Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Civil Procedure Digest A2010 Prof. Victoria A. Avena

Uploaded by

Reinier Jeffrey AbdonOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Civil Procedure Digest A2010 Prof. Victoria A. Avena

Uploaded by

Reinier Jeffrey AbdonCopyright:

Available Formats

Civil Procedure Digest

A2010

Prof. Victoria A.

Avena

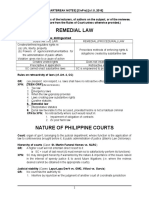

JUDICIAL POWER

CONSTITUTIONAL PROTECTION

PRESCRIBED JURISDICTION i.e. OVER

SUBJECT MATTER, BY LAW

SINDICO V DIAZ

440 SCRA 50

CARPIO-MORALES; October 1, 2004

NATURE

Petition for review on certiorari of a decision of the

RTC of Iloilo

FACTS

-Virgilio Sindico, is the registered owner of a parcel of

land, which he let the spouses Eulalio and Concordia

Sombrea cultivate, without him sharing in the

produce, as his "assistance in the education of his

cousins" including defendant Felipe Sombrea

-After the death of the Eulalio Sombrea, Felipe

continued to cultivate the lot

-On June 20, 1993, Sindico requested Felipes wife for

the return of the possession of the lot but the latter

requested time to advise her husband

-Repeated demands for the return of the possession

of the lot remained unheeded, forcing Sindico to file

a civil case before the RTC against the spouses

Sombrea for Accion Reivindicatoria with Preliminary

Mandatory Injunction

-The defendants filed a Motion to Dismiss, alleging

that the RTC has no jurisdiction over their person and

that as the subject matter of the case is an

agricultural land which is covered by the

Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Program (CARP) of

the government, the case is within the exclusive

original jurisdiction of the DARAB in accordance with

Section 50 of Republic Act 6657 (THE

COMPREHENSIVE AGRARIAN REFORM LAW OF 1988)

-The plaintiff filed an Opposition alleging that the

case does not involve an agrarian dispute, there

being no tenancy relationship or leasehold

agreement with the defendants.

-The RTC of Iloilo granted the Motion to Dismiss

-As their Motion for Reconsideration was denied by

the trial court, the plaintiffs, herein petitioners,

lodged the present Petition for Review on Certiorari

ISSUE

WON

the

Department

of

Agrarian

Reform

Adjudication Board (DARAB) has original and

exclusive jurisdiction over the case at bar

HELD

No.

Ratio. Jurisdiction over the subject matter is

determined by the allegations of the complaint. It is

not affected by the pleas set up by the defendant in

his answer or in a motion to dismiss, otherwise,

jurisdiction would be dependent on his whims.

Reasoning.The allegations in petitioners complaint

show that the action is one for recovery of

possession, not one which involves an agrarian

dispute.

-Section 3(d) of RA 6657 or the CARP Law defines

"agrarian dispute" over which the DARAB has

exclusive original jurisdiction as:

(d)

any

controversy

relating

to

tenurial

arrangements,

whether

leasehold,

tenancy,

stewardship or otherwise, over lands devoted to

agriculture,

including

disputes

concerning

farmworkers associations or representation of

persons in negotiating, fixing, maintaining, changing

or seeking to arrange terms or conditions of such

tenurial arrangements including any controversy

relating to compensation of lands acquired under this

Act and other terms and conditions of transfer of

ownership from landowners to farmworkers, tenants

and other agrarian reform beneficiaries, whether the

disputants stand in the proximate relation of farm

operator and beneficiary, landowner and tenant, or

lessor and lessee.

-Since petitioners action is one for recovery of

possession and does not involve an agrarian

dispute, the RTC has jurisdiction over it.

Disposition Petition is granted.

ground that the court had no jurisdiction of the

subject matter

FACTS

- On Dec 1907, Mla Railroad Co. began an action in

CFI Tarlac for the condemnation of 69,910 sq. m. real

estate located in Tarlac. This is for construction of a

railroad line "from Paniqui to Tayug in Tarlac," as

authorized by law.

- Before beginning the action, Mla Railroad had

caused to be made a thorough search in the Office of

the Registry of Property and of the Tax where the

lands sought to be condemned were located and to

whom they belonged. As a result of such

investigations, it alleged that the lands in question

were located in Tarlac.

- After filing and duly serving the complaint, the

plaintiff, pursuant to law and pending final

determination of the action, took possession of and

occupied the lands described in the complaint,

building its line and putting the same in operation.

- On Oct 4, Mla Railroad gave notice to the

defendants that on Oct. 9, a motion would be made

to the court to dismiss the action upon the ground

that the court had no jurisdiction of the subject

matter, it having just been ascertained by the

plaintiff that the land sought to be condemned was

situated in the Province of Nueva Ecija, instead of the

Province of Tarlac, as alleged in the complaint. This

motion was heard and, after due consideration, the

trial court dismissed the action upon the ground

presented by the plaintiff.

ISSUE/S

1. WON CFI Tarlac has power and authority to take

cognizance of condemnation of real estate located in

another province

2. WON Sec. 3771 of the Code of Civil Procedure and

1

JURISDICTION DISTINGUISHED FROM

VENUE

MANILA RAILROAD V ATTY. GENERAL

20 PHIL 523

MORELAND; December 11, 1911

NATURE

Appeal from CFI Tarlacs judgment dismissing the

action before it on motion of the plaintiff upon the

SEC. 377. Venue of actions. Actions to confirm title to real

estate, or to secure a partition of real estate, or to cancel clouds,

or remove doubts from the title to real estate, or to obtain

possession of real estate, or to recover damages for injuries to

real estate, or to establish any interest, right, or title in or to real

estate, or actions for the condemnation of real estate for public

use, shall be brought in the province were the lands, or some part

thereof, is situated; actions against executors, administrators,

and guardians touching the performance of their official duties,

and actions for account and settlement by them, and actions for

the distribution of the estates of deceased persons among the

heirs and distributes, and actions for the payment of legacies,

shall be brought in the province in which the will was admitted to

probate, or letters of administration were granted, or the

guardian was appointed. And all actions not herein otherwise

provided for may be brought in any province where the

Civil Procedure Digest

A2010

Act. No. 1258 are applicable and so the CFI has no

jurisdiction

- Procedure does not alter or change that power or

authority; it simply directs the manner in which it

shall be fully and justly exercised. To be sure, in

certain cases, if that power is not exercised in

conformity with the provisions of the procedural law,

purely, the court attempting to exercise it loses the

power to exercise it legally. This does not mean that

it loses jurisdiction of the subject matter. It means

simply that he may thereby lose jurisdiction of the

person or that the judgment may thereby be

rendered defective for lack of something essential to

sustain it. There is, of course, an important

distinction between person and subject matter are

both conferred by law. As to the subject matter,

nothing can change the jurisdiction of the court over

diminish it or dictate when it shall attach or when it

shall be removed. That is a matter of legislative

enactment which none but the legislature may

change. On the other hand, the jurisdiction of the

court over the person is, in some instances, made to

defend on the consent or objection, on the acts or

omissions of the parties or any of them. Jurisdiction

over the person, however, may be conferred by

consent, expressly or impliedly given, or it may, by

an objection, be prevented from attaching or

removed after it has attached.

Prof. Victoria A.

Avena

HELD

1.YES

Ratio Sections 55 and 562 of Act No. 136 of the

Philippine Commission confer perfect and complete

jurisdiction upon the CFI of these Islands with respect

to real estate in the Philippine Islands. Such

jurisdiction is not made to depend upon locality.

There is no suggestion of limitation. The jurisdiction

is universal. It is nowhere suggested, much less

provided, that a CFI of one province, regularly sitting

in said province, may not under certain conditions

take cognizance of an action arising in another

province or of an action relating to real estate

located outside of the boundaries of the province to

which it may at the time be assigned.

JURISDICTION OVER PERSON OF THE PLAINTIFF

defendant or any necessary party defendant may reside or be

found, or in any province where the plaintiff, except in cases

were other special provision is made in this Code. In case neither

the plaintiff nor the defendant resides within the Philippine

Islands and the action is brought to seize or obtain title to

property of the defendant within the Philippine Islands and the

action is brought to seize or obtain title to property of the

defendant within the Philippine Islands, the action shall be

brought in the province where the property which the plaintiff

seeks to seize or to obtain title to is situated or is found:

Provided, that in an action for the foreclosure of a mortgage upon

real estate, when the service upon the defendant is not personal,

but is by publication, in accordance with law, the action must be

brought in the province where the land lies. And in all cases

process may issue from the court in which an action or special

proceeding is pending, to be enforced in any province to bring in

defendants and to enforce all orders and decrees of the court.

The failure of a defendant to object to the venue of the action at

the time of entering his appearance in the action shall be

deemed a waiver on his part of all objection to the place or

tribunal in which the action is brought, except in the actions

referred to in the first sixteen lines of this section relating to real

estate, and actions against executors, administrators, and

guardians, and for the distribution of estates and payment of

legacies.

SEC. 55. Jurisdiction of Courts of First Instance. The

jurisdiction of Courts of First Instance shall be of two kinds:

1. Original; and 2. Appellate.

SEC. 56. Its original jurisdiction. Courts of First Instance

shall have original jurisdiction:

2. In all civil actions which involve the title to or possession

of real property, or any interest therein, or the legality of any

tax, impost, or assessment, except actions of forcible entry

into, and detainer of lands or buildings, original jurisdiction

of which is by this Act conferred upon courts of justice of the

peace.

2

2. NO

Ratio Sec. 377 contains no express inhibition against

the court. The prohibition provided therein is clearly

directed against the one who begins the action and

lays the venue. The court, before the action is

commenced, has nothing to do with it either. The

plaintiff does both. Only when that is done does the

section begin to operate effectively so far as the

court is concerned. The prohibition is not a limitation

on the power of the court but on the rights of the

plaintiff. It establishes a relation not between the

court and the subject, but between the plaintiff and

the defendant. It relates not to jurisdiction but to

trial. It simply gives to defendant the unqualified

right, if he desires it, to have the trial take place

where his land lies and where, probably, all of his

witnesses live. Its object is to secure to him a

convenient trial.

JURISDICTION OVER PERSON OF THE PLAINTIFF

- That it had jurisdiction of the persons of all the

parties is indisputable. That jurisdiction was obtained

not only by the usual course of practice - that is, by

the process of the court - but also by consent

expressly given, is apparent. The plaintiff submitted

itself to the jurisdiction by beginning the action. The

defendants are now in this court asking that the

action be not dismissed but continued. They are not

only nor objecting to the jurisdiction of the court but,

rather, are here on this appeal for the purpose of

maintaining that very jurisdiction over them. Nor is

the plaintiff in any position to asked for favors. It is

clearly guilty of gross negligence in the allegations of

its complaint, if the land does not lie in Tarlac as it

now asserts.

*DISTINGUISHED FROM VENUE

- The fact that such a provision appears in the

procedural law at once raises a strong presumption

that it has nothing to do with the jurisdiction of the

court over the subject matter. It becomes merely a

matter of method, of convenience to the parties

litigant. If their interests are best subserved by

bringing in the Court Instance of the city of Manila an

action affecting lands in the Province of Ilocos Norte,

there is no controlling reason why such a course

should not be followed. The matter is, under the law,

entirely within the control of either party. The

plaintiff's interests select the venue. If such selection

is not in accordance with section 377, the defendant

may make timely objection and, as a result, the

venue is changed to meet the requirements of the

law.

- Section 377 of the Code of Civil Procedure is not

applicable to actions by railroad corporations to

condemn lands; and that, while with the consent of

defendants express or implied the venue may be laid

and the action tried in any province selected by the

plaintiff nevertheless the defendants whose lands lie

in one province, or any one of such defendants, may,

by timely application to the court, require the venue

as to their, or, if one defendant, his, lands to be

changed to the province where their or his lands lie.

In such case the action as to all of the defendants not

objecting would continue in the province where

originally begun. It would be severed as to the

objecting defendants and ordered continued before

the court of the appropriate province or provinces.

While we are of that opinion and so hold it can not

affect the decision in the case before us for the

reason that the defendants are not objecting to

the venue and are not asking for a change

thereof. They have not only expressly submitted

themselves to the jurisdiction of the court but are

here asking that that jurisdiction be maintained

against the efforts of the plaintiff to remove it.

Civil Procedure Digest

A2010

Prof. Victoria A.

Avena

Disposition The judgment must be REVERSED and

the case REMANDED to the trial court with direction

to proceed with the action according to law.

JURISDITION VOID

ABBAIN V. CHUA

22 SCRA 748

Sanchez; February 26, 1968

NATURE

Direct appeal to the SC

FACTS

March 12, 1958: Tongham Chua commenced

suit for forcible entry and illegal detainer against

Hatib Abbain with the Justice of the Peace (JOP) Court

of Bongao, Sulu. Chua's averred that he is the owner

of a 4-hectare land together with the improvements

thereon mostly coconut trees located in Maraning,

Bongao, Sulu; that this land was donated to him by

his father, Subing Chua, in 1952 and from that date

he has assumed ownership thereof, taken possession

of the land and paid the corresponding taxes yearly;

that from 1952-1958, Abbain has been his tenant

and the two divided the fruits or copra harvested

therefrom on 50-50basis; that in 1957, Abbain by

means of force, strategy and stealth unlawfully

entered and still occupies the land in question after

Chua have repeatedly demanded of him to vacate

the premises due to his failure to give chuas share

of the several harvests.

LC:

JOP Managula rendered judgment directing

Abbain to vacate the premises and place Chua in

possession of the plantation, with costs. This

judgment was predicated upon the findings that

sometime before WWII, Abbain, because of financial

hardship, sold for P225 to Subing Chua the coconut

plantation; that after the sale, Abbain became the

tenant of Chua, the harvests of the land divided on a

50-50 basis; that subsequently, Subing Chua donated

the plantation to his son, Tongham Chua, and

Abbain, the same tenant of the father, continued to

be the tenant on the land.

- Abbain filed a petition in the CFI of Sulu against

Tongham Chua and Judge Managula, seeking relief

from the judgment of the JOTP Court anr/or

annulment of its decision with preliminary injunction.

He averred that the JOTP Court did not have

jurisdiction over the civil case and that said case

was within the exclusive original jurisdiction of

the Court of Agrarian Relations (CAR).

CFI of Sulu: petition dismissed without cause

-petitioner has not presented any proof or showing

of landlord and tenant relationship between the

parties" to bring the case within the jurisdiction of

the CAR, and that upon the allegations of the

complaint, the case is "clearly one of ejectment."

ISSUE

WON the JOTP Court has jurisdiction over the case

filed by Chua

HELD

NO

Ratio. Where a judgment or judicial order is void in

this sense it may be said to be a lawless thing, which

can be treated as an outlaw and slain at sight, or

ignored wherever and whenever it exhibits its head.

And in Gomez vs. Concepcion, this Court quoted

with approval the following from Freeman on

Judgments: "A void judgment is in legal effect no

judgment. By it no rights are divested. From it no

rights can be obtained. Being worthless in itself, all

proceedings founded upon it are equally worthless. It

neither binds nor bars any one. All acts performed

under it and all claims flowing out of it are void. The

parties attempting to enforce it may be responsible

as trespassers. The purchaser at a sale by virtue of

its authority finds himself without title and without

redress."

Since the judgment here on its face is void ab initio,

the limited periods for relief from judgment in Rule

38 are inapplicable. That judgment is vulnerable to

attack "in any way and at any time, even when no

appeal has been taken."

Reasoning. The provisions of Sec. 21 of RA 1199

(approved August 30, 1954), known as the

Agricultural Tenancy Act of the Philippines, read:

"SEC. 21. Ejectment; violation; jurisdiction. All

cases involving the dispossession of a tenant by the

landholder or by a third party and/or the settlement

and disposition of disputes arising from the

relationship of landholder and tenant, as well as the

violation of any of the provisions of this Act, shall be

under the original and exclusive jurisdiction of such

court as may now or hereafter be authorized by law

to

take

cognizance

of

tenancy

relations

anddisputes."

Sec. 7, RA 1267, creating the First Court of Agrarian

Relations, effective June 14, 1955, as amended by

Republic Act 1409 which took effect on September 9,

1955,provides:

"SEC. 7. Jurisdiction of the Court. The Court shall

have original and exclusive jurisdiction over the

entire Philippines, to consider, investigate, decide,

and settle all questions, matters, controversies or

disputes involving all those relationships established

by law which determine the varying rights of persons

in the cultivation and use of agricultural land where

one of the parties works the land."

- Chua's complaint was filed on March 12, 1958

long after RAs 1199, 1267 and 1409 were

incorporated in our statute books. Chua's complaint

positively averred that Hatib Abbain is his tenant on

a 50-50 sharing basis of the harvest; and that he

seeks ejectment of Hatib Abbain "due to his noncompliance of our agreement of his giving my share

of the several harvests he made." The JOTP Court

itself found that Abbain continued to be the tenant of

Chua after the latter became owner of the plantation

which he acquired from his father by virtue of a

donation; and that Abbain refused to give "the share

of his landlord of the harvest."

- If both the complaint and the inferior court's

judgment have any meaning at all, it is that the JOTP

Court had no jurisdiction over the case. Right at the

outset, the complaint should have been rejected.

Failing in this, the case should have been dismissed

during the course of the trial, when it became all the

more evident that a landlord-tenant relationship

existed. The judge had no power to determine the

case. Because

Chua's suit comes within the

coverage of Sec. 21, R.A. 1199 - that "cases involving

the dispossession of a tenant by the landholder,"

shall be under the "original and exclusive jurisdiction

of such court as may now or hereafter be authorized

by law to take cognizance of tenancy relations and

disputes", and the broad sweep of Section 7, RA

1267, which lodged with the CAR "original and

exclusive jurisdiction . . . to consider, investigate,

decide,

and

settle

all

questions,

matters,

controversies or disputes involving all those

relationships established by law which determine the

varying rights of persons in the cultivation and use of

agricultural land where one of the parties works the

land."

Jurisprudence has since stabilized the jurisdiction of

the CAR over cases of this nature. Such exclusive

authority is not divested by a mere averment on the

part of the tenant that he asserts ownership over the

Civil Procedure Digest

A2010

Prof. Victoria A.

Avena

land, "since the law does not exclude from the

jurisdiction" of the CAR, "cases in which a tenant

claims ownership over the land given to him for

cultivation by the landlord."

The judgment and proceedings of the Justice of the

Peace Court are null and void.

The judgment of the JOTP Court is not merely a

voidable judgment. It is void on its face. It may

be attacked directly or collaterally. Here, the

attack is direct. Abbain sought to annul the

judgment. Even after the time for appeal or review

had elapsed, appellant could bring, as he brought,

such an action. More, he also sought to enjoin

enforcement of that judgment. In varying language,

the Court has expressed its reprobation for

judgments rendered by a court without jurisdiction.

Such a judgment is held to be a dead limb on the

judicial tree, which should be lopped of' or

wholly disregarded as the circumstances

require.

Disposition The decision of the JOTP Court of Sulu is

annulled.

JURISDICTION BY ESTOPPEL

General rule:

SEAFDEC V NLRC (LAZAGA)

206 SCRA 283

NOCON, February 14, 1994

NATURE

Petition for certiorari to review the decision of the

NLRC

FACTS

-SEAFDEC-AQD is a department of an international

organization, the Southeast Asian Fisheries

Development Center. Private Respondent Lazaga was

hired as a Research Associate and eventually

became the Head of External Affairs Office of

SEAFDEC-AQD. However, he was terminated

allegedly due to financial constraints being

experienced by SEAFEC-AQD. He was supposed to

receive separation benefits but SEAFDEC-AQD failed

to pay private respondent his separation pay so

Lazaga filed a complaint for non-payment of

separation benefits, plus moral damages and

attorneys fees with the NLRC.

-In their ANSWER WITH COUNTERCLAIM, SEAFDEC

alleged that NLRC has no jurisdiction over the

case because: (1) It is an international organization;

(2) Lazaga must first secure clearances from the

proper departments for property or money

accountability before any claim for separation pay

will be paid (and clearances has not been paid)

COUNTERCLAIM: Lazaga had property accountability

and outstanding obligation to SEAFDEC-AQD

amounting to P27, 532.11 and that Lazaga was not

entitled to the accrued sick leave benefits due to his

failure to avail of the same during his employment

-LA: for Lazaga

-NLRC: affirmed LA, deleted attorneys fees and

actual damages

-SEAFDEC-AQD filed MFR, denied

ISSUES

1. WON SEAFEC-AQD is immune from suit owing to

its international character

2. WON SEAFDEC-AQD is estopped from claiming

that the court had no jurisdiction

HELD

1. YES

Ratio. Being an intergovernmental organization,

SEAFDEC including its departments enjoys functional

independence and freedom from control of the state

in whose territory its office is located.

Reasoning. One of the basic immunities of an

international organization is immunity from local

jurisdiction (immune from legal writs and processes

issued by the tribunals of the country where it is

found) that the subjection of such an organization to

the authority of the local courts would afford a

convenient medium thru which the host government

may interfere in their operations or even influence or

control its policies and decisions of the organization.

Such subjection to local jurisdiction would impair the

capacity of such body to discharge its responsibilities

impartially on behalf of its member-states.

2. NO

Ratio. Estoppel does not apply to confer jurisdiction

to a tribunal that has none over a cause of action.

Jurisdiction is conferred by law. Where there is none,

no agreement of the parties can provide one. Settled

is the rule that the decision of a tribunal not vested

with appropriate jurisdiction is null and void.

-The lack of jurisdiction of a court may be raised at

any stage of the proceedings, even on appeal.

-The issue of jurisdiction is not lost by waiver or by

estoppel

Exception:

SOLIVEN vs FASTFORMS PHILS.

440 SCRA 389

Sandoval-Gutierrez, October 18, 2004

NATURE

-petition for review on certiorari

FACTS

-Petitioner Marie Antoinette Soliven filed a complaint

for P195,155 as actual damages with P200k as moral

damages, P100k as exemplary damages and P100k

as attorneys fees against respondent Fastform

Phils., with the Makati RTC. It alleged that

respondent, through its president Dr. Escobar,

obtained a loan from petitioner (P170k) payable

within 21 days with 3% interest. On the same day,

respondent issued a postdated check for P170k +

P5k int. 3 weeks later, Escobar advised petitioner not

to deposit the check as the account from where it

was drawn had insufficient funds and instead

proposed that the P175k be rolled-over with 5%

monthly interest, to which the latter agreed.

Respondent issued several checks as payment for

interests for 5 months but thereafter refused to pay

its principal obligation despite petitioners repeated

demands.

-In its counterclaim, respondent denied obtaining the

loan and that it did not authorize Escobar to secure

said loan or issue checks as payment for interests.

After a trial on the merits, the court ordered

respondent to pay the amount of the loan plus

interest and attorneys fees, but moral and exemplary

damages as well as the counterclaim were

dismissed.

-Respondent filed a MFR questioning the courts

jurisdiction alleging that since the principal demand

(P195,155) did not exceed P200k, the complaint

should have been filed with the MTC, pursuant to RA

7691. The TC denied the MFR since the totality of the

claim exceeded 200k and since respondent was

estopped from questioning jurisdiction. On appeal,

the CA reversed the TC decision on the ground of

lack of jurisdiction and that respondent may assail

Civil Procedure Digest

A2010

Prof. Victoria A.

Avena

jurisdiction of the TC anytime even for the first time

on appeal. Petitioner filed an MFR which was denied

by the CA, hence this petition.

ISSUE (Members of religious group)

WON the trial court has jurisdiction over the case

HELD

NO.

Ratio. While it is true that jurisdiction may be raised

at any time, this rule presupposes that estoppel has

not supervened. Since respondent actively

participated in all stages of the proceedings before

the TC and even sought affirmative relief, it is

estopped from challenging the TCs jurisdiction,

especially since an adverse judgment had been

rendered. A party cannot invoke the jurisdiction of a

court to secure affirmative relief against his

opponent and after obtaining or failing to obtain such

relief, repudiate that same jurisdiction.

Reasoning. Section 3 of RA 7691 provides that

where the amount of the demand in the complaint

instituted in Metro Manila does not exceed P200k,

exclusive of interest, damages of whatever kind,

attys fees, litigation expenses and costs, the

exclusive jurisdiction over the same is vested in the

Metropolitan Trial court, Municipal Trial Court and

Municipal Circuit Trial Court.

-Administrative Circular 09-94 specifies guidelines in

the implementation of RA 7691. Par 2 of the Circular

provides that the term damages of whatever kind

applies only to cases where damages are merely a

consequence of the main action. In the instant case,

the main cause of action is the collection of the debt

amounting to P195k. The damages being claimed are

merely incidental and are thus not included in

determining the jurisdictional amount.

Disposition. WHEREFORE, the instant petition is

GRANTED

ONCE ATTACHED, JURISDICTION NOT

OUSTED BY SUBSEQUENT STATUTE

UNLESS SO PROVIDED

SOUTHERN FOOD SALES

CORPORATION vs. SALAS

206 SCRA 333

MEDIALDEA; Feb 18, 1992

NATURE

Petition for certiorari

FACTS

- July 1979 Private respondent Laurente (former

sale supervisor of petitioner corporation) was notified

and advised of his immediate termination for gross

neglect of duty and/or dishonesty

- August 1979 - Laurente instituted a civil action for

damages against SFSC and Siao, its manager

- Laurente filed a complaint for illegal dismissal

(labor case).

- January 1980 - Petitioners filed a motion to dismiss

on Civil Case, claiming that the jurisdiction should be

vested with the NLRC.

February 5, 1980 it was found that the

termination of the complainant was for a just and

valid cause

February 28, 1980 The court in Civil Case

deferred the determination of the motion to dismiss

until after trial.

- Petitioners filed a motion for reconsideration but it

was denied. Thus, this petition for the issuance of a

writ of preliminary injunction.

ISSUE

WON the respondent judge committed grave abuse

of discretion when it deferred the determination or

resolution of the motion to dismiss questioning the

jurisdiction of the court over claims for damages.

HELD

NO.

Ratio "(t)he rule is that where a court has already

obtained and is exercising jurisdiction over a

controversy, its jurisdiction to proceed to the final

determination of the cause is not affected by new

legislation placing jurisdiction over such proceedings

in another tribunal. The exception to the rule is

where the statute expressly provides, or is construed

to the effect that it is intended to operate as to

actions pending before its enactment. Where a

statute changing the jurisdiction of a court has no

retroactive effect, it cannot be applied to a case that

was pending prior to the enactment of the statute."

(Bengzon v. Inciong)

Reasoning

a.

Article 217 (a) (4) of the Labor Code as amended

by Section 9 of Republic Act No. 6715 clearly

provides that the labor arbiter shall have original

and exclusive jurisdiction to hear and decide

claims for actual, moral, exemplary and other

forms of damages arising from an employeremployee relationship. However, when the civil

case for damages was instituted in 1979, the

applicable law then was Article 217 (a) (3) of the

Labor Code as amended by Presidential Decree

No. 1367 (May 1, 1978) which provides that

Labor Arbiters shall not entertain claims for

moral or other forms of damages.

b. To require the private respondent to file a single

suit combining his actions for illegal dismissal

and damages in the NLRC would be to sanction

the retroactivity of Republic Act No. 6715 which

took effect on March 21, 1989, where the same

law does not expressly so provide, or does not

intend to operate as to actions pending before

its enactment, hence prejudicial to the orderly

administration of justice.

Disposition. The petition is DISMISSED for lack of

merit.

ACQUIRED JURISDICTION OVER THE

PERSON

Of the plaintiff

MANILA RAILROAD V ATTY. GENERAL

(page 1)

FACTS

-Manila Railroad filed an action for condemnation

proceedings in CFI of Tarlac when they knew that the

lands concerned are found in Nueva Ecija. Now they

are assailing the jurisdiction of CFI Tarlac.

ACQUIRED JURISDICTION OVER THE PERSON Of

the plaintiff: Procedure does not alter or change

that power or authority; it simply directs the manner

in which it shall be fully and justly exercised. To be

sure, in certain cases, if that power is not exercised

in conformity with the provisions of the procedural

law, purely, the court attempting to exercise it loses

the power to exercise it legally. This does not mean

that it loses jurisdiction of the subject matter. It

means simply that he may thereby lose jurisdiction

of the person or that the judgment may thereby be

rendered defective for lack of something essential to

sustain it. There is, of course, an important

distinction between person and subject matter are

both conferred by law. As to the subject matter,

Civil Procedure Digest

A2010

Prof. Victoria A.

Avena

nothing can change the jurisdiction of the court over

diminish it or dictate when it shall attach or when it

shall be removed. That is a matter of legislative

enactment which none but the legislature may

change. On the other hand, the jurisdiction of the

court over the person is, in some instances, made to

defend on the consent or objection, on the acts or

omissions of the parties or any of them. Jurisdiction

over the person, however, may be conferred by

consent, expressly or impliedly given, or it may, by

an objection, be prevented from attaching or

removed after it has attached.

- That it had jurisdiction of the persons of all the

parties is indisputable. That jurisdiction was obtained

not only by the usual course of practice - that is, by

the process of the court - but also by consent

expressly given, is apparent. The plaintiff submitted

itself to the jurisdiction by beginning the action. The

defendants are now in this court asking that the

action be not dismissed but continued. They are not

only nor objecting to the jurisdiction of the court but,

rather, are here on this appeal for the purpose of

maintaining that very jurisdiction over them. Nor is

the plaintiff in any position to asked for favors. It is

clearly guilty of gross negligence in the allegations of

its complaint, if the land does not lie in Tarlac as it

now asserts.

Of the defendant

1. by service of summons

2. by voluntary appearance

BOTICANO V CHU, JR

148 SCRA 541

PARAS; March 16, 1987

NATURE

Petition for review on certiorari seeking to reverse

and set aside CA ruling of denying MFR.

FACTS

- Eliseo Boticano is the registered owner of a Bedford

truck which is used in hauling logs for a fee. It was hit

at the rear by another Bedford truck owned by

Manuel Chu and driven by Jaime Sigua while loaded

with logs and parked properly by the driver Maximo

Dalangin at the shoulder of the national highway.

- Chu acknowledged ownership and agreed to

shoulder the expenses of the repair, but failed to

comply with the agreement. Boticano filed a

complaint at the CFI at Cabanatuan against Chu and

Sigua. Summons were issued but one was returned

unserved for Sigua wile the other served thru Chus

wife.

- Boticano moved to dismiss the case against Sigua

and to declare Chu in default. The Court granted the

motions and adduced from evidence that Chu is

responsible for the fault and negligence of the driver

under Art 2180 CC.

- Chu filed with the TC a notice of appeal and an

urgent motion for extension of time to file record on

appeal. Court granted the motions.

- Boticano filed a MTD the appeal and for execution,

but the appeal was still approved. The case was

brought to the CA. CA set aside the TC decision for

being null and void.

- Boticano filed an MFR with the CA to which CA

denied.

ISSUE/S

1. WON the question of jurisdiction of the court over

the person of the defendant cannot be raised for the

first time on appeal

2. WON CA erred in holding that Chu did not

voluntarily submit himself to the jurisdiction of the TC

despite his voluntary appearance

HELD

1. NO

Ratio The defects in jurisdiction arising from

irregularities in the commencement of the

proceedings, defective process or even absence of

process may be waived for failure to make seasonal

objections.

Reasoning The circumstances appear to show that

there was waiver by the defendant to allege such

defect when he failed to raise the question in the CFI

and at the first opportunity.

2. YES, he voluntarily submitted himself to the

courts jurisdiction.

Ratio Under Sec 23, Rule 14 ROC, the defendants

voluntary appearance in court shall be equivalent to

service. It has been held by the court that the defect

of summons is cured by the voluntary appearance by

the appearance of the defendant.

Disposition The assailed decision and resolution of

CA are reversed and set aside. The decision of the

CFI (now RTC) is reinstated.

3. by voluntary submission

RODRIGUEZ VS ALIKPALA

57 SCRA 455

CASTRO; June 25, 1974

NATURE

Petition for certiorari

FACTS

-Petitioner Rodriguez filed a case for recovery of the

sum of P5,320.00 plus interest, attorneys fees and

cost against Sps. Robellado.

-A writ of preliminary attachment was issued and

served to Fe Robellado at their store in Divisoria. Sps

Robellado pleaded to the Rodriguez for time before

the attachment to be effectively enforced. Rodriguez

agreed to the suspension of the judgment on the

condition that Fe Robellados parents, the now

respondents, Federico & Felisa Tolentino, to bind

themselves jointly and severally with the Robellados,

to pay the entire obligation subject of the suit. Felisa

Tolentino, being present, immediately agreed to this

proposal.

-A compromise agreement was then entered to by

the parties. The Rebellados subsequently failed to

comply with the terms of the compromise

agreement, thus prompting petitioner Rodriguez to

request the City Court for a writ of execution on the

properties of the Robellados and also of the

Tolentinos. The request was granted by the City

Court. The Tolentinos brought an action for certiorari

with the Court of First Instance of Manila. The CFI

rendered judgment excluding the Tolentinos from the

effects of the writ of execution. Thus this appeal.

ISSUE

WON the CFI erred in excluding the Tolentinos from

the effects of the writ of execution.

HELD

YES

-The contention of the CFI that the dispositive portion

of the judgment of the City Court does not explicitly

enjoin the Tolentinos to pay jointly and severally with

the Rebellados the amount due to the plaintiff, and

that the City Court never acquired jurisdiction over

Tolentinos and therefore cannot be bound by the

judgment rendered by said court, is erroneous.

Civil Procedure Digest

A2010

-The dispositive portion of the judgment of the City

Court approving the compromise and enjoining strict

compliance thereto by the parties is adequate for the

purpose of execution. Judgment on a compromise

need not specifically name a person to be subject of

execution thereof in obvious avoidance of repetition.

-On lack of jurisdiction of the court over the

Tolentinos: the Tolentinos freely and voluntarily

entered into the compromise agreement which

became the basis of judgment of the City Court.

Under the circumstances, the Tolentinos are

estopped the very authority they invoked. And even

assuming that estoppel lies, we cannot set aside the

principle of equity that jurisdiction over a person

not originally a party to a case may be

acquired, upon proper conditions, thru the

voluntary appearance of the person before the

court. By coming forward with the original litigants

in moving for a judgment on compromise and by

assuming such interest in the final adjudication of

the case together with the Robellados, the Tolentinos

effectively submitted themselves to the jurisdiction

of the City Court.

-Jurisdiction over the plaintiff can be acquired by

the court upon filing of the complaint. On the other

hand, jurisdiction over the defendants can be

acquired by the court upon service of valid summons

and upon voluntary appearance/submission of a

person in court.

- The order of the court was entered directing that

publication should be made in a newspaper, the

court directed that the clerk of the court should

deposit in the post office in a stamped envelope a

copy of the summons and complaint directed to

Palanca at his last place of residence.

- The cause proceeded in the CFI and Palanca not

having appeared, judgment was taken against him

by default. It was ordered that Palanca should deliver

said amount to the clerk of the court to be applied to

the satisfaction of the judgment, and it was declared

that in case of failure to satisfy the judgment, the

mortgage property located in the city of Manila

should be exposed to public sale.

- Payment was never made and the court ordered the

sale of the property. The property was brought in by

the bank.

- About seven years after the confirmation of this

sale, a motion was made by Vicente Palanca, as

administrator of the estate of the original defendant,

wherein the applicant requested the court to set

aside the order.

Prof. Victoria A.

Avena

ACQUIRED JURISDICTION OVER THE

RES

EL BANCO ESPAOL-FILINO v.

PALANCA

37 Phil. 921

STREET; March 26, 1918

FACTS

- A mortgage was executed by Palanca, as security

for a debt owing to him to the bank. After the

execution of this instrument, Palanca returned to

China where he died.

- As Palanca was a nonresident, it was necessary for

the bank to give notice to him by publication

pursuant to section 399 of the Code of Civil

Procedure. An order for publication was accordingly

obtained from the court, and publication was made in

due form in a newspaper of the city of Manila.

ISSUE

1. WON the order of default and the judgment

rendered thereon were void because the court had

never acquired jurisdiction over the defendant or

over the subject of the action.

2. WON the supposed irregularity in the proceedings

was of such gravity as to amount to a denial of due

process of law.

designated. The judgment entered in these

proceedings is conclusive only between the parties.

- Several principles: (1) That the jurisdiction of the

court is derived from the power which it possesses

over the property; (II) that jurisdiction over the

person is not acquired and is nonessential; (III) that

the relief granted by the court must be limited to

such as can be enforced against the property itself.

- In a foreclosure proceeding against a nonresident

owner it is necessary for the court, as in all cases of

foreclosure, to ascertain the amount due, as

prescribed in section 256 of the Code of Civil

Procedure, and to make an order requiring the

defendant to pay the money into court. This step is a

necessary precursor of the order of sale. It is clearly

intended merely as compliance with the requirement

that the amount due shall be ascertained and that

the defendant shall be required to pay it. As further

evidence of this it may be observed that according to

the Code of Civil Procedure a personal judgment

against the debtor for the deficiency is not to be

rendered until after the property has been sold and

the proceeds applied to the mortgage debt (sec. 260)

- Whatever may be the effect in other respects of the

failure of the clerk of the CFI to mail the proper

papers to the defendant in China, such irregularity

could in no wise impair or defeat the jurisdiction of

the court, for in our opinion that jurisdiction rests

upon a basis much more secure than would be

supplied by any form of notice that could be given to

a resident of a foreign country.

RULING

1. NO.

- The action to foreclose a mortgage is said to be a

proceeding quasi in rem, by which is expressed

the idea that while it is not strictly speaking an action

in rem yet it partakes of that nature and is

substantially such. The expression, "action in rem'

is, in its narrow application, used only with reference

to certain proceedings in courts of admiralty wherein

the property alone is treated as responsible for the

claim or obligation upon which the proceedings are

based. The action quasi in rem differs from the true

action in rem in the circumstance that in the former

an individual is named as defendant, and the

purpose of the proceeding is to subject his interest

therein to the obligation or lien burdening the

property. All proceedings having for their sole object

the sale or other disposition of the property of the

defendant, whether by attachment, foreclosure, or

other form of remedy, are in general way thus

2. NO.

- In a foreclosure case, some notification of the

proceedings to the nonresident owner, prescribing

the time within which appearance must be made, is

everywhere recognized as essential. To answer this

necessity the statutes generally provide for

publication, and usually in addition thereto, for the

mailing of notice to the defendant, if his residence is

known. It is merely a means provided by law

whereby the owner may be admonished by his

property is the subject of judicial proceedings and

that it is incumbent upon him to take such steps as

he sees fit to protect it.

- This mode of notification does not involve any

absolute assurance that the absent owner shall

thereby receive actual notice. The idea upon which

the law proceeds in recognizing the efficacy of a

means of notification which may fall short of actual

notice is apparently this: Property is always assumed

to be in the possession of its owner, in person or by

Civil Procedure Digest

A2010

agent; and he may be safely held, under certain

conditions, to be affected with knowledge that

proceedings have been instituted for its

condemnation and sale.

- Failure of the clerk to mail the notice, if in fact he

did so fail in his duty, is not such as irregularity as

amounts to a denial of due process of law; and hence

in our opinion that irregularity, if proved, would not

avoid the judgment in this case. Notice was given by

publication in a newspaper and this is the only form

of notice which the law unconditionally requires.

Midgely and Pastor, Jr. at their respective addresses

in Alicante and Barcelona.

- Both De Midgely and Pastor entered a special

appearance and filed a motion to dismiss on the

ground of lack of jurisdiction as they are nonresidents. They further alleged that earnest efforts

toward a compromise have not been made as

required in the Civil Code in suits between members

of the same family, The motion was denied by Judge

Ferandos and he ruled that the respondents were

properly summoned.

- The subsequent motion for reconsideration was

denied by Ferandos indicating in the order that the

action of Quemada was for the recovery of real

property and real rights. The respondents were

instructed to file their answer.

- De Midgely filed this action with the Supreme Court.

Prof. Victoria A.

Avena

Separate Opinion

MALCOLM; dissent

- The fundamental idea of due process of law is that

no man shall be condemned in his person or property

without notice and an opportunity of being heard in

his defense.

- "A judgment which is void upon its face, and which

requires only in inspection of the judgment roll to

demonstrate it want of vitality is a dead limb upon

the judicial tree, which should be lopped off, if the

power so to do exists. It can bear no fruit to the

plaintiff, but is a constant menace to the defendant."

DE MIDGELY VS FERANDOS

64 SCRA 23

AQUINO, May 13, 1975

NATURE

Original Actions. Certiorari and contempt.

FACTS

- Quemada, allegedly the illegitimate son of Alvaro

Pastor, Sr., was appointed as special administrator of

the latters estate by the CFI of Cebu. As such, he

filed a complaint against his half siblings, the

spouses Alvaro Pastor, Jr. and Maria Elena Achaval,

and Sofia Midgely, who were all at that time citizens

of Spain and residing in that country. The suit also

named Atlas Mining as co-respondent. The suit was

to settle the question of ownership over certain

properties and rights in some mining claims as

Quemada believed that those properties belong to

the estate of Alvaro Pastor, Sr.

- Quemada, on his own, caused extraterritorial

service of summons to be made through the

Department of Foreign Affairs and the Philippine

Embassy in Madrid, Spain, which effected the service

of the summons through registered mail upon De

ISSUE/S

WON Judge Ferandos gravely abused his discretion in

denying De Midgelys motion to dismissed based on

the lack of jurisdiction over her person.

HELD

NO. The fact that she alleged as a ground for

dismissal the lack of earnest effort to compromise is

deemed as abandonment of her special appearance

and as voluntary submission to the courts

jurisdiction.

Ratio. When the appearance is by motion for the

purpose of objecting to the jurisdiction of the court

over the person, it must be for the sole and separate

purpose of objecting to the jurisdiction of the court. If

the motion is for any other purpose than to object to

the jurisdiction of the court over his person, he

thereby submits himself to the jurisdiction of the

court,

Reasoning. Even if the lower court did not acquire

jurisdiction over De Midgely, her motion to dismiss

was properly denied because Quemadas action

against her maybe regarded as a quasi in rem

where jurisdiction over the person of a non-resident

defendant is not necessary and where the service of

summons is required only for the purpose of

complying with the requirement of due process.

Quasi in rem is an action between parties where

the direct object is to reach and dispose of property

owed by the parties or of some interest therein.

- The SC cited the Perkins case as a precedent. In

that case, it ruled that in a quasi in rem action

jurisdiction over a non resident defendant is not

essential. The service of summons by publication is

required merely to satisfy the constitutional

requirement of due process. The judgment of the

court would settle the title to the properties and to

that extent it partakes of the nature of judgment in

rem. The judgment is confined to the res (properties)

and no personal judgment could be rendered against

the non resident. It should be noted that the civil

case filed by Quemada is related to a testamentary

proceeding as it was filed for the purpose of

recovering the properties which in the understanding

of Quemada, belonged to the estate of the Late

Pastor, Sr. and which were held by De Midgely and

her brother.

Disposition. Petition is dismissed

ACQUIRED JURISDICTION OVER THE

ISSUES

SPS GONZAGA V CA (SPS ABAGAT)

SCRA

CALLEJO SR; October 18, 2004

NATURE

Petition for the Review of the Decision and resolution

of CA

FACTS

- October 22, 1991 > Sps Abagat filed complaint

against Sps Gonzaga for recovery of possession of

land in Baclaran, Paraaque issued in their names, as

owners. Sps Abagat alleged in their complaint that

they were the owners of a small hut (barong-barong)

constructed on the lot, which was then owned by the

government

- February 22, 1961 > Abagat filed an application for

sales patent over the land

- January 26, 1973 > hut was gutted by fire and after

that, Sps Gregorio built a two-storey house on the

property without their consent. Sps Abagat filed a

complaint for ejectment against Sps Gregorio but

complaint was dismissed for lack of jurisdiction

because in their answer to the complaint, the Sps

Gregorio claimed ownership over the house

- Sps Gregorio sold house to Sps Gonzaga for

P100,000 under a deed of conditional sale, in which

Sps Gregorio undertook to secure an award of the

land by the government in favor of Sps Gonzaga. In

an MOA, Sps Gregorio indicated that if they would

Civil Procedure Digest

A2010

Prof. Victoria A.

Avena

not secure such, they would return P90,000 as

payment for the house

- January 2, 1986 > Bureau of Lands granted the

application of Abagat for a sales patent over the

property.

TCT No. 128186 was issued by the

Register of Deeds in his name. Sps Abagat

demanded that Sps Gonzaga vacate the property,

but latter refused

- September 29, 1992 > Sps Abagat filed a motion

for leave to file a third-party complaint against the

Sps Gregorio. TC no longer resolved the motion for

leave to file a third-party complaint

- Trial Court > October 10, 1994, in favor of Sps

Abagat

- CA > December 19, 1997, affirmed the decision of

the trial court on. On the plea of Sps Gonzaga that

the TC should have ordered the Sps Gregorio to

refund to them the P90,000.00 the latter had

received as payment for the house, CA ruled that a

separate complaint should have been filed against

the Sps Gregorio, instead of appealing the decision of

the TC.

ISSUE

WON RTC and CA erred in not ordering Sps Gregorio

to refund to them the P90,000 they had paid for the

house and which the latter promised to do so under

their Memorandum of Agreement

HELD

NO

Ratio The rule is that a party is entitled only to such

relief consistent with and limited to that sought by

the pleadings or incidental thereto. A trial court

would be acting beyond its jurisdiction if it grants

relief to a party beyond the scope of the pleadings.

Moreover, the right of a party to recover depends,

not on the prayer, but on the scope of the pleadings,

the issues made and the law.

Reasoning

- Sps Gonzaga failed to file any pleading against Sps

Gregorio for the enforcement of the deed of

conditional sale, the deed of final and absolute sale,

and the Memorandum of Agreement executed by

them. The petitioners filed their motion for leave to

file a third-party complaint against the intervenors,

Sps Gregorio, and appended thereto their third-party

complaint for indemnity for any judgment that may

be rendered by the court against them and in favor

of the respondents. However, Sps Gonzaga did not

include in their prayer that judgment be rendered

against the third-party defendants to refund the

P90,000.00 paid by them to the Sps Gregorio. Sps

Gonzaga failed to assail the trial courts order of

denial in the appellate court. Even after the trial

court had granted leave to the Sps Gregorio to

intervene as parties-defendants and the latter filed

their Answer-in-Intervention, Sps Gonzaga failed to

file a cross-claim against the intervenors for specific

performance for the refund of the P90,000.00 they

had received from the petitioners under their deed of

conditional sale, the deed of final and absolute sale

and the memorandum of agreement and pay filing

and docket fees therefor.

Disposition Petition is DENIED DUE COURSE. CA

decision and resolution are AFFIRMED.

SPECIFIC

JURISDICTION

COURTS

A. SUPREME COURT

Question of law

OF

URBANO V CHAVEZ

183 SCRA 347

GANCAYCO; March 19, 1990

NATURE

Petition to review decision of RTC Pasig

FACTS

- there are 2 cases involved here: a criminal action

for violation of the Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices

Act (RA 3019) and an civil action for damages arising

from a felony (defamation through a published

interview whereby Chavez imputed that Nemesio Co

was a close associate (crony?) of Marcos), both

against Solicitor General Francisco Chavez (among

others)

- in the criminal case (filed in the Office of the

Ombudsman), the Office of the SolGen (OSG) entered

its appearance for Chavez and the other accused

(DILG Sec and 2 sectoral reps) as far as the Prelim

Investigation is concerned. Urbano et. al. filed a

special civil action for prohibition in the SC to enjoin

the SolGen and his associates from acting as counsel

for Chavez in the PI. The contention is in the event

that an information is filed against the accused, the

appearance of the OSG in the PI would be in conflict

with its role as the appellate counsel for the People

of the Phils (counsel at the first instance is the

provincial/ state prosecutor).

- in the action for damages, the OSG likewise acted

as counsel for Chavez, who was then the SolGen and

counsel for PCGG, the agency responsible for the

investigation of graft and corrupt practices of the

Marcoses. The OSG filed for extension of time to file

required pleading, and afterwards filed a motion to

dismiss on behalf of Chavez. Petitioner Co objected

to appearance of OSG as counsel, contending that he

is suing Chavez in his personal capacity.

- OSG manifested that it is authorized to represent

Chavez or any public official even if the said official is

sued in his personal capacity pursuant to the

unconditional provisions of PD478 which defines the

functions of OSG, as well as EO300 which made OSG

an independent agency under the Office of the

President

- RTC denied the petition, thus allowing the

appearance of OSG as counsel. It also denied the

MFR. Thus, this petition for review

ISSUE/S

1. WON the OSG has authority to appear for (a) a

certain govt official in the PI of their case before the

Ombudsman and (b) the SolGen in a suit for

damages arising from a crime

HELD

1. NO

Ratio The OSG is not authorized to represent a

public official at ANY stage of a criminal case or in a

civil suit for damages arising from a felony (applies

to all public officials and employees in the executive,

legislative and judicial branches).

Reasoning PD47811 defines the duties and

functions of OSG:

SEC1. The OSG shall represent the Govt of the Phils,

its agencies and instrumentalities and its officials and

agents in any litigation, proceeding, investigation or

matter requiring the services of a lawyer. x x x

- the OSG submits that since there is no qualification,

it can represent any public official without any

qualification or distinction in any litigation.

- Same argument seems to apply to a similar

provision in the Rev Admin Code (Sec. 1661: As

principal law officer of the Govt, the SolGen shall

have the authority to act for and represent the

Govt , its officers and agents in any official

investigation, proceeding or matter requiring the

services of a lawyer). In Anti-Graft League v Ortega,

SC interpreted Sec. 1661 to embrace PI. However,

Civil Procedure Digest

A2010

Prof. Victoria A.

10

Avena

should an info be filed after, then OSG can no longer

act as counsel. The rationale given was that public

officials are subjected to numerous suits, and threats

of criminal prosecution could stay the hand of the

public official. OSG provides assurance against

timidity in that they will be duly represented by

counsel in the PI.

- However, the court declared this ruling abandoned

in this case. The anomaly in this ruling becomes

obvious when, in the event of a judgment of

conviction, the case is brought on appeal to the

appellate courts. The OSG, as the appellate counsel

of the People, is expected to take a stand against the

accused. More often than not, it does. Accordingly,

there is a clear conflict of interest here, and one

which smacks of ethical considerations, where the

OSG, as counsel for the public official, defends the

latter in the PI, and where the same office, as

appellate counsel of the People, represents the

prosecution when the case is brought on appeal. This

anomalous

situation

could

not

have

been

contemplated and allowed by the law. It is a situation

which cannot be countenanced by the Court.

- another reason why the OSG cant represent an

accused in a crim case: the State can speak and act

only by law, whatever it says or does is lawful, and

that which is unlawful is not the word or deed of the

state. As such, a public official who is sued criminally

is actually sued in his personal capacity inasmuch as

his principal (the State) can never the author of a

wrongful act. The same applies to a suit for damages

arising from a felony, where the public official is held

accountable for his act; the state is not liable.

** Re: Question of Law (copied verbatim. This is all

that is mentioned)

-both issues raise pure questions of law inasmuch as

there are no evidentiary matters to be evaluated by

this Court. Moreover, if the only issue is whether or

not the conclusions of the trial court are in

consonance with law and jurisprudence, then the

issue is a pure question of law (Torres v Yu). Thus,

the Court resolved to consolidate both Petitions and

to treat them as Petitions for certiorari on pure

questions of law in accordance with the provisions of

the Rules of Court.

Disposition Petition is granted.

ORTIGAS V. CA

106 SCRA 121

ABAD SANTOS, 1981

NATURE

Petition for review of the decision of the CA

FACTS

-In 1974, Ortigas and Co. filed a complaint for

unlawful detainer against Maximo Belmonte in the

Municipal Court of San Juan Rizal, praying that

judgment be rendered 1.) ordering the defendant his

successors-in-interest to vacate and surrender the lot

to plaintiff; 2.) declaring the residential building

constructed on the lot by defendant as forfeited in

favor of plaintiff; 3.0 condeming defendant to pay

monthly rent of 5,000 from July 18, 1971 up to the

time he vacates, together with attorney's fees and

exemplary damages. The Ruled in favor of plaintiff

and granted the relieves prayed for.

-Belmonte filed a motion to dismiss in the Cfi based

on lack of jurisdiction on the part of the MC. CFI

denied motion and affirmed in totot the MC

judgment. The said court also issued a writ of

execution. Belmonte filed a petition for certiorari and

prohibition with preliminsry injunction in the CA,

assiling the 1.) the jurisdiction of the CFI andf MC; 2.)

the propriety of the judgment on the pleadings

rendered by the MC; and 3.) the propriety of the

issuance of the writ of execution issued by the CFI.

The Ca ruled in favor of Belmonte, holding that the

MC has no jurisdiction. Hence the present petition.

ISSUES

1. WON the CA has appellate jurisdiction over this

case

2. WON the MC had jurisdiction to resolve the issues

in the original complaint

HELD

1. NO.

Reasoning. After analyzing the issues raised by

Belmonte before the CA, namely 1.) the jurisdiction

of the CFI andf MC; 2.) the propriety of the judgment

on the pleadings rendered by the MC; and 3.) the

propriety of the issuance of the writ of execution

issued by the CFI, the SC held that the same are

purely legal in nature. Since appellate jurisdiction

over cases involving purely legal questions is

exclusively vested in the SC by Sec. 17 of the

Judiciary Act (RA 296), it is apparent that the decision

under review rendered by the CA without jurisdiction

should be set aside.

2. NO.

Reasoning. Where a subdivision owner seeks not

just to eject the lot buyer who defaulted in his

payments but also prays that the residential building

constructed by the buyer be forfeited in plaintiff's

favor, jurisdiction over the case belongs to the CFI

not the MC in an ejectment case. The issues raised

before the inferior court did not only involved the

possession of the lot but also rights and obligations

of the parties to the residential building which under

Art. 45 of the CC is real property. Aslo, plaintiff's

claim to the bldg raises question of ownership.

-A CFI cannot assume jurisdiction in a case appealed

to it under SECII Rule 40 where one of the parties

objected to its jurisdiction. Since the original case

was decided by the MC without jurisdiction over the

subject matter thereof, the CFI should have

dismissed the cases when it was brought before it on

appeal.

Disposition. Without prejudice to the right of

Ortigas to file the proper action in the proper court,

the decisions of the CA, CFI and MC of San Juan Rizal

are set aside.

JOSEFA V ZHANDONG

GR 150903

SANDOVAL-GUTIERREZ; December 8,

2003

NATURE

Petition for review on certiorari

FACTS

Tan represented himself to be the owner of

hardboards and sold them to Josefa. Josefa paid all

his obligations to Tan. The hardboards apparently

belonged to Zhandong. When Tan failed to pay

Zhandong, it sent a demand letter for the payment of

the hardboards to both Tan and Josefa.

Trial Court ruled in favor of Zhandong

The Court of Appeals affirmed the trial courts

Decision.

Petitioner filed a motion for reconsideration but was

denied.

Petitioner ascribes to the CA the error in affirming

the ruling of the trial court that Josefa is liabe to

Zhandong despite THE MOUNTAIN OF EVIDENCE

showing that they had no business transaction with

each other and that it was Tan who was solely

responsible to Zhandong for the payment of the

goods.

Civil Procedure Digest

A2010

Prof. Victoria A.

11

Avena

ISSUE

1. WON Josefa is liable to Zhandong for the payment

of the merchandise

HELD

1. NO

Reasoning. Evidence indicate that Tan bought the

hardboards from Zhandong and, in turn, sold them to

petitioner. However, both the trial court and the

Court of Appeals ignored this glaring reality and

instead held that petitioner purchased the boards

directly from respondent.

General Rule : Only questions of law may be

entertained by the Supreme Court in a petition for

review on certiorari

Exceptions:

(1) the conclusion is grounded on speculations,

surmises or conjectures;

(2) the inference is manifestly mistaken, absurd or

impossible;

(3) there is grave abuse of discretion;

(4) the judgment is based on a misapprehension of

facts;

(5) the findings of fact are conflicting;

(6) there is no citation of specific evidence on which

the factual findings are based;

(7) the finding of absence of facts is contradicted by

the presence of evidence on record;

(8) the findings of the Court of Appeals are contrary

to those of the trial court;

(9) the Court of Appeals manifestly overlooked

certain relevant and undisputed facts that, if properly

considered, would justify a different conclusion;

(10) the findings of the Court of Appeals are beyond

the issues of the case;

(11) such findings are contrary to the admissions of

both parties.

Disposition Petition is granted.

Petition for certiorari3

FACTS

-September 15, 1980: acting on the evidence

presented by the Philippine Constabulary

commander at Hinigaran, Negros Occidental, the CFI

of that province issued a search warrant for the

search and seizure of the deceased bodies of seven

persons believed in the possession of the accused

MAYOR Pablo Sola in his hacienda at Sta. Isabel,

Kabankalan, Negros Occidental.

-September 16, 1980: armed with warrant,

elements of the 332nd PC/INP Company proceeded

to the place of Sola. Diggings made in a canefield

yielded two common graves containing the bodies of

Fernando Fernandez, Mateo Olimpos, Alfredo Perez,

Custodio Juanica, Arsolo Juanica, Rollie Callet and

Bienvenido Emperado.

-September 23 and October 1, 1980: the PC

provincial commander of Negros Occidental filed

seven (7) separate complaints for murder against the

accused Pablo Sola, Francisco Garcia, Ricardo Garcia,

Jose Bethoven Cabral, Florendo Baliscao and fourteen

(14) other persons of unknown names. After due

preliminary examination of the complainant's

witnesses and his other evidence, the municipal

court found probable cause against the accused. It

thus issued an order for their arrest.

-However, without giving the prosecution the

opportunity to prove that the evidence of guilt of the

accused is strong, the court granted them the right

to post bail for their temporary release. The accused

Pablo Sola, Francisco Garcia, and Jose Bethoven

3 The one who filed this appeal which partakes of a nature of certiorari are private

prosecutors Francisco Cruz and Renecio Espiritu. The assertion of the petitioner private

prosecutors is that they are instituting the action `subject to the control and supervision of

the Fiscal. (CJ Fernandos prefatory statement states that the two have no legal standing to

raise this petition. Since Sol Gen Mendoza never bothered to question their legal standing,

the Court contented itself with the fact that the Solicitor General has authority to raise this

Change of venue

PEOPLE v. MAYOR PABLO SOLA

103 SCRA 393 (1981)

FERNANDO, C.J.

NATURE

petition in behalf of the People of the Philippines)

The Solicitor General adopted a two-pronged thrusts in this petition: 1. the setting aside, by

certiorari, of the order of the Municipal Court of Kabankalan, presided over by Judge Rafael

Gasataya, granting bail to the accused in the criminal cases mentioned above, and 2. the

petition for a change of venue or place of trial of the same criminal cases to avoid a

miscarriage of justice."

Cabral availed themselves of this right and have

since been released from detention.

-In a parallel development, the witnesses in the

murder cases informed the prosecution of their fears

that if the trial is held at the Court of First Instance

branch in Himamaylan which is but 10 kilometers

from Kabankalan, their safety could be jeopardized.

At least two of the accused are officials with power

and influence in Kabankalan and they have been

released on bail. In addition, most of the accused

remained at large. Indeed, there have been reports

made to police authorities of threats made on the

families of the witnesses." The facts alleged argue

strongly for the remedies sought, namely a change of

venue and the cancellation of the bail bonds.

-March 15, 1981: this Court issued the following

resolution: "The Court Resolved to: (A) [Note] the

comment of the Solicitor General on the urgent

petition for change of venue and cancellation of bail

bonds, adopting the plea of the petition, namely, (1)

the setting aside, by certiorari, of the order of the

Municipal Court of Kabankalan, presided over by

Judge Rafael Gasataya, granting bail to the accused

(2) the petition for a change of venue or place of trial

of the same criminal cases to avoid a miscarriage of

justice;

(B) [Transfer] the venue of the aforesaid criminal

cases to Branch V of the Court of First Instance of

Negros Occidental at Bacolod City, presided by

Executive Judge Alfonso Baguio, considering that

District Judge Ostervaldo Emilia of the Court of First

Instance, Negros Occidental, Branch VI at

Himamaylan has an approved leave of absence

covering the period from January 12 to March 12,

1981 due to a mild attack of cerebral thrombosis and

that the said Branch V is the nearest court station to

Himamaylan; and

(C) [Await] the comment of respondents on the

petition to cancel bail, without prejudice to the public