100%(10)100% found this document useful (10 votes)

5K views240 pagesVisual Language For Designers

Within every picture is a hidden language that conveys a message, whether it is intended or not. This language is based on the ways people perceive and process visual information. By understanding visual language as the interface between a graphic and a viewer, designers and illustrators can learn to inform with accuracy and power.

Uploaded by

AlekseyCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online on Scribd

100%(10)100% found this document useful (10 votes)

5K views240 pagesVisual Language For Designers

Within every picture is a hidden language that conveys a message, whether it is intended or not. This language is based on the ways people perceive and process visual information. By understanding visual language as the interface between a graphic and a viewer, designers and illustrators can learn to inform with accuracy and power.

Uploaded by

AlekseyCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online on Scribd

tuodxoow

PRINCIPLES FOR

| CREATING GRAPHICS THAT

i— i PEOPLE UNDERSTAND

FOR DESIGNERS

PRINCIPLES FOR

CREATING GRAPHICS THAT

PEOPLE UNDERSTAND

CONNIE MALAMED

suodxo0u

‘© 2009, 2011 by Rockport Publishers, Inc. and Connie Malamed

{All rights reserved. No part ofthis book may be reproduced in any form without

‘ten permission ofthe copyright owners. All images in this book have been

reproduced with the knowledge and prior consent ofthe artists concerned, and no

responsibly is accepted by producer, uber, or printer for any infringement of

Copyright or otherwise, arising from the contents of this publication. Every effort has

been made to ensue that credits accurately comply with information supplied. We

‘apologize for any inaccuracies that may have occurted and will resolve inaccurate

(or missing information in a subsequent reprinting ofthe book.

First published in the United States of America by

Rockport Publishers, a member of

(Quayside Publishing Group

100 Cummings Center

Suite 406-1

Bevery, Massachusetts 01915-6101

Telephone: (978) 282-9590,

Fax: (978) 283.2742

ver tockpub.com

Digtal edtion: 978-1-61673-619-4

Softcover edition: 978-1-59253-516-6

lication Data

Library of Congress Cataloging

Malamed, Connie.

Visual language for designers : principles for creating graphics that people under-

stand / Connie Malames.

pcm,

ISBN-13: 978-1.59253-515-6

ISBN-10; 1-59253-515-1

1. Commercial art. 2. Graphic ats 3. Visual communication. |. Tile.

1NC997.§24 2009

741.601'9-de22

2008052335

Cs

ISBN-13: 978-1-59253-515-6

ISBN-10: 1-59253-515-1

10987654321

Design: Kathie Alexander

Printed in Singapore

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

My heartfelt thanks to the designers around the globe

who contributed their exceptional work to this book

and to all the professors and researchers who happily

answered my stream of questions. Thanks to everyone

at Rockport Publishers for their dedication and

hard work.

4 Visual Language for Designers

DEDICATION

To Tom for untiring support,

Hannah for invaluable help,

and Rebecca and Silas for sweet encouragement.

R58

XXX

Pils 33 as

Ee

Pea

dE

= eo 7 /, = a

vv

ae Bie

=

SECTION ONE

SECTION TWO

1

Introduction .

GETTING GRAPHICS

{An explanation of haw we process

visual information 19

PRINCIPLES

Organize for Perception

Features that Pop Out

Texture Segregation

Grouping

Direct the Eyes .

Postion

Emphasis

Movement

Eye Gaze

Visual Cues

Reduce Realism

Visual Noise

Sihouettes

leonie Forms

Line Act

Quantity

228

29

230

235

ography

Glossary of Terms .

Sources Cited

Directory of Contributors

4 Make the Abstract Concrete

Big Picture Views 40

Data Displays 1a

Visualization of Information 150

More than Geography 156

Snapshots of Time 162

5 Clarify Complexity 168

Seginents and Sequences 178

Specialized Views tas

Inherent Structure 196

© Charge i Up .. 203

Emotional Saienee 210

Narratives 214

Visual Metaphors 220

Novelty and Humor 224

a

9900 HOHHHHHHOOY

9900 HHHHVOYD

9900 HHHHHHOOYD

9900 HHHHOOYD

9900 HHHHDOYD

00000 HHHOOOY

9900 HOHHHHHHVOY

9900 HHHHHHOOY

9900 HHHHDOYD

9900 HHHHHHVOD

0900 HHHHVOY

9900 HHHHHHOOD

0900 HHHHOOY

09000 HHHHOHOY

8 Visual Language for Designers

INTRODUCTION

“Sight is swift, comprehensive, simultaneously analytic, and synthetic. It requires so

little energy to function, as it does, at the speed of light, that it permits our minds to

receive and hold an infinite number of items of information in a fraction of a second.”

In the begining was the dot

‘Mazi Zand,

1M. Zand Studio, an

‘WE HAVE No CHOICE but to be drawn ta images.

ur brains are beautifully wired for the visual exper

tence. For thase with intact visual systems, vision Is the

dominant sense for acquiting perceptual information,

We have over ane millon nerve fibers sending signals

‘om the eye tothe brain, and an estimated 20 bilion

reutons analyzing and integrating wsual information

‘at rapid speed. We have a surprisingly large capacity

for picture memory, and can remember thousands of

Images with few errors?

We are also compelled to understand images. Upon

viewing a visual, we immediately ask, “Whats 1?" and

What does it mean?” Our minds need to make sense

ofthe world, and we do so actively To understand

something isto scan and search our memary stores,

to call forth associations and emotions, and to use

what we already know ta interpret and laf meaning

CALEB GATTENGO, Towra Vivo Cut

on the unknown. As we derive pleasure, satistacton,

and competence fram understanding, we seek to

Understand mare.

‘Acquiring a sense of our innate mental and visual

capacities can enable graphic designers and ilustra-

tors to express their message with accurate intent. For

example if one’s goal i to visually explain a process,

then understanding how humans comprehend and

learn helps the designer create a well-defined informa-

tion graphic. If one's purpose isto evoke a passionate

response, then an understanding of how emations are

tied to memory enables the designer to create a poster

that sizzles. If one's purpose is o visualize dat, then

Understanding the constraints of short-term memory

‘enables the designer to create a graph or chart that is

easily grasped,

This book explores how the human brain processes

visual information, It presents ways to leverage the

stengths of aur cognitive architecture and ta com:

pena fr its limitations. It propases principles for

Creating graphics that are comprehensibe,

It examines the unique ways we

can provide cognitive and emotional meaning through

visual language. Most important, this book is meant

ble, and informatv

inspire new and creative ways of designing to infor,

We depend on visual language for its efficient and

informative value. As the quantity of global informa

tion grows exponential, communicating with visual

allows us to comprehend large quantities of data. We

often find that technological and scientif

rand ¢ nly be represented

through imagery. Using an informative approach

information

isson ple, it can

to visual language allows the audience to perceive

concepts and relationships that they had not

previously realized

10 Visual Language for Designers

ur neurons Seem tobe plugged in to the digital

ream, having adjusted tothe continual barrage of vi

ial information. With multiple w cling tet,

personal digital assistant, new media, cial imager,

video on demand, advertising banners, and pop-ups,

the f

ne time it takes fora viewer to understand and

dows, 5

we have come to appreciat that visuals re

duce

respond fo information. The sheer quantity of visual

ges relayed through new technology has led

some to cal imagery “the new public language

Visual communication i iting fr a multlingul,

slobal culture Ws pos.

ble to bypass differences in symbol perception and

languae

Using basic design element

e to convey our message through imagery

Gyorgy Kepes, influential designer and art educato

envisioned this in 1944, when he wrote, “Visual com=

munication

limits of tongue, vocabulary, or grammar, an

perceived by the iliterate as well s by the iterate

universal and international t knows n

apprehend concepts that

tae aitfcut to explain. By

izing tive layers of

dloubies to express mo

tion, the artist provides 2

_limpse of how each iter

connected ayer ofthe body

‘4 Visual language enables

ls fo depict processes and

systems in their entirety 50

tne can understand the Dig

perspective. This aigron

ofa campus enterprise

system details each com

ponent ofthe system while

resenting the global view,

Taylor Mark, XPLANE,

United States

Visual Language for Designers

(Communication through imagery has other advantages

‘2s well To explain something hidden from vew, such

28 the mechanics of a machine or the human body,

2 cross section ofthe object ara transparent human

figure works well When we need to describe an invis-

ible process, such as how a mobile text message is

transmitted, iconic forms interconnected with arrows

can be used to representa system and its events. To

communicate a dificult o abstract concept, we may

‘choose to depict it witha visual metaphor to make

the idea concrete. Precise charts and tables help to

‘tucture information so audiences can easily absorb

the facts. When we wish to instigate a cal ta action,

we find that emotionally charged imagery is the most

memorable. We see that a graphic with humor ar nov

tly can capture our audience's attention and provide

‘motivation and interest, And when the tsk cals for

an immediate response, we know that a graphic will

provide quick comprehension. The power of visual

‘communication is immeasurable

> this snapshot of social

‘media trends onthe

Intemet was created for

Business Week magaziae

The clear and precise

Pinel graph provides the

coherency we need to make

comparisons, find patos,

‘and appreciate the richness

ofthe data,

‘Arno Ghelf, United States

Social Technographies Categories Percent of each generation in each Social Technographics category

ae> omen “ea” “Soe “Seo” “Sea “ae”

sabi

“ae asta

Introduction 13

‘The Designer's Challenge

The never-ending flood of facts and data in our con:

‘temporary word has caused a paradigm shift in how

\we relate to infarmation. Whereas at one time infor:

mation was community based, slow to retrieve, and

often the domain of experts, information 's now global,

instantaneous, and atten in the public domain. We

row want infarmation and content in our avn hands

{and on aur awn terms, We maintain an underying

belief thats aur fundamental right to have access

towellstructured and organized information. As a

result, information design is exploding as organizations

and individuals serambie to manage an overwtelming

‘quantity of content. Understanding the most effectve

‘ways to inform is now a principal concern. Accord

ing to professor of information design Dino Karabeg,

“informing can make the difference between the tech-

nologically advanced cuture which wanders aimlessiy

and often destructively, and a culture with vision and

direction."*

This has profound implications for graphic com

munication. There isan inereasing demand forthe

information-packed graphic, geater competion for

‘an audience's visual attention, and ever mote complex

‘sual problems requiring orignal solutions. There are

requirements to design for pluralistic cultures and a

Continuous need to design forthe latest technologies.

‘As part ofthis new path, visual communicators need

sense of how the mind functions. Effective informative

graphics focus on the audience. An increased aware:

ness of how people process visual information can

help the designer create meaningil messages that are

Understood on bath a cognitive and emotional eve,

[An informative image isnot only well designed; it cap-

‘ures bath the feeling of the content and facitates an

14 Visual Language for Designers

Understanding oft. The final product affects how the

audience perceives, organizes, interprets, and stores

the message. The new rale of a graphic designer isto

direc the cognitive and emotional processes of the au-

dience. In shaping the information space ofa visually

salurated world, efficient and accurate communication

is of primary importance.

Step Inside

Visual Language for Designers ts based on research

{om the interconnected fields of visual communica

tion and graphic design, learning theory and instruc

tional design, cognitive psychology and neuroscience,

‘and information visualization, The imagery incorpe-

fates an expansive definition of wsual design, exem-

pliying the diverse fields from which this research is

— —-

3(=)-leJ=

The human information pro

cessing system s the model

that cognitive scientists use

to understand how people

transform sensory data nto

‘mesningt information,

Visual Perception: Where

Bottom-Up Meets Top-Down

We are able to see a picture because reflected or

‘emitted light focuses on the retina, composed of more

‘than 100 milion light-absorbing receptors. The jab of

the retina isto conver this ight energy into electrical

impulses forthe brain to interpret. One could say that

the mechanics of sual perception center on the fo

vea, the region of the retina that gives us sharpness of

vision, The fovea allows us ta distinguish small objects,

‘etal, and cola. Because the fovea Is small, ust a

limited part of our visual weld is imaged on It at any

‘moment in time. Most visual infarmation falls an the

periaheral areas of the retina, whete the sharpness of

vision and detail fal off rapidly from the fovea,

ur eyes must repeatedly move to keep the object of

‘mast interest imaged on the fovea. These rapid eye

mavements, called saccades, allow us to select what

\we atlanta inthe visual world. The eye perfrns

several saccades each second. In between saccades

there are brief fuxations—around three per second —

hen the eyes are neatly at rest. This is when we

‘extract visual data from a picture and process it. The

visual system continuously combines image informa-

tion from one ization to the next

Unlike data streaming into a passive computer, we

perceive objects energetically, as active participants.

‘though our visual awareness is driven by the external

stimulus, known as bottom-up processing, our percep

tions are also driven by our memories, expectations,

and intentions, known as fop-down processing. Visual

perception isthe result of complex interactions be-

tween bottom-up and top-down processing,

RETINA

oven

(OPTIC NERVE

‘A The fovea isthe port af ¥ Visul perception results

the eye that gives us the trom the complex interac:

greatest acuty af vision, ‘tons ofbttom-up and

‘op-iown processes

Driven by an Driven by prot

external stimulus knowledge, goals

and expectations

Getting Grophics 23

ur visu ys

highly attuned to wsua!

‘maps the many visual

ofa primate bai,

process distinct visual

form, 20d color

Published in Science

‘magazine for an article by

David Van Essen,

Charles Anderson, and

Daniel Flleman

> inthis visualy ich

‘explanation of Hind

osmoigy 2 vewer wil

bottom-up processes. T

‘Annie Bisset,

Annie Bisset tusration,

24 Visual Language for Designers

Bottom-up visual processing occurs early in the vision

process without conscious attention or efor, propelled

by the brains persistent need to find meaningful pat

tems in the visual environment. When we happen to

gance ata

cture or a scene, we de!

ct motion, ede:

5 of shapes, color,

bottom-up proc

ntours, and contrasts through

s9es withou! conscious awareness

As our bran processes these primitive features, it

discriminates foreground trom background, groups

elements together, and organizes textures into basic

forms. This occurs rapily, helping us to recognize and

Identiy abjects. The output fem bottom-up process

ing ls quickly passe onto ather areas ofthe brain and

Influences where we pl

phase of perception, top-down processing, is strongly

influenced by what we know, what we expect, and

ce our attention. This second

the task at hand. We tend to disregard anything that

's not meaningful or useful a the moment. Top-down

processing so affects our

Events in aur information-processing system accur

rapidly and are measured in millseconds or one thou

sanath of a second. As we interact withthe world, we

ontinualy process sensory data in parallel. Different

regions ofthe brain that are attuned to specific visual

atributes ofa picture, such as clot or shape, ae ac

tivated simultaneously. Accordingly, visual perception

produces @ network of activated neurons i the brain,

rather than a single concentrated area of activated

neurons. Massive parallel processing makes the act

of perception fast and efficient. Perception and object

ton would be quite slow if data were passed

from neuron to neuron in a serial fashion

Getting Graphics

2s

>

—

—

‘Sensory

Memory

Long-term

Memory

Sensory

Data

exter

Stimulus

Sensory Memory: Fleeting Impressions

When we process sensory data, an impression or brief

recording ofthe orignal stimulus registers in sensory

memory. Sensory memory is thought to have at least

‘wo components: an ianie memary for visual informa.

tion and an echole memory for auditory information.

‘Although the impression fades after a few hundred

millseconds, iis buffered long enough for some

potion to persist for further processing In picture

perception, the prominent features ofthe picture

along with our conscious attention influence what

wil be retained

26 Visual Language for Designers

See

Working Memory: Mental Workspace

Because we are compelled to understand what we

e6, we need a mental workspace to analyze, ma

nipulate, and synthesize information. This occurs in

working memory, where conscious mental wok is per:

formed ta support cognition. In working memory, we

maintain and manipulate information that i the focus

of attention, piece together sensory infornation, and

integrate new information with prior knowiedge. Like

sensory memory, working memory processes informa-

tion through two systems; visual working memory pro-

‘cesses visual information and verbal working memory

processes verbal information.

[A profound aspect of working memory is how it helps

us make sense ofthe word. To understand some-

thing, we have to compare it with what we already

know. Thus, a8 new information streams into working

‘memory, we instantaneously Search through reiated

information in our permanent store of knowledge to

find a match, Hwe find a match, we recognize the

‘object or concept and identity it fit is unfamiliar,

‘we make inferences about i

Both sensory memory

and working memory are

taught to process informa

tion in separate channels

sua) and ver.

Getting Grophics 27

bo ee |

LEISURE AROUND THE WORLD

ro cette mre ny es te et ee ene ren

INTERNATIONAL LEISURE: A SAMPLING

For example, upon viewing this map, we separate

‘igure from ground and immediately try to wentiy

the shapes as objec. We rapidly search through our

knawiedge base (longterm memory) to find a match

for the shapes. This activates our associated know

‘of maps and geograpty. Ifthe external depiction

ofthe map matches our generalized internal represen

tation, we are able to recognize the landmass as “the

world" and to understand the symbols from reading

the legend. f we cannot identity the landmass or have

no knowiedge of map reading, we will not under:

stand the graphic. The comprehension of a parteular

graphic is dependent on a viewer’ prior knowledge

nd ability to retrieve that knowledge.

28 Visual Language for Designers

Two well-known constraints of working memory are its

limited capacity and short duration, Although the c

pacity of working memory isnot fixed, it appears that

‘on average, a person can manipulate around theee to

five chunks of information in awareness at ane tine.?

Thus, working memory is considered a bottleneck in

the information-processing system. One can easily

sense the limits of working memory by performing a

‘sequential mental operation, such as multiplying two

large numbers. At some point, more partial results are

needed to perfor the multiplication problem than

working memory can handle. That is when we typically

reach for paper and pencil or a calculator

This statistical map was

created for @ Newsweok

Education Program for

highschool students to

lear how to interpret and

Eliot Bergman, Japon

In adaiton tots limited capacity, the short duration

af working memory alsa affects our cognitive abies.

New information in working memory decays rapidly

Unless the information is manipulated or rehearsed

For example, we must mentally repeat dictions uni

we can write them down or they will quicky fade away.

Individual factrs also affect the constraints of working

‘memory. Age isa factor, working memory capabilties

increase with maturation but decline in old age. Work

ing memory is also affected by the speed with which

‘an individual processes information. Speediar process.

ing results in a greater capacity to handle information.

Distractbilty is another factor, People who are adept

at resisting distractions, which are known to overload

‘working memory, have a greater functional capacity

Final, a person's level of expertise affects working

‘memory. With a great deal of domain-specific know-

edge, an expert isnot as easly averwhelmed when

performing associated tasks as is a novice *

Conversely, the constraints of working memory can be

considered advantageous. The transitory nature of in

formation in working memory enables us to continually

change cognitive direction, providing the flexibility to.

shift the focus of our atention and processing to what

‘ever is most important inthe environment, In terms

af picture perception, this allows a viewer to instantly

perceive and consider a newly discovered area ofa

pieture that may be easier to comprehend ar of greater

Importance. The limited capacity of working memory

creates a highly focused and uncluttered workspace

that may be the perfect envionment for speedy and

efficient processing of information ?

‘As portrayed inthis graphic

for Elagance magazine,

Information in working

memory decays rapid

‘Ronald Blommestin,

The Netherlands

Getting Graphics

29

All About Stem Cells

‘Stem celts are the origin fal cas in the body (every cell stems" from this ype).

Under the right conditions, stem cells can become any ofthe body's 200 iflerent cel types.

pamrowe, sou

Seen eee mc a

rast “ape - - ma

ores cat at tarde

eed - Se ae fo

“Tiind 1008 seus atncese 10608

eat ne

= ee

= ed

oe =) 1

OMOr

f= SOsmnmvs

Onna Qusxsumun

Ormerod

Orme as sanone

on tne et nt pt nt ite a ee tn ind

raat

©.gauruemnn nemeatee CEES)

ommeresirunte [fucse

4

(© reads ea non mange bt ae EIEIO) O eno iat. es ead

enna ere eres SE

Saeaee una meenee meio a

‘er énom 5B Aten Q Stir teas 1) Cw 8.2 Moderne. henson 5.5 onic .25

30 Visual Language for Designers.

‘4 chatorging content

Inreases the cognitive load

on working memory. This

_raphic explaining stem

cel research incorporates

stvera effective techniques

Tor reducing the load, such

35 icone ilusrations,

sequencing, and arrows

‘gel Homes,

United States

> This stustration depicts

‘the memeries activated in

‘one man ashe obseres 3

pestoenic scene. Long

term memory stores numer

ous types of memories.

Joanne Haderer Miller,

aderor& Maller

Biomedical at,

United States

Cognitive Load: Demands

fon Working Memory

While many of the cognitive tasks we perform, such

as counting, make litle demand on working memory,

ather tasks are quite taxing. Demanding tasks include

such things as acquiring new information, solving

problems, dealing with novel situations, consciously

recalling prior knowledge, and inhibiting ielevant

Information.!® The resources we use to satisfy the

‘demands placed on working memory are known as

cognitive load,

When a high cognitive lnad impinges on working mem-

cry, we no longer have the capacity to adequatoly pro-

cess information. This overioad effect atten results in @

fallure to understand information, a misinterpretation

of information, or overlooking of important information,

Mary challenging tasks associated wth complex visual

Information make high demands on working memory.

Designers af visual communication can reduce cogn-

te load through various graphical techniques and

approaches that are discussed throughout this book.

Long-Term Memon

Permanent Storage

When we selectively pay attention to information in

working memory, iis likely to get transformed and

encoded into long-term memory. Long-term memory

is a dynamée structure that retains everthing we

know. It's capable of string an unlimited quantity of

Information, making it functionally ifrite. Knowledge

in long-term memory appears to be stored perma-

renity—though we may have difculy accessing it

Educational psychologist John Sweller describes its

significance: "Because we are not conscious f the

contents ofthe long-term memory except when they

are brought into working memory, the importance of

this store and the extent to which It dominates our

cognitive activity tends tobe hidden from us."!

Long-term memory isnot a unitary structure because

not al types of memories are the same. We remember

facts and concepts, such as basic color theory; we

remember chldhaed events, such as playing aur fst

instrument, and we remember how ta perform a task,

lke riding a bieyee. Accordingly, long-term memory

appears to have multiple structures to accommodate

different types of memaries. Semantic memory s a

sociated with meaning: it stores the facts and concepts

that compose our repository of general knowledge

About the world, This includes the information we

‘tract from pictures. Episodic memory is autobio-

raphical. I stores events and associated emations

that relate to experiences. Procedural memory isthe

storehouse of now to-do things. It holds the sks and

procedures that enable us to accomplish a task.

Getting Grophics 31

BEd int Design Process cuide

a

Encoding. Although some information is automaticaly

processed from working memory int long-term mem:

‘ary withaut conscious effon, encoding into long-term

‘memory generally invoives some form of conscious

rehearsal or meaningful association. Maintenance re-

hearsal is simply a matter of repeating new information

untl its etained;elaborative rehearsal occurs when

we analyze the meaning of new information and relate

itta previously stored knowledge in long-term memory.

Research suggests thatthe more ways we can connect

new information with old information, the more likely

its to be recalled, In addition, connecting information

‘om both the visual and verbal channels facilitates

encoding to long-term memary.

32 Visual Language for Designers

Depth of processing. Cognitive researchers think that

depth of processing significantly affects how Iikely

it is that information wil be eecalled from long-term

memory. When a viewer focuses aly on the physical

aspects of a word or graphic, the information isnot

stored as deeply as when the viewer focuses on the

semantic aspects, which are those that have mean

ing, For example, fa viewer concentrates only on the

shapes and colors ofa graph, the information wil not

be processed as deeply a ifthe person studied the

sg12ph, followed the flow of explanations, and under

‘stood its meaning. Encoding atthe semantic level

is superior to encoding atthe perceptual level. The

important point that cannot be overemphasized is

that we have @ superioe memory for anything that is

processed atthe level of meaning

Depth of proessig can be

understood by ooservng

this chart that depicts the

processes of print design.

Following the horizontal

path of each process for

2 coherent understanding

results in deeper encoding

than focusing only on the

layout, colors, and shapes

ofthe elements

Gordon Cleplak,

Schwartz Brand Gro,

United States

SCHEMAS: MENTAL REPRESENTATIONS.

‘To store a ifetime of knowiedge in long-term memory,

\we need it in an accessible form. Not surprisingly,

\we achieve this by classifying and storing information

in terms of what t means tous. “New information is

stored in memory—not by recording some literal copy

‘ofthat information but, rather, by interpreting that

Information in terms of what we alteady know. New

Items of information are itn’ to memory, soto speak,

in terms oftheir meaning,” write researchers Elizabeth

‘and Robert Bark."

Cognitive scientists theorize that the knowledge in

long.-term memory is organized in mental structures

‘called schemas. Schemas form an extensive and

elaborate network of representations that embody our

Understanding ofthe world. They are the context for

interpreting new information and the framework for in

‘grating new knowledge. We rapidly activate schemas

ta conduct mental processes, such as problem solving

‘and making inferences.

Unlike a perceptual experience that focuses on unique

features, a schema isan abstract or generalized rep-

resentation. There are schemas that represent abjects

‘and scenes and schemas that represent concepts and

the relationships between concepts. When we see a

house, we natice is architectural syle, the materials

from which itis bull, ts cols and textures, an the

surrounding environment. Although each houses

unique, each ime we encounter one ofthese struc-

tures we are able to identify it asa house, whether i

is @ hut constructed of mud and straw, a farmhouse,

‘ora townhouse. This is because we have a general-

laed schema of what constitutes a house. A general

schema for house might include a place where people

lve; a structure with rooms, windows, dears and root

‘and a place ta sleep eat, and bathe.

Our schemas are constantly changing, adapting, and

accommodating new information, contributing tothe

‘dynamic nature of long-term memory. Every time we

encounter new information and connect ito prior

knowledge, we are adapting a schema to assimilate

‘this new information. When schemas change or new

schemas are constructed through analogy, we cal this

occurrence fearning. And when a person becomes

very skiled in a parieular area, having constructed

thousands of complex schemas in a particular domain,

we consider the person an exper.

Retrieval. Our sole purpose in encoding information

into long-term memory i o retrieve the information

when we need it. Unfortunately, as we have al exper:

fenced, this is not always a straightforward process.

According tothe Bjorks, “The retrieval process is

erratic, highy fallible, and heavily cue dependent."!>

Information recall is accomplished by a retrieval cue,

which isthe plece of information that activates assoc!-

ated knowledge stored in long-term memory. Retrieval

{cues can be of any form—an image, a fact, an idea,

an ematon, a stimulus inthe envionment, or a ques-

tion we ask ourselves.

When long-term memory is cued to retrieve stored

‘memories, the cue activates associated schema,

Activation quickly spreads to other schemas inthe

network. A common experience occurs, for example,

‘when a person hears an old song and tries to remem-

ber the band that recorded it. The song isthe cue that

retrieves associated schemas from long-term memory.

Ifthe right schemas are retrieved, the person wil

remember the band's name. failure to remember

something is offen the result ofa poor retrieval cue

rather than a lack of stored knowledge.

Getting Graphics 33

‘Automaticity. Many schemas, such as word recogni

tion, become automatic through practice. Over time

‘and with repeated use, mare complex mental opera

tions also become automated with practice. When

this happens, the procedure i processed with less

Cconsciaus effort. Since warking memory isthe space

where conscious work is performed, automaticity

‘decreases the lead on working memary.*

‘A good example ofthis occurs as someone learns

to read. Upon one's frst encounter with the word

cat, thre letters or three perceptual units are hela

in working memary while the word is deciphered. AS

2 reader gains experience, the word catls chunked

inta one perceptual unt until eventually, recogniz-

ing the ward cat becomes an automatic process with

little imposition on working memory It's not uncom.

‘mon for people with expertise ina fet to perform a

‘ask without needing to pay deliberate attention to it

‘As the automaticity ofthe schema frees up cognitive

resources, the expert can use working memory to

‘competently deal with more complex tasks, such as

solving probloms or handiing novel situations. This ean

be observed in experienced athletes, master teachers,

and expert designers.®

Mental models. Whereas schemas form the underb

ing structure of memory, mental models are broader

Conceptualzations of how the word works. Mental

models explain cause and effect and how changes

in one objector phenomenon can cause changes in

another. For example, users of graphic software have

‘2 mental model of how layers operate. The mental

‘model contains knowledge of how a layer is alected

34 Visual Language for Designers

by maving it above or below anather layer and the ef

{ect of increasing or decreasing ts opacity. This mental

model i easly transferred to any graphic sofware that

uses the same paradigm. Thus, mental models help

us knaw what sults to expect

‘ith an understanding of schemas and mental mad-

cls, graphic designers can begin to consider how an

audience might understand a visual form of communi

catian. When someone looks ata graphic, the objects,

shapes, and the overall scene activate associated

schemas and mental made's that enable the viewer

ta make inferences about the visual and construct an

interpretation of it.

4 created forthe WRC

Handelebod, this eraphic

suggests the automaticity of

‘many of our actions

‘Rhonaid Bionmestin,

The Netherlands

> this graphic portrays a

novel way of seeing the

Interlationshios arent

In cognitive processes,

“Lane Hall, United States

Getting Graphics 38

DUAL CODING: THE VISUAL

AND THE VERBAL

Yerba and visual information appear to be processed

through separate channels, refered to as dual coding.

(One channel processes visual information that retains

the perceptual features of an abject or picture and

fone channel processes verbal information and stores

the information as words. Although the systems are

independent, they communicate and interact, uch as

wien bath image and concept knowledge are retrieved

from long-term memory. For example, upon hearing

the name Salvador Dalla person might retrieve both

image-based and verbal information from long-term

‘memory. One might construct mental images ofthe

artist's paintings and also recall biographical informa.

tion about his ite.

‘This dual system of processing and storage explains

‘why memorized information is mare likely 0 be =

‘Weved when its stored in both visual and verbal form,

That ls why associating graphics with tex or using an

‘audio track with an animation can improve information

recall Placing pictures together with words also allows,

these two medes of information to form connections,

creating a larger network of schemas.

36 Visual Language for Designers

‘THE AUDIENCE'S COGNITIVE

CHARACTERISTICS

It may not be possibie to fully predict how an audience

will peceive and interpret a picture because of the

Complex nature of human experience and the variable

Cognitive skils among individuals. Yt an awareness

(ofan audience's cognitive characteristics can bring

designers closer to this goal. In her book Research Jato

‘Mustration, professor Evelyn Goldsmith categorizes the

cognitive resources and abilities that could affect an

individua' abilty to comprehend a picture.

‘The first characteristic is developmental evel. The

implicaton is that development, rather than age, is 2

more accurate predictor ofa person's cognitive abii-

ties. less sklled viewer may interpreta picture Iter-

ally although the intended meaning is metaphorical.

‘The ability to interpret more complex types of visual

‘expression comes with mature development. Also,

visual skis vary with developmental level. Visual skis

such as depth perception, color differentiation, and

acuity vary at diferent stages of development

Distractibilty isthe ability to focus an what is impor-

tant while inhibiting distraction from other events and

information. In terms of graphic comprehension, an in-

dividual capable of inhibiting distractions wil be better

‘able fo concentrate on relevant information ina visual

Not surprisingly, younger viewers find it mare dificult

to clse their minds to extraneous information,

> The cognitive characteris

ties of developmental evel

‘and aistracibity come

into play when designing

fora young audience. These

display graphies use bright

colors and humorous i

lustations for an aquarium

exhib

Greg Ditzenbach,

‘McCullough Creative,

United States

te

6

eelainy: (3

This information graphic vi

sualies the potential global

tage of wind energy de

Dicted in maps and grap,

‘Advanced developmental

‘and visual literacy levels

fre required t comprehend

amples sraphies

‘Kristin Cute, University of

Washington, Unite States

‘Another characteristic atthe top of the lst is visual

iteracy. Athough it may not tke training to recognize

the objects in an image, a comprehensive understand:

ing of picture involves the ably to fully decode

the vigual message. Knowledge ofthe symbols and

graphical devices used in one's culture as well as an

Understanding ofthe context are required. Learning to

accurately read a picture isa result of education and

‘experience. For example, i takes an advanced level of

visual literacy to analyze and interpret an information

graphic using many types of graphs.

38 Visual Language for Designers

Politics & Potential

The audience's level of expertise should significantly

affect design decisions. Experience with the content of

2 picture isan important predictor of a ewer’ bility

ta comprehend a graphic. Experts are knawn to orga

nize complex patterns in the visual environment into

{ower perceptual units, which reduces cognitive oad.

Thus, viewers with domain-specific experience are less

likely to get overioaded when perceiving a complex

visual as compared to novices.

‘Motivation isan important factor in whether an aud

fence member wil have an intrest ina picture. A view-

{ers motivation is typically based an his or her goals

for viewing the graphic. Is the graphic being viewed

for aesthetic appreciation ori it required for perform-

ing task, such as fixing a bicycle? Does the graphic

‘explain a complex concept that must be learned? Or

is ta bland marketing mailer for which the viewer has

no use? With enough motivation, a viewer will attend to

‘and work at understanding a graphic.

i

it

i

i

|

Catureis another signiiant facto in graphic creation,

Many cognitive skis are culturally based—ways and

pattems of thinking, symbol and color interpretation

‘and visual associations with verbal language, to name

2 few. Culture provides the context or ens through

‘which people interpreta picture, and therefore culture

affects cognitive processing. As the global exchange of

people and ideas continues to increase, accommoadat-

ing the cognitive conventions ofa pluralste culture is

2 fundamental requirement of effective design

Reading skis often correspond tothe users under

standing ofa graphic. People with low reading levels

‘may nat be proficient at following a visual hierarchy or

finding the most relevant information. They may net

be experienced a allocating their visual attention to

‘a picture in the most efficient manner and may miss

Important information. * Reading level also atects how

‘wel the viewer wil read tiles, captions, and call-auts

‘and how he or she will integrate text and images.

‘An imgertant cognitive

‘hil to consider n complex

_raphies isthe reading

level of the audlence. In

{this information eraphic

{or the Sydney Morning

Herald, call-uts are exten

‘ively sed f explain the

ramped conditions atthe

Opera Theatre

(Ninian Carter Canad

Getting Grophics 39

INFORMATIVE VALUE

[Another aspect of cognition relates to a graphic’s

informative purpose. In his book Steps to an Ecology

ofthe Mind, Gregory Bateson writes that information

's a difference that makes a difference." This stato

ments profoundly true for visual communication. The

‘sual language ofa graphic and every compositional

element it contains potentially convey a message 10

the viewer.

By determining a graphie’s informative purpose, de-

signers can strategically organize a graphic to invoke

the most suitable mental processes. For instance,

‘some graphics only request recognition from the

viewer. They require the viewer to notice, to become

aware—of an organization, an event, a product, or an

‘announcement. These graphics must be magnetic to

attrac the viewer's attention and sustain it for as long

as possible. The viewer's gaze must be directed to the

‘mast important information. And the graphic should

bbe memarabe, so that the viewer encodes the mes

sage into long-term memory

(ther graphics are crested to extend the viewer's

knawiedge and reasoning abilities. The value of maps,

diagrams, graphs, and information visualizations fs to

make things abundantly clear and move the viewer

beyond what he or she could previously understand,

Upon viewing one ofthese visuals, the viewer should

be able to see new relationships. Here, the graphics

must be clean and wel organized and must accom-

‘modate ease of interpretation and reasoning. Then

there are graphics designed to assist wth a task ora

procedure, such as assembling furniture. In order for

the graphic ta be effective when the viewer becomes

‘2 user, must be accurate and unambiguous, leaving

ro room fo misinterpretatio,

By understanding the mental processes required to

meet specific informative goals, designers can find the

most suitable graphic approach for their purpose. The

principles discussed in the next section ofthe book

describe ways to achieve this.

> The rch, stoking textures

‘Aatian Labos, 3 Studios,

Romania

tion of how dita! camera

‘and organized to

Kevin Hand, United States

40 Visual Language for Designers

Getting Graphics 41

SECTION TWO

1: Organize for Perception

irect the Eyes

teduce Realism

lake the Abstract Concrete

5: Clarify Complexity

6: Charge It Up

“For design is about the making of things: things

that are memorable and have presence in the

world of mind. It makes demand upon our ability

both to consolidate information as knowledge and

to deploy it imaginatively to create purpose in the

pursuit of fresh information.”

“Jean Manvel Davivier,

Jean-Manuel Duvivier

IMustration, Bel

Bors Lube, Studio

Intemational, Croat

44 Visual Language for Designers

PRINCIPLE 1

“Vision is not a mechanical recording of elements, but

rather the apprehension of significant structural patterns.”

RUDOLF ARNHEIM

Cur visual system is remarkably agile. Ithelps us per-

form tasks necessary for survival in our environment.

Yetwe are able to apply these same processes to

perceiving and understanding pictues. For example,

without canscious effort we sean aur surtoundings to

‘extract infarmation abaut what is “out there," nating

ifthere is anything of importance in the envionment.

Similarly, without conscious elfor we scan a picture

ta acquire information, noting if there is anything of

Importance in the visual display Allof this occurs

effortlessly, before we have consciously focused our

attention

The processes associated with early vison, called

preattenve processing, nave generated a great deal

‘of research that can be applied to graphic commu

nication and design. By understanding how viewers

inaly analyze an image, designers can structure and

‘organize a graphic soit complements human percep-

tion, The goal sto shit information acquiston tothe

perceptual system to speed up visual information pro-

‘cessing. This is equivalent to giving a eunner a head

start before the race begins.

Early vision rapidly scans a wie visual eld to detect

features in the envionment. This frst phase of vision

is driven by the atibutes of an object (the visual

stimulus), rather than a conscious selection of where

talook. Upon detecting the presence of wsual fea

tures, we extract raw perceptual data to get an overall,

impression. This daa is most likely “mapped ito di

ferent areas in the brain, each of whichis specialized

to-analyze a diferent property.” From this rapid wsual

analysis, we create some frm of rough mental sketch

or representation?

Later, vision makes use ofthis representation to know

where to facus our attention. tis under the influence

of our preexisting knowledge, expectations, and goals.

For example, using the low-level visual system of early

vision, we might register the shapes and color features

we see in a graphic. Later, vision directs our attention

to those same features and uses knowledge stored

in long-term memory t recognize and identify the

shapes as people. These two stages af vision form 2

complex and lttle understood interaction that provides:

us witha unique visual intligence.

Organize for Perception

[ORGANIZE FOR PERCEPTION

4s

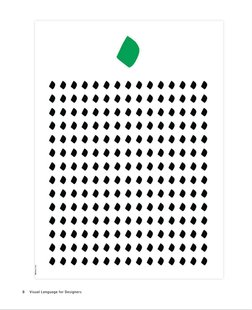

ereeenanenett

ereeeneeetett

ereeenanetett

Hreeinanenete

wi ett

wit it

i it

46 Visual Language for Designers

Hreeenanenett

ererenaeetett

ererenenetett

Srerenerenene

Seeernetehiet

Hhetedoteadtt

iehettetecttc

In these iustrations at an

Underwater landstide for

Siete American, vivid

textures enable ust de

Lingus between land and

58a. The dynamic texture of

the ocean projects a sense

ofthe oncoming tsuram

Dovid Fierstein,

Dovid Firstion Mutation,

‘Animation, & Design,

United States

Perceptual Organization

The significance of early vision is that it organizes our

perceptions and gives structure and coherence to sen-

sory data. Without perceptual organization a picture

might appear tobe a chaotic st of disconnected dots

‘and lines. During our preconscious visual analysis,

\we perform two primary types af perceptual organiza-

tion—dlscriminating primitive features and grouping

visual information into meaningful units

Primitive features are the unique properties that

allow a visual element to pop out ofan image dur

Inga search, because they are the mast salent or

prominent. Examples of primitive features are colo,

‘motion, orientation, and size. We later merge these

features into meaningful objects through the guddance

af our focused attention. Primitive features also allow

Us to discriminate between textures, which we see as

regions of similar features on a surface. When we see

the dscontinuatin of feature, we perceive it as a

border or the edge ofa surface. This process, known

as texture segregation, hes us identify objects and

forms and isa related preattentve process.

Whereas the detection and discrimination af prim

tive features tol us about the properties ofan image,

the preattentve process of grouping tells us which

individual parts go together. Before consciously paying

attention, we organize sensory information into groups

tr perceptual units. This provides information about

the relationship of elements to each other and tothe

whole. A basic perceptual unit can be thought of as

any group of marks among which aur attention is not

divided. A simple example ofthis concept occurs

when we perceive a square. We tend to see the whole

shape ofthe square rather than four straight lines

intersecting at ight angles. Application of the group-

ing concept can help a designer ensure tha viewers

perceive visual information in meaningful units

Using visual language that speaks toa viewer's preat

tentive visual processes—discriminaton of primitive

features and grouping parts into wholes—enables a

designer to quickly communicate, grab attention, and

provide meaning. This principle can be applied to

informational and instructional graphics, promotional

materials, warning signs and wayfinding, information

visualizations, and technical interfaces,

Organize for Perception 47

Da ane es Res

Reece eterna pa arty

BUT HAS LESS THAN 2 PERCENT OF THE

Proofs

Boosting Cognition

‘ acy tr : to preex a

s sensor ¢ s ample, emphasizing inacone PS __

Fi ¢ : : : Schwartz Brand Grow

proce at the seu " the Acce important area

' cous atten ; en udience a :

pv 3h data should

ens x . t

: nudience per f 1 ultimately enhancing comprohe

w ‘Compre , sequitio bud

tent that th reat cd me .

. : process an

: aa ca portunities for miscomp

Organize for Perception 49

fo

(OF U.S, URBAN TRAYEL

1S 2 MILES OR LESS.

RIDE YOUR BIKE

TOFIGHT °

WARMING.

Wired magazine,

wal bars wth

y

and similar color tor nto

their own perceptual soup

The individual groups

form into one whole graph

because of proximity and

breensting ko

howto

‘Arno Ghelf Tatler staro,

Unites States

50 Visual Language for Designers

‘Mark Boedian,

(cut Bar & Company,

United States

market penetration

50 years

Applying the Principle

‘Accommodating our prattentve visual processes

through design requites thinking in terms of how the

visual information wil be detected, organized, and

‘rouped. Fortunately, its nat dificult to predispose

the viewer to a wel-organized visual structure. The

low-level visual system is continuously Seeking a stim.

ulus inthe environment to provide focus and draw the

‘eyes. When a design cals for quick recognition and

response, graphics that emphasize one pronounced

primitive feature, such as line orientation or shape,

can be placed against a background with few distrac

tors, This prietive feature willbe detected during a

preattentve rapid sean

When a project requires an emphasis on aesthetic ex-

pression, the designer can take advantage of how early

vision segregates features into textures. Using texture

as a prominent feature can add visual depth and

complexity to a graphic. And because we are adept at

detecting texture differences, thi can offload some of

the processing normally placed on working memory to

the perceptual system

The low-level visual system also seeks to configure

parts ofa graphic into a whole unit when they are

Clase together or have similar features. One example

is how we perceive elements that have a common

boundary as one unit, From a compositional perspec

tive, grouping provides opportunities for emphasis,

balance, and unity ina design.

By organizing the structure ofa design through

‘emphasis of primitive features or through grouping

individual elements, viewers wil quickly detect the

‘organization of the graphic. Many designers intuitively

Use these organizing principles, but an awareness

of the audience's preattentve capabilties isa way to

intentionally improve the communication quality of any

informative message,

The way we preston:

tively organize texture

Into shapes canbe clear)

‘apoptosis (ce! death.

‘Drew Bery, Walter and

Elin Hall Institute of

Medical Research, Australia.

Drganize for Perception $1

than halfa century and

of research leaders dedicated to

Soenrem ranean 1

52 Visual Language for Designers

‘of Nw York City bulsings

for Sloombere Markets,

magazine.

oan Christe,

Bryan Christie Design,

United States

> in this college comous

‘map, outlined green areas

accentuate regions within

‘the campus. This helps us

‘roup the buildings thin

‘each region, faci

tse ofthe

‘David Horton and

‘Amy Lebow,

Phitearaphia,

United States

“ ' t | ‘

—i. Ma i 4 d

ee ee meal = =

ont: ents

et} at a © ey

oe oe neo)

Po iss Sj I <0:

feels GL S925 GU Sygsy ILS KAS 2T. oiflg,d cist

MS B28 (99> Tub pal sign oo Pg SSS I. old

HS P99 95)578 ST Ki ob dee gb SIO 39.55

PP OU: CS) SN cats!

BSE 39 Eyed Col AU Se8 yoy sodbeg saysleh od

bab al Spot Gia gs a Ct eee

See oe ene aes ee

ae Sete

b bP 9590 ToL Se, Ba Boe hed

pola a

Sovn Bechira,

2X3 studios, Romanis

Rosen beaeeieaae Gui

fae! re PNY rh: PNPER CLS

iS

gd Salam os A> IAS 3! p95 Wc ELS & Cougs 3S

ei ee aris Sep aerate goles Glass ole

EO SHIR Mba le Sail alge Ol sWejgs

PP Na Re I eg He Shy

Lore: SRSA Se eae: OSs OES phe

Pl cho ja Jal Rim . esol) 6 pilo iol Gs a 3 Col

PO eG we im Peete ee es mes)

56 Visual Language for Designers

e cus cy 2

rE T

Bansh: OENO

TEXTURE SEGREGATION

tothe inux of sensory

data isto organize primitive features into segmented

regions of texture. In pictures, texture can be thought

of asthe optical grain ofa surface. We unconsciously

unify objects into regions that are bound by an abrupt

change in texture. We perceive this change as defining

where one object, or form, ends and where another

One of ou ist respon:

begins. Once we segregate a region info textures, we

then organize it into shapes or objects that we identity

with conscious attention. Our knowiedge of texture

patterns helps us to identi objects.

Through texture segregation, we also separate

foreground from background. When we perceive a

ference between two textures, the textured area is

typically seen as the figure or dominant shape and the

area without texture is typically seen as the ground

‘oF neutral form. The relationship between figure and

‘round i a prerequisite for perceiving shapes and

eventually identifying objects. Color and size, also

contribute tothe fgure—ground perception.

Just as primitive features can induce the pop-out

effect, so can regions of texture. For instance, wien

2 surface texture is composed of uncomplicated primi

tive features, such as line orentation or shapes, is

58 Visual Language for Designers

‘easy ta cistinguish the texture frm its surroundings.

‘When a form with a complex texture is placed on a

busy background, the texture is harder to dis

and loses its pop-out effect.*

iminate

Texture perception also presents spatial information

depth perception.” The texture

«gradient on a surface contributes to our perception of

ject appears. When the texture’s

pattern on a surface is perceived as denser and fines,

by providing cues

hhow neat ofr ano

an object appears to recede in the distance; when the

pattern is perceived as less dense and coarser, the

object appears closer.

Our abilty to segregate textures during eary vision is

key to understanding the meaning of a graphic. An

analysis of texture shows that itis constructed from

Contrast, orientation, and element repetition. Designers

‘can manipulate these individual properties to convey

meaning, Texture can be expressive, capturing the es

sence ofan abject or mood. Texture can also simulate

surface qualities to help us identify and recognize ob-

jects. When given appropriate emphasis, texture can

become more prominent than shape and line.

‘A In these three dimen

sional displays to promote

organic textures to express

the natural beauty of

Croatia, Textures ae easy

peresved inthe early vision

example 80 competing

‘Boris Lubicle, Studio

Intemational, Croatia

> one can almost fe! the

‘gooey, meting textures

this poster. The powertu!

‘ype pops cut even against

the high-energy cols and

shapes because ofthe con

teats in coor and texture,

“arian Labs,

23 Studios, Roman

(hvstopher Short,

60 Visual Language for Designers

Tan Lynam, Tan Lynam

Creative Direction & Design,

Organize for Perception 61

Pec Tene

ei

EESeeV

Pherae)

with Text

Text

62 Visual Language for Designers

¥

agro

—

é av Oho

gto etter wien reat

rea a aan, tet,

Fat ty,

slater

obra Za,

Us EE, Nang

1 inimno zasjna ob

es lthice 2,

Sina 0300 Konce 3

feat Ning somovan je prs Bodin nk ki

pats roHlogodisyn ade NES Fits, Osobitg

2 cms ay nin ad se Zag ie

oa os aa el pe 38d tap ent ak

: Be

if Yoysuseen rn

VU Kolikog nays asia sit ae ideronon i Posetno

sc eh ag 2 ti Run hg Eno

esa ak, ai ih oni Uskani U Za poy RIO dob Klum | 028m pti

sae i i tel aa ps je ot ony eh

Seek i hans Pods cle iodo objay seine ogee Smo Ht

FHRATSRE CNC tll ejecta GoD KA

ime, ia hAa pfs NaC NTA KNIIGE kno means Nip dan da PRVE

arena seat Robi

Spe SR tes pera oani ts

, So gn giska

Organize for Perception 63

em Sieg ou i — YAMA

URTERT WIENER == UMLAUT DOPPELDEEKER

BRATWURST UASPRAGHE HAMSTER SCHMUSING =

sea SEE STRATE,

WAFFEEKLATSCN,-KLAT

{WEISSWURST: i

“VOLKSWAGEN POLTERGEIST-., WANDERLUST_

ESTER TIAN 7 PE ikistay=:

‘emer

OPILITO sr” =

MALE

WME LETMOT a

: ‘Si UNDERGARTEN a

: is — ae ;

a YAL Then

Ban in

Ausgewanderte Worter ini

WANDERWORT. ~~ “= = =

ALLEs BLAU? =

vacua

ugar Moe AEP KUIH

rs sl MAKAT aA

aad

near

PRT RAUEED,

UNDHEL

GROUPING

Understanding where abjects are located and how

they are arranged in space is essential for moving

‘through the environment. Perhaps that's why spatial

‘otganizatonis 3 fundamental operation of preatentive

perception, The low-level vsual system has a tendency

tw organze elements into coherent groups depending

(on how they are arranged and where they are located.

This preattentive configuration of pars into wholes

lets us knaw that a set of elements in a picture fs

associated and should be viewed as ane unit. During

later cognitive processing, the relationship among the

perceptual units and thet relationship tothe whale

becomes valuable information that conveys meaning

in a graphic

‘The perceptual organization of parts into wholes is

based on theories promoted by the Gestalt psychalo

gists inthe early twentieth century. Their principles

demonstrated that under the right conditions, combin-

ing parts into wholes takes precedence overseeing

the parts themselves. A few of the Gestalt principles

‘that determine whether a whole unt or ts parts have

visual precedence include proximity, sitar, and

symmetry. Elements that exhibit proximity are close

to each ather in space or time, We perceive elements

with proximity a belonging to the same group. We

also perceive elements that have similar visual charac

teristics, such as shape and texture, as one unit. The

symmetry principle states that we configure elements

inta'a whole when they form a symmetrical figure

rather than an asymmetrical one

66 Visual Language for Designers

In the past few decades, research in the area of

preattentive perception has added to our body of

knawiedge about the grouping phenomenon. These

findings have extended the factors that are thought

toiinfluence our natural tendency 1 group parts into

wholes. These newer principles include the concepts.

cof boundary and uniform connectedness. The bound-

ary principle states that fa set of elements is enclosed

with a boundary, such as a circle, we group those

elements together® Thus, when a boundary encloses

2 set af items, we perceive this as a unit eventhough

‘we would perceive the items as separate withaut the

boundary. Connectedness describes our tendency to

perceive elements as ane unit when they are ahysi-

cally connected by a line or common edge® This is

generally how we perceive diagrams.

‘A design that arranges elements into meaningful units

wil influence how weil the audience oxganizes, iter.

pts, and comprehends a visual message. Grouping

elements enhances the meaning of a graphic, because

viewers know that clustered elements are asso

ated. Visual search is speedier as a result of grouping

because iis faster to find information thats placed

in one location. Grouping elements together can also

make new features emerge. For instance, a set of ines

radiating from a center point might emerge as a Sun

form. Designers can take advantage ofthe conditions

that evoke grouping—proximity,simlaty, symmetry,

bounding, and connectedness—to facilitate visual

‘communication

‘United States

Organize for Perception 67

WE KNOW THE

PROPER SALARY

FOR EVERYONE

IN YOUR

DEPARTMENT.

68 Visual Language for Designers

Organize for Perception 69

rr

Ee)

70 Visual Language for Designers

THURSDAY

974380130

=

Gs

Ee

a

sf

si

a8

ge

ea

&

8

This poster fora graphic

design lecture tects the

lye tthe important ifr.

‘mation afonga spiraled

Tan Lynam, lan Lynam

Creative Ditection& Design,

Jaen

PRINCIPLE 2

[DIRECT THE EYES

“If the viewer's eyes are permitted to wander at will

through a work, then the artist has lost control.”

|IRCK FREDERICK MEYERS, The Language of Vial 4

Athaugh we think ofthe brain asa system that can

process massive amounts of data in paral, the

‘Quantity of input coursing through the optic nerve

‘every second is actualy more than the brain can

squeeze into conscious awareness. Thus, we shift

‘ur visual attention from ane locaton te another in

‘a serial manner to extract the information we wart.

‘An interesting feature inthe envionment may tact

‘our eyes, or an internal goal may diect our attention

Likewise, when viewing a graphic we attend to what

is most compeling. Prominent features ina graphic

‘compete for aur attention, so if we are not given visual

direction we may dwell on the wrong information or

become overwhelmed with toe much infarmation. To

find meaning in what we see, we must selectively at-

tend to what is important. A designer or iustrator ean

assist this process by purposeluly guiding the viewer's

‘eyes through the structure ofa graphic, Ths is one of

the more essential techniques visual communicators

‘can emplay to ensuee that viewers compcehend their

Intended message

Directing the eyes serves two principal purposes—to

steer the viewer's attenton along a path according to

the intended ranking arder and to draw the wewer's

attention to spectc elements of importance. When our

‘eyes scan a picture, we do not glance randomly here

‘and there. Rather, aur eyes fate on the areas that are

‘mast interesting and informative. We tend to fate on

‘objects, skipping over the monotonous, empty, and

Uninformative areas. This not surprising, since we

‘are continually seeking meaning in what we see. But

itdoes mean that each individual may scan the same

picture in his or her unique way depending on what

the person considers informative

Nevertheless, there are common tendencies and

biases in how we move our eyes around a picture. The

intial scanning process often starts in the upper let

comer asthe point of entry. We are biased toward let-

te-right eye movements and top-to-bottom movements

Diagonal movements of the eye are less frequent.

‘Mtr the fist several fixations, we mast likely get the

“gist” ofa picture, and then our eye movernents are

influenced by the picture's content, is horizontal or

vertical orientation, and our own internal infuences.

Itis debatable whether the dectional orientation of

one's wing and reading system contributes to eye

‘mavement preferences.

‘The eye movements ofthe viewer are erica to

‘graphic comprehension. Unlike other forms of com-

‘munication, such as reading, listening to music, of

‘watching a movi, the time spent looking at a graphic

can be remarkably brief, Purposefuly ditecting the

eyes makes it likely that a viewer will pick up the most

relevant information within a limited time frame. The

designer can guide the viewer's eyes by using tech:

riques implicit to the composition, such as altering

‘the postion of an element or enhancing the sense of

‘mavement, The designer can aso guide the viewer to

specific information by signaling the location with vi-

sual cues lke arrows, color, and captions. Visual cues

4 not cary the pximary message; their function isto

trent, point ou, or highlight crucial information,

n

72 Visual Language for Designers

AWATDUIE DU LDWOTEE

Both compostional and signaling techniques are

effective at guiding the eyes because they make use

‘of prominent features that are picked up early in the

perceptual process. Even though eye movements are

‘also controled by the viewer's expectations and search

‘goals, research shows that using compositional and

signaling techniques ta dlect the eye can be quite ef-

fective. In one experiment that gauged eye movernent

based on compositional techniques, an experienced

artist explained to the study authors precisely where

he intended observers of his at to look, Observers

‘were then allowed to view the at fr thity seconds

while their eye movernents were recorded. The scan-

ning paths of the subjects proved to be in “consider-

able concardance® with what the artist intended.

Signaling the viewer with arrows and color is known

to be effective when used in explanatory and informa-

tional graphics. Studies show that when an area ofa

sraphic is highlighted a its being discussed, such

asin a mutimedia environment, viewers retain more

information and are better able to transfer ths infor

‘mation than thase who didnot view the highlighted v-

suals? Other research has demonstrated thatthe use

of arrows as pointing devices reduces the time it takes

to search for speci information in a visual field?

In this visual study of early

transatlantic ners created

fora student projet, the

painting finger is a visual

ue syed fo ft the early

rao tansatantc liners

‘Chronopoulou kate,

{a Cambre School of

sual At, Begum

Direct the Eyes 73

Importance of Attention

‘The cognitive mechanism that underlies eye mave-

‘ment control is selective attention. When we extact

sensory data from a pictur, its momentarily regis

tered in our sensory memory in fleeting images. We

‘must detect and then attend to these images though

the process of selective attention to transfer visual

information into working memory. Through selective

attention, we send visual information onward through

the visual information-processing system

Cognitive researchers study eye movernents because

fee movements reflect mental processes. We typically

‘move our eyes, and sometimes our head and body, to

view an object withthe fovea—the part ofthe eye with

the sharpest vision. When doing this, our focus of at-

tention usually coincides with what we are seeing. But

the relationship between eye movement and atention

is not absolute, We can move our attention without

moving aur eyes, as when we notice something in

74 Visual Language for Designers

peripheral vision while looking straight ahead at some.

(one speaking. In this circumstance, the movement of

allention precedes the mavement ofthe eyes“ Because

altention and the eyes can be associated, intentionally

directing the eye helps to ensure they are aligned.

‘As discussed in Principle 1 (Organize for Percep-

tion), attention can be captured preattentively through

the bottom-up processing driven by a stimulus, ort

can be captured during conscious attention through

top-down processing. Designers can take advantage

of ether type of processing to direct the viewer's atten

tion. Incorporating contrast ar movement into a design

vl tigger attention through bottom-up processes.

Indicating the steps of a sequence through numbers

and captions will activate attention through top-down

processes.

This information graphic

created for itaché mage

zine explains how gasoline

engines werk, using as.

‘quence of numbers to guide

the viewer’ attention,

‘ge! Holmes,

Ute States

Enhancing Cognitive Processes

Promotes speedy perception. Vihen an observer's

visual attention shifts ta a predetermined location

ar along a preconceived path, it enhances haw the

person understands a graphic in many ways. Drecting

tha eyes promotes the afciency and speed of wsual

perception, enhances visual information processing,

and improves compretension. Specialy, when a

viewer scans a complex graphic, it takes time to get

ariented, to determine what is most important, and

to extract essential information. Viewers are known

to overlook important details in complex ilustrations

unless they are shown where fo attend. When a viewer

Is directed toa precise lation, however, search time

is reduced and efficiency i increased

Improves processing. During preattentve processing

attention 's unconsciously directed to features that are

‘most salient. Studies have demonstrated that view-

ers can be distracted by powerful but irelevant visual

information that captures thelr atentian even against

their intentions * Directing the eyes can help ensure

that irelevant information Is nether dulled upon noe

| Ome

eee | Saket

iat

processed. Moreover, when a viewer Is quicky guided

to the essential information, it diminishes the demands

placed on working memory that would have been ap

plied to finding important information. More resaurces

are then avalable for organizing and processing infor

mation 38 wel as assimilating new information €

This results in better understanding and retention.

Increases comprehension, Otecting the eyes can also

assist inthe comprehension af a picture. The types

of visual cues used in informational and instructional

raphics, such as acows and highlights, are more

likely to be understood than instructions were pe

sented in a writen form. Comprehension is also aided

by visual cues that provide structure, such as adding

numeric captions to emphasize the oder of a process

Organization is known to improve comprehension

because it provides a cognitive framework. Wellorga-

rized information helps viewers construct coherent

representations in working memory, making it easier to

assimilate new information into existing schemas.

This circular format por

trayng the ie cele of @

parasite directs the eyes

wit 2 continuous aro

{nd a number sequence,

Drovging a structure that

faclitates comprehension

Nigel Holmes,

United States

Direct the Eyes 75

Applying The Principle