Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Perception and The Mimetic Mode in The Novels of Balzac and Robbe-Grillet

Perception and The Mimetic Mode in The Novels of Balzac and Robbe-Grillet

Uploaded by

Maryam AnsariOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Perception and The Mimetic Mode in The Novels of Balzac and Robbe-Grillet

Perception and The Mimetic Mode in The Novels of Balzac and Robbe-Grillet

Uploaded by

Maryam AnsariCopyright:

Available Formats

This article was downloaded by: [University of Iowa Libraries]

On: 16 March 2015, At: 11:25

Publisher: Routledge

Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954

Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH,

UK

Kentucky Romance Quarterly

Publication details, including instructions for

authors and subscription information:

http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vzrq20

Spatial Perception and the

Mimetic Mode in the Novels of

Balzac and Robbe-Grillet

John A. Fleming

University of Toronto

Published online: 09 Jul 2010.

To cite this article: John A. Fleming (1977) Spatial Perception and the Mimetic

Mode in the Novels of Balzac and Robbe-Grillet, Kentucky Romance Quarterly, 24:2,

209-219, DOI: 10.1080/03648664.1977.9928141

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03648664.1977.9928141

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the

information (the Content) contained in the publications on our platform.

However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no

representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness,

or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views

expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and

are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the

Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with

primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any

losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages,

and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or

indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the

Content.

Downloaded by [University of Iowa Libraries] at 11:25 16 March 2015

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes.

Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan,

sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is

expressly forbidden. Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

SPATIAL PERCEPTION AND THE MIMETIC MODE

IN THE NOVELS OF BALZAC AND ROBBE-GRILLET

Downloaded by [University of Iowa Libraries] at 11:25 16 March 2015

John A. Fleming

One of the difficulties for many readers of Balzac or Robbe-Grillet lies in the

detailed and frequent description of the physical world to be found in the novels

of both. Readers of Balzac have often skipped or skimmed these lengthy

descriptions of setting while potential readers of Robbe-Grillet have sometimes

rejected his novels altogether as unreadable. Such reactions suggest a

misunderstanding of the nature and function of their respective uses of setting

and call for some attempt at explanation. At the same time a broader question

also arises because most readers see that these two superficially similar uses of

setting are in fact profoundly different although they have no very clear understanding of this difference.

It is my contention that a fundamentally opposite way of viewing the external

world is at work in the novels of Balzac and Robbe-Grillet and that their individual differences may be tied to certain generalized psychic conditions

related to differing perceptions of space. If we as readers fail to respond to

Balzacs descriptions of the physical world it is in part because his settings no

longer correspond to the realities of contemporary perceptual experience,

although paradoxically they may continue to satisfy our literary expectations.

On the other hand if we find Robbe-Grillet unreadable it is because the physical

universe as he describes it represents a radical new ordering of perceptual experience which we have not as yet accepted, in the contemporary novel at

least, conditioned as we are by the literary traditions of what may be called the

mimetic and representational forms of the nineteenth century.

Although Balzac and Robbe-Grillet both use the physical universe extensively in their creation of. a particularized fictional world their conception of the

physical setting and its relationship to man is entirely different. The declared attitudes of both toward the physical world are too well known to require treatment here, but we should perhaps recall their basic positions before attempting

any comparative study of what the texts themselves express.

For Balzac the environment is an influence upon and a reflection of

character. Toute sa personne explique la pension comme la pension implique

sa personne he says of Mme Vauquer. Environment in a biological sense

forms and motivates character; setting in a fictional sense explains to the reader

what Grandet is and how he lives.

Downloaded by [University of Iowa Libraries] at 11:25 16 March 2015

2 10

Kentucky Romance Quarterly

Robbe-Grillet on the other hand feels that the physical world simply is. It has

no significance in itself, although it is subject to that which man chooses to project upon it falsely: Or le monde nest ni signifiant. ni absurde. II est tout

simplement. . . .auteur de nous. defiant la meute de nos adjectifs animistes ou

menagers, les choses sont 16. Leur surface est nette et lisse, intacte, sans eclat

louche ni transparence.2 As a result the landscapes of Robbe-Gritlet present a

neutral face to the reader. They neither explain character nor motivate action in

the usual sense.

These differing concepts of the physical world have important aesthetic consequences for the presentation and perception of the physical setting in the

novels of Balzac and Robbe-Grillet. Since both rely heavily upon objective

descriptive passages of great length and abundance a certain similiarity would

seem to exist at first glance. Le Pdre Goriot begins in somewhat the same way

as La Jalousie with the detailed description of a house. Yet our reactions to

these two dwellings are immediately distinct. Before making any comparison

however it would be useful to look more closely at two of Balzacs most famous

houses, the Maison Vauquer and the Maison Grandet.

In both cases we have an elaborate and detailed description spread over

many pages and interspersed with other material. We see each house in

characteristic detail, its position in the town, the quarter, the street. There is

only one Maison Vauquer, one Maison Grandet, and the reader is constantly

given the specifics of form and position necessary to establish this fact. The

authenticity of both is guaranteed for u s by their precise location in geographic

space and a catalogue of observable features. Balzac takes his distance upon

raw experience in mimetic terms:

La rnaison OG sexploite la pension bourgeoise appartient i Mrne Vauquer. Elle est

situee dans le bas d e la rue Neuve-Saint-GeneviPve, i Iendroit od le terrain

sabaisse vers la rue de IArbalhte par une pente si brusque et si rude que les

chevaux la rnontent ou la descendent rarernent. . . .Nu1 quartier de Paris nest

plus horrible, ni. disons-le, plus inconnu. La rue Neuve-Sainte-Genevihve surtout

est cornrne u n cadre d e bronze, le seul qui convienne 2 ce r6cit. auquel on ne

saurait trop preparer Iintelligence par des couleurs brunes. par des idees

.

graves

La facade d e la pension donne sur un jardinet. en sorte que la rnaison tornbe i

angle droit sur la rue Neuve-Sainte-Genevisve. oii vous la voyez coup6e dans sa

profondeur. Le long de cette facade. entre la rnaison et le jardinet. rBgne un

cailloutis en cuvette. large dune toise devant lequel est une allee sabke. bordee d e

geraniums. de lauriers-roses et de grenadiers plantes dans de grands vases en

faience bleue et blanche.3

,

Balzac is out to convince us of the actual existence in the real world of the

Maison Vauquer and to make us feel through his description something of its

inhabitants and their way of life. The same is true of Grandets dwelling. There

is an appeal to both sense and sentiment:

Spatial Perception and the Mimetic Mode

211

Downloaded by [University of Iowa Libraries] at 11:25 16 March 2015

II se trouve dans certaines villes de province des maisons dont la vue inspire une

melancolie 6gale 2 celle que provoque les cloitres les plus sombres. les landes les

plus temes ou les ruines les plus tristes. Peut-&re y-a-t-il 2 la fois dans ces rnaisons

et le silence du cloitre. et Iaridite des landes. et les ossements des ruines. . . .

Ces principes de melancolie existent dans la physionomie dun logis sit& 2

Saumur. , .

Eighteen pages later we have the faCade of the Maison Grandet described in

detail as Grandet himself has been presented in the intervening space:

Les trous in6gaux et nombreux que les intemgries du c h a t y avaient bizanernent

pratiques donnaient au cintre et aux jambages de la baie Iapparence des pierres

vermiculOes d e Iarchitecture franqaise et quelque ressemblance avec le porche

d u n e geBle. Au-dessus du cintre r6gnait un long bas-relief d e pierre dure sculptee.

representant les quatre Saisons. figures deji rongees et toutes noires. Ce bas-relief

etait surmont6 dune plinthe saillante. sur laquelle selevaient plusieurs d e ces

v6gktations dues au hasard, des pari6taires jaunes, des liserons, des convolvulus.

du plantain, et un petit cerisier assez haut dej2.

The Maison Vauquer and the Maison Grandet as well as their environs are seen

not as simple visual forms but as qualified materially and sentimentally. Both

are reflections not only of real places and presumably real structures, but of

their owners as well. The melancholy and decay of the Maison Grandet find

their cause in the nature of Grandet as Mme Vauquers boarding-house mirrors

the coquetry and cheap display of the widow herself.

At the same time these environments act upon the readers emotions to

create a more general atmosphere coincident with the action of the two novels.

They explain to the reader what is to follow, and prepare him psychologically

and emotionally for the unfolding of a drama. Their function is to give perspective internally, by situating the various elements of the narration within the

frame of the novel, and externally, by the situation in historical time and space

of verifiable points of reference. The reader finds himself ensconced at a certain

angle and distance from what is to be told. However as details accumulate the

natural model is rendered not necessarily in its reality but in its appearance, in

other words, impressionistically. What we see is not as important as what we

are meant to feel, hence the disorder of many of Balzacs descriptions: La rue

Neuve-Sainte-Genevikve surtout est comme un cadre d e bronze, le seul qui

convienne 2 ce rQcit, auquel on ne saurait trop prQparer Iintelligence par des

couleurs brunes, par des idQesgraves. . . .

Several techniques contribute to these impressionistic effects: the use of

affective vocabulary (horrible, graves, mQlancolie. sombre, ternes,

tristes, froid) ; figurative language and the anthropomorphization of objects

(comme un cadre d e bronze. les ruines les plus tristes, les ossements des

ruines, la physionomie dun logis); and finally visual color, red. rose, purple,

green, blue, and white in the first instance, yellow, green, white and perhaps

Downloaded by [University of Iowa Libraries] at 11:25 16 March 2015

212

Kentucky Romance Quarterly

red in the second. Here sense perception carries with it an implicit value and

emotion.

Although the banana plantation in La Jalousie is also seen, the house

described tells us little of its inhabitants. Nor does it have any typical significance

as bourgeois boarding house or provincial manor. Stripped of all allusive

values, it exists in its own time-space continuum, location unspecified,

historically, geographically and chronologically adrift. Robbe-Grillet is not trying

to convince us of its existence in the real world nor even trying to make us see it

in the usual way, but using it, as we discover later, both to destroy our

customary perceptions and to reveal indirectly the inner tensions of his

narrator:

Maintenant Iornbredu pilier-le pilier qui soutient Iangle sud-ouest d u toit-divise

en deux parties dgales Iangle correspondant de la terrasse. Cette terrasse est une

large galerie couverte, entourant la rnaison sur trois de ses c6tds. Cornrne sa

largeur est la rnerne dans la portion rnddiane et dans les branches latdrales, le trait

dornbre projet6 par le pilier arrive exacternent au coin de la rnaison; rnais il sarrete

Ib. car seules les dalles de la terrasse sont atteintes par le soleil. qui se trouve

encore trop haut dans le ciel.

Superficially the three passages cited are similar: each describes a concrete

reality observed in some detail and with considerable precision. Yet this very

precision is where Robbe-Grillet and Balzac diverge. Balzac accumulates, piling

object upon object, detail upon detail, in a proliferation of qualities and values

until he achieves a general effect. In contrast it is difficult to think of a single

scene in Robbe-Grillets novels in which there is an abundance of objects or any

implied value at ail. A few objects in an essentially simple scene are refined and

dissected until the setting emerges not as characterized or impressionistically

defined, but rather as a system of geometric functions. The geometric and

situational language used at times by Balzac establishes objects in their external

relations one to the other-Mme Vauquers boarding house is at such-and-such

a spot on the rue Neuve-Sainte-Genevikve, the house is at right angles to the

street, a sandy walkway parallels the faGade, and so forth. Above the arch of

Grandets doorway there is a bas-relief surmounted by a protruding plinth . . .

etc. Depth perspectives are thus established which coincide with Balzacs concept of character and plot. Robbe-Grillets backgrounds have no such function.

The geometry of his descriptions remains mathematical, abstract and in the end

non-representational. Normal perspective disappears as depth relations resolve

themselves into surfaces and planes. The pillar at the south-west corner of the

roof divides the corresponding angle of the terrace into two equal halves; since

the length of the terrace is the same in its median part as it is in the lateral

branches, the shadow reaches precisely to the corner of the house, etc. In other

words, objects are described in terms of their geometric functions and not as

elements which can be situated in visually distinct depth perspectives. The

resulting abstract structure of Robbe-Grillets backgrounds initiates a reality

Downloaded by [University of Iowa Libraries] at 11:25 16 March 2015

Spatial Perception and the Mimetic Mode

213

which is dependent upon its own logic and not upon any resemblance to the

natural world in contrast to the description of Gobsecks room, the antiquarians

shop in La Peau de Chagrin or Birotteaus renovations. The section of tomato

in Les Gommes, the dock in Le Voyeur, the streets and rooms in Dons le

labyrinthe, the maison d e rendez-vous and its garden, all reduce the overt

appearance of natural or man-made backgrounds to synergetic systems of interacting lines and forces because a different concept of the physical world leads

Robbe-Grillet away from Balzacs techniques into a presentation generally

devoid of color, figurative language, anthropomorphization or affective

vocabulary.

Balzacs settings charged with meaning both explicit and implicit correspond

to an action and characters defined in perspective and depth (although not

always successfully). Robbe-Grillets backgrounds with their denaturalized

objects d o not even carry the normal sense of the things which they detail

(houses are to be lived in, tomatoes are to be eaten, etc.). Objects seem independent of their human uses as Roland Barthes has observed.6 In this way

setting reflects the minimal use of anecdote, action and characterization in his

novels through the destruction of meaningful content. The setting appears at

any given moment as a flat surface devoid of anthropomorphic meaning, a

formal arrangement of planes which refuses emotional and psychological

significance and which destroys three dimensional space. There is no depth

perspective in visual terms as there is no profundity in terms of the significance

of objects and decors. A phrase in Dons le labyrinthe (Paris: Union Gkngrale

&Editions, 10118, 1969) sums it up thusly: au lieu des perspectives spectaculaires auxquelles ces enfilades d e maisons devraient donner naissance, il

ny a quun entrecroisement d e lignes sans signification, la neige qui continue

d e tomber Btant au paysage tout son relief. . . . (p. 16).

The physical world is simply there and the form alone is what matters, the

way in which the lines and surfaces intersect, parallel each other, and so forth:

Le bord de pierre-une ar&tevive, oblique, b Iintersection de deux plans perpendiculaires: la paroi verticale fuyant tout droit vers le quai et la rampe qui rejoint le

haut de la digue-se prolonge 2 son extremite superieure en haut de la digue. par

une ligne horizontale fuyant tout droit vers le quai.7

Although this is a literal description of what is seen, it creates at the same

time a pattern of lines whose order, unity and logic lie in the articulation of its

various component parts: oblique, A Iintersection d e deux plans, perpendiculaires, tout droit vers le quai, qui rejoint, horizontale. The description is not of objects finally but of their abstract structures and their relationships. This is also true of Robbe-Grillets descriptions even when no specifically

geometric vocabulary is used. Where Balzacs explanatory setting stands in

relation to action and character through its contentual element, Robbe-Grillets

descriptive background derives its meaning from its articulation and distribution

within the overall formal structure.

Downloaded by [University of Iowa Libraries] at 11:25 16 March 2015

2 14

Kentucky Romance Quarterly

One can say that because of this difference almost any given background in

Balzac could be replaced by any other background with the same or similar

contentual qualities without disruption to the sense of the novel. The flowers

mentioned above could be other flowers, the faGade of Grandets house could

be architecturally altered without damaging the sense of the novel because the

constituent elements of Balzacs novels d o not stand in formal relationship one

to the other but depend rather upon a common content.

Robbe-Grillets descriptions on the other hand could not be changed without

radically altering the fundamental structure and consequently the sense of his

novels because their meaning derives from their precise form and position in

the structure of the whole. The engraving hanging in the room occupied by the

narrator in Darp le labyrinthe gradually assumes its meaning through assimilation into the real decor which surrounds it, the two becoming so intermingled

that differentiation after a time becomes impossible. The engraving per se is

meaningless except in its formal relationships with the other elements of the

novel which in this case provide the external point of reference as the real

world does for a Balzac novel.

La Jalousie, to take another example, depends upon particular angles and

planes for the revelation of its psychological and thematic content although

such content does not and cannot exist a priori and apart from the formal

relationships which are created in each readers private perceptions as he reads.

The first few lines of the novel cited above are not simply an objective view of a

particular house although this is not apparent until the passage can be placed

within a wider context.

Unlike the psychological implications which are a part of Balzacs

backgrounds, the psychological significance of the setting in La Jalousie is only

gradually discovered by the attentive reader through a slow accumulation of

geometric forms as seen within a severely limited focus. Only when the larger

system has been grasped can the meaning of any part be manifest. Because the

natural world is not perceived as significant in itself but rather in its abstract and

formal arrangement. Robbe-Grillets novels demand an intellectual rather than

a sense perception of the setting. Through the formal relationships of elements

within a given scene and the overall articulation of scenes within a novel like La

Jalousie an emotional tension is created and revealed which conveys the

jealousy and sexual fantasies of the husband. The rows of banana plants, the

chairs arranged on the veranda, the ice cube melting in a glass, the layout of the

house, these elements in themselves reveal nothing about A and Franck or the

observing eye. Yet the mental patterns formed by their relationships draw the

reader into the novel and force him to find a significance based upon his own

perceptions. Any other plantation house, any other set of objects, would have

meant another novel since their points of contact could not have been the

same, nor their effect upon the reader. The physical background in Dons le

lobyrinthe or Lo maison d e rendez-uous functions in much the same way and is

closely tied as it is in La Jalousie to the problem of distance.

Downloaded by [University of Iowa Libraries] at 11:25 16 March 2015

Spatial Perception and the Mimetic Mode

215

The distance Balzac establishes aims at an atmosphere of factual reality

through its detachment and its self-conscious mimetism: . . . vous la voyez

coup& dans sa profondeur. , . (Goriot, p. 8).All observers of the scene will

see roughly the same thing. The physical world is presented from a distance as

if observed by a n interested and yet uninvolved observer in an impressionistic

manner, whether it be for the revelation of character and situation or the creation of an atmosphere. Omniscient narrator and fictional personae who think

aloud (Rastignacs oc6an d e boue, Goriot. p. 276) seem to take the same

distance upon reality.

Robbe-Grillets descriptions on the contrary even when third person as in Les

Gommes or at times Le Voyeur, are close-in, observed by an eye which is

totally committed yet seemingly objective inasmuch as overt coloring and

analogy are usually excluded. It is the selection and ordering of, in themselves,

objective fragments of perceptual experience which allow action and characters

to exist. The plantation in La Jalousie may be ugly or beautiful; no opinion is

either expressed or implied. In any case such an opinion would be irrelevant.

The subjective effect so much discussed by the critics comes rather from the

deforming closeness, intensity and frequency of the elements used. This

precision of detail obscures the natural world as the microscope fractures the

surface of objects. (Comparisons have sometimes been made with the

techniques of magic realism.) So exact is it that the seemingly objective

existence of the world of appearances is destroyed leaving in its wake an abstract pattern whose truth is unrelated to verifiable sense data. La Jalousie like

the other works of Robbe-Grillet could not exist without this fracturing of appearances and, on a larger scale, narration so that the reader must focus on

relationships and systems rather than on self-contained significances. It is only

through the things which register upon the eye of the psychotic narrator in La

Jalousie for example, and the gradual accumulation of these geometric

molecular images that the emotions he experiences can be conveyed. The

erotic fantasies of Mathias in Le Voyeur are similarly developed through certain

recurring aspects of his environment such as the much analysed figure-eights.

Reality is refracted rather than reflected through the choices made necessary by

the nature of the observing consciousness. Moving back from the fragments

presented the reader reconstructs the observing eye and experiences a set of

concomitant emotions.8

While there may be some development in a limited sense when Balzac continues to add details to a previously described object or setting the meaning of

the text is not dependent upon structural accumulations and overlaps as in

Robbe-Grillet. The overall effect is fixed by our initial impression and further

details are simply meant to add their weight to the original treatment: I1 est

maintenant (after 18 pages) facile d e comprendre toute la valeur d e ce mot: la

maison d M . Grandet. cette maison, pble. froide, silencieuse, situ6e en haut de

la ville. et abritQepar les ruines des remparts. Perspectives are thus provided

through the situation in narrative (as well as real) time and space of objects and

Downloaded by [University of Iowa Libraries] at 11:25 16 March 2015

216

Kentucky Romance Quarterly

decors. By continually proving the existence of Grandet and his environment,

Balzac affirms the reality of a single external world subject of course to time and

physical process, but continuous and comprehensible as well.

The return to previously mentioned scenes and objects in Robbe-Grillets

novels is entirely different in that it destroys any sense of perspective, clarity or

absolute. Previous impressions are radically modified, even contradicted, as

images and scenes are laid upon one another until the lines for all their individual precision blur and like the jealous husband or the wandering soldier we

cannot be sure where obsession ends and external reality begins. The canals in

Les Gommes. the chairs arranged on the terrace in La Jalousie, the streets and

buildings in Dans le labyrinthe return again and again modified at each encounter in the consciousness of the narrator until the common denominators,

oppositions and modifications reveal a significance within a larger system of

lines and forces.

Although at first glance then Robbe-Grillets descriptions, like Balzacs, may

seem to hold a mirror up to the physical world, the organization into volumes

and planes soon destroys any mimetic effect. Concrete language leads into the

realm of the non-figurative and the non-representational within each given

frame as each frame in turn loses its momentarily imitative quality within the

patterns of the whole. The reader is confronted with material so specific and

well ordered in its relationships that its formal qualities subvert his accepted notions of meaning and force an unaccustomed apprehension of the scene

presented.

Perhaps Wilhelm Worringers notion of abstraction and empathy provides

some clue to the finally opposed realisms Balzac and R~bbe-Grillet.~

According to Worringer the urge to empathy, that is. naturalistic, organic,

representational art forms is the result of an accommodation and confidence

between man and the phenomena of the physical universe: _. .the precondition for the urge to empathy is a happy pantheistic relationship of confidence

between man and the phenomena of the external world. . . (p. 15).In such a

situation the artist expresses his feelings about the world through the projection

into his work of the lines and forms of the organically vital. The nineteenth century with its faith in material progress on the one hand and its sense of mans

place within the cosmic forces of nature on the other (the romantics,

Baudelaires correspondances, Balzacs Swedenborgian mysticism, the concept of pathetic fallacy) would suggest in Worringers terms an urge to empathy and art forms imitative of the natural world.

Balzacs decors would seem to coincide with this concept of empathy. They

express through their explicit mimetism a belief in the organic complicity of man

and the natural world. Man shapes the environment in his own image, and the

environment in turn exerts powerful influences upon man in a continuing symbiotic process. Through the elaboration of a fictional setting within not only

each novel but the series of novels which comprises La Comedie humaine

Balzac aims at a complete and rational description of an integrated physical

Downloaded by [University of Iowa Libraries] at 11:25 16 March 2015

SpatialPerception and the Mimetic Mode

217

world in which each part has its place and contributes its weight to the overall

system. Technically this leads in individual descriptive passages to the development of dominants supported or formed by clusters of related elements bound

together in a single impression and functioning as an organic whole. Such

passages are dependent for the most part upon massing effects and affective

techniques, a feeling-oneself-into the forms of the natural world in Worringers terminology, in which the artists attempts to approximate his work to

the facts of organic experience correspond to mans vision of himself in and of

the world.

Robbe-Grillets physical world on the other hand seems to correspond to

Worringers notion of abstraction, that is, the artistic impulse which reveals

through linear and geometric forms a metaphysical conflict inspired in man by a

dread of the obscure, entangled, inexplicable and uncontrollable phenomena

of the outside world (absurd man in an absurd universe?), in particular an immense dread of space. lo The suppression of three dimensionality through the

use of simple line and its development in purely geometric and planimetric

regularity, Worringer believes, is the inevitable response to this fear of the

obscurity and entanglement of phenomena in space for it is space which links

things to one another and gives them their relativity. By removing the object

from its natural context, by purifying it of its dependence on life, by approximating it to its absolute value, the artist seeks relief from the flux of appearances and the relativity of meaning: The primal artistic impulse has

nothing to d o with the rendering of nature. It seeks after pure abstraction as the

only possibility of repose within the obscurity and confusion of the world picture

and creates out of itself, with instinctive necessity, geometric abstraction (p.

44).

So too Robbe-Grillet (like the Cubists) seeks an equilibrium not to be found in

the capriciousness of the organic and an approximation to naturalistic forms.

By suppressing three dimensional space within the novel as painters and

sculptors had done long since, Robbe-Grillet realizes formally the work of arts

separation from contentual and contextual significance and endeavours to find

absolute forms within the perceptual data of lived experience.

Robbe-Grillets novels all reveal this struggle to isolate individual elements, to

see volumes and outlines and to apprehend the thing-in-itself, the attempt to

fix the external world, to find certainty and repose in a universe which refuses

human values and meanings. This is true at the level of the rCcit as well as in the

broader sense with which we are concerned here. But the solid, tangible,

discrete entities which make up at the start, as in Balzacs novels, his closed and

self-sufficient world are immediately questioned, negated, destroyed through

the reduction of both objects and scenes to systems of relationships which articulate in geometric schemata surfaces. contours and interfaces, and which

eliminate the referential and the contentual from the elements of the physical

decor. (As in the Baroque no single integrating perspective is privileged; as in

Downloaded by [University of Iowa Libraries] at 11:25 16 March 2015

2 18

Kentucky Romance Quorterly

Cubism a multiplicity of theoretically simultaneous and often contradictory

views is proposed.)

Internally the absolute values sought for through the precision and intensity

of the descriptive passages lead to a necessary and non-referential abstraction

of individual material elements in their tangible mimetic concreteness. Repetitions, superpositions and overlaps continue this evacuation of anthropornorphic meaning within the larger narrative context by substituting for a clear and

understandable presentation of physical decor, in perspective, a setting which

suppresses the cognate-organic in order to focus upon abstract relationships.

The intensity and precision of descriptive detail and the repetitions and overlaps

of both objects and scenes are upon the narrative and structural plane no other

than the working out of a new set of perceptual values in which the desired

clear material individuality of objects, not in their organic similitude but in their

absolute value, is the goal of artistic volition and psychic necessity.

By extracting (abstracting) in this way from the natural forms of the physical

world and human experience their structures and formal relationships to the

detriment of anthropomorphic and organic values Robbe-Grillet expresses a

fundamental psychic condition of our time. The will to abstraction coincides

with mans increasing doubts about the certainties of empirical knowledge and

the usefulness of human perception as an agent of understanding, the final

resignation of knowledge, as Worringer puts it.

While settings mirror the reassuring existence of an understandable world,

however cruel, in Balzacs novels they become in the works of Robbe-Grillet

signs of emotional, psychological and above all perceptual rupture and instability which transcend their own simple existence in the direction of an eternal here

and now freed from appearances and the contingency of the organic, subject

only to the laws of geometric abstraction.

UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO

NOTES

1. I cannot agree with A . J. Mount in The Physical Setting in Balzacs Comedie humaine. University of Hull Occasional Papers in Modern Languages, n o 2 (Hull: Univ. of

Hull Publications. 1966).p. 27. who opposes this view of the links between setting and

character: . . . the widely accepted view that physical background is an active ingredient

in the drama, forming character and determining action does not bear close examination

2. Pour un nouueau roman (Paris: Gallimard. Collection IdCes. 1963).p . 21.

3. LePPre Goriot (Paris: Garnier. 1963).p . 7 .

4. Eug6nie Grandet (ParisSarnier. 1961).p. 1

5. La Jalousie (Paris: Les Editions de Minuit. 1957),p. 1.

6. Essais Critiques (Paris: Editions du Seuil. 1964).p 31.

.I

Downloaded by [University of Iowa Libraries] at 11:25 16 March 2015

Spatial Perception and the Mimetic Mode

219

7. Le Voyeur (Paris: Les Editions d e Minuit. 1954, p. 13.

8. For a detailed description of narrative and temporal structure in La Jalousie see

Bruce Morrissettes Les romans de Robbe-Griller (Paris: Les Editions d e Minuit. 1963),

pp. 111-147.

9. Abstraction and Empathy, trans. Michael Bullock (New York: International

Universities Press, 1953),pp. 3-48.

10. Worringer proposes the same psychic conditions at the root of the will to form in

the abstract art of primitives and the abstraction in art of certain highly developed civilizations.

11. 1 am indebted in a general way for parts of my discussion of the geometric aspects

of Robbe-Grillets descriptions to Elly JaffP-Freem. Alain Robbe-Griller et la peinture

cubiste (Amsterdam: Meulenhoff, 1966).

You might also like

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5810)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (843)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (346)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- Amy Hawkins Differentiation Tiered LessonDocument10 pagesAmy Hawkins Differentiation Tiered Lessonapi-427103633No ratings yet

- Rizz EvaluationDocument2 pagesRizz EvaluationMohd ShahrizanNo ratings yet

- Mixed Methods and Processes in Applied Linguistics ResearchDocument343 pagesMixed Methods and Processes in Applied Linguistics ResearchSCARLET PAULETTE ABARCA GARZONNo ratings yet

- Excellence Success: Understand Yourself Using MBTIDocument3 pagesExcellence Success: Understand Yourself Using MBTIMuhammad Qamarul HassanNo ratings yet

- Passi's Test of CreativityDocument5 pagesPassi's Test of CreativityNupur Pharaskhanewala100% (1)

- Sapir-Whorf HypothesisDocument1 pageSapir-Whorf HypothesisMortega, John RodolfNo ratings yet

- Development of A Program To Increase Personal Happiness: Michael W. FordyceDocument11 pagesDevelopment of A Program To Increase Personal Happiness: Michael W. FordyceLaura MelgarejoNo ratings yet

- 01.08 Module 1 ExamDocument18 pages01.08 Module 1 ExamJoseph KnahNo ratings yet

- For AgainstDocument2 pagesFor AgainstLacrimioaraLeahu0% (1)

- Bus Comm Module 1Document8 pagesBus Comm Module 1Poonam DabariaNo ratings yet

- Victoria Guijarro SantosDocument1 pageVictoria Guijarro Santosmsg35No ratings yet

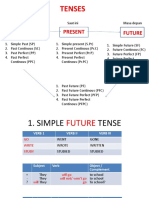

- Tenses: Past Present FutureDocument12 pagesTenses: Past Present FutureIka bella10No ratings yet

- Psychology Slides Section EDocument50 pagesPsychology Slides Section ERao ZeeshanNo ratings yet

- Introduction To The Narragansett LanguageDocument143 pagesIntroduction To The Narragansett LanguageFrank Waabu O'Brien (Dr. Francis J. O'Brien Jr.)100% (7)

- Markowitsch - A History of MemoryDocument39 pagesMarkowitsch - A History of MemoryricardoNo ratings yet

- The Trajectory of Attachment Trauma: Personality Disorders and Co-Occurring Substance Use DisordersDocument115 pagesThe Trajectory of Attachment Trauma: Personality Disorders and Co-Occurring Substance Use DisordersGary Freedman100% (1)

- Practical Problem SolvingDocument121 pagesPractical Problem Solvingalbertoca990100% (1)

- The Nature of ArtDocument12 pagesThe Nature of ArtDarren R. FlorNo ratings yet

- Pepsi Case StudyDocument8 pagesPepsi Case Studyapi-491557757100% (1)

- (Re - Work) Google's New Manager Training SlidesDocument121 pages(Re - Work) Google's New Manager Training Slidessufian26No ratings yet

- VR Design DocumentDocument12 pagesVR Design DocumentAastha GalaniNo ratings yet

- The D'Ni Student - by DomahrehDocument40 pagesThe D'Ni Student - by DomahrehLeMont A. NalogueNo ratings yet

- Posthumanist Applied LinguisticsDocument179 pagesPosthumanist Applied LinguisticsMabel QuirogaNo ratings yet

- Adults Lesson Plan Efl PDFDocument4 pagesAdults Lesson Plan Efl PDFapi-28972433388% (8)

- Derrida - Structure, Signs and PlayDocument17 pagesDerrida - Structure, Signs and PlayMary Mae100% (3)

- Week 5 Lesson 8 Standard Form Categorical Proposition PDFDocument3 pagesWeek 5 Lesson 8 Standard Form Categorical Proposition PDFJared Cuento Transfiguracion100% (1)

- Subject-Verb Agreement 1Document3 pagesSubject-Verb Agreement 1mawarNo ratings yet

- IB TOK 1 Resources Notes Lagemat PDFDocument85 pagesIB TOK 1 Resources Notes Lagemat PDFEdwin Valdeiglesias100% (1)

- Lesson Plan 6Document3 pagesLesson Plan 6api-259179075100% (1)

- Nursing Research and StatisticsDocument6 pagesNursing Research and StatisticsSathya PalanisamyNo ratings yet