Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Saville - A Comment On Professor Rostow S British Economy of The 19th Century

Saville - A Comment On Professor Rostow S British Economy of The 19th Century

Uploaded by

SpasiukOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Saville - A Comment On Professor Rostow S British Economy of The 19th Century

Saville - A Comment On Professor Rostow S British Economy of The 19th Century

Uploaded by

SpasiukCopyright:

Available Formats

The Past and Present Society

A Comment on Professor Rostow's British Economy of the 19th Century

Author(s): John Saville

Reviewed work(s):

Source: Past & Present, No. 6 (Nov., 1954), pp. 66-84

Published by: Oxford University Press on behalf of The Past and Present Society

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/649815 .

Accessed: 22/12/2011 12:13

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Oxford University Press and The Past and Present Society are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve

and extend access to Past & Present.

http://www.jstor.org

66

PAST AND PRESENT

A Comment on Professor Rostow's British

Economy of the 19th Century

ECONOMICHISTORIANSIN BRITAINHAVE,UNTIL RECENTYEARS,USUALLY

employed an empirical approach to the study of economic development. Most of the theoretical advances that have been made are

the work of scholars of other nationalities.1 It was the considerable

merit of Professor W. W. Rostow, beginning with his well-known

article in the Economic History Review for I938, and carried a stage

further by the publication of the British Economy of the Igth Century

in I948,2 that he made the attempt to rewrite the economic history

of 19th-century Britain in terms of a sustained dynamic analysis.

His book was warmly welcomed as an exciting piece of research which

provided a suggestive interpretation of old data. Its main thesis was

a simple one, based upon the " streamlined parable 5T3 that was set

out in its opening pages, the conclusions of which were " that the

main trends in the British economy, over the period I790-I914, are

best understood in terms of the shifting balance between productive

and unproductive outlays; and among types of productive outlays

with differing yields and differing periods of gestation."4

Professor Rostow's analysis is based upon a functional relationship

between the type of investment on the one hand, and the movement

of prices, the terms of trade and real wages, on the other. When the

character of investment is productive, which broadly means that

domestic investment yields its results in the short run, prices

fall, real wages rise and the terms of trade shift favourably to Britain.

Conversely, when investment outlays are unproductive (as in wars),

or when they are channelled into projects which yield their economic

results only over a long period, as with British capital investment in

railway construction in a " new " country, prices rise, real wages fall,

and the terms of trade move against Britain. Using these concepts,

Professor Rostow divided the I9th century after I8i55 into four

main periods: the first, from I815 to I847, years of intensive home

investment; the second, from I848 to I873, when investment outlays

were either in wars or long term in their economic effects; the

third, from I873 to I898, when investment was once again directed

towards home resources; and finally, from I898 to I914 when capital

was invested abroad rather than at home. There are then, on this

analysis, two periods when capital investment was mainly concentrated

at home, and two periods when investment outlays were largely

BRITISH ECONOMY OF THE I9TH

CENTURY

67

unproductive or with a long gestation period. As a result of the

predominantly domestic character of investment, the years between

I815 to I847, and I873 to I898, showed a falling price trend, rising

real wages and favourable terms of trade. By contrast, the third

quarter of the century (I848-73) and the decade and a half before

I914

(I898-I914) exhibited the opposite trends of rising prices,

falling real wages and unfavourable terms of trade.

The merit, and it is considerable, of this approach is that it concentrates attention upon capital accumulation and investment as

among the crucial determinants of a capitalist economy. Professor

Rostow's work has undoubtedly provided an additional stimulus to

the study of real phenomena (in the Keynesian sense of the term).

At the same time there is some doubt about the relevance to i9th

century economic development of the elegant model that he has

constructed. The usefulness of any particular theory must be

judged on two counts: first, the internal consistency of the theoretical

model and second, the validity of its theoretical assumptions in

It is with certain apparent

relation to the established facts.

divergences from the established facts that this commentary upon

Professor Rostow's analysis will begin.

To consider first Professor Rostow's periodisation of English

economic history in the i9th century. He uses the traditional

textbook division into periods whose boundaries are set by long term

price changes. He accepts the picture of falling prices to I847 and,

in his own words, the " famous price level increase of the third

quarter" as reflecting, in both periods, different phases of the

industrialising economy. The change from one period to another

he puts at I847. Professor Rostow, following J. M. Keynes, suggests

more sophisticated reasons for these price movements than were

common before the Treatise on Money, and he is concerned primarily

with investment and production, and with prices only as a consequence

of changes in the character of investment outlays. It is, however,

worth noting that the movement of prices from 1815 to I873 is not as

simple and straightforward as has been generally accepted. An

examination of the wholesale price index for the middle decades of the

century shows a rise between I844 and I847, a fall to I849, no

appreciable change to 1852 followed by a very steep increase to I854.

Then, from the middle I85os to the end of the i86os wholesale prices

remain on a fairly steady level, followed by a sharp rise between

I870 and I873, the steepness of the increase being less than

that of the early I85os.6 Some detailed price data for the third

quarter, set out by Professor Rostow himself in a recent article,

68

PAST AND PRESENT

show that out of eight important commodities only two - cotton

and wool - had substantial price increases while another three sugar, timber and wheat - showed absolute declines in price.7 In

general, the picture is more complicated than is usually appreciated.

What is very marked is the way in which prices are jacked-up to a

new high level with the sharp upward movement of the early I85os,

but this phenomenon is not the same as a rising price trend between

I847 and I873; nor can the break in the trend be put just before the

half century. Some years ago A. F. Burns and W. C. Mitchell made

a relevant comment in this connection.

"The long waves (of prices J.S.) are clearest in Britain, yet one

who did not alreadyknow these waves in advance might conclude

that the trend of prices was not falling from 1823-I84I or rising

during I853-I87I."8

There is some reason therefore to question the traditional acceptance of the price movements for the half century after I815;

but Professor Rostow was concerned with prices only as the

product of other factors. More central to his argument are the

data for capital export. The main difference, he argued, between

the years after I8I5 and the years after I847 lay in the character

of investment in these two periods. In the first there was a

concentration upon domestic investment and an absence of what

he characterises as unproductive investment (including that with a

long gestation period), and in the second there takes place a shift

towards foreign outlays and government expenditures on wars.

We have, as our guide to the movements of British capital exports,

the calculationsthat ProfessorImlah has recentlypublished (Table i).

The Limitations of any of our existing figures on the balance of

payments and capital exports are well enough known, although it is

likely that this series prepared by Professor Imlah (which was not

available to Professor Rostow in I948) are more accurate than those

that have been used in the past. If we examine the data for net

income available for capital export for two decades on either side

of I847 we find that until the middle of the I85os there are

fluctuations around a fairly low annual average. The boom years

of I852-4 exhibit the much-discussed contrasting movement of a

decline in capital export against the backgroundof rising domestic

investment; and what apparentlydoes not occur is any shift towards

foreign outlays until after I855. At that date the change appearsto

be very marked, but on Professor Imlah's figures, it is difficult to

suggest a crucial turning point in the characterof investment at the

end of the I84os.

BRITISH ECONOMY OF THE I9TH CENTURY

69

TABLE I

NET INCOMEAVAILABLE

FOR FOREIGNINVESTMENT

Five Yearly Averages.

I831-35

I836-40

I841-45

I846-50

I851-55

I856-60

I86i-65

I866-70

I871-75

-.

.

..

...

...

...

...

.....

7.30

2.62

6.96

6.i8

7.62

24.82

23.00

39-3

73.96

Million.

184I

I842

I843

I844

I845

I846

I847

1848

I849

I850

Annual Figures.

..

.

...

...

...

...

...

...

.,

...

2.7

I.0

I0.3

II.2

9.6

9.6

0-5

2.7

6.5

ii.6

...

I851

...

852

...

I853

...

I854

...

1855

...

I856

I857 ..

...

I858

..

I859

...

i86o

I0.4

7*9

3.4

4.6

II.8

20.7

26.0

20.9

34.2

22.3

(From A. H. Imlah, "British Balance of Payments and Export of

Capital I816-I913,"

(1952).

Economic History Review, 2nd, Ser. V, No.

If we turn next to examine the movement of real wages, so

intimately connected in Professor Rostow's model with the particular

type of investment the economy is experiencing, we are involved in

one of the most controversial questions of the history of the years

before I85o. Since real wages are at the centre of Professor

Rostow's theoretical analysis, their direction after 1815 is a matter of

considerable importance. It may be remarked in passing that

considering the crucial significanceof the movement of real wages in

Professor Rostow's model (" The focus is, rather, the complex of

forces affecting the course of real wages "9) it is somewhat surprising

to find no analysis at all of the characteristicsof the labour market

in Britain during the i9th century. It is investment, its scale and

character,and the movements of interest rates, prices and the terms of

trade that affect the fluctuations in, and the direction of, real wages,10

and it would appearthat the size, the compositionand the institutional

characteristics of the labour market are of little importance. But

to return to the half century after i8I5. What may perhaps be

called the classical view was that a deteriorationin living standards

occurred during the three decades after the end of the Napoleonic

Wars (" the legend that everything was getting worse for the working

man, down to some unspecified date between the drafting of the

People's Charter and the Great Exhibition "1). This view has

been opposed by J. H. Clapham,from whom the quotationwas taken,

Professor Ashton and others.12 Certainly the rise in real wages is

70

PAST

AND

PRESENT

documented for artisans and skilled workers although no one can

be satisfied with the cost of living indices (an essential part of the

evidence) whose limitations have come to be increasingly recognised.

The central problem, however, to which almost no attention has been

paid, is to determine the social composition of the proletarian masses

and to arrive at some estimate of the numbers of skilled and unskilled

workers, both in the factory and, even more important, in the unrevolutionised small master industries. The important preliminary

analysis by Dr. Hobsbawm suggests that " the favoured strata of

the working population were much less numerous than the rest,"13

and if those groups for whom there is reasonable evidence of an

improvement in living standards are found to be only twenty or

thirty per cent of the total proletarian population, then the more

optimistic views of recent years will need to be seriously modified.

There would seem to be no incontrovertible statistical basis for the

statement that " despite a number of difficult years, real wages

rose for a rapidly expanding population."14 Mr. Matthews has

found no increase of any significance in living standards during

the I83os,15 and contemporary evidence of a non-statistical nature

is also against this view.

There are two other aspects of the economic history of the years

after I815 on which the evidence to some extent conflicts with the

interpretation suggested by Professor Rostow. The first concerns

the terms of trade, which, in his analysis of the years after 1815,

occupy a rather ambiguous position. In his brief summary of the

period I815-47 (pp. I7-I9) Professor Rostow uses the phrase " the

terms of trade " without indicating whether he is referring to the

gross or the net barter terms of trade. Some evidence suggests the

former, but then on p. 25, when discussing the Great Depression

he refers to the " phenomena . . . essentially the same as those

which dominated the period from I815 to the end of the forties,"

and includes a specific reference to the " favourable shift in the terms

of trade." Now both the gross and the net barter terms of trade

moved favourably to Britain after I880; but almost the opposite

One of the striking differences of the postoccurred before I850.

I815 years compared with the period of the Great Depression is the

marked and notable deterioration of the net barter terms of trade.

This decline of British export prices relative to import prices has long

been recognised as a most prominent feature of the first half of the

19th century, and is usually explained in terms of the existence of

one country (Britain) rapidly industrialising herself in a world which

remained predominantly agrarian.16 The primary production of

BRITISH ECONOMY OF THE I9TH

CENTURY

7I

those countries trading with Britain - with the very important

exception of raw cotton from America - was increasing at a much

slower rate than industrial production in Britain.'7 The causes of

this particular Britain-World relationship were, in the main, the

opposite of those which produced the favourable terms of trade for

One was the relatively

Britain in the years of the Great Depression.

slow improvement, before the railway age of the I84os, of transport

facilities; a second was the high degree of protectionism before I840;

and a third, perhaps of crucial importance, was the continued

existence of feudal and semi-feudal relationships over most of the

European countryside. While the gross barter terms of trade did

not show the same sharply declining trend as did the net barter

terms of trade, it is the decline of the latter which it is difficult to

reconcile with the assumptions from which Professor Rostow argues.

Nor can his simple theoretical model explain why the net terms of

trade begin to move in Britain's favour after I86o and again turn

against her during the ten years which followed I873. The economic

relationships between Britain and the world economy were more

complex than the British Economy is prepared to allow.

One last point on the decades before the Great Depression. It is

far from the intention of this essay to suggest an alternative periodisation of 19th-century development to that put forward by

Professor Rostow. It is, however doubtful whether, on the evidence

of prices and more especially of the data for capital export, we can

accept I847 as a meaningful dividing line between two supposedly

different economic periods; and the statistical series we have of the

movements of production suggest a further reason why we ought to

look once again at our traditionally accepted divisions. Professor

Rostow's analysis was not dependent for its confirmation upon

production movements; but if we analyse the movements of

production, some interesting conclusions emerge which conflict with

his generalisations concerning the dividing year of I847. Professor

Rostow used Hoffman's well-known index of industrial production,

first published in 1934; and for the purposes of the present note, the

annual average rate of production has been calculated from Hoffman's

indices on a five-yearly basis. The results are set out in Table II.

Taking first total industrial production, it will be seen that the

decades immediately after I8I5 show the most rapid development

of domestic resources in the whole of the I9th century.18 From I815

to I830 the annual average rate of increase of total production was

3.5/o; between I830 and I855 it was 3.6%; in the succeeding twenty

years to I875 it fell to 2.8%. Individual years showed wide

PAST AND PRESENT

72

fluctuations, but the significant fact is that for the forty years after

1815 the British economy had a remarkablysteady and high average

annual increase in total production. The data for producer's goods

are even more striking,in that they bring into focus the years between

1830 and 1855 as a period of very rapid economic development.

The annual average rate of growth for capital goods was 3.6%

between 1815 and 1830, 5.1% for the years between 1830 and 1855,

and 3.5% from i855 to 1875. There are no doubt a number of

qualifications which statisticians would wish to make in respect or

Hoffman's data and the series has been revised by Hoffman himself19

since its first publication in 1934, but the index was broadly accepted

by Professor Rostow and used by him.20 On the basis of these

productionfigures, there is no breakaround 1847 but rather a marked

slackening in the rate of growth of both capital and total goods

production after 1855.

TABLE II

ANNUAL AVERAGEPERCENTAGERATE OF CHANGE

I815-20

1820-25

Total

Producer's

Production Goods

...

2.4 ... 2.1

...

4.4 ... 6.2

... 3.7 ... 2.5

Total Producer's

Production

Goods

1845-50

...

3.5

...

6.6

1850-55

...

4.1

...

5.1

I855-60

...

2.4

...

3.1

1830-35 ...

1835-40 ...

3.9

3.6

...

...

5.1

5.5

1860-65 ...

I865-70 ...

2.3

3.7

...

...

4.6

3.2

...

3.0

...

3.3

1870-75

...

2.8

...

3.0

1825-30

1840-45

(The rates are averaged as between five-year intervals centered

on the indicated year. This is the method used by ProfessorRostow.

See Table I (p. 8), British Economy of the I9th Century.

are from Hoffman: Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, 1934).

The data

II

When we turn to the last quarterof the 19th century the statistical

materialon which generalisationscan be made, while still imperfect,

are nevertheless much more reliable than those discussed above;

and, it must be added, a number of important series have been

published since Professor Rostow wrote in 1948. For Professor

Rostow the Great Depression, which he put between the years

1873 and 1898, was characterised by a shift from domestic to

BRITISH ECONOMY OF THE I9TH CENTURY

73

foreign investment: " the centralcausal force in the Great Depression

was the relative cessation of foreign lending."21 This shift in the

direction of capital outlays brought with it " phenomena . . .

essentially the same as those which dominated the period from

I815 to the end of the forties: a favourable shift in the terms of

trade; a fall in interest rates and commodity prices; a maintained

rise in real wages."22

The facts of capital export and domestic investment, on which so

much of the argument must rest, can be easily stated.23 In general,

the twenty years from 1873 exhibit the familiarscissors movement of

home and foreign investmenr. The peak year for capitalexport in the

third quarter of the century came in I872, with the two following

years showing declines but still maintaininga high rate. Then, from

I875 the decline in capital export became very marked,the low point

being reached in I877 (a year when there was still, according to

Imlah's series, and contraryto earlier calculations,a small net surplus

of income available for foreign investment). Net domestic investment, excluding housing, declined sharply from its peak in I873 to

I875, recovered in I876 and I877 and then fell to a low point in I879.

Investment in housing, to which, it must be pointed out, Professor

Rostow allows an inadequateplace in total investment outlays,24rose

steadily to a peak in I877 and then declined slowly to its lowest

point in the middle of the I88os. The investment data of the

I87os, to sum up, confirm the turn towards domestic investment and

away from foreign outlays which Professor Rostow emphasises is the

central feature of the Great Depression. It is the next decade in

which the facts do not appearto support his thesis.

The notable feature of domestic investment in the i88os is the low

level of new capital expenditure on housing. Total net domestic

investment (including housing) has two peaks - one in I882 and the

second in I889 - and both were smaller in absolute terms and as

proportionsof the National Income than the peaks of I873 and I877.

Foreign investment on the other hand, increased jerkily from the

low point of I877 (with decreases on immediately preceeding years

in I88o, I882, I883, I885 and I889) to a peak in I890, after which it

once again fell away. Total investment (domestic and foreign) was

roughly the same in terms of its proportion of the National Income

in both decades; but net home investment in the i88os was lower

absolutely and relatively to National Income than in the I870s,

and foreign investment, absolutely and as a proportionof the National

Income, was higher than in the I87os.

This was the crucial difference

betweenthe two decades. It means that the depression of the I88os

74

PAST AND PRESENT

was more pronounced in home investment than in foreign investment.

There was no shift to domestic investment in the i88os; for the

four years 1884-7 net home investment (in terms of the National

Income) was lower than in any year of the I87os except 1879. These

middle years of the i88os are to be compared, in the matter of the

low volume of home investment, with the early years of the iS90S;

the new factor in the I89os is the steadily declining absolute volume

of foreign investment.

If there is no evidence of a relative shift in investment outlays

towards the home market in the i88os and the early I89os, neither

is there any reason to date the beginning of a new period in 1898.

Rostow argues that the British economy, at the end of the I89os " was

on the eve of a new secular phase,"2 when the characteristics of the

third quarter of the century - a shift towards foreign outlays with the

be repeated. Once

accompanying effects upon the economy-would

again the facts would appear not to support these generalisations.

From I895 to I904, total net domestic investment, including housing,

was never less than seven per cent of the National Income and in

In the same years foreign investment

I899/1900 it was over Io%.

was phenomenally low, and it remained at a low level for a longer

period than at any time since I870. If the character of investment is

a determining factor in the shape of an economy, as Professor

Rostow argues, the home boom of 1895-1904, which was the result

of a high level of domestic outlays, cannot be included within the

same trend period as the years which followed I905, when home

investment declined sharply as capital exports rose to their highest

absolute and relative level for the whole century.

Hoffman's production data confirm the slowing down in the

general rate of growth of the economy after the I87os; and for

comparison with earlier decades, see Table II.

TABLE

III

ANNUAL AVERAGEPERCENTAGERATE OF CHANGE

I870-75

I875-80

I880-85

I885-90

Total

Producer's

Produzction Goods

...

2.8

...

3.0

i.i

...

...

3.1i

...

...

1.9

I.3

...

...

2.6

2.3

I890-95

895-I900

I900-05

I905-IO

Total

Producer's

Goods

Production

0.8

...

0.8

...

2.3

3.1

...

2.0

I.3

...

...

I

0.8

(From Hoffman: Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, I934).

BRITISH ECONOMYOF THE I9TH CENTURY

75

We must conclude from an analysis of the character of investment that the years from 1873 to 1894 do not appear to agree with

the thesis put forward by Professor Rostow. Whatever else the

Great Depression was, and whatever other characteristics it possessed,

it was not a period of economic development during which there was

a shift within investment outlays to a more intensive exploitation

of home resources. It is, on the contrary the apparent stagnation of

domestic investment opportunities during most of the i88os and the

early I89os that requires an explanation.

III

In concentrating upon the character of investment rather than its

volume, Professor Rostow is assuming that throughout the century

the volume of investment was sufficient in each main trend period to

maintain roughly the same level of employment throughout the

economy. He is explicit about this assumption, which is of crucial

importance in his argument and which has not received from his

commentators the attention it deserves. In his own words,

" Significant differences in the level of employment would affect the

validity of an analysis which put primary emphasis on the character

of investment rather than on its volume. No significant distinctions

on existing evidence are found," '; and to make his point he examined

the unemployment data from 185o and concluded that there was no

evidence " to justify the view that the Great Depression period was

marked by significantly higher unemployment than the average

from the mid-century to the outbreak of war in 1914."27 There

are two comments worth making on these statements. The first is

that Professor Rostow makes no serious attempt to assess the worth

of these unemployment data; a rather surprising omission considering

how much of his analytical model depends upon the assumption

that changes in the volume of investment could be ignored for the

Both the usefulness of the series and the inwhole century to I9I4.8

can

be

that

fairly placed upon them have been discussed

terpretations

elsewhere2' but it is perhaps worthwhile to make one general point

here. The unemployment series are for skilled workers and have

been compiled in the main from the records of the skilled trade

unions. How relevant the unemployment data of skilled workers are

for an assessment of the general level of employment is a question

which demands an answer; and the further back in time one goes

the less obvious is the usefulness of this particular yardstick. In i85o

the factory was not the representative unit of industrial organisation

and the skilled workers in number were no more than a substantial

minority of the labour force. This is not to deny the usefulness of

76

PAST AND PRESENT

this unemployment series but it must be properly handled; and in

the small master economy of the i85os its relevance is less, perhaps

a good deal less, than for the decades immediately preceeding I914.

There is a second general point to be made in connection with Professor Rostow's use of the unemployment figures, on the legitimate

assumption that the series is of some use in estimating the level of

employment. It is a criticism which has already been argued by

Professor D. H. Robertson. To prove the point that the level of

employment was approximatelythe same over the whole period from

I850 to the first World war, ProfessorRostow summarisedthe average

unemployment figures for I855-73, I874-I900

and I90I-I3;

and the

averages came out at 4.8%, 4.9% and 4.5%o. The immediate

point that strikes the reader is to ask why these particular periods

were chosen when they do not correspond with the trend periods

which Rostow insists upon throughout his book. Professor

Robertson, who made this point indirectly, went on to show that if the

crude averages for I851-73,

I874-95 and I896-I914

were worked

out the unemploymentpercentageswere respectively4.6%, 5.4 % and

4.00o. " I cannot help thinking " concluded Professor Robertson,

"there is some justification for the impression that for a quartercentury jobs were less secure than they had been or were about to

become."30

There is reason, therefore, to doubt the validity of the assumption

that lays an emphasis upon the character of investment to the

exclusion of its volume. No one will deny the analyticalusefulness of

an approachwhich directs attention to the type of investment outlet

to which the resources of an economy are being directed, but to

ignore fluctuations in the total volume of capital invested in any one

year or period is to eliminate from an historical analysis much of the

central processes of economic change. This failure to note the

changes in the level of capital investment is at the heart of Professor

Rostow's misreading of the Great Depression. By concentrating

upon the I87os and early I88os, in which years the phenomena which

he associateswith the whole period were clearlydiscernible,he missed

two crucial facts which make the Great Depression a period very

different from his characterisationof it. The first was that foreign

capital investment was rising throughout the i88os while domestic

investment remained fairly low; the second was that total investment

during the late I87os, most of the i88os and the first half of the i89os

was significantly lower than for the period I870-I914

considered as a

whole. The statisticians will no doubt be constantly refining and

improving the various series on the national income, prices and the

BRITISH ECONOMY OF THE I9TH CENTURY

77

like, but if Mr. Lenfant's statistics on capital formation are broadly

correct (or the calculations in Appendix I which are derived mainly

from Professor Phelps Brown and A. R. Prest31)then it is difficult

not to question the correctnessof an emphasis which stresses the type

of investment and ignores the problem of volume.

It is not only because of this concentrationupon type of investment

to the exclusion of other crucial problems connected with capital

accumulation that Professor Rostow must be accused of a simpliste

interpretation of 19th-century economic development. The

economic historian must ask whether it is legitimate to exclude from

a theoretical model the relationship between institutional and

economic factors in the development of a national economy. The

size and compositionof the labourforce and the generalcharacteristics

of the labour market, the organisation of industry, the character

of the home market considered from the side of demand, are all

structuralproblems whose impact upon any industrial or industrialising society is internalratherthan external. The particularstructure

:of the capital market in the I9th century is perhaps the best known

example of an institutional factor, the product of both economic and

historical forces, which exercised a marked influence upon the rate

and character of investment and therefore upon the rate of growth

of the economy as a whole. The deficiencies of the English capital

market have been much commented upon from the point of view

of the domestic capital market in the twentieth century32;but there

is no reason to believe that those deficiencies were wholly absent

during the second half of the I9th century. It is to be expected,

a priori, that the nearer one gets to I914 the more obviously the

structural defects of the domestic capital market would affect the

development of home industry. Admittedly the documentation

for such a generalisation is still far from complete; but in the one

industry, steel, where the evidence is presented in detail in the

magistral analysis of D. L. Burn, the consequences of an inadequate

rate of capital accumulation can be clearly traced upon the size and

efficiency of plants.33 There is scattered evidence elsewhere, notably

in the unpublished work of Dr. J. B. Jefferys,34that here we have an

essential clue in the analysis of the relative stagnation of British

industry before 1914. The argument may be summarised thus.

By the third quarter of the i9th century the main capital market

of the country, centered upon London, was alreadyfirmly orientated

towards the provision of the long term capital requirements of

overseas governments, foreign railways and public utilities. This

overseas demand continued strongly until I914 and the institutions

78

PAST AND PRESENT

and the traditions of the London capital market reinforced themselves

on the basis of extraordinary prosperity and profitability. There

developed a structural deficiency in respect of home investment which,

as the individualistic traditions of self-financing were no longer

capable of meeting the steadily increasing capital requirements

of industry, operated as a drag upon the whole economy from about

the i88os. It is now generally accepted that an important part of the

reasons for the lag in industrial efficiency in the decades before I914

was the relatively slow growth in size of manufacturing units. The

absence of large scale institutions catering for home industrial

investment meant that the entrepreneurs were thrown much more

upon their own financial resources than was the case in other major

industrial Powers. Certainly those resources in the case of British

industries, especially in the old basic industries, were considerable,

but the gap between individual resources and requirements must have

been growing steadily in the years before 1914. Professor Paish,

in his inaugural lecture, drew attention to the small proportion of

net domestic investment financed through the London capital market

before I914. He noted that:

"The small scale of the new issue market in home securities, and

of many of the individual issues, was no doubt the reason why the

great merchant bankers, who were responsible for the great bulk

of the issues in overseas accounts, took little interest in it, apart

from occasionally sponsoring a large issue of railway or public

utility services."3 5

But could not this formulation be put in another way? namely,

that by the time we are in the 20th century new issues were small

because of the particular way the British capital market had grown

and developed over the previous hundred years ? Mr. Dobb has

argued that the practicable alternatives that face the entrepreneur

are generally smaller than economists have generally supposed.36

The institutional structure of the capital market provided the background against which investment decisions were made; and if, as

argued above, the entrepreneurs in Britain were thrown back on their

own resources at a time when only a recourse to the open market would

have provided them with adequate capital, their overall decisions

would inevitably be coloured with elements of cautiousness and

conservatism. Vision, as well as the financial possibilities required

to translate vision into practical effect, were becoming less common

in British industry before I914, and to ignore traditional and structural

problems is to make of ones analysis a bloodless abstraction from the

historical complexities of the real world.

BRITISH ECONOMY OF THE I9TH CENTURY

79

The institutional factors noted above - the labour market, the

organisation of industry, the character of the home market - must be

left for discussion to another occasion, but mention must briefly

be made of a further serious limitation upon the usefulness of

Professor Rostow's theoretical assumptions. " After I870, Alfred

Marshall used to say, you cannot write English economic history ";

and, the late J. H. Clapham added, " he might have given an earlier

date."7 At no point indeed, in the I9th century can the British

economy be considered without reference to the rest of the (economic)

world, and as industrialisation proceeded, and as the revolution in

transport facilities completed the inter-dependence of the nations,

the relation of national economies to the world economy became

increasingly intimate. Recognition of this truism has recently been

emphatically made by Professor Rostow himself,38 and the absence

of the international background to the British economy makes much

of the argument unreal in the volume under discussion. In

particular, this failure to place Britain in an international setting

has meant a failure to appreciate the importance of America for the

British economy before 1870 and of colonial expansion after that

date.39

IV

This comment has been undertaken in no spirit of captiousness.

Professor Rostow's work has been a ready source of inspiration to

those working in the field of 19th-century history and there is much

illumination to be gained from his writings on many aspects of the

economic growth and development of the British economy. These

matters have not been mentioned here because the object of this brief

essay was not to write a general commentary upon Professor Rostow's

work, but to indicate certain of the weaknesses in his analysis which

were held to vitiate his particular theoretical approach. It is freely

admitted that the full documentation of a number of the general

criticisms is not yet available, but it will not be at our elbows until

the kind of questions which have been posed receive their answers

one way or the other.

To sum up. There are two separate parts of the criticism which

has been made here. One is concerned with matters of fact; the

second with the adequacy of Rostow's theoretical model. On the

questions of fact, it has been argued that in two vital periods of 19thcentury economic history Professor Rostow has misread the evidence.

One is the period of the Great Depression and the other concerns

the I84os and the I85os. With regard to this earlier period, it must

80

PAST AND PRESENT

be pointed out that if, as has been suggested here, I847 cannot be

regarded as marking the transition from one distinctive period

to another, the implications for the social historian are farreaching. Although it was the 20th century which invented

the phrase " The Hungry Forties," the contemporary writings of

Engels and the Reports inspired by Chadwick abundantly confirm

the poverty and the misery of the labouring millions. At the same

time, the rapid rate of growth of the economy in the I83os and I84os

suggests that it is in this period that must be sought the origins of the

changing climate of opinion of the I85os. The engineers New Model

and the rapid decline of the Chartist movement occurred within

three years of April ioth, I848, and a closer appreciationof the phases

of growth within the economy will permit an analysis of these events

that relies less upon the personal and the fortuitous than has been

customary hitherto.40

The theoretical weakness of Professor Rostow's work stems first,

it is suggested, from an undue concentration upon the characterof

investment and from a failureto consider adequately, or indeed hardly

at all, changes in its volume. Second, it has been argued that an

analysis which focusses attention upon a few variables within the

economy does violence in its conclusions to the complexities and the

complications of historical change; and that moreover, no set of

abstractionscan ignore the crucial importance of certain institutional

actors; for institutional factors become, in time, economic forces.

There is much else that could be discussed in a comment upon

Professor Rostow's analysis. Mr. Matthews has recently made some

critical remarks about the hypothesis of the inventory cycle, and

elsewhere has published some detailed comments upon the twovolume Growth and Fluctuation of the British Economy which was

the forerunner to Professor Rostow's own volume.41 There is

further the general problem of the usefulness of any analysis which

does not take account of structural changes occuring within the

economy, a criticism from which Professor Rostow's work is not

entirely free despite his discussion of the role of harvests, the

inventory cycle and the long term investment cycle. What he

appears to ignore are changes in industrial organisation and the

industrial structure. It is doubtful whether it is theoretically

possible to include the small master economy within a predominantly agrariansociety under the same umbrella as the mature

industrial society of 1914, and apply to both a set of rather

simplified theoretical assumptions, from the application of which

the same phenomena can be expected to be deduced. This is a

BRITISH ECONOMY OF THE I9TH CENTURY

matter which demands the attention of both historians and

economists.

While this note must be understood as a criticism of the attempt

to force a complicated historical story into the strait jacket provided

by a too simple theoretical model, there is no intention to decry

the importance of a theoretical approachin general to the problems

of economic growth. We need more, not less, theoretical understanding; we need however to check continually our theories

with what we believe to be the facts.

University College, Hull.

John Saville.

NOTES

1 Among the more recent exceptions to this statement may be noted M. H.

Dobb, Studies in the Development of Capitalism (1946) and R. C. 0. Matthews,

A Study in Trade Cycle History: Economic Fluctuations in Great Britain I833-42

(1954).

2 W. W. Rostow, British Economy of the g9th Century, O.U.P.

(1948),

hereafter referred to as Rostow.

3 The phrase is from D. H. Robertson, 'New Light on an Old Story',

Economica, (Nov. 1948), p. 297. This review of the British Economy by Prof.

Robertson is the most illuminating comment upon Prof. Rostow's theoretical

approach that I have read.

4 Rostow, p. I2.

I have ommitted from the discussion, for reasons of space, Prof. Rostow's

analysis of the years I790-I815.

6 W. T. Layton and G. Crowther, An Introduction to the

Study of Prices,

Chart I.

(I935),

7 W. W. Rostow, The Historical Analysis of the Terms of Trade, Econ. Hist.

Rev. 2nd. Ser., IV, No. I (I951), p. 56.

8 A. F. Burns and W. C. Mitchell, Measuring Business Cycles, (1946), p. 440.

9 Rostow, p. o0.

10ibid.

11J. H. Clapham, An Economic History of Modern Britain, Vol. I, (I926),

Preface.

12 See esp. T. S. Ashton, ' The Standard of Life of the Workers in England,

1790-I830', Journ. Econ. Hist., Supplement, (I949).

13E. J. Hobsbawm, ' The Labour Aristocracy in I9th Century Britain',

Democracy and the Labour Movement, (ed. Saville I954), p. 208, note I.

4 Rostow, p. I9.

16 Matthews, op. cit., pp. 220-223.

16C. Clark, The Conditions of Economic Progress, (I940), pp. 448-454;

W. A. Lewis, Economic Survey, (I949), pp. I94-5 ; Rostow, The Historical

Analysis of the Terms of Trade, op. cit., p. 58 ff.

17

A. H. Imlah, 'Real Values in British Foreign Trade', Journal of

Economic History (1948), pp. I33-I52.

18 Rostow, p. 19.

82

PAST AND PRESENT

19 The revised series were incorporated in a volume published in Jena in 1940.

Wachstum und Wachtstumformen den Englischen Industrie-wirtschaft von 1700

bis zur Gegenwart. Few copies of this volume, which I have not seen, reached

Britain. See also W. Hoffman, ' The Growth of Industrial Production in

Great Britain: A Quantitative Study,' Econ. Hist. Rev., 2nd Ser. II, No. 2,

(1I949), pp. 162-180.

20 For Prof. Rostow's brief comments on Hoffman's

index, see pp. 33-4, note

I and p. 223, note 13. The index was also extensively used in A. D. Gayer,

W. W. Rostow and A. J. Schwartz, The Growth and Fluctuations of the British

Economy, 1790-1850, 2 vols. (1953). This work was written before Prof.

Rostow's own British Economy of the 19th Century and is a detailed source for

many of his generalisations.

21

22

Rostow,

p. 88.

Rostow, p. 25.

2s The statistics of the volume and movement of capital investment have been

taken from the following sources: A. H. Imlah, ' British Balance of Payments

and Export of Capital, 1816-1913', Econ. Hist. Review, 2nd Ser., V, No. 2,

(1952), pp. 208-239 ; J. H. Lenfant, ' Great Britain's Capital Formation,

1865-1914', Economica, N. S. XVIII, No. 70 (May 1951), pp. 151-168 ; E. H.

Phelps Brown and S. J. Handfield-Jones, ' The Climateric of the i89os': A

study in the Expanding Economy,' Oxford Economic Papers, IV, No. 3, (Oct.

I952), pp. 266-307.

:' Rostow, Ch. IX.

26

Rostow, p. 88.

Rostow, p. 12, note I.

Rostow, p. 48.

"8Rostow, pp.

34-5.

29

The most useful discussions are in J. Hilton, ' Statistics of Unemployment . . .' J. R. S. S. (Feb. 1923) pp. I54-205; W. H. Beveridge Unemployment, A Problem of Industry, (1909), esp. Ch. 2; A. L. Bowley, 'The

Measurement of Empioyment: An Experiment,' J. R. S. S., (July 1912),

pp. 791-829.

sOD. H. Robertson in Economica, loc. cit.

81Lenfant, loc. cit.

32

One of the earliest statements is in H. S. Foxwell, ' The Financing of

Industry and Trade', Econ. Journal, (Dec. 1917), pp. 502-552. The most

widely known discussion is in the Committee on Industry and Trade, Pt. 2, Ch. 4.

83 D. L. Burn, The Economic History of Steel Making, (1940), esp. Ch. XI.

'4J. B. Jefferys, Trends in Business Organisation in Great Britain since i856 ...

(Ph.D. thesis, London 1938).

l6reprinted in Economica, (Feb. 1951).

36

Dobb, op. cit., p. 286.

37Preface to An Economic History of Modern Britain, Vol. 2, (1932).

38 Addendum to Directors Preface, A. D. Gayer, W. W. Rostow and A. J.

Schwartz, The Growth and Fluctuations of the British Economy, 1790-1850,

2 Vols., (1953).

39 See, for

example, Brinley Thomas, Migration and Economic Growth. A

Study of Great Britain and the Atlantic Economy (1954).

40 It is perhaps relevant here to note that the Webbs, in their History of

Trade Unionism, (1894), began the chapter on the New Spirit and the New

Model with the year 1843.

41 Matthews,

op. cit., pp. 74-5; 'The Trade Cycle in Britain, I790-I850',

Oxford Economic Papers, N.S. (Feb. 1954) pp. 1-32

26

27

BRITISH ECONOMYOF THE I9TH CENTURY

APPENDIX

INVESTMENT

AS A PROPORTION

I.

OF THE NATIONAL

Total Net

Domestic Investment

I87I

I872

I873

I874

I875

I876

I877

I878

I879

I880

I88

I882

I883

I884

I885

I886

I887

I888

I889

1890

...

...

...

...

...

...

..

...

...

...

...

...

...

..

..

..

.

..

.

. .

.

...

..

.

...

.

...

.

...

...

.

...

...

...

8.4

8.7

9.9

7.7

6.4

9.2

0.2

8.o

5.2

8.o

8.8

8 .9

7.8

4.2

4.7

5

5.6

7.5

8. I

7.0

83

INCOME.

Foreign

Investment

7.5

9-5

6.9

6.2

4.4

I.7

I.0

I.4

3.6

3.4

5.8

5.0

4. I

6.6

5.5

6.9

7.3

7.3

6.o

7.0

Note: Domestic Investment data from E. H. Phelps Brown and S. J. HandfieldJones, The Climacteric of the I89os : A study in the Expanding Economy,

Oxford Economic Papers, (October I952), Appendix C, Table 4.

Foreign Investment data from A. H. Imlah, ' British Balance of

Payments and Export of Capital, I816-I913,' Econ. Hist. Review, 2nd

Ser., V, No. 2, (1952).

National Income data from A. R. Prest, 'National Income of the

United Kindgom I870-I946,' Economic Journal, (March I948).

PAST AND PRESENT

84

APPENDIX

II.

GREAT BRITAIN.

Production Movements - Annual Average Percentage Rate of Change.

(From W. Hoffman: 'Ein Index der Industriellen Produktion fur

Grossbritannien seit dem I8. Jahrhundert', Weltwirtschaftliches

Archiv. 1934).

Producers'

Goods.

I815-1820

1820-1825

1825-1830

I830-1835

I835-1840

I840-1845

I845-1850

I85o-I855

I855-i86o

I86o-I865

I865-1870

I870-1875

I875-1880

I88o-I885

I885-1890

I890-1895

I895-1900

1900-1905

1905-19I0

Total

Production.

2. I

2.4

6.2

4.4

3.7

3.9

3.6

2.5

5. I

5 -5

3 -3

6.6

5.I

3. I

4 I

2.4

4.6

2.3

3.2

3.0

3 -7

3. I

I .3

3.0

3 5

2.8

I .I

I .9

2 3

2.6

o.8

o.8

3. I

2.3

2.0

I .3

o.8

I. I

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5814)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (844)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- Passion Libretto PDFDocument146 pagesPassion Libretto PDFSean100% (6)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- A Concept Paper of Social Issues in The PhilippineDocument9 pagesA Concept Paper of Social Issues in The Philippinecamile buhanginNo ratings yet

- SlursDocument90 pagesSlurs51ck13rNo ratings yet

- Aesthetic Labia Minora SubrayadoDocument11 pagesAesthetic Labia Minora SubrayadoAlexNo ratings yet

- Slaughtering Operations (Large Animals) NC IIDocument100 pagesSlaughtering Operations (Large Animals) NC IIBeta TesterNo ratings yet

- Tesis Poética de Octavio PazDocument199 pagesTesis Poética de Octavio Pazclaugtzp-1No ratings yet

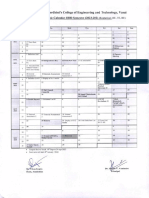

- Academic Calendar 2023-2024 ODD SEM Ver 1Document1 pageAcademic Calendar 2023-2024 ODD SEM Ver 1Mayank PatilNo ratings yet

- Stat Problems With AnswersDocument3 pagesStat Problems With Answersolga orbaseNo ratings yet

- Week 24Document1 pageWeek 24stephtrederNo ratings yet

- 20 Modal and Auxiliary VerbsDocument11 pages20 Modal and Auxiliary Verbsenglishvideo100% (1)

- Mario Jimenez v. Karen Wizel, 11th Cir. (2016)Document15 pagesMario Jimenez v. Karen Wizel, 11th Cir. (2016)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- The Spanish Legion's Hymn To DeathDocument8 pagesThe Spanish Legion's Hymn To DeathJuan A. Caballero PrietoNo ratings yet

- Tes Strategies To Develop Independent LearnersDocument19 pagesTes Strategies To Develop Independent LearnersNurhayati ManaluNo ratings yet

- Natural Language ProcessingDocument37 pagesNatural Language ProcessingAkashNo ratings yet

- REVIEW hk2 Grade 3Document9 pagesREVIEW hk2 Grade 3Minh PhamNo ratings yet

- Unit 1 Langfocus Three Star PDFDocument1 pageUnit 1 Langfocus Three Star PDFValeriaSantaCruzNo ratings yet

- Adc PWMDocument26 pagesAdc PWMShivaram Reddy ManchireddyNo ratings yet

- Experiencing Revival in Our Day-Ps Ashish RaichurDocument8 pagesExperiencing Revival in Our Day-Ps Ashish RaichurapcwoNo ratings yet

- Cran-Hill Ranch PresentationDocument19 pagesCran-Hill Ranch Presentationsarajmiller324No ratings yet

- Post-Modernism Styled: Reflection PaperDocument3 pagesPost-Modernism Styled: Reflection PaperMarcusNo ratings yet

- ING Bank Annual Report 2015, P. 26 PDFDocument286 pagesING Bank Annual Report 2015, P. 26 PDFJasper Laarmans Teixeira de MattosNo ratings yet

- PalmaDocument24 pagesPalmaAdrian ToaderNo ratings yet

- Understanding The Mystery: Weighing Cessationist and Continuationist Debate of Prophecy in The Pauline EpistlesDocument88 pagesUnderstanding The Mystery: Weighing Cessationist and Continuationist Debate of Prophecy in The Pauline EpistlesDidedla;,No ratings yet

- Iep Parent QuestionnaireDocument2 pagesIep Parent Questionnaireapi-447390096No ratings yet

- Welly@unissula - Ac.id: Welly Anggarani, Sandy Christiono, Prima AgusmawantiDocument6 pagesWelly@unissula - Ac.id: Welly Anggarani, Sandy Christiono, Prima Agusmawantinabilah syahirahNo ratings yet

- CSCE-365: Please Make Sure The Exam Has 3 Parts and 4pages Including The Cover Page and Answer SheetDocument4 pagesCSCE-365: Please Make Sure The Exam Has 3 Parts and 4pages Including The Cover Page and Answer SheetEtsegennet LidyaaNo ratings yet

- 4.2.1 Default VTP ConfigurationsDocument9 pages4.2.1 Default VTP ConfigurationsmmasliniaNo ratings yet

- Reaction Paper To RH LawDocument3 pagesReaction Paper To RH LawJuliette RavillierNo ratings yet

- Rule 122Document3 pagesRule 122deveraux_07No ratings yet

- Cloud Computing: Abin Thomas Mathew Martin Sebastian III-bca Marian College KuttikkanamDocument7 pagesCloud Computing: Abin Thomas Mathew Martin Sebastian III-bca Marian College Kuttikkanammartinwaits4uNo ratings yet