Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Ishrat Hussain Article On Financial Crisis

Ishrat Hussain Article On Financial Crisis

Uploaded by

Robert DanielOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Ishrat Hussain Article On Financial Crisis

Ishrat Hussain Article On Financial Crisis

Uploaded by

Robert DanielCopyright:

Available Formats

SBP Research Bulletin

Volume 7, Number 1, 2011

Financial Sector Regulation in Pakistan: The

Way Forward

Ishrat Husain*

The 2008 global financial crisis that turned into the worst economic recession

across the world has led to some serious soul searching among the scholars and

practitioners about the ways in which financial sector has to be regulated and

supervised. There is very little doubt that the U.S. and European financial systems

were badly affected and trillions of public tax dollars had to be poured into the

system to avert a complete breakdown. The prompt and coordinated response of

the G-8 and G-20 to the crisis was something which had not been seen before.

Emerging and Developing Economies (EDEs) particularly China, India and

Pakistan however survived this onslaught as well as the 1995-96 Asian crisis. It

thus becomes an interesting question to explore as to why the financial systems in

these countries were able to insulate themselves or at least created fire walls of

safety and security that were difficult to permeate.

This paper would begin by analyzing the lessons learnt for the financial sector

from the recent global crisis, and the differentiated approach adopted to manage

and mitigate these risks. By dividing the two groups of countries Emerging &

Developing Economies (EDEs) and Developed Economies (DEs) in two broad

categories the differentiation becomes easier to follow. There are at least seven

reasons that buttress this differentiation.

First, Bank lending forms the bulk of financial sector lending in EDEs and capital

markets are not so well developed unlike the U.S. and Europe. The contagion risk

and transmission effects of an interconnected world capital markets in the EDEs

therefore remain muted and is not as intense as in the DEs.

Second, Asian countries had learnt the hard way from their 1997-98 crisis and

developed a number of shock absorbers that made them resilient in facing this

latest global crisis. Prudent macroeconomic management, credibility of policy

makers, open trading and investment regimes, accumulation of sufficient foreign

exchange reserves, an enabling environment all combined together to maintain

macroeconomic stability as well as promote growth impulses. Countries that had

Director, Institute of Business Administration and former governor, State Bank of Pakistan;

ihusain@iba.edu.pk

32

SBP Research Bulletin, Vol. 7, No. 1, 2011

attained and pursued macroeconomic and financial stability prior to the crisis

came out strongly. For example, financial sector reforms in China that created

Asset Management Companies to clean up the banks balance sheets in 2003-05

period deflected the likely shocks to the system.

Third, the banks in EDEs relied upon low cost and stable deposits for financing

their assets rather than wholesale funding that was volatile and expensive. This

permitted maturity transformation, ample liquidity to the system and preserved

confidence among investors. Unlike the U.S. and Europe where abrupt withdrawal

of wholesale funds led to a vicious cycle of distressed sale of assets, falling asset

values, shortages in capital adequacy and difficulties in raising fresh capital from

the private sources the Asian banks were not susceptible to a sudden shift in

investor sentiments.

Fourth, the central banks in EDEs had developed the capacity to draw the rules of

the game and enforce them in a way that was orderly and least disruptive. The

quality of banks portfolio had improved as a result of the central banks vigilance

and continuous watchdog functions. Mark-to market accounting, loan-loss

provisioning and capital infusion helped the strengthening of the banks.

Fifth, the banks lending in the EDEs avoided exotic products such as derivatives,

loans to hedge funds, private equity, credit default swaps, and securitization did

not figure much in their portfolios. The banks thus retained relationship with the

borrowers throughout the credit cycle and manage the risks prudently. Excessive

risk taking was thus discouraged and although it was resented at the time as too

much intrusion and micromanagement, this approach proved to be an ultimate

savior of the system.

Sixth, partial capital controls and lack of full Capital Convertibility in China,

India, Pakistan and Bangladesh did not allow large exposure to foreign currency

denominated assets. The market share of the large financial conglomerates (that

were too big to fail) was kept limited by design and therefore direct exposure of

the significantly important financial institutions to global financial markets was

quite low.

Seventh, as the markets in EDEs are generally considered imperfect, or

incomplete and the market failures loom large on the horizon the intellectual

foundation of the contemporary financial theory efficient market hypothesis

did not assume as pivotal a role as in the developed markets and therefore did not

lead to the widespread belief and practice in Market is self correcting and

therefore a hands off approach by the regulators.

Ishrat Husain

33

Ross Levine has argued that failures in the governance of financial regulations

helped cause the global financial crisis. According to him there was a fatal

inconsistency between a dynamic financial sector and a regulatory system that

failed to adapt appropriately to financial innovation. Levines main thesis is that

financial innovations, such as securitization, collateralized debt obligations and

credit default swaps, could have had primarily positive effects on the lives of most

citizens. Yet, the inability or unwillingness of the governance apparatus

overseeing financial regulation to adapt to changing conditions allowed these

financial innovations to metastasize and ruin the financial system.1

While agreeing with the broad thrust of the above argument as far as the DEs are

concerned the differentiation presented above shows that financial regulation

cannot be considered in isolation from the larger questions of market structure,

financial institutions, financial infrastructure and overall macroeconomic

framework of a country. The U.S. and European failure in regulation and

supervision cannot be ipso facto applied to Pakistan or other EDEs without

examining the context and addressing these questions. How do these factors

impinge upon regulation?

Market structure consists of the degree of competition and interlocking control

between financial institutions and business enterprises as well as the degree of

specialization within the financial sector. It is influenced by the internal

organization, management and governance structure of financial institutions.

These, in turn, are affected by the degree of government ownership and control.

A well developed technology driven financial infrastructure such as laws, payment

system, accounting and auditing can aid or hinder the efficient functioning of the

financial system. The overall macroeconomic framework particularly monetary

stability, fiscal prudence and realistic exchange rate is a powerful anchor of the

regulations. The higher is the reliance of the government on the banking system

the weaker is the effectiveness of the regulatory framework.

The regulatory framework in a particular country has therefore to be designed in

light of the prevailing market structure, the state of the financial institutions, the

condition of financial infrastructure and the overall nature of macroeconomic

policies. This framework should be broad enough to include regulations imposed

both for monetary policy as well as prudential purposes. The test of an adequate

regulatory framework is whether it can help ensure financial stability by reducing

Ross Levine (2010): The governance of financial regulation: Reform lessons from the recent

crisis, BIS Working Papers 329, November.

34

SBP Research Bulletin, Vol. 7, No. 1, 2011

the probability of bank failures and the costs of those that occur. Regulation is

primarily about changing the behavior of regulated institutions because

unconstrained market behavior tends to produce socially sub-optimal outcomes.

The regulator therefore has the responsibility to move the system towards a

socially optimum outcome.

The strategy that is followed by the State Bank of Pakistan is multi-pronged i.e. to

improve the market structure and competition, to strengthen the governance and

risk management within financial institutions, to build up an adequate financial

infrastructure and to contribute to sound macroeconomic management through

monetary and exchange rate policies. The partial or uneven success in attaining

the last goal particularly in the last three years can be ascribed to the weakness in

the fiscal policy.

The steps that have been taken to stimulate competition and improve the market

structure consist of lowering entry barriers, abolishing interest rate ceilings,

privatizing government owned banks, promoting mergers and consolidation of

financial institutions, enlarging the economies of scope for banks, liberalizing

bank branching policy and removing direct credit regulations.

In the realm of financial institutions strengthening, incentive structure is so

designed that the bank owners stand to make substantial losses in the event of

insolvency arising from excessive risk taking. Capital adequacy requirements and

loan loss provisions fulfill this role. Limiting bank holdings of excessively risky

assets, preventing lending to related parties, requiring diversification and making

sure those banks have appropriate credit appraisal, evaluation and monitoring

procedures in place are all driven by this consideration.

Corporate governance code and best practices have been prescribed for the banks

by the SBP. Adverse selection in bank entry is avoided and the individuals likely

to misuse bank do not get bank licenses. Fit and proper criteria and character

stipulations, financial back-up and past track record are scrutinized carefully for

the controlling shareholders, directors of the boards, chief executives and senior

management of the banks.

One of the positive developments in Pakistans financial infrastructure has been

the evolution of the payment system from the traditional cash and paper-based

modes of payments to a network of more sophisticated, technologically driven

systems. Although cash continues to be the dominant mode of settlement of

payments especially in rural areas, non-cash modes of payments have increased in

Ishrat Husain

35

volume over time2. The banking sector has invested heavily in IT infrastructure

in the last decade that has resulted in increased acceptance of e-banking as the

preferred retail payment instrument. As of end June 2010, the number of real-time

on-line branches constituted 73 percent of total bank branches and 31 percent of

total electronic transactions. ATM-based transactions are gaining popularity and

now account for over 50 percent of electronic transactions. These electronic

transactions constitute one third of the total transactions and have grown by 22

percent compared to paper transactions that grew at about a rate of 2 percent only.

Similarly, the implementation of the Real Time Gross Settlement (RTGS) system

by the SBP has facilitated automation of large value transactions thus reducing the

settlement risk. The legal infrastructure in Pakistan however remains weak and is

a hindrance to financial sector growth. Reforms and legal infrastructure and

enforcement are therefore necessary.

Last but not the least is the macroeconomic imbalances in fiscal and external

accounts spanning over last three years that pose system-wide challenge to

financial stability in Pakistan. Large public sector borrowing to finance budgetary

deficits as well as losses of state-owned enterprises has added to the vulnerabilities

of the banking system. The smugness of the banks who charge higher than market

prices for activities such as commodity financing have shifted to low risk

weighted assets in their portfolio by lending to the government and thus showing

higher capital adequacy ratios and larger profits could have serious repercussions

on economic growth, employment, financial inclusion and price stability in the

future. This is the sore point that has put the financial stability most at risk.

The way forward

The way forward should be paved by paying serious attention to correction of

macro-economic imbalances, particularly fiscal deficit. Unless substantial

additional tax revenues are mobilized and loss making public enterprises are

privatized the situation is likely to remain highly precarious. It is only when fiscal

position is restored to a sustainable level, future financial system would boost

investor confidence. Financial system is based on trust and can only flourish if

government ensures fiscal prudence and transparency. In this sector the collapse of

an individual institution harms not just the shareholders and employees of that

institution but a host of other innocent by-standers. This systemic risk makes the

financial sector quite unique and distinct.

The rationale behind financial deregulation that freer markets produce a superior

outcome does not work in actual practice because lending is more pro-cyclical and

State Bank of Pakistan (2010), Financial Stability Review 2009-2010 (December).

36

SBP Research Bulletin, Vol. 7, No. 1, 2011

downturns are more severe. While the need is to restrain excessive risk taking in

upturns and discourage excessive conservatism when credit to companies and

households is most needed the banks lend far too much in the upturns and far too

little in the downturns. In the boom, borrowers credit worthiness looks promising,

the value of assets goes up and lenders are willing to accept a broad range of

collaterals. Cheap availability of credit encourages leverage which further boosts

asset prices that, in turn, leads to further leverage. In the downturns, borrowers

have to cover up the short fall arising from the falling asset prices and have to

come up with more collateral. Forced sales of assets further weaken the

borrowers capacity as the realized prices are only a fraction of the face value.

Regulations on capital ratios force greater prudence in booms and cushion deleveraging during a bust.

In order to avert the systemic risk to the global financial system a clear and well

coordinated regulatory system has therefore to be put in place. The regulatory

arbitrage that so visible in case of the U.S. has to give way to a strong body that is

responsible for regulating and supervising all systemically important financial

institutions irrespective of the nature of their business or product range. The U.S.

regulatory architecture was, according to Hank Poulson, a patchwork of financial

regulatory agencies with uneven and inadequate treatment and enforcement.3

In case of Pakistan, regulatory and policy reforms in the financial sector that

began in early 1990s have made a difference which helped the country weather the

shocks of 2008 crisis. But it is equally important that we do not remain

complacent but prepare ourselves for the future challenges. This paper, building

upon the strong foundations of Pakistans regulatory framework, suggests that

there are at least nine such issues that have to be confronted and addressed in the

future. In some cases such as the first issue who is responsible for financial

stability there are no clear cut answers but in others such as extending the reach

of financial sector through diversification and financial inclusion, specific

measures are known but implementation is lagging behind. These nine critical

issues which together form the way forward are discussed in the following

paragraphs:

i)

Who is responsible for financial stability?

The global financial crisis has taught the lesson that the focus of central banks

has to expand from only monetary stability to encompass financial stability.

The challenge for the central banks, rooted deeply in past traditions and

practices that emphasized inflation and inflation targeting, is to determine how

Hank Poulson (2009), Wire News Stories.

Ishrat Husain

37

best this twining can be done without overwhelming their capacity. Whether

the central banks can have the sole responsibility for financial stability or they

should contribute towards it along with other players is an unsettled question.

What the recent experience has shown that in the event of a crisis the central

bank is the first port of call for troubled banks. As a lender of last resort,

overseer of the payment systems, provider of liquidity into the financial

markets and supervisor of individual banks the responsibility for macro

prudential oversight or financial stability ought to reside in the central bank.

But it must also be recalled that it was the fiscal authorities that took the lead

during the recent crisis by making substantial capital injections, purchasing

toxic assets, and providing guarantees of all kinds. Ultimately the lender of

last resort obligation is also discharged by the government.

Fiscal-Monetary Coordination Board provided under the SBP Act could fulfill

this responsibility but collective mechanisms such as Boards and Committees

dilute responsibility and are notorious for slow and delayed actions while the

resolution of crisis situations required timely and prompt responses. It is

therefore not obvious as to where the responsibility for financial stability can

best be located. This question needs further examination and analysis based on

empirical evidence.

ii) Risks of over-regulation

One of the natural responses to the recent crisis is to bring about new forms of

regulations and regulatory agencies to fill in the gaps and overcome the

weaknesses deficiencies in the existing system. This can, however, be taken

too far. It is true that the shadow banking system in the U.S. has to fall in line

with the banking system, systemic risk arising from too big to fail financial

institutions has to be contained and consumer protection has to be paid

attention. But a proliferation of oversight functions accompanied by new

capital and liquidity requirements may impose additional costs upon the

system. There is a danger that financial innovation may be shunned and the

pricing of credit due to the additional regulatory burden may fortify the trend

toward financial exclusion, i.e. more households and businesses withdraw

from borrowing as their cost of funding becomes exorbitant due to cost of

these new regulations. Pakistan has therefore to be careful in designing new

regulations as the coverage of regulatory waterfront is quite extensive and

there are no apparent significant holes. The shadow banking system in

Pakistan is theoretically covered by extensive regulations. It is another story

that in practice there is a wide gap between the supervision of the banks and

non-bank financial institutions. But this should not lead us to the wrong path.

We dont have to necessarily follow all that Dodd-Frank legislation or the EU

38

SBP Research Bulletin, Vol. 7, No. 1, 2011

rules are going to stipulate and prescribe. With very little space for financial

innovation available in this country, treading on the path of the U.S. or Europe

would do great harm by destroying even this limited space and shutting doors

for sensible and benign innovations in the future. Basel III has to be applied

not mindlessly but after testing, adaptation and modifications to suit

Pakistans own requirements.

iii) Consolidation of regulation and supervision

The relationship between regulators and consolidated financial institutions

will be impacted by the relative skills, organizational capacity and managerial

abilities of the regulatory and supervisory bodies. The SBP has over time

equipped itself with the skills, capacity, enforcement and decision making

tools and, technological resources that places it ahead of other regulatory

bodies. The cultural change that has promoted the values of merit, integrity,

reward for performance and competitive levels of compensation have

minimized the risks of regulatory capture. On the other hand, the SBP has

evolved a trusting partnership with the banks a collective body where it

consults and listens to their viewpoints before making policies, rules and

regulations. At the same time it does not hesitate in taking stern and strong

penal actions against individual banks found guilty of infractions and

violations of the regulations. The Supreme Courts historic verdict of

upholding the governors decision to suspend the first ever banking license in

the history of the country has conferred a powerful instrument in the hands of

the SBP and has thus created a strong deterrence effect. The new legislation

pending with the Parliament will further enhance the legal powers of the SBP

for disciplining the recalcitrant owners and managers of the banks. On the

other hand, the SECP that has been given the task of regulating and

supervising non-bank financial institutions (NBFIs) 5-10 percent of the total

assets of the financial system has not been able to equip itself so well. Thus,

in cases where financial conglomerates are emerging on the scene which

would bring banking, investment banking, asset management, insurance, etc.,

under one umbrella there is an urgent need to have a consolidated regulator

and supervisor. Leaving aside the turf fights an objective appraisal would

suggest that this function can best be performed by the SBP. In defense of this

argument we can draw comfort from the fact that the new coalition

government in U.K. has decided to abolish FSA and give back the regulatory

powers back to the Bank of England.

iv) Legal infrastructure

Despite the fact that Pakistan has a Banking Companies Ordinance in force for

quite some time, separate banking courts and tribunals to adjudicate the cases,

Ishrat Husain

39

a Banking Ombudsman to settle disputes between customers and the banks

and the National Accountability Bureau to take action against those indulging

in malfeasance the legal infrastructure for financial sector has been found

wanting in many respects. Billions of rupees of loans are stuck because of the

protracted litigation, delays, adjournments and stay orders granted by the

courts. Where the decrees have been awarded in favor of the banks the speed

of execution is too slow and recovery quite poor. A new Foreclosure Law that

enabled the banks to recover their dues without recourse to the courts in

certain instances has become ineffective as one of the Courts has suspended

its operation. Bankruptcy Law that should have come into effect to allow

orderly settlement of bank loans at the time of the cessation of ongoing

concern has not yet seen the light of the day. The SBP Act that strengthens the

legal and enforcement powers of the central bank has not yet been passed by

the Parliament. The Act on De-mutualization of stock exchanges that will

remove the conflict of interest in the governance and ownership structure of

the stock exchanges is kept pending due to pressures from vested interests.

These weaknesses in the legal infrastructure are a major impediment in the

way of financial sector efficiency and outreach and have to be removed sooner

than later.

v) Credit rating agencies

Another glaring example of infrastructure deficiency exposed by the recent

crisis is the inherent flaw in the well established credit rating agencies that

have driven the process of risk management in the financial sector. The subprime mortgage market was fuelled by the credit rating agencies certifying

securitized tranches of individual loans of weak credit to be safe. The financial

institutions such as the insurance companies and hedge funds bought these

securities because of this certification. Until the 1970s the credit rating

agencies sold their assessments of credit risk to their subscribers only. But

regulatory change introduced by the U.S. SEC in 1975 allowed that the credit

risk assessment of these agencies would be used in establishing capital

requirements on SEC regulated financial institutions. This change was

adopted by other regulators, official agencies and private institutions for the

issue of securities, private endowments, foundations and mutual funds for

asset allocation. Naturally, this led to an expansion in the demand for credit

ratings by these agencies. These credit rating agencies shifted their business

model from selling to subscribers only to selling to issuers of securities. This

conflict of interest, it was argued, can be contained because the companies

would care for preserving their reputational capital which would suffer if they

indulged in malpractices or misuse in awarding ratings. However, this

theoretical assumption proved to be wrong as the explosive growth of

40

SBP Research Bulletin, Vol. 7, No. 1, 2011

structured and securitized financial products particularly their packaging and

rating intensified the conflict of interest problem. In Pakistan, there are only

two rating agencies but limited competition and conflict of interest

considerations dictate that a more robust and reliable system has to take its

place.

vi) Minimum capital requirements and capital adequacy

The Minimum Capital Requirements (MCR) and Risk-Weighted Capital

Adequacy Ratios (CAR) should be interpreted carefully and linked to the

purposes for which they have been devised. The banks are obliged to meet

minimum levels of capital to reduce the costs if the banks fail. They also

should have a capital buffer to continue their operations when they suffer

losses. The MCR is a signal for the weak banks with low equity capital, poor

human resources, rudimentary technology, limited network, fewer products

and services that these banks will have either to increase their equity capital

base or merge with other banks in order to survive or exit from the industry.

About twenty banks in Pakistan account for more than 90 percent of banking

business while the remaining twenty for less than 10 percent. These weak

banks are highly vulnerable to exogenous shocks and their failures can cause

tremors for the banking system imposing unnecessary burden on public

finances (in case it is decided to bail them out) or on their depositors who may

lose faith in the banking system and could trigger a run on other banks

deposits. In all fairness, owners and shareholders of these banks ought to bear

this burden and MCR stipulation is aimed at transferring this burden to the

shareholders in the event of bank failure. Capital Adequacy Ratio (CAR), on

the other hand, establishes the link between equity capitals the bank holds in

relation to its assets that have different risk weights. An observed rise in the

CAR without understanding its underlying dynamics may lead to misleading

conclusions. In Pakistan, the aggregate risk-weighted CAR of the banking

system has risen to 14 percent as compared to the minimum required ratio of

10 percent. This change in the ratio may give a false impression to a nave

observer that the capital strength of the banks has improved. In actual fact, this

higher observed ratio has risen due to a shift in the asset composition of the

banks away from riskier private sector loans to zero or low risk weighted

lending to public sector agencies, quasi-fiscal financing and investment in

government securities. This distortion in the allocation of banks assets away

from productive sectors to financing government deficits is nothing to be

celebrated about and as a matter of fact should be discouraged.

Ishrat Husain

41

vii) Financial inclusion and diversification of assets, products, services and

customers

It is a matter of concern that there has been a slowdown in financial deepening

in Pakistan in the recent years. M2 to GDP ratio that had risen from 36.6

percent to 46.7 percent by FY07 has fallen to 40.1 percent by FY11 and

private sector credit to GDP ratio that had reached 28.5 percent in FY07 from

17.8 percent is now down to 20.6 percent. Consequently, accumulated

financial savings as a proportion of GDP have fallen from the peak of 67.4

percent to 53.1 percent and domestic savings ratio from 18.1 percent to 9.9

percent.4 These trends are disturbing as they imply increased dependence on

uncertain, highly volatile foreign savings and / or a reduced level of

investment rate. In an economy that has been stagnating for last three years it

would be highly damaging if the investment rate is allowed to decline and

GDP and per capita incomes consequently stagnate.

The injection of almost Rs.300400 billion in the rural economy through

higher producer prices of major agricultural crops and livestock products in

last two years can be tapped by the banks and financial institutions as a source

of financial savings. Of course, a large chunk of this will translate into

additional purchasing power that will propel demand for consumer goods but

at least one-third of the additional incomes can be mobilized in form of

savings by microfinance banks, specialized banks, mutual funds and rural

branches of commercial banks. The mobilization of these savings can also be

used by the financial institutions to diversify their assets, products, services

and customer base making greater use of easily accessible technology such as

mobile phones. This will not only avoid concentration of risks in particular

sector or counter parties but diversified portfolios suffer lower losses. Large

segments of the economy, population and geography remain underserved by

the organized financial system. There is need to extend the reach of the

financial system and better serve small entrepreneurs and households,

especially in the SME, agriculture and service sectors which account for most

of the countrys GDP and employment generation but presently receive a

relatively small share of total credit5. The objective of financial inclusion can

best be served by penetrating these geographical areas that have not so far

been reached by the financial institutions. Islamic banking, low cost housing

finance and microfinance are the attractive routes through which the aim of

financial inclusion can be served. There is a growing demand for Islamic

4

5

State Bank of Pakistan (2010), Financial Stability Review 2009-10 (December).

State Bank of Pakistan (2008), Pakistan 10-year Strategy paper for the Banking Sector Reform.

42

SBP Research Bulletin, Vol. 7, No. 1, 2011

Microfinance with attractive products that can cater to the needs of those at

the bottom of the pyramid.

Infrastructure financing and housing finance are other products which have

not yet taken off in Pakistan. There is a real problem for the banks of

mismatch between their short term deposits and long term loans for these

sectors. But REITS, pension funds, provident funds, endowment funds,

municipal bonds, insurance companies and long-term Islamic Sukuk can

resolve this problem and fill in the gap. The progress in this field has so far

been too slow. A more proactive regulatory stance is badly needed to nurture

these two types of products.

viii)Risk management

The crisis also revealed clearly that the models used by the banks and

financial institutions to capture the real risks were either flawed or inadequate.

There was not sufficient available data in regard to the new instruments. The

behavioral relationships based on the past observed data proved to be unstable

or invalid under the pressure points triggered by the crisis. The underlying

assumptions and the estimated probabilities turned out to be wrong. Sudden,

abrupt and quantum changes in asset prices and their consequences for

liquidity and solvency were never taken into account in these risk models.

Underestimation of optimistic calculation of risks also led to under pricing of

risks, a more relaxed credit extension regime and unsustainable leverage

levels. With the hindsight, after the enormous damages were caused to the

financial system across the globe it became apparent that if that the models

used by the financial institutions were correctly calibrated they could have

revealed amplification rather than mitigation of risks.

In Pakistan, risk management is still in its infancy and therefore it wont be

too difficult for the regulators to introduce new risk measures such as leverage

ratio and new risk models. The limited leverage ratio would make it difficult

for the boards managements and others to indulge in excessive risk taking on

the strength of borrowed money. The allocation of risks between the owners

and shareholders of the financial institutions and the society, particularly tax

payers, would thus undergo a change. Under Basel III rules, capital

requirements for trading book exposures, complex securitizations and

exposure to off-balance sheet vehicles have to be enhanced substantially, for

better risk coverage

Ishrat Husain

43

ix) Capacity building of regulator

It must be remembered that the change of ownership from public sector

owned and managed to privatized banks, imposes new burden on the

regulators. As the private owners and managers of the banks have limited

stakes of their own (6 to 8 percent of equity in the total capital available for

deployment) they can take excessive risks with depositors money. The upside

potential from this excessive risk taking will be appropriated solely by the

owners (large dividends) and the managers (high performance bonuses) but

the downside risks will fall upon the shoulders of the depositors or the state.

The regulator has thus to remain vigilant all the time to ensure that the private

owners and management of the banks do operate within the defined risk

parameters, observe the standards, guidelines and codes diligently, comply

with prudential regulations and norms, follow the best corporate governance

practices and do not deviate from the instructions given from time to time.

The competencies and caliber of the staff working in the regulatory

institutions, the use of technology to produce an updated management

information system on real time and the re-engineering of business processes

and systems are the tools whereby the regulators can remain on the top of the

potential problems.

The other challenge for the regulators in the coming years will be to keep pace

with the financial innovations and comprehend the risks involved in these

complex products. The tendency to keep all these complex products off the

market may be an easy way out, but a serious damage will be done to the

growth of financial markets and products that may retard the process of

competitiveness and efficiency in the financial sector. The way forward is to

develop capacity within the SBP to understand and assess the content,

characteristics, embedded risks and the accounting of this ever growing array

of financial instruments particularly derivatives, hedge products and other

similar products that are likely to appear in the future. The regulators have to

insist that there are common standards for valuation of assets and liabilities

(whether mark-to-market accounting should be applied across-the-board) and

there are common yardsticks for measurement. The transparency and

disclosure standards have to be kept under constant watch and suitably upgraded so that the innovations are obligated to furnish the full range of

information required evaluating the risks. While the regulators should not

stifle financial innovation from flourishing, they should have the capacity to

understand the risks and make the market participants aware of these risks.

44

SBP Research Bulletin, Vol. 7, No. 1, 2011

Conclusion

Pakistans regulatory framework has withstood the test of time well since the

reforms were implemented. But as time passes it had to be modified and

strengthened to meet the future challenges in a way that it does not stifle

innovation and growth, does not severely raise the cost and access to credit and

does not constrain the process of financial inclusion. Nor should it be so rigid that

it enables the market players to circumvent the regulations and pursue alternatives

that are less desirable. A balancing act, quite difficult to achieve in practice, will

be required to meet the objectives of financial stability, growth and financial

inclusion.

Bibliography

Akhtar, Shamshad (2007). Pakistan: Regulatory and Supervisory Framework.

Institute of International Bankers, Washington D.C., March 5.

Asian Development Bank (2009). Is Recovery Taking Hold in Developing Asia.

Special Note. December.

Davies, Howard (2010). The Financial Crisis: Whos to blame? Polity Press.

Husain, Ishrat (2003). Regulatory Strategy of the State Bank of Pakistan.

Annual Conference of Pakistan Society of Development Economics,

Islamabad, January 15.

Husain, Ishrat (2009). Preserving Access to Finance during the Global Crisis.

KFW Symposium, Berlin, December.

IMF (2009). World Economic Outlook, October.

IMF (2009). Global Financial Stability Report, October.

Levine, Ross (2010). The Governance of Financial Regulation: Reform Lessons

from the Recent Crisis. BIS Working Paper329, November.

Monteil, Peter (2010). Lessons from Great Recession. Unpublished draft.

Poulson, Hank (2009). Wire News Stories.

Raza, Syed Salim (2009). Current Crisis and the Future of Financial Regulation.

Institute of Bankers Pakistan, Karachi, October 21.

State Bank of Pakistan (2008). Pakistan 10 year Strategy Paper for the Banking

Sector Reform.

State Bank of Pakistan (2010). Financial Stability Review 2009-10, December.

Trichet, Jean Claude (2009). Financial Times, November.

Wellink, Nout (2010). A New Regulatory Landscape, BIS Review 154/2010.

WickmanPark, Barby (2010). New International Regulations for Banks A

Welcome Reform, BIS Review 159/2010.

You might also like

- Standards For Crisis PreventionDocument17 pagesStandards For Crisis Preventionanon_767585351No ratings yet

- Emerging Challenges To Financial StabilityDocument13 pagesEmerging Challenges To Financial StabilityRao TvaraNo ratings yet

- The Need For Minimum Capital Requirement: spl/gjfmv6n8 - 12 PDFDocument36 pagesThe Need For Minimum Capital Requirement: spl/gjfmv6n8 - 12 PDFMaitreyeeNo ratings yet

- Rbi PDFDocument28 pagesRbi PDFRAGHUBALAN DURAIRAJUNo ratings yet

- Lessons of The Financial Crisis For Future Regulation of Financial Institutions and Markets and For Liquidity ManagementDocument27 pagesLessons of The Financial Crisis For Future Regulation of Financial Institutions and Markets and For Liquidity ManagementrenysipNo ratings yet

- Yes, We Need A Central Bank: January 2002Document5 pagesYes, We Need A Central Bank: January 2002Therese Grace PostreroNo ratings yet

- Malaysia - Financial Stability and Payment Systems Report - 2018Document160 pagesMalaysia - Financial Stability and Payment Systems Report - 2018Krit KPNo ratings yet

- Theme Paper and Special ReportsDocument48 pagesTheme Paper and Special ReportsowltbigNo ratings yet

- Financial InstitutionDocument17 pagesFinancial InstitutionAbhishek JaiswalNo ratings yet

- Speech 140110Document6 pagesSpeech 140110ratiNo ratings yet

- Web Lesson 1Document3 pagesWeb Lesson 1api-3733468No ratings yet

- Speech BISDocument12 pagesSpeech BISrichardck61No ratings yet

- Banking Sector Reforms in Bangladesh: Measures and Economic OutcomesDocument25 pagesBanking Sector Reforms in Bangladesh: Measures and Economic OutcomesFakhrul Islam RubelNo ratings yet

- Management of Financial InstitutionDocument172 pagesManagement of Financial InstitutionNeo Nageshwar Das50% (2)

- Monetary Economics UZ Individual FinalDocument10 pagesMonetary Economics UZ Individual FinalMilton ChinhoroNo ratings yet

- Post-Crisis: The New NormalDocument16 pagesPost-Crisis: The New NormalRohit DeshmukhNo ratings yet

- Answers To Questions: MishkinDocument8 pagesAnswers To Questions: Mishkin?ᄋᄉᄋNo ratings yet

- Assignment 4 - Tee Chin Min BenjaminDocument1 pageAssignment 4 - Tee Chin Min BenjaminBenjamin TeeNo ratings yet

- Solved Paper FSD-2010Document11 pagesSolved Paper FSD-2010Kiran SoniNo ratings yet

- Framework Chap7 - NepalDocument38 pagesFramework Chap7 - NepalMèoMậpNo ratings yet

- Non Banking Financial InstitutionsDocument10 pagesNon Banking Financial InstitutionsJyothi SoniNo ratings yet

- 2010 09 RGE Steps We Must Take After Dodd FrankDocument2 pages2010 09 RGE Steps We Must Take After Dodd FrankgsnithinNo ratings yet

- Tutorial Sheet 2Document7 pagesTutorial Sheet 2kinikinayyNo ratings yet

- Bank Concentration: Cross-Country Evidence: Asli Demirguc-Kunt and Ross LevineDocument32 pagesBank Concentration: Cross-Country Evidence: Asli Demirguc-Kunt and Ross LevineAsniNo ratings yet

- Comparative Performance of Conventional Stock Index and Islamic Stock Index An Empirical Investigation of Capital Market of PakistanDocument15 pagesComparative Performance of Conventional Stock Index and Islamic Stock Index An Empirical Investigation of Capital Market of PakistanMateenNo ratings yet

- T R A N S F O R M A T I O N: THREE DECADES OF INDIA’S FINANCIAL AND BANKING SECTOR REFORMS (1991–2021)From EverandT R A N S F O R M A T I O N: THREE DECADES OF INDIA’S FINANCIAL AND BANKING SECTOR REFORMS (1991–2021)No ratings yet

- Regulating The Finansial SectorDocument18 pagesRegulating The Finansial SectorThalia KaduNo ratings yet

- EIB Working Papers 2019/10 - Structural and cyclical determinants of access to finance: Evidence from EgyptFrom EverandEIB Working Papers 2019/10 - Structural and cyclical determinants of access to finance: Evidence from EgyptNo ratings yet

- Building The Index of Resilience For Islamic Banking in Indonesia: A Preliminary ResearchDocument32 pagesBuilding The Index of Resilience For Islamic Banking in Indonesia: A Preliminary ResearchYasmeen AbdelAleemNo ratings yet

- Liquidity Management and Commercial Banks' Profitability in NigeriaDocument16 pagesLiquidity Management and Commercial Banks' Profitability in NigeriaPrince KumarNo ratings yet

- Financial Stability and Islamic Finance:: Ishrat HusainDocument8 pagesFinancial Stability and Islamic Finance:: Ishrat HusainDrNaWaZ DurRaniNo ratings yet

- FIM Reforming IndiaDocument14 pagesFIM Reforming IndiaRanjita NaikNo ratings yet

- 1437 AjafDocument29 pages1437 AjafNafis AlamNo ratings yet

- Macroeconomics Assignment 4Document2 pagesMacroeconomics Assignment 4Tharani NagarajanNo ratings yet

- Governance 29 May 06 PDFDocument10 pagesGovernance 29 May 06 PDFrehanNo ratings yet

- FM 105 - Banking and Financial Institutions: Expanding BSP's Regulatory Power Under The New Central Bank ActDocument23 pagesFM 105 - Banking and Financial Institutions: Expanding BSP's Regulatory Power Under The New Central Bank ActKimberly Solomon JavierNo ratings yet

- Toward A Theory of Optimal Financial StructureDocument30 pagesToward A Theory of Optimal Financial StructuremaxNo ratings yet

- Global Financial Crisis and Key Risks: Impact On India and AsiaDocument27 pagesGlobal Financial Crisis and Key Risks: Impact On India and AsiahemantNo ratings yet

- Economics - Ijecr - Efects of Capital Adequacy On TheDocument10 pagesEconomics - Ijecr - Efects of Capital Adequacy On TheTJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- Major BankingDocument14 pagesMajor Bankinghector de silvaNo ratings yet

- IMF Public Debt ManagementDocument37 pagesIMF Public Debt ManagementTanisha singhNo ratings yet

- World Ec Region 2013Document46 pagesWorld Ec Region 2013Alexandru GribinceaNo ratings yet

- The International Lender of Last ResortDocument28 pagesThe International Lender of Last ResortchalikanoNo ratings yet

- 9506 11826 1 PB PDFDocument9 pages9506 11826 1 PB PDFNaisonGaravandaNo ratings yet

- Bank of England, Tha Role of Macroprudential PolicyDocument38 pagesBank of England, Tha Role of Macroprudential PolicyCliffordTorresNo ratings yet

- Effects of Global Financial CrisisDocument10 pagesEffects of Global Financial CrisisHusseinNo ratings yet

- Classens, K. and Van Horen, N. (2012) Foreign Banks: Trends, Impact and Financial Stability', IMF Working Paper, International Monetary FundDocument4 pagesClassens, K. and Van Horen, N. (2012) Foreign Banks: Trends, Impact and Financial Stability', IMF Working Paper, International Monetary FundMinh VănNo ratings yet

- WP 146Document22 pagesWP 146Никита АкимовNo ratings yet

- International Monetary Financial Economics 1st Edition Daniels Solutions ManualDocument8 pagesInternational Monetary Financial Economics 1st Edition Daniels Solutions Manualhypatiadaisypkm100% (29)

- Financial Sector of Pakistan - The Roadmap: Dr. Shamshad AkhtarDocument7 pagesFinancial Sector of Pakistan - The Roadmap: Dr. Shamshad AkhtarpunjabsaraNo ratings yet

- Banking SectorDocument29 pagesBanking SectormagimaryNo ratings yet

- R Eview of The Bank 'S Investm Ent Policy: Expert Panel ReportDocument25 pagesR Eview of The Bank 'S Investm Ent Policy: Expert Panel Reportmlnarayana1215447No ratings yet

- Regulations and Financial StabilityDocument7 pagesRegulations and Financial StabilityRelaxation MusicNo ratings yet

- Central Banking SummaryDocument15 pagesCentral Banking SummaryLe ThanhNo ratings yet

- Bank Failure Causes and Consequences in Nigeria SeminarDocument13 pagesBank Failure Causes and Consequences in Nigeria SeminarGabrielNo ratings yet

- Tobin Brainard PDFDocument19 pagesTobin Brainard PDFRejaneFAraujoNo ratings yet

- BKG System Review (2003)Document101 pagesBKG System Review (2003)AyeshaJangdaNo ratings yet

- Macroprudential Supervision of Financial InstitutionsDocument17 pagesMacroprudential Supervision of Financial InstitutionsDennis LiuNo ratings yet

- Eco Dev MidtermDocument6 pagesEco Dev MidtermGlenn VeluzNo ratings yet

- WegagenDocument63 pagesWegagenYonas100% (1)

- Intro To Research PDFDocument19 pagesIntro To Research PDFshaikh javedNo ratings yet

- Chap # 1 - Introduction To Entrepreneurship (Edited)Document41 pagesChap # 1 - Introduction To Entrepreneurship (Edited)shaikh javedNo ratings yet

- AnnouncementsDocument36 pagesAnnouncementsshaikh javedNo ratings yet

- Porters Five Force ModelDocument3 pagesPorters Five Force Modelshaikh javedNo ratings yet

- Basic Research: Presented by Manu AliasDocument11 pagesBasic Research: Presented by Manu Aliasshaikh javedNo ratings yet

- Chap # 1 - Introduction To Entrepreneurship (Edited)Document41 pagesChap # 1 - Introduction To Entrepreneurship (Edited)shaikh javedNo ratings yet

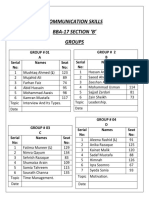

- Communication Skills Bba-17 Section B' GroupsDocument2 pagesCommunication Skills Bba-17 Section B' Groupsshaikh javedNo ratings yet

- Shaheed Benazir Bhutto University, Shaheed BenazirabadDocument1 pageShaheed Benazir Bhutto University, Shaheed Benazirabadshaikh javedNo ratings yet

- Difference Between International, Multinational and Global CompaniesDocument1 pageDifference Between International, Multinational and Global Companiesshaikh javedNo ratings yet

- Shaheed Benazir Bhutto University, Shaheed BenazirabadDocument1 pageShaheed Benazir Bhutto University, Shaheed Benazirabadshaikh javedNo ratings yet

- Javed Ahmed Shaikh: Chapter 1-Slide 1Document19 pagesJaved Ahmed Shaikh: Chapter 1-Slide 1shaikh javedNo ratings yet

- None of AboveDocument4 pagesNone of Aboveshaikh javedNo ratings yet

- Research Methods Chapter #09Document39 pagesResearch Methods Chapter #09shaikh javedNo ratings yet

- Subject: Application For The Post of Management TraineeDocument1 pageSubject: Application For The Post of Management Traineeshaikh javedNo ratings yet

- Od HeadsDocument1 pageOd Headsshaikh javedNo ratings yet

- Performance AppraisalDocument7 pagesPerformance Appraisalshaikh javedNo ratings yet

- Distribution Channels, Roles of Sales Teams/Branch Bankers & Retention of TeamsDocument14 pagesDistribution Channels, Roles of Sales Teams/Branch Bankers & Retention of Teamsshaikh javedNo ratings yet

- Rewards and Employee Motivation-Nirma UniversityDocument17 pagesRewards and Employee Motivation-Nirma Universityshaikh javed100% (1)

- The Crisis of Internally Displaced Persons (Idps) in The Federally Administered Tribal Areas of Pakistan and Their Impact On Pashtun WomenDocument26 pagesThe Crisis of Internally Displaced Persons (Idps) in The Federally Administered Tribal Areas of Pakistan and Their Impact On Pashtun Womenshaikh javedNo ratings yet

- Ram Charan FortuneDocument10 pagesRam Charan Fortuneshaikh javedNo ratings yet

- SMP Report On Tapal TeaDocument48 pagesSMP Report On Tapal Teashaikh javedNo ratings yet

- BF CS Credit Card Cross Sell WEB 0Document2 pagesBF CS Credit Card Cross Sell WEB 0shaikh javedNo ratings yet

- TD Beyond Checking: Account SummaryDocument4 pagesTD Beyond Checking: Account SummaryAlanNo ratings yet

- Paxum Personal Account FeesDocument5 pagesPaxum Personal Account FeesFarid PrimadiNo ratings yet

- List of Fixed Deposit Schemes For The Month of Jul 2019Document3 pagesList of Fixed Deposit Schemes For The Month of Jul 2019gautham28No ratings yet

- Chap 6 Aa015 Sa Objective Q For BuddiesDocument4 pagesChap 6 Aa015 Sa Objective Q For BuddiesCHUAH CHEE XIAN MoeNo ratings yet

- OB David Weekley Homes FinalDocument7 pagesOB David Weekley Homes FinalBobNo ratings yet

- Management Information System of State Bank of India and Its Associate BanksDocument13 pagesManagement Information System of State Bank of India and Its Associate BanksSushil Goyal75% (4)

- Main Types of Foreign Exchange RatesDocument5 pagesMain Types of Foreign Exchange RatesVaibhav BhatnagarNo ratings yet

- Plat Bus Checking (... 2179)Document1 pagePlat Bus Checking (... 2179)AmirniteNo ratings yet

- FN107 1342Document1,037 pagesFN107 13421202104554No ratings yet

- Memorandum of Agreement: I. Purpose & ScopeDocument3 pagesMemorandum of Agreement: I. Purpose & ScopethatcatwomanNo ratings yet

- Customer StatementDocument5 pagesCustomer StatementDarius Murimi NjeruNo ratings yet

- Cash Management ServicesDocument5 pagesCash Management ServicesMadhur AnandNo ratings yet

- MCQ in Principles of InsuranceDocument27 pagesMCQ in Principles of InsuranceDrJay Trivedi71% (17)

- Tanzania Banking Survey 2012 FINAL July 2012Document144 pagesTanzania Banking Survey 2012 FINAL July 2012Fred Raphael IlomoNo ratings yet

- Grace PeriodDocument2 pagesGrace PeriodHaider UsmanNo ratings yet

- Buildings Insurance - What Does A Good Policy Look LikeDocument3 pagesBuildings Insurance - What Does A Good Policy Look Likepaul murphyNo ratings yet

- Domestic Tax Laws of Uganda 2016. Updated and Tracked Compendium.Document370 pagesDomestic Tax Laws of Uganda 2016. Updated and Tracked Compendium.URAuganda100% (8)

- Challenges Faced by Banking Industry: AssignmentDocument7 pagesChallenges Faced by Banking Industry: Assignmentkirtan patelNo ratings yet

- Loan Disbursement HandbookDocument139 pagesLoan Disbursement Handbooklongriver28284No ratings yet

- IO!oi'PP/ ': I I I I IIDocument1 pageIO!oi'PP/ ': I I I I IISyed Qaisar ImamNo ratings yet

- Rural BankingDocument6 pagesRural BankingERAKACHEDU HARI PRASAD0% (1)

- WeChat Addendum (Stamped)Document2 pagesWeChat Addendum (Stamped)Marven John BusqueNo ratings yet

- The Commercial Observer - May 11, 2010Document55 pagesThe Commercial Observer - May 11, 2010Jesse CostelloNo ratings yet

- The Guest Cycle in HotelDocument3 pagesThe Guest Cycle in HotelAnonymous oY0VrepuOMNo ratings yet

- Sample Employment ContractsDocument14 pagesSample Employment ContractsPriya Shah100% (1)

- CSIR Local Supplier Registration FormDocument3 pagesCSIR Local Supplier Registration FormwiwuweNo ratings yet

- Wu Tang Financial Excel SpreadsheetDocument16 pagesWu Tang Financial Excel SpreadsheetJason BurgoyneNo ratings yet

- Another Positive Surprise: Bursa MalaysiaDocument8 pagesAnother Positive Surprise: Bursa MalaysiaYGNo ratings yet

- Insurance - Midterms Case DoctrinesDocument7 pagesInsurance - Midterms Case DoctrinescamilleholicNo ratings yet

- Pacific & Orient Insurance Co BHD: Premium Polisi (RM)Document2 pagesPacific & Orient Insurance Co BHD: Premium Polisi (RM)Mohamad HamidNo ratings yet