Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Case Name: Sanlakas v. Executive Secretary, G.R. No. 159085

Case Name: Sanlakas v. Executive Secretary, G.R. No. 159085

Uploaded by

Jhoy Callueng ReyOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Case Name: Sanlakas v. Executive Secretary, G.R. No. 159085

Case Name: Sanlakas v. Executive Secretary, G.R. No. 159085

Uploaded by

Jhoy Callueng ReyCopyright:

Available Formats

Case Digest | Law Journal 2014

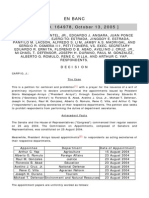

Case Name: Sanlakas v. Executive Secretary, G.R. No. 159085,

February 3, 2004

Justice

C.J. Davide, Jr.

J. Carpio

J. Corona

J. Carpio-Morales

J. Puno

J. Vitug

J. Panganiban

J. Quisumbing

J. Ynares-Santiago

J. Sandoval-Gutierrez

J. Austria-Martinez

J. Callejo

J. Azcuna

Stand

In the result

Concur

Concur

Concur

In the result

Separate opinion

Separate opinion

Concurs with J. Panganiban

Separate opinion

Dissent

Concur in the result

Concurs with J. Panganiban

On official leave

What is the subject of the controversy?

Proclamation No. 427 and General Order No. 4

What is the theme of this case?

Legal standing (Locus standi)

Mootness

Executive Powers

Facts:

- F1: On July 27, 2003, some three hundred junior officers and

enlisted men of the Armed Forces of the Philippines stormed

into the Oakwood Premiere apartments in Makati City

demanding, among others, the resignation of the President,

the Secretary of Defense and the Chief of the Philippine

National Police.

Case Digest | Law Journal 2014

- F2: In the wake of the Oakwood occupation, the President

issued Proclamation No. 427 and General Order No. 4, both

declaring a state of rebellion and calling out the Armed

Forces to suppress the rebellion.

- F3: By the evening of July 27, 2003, the Oakwood occupation

had ended. After hours-long negotiation, the soldiers agreed

to return to barracks. The President, however, did not

immediately lift the declaration of a state of rebellion and did

only on August 1, 2003 through Proclamation No. 435

DECLARING THAT THE STATE OF REBELLION HAS CEASED

TO EXIST.

- F4: This case is a consolidation of the cases (GR Nos.

159085, 159103, 159185, 159196) filed before the Court

that challenge the validity of Proclamation No. 427 and

General order No. 4.

- Grounds relied upon by the petitioners:

o That Proclamation No. 427 and General order No. 4 are

unconstitutional:

Sanlakas and PM v. Executive Secretary, et al, G.R. No.

159085.

Section 18, Article VII of the Constitution does not

require the declaration of a state of rebellion to

call out the armed forces.

There exists no sufficient factual basis for the

proclamation by the President of a state of

rebellion for an indefinite period because of the

cessation of the Oakwood occupation.

SJS Officers/Members v. Hon. Executive Secretary, et al

G.R. No. 159103.

Case Digest | Law Journal 2014

Section 18, Article VII of the Constitution does not

authorize the declaration of a state of rebellion.

The declaration is a constitutional anomaly that

confuses, confounds and misleads because

[o]verzealous public officers, acting pursuant to

such proclamation or general order, are liable to

violate the constitutional right of private citizens.

The proclamation is a circumvention of the report

requirement under the same Section 18, Article

VII, commanding the President to submit a report

to Congress within 48 hours from the proclamation

of martial law.

Presidential issuances cannot be construed as an

exercise of emergency powers as Congress has

not delegated any such power to the President.

Rep. Suplico et al. v. President Macapagal-Arroyo and

Executive Secretary Romulo, G.R. No. 159185

The declaration of a state of rebellion... amounts

to a usurpation of the power of Congress granted

by Section 23 (2), Article VI of the Constitution.

Pimentel v. Romulo, et al, G.R. No. 159196

The declaration of a state of rebellion opens the

door to the unconstitutional implementation of

warrantless arrests for the crime of rebellion

(speculative)

- Grounds relied upon by the respondents:

o That Proclamation No. 427 and General order No. 4 are

valid and constitutional:

Executive Powers

Issue:

1. Do the petitioners have standing to file the instant petition?

Case Digest | Law Journal 2014

2. Is the issue moot and academic?

3. Does the President have the power to declare a state of

rebellion?

Ruling:

- R1: Only petitioners Rep. Suplico et al and Sen. Pimentel, as

Members of Congress, have standing to challenge the

subject issuances. To the extent the powers of Congress are

impaired, so is the power of each member thereof, since his

office confers a right to participate in the exercise of the

powers of that institution (Philippine Constitution Association

v. Enriquez). On the other hand, petitioners, Sanlakas and

PM, and SJS Officers/Members, have no legal standing

or locus standi to bring suit for failure to demonstrate any

injury to itself

which would justify the resort to the

Court. Petitioner is a juridical person not subject to

arrest. Thus, it cannot claim to be threatened by a

warrantless arrest. Nor is it alleged that its leaders,

members, and supporters are being threatened with

warrantless arrest and detention for the crime of

rebellion. Every action must be brought in the name of the

party whose legal rights has been invaded or infringed, or

whose legal right is under imminent threat of invasion or

infringement (Lacson v. Perez). Even assuming that

petitioners are peoples organizations, this status would

not vest them with the requisite personality to question the

validity of the presidential issuances. That petitioner SJS

officers/members are taxpayers and citizens does not

necessarily endow them with standing. A taxpayer may

bring suit where the act complained of directly involves the

illegal disbursement of public funds derived from taxation.

No such illegal disbursement is alleged. Moreover, a citizen

will be allowed to raise a constitutional question only when

he can show that he has personally suffered some actual or

threatened injury as a result of the allegedly illegal conduct

of the government; the injury is fairly traceable to the

challenged action; and the injury is likely to be redressed by

Case Digest | Law Journal 2014

a favourable action. Again, no such injury is alleged in this

case. Furthermore, even granting these petitioners have

standing on the ground that the issues they raise are of

transcendental importance, the petitions must fail.

- R2: Petitions have been rendered moot by the lifting of the

declaration. As a rule, courts do not adjudicate moot cases,

judicial power being limited to the determination of

actual controversies. Nevertheless, courts will decide a

question, otherwise moot, if it is capable of repetition yet

evading review. Hence, to prevent similar questions from

reemerging, the court has laid to rest the validity of the

declaration of a state of rebellion in the exercise of the

Presidents calling out power, the mootness of the petitions

notwithstanding.

- R3: Yes. The President, as Commander-in-Chief, has a

sequence of graduated power[s]. From the most to the

least benign, these are: the calling out power, the power to

suspend the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus, and the

power to declare martial law. In the exercise of the latter

two powers, the Constitution requires the concurrence of two

conditions, namely, an actual invasion or rebellion, and that

public safety requires the exercise of such power. These

conditions are not required in the exercise of the calling out

power. The only criterion is that whenever it becomes

necessary, the President may call the armed forces to

prevent or suppress lawless violence, invasion or rebellion

(Integrated Bar of the Philippines v. Zamora). It is equally

true that Section 18, Article VII does not expressly prohibit

the President from declaring a state of rebellion. Note that

Case Digest | Law Journal 2014

the

Constitution

vests

the

President

not

only

with Commander-in-Chief powers but, first and foremost,

with Executive powers.

Moreover,

from

the

U.S.

constitutional history, the Commander-in-Chief powers are

broad enough as it is and has become more so when taken

together with the provision on executive power and the

presidential oath of office. Thus, the plenitude of the powers

of the presidency equips the occupant with the means to

address exigencies or threats which undermine the very

existence of government or the integrity of the State. In The

Philippine Presidency A Study of Executive Power, the late

Mme. Justice Irene R. Cortes, proposed that the Philippine

President was vested with residual power and that this is

even greater than that of the U.S. President. She attributed

this distinction to the unitary and highly centralized nature

of the Philippine government. She noted that, There is no

counterpart of the several states of the American union

which have reserved powers under the United States

constitution. Furthermore, the petitions do not cite a

specific instance where the President has attempted to or

has exercised powers beyond her powers as Chief Executive

or as Commander-in-Chief. The President, in declaring a

state of rebellion and in calling out the armed forces, was

merely exercising a wedding of her Chief Executive and

Commander-in-Chief

powers. These

are purely

executive powers, vested on the President by Sections 1 and

18,

Article

VII,

as

opposed

to

the delegated

legislative powers contemplated by Section 23 (2), Article VI.

Salient Pronouncement(s):

The Presidents authority to declare a state of rebellion springs in the main from

her powers as chief executive and, at the same time, draws strength from her

Case Digest | Law Journal 2014

Commander-in-Chief powers. [Section 4, Chapter 2 (Ordinance Power), Book III

(Office of the President) of the Revised Administrative Code of 1987.]

The mere declaration of a state of rebellion cannot diminish or violate

constitutionally protected rights. Indeed, if a state of martial law does not

suspend the operation of the Constitution or automatically suspend the privilege

of the writ of habeas corpus then it is with more reason that a simple declaration

of a state of rebellion could not bring about these conditions.

Source of Citations:

Philippine Jurisprudence and laws:

o

American Jurisprudence and laws:

o

Other secondary sources:

o

Analysis:

The court did not introduce a new doctrine or principle. It

merely clarified that declaring a state of rebellion is a purely

executive power and not a delegated legislative power.

Decided during Pres. Arroyos term.

Is the Courts ruling influenced by political factors?

No. The courts decision was not in any way influenced by

political factors. The decision was based on the extensive

study and analysis of the nature of the power to declare a

state of rebellion and the scope of the Presidents executive

powers making reference to existing jurisprudence,

academic materials, and the history of the U.S. Constitution.

You might also like

- Corporation Law by Atty Villanueva With Complete Case Digests DiscussionDocument273 pagesCorporation Law by Atty Villanueva With Complete Case Digests DiscussionCharmie Fuentes Ampalayohan100% (5)

- In Re Wenceslao Laureta (Case Digest)Document3 pagesIn Re Wenceslao Laureta (Case Digest)MarianneVitug83% (6)

- Joya Vs PCGG - Case DigestDocument2 pagesJoya Vs PCGG - Case DigestJoanna CusiNo ratings yet

- (A24) LAW 121 - Atlas Fertilizer vs. Secretary of DAR (G.R. No. 93100)Document2 pages(A24) LAW 121 - Atlas Fertilizer vs. Secretary of DAR (G.R. No. 93100)Miko MartinNo ratings yet

- DeFunis V OdegaardDocument1 pageDeFunis V OdegaardRochelle AyadNo ratings yet

- Ople vs. TorresDocument14 pagesOple vs. TorresDeniseNo ratings yet

- Ocampo vs. Rear AdmiralDocument6 pagesOcampo vs. Rear AdmiralYerdXXNo ratings yet

- En Banc (G.R. NO. 164978, October 13, 2005) : Carpio, J.: The CaseDocument8 pagesEn Banc (G.R. NO. 164978, October 13, 2005) : Carpio, J.: The CaseTin SagmonNo ratings yet

- Lopez Vs de Los ReyesDocument2 pagesLopez Vs de Los ReyesJerika Everly Maranan Marquez0% (1)

- IBP vs. Zamora G.R. No.141284, August 15, 2000Document3 pagesIBP vs. Zamora G.R. No.141284, August 15, 2000meme bolongonNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 157509Document10 pagesG.R. No. 157509Klein CarloNo ratings yet

- Constitutional Law 1 - Prof. Alberto Muyot CASE DIGEST For F2021Document2 pagesConstitutional Law 1 - Prof. Alberto Muyot CASE DIGEST For F2021alfredNo ratings yet

- INS Vs ChadhaDocument26 pagesINS Vs ChadhaJin AghamNo ratings yet

- Civil Liberties Union Vs Executive SecretaryDocument2 pagesCivil Liberties Union Vs Executive Secretaryyra crisostomoNo ratings yet

- 20.1 People vs. Gacott DigestDocument1 page20.1 People vs. Gacott DigestEstel TabumfamaNo ratings yet

- CHREA v. CHRDocument2 pagesCHREA v. CHRML BanzonNo ratings yet

- Jimenez v. Cabangbang, G.R. No. 15905, August 3, 1966Document1 pageJimenez v. Cabangbang, G.R. No. 15905, August 3, 1966Jay CruzNo ratings yet

- Bermudez V TorresDocument3 pagesBermudez V TorresAndrea AlegreNo ratings yet

- Sandoval V Hret DigestDocument2 pagesSandoval V Hret DigestJermone Muarip100% (3)

- Lacson Vs Perez Case DigestDocument1 pageLacson Vs Perez Case DigestFeBrluadoNo ratings yet

- Sabio V GordonDocument4 pagesSabio V GordonZy AquilizanNo ratings yet

- People Vs Gacott, G.R. No. 116049Document7 pagesPeople Vs Gacott, G.R. No. 116049Jeffrey TolentinoNo ratings yet

- Javellana VS Executive SecretaryDocument5 pagesJavellana VS Executive SecretaryMA. TERESA DADIVASNo ratings yet

- Aguinaldo V JBC PDFDocument4 pagesAguinaldo V JBC PDFTrisha Dela RosaNo ratings yet

- Sanlakas v. Executive SecretaryDocument1 pageSanlakas v. Executive SecretaryOswald ImbatNo ratings yet

- IBP Vs ZamoraDocument1 pageIBP Vs ZamoraJonathan PacificoNo ratings yet

- Consti Francisco Vs House of Representatives, 415 SCRA 44, GR 160261 (Nov. 10, 2003)Document3 pagesConsti Francisco Vs House of Representatives, 415 SCRA 44, GR 160261 (Nov. 10, 2003)Lu CasNo ratings yet

- Aquino III v. COMELEC (2010)Document1 pageAquino III v. COMELEC (2010)Cristelle Elaine ColleraNo ratings yet

- De Perio Santos v. Executive SecretaryDocument4 pagesDe Perio Santos v. Executive Secretaryjuju_batugalNo ratings yet

- Mabanag vs. Lopez-Vito Et Al. No. L-11123 March 3, 1947Document2 pagesMabanag vs. Lopez-Vito Et Al. No. L-11123 March 3, 1947Angelo Raphael B. DelmundoNo ratings yet

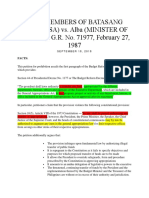

- CONSTI 1 Case Digest Demetria v. Alba, 148 SCRA 208 (1987) TOPIC: Separation of PowersDocument3 pagesCONSTI 1 Case Digest Demetria v. Alba, 148 SCRA 208 (1987) TOPIC: Separation of PowersFidela MaglayaNo ratings yet

- Case No. 394 Lacson-Magallanes v. Pano 21 SCRA 395, 1967Document1 pageCase No. 394 Lacson-Magallanes v. Pano 21 SCRA 395, 1967MarkNo ratings yet

- Republic v. Bayao Et. Al.Document3 pagesRepublic v. Bayao Et. Al.Jazem AnsamaNo ratings yet

- Gudani v. Senga, Case DigestDocument2 pagesGudani v. Senga, Case DigestChristian100% (1)

- G.R. No. 103524, April 15, 1992: Bengzon vs. DrilonDocument1 pageG.R. No. 103524, April 15, 1992: Bengzon vs. DrilonCheryl Fenol100% (1)

- 20 - 556 SCRA 471 - Trillanes v. Pimentel (Re-Election To Office and Criminal Charge)Document2 pages20 - 556 SCRA 471 - Trillanes v. Pimentel (Re-Election To Office and Criminal Charge)Alyanna RollonNo ratings yet

- Garcia V Boi 191 Scra 288 DigestDocument2 pagesGarcia V Boi 191 Scra 288 DigestJJ CoolNo ratings yet

- Avelino Vs Cuenco Case Digest PDFDocument2 pagesAvelino Vs Cuenco Case Digest PDFBeboy Paylangco EvardoNo ratings yet

- IBP v. ZamoraDocument2 pagesIBP v. ZamoraJilliane OriaNo ratings yet

- Plagiarism Mariano Del CastilloDocument3 pagesPlagiarism Mariano Del CastilloJerome Aviso100% (1)

- Belgica V Executive SecretaryDocument2 pagesBelgica V Executive SecretaryPhilip Leonard VistalNo ratings yet

- Texas V JohnsonDocument3 pagesTexas V JohnsonTyler ChildsNo ratings yet

- People Vs GacottDocument1 pagePeople Vs GacottEarnswell Pacina TanNo ratings yet

- Statcon Case Digest: Morales Vs SubidoDocument1 pageStatcon Case Digest: Morales Vs SubidoGenard Neil Credo Barrios100% (6)

- Bengzon v. Drilon G.R. 103524, April 15, 1992Document2 pagesBengzon v. Drilon G.R. 103524, April 15, 1992TrinNo ratings yet

- Dimaporo Vs Mitra DigestDocument3 pagesDimaporo Vs Mitra Digestpawchan02No ratings yet

- Macalintal Vs Pet (2010) DigestDocument7 pagesMacalintal Vs Pet (2010) DigestKar EnNo ratings yet

- Greco Belgica Vs Executive Secretary Paquito OchoaDocument13 pagesGreco Belgica Vs Executive Secretary Paquito OchoaPatrisha AlmasaNo ratings yet

- Philippine Constitution Association Vs Salvador EnriquezDocument1 pagePhilippine Constitution Association Vs Salvador Enriquezlckdscl100% (1)

- In Re LauretaDocument2 pagesIn Re Lauretaarcher2013100% (2)

- Pobre v. MendietaDocument2 pagesPobre v. MendietaEmrico Cabahug0% (1)

- Belgica Vs Ochoa - DigestDocument4 pagesBelgica Vs Ochoa - DigestSamuel TerseisNo ratings yet

- Go Tek V Deportation BoardDocument1 pageGo Tek V Deportation Boardgelatin528No ratings yet

- National Amnesty Commission vs. Commission On Audit (GR 156982, 8 September 2004)Document3 pagesNational Amnesty Commission vs. Commission On Audit (GR 156982, 8 September 2004)adobopinikpikanNo ratings yet

- In RE BermudezDocument1 pageIn RE BermudezSharon_Cerro_6742No ratings yet

- Bagong Bayani Vs ComelecDocument2 pagesBagong Bayani Vs ComelecJen DeeNo ratings yet

- 12 Montecarlos Vs Comelec GR 152295Document1 page12 Montecarlos Vs Comelec GR 152295Van John MagallanesNo ratings yet

- Gloria v. Court of Appeals (2000)Document2 pagesGloria v. Court of Appeals (2000)Amber Anca100% (1)

- Consti 1 Case ListDocument9 pagesConsti 1 Case ListTin PascuaNo ratings yet

- Demetria Vs Alba DigestDocument3 pagesDemetria Vs Alba DigestAnne Camille SongNo ratings yet

- Case #1: The Proclamation No. 427 and General Order No. 4 Are UnconstitutionalDocument93 pagesCase #1: The Proclamation No. 427 and General Order No. 4 Are UnconstitutionalJayco-Joni CruzNo ratings yet

- Divine Mercy BrochureDocument2 pagesDivine Mercy Brochuremaricar_rocaNo ratings yet

- Litany Mary01 PDFDocument1 pageLitany Mary01 PDFmaricar_rocaNo ratings yet

- Business Plan TemplateDocument5 pagesBusiness Plan Templatemaricar_rocaNo ratings yet

- BATCH 1 Division Cases (Bersamin)Document5 pagesBATCH 1 Division Cases (Bersamin)maricar_rocaNo ratings yet

- Philippine National Bank vs. Aznar 649 SCRA 214 Facts: in 1958, RISCO Ceased Operation Due To Business Reverses. With The DesireDocument2 pagesPhilippine National Bank vs. Aznar 649 SCRA 214 Facts: in 1958, RISCO Ceased Operation Due To Business Reverses. With The Desiremaricar_rocaNo ratings yet

- Bersamin CasesDocument6 pagesBersamin Casesmaricar_rocaNo ratings yet

- Villafuerte v. RobredoDocument1 pageVillafuerte v. Robredomaricar_rocaNo ratings yet

- Philippine National Bank vs. Aznar 649 SCRA 214 Facts: in 1958, RISCO Ceased Operation Due To Business Reverses. With The DesireDocument2 pagesPhilippine National Bank vs. Aznar 649 SCRA 214 Facts: in 1958, RISCO Ceased Operation Due To Business Reverses. With The Desiremaricar_rocaNo ratings yet

- Transportation Law NotesDocument13 pagesTransportation Law Notesmaricar_rocaNo ratings yet

- Adriano v. Pangilinan DigestDocument2 pagesAdriano v. Pangilinan Digestmaricar_rocaNo ratings yet

- Gender Discrimatory ProvisionsDocument2 pagesGender Discrimatory Provisionsmaricar_rocaNo ratings yet

- UNCLOS NotesDocument14 pagesUNCLOS Notesmaricar_roca50% (2)

- Salen vs. BalceDocument2 pagesSalen vs. BalceLuis Armando EnemidoNo ratings yet

- ABC Resolution (Daniel Nacorda)Document2 pagesABC Resolution (Daniel Nacorda)Daniel NacordaNo ratings yet

- MJM Invitation Cambridge PDFDocument2 pagesMJM Invitation Cambridge PDFPranshu PaulNo ratings yet

- Registration (Case Digests)Document7 pagesRegistration (Case Digests)Dia Mia BondiNo ratings yet

- Betty J. Vukonich v. Civil Service Commission and The United States of America, Defendants, 589 F.2d 494, 10th Cir. (1978)Document4 pagesBetty J. Vukonich v. Civil Service Commission and The United States of America, Defendants, 589 F.2d 494, 10th Cir. (1978)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Transportation Law Case DigestsDocument9 pagesTransportation Law Case DigestsScents GaloreNo ratings yet

- 27 LA Del Valle v. Sheriff DyDocument2 pages27 LA Del Valle v. Sheriff Dyalexis_beaNo ratings yet

- Coram: Katureebe C.J., Tumwesigye Arach-Amoko Mwangusya Mwondha JJ.S.C.Document17 pagesCoram: Katureebe C.J., Tumwesigye Arach-Amoko Mwangusya Mwondha JJ.S.C.Musiime Katumbire HillaryNo ratings yet

- CIR vs. DOJ DigestDocument2 pagesCIR vs. DOJ DigestKing BadongNo ratings yet

- 7-Pajuyo Vs CADocument4 pages7-Pajuyo Vs CAMaribel Nicole LopezNo ratings yet

- Employment Act KenyaDocument80 pagesEmployment Act KenyaAqua LakeNo ratings yet

- ELENITA BINAY Vs OMBUDSMANDocument3 pagesELENITA BINAY Vs OMBUDSMANJustin Andre Siguan100% (2)

- Request Letter 20143333Document5 pagesRequest Letter 20143333Eks WaiNo ratings yet

- CHEESMAN Vs IACDocument1 pageCHEESMAN Vs IACPia SottoNo ratings yet

- 23 Lozada-Cerezo Vs PeopleDocument1 page23 Lozada-Cerezo Vs Peopledenxolozada100% (1)

- Ecolde Cuisine Manila V Renaud 2013Document5 pagesEcolde Cuisine Manila V Renaud 2013Jorel Andrew FlautaNo ratings yet

- 1.10 Tort Law and Statute Law: X Would Amount To Harassment of A Particular Individual, You Must Not Do X. That Duty IsDocument1 page1.10 Tort Law and Statute Law: X Would Amount To Harassment of A Particular Individual, You Must Not Do X. That Duty IsShalini AriyarathneNo ratings yet

- A.M. No. 02-1-18-SCDocument12 pagesA.M. No. 02-1-18-SCmfv88No ratings yet

- Johannes Schuback v. CADocument9 pagesJohannes Schuback v. CAMartin FontanillaNo ratings yet

- Statutory Construction ReviewerDocument6 pagesStatutory Construction ReviewerMark John Paul Campos100% (3)

- Democracy in Foucault and HobbesDocument23 pagesDemocracy in Foucault and HobbesJosé Manuel Meneses RamírezNo ratings yet

- Fraud Examination Chapter 1: The Nature of FraudDocument11 pagesFraud Examination Chapter 1: The Nature of FraudRahma KusumaNo ratings yet

- Hon Steven Merryday Chief US District Judge Civil Counsel Appointment.Document160 pagesHon Steven Merryday Chief US District Judge Civil Counsel Appointment.Neil GillespieNo ratings yet

- Importance of Consumer Protection Act - DocumentDocument14 pagesImportance of Consumer Protection Act - DocumentProf. Amit kashyap100% (9)

- SEC Opinion Stretching Purpose ClauseDocument4 pagesSEC Opinion Stretching Purpose ClausejanatotNo ratings yet

- High Court Standing OrdersDocument337 pagesHigh Court Standing OrdersRatanSinghSinghNo ratings yet

- Declaration of Supporters of Božidar RadišićDocument2 pagesDeclaration of Supporters of Božidar RadišićcannajoyNo ratings yet

- NSTP 11-Activity No.5Document1 pageNSTP 11-Activity No.5Lin Lin JamboNo ratings yet

- Constitutional Law of India-II CCSU LL.B. Examination, June 2015 K-2002Document3 pagesConstitutional Law of India-II CCSU LL.B. Examination, June 2015 K-2002Mukesh ShuklaNo ratings yet