Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Fullan Jec Future of Educational Change

Uploaded by

api-275150179Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Fullan Jec Future of Educational Change

Uploaded by

api-275150179Copyright:

Available Formats

J Educ Change (2006) 7:113122

DOI 10.1007/s10833-006-9003-9

ORIGINAL PAPER

The future of educational change: system thinkers

in action

Michael Fullan

Received: 1 May 2006 / Accepted: 2 May 2006 /

Published online: 6 September 2006

Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2006

Abstract In addressing the future agenda of educational change, this paper

advances the notion of sustainability as a key factor in developing a new kind of

leadership. This new leadership, if enduring, large scale change is desired, needs to

go beyond the successes of increasing student achievement and move toward leading

organizations to sustainability. Currently, there is a lack of development of leaders

toward system thinking. An argument is made for linking systems thinking with

sustainability in order to transform an organization or a system. In order to

accomplish this goal, it is necessary to change not only individuals but also systems.

The way to change systems is to foster the development of practitioners who are

system thinkers in action. Such leaders widen their sphere of engagement by

interacting with other schools in a process we call lateral capacity building. When

several leaders act this way they actually change the context in which they work.Eight elements of sustainability, which will enable leaders to become more effective

at leading organizations toward sustainability, are presented. Within the explication

of the eight elements, prior research is considered, difficulties are surfaced, and

challenges are issued to change contextual conditions in order to effect large scale,

sustainable educational change.

In this paper I focus on the future agenda of educational change. The premise is that

the existing knowledge base has not yet pushed far enough into action. Stated differently, those working in the field of educational change have not provided us with a

powerful enough agenda for actually realizing deeper reform. It is not sufficient to

critique policies or even to offer great insights into current situations. We should

push further into what Perkins (2003) calls action poetry:

Adapted from an address at American Educational Research Association Annual Meeting, 2004.

M. Fullan (&)

Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

e-mail: mfullan@oise.utoronto.ca

123

114

J Educ Change (2006) 7:113122

Action poetry: The language of real change needs not just explanation theories, or even action theories, but good action poetry action theories that are

built for action-simple, memorable, and evocative (p 213)

I take up the challenge here by arguing that we need to focus on the conditions for

sustainability and the leadership that will be necessary to create those conditions. I

define sustainability as the capacity of a system to engage in the complexities of

continuous improvement consistent with deep values of human purpose (Fullan,

2005, p. ix)

Andy Hargreaves and Finks groundbreaking definition of sustainability, that is

compatible with this is sustainability does not simply mean whether something will

last. It addresses how particular initiatives can be developed without compromising

the development of others in the surrounding environment now and in the future

(Hargreaves & Fink, 2006, p. 30)

In this paper I claim that the key to establishing sustainability lies in the fostering

and proliferation of a fundamentally new kind of leadership in action. Such leadership requires conceptual thinking that is grounded in creating new contexts. New

practitioners of this leadership and those working with them are decidedly not

armchair theorists; nor are they simply leaders in the trenches. In Heifetz and

Linskys (2002) phrase, they have the capacity to be simultaneously on the dance

floor and the balcony.

Thus, to go further we need to develop a new kind of leadershipwhat I call

system thinkers in action or the new theoreticians. These are leaders who work

intensely in their own schools or districts or other levels, and at the same time connect

with and participate in the bigger picture. To change organizations and systems will

require leaders who get experience in linking to other parts of the system. These

leaders in turn must help develop other leaders with similar characteristics. In this

sense, the main mark of a school principal, for example, is not the impact he or she has

on the bottom line of student achievement at the end of their tenure but rather how

many good leaders they leave behind who can go even further. The question, then, is

how can we practically develop system thinkers in action? Some do exist but how do

we get them in numbersa critical mass needed for system breakthrough.

I do not think we have made any progress in actually promoting systems thinking

in practice since Senge (1990) first raised the matter. As Senge laid out the argument:

... human endeavors are also systems. They ... are bound by invisible fabrics of

interrelated actions, which often take years to fully play out their effects on each

other. Since we are part of the lacework work ourselves, it is doubly hard to see

the whole pattern of change. Instead, we tend to focus on snapshots of isolated

parts of the system, and wonder why our deepest problems never seem to get

solved. Systems thinking is a conceptual framework, a body of knowledge and

tools that has been developed over the past fifty years, to make the full patterns

clearer, and to help us see how to change them effectively. (Senge, 1990, p. 7, my

emphasis)

We will come back to the italics later, but most of us will recall that systems thinking

is the fifth discipline that integrates the other four disciplines: personal mastery,

mental models, building shared vision, and team learning.

Philosophically, Senge is on the right track but it doesnt seem to be very helpful

in practice:

123

J Educ Change (2006) 7:113122

115

[Systems thinking] is the discipline that integrates the disciplines, fusing them

into a coherent body of theory and practice. It keeps them from being separate

gimmicks or the latest organization fads. Without a systemic orientation, there

is no motivation to look at how the disciplines interrelate ...

At the heart of a learning organization is a shift of mindfrom seeing ourselves as separate from the world to connected to the world, from seeing

problems as caused by someone or something out there to seeing how our

own actions create the problems we experience. A learning organization is a

place where people are continually discovering how they create their reality

and how they can change it. (pp. 12, 13, my emphasis)

As valid as the argument may be, I know of no program of development that has

actually developed leaders to become greater, practical systems thinkers. Until we

do this we cannot expect the organization or system to become transformed. The key

to doing this is the to link systems thinking with sustainability. The question in this

article is whether organizations can provide training and experiences for their

leaders that will actually increase their ability to identify and take into account

system context. If this can be done it would make it more likely that systems, not just

individuals could be changed.

Heifetz (2003) makes a distinction between technical problems (for which we

know the answer) and adaptive challenge (for which solutions lie outside our current

repertoire). Developing system thinkers is an adaptive challenge. The key to moving

forward is to enable leaders to experience and become more effective at leading

organizations toward sustainability. In Fullan (2005) I define eight elements of

sustainability:

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

Public service with a moral purpose

Commitment to changing context at all levels

Lateral capacity-building through networks

New vertical relationships that are co-dependent encompassing both capacitybuilding and accountability

Deep learning

Dual commitment to short-term and long-term results

Cyclical energizing

The long lever of leadership

Public service with a moral purpose

In examining moral purpose (Fullan, 2003b) I have talked about how it must transcend the individual to become an organization and system quality in which collectivities were committed to pursuing moral purpose in all of their core activities. I

define moral purpose in three ways with respect to schools: (i) commitment to raising

the bar and closing the gap of student achievement; (ii) treating people with respect,

which is not to say low expectations; and (iii) orientation to improving the environment including other schools in the district. Corporate organizations as well as

public institutions must embrace moral purpose if they wish to succeed over the long

run.

123

116

J Educ Change (2006) 7:113122

Commitment to changing context at all levels

Hargreaves (2003) reminds us of Donald Schons observation over 30 years ago:

We must ... become adept at learning. We must become able not only to

transform our institutions, in response to changing situations and requirements;

we must invest and develop institutions which are learning systems, that is to

say, systems capable of bringing about their own continuing transformation [in

Hargreaves, p. 74].

It is not Schons fault that 30 years later this advice remains 100% accurate yet of

little practical value. How do you enter the chicken and egg equation of starting

down the path of generating learning systems in practice, especially in an era of

transparent accountability? This article is about providing a practical response to

this question; and there is now more powerful evidence that changing the system

is an essential component of producing learning organizations.

Changing whole systems means changing the entire context within which people

work. Researchers are fond of observing that context is everything, usually in reference to why a particular innovation succeeded in one situation but not another. Well,

if context is everything, we must directly focus on how it can be changed for the better.

Not as impossible as it sounds although it will take time and cumulative effort. The

good news is that once it is underway it has self-generating powers to go further.

Contexts are the structures and cultures within which one works. In the case of

educators, the tri-level contexts are school/community, district, and system. The

question is can we identify strategies that will indeed change in a desirable direction

the contexts that affect us? (Currently these contexts have a neutral or adverse

impact on what we do.)

On a small scale, Gladwell (2000) has already identified context as a key Tipping

Point: the power of context says that what really matters is the little things (p.

150). And if you want to change peoples behavior you need to create a community

around them, where these new beliefs could be practical, expressed and nurtured

(p. 173). Drawing from complexity theory, I have already made the case that if you

want to change systems, you need to increase the amount of purposeful interaction

between and among individuals within and across the tri-levels, and indeed within

and across systems (Fullan, 2003a).

So, we need first of all to commit to changing context. Then at a more practical

level each of the remaining six elements literally gives people new experiences, new

capacities and new insights into what should and can be accomplished. It gives

people a taste of the power of new context, none more so than the discovery of

lateral capacity building.

Lateral capacity-building through networks

In the past few years, lateral capacity has been discovered as a powerful strategy for

school improvement. I say discovery because the sequence was: greater accountability leading to the realization that support or capacity building was essential;

which led to vertical capacity-building with external trainers at the district or other

levels; and then in turn to the realization that lateral capacity-building across peers

was a powerful learning strategy.

123

J Educ Change (2006) 7:113122

117

The most systematic strategy-driven use of networks and collaboratives is

evolving in England, partly as a response to the limitations of informed prescription.

Many of the new network strategies are being developed by the National College of

School Leadership (NCSL). For example, a consultant leaders program now engages

1,000 of the most effective elementary school principals in the country working with

4,000 other schools Thus, in this one strategy alone, 25% of all school principals in

the country are involved in mutual learning.

There are a number of obvious benefits from lateral strategies (see also Hargreaves, 2003). People learn best from peers (fellow travelers who are further down

the road) if there is sufficient opportunity for ongoing, purposeful exchange; the

system is designed to foster, develop and disseminate innovative practices that

workdiscoveries, lets say, in relation to Heifetzs adaptive challenges (solutions

that lie outside the current way of operating); leadership is developed and mobilized in many quarters; motivation and ownership at the local level is deepeneda

key ingredient for sustainability of effort and engagement.

Networks, per se, are not a panacea. The downside possibilities potentially include:

(a) there may be too many of them adding clutter rather than focus, (b) they may

exchange beliefs and opinions more than quality knowledge, and in any case how can

quality knowledge be achieved, and (c) networks are usually outside the line-authority,

so the question is how potential good ideas get out of the networks so to speak and into

focused implementation which requires intensity of effort over time in given settings.

Networks are not ends in themselves but must be assessed in terms of the impact they

have on changing the cultures of schools and districts and the state in the direction of

the eight elements of sustainability identified in this paper.

It is also important to note that lateral capacity is not the only strategy at work (in

particular, the relationship to the other seven elements of sustainability must be

highlighted). Complexity theory tells us that if you increase the amount of purposeful interaction and infuse it with the checks and balances of quality knowledge,

self-organizing patterns (desirable outcomes) will accrue. This promise is not good

enough for the sustainable-seeking society with a sense of urgency. There are at least

two problems. One concerns how the issues being investigated can result in disciplined inquiry and innovative results; the other raises the question of how good ideas

being generated by networks can be integrated in the line operation of organizations.

New vertical co-dependent relationships

Sustainable societies must solve (hold in dynamic tension) the perennial change

problem of how to get both local ownership (including capacity) and external

accountability; and to get this in the entire system. We know that the problems have

to be solved locally:

Solutions rely, at least in part, on the users themselves and their capacity to

take school responsibility for positive outcomes. In learning, health, work, and

even parenting, positive outcomes arise from a combination of personal effort

and wider social resources [Bentley & Wilsdon, 2003, p. 20].

The question is what is going to motivate people to seek positive outcomes, and

when it comes to the public or corporate good, how are people and groups to be held

accountable? The answer is a mixture of collaboration and networks, on the one

123

118

J Educ Change (2006) 7:113122

hand, and what Miliband, former Minister of State for School Standards in Britain

calls intelligent accountability on the other hand. Networks and other professional

learning communities (lateral capacity-building) do build in a strong but not complete measure of accountability. As such communities interact around given problems, they generate better practices, shared commitment and accountability to peers.

Collaborative cultures are demanding when it comes to results, and the demand is

telling because it is peer-based and up close on a daily basis.

Vertical relationships (state/district, district/school, etc.) must also be strengthened. One aspect of vertical relationships involves support and resources; the other

concerns accountability. Some of these will come in the form of element five (deep

learning) and six (short-term and long-term results). It will be difficult to get the

balance of accountability right in terms of vertical authoritytoo much direction

demotivates people; too little permits drift or worse.

To address this problem we need to re-introduce a strategy that has been around

for at least 20 years, namely, self-evaluation. In the past, self-evaluation has been

touted as an alternative to top-down assessment. In fact, we need to conceive selfevaluation and use it as a both/and solution. Miliband (2004) in a recent speech put it

this way in advocating:

An accountability framework, which puts a premium on ensuring effective and

ongoing self-evaluation in every school combined with more focused external

inspection, linked closely to the improvement cycle of the school. [p. 6]

He then proposed:

First, we will work with the profession to create a suite of materials that will help

schools evaluate themselves honestly. The balance here is between making the

process over-prescriptive, and making it just an occasional one-off event. In the

best schools it is continuous, searching and objective. Second, [we] will shortly

be making proposals on inspection, which take full account of a schools selfevaluation. A critical test of the strong school will be the quality of its selfevaluation and how it is used to raise standards. Third, the Government and its

partners at local and national level will increasingly use the information provided by a schools self-evaluation and development plan, alongside inspection,

to inform outcomes about targeting support and challenge. [p. 8]

Despite, Milibands reference to intelligent accountability, three teachers unions

just released a paper advocating that assessment for learning be reclaimed by the

teaching profession. They say, in effect that the governments intelligent accountability does not rely enough on teacher assessment and judgment:

Teacher assessment is at the heart of effective learning. The type of assessment

which best supports learning is that which is based on the day-to-day informed

professional judgments that teachers make about pupils learning achievement

and their learning needs (ATL et al., 2004 p. 2)

Is it possible to reconcile the governments concern about intelligent accountability

and the unions position that assessment must be in the hands of the teaching profession? In any case, it is going to be extremely difficult to combine self-evaluation

and outside evaluation. For sustainability to have a chance the system must be

involved in co-dependent partnerships with leaders of the type discussed here.

123

J Educ Change (2006) 7:113122

119

Deep learning

Sustainability requires continuous improvement, adaptation and collective problemsolving in the face of complex challenges that keep arising. As Heifetz (2003) says,

adaptive work demands learning, demands experimentation, and difficult

conversations. Species evolve whereas cultures learn, says Heifetz (p. 75).

There are three big requirements for the data driven society: drive out fear; set up

a system of transparent data-gathering coupled with mechanisms for acting on the

data; make sure all levels of the system are expected to learn from their experiences.

One of Demings (1986) prescriptions for success was Drive out Fear. In the

Education Epidemic, Hargreaves (2003) argues:

Government must give active permission to schools to innovate and provide a

climate in which failure can be given a different meaning as a necessary element in making progress, as is the case in the business world ... mistakes can be

accepted or even encouraged, provided that they are a means of improvement.

[p. 36]

Pfeffer and Sutton (2000) in the Knowing-Doing Gap devote a whole chapter to

When Fear Prevents Acting on Knowledge in it they note that In organization

after organization that failed to translate knowledge into action, we saw a pervasive

atmosphere of fear and distrust. [p. 109]

Significantly, Pfeffer and Sutton identify two other pernicious effects. One is

that fear causes a focus on the short run [driving] out consideration of the longer

run (pp. 124125). The other problem is that fear creates a focus on the individual

rather than the collective (p. 126). In a punitive culture, if I can blame others, or

others make a mistake, I am better off. Need I say that both the focus on the short

run, and excessive individualism are fatal for sustainability?

Second, capacities and means of acting on the data are critical for learning. Thus,

assessment for learning has become a powerful, high yield tool for school

improvement and student learning (see Black, Harrison, Lee, Marshall, & Wiliam,

2003). Critical aspects of the move toward more effective data use include: (i)

avoiding excessive assessment demands (Miliband talks about reducing necessary

paper and information burden which distract schools from their core business); (ii)

ensure that a range of data are collectedqualitative as well as quantitative. In

Leading in a Culture of Change, I cite several examples including the US Armys

After Action Reviews which have three standardized questions: What was supposed

to happen? What happened? And what accounts for the differences? This kind of

learning is directed to the future, i.e., to sustainable improvements.

Deep learning means collaborative cultures of inquiry, which alter the culture of

learning in the organization away from dysfunctional and non-relationships toward

the daily development of culture that can solve difficult or adaptive problems (see

especially Kegan & Lahey, 2001; Perkins, 2003). The curriculum for doing this is

contained in Kegan and Laheys seven languages for transformation (e.g., from the

language of complaint to the language of commitment), and in Perkins developmental leadership which represents progressive interaction which evokes the exchange of good ideas, and fosters the cohesiveness of the group. These new ways of

working involve deep changes in the culture of most organizations, and thus the

training and development must be sophisticated and intense. Perkins emphasizes

how difficult this is going to be. He makes the case that regressive interaction

123

120

J Educ Change (2006) 7:113122

(poor knowledge exchange, and weak social cohesion) is more likely to occur because it is easier than trying to create the more complex progressive cultures. Be that

as it may, the solution is to develop more and more leaders who can help shape

school system cultures in these directions.

Dual commitment to short-term and long-term results

Like most aspects of sustainability, things that look like they are mutually exclusive

have to be brought together. Its a pipedream to argue only for the long-term goal of

organizations or society, because the shareholders and the public wont let you get

away with it, nor should they. The new reality is that governments and organizations

have to show progress in relation to priorities in the short as well as long-term. Our

knowledge base is such that there is no excuse for failing to design and implement

strategies that get short-term results.

Of course, short-term progress can be accomplished at the expense of the mid to

long-term (win the battle, lose the war), but they dont have to be. What I am

advocating is that organizations set targets and take action to obtain early results,

intervene in situations of terrible performance, all the while investing in the eight

sustainability capacity-building elements described in this article. Over time, the

system gets stronger and fewer severe problems occur as they are pre-empted by

corrective action sooner rather than later.

Shorter-term results are also necessary to build trust with the public or

shareholders for longer-term investments. Barber (2004) argues that it is necessary

to:

Create the virtuous circle where public education delivers results, the public

gains confidence and is therefore willing to invest through taxation and, as a

consequence, the system is able to improve further. It is for this reason that the

long-term strategy requires short-term results.

Cyclical energizing

Sustain comes from the Latin word, sustineo which means to keep up, but this is

misleading. Sustainability on the contrary is not linear. It is cyclical for two fundamental reasons. One has to do with energy, and the other with periodic plateaus

where additional time and ingenuity are required for the next adaptive breakthrough. Loehr and Schwartzs (2003) power of full engagement argue that energy, not time is the fundamental currency of high performance. They base their

work on four principles:

Principle 1: Full engagement requires four separate but related sources of energy:

physical, emotional, mental, and spiritual; [p. 9]

Principle 2: Because energy capacity diminishes both with overuse and with

underuse, we must balance energy expenditure with intermittent energy renewal; [p. 11]

Principle 3: To build capacity, we must push beyond our normal limits, training

in the same systematic way that elite athletes do; [p. 13]

123

J Educ Change (2006) 7:113122

121

Principle 4: Positive energy ritualshighly specific routines for managing energyare key to full engagement and sustained high performance. [p. 14]

If we want sustainability we need to keep an eye on energy levels (overuse and

underuse). Positive collaborative cultures will help because (a) they push for greater

accomplishments, and (b) they avoid the debilitating effects of negative cultures. It is

not hard work that tires us out, as much as it is negative work. In any case, we need

combinations of full engagement with colleagues, along with less intensive activities,

which are associated with replenishment.

There is another reason why sustainability is cyclical. In many cases we have seen

achievement in literacy and mathematics improve over a 5-year period, only to

plateau or level off. It may be related to burnout, but this is not likely the main

explanation. People are still putting in a lot of energy to maintain the same higher

level performance represented by the new plateau. If people were burning out,

performance would likely decline.

A more likely explanation is that the set of strategies that brought initial success

are not the onesnot powerful enoughto take us to higher levels. In these cases,

we would expect the best learning organizations to investigate, learn, experiment,

and develop better solutions. This takes time. (Incidentally, with the right kind of

intelligent accountability we would know whether organizations are engaged in

quality problem-solving processes even if their short-term outcomes are not showing

increases.)

While this new adaptive work is going on we would not expect achievement scores

to rise in a linear fashion, and any external assessment scheme that demanded

adequate yearly progress would be barking up the wrong tree.

Cyclical energizing is a powerful new idea. While we dont yet have the precision

to know what cyclical energizing looks like in detail, the concept needs to be a

fundamental element of our sustainability strategizing.

The long lever of leadership

First, if a system is to be mobilized in the direction of sustainability, leadership at all

levels must be the primary engine. Second, the main work of leaders is to help put

into place the previous seven elementsall seven simultaneously feeding on each

other. To do this we need a system laced with leaders who are trained to think in

bigger terms and to act in ways that affect larger parts of the system as a wholethe

new theoreticians. In Leadership and Sustainability (Fullan, 2005) sets out many

examples of the kind of leadership development we need at the school, district and

system levels to produce more of the leadership we are talking about here.

Implications

The purpose of this paper is not to provide just an analysis of the problem. It is to

challenge us to develop strategies, training, experiences and day-to-day actions

within the culture of the organization whose intent would be to generate more and

more leaders who could think and act with the bigger picture in mind thereby

changing the context within which people work in order to go beyond individual and

team learning to organizational learning and system change. This, it seems to me, is

123

122

J Educ Change (2006) 7:113122

the key to better organizational performance and to enhancing the conditions for

sustainability.

The new requirements I am suggesting also help us transcend the ceiling or

plateauing effects of what I have called phase one large scale reform. Phase one

success involves increasing student achievement, such as raising the bar and closing

the gap in literacy. In even the most successful cases such as Englands, there is a

leveling off or plateauing effect, where a certain new level is reached, but then settles

in. Phase two involves going deeper which means changing the very conditions,

contexts and cultures at all levels of the system. It is, in other words, the future

agenda of large scale, sustainable educational change.

References

Association of Teachers and Lecturers, National Union of Teachers, and Professional Association of

Teachers (2004). Reclaiming assessment for teaching and learning. London: Authors.

Barber, M. (2004). The participating citizen: A biography of Alfred Schutz. New York: State University of New York Press.

Bentley T., & Wilsdon J. (Eds) (2003). The adaptive state: Strategies for personalizing the public

realm. London: Demos.

Black, P. Harrison, C., Lee, C., Marshall, B., & Wiliam, D. (2003). Assessment for learning. Philadelphia: Open University Press.

Deming, W. E. (1986). Out of the crisis. Cambridge, MA.: MIT Press.

Fullan, M. (2003a). Change forces with a vengeance. London: Routledge Falmer.

Fullan, M. (2003b). The moral imperative of school leadership. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Fullan, M. (2005). Leadership and sustainability. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Gladwell, M. (2000). Tipping point. Boston: Little Brown.

Hargreaves, A., & Fink, D. (2006). Sustainable leadership. San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

Hargreaves, D. (2003). Education epidemic. London: Demos.

Heifetz, R. (2003). Adaptive work. In T. Bentley J. Wilsdon (Eds.), The adaptive state (pp. 6878).

London: Demos.

Heifetz, R., & Linsky, M. (2002). Leadership on the line. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Kegan, R., & Lahey, L. (2001). How the way we talk can change the way we work. San Francisco:

Jossey Bass.

Loehr, J., & Schwartz, T. (2003). The power of full engagement. New York: Free Press.

Miliband, D. (2004). Personalized Learning: Building New Relationships With Schools. Speech

presented to the North of England Education Conference. Belfast, Northern Ireland, 8th January 2004.

Perkins, D. (2003). King Arthurs roundtable. New York: Wiley.

Pfeffer, J., & Sutton, R. (2000). The knowing-doing gap. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Senge, P. (1990). The fifth discipline: the art and practice of the learning organization. New York:

Doubleday.

123

You might also like

- The Future of Educational Change: System Thinkers in ActionDocument10 pagesThe Future of Educational Change: System Thinkers in ActionDaniela VilcaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 11 ArticleDocument15 pagesChapter 11 ArticlemohamedNo ratings yet

- Learning Organization and Change ManagementDocument20 pagesLearning Organization and Change Managementfikru terfaNo ratings yet

- Learning 0rganizationDocument15 pagesLearning 0rganizationsapit90No ratings yet

- Group7 ManagingAssig March20thDocument14 pagesGroup7 ManagingAssig March20thNasreen AshkananiNo ratings yet

- The Principal: Leadership For A Global SocietyDocument32 pagesThe Principal: Leadership For A Global SocietymualtukNo ratings yet

- Leadership Mini ProjectDocument4 pagesLeadership Mini Projectmayank bhutiaNo ratings yet

- A Study On Collaborating Learning Organization in Waleed Company 6-2-2018Document19 pagesA Study On Collaborating Learning Organization in Waleed Company 6-2-2018Sam SameeraNo ratings yet

- Liderazgo Transformacional en La Gestión Institucional de Institutos Tecnológicos Superiores de La Provincia de Los Ríos, Año 2015Document8 pagesLiderazgo Transformacional en La Gestión Institucional de Institutos Tecnológicos Superiores de La Provincia de Los Ríos, Año 2015inventionjournalsNo ratings yet

- Building Strategy From The Middle: Reconceptualizing Strategy ProcessDocument18 pagesBuilding Strategy From The Middle: Reconceptualizing Strategy ProcessItaliaNo ratings yet

- Chadwick e Raver (2012)Document30 pagesChadwick e Raver (2012)Vinícius RennóNo ratings yet

- The Rainmaker Effect: Contradictions of the Learning OrganizationFrom EverandThe Rainmaker Effect: Contradictions of the Learning OrganizationNo ratings yet

- ثلاث نظريات للتعايم التنطيميDocument645 pagesثلاث نظريات للتعايم التنطيميqoseNo ratings yet

- Feldman Senges Fifth DisciplineDocument5 pagesFeldman Senges Fifth Disciplinebalaji.peelaNo ratings yet

- JM Docgen No (Mar8)Document6 pagesJM Docgen No (Mar8)Ulquiorra CiferNo ratings yet

- Getenet ArtiDocument4 pagesGetenet ArtihakiNo ratings yet

- Organizational Change and Development Chapter 12Document27 pagesOrganizational Change and Development Chapter 12Basavaraj PatilNo ratings yet

- Learning LeadershipDocument10 pagesLearning LeadershipMuhammad IqbalNo ratings yet

- Researchpaper - Impact of Knowledge Management Practices On Organizational Performance An Evidence From Pakistan PDFDocument6 pagesResearchpaper - Impact of Knowledge Management Practices On Organizational Performance An Evidence From Pakistan PDFAyesha AmanNo ratings yet

- ID 261 Mjoen K, Lyso IDocument9 pagesID 261 Mjoen K, Lyso IMoh SaadNo ratings yet

- MLC AssignmentDocument9 pagesMLC AssignmentRabi AdhikaryNo ratings yet

- Summative Assessment Literature ReviewDocument22 pagesSummative Assessment Literature Reviewdoaa shafieNo ratings yet

- School OrganizationDocument34 pagesSchool OrganizationirdawatyNo ratings yet

- Analysis and Evaluation of Organizational Change ApproachesDocument5 pagesAnalysis and Evaluation of Organizational Change ApproachesSITINo ratings yet

- Changing Facets of ODDocument9 pagesChanging Facets of ODpriyanka0809No ratings yet

- Senge's Fifth Descipline PDFDocument5 pagesSenge's Fifth Descipline PDFrachmatiaynNo ratings yet

- Organizational Commitment: Chapter-IIIDocument35 pagesOrganizational Commitment: Chapter-IIISanket Shivansh SrivastavaNo ratings yet

- A Case Study of A University Leadership SeminarDocument14 pagesA Case Study of A University Leadership Seminarmazen rabaaNo ratings yet

- Organizational Change and DevelopmentDocument42 pagesOrganizational Change and DevelopmentMukesh Manwani100% (1)

- Peter Senge and The Learning OrganizationDocument15 pagesPeter Senge and The Learning OrganizationMarc RomeroNo ratings yet

- Systemic Thinking Education LeadershipDocument9 pagesSystemic Thinking Education Leadershipmariordonezm_3853771No ratings yet

- LWhat - Learning OrganizationsDocument24 pagesLWhat - Learning OrganizationsNu RulNo ratings yet

- Handbook for Strategic HR - Section 4: Thinking Systematically and StrategicallyFrom EverandHandbook for Strategic HR - Section 4: Thinking Systematically and StrategicallyNo ratings yet

- Review of Related Literature and StudiesDocument30 pagesReview of Related Literature and StudiesMikha DacayananNo ratings yet

- BAGAADocument10 pagesBAGAAlemma4aNo ratings yet

- Arely Flores Research Paper RevisedDocument10 pagesArely Flores Research Paper Revisedapi-676549138No ratings yet

- The “New” Epidemic– Grading Practices: A Systematic Review of America’S Grading PolicyFrom EverandThe “New” Epidemic– Grading Practices: A Systematic Review of America’S Grading PolicyNo ratings yet

- Fullan 8 Forces AnalysisDocument6 pagesFullan 8 Forces Analysisranjitd07No ratings yet

- Change ManagementDocument5 pagesChange ManagementJenelle OngNo ratings yet

- Why Use Social Critical and Political Theories in Educational LeadershipDocument18 pagesWhy Use Social Critical and Political Theories in Educational LeadershipPedro FerreiraNo ratings yet

- Organizational Behavior: A Study On Managers, Employees, and TeamsDocument11 pagesOrganizational Behavior: A Study On Managers, Employees, and Teamsseblewongel WondesenNo ratings yet

- Van Oosten (2006) PDFDocument11 pagesVan Oosten (2006) PDFbeiboxNo ratings yet

- Summary Book Managing Organizational Change PDFDocument20 pagesSummary Book Managing Organizational Change PDFBurak Kale0% (1)

- 02 Book Review - Change Management by V Nilakant and S RamnarayanDocument4 pages02 Book Review - Change Management by V Nilakant and S Ramnarayananeetamadhok9690No ratings yet

- Use of A Rule Tool in Data Analysis Decision Making-with-cover-page-V2Document11 pagesUse of A Rule Tool in Data Analysis Decision Making-with-cover-page-V2Mian Asad MajeedNo ratings yet

- Yielding Systems Thinking in School LeadershipDocument2 pagesYielding Systems Thinking in School LeadershipnixoneNo ratings yet

- Creating A Learning OrganizationDocument15 pagesCreating A Learning OrganizationZahraJanelleNo ratings yet

- Senge's Fifth DesciplineDocument5 pagesSenge's Fifth DesciplineIchda QomariahNo ratings yet

- Abstract: The Purpose of This Paper Is To Present Findings On Educational Change and EffectiveDocument6 pagesAbstract: The Purpose of This Paper Is To Present Findings On Educational Change and EffectivePhuong NgoNo ratings yet

- Thesis On Organizational BehaviorDocument7 pagesThesis On Organizational Behaviorwavelid0f0h2100% (2)

- Ginter Chapters 1 4Document49 pagesGinter Chapters 1 4laghribNo ratings yet

- OD AssignmentDocument6 pagesOD AssignmentNarro NavarroNo ratings yet

- Fifth Discipline SummaryDocument7 pagesFifth Discipline Summarysyedhabeeb_12766100% (2)

- The Collegial Leadership Model: Six Basic Elements for Agile Organisational DevelopmentFrom EverandThe Collegial Leadership Model: Six Basic Elements for Agile Organisational DevelopmentNo ratings yet

- Situational Outlook Questionairre Isaksen 2007Document14 pagesSituational Outlook Questionairre Isaksen 2007Azim MohammedNo ratings yet

- Change Management ScopeDocument1 pageChange Management ScopeHabib GulNo ratings yet

- Leadership and Change Management Research PaperDocument4 pagesLeadership and Change Management Research PapertmiykcaodNo ratings yet

- Holacracy 2022Document16 pagesHolacracy 2022keis.alschihapieNo ratings yet

- IntroductionDocument10 pagesIntroductionyou jiaxiNo ratings yet

- Transport System in Living ThingsDocument40 pagesTransport System in Living ThingsHarijani SoekarNo ratings yet

- Sjögren's SyndromeDocument18 pagesSjögren's Syndromezakaria dbanNo ratings yet

- Pedia Edited23 PDFDocument12 pagesPedia Edited23 PDFAnnJelicaAbonNo ratings yet

- The Setting SunDocument61 pagesThe Setting Sunmarina1984100% (7)

- Case Study GingerDocument2 pagesCase Study Gingersohagdas0% (1)

- 1219201571137027Document5 pages1219201571137027Nishant SinghNo ratings yet

- Brief For Community Housing ProjectDocument5 pagesBrief For Community Housing ProjectPatric LimNo ratings yet

- DeathoftheegoDocument123 pagesDeathoftheegoVictor LadefogedNo ratings yet

- Periodic Table & PeriodicityDocument22 pagesPeriodic Table & PeriodicityMike hunkNo ratings yet

- SBFpart 2Document12 pagesSBFpart 2Asadulla KhanNo ratings yet

- Ebook Essential Surgery Problems Diagnosis and Management 6E Feb 19 2020 - 0702076317 - Elsevier PDF Full Chapter PDFDocument68 pagesEbook Essential Surgery Problems Diagnosis and Management 6E Feb 19 2020 - 0702076317 - Elsevier PDF Full Chapter PDFmargarita.britt326100% (22)

- Methods in Enzymology - Recombinant DNADocument565 pagesMethods in Enzymology - Recombinant DNALathifa Aisyah AnisNo ratings yet

- 08-20-2013 EditionDocument32 pages08-20-2013 EditionSan Mateo Daily JournalNo ratings yet

- Mudbound: Virgil Williams and Dee ReesDocument125 pagesMudbound: Virgil Williams and Dee Reesmohan kumarNo ratings yet

- Molecular Biology - WikipediaDocument9 pagesMolecular Biology - WikipediaLizbethNo ratings yet

- Media Planning Is Generally The Task of A Media Agency and Entails Finding The Most Appropriate Media Platforms For A ClientDocument11 pagesMedia Planning Is Generally The Task of A Media Agency and Entails Finding The Most Appropriate Media Platforms For A ClientDaxesh Kumar BarotNo ratings yet

- All-India rWnMYexDocument89 pagesAll-India rWnMYexketan kanameNo ratings yet

- English Solution2 - Class 10 EnglishDocument34 pagesEnglish Solution2 - Class 10 EnglishTaqi ShahNo ratings yet

- Tiananmen1989(六四事件)Document55 pagesTiananmen1989(六四事件)qianzhonghua100% (3)

- R. K. NarayanDocument9 pagesR. K. NarayanCutypie Dipali SinghNo ratings yet

- Post Employee Benefit Psak 24 (Guide)Document21 pagesPost Employee Benefit Psak 24 (Guide)AlvianNo ratings yet

- Grill Restaurant Business Plan TemplateDocument11 pagesGrill Restaurant Business Plan TemplateSemira SimonNo ratings yet

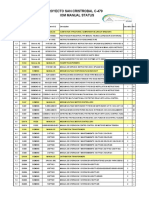

- Proyecto San Cristrobal C-479 Iom Manual StatusDocument18 pagesProyecto San Cristrobal C-479 Iom Manual StatusAllen Marcelo Ballesteros LópezNo ratings yet

- Systems Analysis and Design 11th Edition Tilley Test BankDocument15 pagesSystems Analysis and Design 11th Edition Tilley Test Banksusanschroederoqdrkxtafn100% (15)

- Lae 3333 2 Week Lesson PlanDocument37 pagesLae 3333 2 Week Lesson Planapi-242598382No ratings yet

- Degree Program Cheongju UniversityDocument10 pagesDegree Program Cheongju University심AvanNo ratings yet

- Rock Type Identification Flow Chart: Sedimentary SedimentaryDocument8 pagesRock Type Identification Flow Chart: Sedimentary Sedimentarymeletiou stamatiosNo ratings yet

- 5010XXXXXX9947 04483b98 05may2019 TO 04jun2019 054108434Document1 page5010XXXXXX9947 04483b98 05may2019 TO 04jun2019 054108434srithika reddy seelamNo ratings yet

- Global Slump: The Economics and Politics of Crisis and Resistance by David McNally 2011Document249 pagesGlobal Slump: The Economics and Politics of Crisis and Resistance by David McNally 2011Demokratize100% (5)

- Lifetime Prediction of Fiber Optic Cable MaterialsDocument10 pagesLifetime Prediction of Fiber Optic Cable Materialsabinadi123No ratings yet