Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Time Management For Students: Revised Edition, 2003, Counselling and Development Centre, York University

Time Management For Students: Revised Edition, 2003, Counselling and Development Centre, York University

Uploaded by

Hisham MohammedOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Time Management For Students: Revised Edition, 2003, Counselling and Development Centre, York University

Time Management For Students: Revised Edition, 2003, Counselling and Development Centre, York University

Uploaded by

Hisham MohammedCopyright:

Available Formats

Time Management for Students

Revised Edition, 2003, Counselling and Development Centre, York University

Brian Poser, B.A., M.Ed., Learning Skills Counsellor,

York University.

www.yorku.ca/cdc/lsp

You need to manage time effectively if youre going to be successful. All other things

being held constant, better time management skills can improve your grades, help you

keep stress in check, and help you be competitive in the career you undertake following

your university education (Gortner, Lahmers, and Zulaut, 2000; Macan et. al., 1990; ISR,

1995). The purpose of this document is to teach you how to manage your time to improve

your academic and personal performance. It refers to research on academic selfregulation research and discusses time management strategies to help you adjust how you

think about time, improve your awareness of how you use time, and make change for

peak performance.

The Time Management Cycle

Time management systems often fail because they are born of perfectionism and

unrealistic expectations. For instance, some people dont initiate a time management

approach until theyre already falling behind in their work; they undertake time

management as a means of catching up. Their initial plans tend to cram in everything

they have to do without appropriate regard for the time required. The unrealistic plans

that emerge from catch-up time management amount to little more than an expression

of renewed motivation for change but without the structure to support it. Those trying to

follow crammed schedules often fall seriously behind their intended pace and abandon

the plan altogether, resulting in continued time trouble. Some conclude somehow that

these strategies of planning dont work for them. But, what is important isnt being

perfect, it is making and using a plan that helps you accomplish your goals.

One of your best options for time management systems is to begin using a cyclical

system early in the academic year. Usually the system begins with the process of goal

setting to establish a context for managing time. The next phase of the system involves

tracking time and developing an awareness for where you spend your time. The third

phase of the cycle is plan making, and this could include making to-do lists, weekly

plans, monthly plans and longer-range plans. The fourth phase of the system is selfmonitoring your action. Self monitoring involves paying attention to how well you are

working your plan, how accurately you ha ve planned, how well you have forecasted for

various events and so on. The ideas for self- monitoring come from important research on

student academic self-regulation which emphasizes the importance of adaptation in

student success (see Zimmerman, 1998; Butler, 1998, and Boekarts, 1995). The final

phase of the cycle is time shifting and adjusting (i.e., changing where you spend your

Brian Poser, B.A., M.Ed., Learning Skills Counsellor, York University. www.yorku.ca/cdc/lsp

2003, Counselling and Development Centre, York University

time to better match your intended use of time) in which you make corrections to the

system before starting the cycle again at goal setting. Taken together, these phases permit

you to initialize a process of gradual, performance-based improvement in time

management skill. Everybody wants the quick fix, but the complexity of changes

involved in really getting a grip on your time management process will take some time to

move through. Resist the urge to cast aside strategies that dont promise instant results;

like it or not, change takes time.

Goal Setting

What are your goals? Really, what are your goals? It might help to divide your goals into

time frames (immediate goals, short-mid-term goals, long-range goals) but you dont

absolutely have to do so for the exercise to be useful. And, you dont have to have firm

answers to those gripping questions about what you want to be or do when youre done at

university to make this work; your goals are likely to shift and change over time anyway.

All you need to do right now is think of a handful of goals to get started. Write down a

list of goals now before reading further.

Take a look at your list of goals. How many of the tasks you intend to do today contribute

to accomplishing the goals you have set for yourself? Are you actively working on these

goals? Are you putting any of them off for a later time? What would you have to change

in your life to make it possible to work on these goals?

Sub-dividing Goals into manageable pieces

Once you have a set of goals, it is useful to decompose the goals into manageable steps or

sub- goals. Decomposing your goals makes it possible to tackle the m one small step at a

time and to reduce procrastination. Consider for instance the goal of obtaining your

degree. This goal can be broken down into four sub-goals. Each sub- goal is the

successful completion of one year of your program. These sub- goals can be further

broken down into individual courses within each year. The courses can be broken down

into tests, exams, term papers and such within the course, or into the 13 weeks of classes

in each term. Each week can be further subdivided into days, and each day can be thought

of in terms of the hours and minutes youll spend in your classes and doing homework for

today. While it may seem challenging to take in the whole scope of that convergent goal,

thinking of your goals in this way helps to reinforce the idea that there is a connected

path linking what actions you take today and the successful completion of your goals.

Seeing these connections can help you monitor your own progress and detect whether

you are on track or not. Take some time now to think through the goals youve set and to

break them down into their smaller constituent parts.

Time Awareness and Time Tracking

It will help you manage your time well if you know where your time actually gets spent.

One very helpful way of determining your actual usage of time is to track your time. The

process here is like making a schedule, but it works in reverse. Instead of writing things

in that you are planning to do, time logging is a process of writing down the things that

you have already done. Doing this is sort of a get-to-know-yourself exercise because this

procedure will highlight many of your habits that you might selectively ignore currently.

Brian Poser, B.A., M.Ed., Learning Skills Counsellor, York University. www.yorku.ca/cdc/lsp

2003, Counselling and Development Centre, York University

For instance, some people find that every time they plan to do math homework they end

up watching television. Other people just cant seem to follow their schedule until the

week before finals. Whatever your time habits, time tracking will help you adjust and

fine-tune your time management practices. Having accurate information about your time

usage patterns can serve as another important point of reference for self- monitoring. A

few ways to track your time follow:

Strategy #1: Time Tracking is fairly straightforward. At the end of every hour jot

yourself a quick note about how you actually spent your time for that hour. The note

neednt be long; one sentence or less should suffice. If how you spent your time doesnt

match an already planned activity, simply enter a comment as to what you really did

during that time. This way you will be able to review patterns that emerge in your use of

time and make adjustments to improve your productivity.

Strategy #2: Some people find it helpful to modify the planning page to facilitate

tracking time. The modifications are easy enough: make two columns on your paper for

each day of the week. In one column, write down the plan you are trying to follow; in the

second column, make notes on what you actually did with your time. The side-by-side

comparison is very telling and an excellent way to figure our where youre not using time

in the way you intend.

Strategy #3: Another effective way to make changes and get results from your time

management strategies is to summarize your time use by time category such as: sleep,

study, work, travel and so on. Before doing the summary, estimate the amount of time

that you think you spend on the various activities listed on the form below and enter these

in the expected row of the summary sheet. Feel free to add any additional categories

that might be helpful. Then log your time for one week on an hour by hour basis. When

the week is over summarize your time by category for each day, add up the values for all

seven days of the week, and write the totals in the actual row of the summary sheet.

Summarizing your time

use allows you to

understand how much time

you really spend in the

various areas of your life.

Take a look at the example

form to the right; it is a

sample that we have used

in many workshops with

students. It is almost

certain that you will see a

notable difference between

the number of hours you

expected to use in certain

categories and the actual

number of hours you

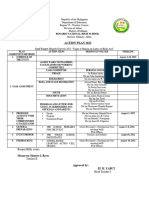

Weekly Summary of Time Use

Sleep

Eating Commute

Family/

Social

Study

Work

Monday

Tuesday

Wednesday

Thursday

Friday

Saturday

Sunday

Expected

Actual

Difference

Brian Poser, B.A., M.Ed., Learning Skills Counsellor, York University. www.yorku.ca/cdc/lsp

2003, Counselling and Development Centre, York University

T.V.

Other

spend. If you find that you spend more time in one area than you wanted, and less in

another, the weekly summary of time use clearly indicates which activities to reduce to

find the extra time you want for that neglected area of your life.

However you choose to understand the differences between your expected use of time

and your actual use of time, your focus should be on trying to detect and adjust patterns

in your own real use of time that spell trouble for you reaching your goals. (For those of

you freaked out by knowing exactly where you spend your time because it only seems to

reinforce your sense of time pressure, read chapter 15 of Ralph Keyes book Timelock:

How life got so hectic and what you can do about it. )

Heres something to think about: Various published resources and informal studies report

that, in Canada and the United States, fully half of the 168 hours available in a week (that

is, on average 84 of those hours) are used up for the basics, including sleeping, eating,

washing and beautifying, and commuting from home to school and to work. (Robinson

and Godbey, 1997) How do your own numbers compare? How will you spend the

remaining 84 hours per week?

Planning

You have probably used various kinds of planning tools before, including a daily or

weekly planner, a month-at-a-glance planner, and so on. In this section, we introduce four

planning tools and the thinking strategies that go along with each one: a Monthly Planner,

a Weekly Objectives List, a Weekly Planner and a Time Log. It is important to keep in

mind that the purpose of scheduling is not to enslave you to your planner, but rather to

record your decisions about when certain things should happen.

The Monthly Planner

The monthly planner can be used as a time-bound memory aid, tracking major deadlines

and exam dates, appointments, important anniversaries, birthdays, holidays, vacations

and so on. But, you can get more out of the monthly planner if you use it to record

interim deadlines and forecast upcoming busy periods as final deadlines approach. A

properly completed monthly planner will indicate upcoming busy periods, show whether

there is room in the plan for new tasks, and help you assess whether you are on target to

achieve your goals. Lets say for example that you had an upcoming exam in your

Introductory Microeconomics class. Start by entering the date of the exam so you dont

forget it. Next, think of the tasks that comprise the goal of doing well in the exam, think

about how long each step of the task should take, and enter a series of interim deadlines

for each step between the start of your preparation for the exam and the exam date itself.

Use these interim deadlines as milestones to indicate the progress of your study. (If

youre prone to breaking your own interim deadlines, it can help to reinforce these by

making appointments with a peer, an instructor, or a teaching assistant.)

Brian Poser, B.A., M.Ed., Learning Skills Counsellor, York University. www.yorku.ca/cdc/lsp

2003, Counselling and Development Centre, York University

Weekly Objectives List

If your current approach to time management is governed by to-do lists, then youll be

interested in the weekly objectives list. Think of the weekly objectives list as a musclebound to-do list. In essence, the weekly objective list is a to-do list with additional

features to further decompose tasks into smaller units and to record time estimates for the

task. Lets say for example that one of your goals for the year was to maintain your

honours standing and that you had a series of exams coming up including one for first

year Introductory Microeconomics (see below). You might set an objective to score a B+

or A grade on the exam and list this on your objectives list. Your next step would then be

to consider a variety of study activities that would prepare you well for the examination.

You might begin by entering your first activity, complete readings and review lecture

notes, in the activities column. Once you have entered your activity it is important to

assign it a time estimate, in this case weve assigned this activity a three hour block of

time. This block of time reflects an important principle in time estimating; when

estimating time you might want to add time to the amount of time you think it will take

you to complete the task. Try applying a factor of 1.5 to 2.0 to the estimate and refine

your estimates from there on the basis of your experience with similar tasks. This is

important because we tend to estimate without considering possible difficulties or

interruptions. Once you have entered the first activity for study, you would continue with

the others you have in mind. The final two columns on the form allow you to track

whether or not you have scheduled and completed the activities you have listed. Your

next step is to carry the listed activities, along with their associated time estimates, to

your weekly planner to be scheduled.

Weekly Objectives List

Academic Objective

Score B+ or higher on

Economics Exam

Activity

150%-200%

Time Estimate Scheduled

complete readings/review notes

3 hrs

select main concepts

1 hr

practice problems from chapter

2 hrs

reproduce graphs from memory

1 hr

paragraphs to interpret graphs

1 hr

Completed

Brian Poser, B.A., M.Ed., Learning Skills Counsellor, York University. www.yorku.ca/cdc/lsp

2003, Counselling and Development Centre, York University

The Weekly Planner

Take a look at your weekly planner. What do you have written in it? Likely, you list

lecture times, tutorial times, laboratory times, times for extracurricular activities, and

various other appointments. If this sounds like your schedule then you are probably

under- using another very versatile time management tool because many of the most

important tasks (homework activities which move you toward your goals) are left out of

the picture. The implication of this should be clear: If it isnt on the schedule it wont

get done.

Stepping from the weekly objectives list to the weekly planner is easy. Using the time

estimates for the activities on the weekly objectives list as guides find a block of time of

appropriate duration in your schedule. Then write in the activities one at a time in

priority order until you have either scheduled all of your activities or you have run out of

time spaces. A good idea here, if it seems youll run out of time spaces, is to start

scheduling the most important activities first. For instance, consider the following

activity: Complete readings and review notes. This activity might take 3 hours and

could be placed almost anywhere in the week where you have time and where youll

likely be able to work. You might schedule three one-hour blocks, two 90 minute blocks

or one three- hour block, depending on your preferences. The key here is to associate the

specific task to specific times, avoiding making a schedule where the tasks are too closely

scheduled or where important activities are assigned to unrealistic work times.

Construct a plan for each week, following the rhythm of your courses that meet weekly.

To help make planning a routine activity, pick a regular day each week to schedule. Even

with unexpected occurrences that can impact your schedule you assist yourself in making

decisions that are governed by your desire to reach your goals. Without using a schedule

you may be governed by your moment-to- moment moods which may lead you to make

time decisions that take you away from your goals. Once your week is planned you will

experience clarity of focus, your tendency to be distracted will be reduced and you will

be certain of your reasons for doing the things you had planned. Committing yourself to

a plan youve made represents a renewal of your motivation for the goals and tends to

increase your time on task.

How much time is enough?

The time you spend on task has some relationship to the quality of work you end up

producing. A good gauge to follow is to perform 2-3 hours of school work outside class

for every hour of class time. Yes, this means for a full-time student with a 15 hour of

class per week load the recommendation is to do between 30 and 45 hours of homework

each week. Yes, thats a big jump, especially if you breezed through high school or

previous years of university on less. This estimate simply reflects the time it actually

takes to learn effectively at university (ISR, 1995a; ISR, 1995b). But this number

shouldnt mean that you completely forego time for yourself. It is important to have some

personal time. Even though you may work a part-time job (and doing so isnt necessarily

counter-productive to success at school (ISR, 1995d)), youll need to take some time for

yourself and for recreation each week. A starting guideline might be something like 10%

of your week, or 17 hours. What is more important than these specific targets is that you

Brian Poser, B.A., M.Ed., Learning Skills Counsellor, York University. www.yorku.ca/cdc/lsp

2003, Counselling and Development Centre, York University

spend enough time on school work to ensure that youre successful and that you spend

enough time outside of school to ensure that you have a healthy balance in your life.

Keep in mind that using a planner in the way were describing is a learned skill that will

take time and patience to master. Keep your focus not on making the perfect plan or on

executing every plan flawlessly, but on learning from your good and bad experiences and

using this knowledge to improve subsequent plans.

Taking Action

Once you have set your goals, figured out where your time is currently spent and decided

on a plan that will help you to reach your goals, the next step is to take action. Now you

must do the tasks that converge on your goals. By producing a plan, you have written

down your decisions about how to spend your time so that you dont have to get stuck

deciding whether to do tasks that have nothing to do with your goals. As you begin

working on the tasks, keep your focus on doing the best you can to execute what you

have set out for yourself. Stay very clear on the fact that the plan is an ideal and that in

action you will not execute it perfectly. Some things will take longer than you planned.

Some new tasks will emerge. There will be enticing distractions that may take your

attention away from your work, but you can diminish the impact of distractions if you

remember that the tasks listed on your plan lead you to goals you have chosen for

yourself. The main thing is to do the very best you can to follow the plan and monitor

your progress so that you can learn from your good and bad experiences along the way.

Time Shifting and Adjusting

Inevitably, you will need to make adjustments to your plans and your time management

habits. As you encounter time troubles, keep in mind that some are predictable, some are

not; some are controllable, some are not. For those that are not controllable, keep your

cool and get back on track as soon as possible. For time troubles that you can control, and

particularly those that occur predictably, deal with them directly and forcefully so that

they dont prevent you from achieving your goals. Examine the following list of

troubles: the tips and strategies associated with each one can help you shift your time

back to your goals.

Procrastination

Youre not alone. According to OBrien (2002) up to 40% of university students

experience procrastination as a problem. Also, Taraban et. al. (1999) reported that

students tended to mass their practice (that is, do most of the work in marathon sessions)

near academic deadlines and failed to make appropriate use of various study aids and

supports at appropriate times (i.e., earlier in the term). But why do you procrastinate on

tasks related to goals you want to achieve? Burka and Yuen (1983) argue that

procrastination often emerges as a means of distancing oneself from stressful activities.

For instance, Son and Metcalf (2000) report people allocate more time to the judged-easy

task than to judged-difficult tasks. Burka and Yuen (1983) indicate that dealing with the

underlying stressful aspects of the activities can assist in reducing the extent of

procrastination. Heres one practical application. If youre overwhelmed by the volume

Brian Poser, B.A., M.Ed., Learning Skills Counsellor, York University. www.yorku.ca/cdc/lsp

2003, Counselling and Development Centre, York University

of work on your to-do list, you might benefit from making a one- item list: re-write the

top item from your list at the top of a blank page and work the task to completion, then

repeat.

Getting Started

It can be difficult to start working. Most of the time, however, not starting seems to be

related to fear of poor results or negative evaluations than it is to the actual difficulty of

the work. Aim to subdivide tasks into small steps and convince yourself that to get started

all you need is 10 full minutes working on a task. Often, the 10 minutes will elapse and

youll be right into the swing of things, prepared to continue on productively.

Motivation

Sometimes you just dont feel motivated to do your school work. It might help to realize

that for many people motivation isnt a prerequisite to actionit is a result of it! Try

working for a short time and see if you can get into it. If your motivation problem

seems more substantial, it might help to realize that when you arent motivated to do

school work, you arent actually out of motivationyoure just motivated to do

something else.

Line-ups

Youll spend a lot of your time waiting in lines. At the library check-out, waiting for the

bus, waiting for the light to turn green at an intersection, buying tickets, and even waiting

for the professor to arrive at class you find yourself just waiting. If you carried around

a book or some photocopied readings you could be actively using time that would

otherwise escape you. Tape cassettes of your lectures are ideal ways to fill times like

these, and the review will profoundly aid your recall come exam time.

Commuting

North Americans spend between 1 and 2 hours commuting from home to work or school

every day. If you commute, you will probably find 5 to 10 hours of your week taken up

in a car, bus or subway. In one year, your commute works out to between 250 and 500

hours; over the course of 4 or 5 years, your commuting time equates to attending all of

the required lectures in every course of a 4-year university degree. The challenge is to

use that time for something productive. One common example is to read on the bus or

subway. Even 5 minutes and a couple of pages work out to hours and books. If you

happen to be driving, dont read - thats dangerous. But, study anyway. Tape your

professors lecture or yourself reading. You will be amazed at how much you can learn

in these small blocks of time. The key to commuting time is, simply, use it or lose it.

Between Classes

Take a look at your lecture schedule. Do you have a couple 1-hour or 2-hour blocks of

time between classes? What are you doing with that time? Dont excuse wasted time with

the worn out justification that you had only one or two hours and couldnt really get into

anything. Do something useful with the time. To make the most of the time between

classes, find a spot on campus where you can work comfortably and without interruption.

And remember, not every minute of time needs to go to school work..

Brian Poser, B.A., M.Ed., Learning Skills Counsellor, York University. www.yorku.ca/cdc/lsp

2003, Counselling and Development Centre, York University

Conclusion: Repeating the Time Management Cycle

We began this article by introducing the idea of the time management cycle.

Accordingly, we end this article where we began by reminding yo u that the time

management cycle is meant to be an iterative process. As you go through the cycle

multiple times, youll find that your goals solidify, your awareness of your time use

sharpens, and your ability to make a workable plan improves. As you take action on your

plans in successive cycles of time management, you will gain academic confidence from

knowing that you are progressing towards your goals. As you face the day to day realities

of student life, you will need to remain flexible and willing to learn from your

experiences and to adjust your plans as they unfold. Remember that the goal is always to

build on what you have learned from before. Time management is not only a school

skill; indeed, time management and self- management are life skills that will figure

largely in your future success. Good luck and best wishes.

References

Boekaerts, M. (1995). Self-regulated learning: Bridging the gap between metacognitive

and metamotivation theories. Educational Psychologist. 30(4), 195-200.

Burka, J. B. & Yuen, L. M. (1983). Procrastination: Why You Do It and What to Do

About It. Reading, Massachussetts: Addison-Wesley.

Butler, D. L. (1998). A strategic content learning approach to promoting self-regulated

learning in students with learning disabilities. In Schunk, D. H. & Zimmerman, B. J.

(Eds.), Self-regulated learning: From teaching to self-reflective practice (pp. 160-183).

New York: Guilford Publications, Inc.

Gortner-Lahmers, A., & Zulauf, C.R. (2000). Factors associated with academic time use

and academic performance of college students: A recursive approach. Journal of College

Student Development . 41(5), 544-556.

Institute for Social Research (ISR) Centre for Research in Higher Education. (1995a).

Getting Good Grades in First Year. York Student Experience Study.

Institute for Social Research (ISR) Centre for Research in Higher Education. (1995b).

Study Habits of First-Year Students: Bulletin #9. York Student Experience Study.

Institute for Social Research (ISR) Centre for Research in Higher Education. (1995c).

Hours of Study and Marks of First-Year Students: Bulletin #10. York Student Experience

Study.

Brian Poser, B.A., M.Ed., Learning Skills Counsellor, York University. www.yorku.ca/cdc/lsp

2003, Counselling and Development Centre, York University

10

Institute for Social Research (ISR) Centre for Research in Higher Education. (1995d).

First-Year Students Who Work: Bulletin #7. York Student Experience Study.

Keyes, R. (1991). Timelock: how life got so hectic and what you can do about it. New

York: Harper Collins Publishers.

OBrien, W.K. (2002). Applying the transtheoretical model to academic procrastination.

Dissertation Abstracts International. Section B: The Sciences and Engineering. 62(11-B):

5359.

Robinson, J., & Godbey, G. (1997). Time for life : the surprising ways Americans use

their time. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Son, L.K., & Metcalfe, J. (2000). Metacognitive and control strategies in study-time

allocation. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition.

26(1), 204-221.

Taraban, R., Maki, W.S., & Rynearson, K. (1999). Measuring study time distributions:

Implications for designing computer-based courses. Behavior Research Methods,

Instruments and Computers. 31(2), 263-269.

Zimmerman, B. J. (1998). Developing self- fulfilling cycles of academic regulation: An

analysis of exemplary instructional models. In Schunk, D. H. & Zimmerman, B. J. (Eds.),

Self-regulated learning: From teaching to self-reflective practice (pp. 1-19). New York:

Guilford Publications, Inc.

Brian Poser, B.A., M.Ed., Learning Skills Counsellor, York University. www.yorku.ca/cdc/lsp

2003, Counselling and Development Centre, York University

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5813)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (844)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Rail Method of Measurement 2 Detailed MeasurementDocument106 pagesRail Method of Measurement 2 Detailed MeasurementKlarens MishoNo ratings yet

- Introvert Extrovert QuestionnaireDocument2 pagesIntrovert Extrovert QuestionnaireJustin Oliver Hautea67% (3)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- 003 - Option B Chapter 14 Engineering Physics PDFDocument62 pages003 - Option B Chapter 14 Engineering Physics PDFyuke kristinaNo ratings yet

- Action Plan - Brigada Eskwela 2022Document1 pageAction Plan - Brigada Eskwela 2022Anna Lou R. retubaNo ratings yet

- Solving Parts of A Triangle Using Circular FunctionDocument17 pagesSolving Parts of A Triangle Using Circular FunctionJisa PagodnasomuchNo ratings yet

- Orifice Plate Calculator Pressure Drop CalculationDocument6 pagesOrifice Plate Calculator Pressure Drop Calculationlutfi awnNo ratings yet

- Concept Paper TemplateDocument6 pagesConcept Paper TemplateHartaj Singh Makol100% (1)

- MECH448 Chapter7 2011Document11 pagesMECH448 Chapter7 2011mgskumarNo ratings yet

- GS49521 - Individual Assignment - Data Analysis Annual VKTDocument29 pagesGS49521 - Individual Assignment - Data Analysis Annual VKTIlyas H. AliNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Gang Violence EssayDocument4 pagesThe Effects of Gang Violence Essayapi-247028342No ratings yet

- Product Design and Development PDFDocument3 pagesProduct Design and Development PDFAbdullahNo ratings yet

- Term Dates Look@My Work AssemblyDocument6 pagesTerm Dates Look@My Work AssemblyTockington Manor SchoolNo ratings yet

- The NEFA Foundation - The North Carolina Jihad Cell and The Quantico Marine Base PlotDocument53 pagesThe NEFA Foundation - The North Carolina Jihad Cell and The Quantico Marine Base PlotDrift0242No ratings yet

- Gaudya Vaishnava Calendar 2024-2025Document10 pagesGaudya Vaishnava Calendar 2024-2025Gerardo Hernandez ArenasNo ratings yet

- Business Process ModelingDocument24 pagesBusiness Process ModelingSatish987No ratings yet

- Industry and Competitor Analysis: Bruce R. Barringer R. Duane IrelandDocument49 pagesIndustry and Competitor Analysis: Bruce R. Barringer R. Duane IrelandfaizaNo ratings yet

- Bookshoppe Jan 2013Document23 pagesBookshoppe Jan 2013ibnusina2013No ratings yet

- 03 Planificare - Semestriala - Optional - Successful - WritingDocument2 pages03 Planificare - Semestriala - Optional - Successful - Writingelena smithNo ratings yet

- Chapt 13 RevDocument6 pagesChapt 13 RevJNo ratings yet

- Five Suns: LegendDocument5 pagesFive Suns: LegendJames FranklinNo ratings yet

- Japan's Foreign PolicyDocument18 pagesJapan's Foreign PolicyJustina KiNo ratings yet

- Metrics: Q: What Is Metric?Document16 pagesMetrics: Q: What Is Metric?gau_1119No ratings yet

- Voidable ContractDocument12 pagesVoidable Contractblisterring_guy100% (4)

- Fuzzy Logic: Dr. Umang Soni NsutDocument28 pagesFuzzy Logic: Dr. Umang Soni NsutParth AgarwalNo ratings yet

- QUEEN's PROCLAMATION ACT OF BETTER GOVERNANCEDocument2 pagesQUEEN's PROCLAMATION ACT OF BETTER GOVERNANCERiddhi ChaumwalNo ratings yet

- Audit 1Document25 pagesAudit 1Mohammad Saadman100% (1)

- Rainfll Measure VoterDocument15 pagesRainfll Measure VoterngaNo ratings yet

- Cursul II Jean-Ovide Decroly - CareerDocument5 pagesCursul II Jean-Ovide Decroly - CareerTimea UrdaNo ratings yet

- Kinematics FormulasDocument20 pagesKinematics Formulasapi-285179261100% (1)