Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Guardian - São Paulo's Guarani Indians Face Eviction - 24 April

Uploaded by

C_RigbyOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Guardian - São Paulo's Guarani Indians Face Eviction - 24 April

Uploaded by

C_RigbyCopyright:

Available Formats

Section:GDN BE PaGe:29 Edition Date:150424 Edition:01 Zone:

Sent at 23/4/2015 19:42

cYanmaGentaYellowblack

The Guardian | Friday 24 April 2015

Human rights

29

International

Indigenous Brazilians struggle to keep land

Villagers fear a new law

will allow industry to seize

already restricted plots

600

Claire Rigby Tekoa Pyau

From downtown So Paulo, in Brazil,

the Pico do Jaragu the crest of mountain ridge on the citys north-west horizon looks like a broken tooth, crowned

by a towering TV antenna. Just beyond

the rocky peak and down a steep, deeply

rutted, unmade road, lies the nascent

village of Tekoa Itakupe, one of the newest fronts in the indigenous peoples

struggle for land to call their own.

Once part of a coffee plantation, the

idyllic 72-hectare (177-acre) plot is now

occupied by three families from the

Guarani community who moved on to

the land last year after it was recognised

as traditional Guarani territory by Funai,

the federal agency for Indian affairs.

The group had hoped that would be

a first step on the road to its eventual

official demarcation as indigenous

territory, but they now face eviction

after a judge granted a court order to

the landowner, Antnio Tito Costa, a

lawyer and former local politician.

Ari Karai, the 74-year-old chief or

cacique of Tekoa Ytu, one of two established Indian villages at the base of the

peak, says the group intends to resist.

How can they evict us when this is

recognised Indian land? he says.

The dispute comes at a crucial time

for Brazils indigenous groups. This

month more than 1,000 indigenous

leaders met in Braslia to protest and

organise against PEC 215, a proposed

constitutional amendment that would

shift the power to demarcate indigenous

land from the executive to the legislature that is, from Funai, the justice

y

ministry and the president, by

decree, to Congress.

The Indians opposition

to placing demarcation in

the hands of Congress is easy

to understand: about 250 members

mbers

of Congress are linked to the powerful ruralist congressional caucus,

aucus,

representing interests such as agrong and

business and the timber, mining

energy industries. By contrastt there has

been only one indigenous member

mber of

Congress in the entire history of Brazil:

Mrio Juruna, a Xavante cacique,

que, who

served from 1983-87.

ector at

Fiona Watson, research director

Survival International, the Londonndonbased charity that campaigns for indigroved

enous people, said that if approved

PEC 215 would put the fox in

charge of the hen house.

C

Many Indians consider PEC

215 a move to legalise the theft

ft

and invasion of their lands by agribusiness. It will cause further delays,

wrangling and obstacles to recognicogni-

Number of Guarani

people living at

Tekoa Ytu reserve,

a four-acre site

with contaminated

natural water

tion of their land rights. The demarcation of Brazils indigenous territories,

specified in the 1988 constitution, was

supposed to have been completed by

1993. Twenty-seven years on, most of

the territory has been demarcated, with

517,000 Indians living on registered land

mainly in the Amazon region, but more

than 200 applications still in limbo.

Under Dilma Rousseff, Brazils president, fewer demarcations have been

decreed than during any government

since 1988, despite the announcement

last weekend of three demarcations in

the states of Amazonas and Par.

At Tekoa Ytu, Brazils smallest

demarcated indigenous reserve, about

600 Guarani Indians are living on four

acres (1.7ha) in squalid, insalubrious,

conditions. The natural pool where the

children used to swim lies silent owing

to contamination from a stream running

through a favela on the hillside above,

polluting with raw sewage the waterfall,

pool and river where the community

once washed, fished and drew water.

Tekoa Pyau, the larger of Jaragus

two established Indian communities,

is similarly impoverished. Children run

barefoot over packed earth studded with

litter and bits of broken brick. The community is making uncertain progress

through the demarcation process.

The strain shows on the face of

Tekoa Pyaus young cacique, Victor

F S Guaran, a 30-year-old who says

that without demarcation the community has no future. Its so complicated,

he says, grimacing.

Its all they have, but the village is

hardly the kind of the place they would

live had they a choice, says Guaran. Its

extremely poor. Many families get the

bolsa famlia, a federal benefit payment

for those with low incomes, but other

than that the community gets minimal

assistance from the state, Guaran says.

a

For Brazils indigenous communities,

lack of representation in or by governla

ment

is just the institutional face of the

m

discrimination they encounter daily.

d

Some of the people who live around

here say, theyre not real Indians,

h

theyre favelados, says Guaran, using

th

Franco da Rocha

10 miles

Pico do Jaragu

Guarulhos

Barueri

Suzano

So Paulo

Mau

Itapecerica

da Serra

Brazil

Cubatao

Praia Grande

the pejorative term for slum dwellers.

The politician Costa, in his petition to a

local court calling for an eviction, writes

about the Guaran at Itakupe with scorn,

calling them unemployed and unproductive, and describing their traditional

outfits as ridiculous fancy dress.

Confined to cramped villages and

often dismissed as backward, the communities poverty, inward-looking culture and long-standing lack of political

and social agency, make them invisible

to many of their fellow Brazilians, even

when theyre standing in plain sight.

When I go into the city centre, says

Guaran, people ask if Im Bolivian.

During the first of a series of anti-PEC

215 protests in So Paulo last year, he

says, bystanders asked why Indians

had come all the way from the Amazon to protest, unaware of the Jaragu

reservation just nine miles north of the

city centre, or of the Guaran living at

Parelheiros, 24 miles to the south.

By the end of those protests, there

were whites marching with us, says

Guaran. When I saw them painting

their faces and chanting alongside us it

was very emotional.

At Tekoa Itakupe, wearing a feathered

headdress and a buriti-fibre skirt that

he put on to receive guests, the cacique

Karai was showing visitors the village

crops: corn, manioc, sweet potato and

mango. By contrast to the difficult conditions in the villages below, Itakupe has

got fresh water from dozens of springs,

expanses of secondary growth Atlantic

forest, a waterfall, and 10-metre tall

mossy ruins deep in the valley, thought

to be from the time of the bandeirantes,

Brazils colonising pioneers. On the

other side of the valley is a long swath of

eucalyptus, a plantation kept by Costa.

Costa, who is 92, says the land has not

been permanently inhabited by Indians

as the constitution states it must be

to be eligible for indigenous culture

protection. Indians have never lived on

the land in question, he told Brazils R7

news last week. Or if there was ever an

Indian village at Jaragu, as they claim,

those were other times. Its over.

Karai is worried the children in the

villages below are losing their connection to nature. We dont want anything

from this land other than to live on it

and take care of it. His face crumples

suddenly as he speaks. There is no joy

for us in any of this. But were going to

resist, whatever happens. What choice

do we have? We have to guarantee the

survival of our people and our culture.

Similar resistance is taking place all

over Brazil, often in the face of extreme

adversity and even violence. The resistance is rapidly coalescing, he says.

At street protests and online, alliances, strategies and a sense of empowerment are being forged among Brazils

300-plus indigenous groups and with

the quilombola communities whose

members are descendants of escaped

Tekoa Itakupe

chief Ari Karai,

who has vowed to

fight for survival.

Below a member

of the community

Photograph:

Victor Moriyama

for the Guardian

slaves, and whose right to a homeland is

also threatened by PEC 215.

If the PEC 215 is passed this year, as

seems it will, the amendment will also

allow for reviews of past demarcations,

and bring in exceptions to exclusive use

of protected land, including leasing to

non-Indians and infrastructure building,

in the public interest. Guaran says:

Once its explained, everyone becomes

concerned, even the children.

Advertisement

Refurbishment Programme

for

The Embassy of Saudi Arabia - London

The Royal Embassy of Saudi Arabia London

declares its willingness to perform a comprehensive

refurbishment of the whole interior buildings

through open competition of companies specialised

in the required field.

For companies wishing to participate in this

competition please contact Mr. Mohammed AlJumaah on 0207 917 3062 of the Royal Embassy of

Saudi Arabia, 30 Charles Street, Mayfair, London,

W1J 5DZ to obtain the tender documents, in return

of paying the amount of 100.

Competitive companies must fulfil the following

criteria conditions:

1. Works must be priced according to the

specification documents delivered to Companies.

2. Offers must be submitted to the attention of Mr.

Mohammed Al-Jumaah in sealed envelope,

bearing only the recipients address and the

project reference (Companies refurbishment

of the interior buildings of the Embassy).

3. The offer must be accompanied with an (Offer

Bond) in a separate envelope, equivalent to

1% of the total value of the offer, valid for (4)

months from the date of the deadline. The bond

can be in a form of bank guarantee or company

cheque.

4. Details of the company profile justifying their

ability to successfully execute the works and a

list of the companys experience for the past (3)

years must be included in the company offer.

5. Deadline for receiving bids after (30) days from

this advert.

For any additional information regarding this tender

or to arrange an appointment to visit the site, please

contact Jessica by email (j.yanni12@gmail.com).

The Embassy will not accept any Bids not comply

with the terms mentioned

You might also like

- Refugee Nation: A Radical Solution to the Global Refugee CrisisFrom EverandRefugee Nation: A Radical Solution to the Global Refugee CrisisRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- Benchwarmer Ramon Dacawi Panagbenga Postscript: Perennials Keeping Baguio's Status As Flower City (First of Two Parts)Document3 pagesBenchwarmer Ramon Dacawi Panagbenga Postscript: Perennials Keeping Baguio's Status As Flower City (First of Two Parts)Robin DizonNo ratings yet

- Critique Paper - DeanneDocument5 pagesCritique Paper - DeanneAnne MarielNo ratings yet

- Convention On The Elimination of Racial Discrimination Shadow Report SubmissionDocument21 pagesConvention On The Elimination of Racial Discrimination Shadow Report SubmissionDavid BriggsNo ratings yet

- South American Native PeopleDocument3 pagesSouth American Native PeopleSarai Stefany Aparicio EspinozaNo ratings yet

- Ghetto Mirror OctoberDocument8 pagesGhetto Mirror OctoberGhetto Mirror KenyaNo ratings yet

- Project in GeoDocument6 pagesProject in GeoAldeon NonanNo ratings yet

- Dirahs Part ACT 1 PIKSPDocument3 pagesDirahs Part ACT 1 PIKSPjimwelluismNo ratings yet

- 2018 Indigenous Peoples' Day: Stories of Struggle: Iron Fists of The Military, CorporationsDocument2 pages2018 Indigenous Peoples' Day: Stories of Struggle: Iron Fists of The Military, CorporationsTintin BejarinNo ratings yet

- The Indigenous Peoples' Rights Act of 1997Document6 pagesThe Indigenous Peoples' Rights Act of 1997Nerry Neil TeologoNo ratings yet

- Fashion - CRIMES - 28.03 - No EmbargoDocument44 pagesFashion - CRIMES - 28.03 - No EmbargovictoriawildmanNo ratings yet

- Money TreesDocument6 pagesMoney TreesCintia DiasNo ratings yet

- Ibaloi HousesDocument14 pagesIbaloi HousesJesebel Ambales50% (2)

- Reparations For Slavery: - Krystoff KissoonDocument5 pagesReparations For Slavery: - Krystoff KissoonKrystoff Kissoon100% (2)

- Forgotten Villages: Struggling To Survive Under Closure in The West BankDocument48 pagesForgotten Villages: Struggling To Survive Under Closure in The West BankOxfamNo ratings yet

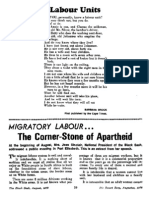

- Labour Units: The Corner-Stone of ApartheidDocument3 pagesLabour Units: The Corner-Stone of ApartheidjfcallariNo ratings yet

- IndigeneousDocument3 pagesIndigeneousglaipabonaNo ratings yet

- Stoke The Fires of Peasant Struggles: EditorialDocument14 pagesStoke The Fires of Peasant Struggles: EditorialnpmanuelNo ratings yet

- HR 1409 - Inquiry On The Relocation of Badjaos in Zamboanga CityDocument3 pagesHR 1409 - Inquiry On The Relocation of Badjaos in Zamboanga CityGabriela Women's PartyNo ratings yet

- Indigenous Nutritional Culture. Foundation of Foord SovereigntyDocument5 pagesIndigenous Nutritional Culture. Foundation of Foord SovereigntyCentro de Culturas Indígenas del PerúNo ratings yet

- Ancestral LandDocument1 pageAncestral LandLuisa SaliNo ratings yet

- CountryDocument6 pagesCountryYury HerreraNo ratings yet

- Custodians of The Land, Defenders of Our Future - A New Era in The Global Land RushDocument16 pagesCustodians of The Land, Defenders of Our Future - A New Era in The Global Land RushRBeaudryCCLENo ratings yet

- Custodians of The Land, Defenders of Our Future: A New Era in The Global Land RushDocument16 pagesCustodians of The Land, Defenders of Our Future: A New Era in The Global Land RushOxfamNo ratings yet

- Custodians of The Land, Defenders of Our Future: A New Era in The Global Land RushDocument16 pagesCustodians of The Land, Defenders of Our Future: A New Era in The Global Land RushOxfamNo ratings yet

- The Formation of Modern URUGUAY, C. 1870-1930 : Traditional Uruguay: Cattle A N D CaudillosDocument22 pagesThe Formation of Modern URUGUAY, C. 1870-1930 : Traditional Uruguay: Cattle A N D CaudillosSebastian Mazzuca100% (1)

- HAWTHORNE, W. Nourishing A Stateless Society During The Slave TradeDocument25 pagesHAWTHORNE, W. Nourishing A Stateless Society During The Slave TradeLeonardo MarquesNo ratings yet

- Homelands Essay MasterDocument9 pagesHomelands Essay Masterapi-680624821No ratings yet

- Colonia Aborigen 2005-2010Document27 pagesColonia Aborigen 2005-2010cintia medinaNo ratings yet

- Racism Towards Aboriginal People: John Bautista 1331 Words June 22, 2019Document5 pagesRacism Towards Aboriginal People: John Bautista 1331 Words June 22, 2019Vince SantosNo ratings yet

- Indigenous Farm and Resort in BaguioDocument4 pagesIndigenous Farm and Resort in BaguioEricka De ClaroNo ratings yet

- Chap 7 G1Document2 pagesChap 7 G1Essence RobinsonNo ratings yet

- Baron PinedaDocument292 pagesBaron PinedaMariusz KairskiNo ratings yet

- Documento 9Document3 pagesDocumento 9Luciana SanmiguelNo ratings yet

- April14 2012Document1 pageApril14 2012pribhor2No ratings yet

- Cultural Diversity WACCDocument5 pagesCultural Diversity WACCAlfonso Gumucio DagronNo ratings yet

- Culed 211-1st Paper RequirementDocument7 pagesCuled 211-1st Paper Requirementtheodoro yasonNo ratings yet

- Essay - Rojas With ReferencesDocument3 pagesEssay - Rojas With ReferencesJhojan RojasNo ratings yet

- Civil Guardianship and The Disempowerment of Yanomami CommunityDocument12 pagesCivil Guardianship and The Disempowerment of Yanomami CommunityMaria Kusheela MaroniNo ratings yet

- 1111 1347 Land Grabbing Contradicts Sustainable Development enDocument3 pages1111 1347 Land Grabbing Contradicts Sustainable Development enMohit OstwalNo ratings yet

- Task 8 Mask Identity Culture MaskDocument8 pagesTask 8 Mask Identity Culture Maskbry yyyNo ratings yet

- Prize of SugarDocument2 pagesPrize of Sugarclaud doctoNo ratings yet

- V 48Document17 pagesV 48Senkets RyukoNo ratings yet

- Culture in The CaribbeanDocument6 pagesCulture in The CaribbeanTishonna DouglasNo ratings yet

- Barangay Group 1Document30 pagesBarangay Group 1Raymond RomandaNo ratings yet

- President Allows UN Rights Body To Set Up Office in Manila: Philip C. Tubeza @inquirerdotnetDocument9 pagesPresident Allows UN Rights Body To Set Up Office in Manila: Philip C. Tubeza @inquirerdotnetRanielNo ratings yet

- Merging Result-MergedDocument24 pagesMerging Result-MergedPlanet UrthNo ratings yet

- MP, in SS PDFDocument4 pagesMP, in SS PDFFamularcano MarcusNo ratings yet

- Additional Historical Background of The KalingaDocument4 pagesAdditional Historical Background of The KalingaCleo Buendicho100% (1)

- Colonialism in The BahamasDocument8 pagesColonialism in The BahamasjosephwambuinjorogeNo ratings yet

- Poverty Project ProposalDocument9 pagesPoverty Project ProposalMoses Unongu67% (6)

- Reading 4Document27 pagesReading 4Joshua MendozaNo ratings yet

- Reading 4: in Defense of Ancestral Land: Land Rights. Baguio City: Tebteba FoundationDocument5 pagesReading 4: in Defense of Ancestral Land: Land Rights. Baguio City: Tebteba FoundationJoshua MendozaNo ratings yet

- Guarani Kaiowa S Political Ontology Singular Because CommonDocument26 pagesGuarani Kaiowa S Political Ontology Singular Because CommonCarlos Henrique Emiliano de SouzaNo ratings yet

- Warren 1999Document27 pagesWarren 1999Aknaton Toczek SouzaNo ratings yet

- Haiti and Australia, a future cooperation mutually beneficialFrom EverandHaiti and Australia, a future cooperation mutually beneficialNo ratings yet

- Philippine Collegian Tomo 89 Issue 6Document12 pagesPhilippine Collegian Tomo 89 Issue 6Philippine CollegianNo ratings yet

- Different Ethnic Groups in The PhilippinesDocument9 pagesDifferent Ethnic Groups in The PhilippinesJohn Ivan PabiloniaNo ratings yet

- HKT AUG2016 Features RioDocument4 pagesHKT AUG2016 Features RioC_RigbyNo ratings yet

- TOSP Amazon Cruise - Time Out Sao PauloDocument2 pagesTOSP Amazon Cruise - Time Out Sao PauloC_RigbyNo ratings yet

- Schnews Argentina Issue 2002Document4 pagesSchnews Argentina Issue 2002C_RigbyNo ratings yet

- Vai-Vai Carnival Feature, SELAMTA Magazine, Ethiopian AirlinesDocument9 pagesVai-Vai Carnival Feature, SELAMTA Magazine, Ethiopian AirlinesC_RigbyNo ratings yet

- Sao Paulo Hidden Gems SelamtaDocument1 pageSao Paulo Hidden Gems SelamtaC_RigbyNo ratings yet

- Observer Tech Monthly - GeekieDocument5 pagesObserver Tech Monthly - GeekieC_RigbyNo ratings yet

- Mônica Nador Profile - Art Review, Sept 2015Document5 pagesMônica Nador Profile - Art Review, Sept 2015C_RigbyNo ratings yet

- Re-Digesting Her Own WorkDocument1 pageRe-Digesting Her Own WorkC_RigbyNo ratings yet

- Buenos Aires Herald: BsAs Na ChoqueDocument1 pageBuenos Aires Herald: BsAs Na ChoqueC_RigbyNo ratings yet

- Her Name Is RioDocument2 pagesHer Name Is RioC_RigbyNo ratings yet

- Biennials Move To A Latin Beat After Decades of ControversyDocument1 pageBiennials Move To A Latin Beat After Decades of ControversyC_RigbyNo ratings yet

- Beatriz Milhazes Interview: There Is Nothing Simple About What I'm Doing'Document2 pagesBeatriz Milhazes Interview: There Is Nothing Simple About What I'm Doing'C_RigbyNo ratings yet

- Observer Magazine - How Latin American Women Are Changing Hip-HopDocument4 pagesObserver Magazine - How Latin American Women Are Changing Hip-HopC_RigbyNo ratings yet

- Cao Guimaraes - Art Review June 2015Document1 pageCao Guimaraes - Art Review June 2015C_RigbyNo ratings yet

- Casa Triângulo 25-Year Anniversary Exhibition Review, ArtReview, Summer 2014Document1 pageCasa Triângulo 25-Year Anniversary Exhibition Review, ArtReview, Summer 2014C_RigbyNo ratings yet

- Maid Equal in BrazilDocument3 pagesMaid Equal in BrazilC_RigbyNo ratings yet

- BATALHÃO DE TELEGRAFISTAS - Art NewsDocument1 pageBATALHÃO DE TELEGRAFISTAS - Art NewsC_RigbyNo ratings yet

- Oscar Niemeyer - Architectural LegacyDocument5 pagesOscar Niemeyer - Architectural LegacyC_RigbyNo ratings yet

- Tomie Ohtake Review - ArtReview - May 2013Document2 pagesTomie Ohtake Review - ArtReview - May 2013C_RigbyNo ratings yet

- Time Out Buenos Aires, Jan 2009Document1 pageTime Out Buenos Aires, Jan 2009C_RigbyNo ratings yet

- Mark Magazine 45, Aug-Sep 2013Document5 pagesMark Magazine 45, Aug-Sep 2013C_RigbyNo ratings yet

- The Insides Are On The Outside Review - ArtReview - Summer 2013Document2 pagesThe Insides Are On The Outside Review - ArtReview - Summer 2013C_RigbyNo ratings yet

- South China Morning Post - Citizenship Restored To Brazilian DissidentDocument4 pagesSouth China Morning Post - Citizenship Restored To Brazilian DissidentC_RigbyNo ratings yet

- The Insight Feature: Cut The CrapDocument5 pagesThe Insight Feature: Cut The CrapC_RigbyNo ratings yet

- The Insight Feature: Blood On The StreetsDocument6 pagesThe Insight Feature: Blood On The StreetsC_RigbyNo ratings yet

- Montevideo, Uruguay: Perfect Places Argentina & Uruguay, 2009Document8 pagesMontevideo, Uruguay: Perfect Places Argentina & Uruguay, 2009C_RigbyNo ratings yet

- The Mayan Riviera: Mexico City Guide Book, 2008Document4 pagesThe Mayan Riviera: Mexico City Guide Book, 2008C_RigbyNo ratings yet

- Time Out São Paulo 1, Nov 2010Document1 pageTime Out São Paulo 1, Nov 2010C_RigbyNo ratings yet

- The Insight Feature: City LimitsDocument6 pagesThe Insight Feature: City LimitsC_RigbyNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 - Societal ProblemsDocument10 pagesChapter 1 - Societal ProblemsRia de PanesNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of The Global Leaders Empowered To Alleviate Poverty (LEAP) ProgramDocument104 pagesEvaluation of The Global Leaders Empowered To Alleviate Poverty (LEAP) ProgramOxfamNo ratings yet

- 10 Nutritional Guidelines For Filipinos (Mga Gabay Sa Wastong Nutrisyon para Sa Pilipino)Document4 pages10 Nutritional Guidelines For Filipinos (Mga Gabay Sa Wastong Nutrisyon para Sa Pilipino)Paulene Rivera100% (1)

- TransformationDocument22 pagesTransformationOnno ManushNo ratings yet

- ResearchDocument10 pagesResearchGildred Rada BerjaNo ratings yet

- History of Urban SettlementsDocument103 pagesHistory of Urban Settlements200211555No ratings yet

- Risk and Resiliency Factors of Children in Single Parent FamiliesDocument17 pagesRisk and Resiliency Factors of Children in Single Parent Familiesapi-87386425100% (1)

- CA Ebook by Abhijeet SirDocument250 pagesCA Ebook by Abhijeet SirDevesh TripathiNo ratings yet

- The Philippines A Century HenceDocument5 pagesThe Philippines A Century HencezhayyyNo ratings yet

- Impact of Globalization On Indian AgricultureDocument6 pagesImpact of Globalization On Indian AgricultureGurpal Singh RayatNo ratings yet

- Unemployment Statistics in IndiaDocument2 pagesUnemployment Statistics in Indiaarchana_anuragiNo ratings yet

- GE 6 IE Assignment 2023 Set 1Document1 pageGE 6 IE Assignment 2023 Set 1Aman Ahmad AnsariNo ratings yet

- In The Midst of HardshipDocument11 pagesIn The Midst of HardshipnietahanaffiNo ratings yet

- Web-English ROA Report 2010Document304 pagesWeb-English ROA Report 2010junvNo ratings yet

- Urban HEART: Urban Health Equity Assessment and Response ToolDocument48 pagesUrban HEART: Urban Health Equity Assessment and Response ToolSiva Nayak100% (1)

- Word Social Inequality Essay HealthDocument8 pagesWord Social Inequality Essay HealthAntoCurranNo ratings yet

- The Inspiring Story of Suresh KamathDocument4 pagesThe Inspiring Story of Suresh Kamathvishal_000No ratings yet

- Explain The Concept of Urban GeographyDocument3 pagesExplain The Concept of Urban GeographyPrincess LopezNo ratings yet

- Socdie PrintDocument9 pagesSocdie PrintMaria Lucy MendozaNo ratings yet

- About WFP: Accountabilities/ResponsibilitiesDocument4 pagesAbout WFP: Accountabilities/ResponsibilitiesJill DagreatNo ratings yet

- President Ferdinand E. Marcos (1965-1986)Document5 pagesPresident Ferdinand E. Marcos (1965-1986)SVTKhsiaNo ratings yet

- Online RTI Request Form DetailsDocument2 pagesOnline RTI Request Form DetailsNeel BhattacharyaNo ratings yet

- Frankenstein Reading LogsDocument9 pagesFrankenstein Reading LogsAngela NiNo ratings yet

- New Microsoft PowerPoint Presentation On Lemon Tree HotelsDocument29 pagesNew Microsoft PowerPoint Presentation On Lemon Tree HotelsPrashanth SubramaniNo ratings yet

- A Million Voices: The World We Want: A Sustainable Future With Dignity For AllDocument52 pagesA Million Voices: The World We Want: A Sustainable Future With Dignity For AllZaq MosherNo ratings yet

- From Manual Workers To Wage Laborers Transformation of The Social Question (2003)Document497 pagesFrom Manual Workers To Wage Laborers Transformation of The Social Question (2003)Xandru FernándezNo ratings yet

- Bradford Essay QuestionsDocument2 pagesBradford Essay QuestionsRei Diaz ApallaNo ratings yet

- Food Losses During Food Processing As Food WasteDocument20 pagesFood Losses During Food Processing As Food WasteJyoti JhaNo ratings yet

- Weekly Fieldwork Report - Week 1Document7 pagesWeekly Fieldwork Report - Week 1Rishi Raj PhukanNo ratings yet

- SWOT Analysis of Bangladesh EconomyDocument14 pagesSWOT Analysis of Bangladesh EconomyIqbal HasanNo ratings yet