 Chemotherapeutic agents,

especially platinum agents, seem to be effective adjunctive

treatments improving survival times when used as radiation

sensitizers.1

Overall, nasal sarcomas have a better long-term prognosis

than carcinomas, with chondrosarcomas responding the best

to treatment.1,6

Cats

Nasopharyngeal Polyps

Incidence and Clinical Signs

Nasopharyngeal polyps typically occur in cats less than 2

years of age. In one study, greater than 80% of affected cats

were less than 1 year of age.2 The most common clinical signs

were sneezing, snuffling, and upper airway stridor.1,2 Less

commonly, aural or nasal discharge was noted. This disease

of cats is less likely to be of neoplastic origin and more likely

of primary or secondary inflammatory origin.1 The polyps

generally arise from the mucosa of the tympanic bullae or

eustachian tube. The pedunculated mass then extends into

the oral cavity or external ear canal.1 Additional clinical signs

to note include head tilt, circling, and possible nystagmus.2

Staging and Diagnosis

Staging includes a minimum database of a CBC, serum biochemistry profile, urinalysis, FeLV/FIV serology, T4 testing,

and three-view thoracic radiographs. In addition, skull radiographs can assess for soft-tissue opacities within the tympanic bullae, indicating fluid or mass extension into the area.1

Open-mouth radiographs to assess each of the bullae are

recommended, but can give equivocal information. CT scan

of the skull would reveal the full extent of the mass.2

Treatment

Involvement of the bulla is an indication for treatment.2 In

that situation, bulla osteotomy with concurrent appropriate

sampling of the contents for bacteriologic culture and sensitivity should be performed. The patient should then be

treated appropriately in coordination with the results. The

owner should be warned about the likely development of

Horners syndrome postoperatively, which is likely a transient complication that resolves within a month of surgery.2

If involvement of the bulla is not noted, removal should be

sought by excision, including as much of the pedicle as possible or by placing traction on the mass leading to rupture of

the pedicle.2 Recurrence was noted after surgical removal in

about 20% of cases according to one study and can occur

anywhere from 1 month to 3 years after surgery.2 Regrowth

can occur multiple times.

Benign Nasal Tumors

Benign tumors, such as adenomas, fibromas, fibropapillomas, hemangiomas, and chondromas, have been described in

various case reports.2 Such benign tumors, especially papillomas and fibromas, may be difficult to differentiate from an

inflammatory nasopharyngeal polyp and vice versa.2 They

most commonly cause sneezing and snuffling, but can be

associated with facial deformity as well.2 Surgical removal

with histopathology is generally curative as well as diagnostic.2

Nasal Carcinomas

Although tumors of the nasal planum, especially squamous

cell carcinoma (SCC), should be considered when evaluating

a patient with facial deformity, sneezing, or upper airway

Tumors of the nasal cavity

stridor, this article describes only tumors of intranasal origin.

Carcinomas are the most common form of intranasal neoplasm of cats second to nasal lymphoma.2

Incidence and Clinical Signs

As opposed to nasopharyngeal polyps, intranasal carcinomas generally affect cats greater than 6 years of age.2 The

most common clinical signs include sneezing, snuffling,

facial deformity, enophthalmos, exophthalmos, and

chronic epiphora.1,2,8 Unlike nasal neoplasms in the dog,

nasal discharge and epistaxis are less common signs in

cats, occurring in only about one-third of those affected.2

Seizures can be an associated sign if the neoplasm has

extended beyond the cribriform plate.2,8 Clinical signs relating to a nasal carcinoma can be present for a relatively

short period of time, 2 to 4 weeks, to years before a diagnosis is made.2

Of the carcinomas reported, about equal proportions have

been of adenocarcinoma and undifferentiated carcinoma as

well as a small number of SCC.2 As is the case for dogs,

speculation has been made for cats with longer nasal passages, such as the Oriental breeds, to have a predisposition

for developing nasal tumor malignancies.2 No definitive support for such a claim exists in the literature.

Staging and Diagnosis

The minimum database for a patient with nasal carcinoma

includes a CBC, serum biochemistry profile, urinalysis,

FeLV/FIV serology, T4 testing, and three-view thoracic radiographs.2 In addition, evaluation of local lymph nodes, nasal

radiographs, and a CT scan is recommended.2 Skull radiographs may indicate destruction of nasal turbinates with or

without a mass lesion and can direct one to an area likely to

yield the most diagnostic material from a biopsy.1,2 Rhinoscopy allows direct visualization of the gross disease present;

however, CT is necessary to accurately delineate its full extent.2

Differential diagnoses in the face of nasal turbinate erosion

include severe rhinitis and cryptococcosis as well as intranasal neoplasia. However, neoplasia can be considered more

likely with the presence of unilateral radiographic lesions,

lysis of a lateral bone, or tooth loss.2

The most accurate method of diagnosis short of rhinotomy

is a closed nasal biopsy, which also has the benefit of reducing contamination through the skin.2 Although biopsy during an endoscopic procedure is relatively easy in cats, unfortunately, it is inadequate for accurate diagnosis.2 As is the

situation with dogs, the limited size of the biopsy sample

through the endoscope restricts samples to the superficial

layer, which usually consists of septic inflammation.2 Therefore, a nasal biopsy should be collected using a closed suction

technique, a bone curette, or a small cup biopsy instrument

introduced through the nares.

With the closed suction technique, a large-bore (3 to 5

mm) plastic cannula is directed into the nasal cavity and the

tumor with negative pressure while the patient is under anesthesia.1 Care should be taken during the biopsy procedure

to not advance the biopsy tool beyond the level of the medial

canthus of the eye to prevent entering the cribriform plate or

the brain.1,2 Mild-to-moderate hemorrhage is a secondary

complication of this procedure and should be avoided in any

93

patient for which there are concerns about coagulopathies or

high risk for anesthesia.2

Although metastases are uncommon, fine-needle aspiration of an enlarged local lymph node can give valuable cytologic information in combination with cytology or histopathology performed on the gross mass.1,2 Brush cytology is a

fairly noninvasive procedure that can be used in cats to provide valuable information. Caution should be used when

interpreting results as is described in Staging and Diagnosis

of canine nasal carcinomas.2,5

Treatment

Cats have a poor tolerance for rhinotomy.1 Surgery alone for

nasal carcinoma has been reported in a small number of cats

and was correlated with relatively fast tumor recurrence (1 to

12 weeks).2 When surgery was combined with orthovoltage

radiation therapy in six cats with nasal carcinoma, the results

were much improved.2 No recurrence was noted in four of

the cats, two of which died 5 months after therapy of unrelated causes and two of which remained disease-free at 26

and 40 months after therapy.2 Recurrence was noted in the

other two cats 21 and 62 months after therapy.2 Treatment

with surgery and Cobalt-60 irradiation has had less success

with tumor recurrence within 1 year of treatment for each of

three cats.2

Cats treated with Cobalt-60, orthovoltage, or megavoltage

alone experienced moderate success, but all had either local

tumor regrowth or distant metastasis (local lymph node or

lungs) within 11 months of treatment.2 The acute side effects

of radiation therapy were mild overall.2 The degree of moist

desquamation and ocular effects were less than those noted

in similarly treated dogs.2 These relatively mild side effects

could be a sign that cats may be tolerant of larger doses of

radiation.2 Their higher tolerance for radiation therapy may

prove beneficial and should be examined in future reports.

Multiple chemotherapeutic agents including mitoxantrone, carboplatin, cyclophosphamide, and vincristine

have been used without surgery.2 Unfortunately, the latter

two drugs did not cause any noticeable remission.2 Carboplatin appears to be the most promising option for chemotherapeutic treatment of feline nasal carcinoma.

Finally, supportive care is an important treatment that

should not be overlooked. Affected cats will have a reduced

ability to smell and should be treated with appetite stimulants and have their food heated to entice them to eat.1 If oral

nutrition is not of an adequate amount, placement of an

enteral feeding tube should be considered if therapy is likely

to be prolonged.2 In addition, topical eye care will be necessary on a short-term and possibly long-term basis in conjunction with radiation therapy.2

Nasal Sarcomas

Limited reports of intranasal sarcomas have described intranasal fibrosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, osteosarcoma, hemangiosarcoma, and undifferentiated sarcoma.2 Two cats with

chondrosarcoma were treated with surgery alone and both

experienced regrowth of the tumor 6 months later.2 An intranasal osteosarcoma was also treated with surgery alone

twice over a 14-week period and was insufficient to control

tumor growth.2 Six cats with nasal fibrosarcoma or an undifferentiated form of sarcoma were treated with radiation therapy alone and had good results similar to cats with nasal

C. Malinowski

94

carcinoma.2 The median survival for this group was 10

months.2 As can be speculated for cats with nasal carcinoma,

cats with nasal sarcoma that are to be treated with radiation

therapy alone may be able to be treated with larger doses of

radiation than those previously used.2

Olfactory Neuroblastoma

Also referred to as sympathicoblastoma and esthesioneuroblastoma, olfactory neuroblastoma appears to be induced by

the feline leukemia virus (FeLV).2 The most common clinical

signs in addition to nasal discharge and sneezing are CNS

signs including circling, ataxia, behavior changes, and paresis.2 This tumor originates from the neuroectoderm and the

clinical signs appear to stem from the extension of the tumor

into the CNS.8 Support for the role of FeLV in the induction

of this neoplasm is in the presence of FeLV DNA in the tumor

of CNS affected cats correlated with its absence in normal

brain tissue of the same cats.2 As opposed to other intranasal

neoplasia, this tumor is highly metastatic. Initial treatment

with radiation therapy appears to be the most effective, but

early recurrence is expected.2 Follow-up treatment with chemotherapeutics, doxorubicin and carboplatin, may be effective, but is often complicated by the concurrent FeLV infection.2 Prognosis is generally poor.

Nasal Lymphoma

Incidence and Clinical Signs

Nasal lymphoma is the most common cause of nasopharyngeal disease in cats.2 The median age of affected cats among

60 case reports was 8 years old, but ranged from 2 to 19

years.2 Clinical signs vary in duration and are similar to those

reported for other forms of nasal neoplasia in cats: nasal

discharge, dyspnea, epistaxis, stertor, facial deformity, and

anorexia.2,9

Staging and Diagnosis

A minimum database including a CBC, serum biochemistry

profile, urinalysis, FeLV/FIV serology, T4 testing, and threeview thoracic radiographs should be collected along with an

abdominal ultrasound, nasal CT or MRI, and bone marrow

aspiration.1,2 Most affected cats do not have a concurrent

FeLV infection; however, those who are FeLV-positive have a

higher risk of developing systemic disease.2

Brush cytology was used in the previously mentioned reports to correctly identify nasal lymphoma in five of six cats.2

Rhinotomy or nasal biopsy, as described for feline nasal carcinoma, may still be needed to obtain an accurate diagnosis.2

Treatment

In cats without systemic involvement, radiation therapy can

be curative.2 Radiation therapy and chemotherapeutics have

been used alone and in combination to successfully treat

feline lymphoma limited to the nasal cavity.2 A study that

compared the efficacy of the two modalities alone or in combination in a group of 14 cats revealed no statistically different survival times.2 The most important prognostic factor

was not the treatment protocol that was followed, but the

patients FeLV antigenemia. Immunoblastic histologic phenotype and FeLV antigenemia were associated with poor survival rates.2 Patients with systemic disease required chemotherapy, preferably multidrug treatments, including

vincristine, cyclophasphamide, and methotrexate, to achieve

long-term survival.2

As with all feline nasal neoplasms and especially those

patients undergoing radiation therapy or chemotherapy,

supportive care is key. Maintaining adequate nutrition by

supplementing with appetite stimulants, antiemetics, or

placing a feeding tube is very important.1,2 Topical eye care

should be maintained in the acute phase of radiation therapy

to the head.2

Conclusion

Diagnosis of intranasal neoplasms in our dog and cat patients

employs relatively simple diagnostic procedures that can be

completed in a general practice. In most instances, the nature

of radiation therapy then requires referral of the patient to a

specialty facility to administer the most effective treatments.

References

1. Lana SE, Withrow SJ: Tumors of the respiratory systemnasal tumors,

in Withrow SJ, MacEwen EG (eds): Small Animal Clinical Oncology (ed

3). Philadelphia, PA, Saunders, 2001, pp 370-377

2. Moore AS, Ogilvie, GK: Tumors of the respiratory tract, in Ogilvie GK,

Moore AS (eds): Feline Oncology: A Comprehensive Guide to Compassionate Care. Trenton, NJ, Veterinary Learning Systems, 2001, pp 368384

3. Park RD, Beck ER, LeCouteur RA: Comparison of computed tomography and radiography for detecting changes induced by malignant nasal

neoplasia in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc 201(11):1720-1724, 1992

4. Codner EC, Lurus AG, Miller JB, et al: Comparison of computed tomography with radiography as a noninvasive diagnostic technique for

chronic nasal disease in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc 202(7):1106-1110,

1993

5. Caniatti M, Roccabianca P, Ghisleni G, et al: Evaluation of brush cytology in the diagnosis of chronic intranasal disease in cats. J Small Anim

Pract 39:73-77, 1998

6. Morris JS, Dunn KJ, Dobson JM, et al: Effects of radiotherapy alone and

surgery and radiotherapy on survival of dogs with nasal tumours. J Small

Anim Pract 35:567-573, 1994

7. Adams WM, Bjorling DE, McAnulty JF, et al: Outcome of accelerated

radiotherapy alone or in accelerated radiotherapy followed by exenteration of the nasal cavity in dogs with intranasal neoplasia: 53 cases (19902002). J Am Vet Med Assoc 227(6):936-941, 2005

8. Thon AP, Peaston AE, Madewell BR, et al: Irradiation of nonlymphoproliferative neoplasms of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses in 16

cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 204(1):78-83, 1994

9. Vail DM, Moore AS, Ogilvie GK, et al: Feline lymphoma (145 cases):

proliferation indices, cluster of differentiation 3 immunoreactivity, and

their association with prognosis in 90 cats. J Vet Intern Med 12:349-354,

1998

You might also like

- Chronic Suppurative Otitis Media in AdultsDocument10 pagesChronic Suppurative Otitis Media in AdultsRstadam TagalogNo ratings yet

- Masson's Trichrome ProtocolDocument4 pagesMasson's Trichrome Protocolitaimo100% (2)

- Color Atlas of Differential Diagnosis in Exfoliative and Aspiration Cytopathology 2nd EditionDocument1,035 pagesColor Atlas of Differential Diagnosis in Exfoliative and Aspiration Cytopathology 2nd Editiontalha riaz100% (2)

- SurgeryDocument47 pagesSurgerymohamed muhsinNo ratings yet

- 6 Neck DissectionDocument9 pages6 Neck DissectionAnne MarieNo ratings yet

- Adult Neck MassesDocument7 pagesAdult Neck MassesHanhan90No ratings yet

- Malignant Parotid Tumors: Introduction and AnatomyDocument1 pageMalignant Parotid Tumors: Introduction and AnatomyCeriaindriasariNo ratings yet

- I'Alji, Hamilton, 1.0s 4ngeles, Ctrlif.: Which AreDocument4 pagesI'Alji, Hamilton, 1.0s 4ngeles, Ctrlif.: Which AreAmalorNo ratings yet

- Cancer, Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma (NPC) : Statpearls (Internet) - Treasure Island (FL) : Statpearls Publishing 2020 JanDocument11 pagesCancer, Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma (NPC) : Statpearls (Internet) - Treasure Island (FL) : Statpearls Publishing 2020 JanikaNo ratings yet

- The Patient With Thyroid Nodule. Med Clin of NA. 2010Document13 pagesThe Patient With Thyroid Nodule. Med Clin of NA. 2010pruebaprueba321765No ratings yet

- Adenoid Cystic Carcinoma of Hard Palate: A Case ReportDocument5 pagesAdenoid Cystic Carcinoma of Hard Palate: A Case ReportHemant GuptaNo ratings yet

- ABC - Oral CancerDocument4 pagesABC - Oral Cancerdewishinta12No ratings yet

- EBM 2018 - Head and CancersDocument136 pagesEBM 2018 - Head and CancersChandramohan SettyNo ratings yet

- Cs Leak 0210021Document8 pagesCs Leak 0210021Joshua SitorusNo ratings yet

- Oral BiopsiesDocument5 pagesOral BiopsiesDiego Morales100% (1)

- 2009 0527 rs.1 PDFDocument5 pages2009 0527 rs.1 PDFpaolaNo ratings yet

- Skullbasesurg00008 0039Document5 pagesSkullbasesurg00008 0039Neetu ChadhaNo ratings yet

- August 2013 Ophthalmic PearlsDocument3 pagesAugust 2013 Ophthalmic PearlsEdi Saputra SNo ratings yet

- Oral Cancer: "The Forgotten Disease"Document16 pagesOral Cancer: "The Forgotten Disease"Amit KumarNo ratings yet

- Grand Rounds Index UTMB Otolaryngology Home PageDocument9 pagesGrand Rounds Index UTMB Otolaryngology Home PageandiNo ratings yet

- Head and Neck Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy Currecntstate of The ArtDocument7 pagesHead and Neck Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy Currecntstate of The ArtAndrés Faúndez TeránNo ratings yet

- Granular Cell Tumor of The Tongue A Case Report With Emphasis On Thediagnostic and Therapeutic Proceedings OCCRS 1000106Document3 pagesGranular Cell Tumor of The Tongue A Case Report With Emphasis On Thediagnostic and Therapeutic Proceedings OCCRS 1000106arypwNo ratings yet

- Sentinel Node Biopsy in Oral CancerDocument5 pagesSentinel Node Biopsy in Oral CancerMax FaxNo ratings yet

- Solitary Pulmonary Nodule (SPN (Document59 pagesSolitary Pulmonary Nodule (SPN (mahmod omerNo ratings yet

- HHS Public Access: Ultrasound in The Diagnosis & Management of Pleural EffusionsDocument15 pagesHHS Public Access: Ultrasound in The Diagnosis & Management of Pleural EffusionsMerlintaNo ratings yet

- Sdarticle 009 175022Document6 pagesSdarticle 009 175022hokiruNo ratings yet

- Bonnie Vorasubin, MD Arthur Wu, MD Chi Lai, MD Elliot Abemayor, MD, PHDDocument1 pageBonnie Vorasubin, MD Arthur Wu, MD Chi Lai, MD Elliot Abemayor, MD, PHDmandible removerNo ratings yet

- HEAD and NECK Case1: Monica Kristine D. ReyesDocument19 pagesHEAD and NECK Case1: Monica Kristine D. ReyesIda WulanNo ratings yet

- The Thyroid Nodule: Clinical PracticeDocument8 pagesThe Thyroid Nodule: Clinical PracticeAkhdan AufaNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis of Dental Disease IIIDocument43 pagesDiagnosis of Dental Disease IIIAmarAldujailiNo ratings yet

- RetinoblastomaDocument72 pagesRetinoblastomaDr-Muhammad IsrarNo ratings yet

- Common Anorectal Conditions:: Part I. Symptoms and ComplaintsDocument8 pagesCommon Anorectal Conditions:: Part I. Symptoms and ComplaintsSi vis pacem...No ratings yet

- LA ThoracosDocument7 pagesLA ThoracosdrradharajagopalanNo ratings yet

- Reti No Blast OmaDocument54 pagesReti No Blast OmaSaviana Tieku100% (1)

- HIPOFISISDocument4 pagesHIPOFISISisela castroNo ratings yet

- Mucosal LesionDocument16 pagesMucosal LesionMita PrasetyoNo ratings yet

- Velscope Oral PremalignancyDocument5 pagesVelscope Oral PremalignancySusanaSanoNo ratings yet

- Procedures in Primary Care DermatologyDocument5 pagesProcedures in Primary Care Dermatologyegy_tssibaNo ratings yet

- Delayed Management of Squamous Cell Carcinoma of Soft Palate: Case Report and Review of LiteratureDocument11 pagesDelayed Management of Squamous Cell Carcinoma of Soft Palate: Case Report and Review of LiteratureIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Amedee 2001Document7 pagesAmedee 2001Hakim naufaldiNo ratings yet

- Thyroidcancer: Ultrasound Imaging and Fine-Needle Aspiration BiopsyDocument21 pagesThyroidcancer: Ultrasound Imaging and Fine-Needle Aspiration BiopsyPedro Gómez RNo ratings yet

- Elliot y Meyer..2009, Radiation Therapy For Tumors of The Nasal Cavity and Paranasal SinusesDocument4 pagesElliot y Meyer..2009, Radiation Therapy For Tumors of The Nasal Cavity and Paranasal SinusesJoa FloresNo ratings yet

- Squamous Cell Carcinoma of The Conjunctiva - PMCDocument5 pagesSquamous Cell Carcinoma of The Conjunctiva - PMCGung NandaNo ratings yet

- Clinical Practice Guidelines: Penile Cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines For Diagnosis, Treatment and Follow-UpDocument10 pagesClinical Practice Guidelines: Penile Cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines For Diagnosis, Treatment and Follow-Uphypebeast dopeNo ratings yet

- Cancer of The External Auditory CanalDocument8 pagesCancer of The External Auditory Canalarief ardaNo ratings yet

- Reti No Blast OmaDocument55 pagesReti No Blast OmaIndranil GhoshNo ratings yet

- Nasopalatine Duct CystDocument4 pagesNasopalatine Duct CystVikneswaran Vîçký100% (1)

- Vestibular Schwannomas Diagnosis and Surgical TreaDocument10 pagesVestibular Schwannomas Diagnosis and Surgical TreaTimothy CaldwellNo ratings yet

- Nasogpangeal AdenoidDocument6 pagesNasogpangeal AdenoidSanggiani Diah AuliaNo ratings yet

- Palasz Adamski Gorska-Chrzastek Starzynska Studniarek Contemporary Diagnostic Imaging of Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma 2017Document10 pagesPalasz Adamski Gorska-Chrzastek Starzynska Studniarek Contemporary Diagnostic Imaging of Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma 2017Vilaseca224466No ratings yet

- ESMOGuidelines Ann Oncol 2014Document10 pagesESMOGuidelines Ann Oncol 2014Vlad CiobanuNo ratings yet

- El Nódulo TiroideoDocument8 pagesEl Nódulo Tiroideoemily peceroNo ratings yet

- Colon Adenocarcinoma With Metastasis To The GingivaDocument3 pagesColon Adenocarcinoma With Metastasis To The GingivaSafira T LNo ratings yet

- Surgical Management of Malignant TumorsDocument129 pagesSurgical Management of Malignant TumorsAshish JainNo ratings yet

- Chapter 455 Retinoblastoma Retinoblastoma Charles B. Pratt: PathologyDocument4 pagesChapter 455 Retinoblastoma Retinoblastoma Charles B. Pratt: PathologyEbook Kedokteran Bahan KuliahNo ratings yet

- Oral Cancer MADE EASYDocument19 pagesOral Cancer MADE EASYMohammedNo ratings yet

- The Evaluation and Management of Neck Masses of Unknown EtiologyDocument38 pagesThe Evaluation and Management of Neck Masses of Unknown EtiologyShaxawan Mahmood AliNo ratings yet

- Alveolar Soft Part Sarcoma of The Tongue in A 3-Year-Old Boy: A Case ReportDocument4 pagesAlveolar Soft Part Sarcoma of The Tongue in A 3-Year-Old Boy: A Case ReportMatias Ignacio Jaque IbañezNo ratings yet

- Ingrams 1997Document6 pagesIngrams 1997Mindaugas TNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Pediatric OtorhinolaryngologyDocument22 pagesInternational Journal of Pediatric OtorhinolaryngologyDear Farah SielmaNo ratings yet

- Case Studies in Advanced Skin Cancer Management: An Osce Viva ResourceFrom EverandCase Studies in Advanced Skin Cancer Management: An Osce Viva ResourceNo ratings yet

- Cystoisosporosis in DogsDocument3 pagesCystoisosporosis in DogsFelipe Guajardo HeitzerNo ratings yet

- Hemorragia Pulmonar Inducida Por El Ejercicio en El Caballo: Una RevisiónDocument12 pagesHemorragia Pulmonar Inducida Por El Ejercicio en El Caballo: Una RevisiónFelipe Guajardo HeitzerNo ratings yet

- The Zoonotic Importance of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis: Transmission From Human To MonkeyDocument2 pagesThe Zoonotic Importance of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis: Transmission From Human To MonkeyFelipe Guajardo HeitzerNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Two Methods of Endotracheal Tube Selection in DogsDocument7 pagesEvaluation of Two Methods of Endotracheal Tube Selection in DogsFelipe Guajardo HeitzerNo ratings yet

- Service Price List PDFDocument10 pagesService Price List PDFindraNo ratings yet

- Pewarnaan HistologiDocument16 pagesPewarnaan HistologiStnrhalizaNo ratings yet

- Acridine Orange Stain - Principle, Procedure and Result InterpretationDocument8 pagesAcridine Orange Stain - Principle, Procedure and Result Interpretationrhulk solomanNo ratings yet

- Gram Staining PDFDocument6 pagesGram Staining PDFMaria Chacón CarbajalNo ratings yet

- (Current Clinica (Current - Clinical - Strategies) - Gynecology - and - Obstetrics - 2004l Strategies) - Gynecology and Obstetrics 2004Document125 pages(Current Clinica (Current - Clinical - Strategies) - Gynecology - and - Obstetrics - 2004l Strategies) - Gynecology and Obstetrics 2004Eliza Stochita100% (1)

- Jurnal Obsos Effect of Intrauterine Copper Device On Cervical CytologyDocument20 pagesJurnal Obsos Effect of Intrauterine Copper Device On Cervical CytologySurianiNo ratings yet

- Webinar INAEQAS 27062020. Adhi K. Sugianli, DR., SPPK (K), M.Kes. How To Read The Gram Panel-1Document20 pagesWebinar INAEQAS 27062020. Adhi K. Sugianli, DR., SPPK (K), M.Kes. How To Read The Gram Panel-1Rini WidyantariNo ratings yet

- Molecular Testing of Thyroid NodulesDocument7 pagesMolecular Testing of Thyroid Nodulesayodeji78No ratings yet

- Group No.: Total Score Group Members:: E. Coli Smear Preparation. On Microscopic Examination, How Would You Expect ThisDocument2 pagesGroup No.: Total Score Group Members:: E. Coli Smear Preparation. On Microscopic Examination, How Would You Expect ThisRoan Eam TanNo ratings yet

- Importance of PathologyDocument27 pagesImportance of PathologyRiteka SinghNo ratings yet

- Lab Report 3Document5 pagesLab Report 3nurul ainNo ratings yet

- DIAGNOSTIC CYTOLOGY Notes (VetClinPath)Document4 pagesDIAGNOSTIC CYTOLOGY Notes (VetClinPath)Shirley Faye SalesNo ratings yet

- INR Price List Sep22Document60 pagesINR Price List Sep22YauNo ratings yet

- Special Stains For Histopathology LaboratoryDocument2 pagesSpecial Stains For Histopathology LaboratorySophiaAniceteNo ratings yet

- Gram StainDocument3 pagesGram StainAbduladheemNo ratings yet

- Cervical Cancer Screening ThesisDocument6 pagesCervical Cancer Screening Thesisbk1svxmr100% (3)

- Abnormal Pap Smear. K.C 2023Document71 pagesAbnormal Pap Smear. K.C 2023MLV AbayNo ratings yet

- Application of Exfoliative Cytology in Obstetrics & GynaecologyDocument20 pagesApplication of Exfoliative Cytology in Obstetrics & Gynaecologyapi-3705046100% (3)

- Lecture 2Document15 pagesLecture 2Mehran AsimNo ratings yet

- Consensus Practice Recommendation - Gynecologic and Non-Gynecologic CytopathologyDocument22 pagesConsensus Practice Recommendation - Gynecologic and Non-Gynecologic CytopathologyixNo ratings yet

- 3 Urine and Bladder WashingsDocument23 pages3 Urine and Bladder WashingsnanxtoyahNo ratings yet

- Pune CME 2011 BrochureDocument4 pagesPune CME 2011 BrochuredrpajaniNo ratings yet

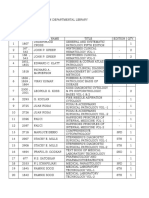

- Pathology's Books in Departmental LibraryDocument5 pagesPathology's Books in Departmental LibraryVedant RautelaNo ratings yet

- Principles of Medical Laboratory Science PracticeDocument14 pagesPrinciples of Medical Laboratory Science PracticeJanna EchavezNo ratings yet

- Gram-Staining LabDocument4 pagesGram-Staining Labapi-419388203No ratings yet

- Grams Stain-Kit: CompositionDocument3 pagesGrams Stain-Kit: Compositionhamza hamzaNo ratings yet

- The Role of Forensic PathologistDocument26 pagesThe Role of Forensic Pathologistzahari0% (1)

- Solitary Fibrous Tumor of Parotid Gland 2022Document6 pagesSolitary Fibrous Tumor of Parotid Gland 2022Reyes Ivan García CuevasNo ratings yet