Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Turner Vs Lorenzo Shipping

Turner Vs Lorenzo Shipping

Uploaded by

mcfalcantaraOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Turner Vs Lorenzo Shipping

Turner Vs Lorenzo Shipping

Uploaded by

mcfalcantaraCopyright:

Available Formats

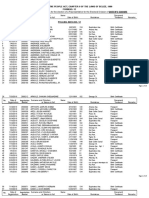

Turner vs.

Lorenzo Shipping

Facts:

The petitioners (Philip and Elnora Turner)

held

1,010,000 shares of stock of the respondent (Lorenzo

Shipping Corp.), a domestic corporation engaged

primarily in cargo shipping activities. The respondent

decided to amend its articles of incorporation to

remove the stockholders pre-emptive rights to newly

issued shares of stock. The petitioners voted against

the amendment and demanded payment of their

shares at the rate of P2.276/share based on the book

value of the shares, or a total of P2,298,760.00.

Subsequently, the petitioners demanded payment

based on the valuation plus 2%/month penalty from

the date of their original demand for payment, as well

as the reimbursement of the amounts advanced as

professional fees to the appraisers.

Respondent

refused

the

petitioners

demand,

explaining that pursuant to the Corporation Code, the

dissenting stockholders exercising their appraisal

rights could be paid only when the corporation had

unrestricted retained earnings to cover the fair value

of the shares, but that it had no retained earnings at

the time of the petitioners demand, as borne out by

its Financial Statements for Fiscal Year 1999 showing a

deficit of P72,973,114.00 as of December 31, 1999.

The respondent found the fair value of the shares

demanded to be unacceptable. It insisted that the

market value on the date before the action to remove

the pre-emptive right was taken should be the value,

or P0.41/share (P414,100.00) and that the payment

could be made only if the respondent had unrestricted

retained earnings in its books to cover the value of the

shares, which was not the case.

Upon the respondents refusal to pay, the petitioners

sued the respondent for collection and damages in the

RTC on January 22, 2001.

The disagreement on the valuation of the shares led

the parties to constitute an appraisal committee

pursuant to Sec. 82 of the Corporation Code. The

committee reported its valuation of P2.54/share, for an

aggregate value of P2,565,400.00.

The respondent opposed the motion for partial

summary judgment, stating that the determination of

the unrestricted retained earnings should be made at

the end of the fiscal year of the respondent, and that

the petitioners did not have a cause of action against

the respondent.

The petitioners filed their motion for partial summary

judgment, claiming that the respondent has an

accumulated unrestricted retained earnings of

P11,975,490.00, evidenced by its Financial Statement

as of the Quarter Ending March 31, 2002;

RTC granted the petitioners motion fixing the fair

value of the shares of stocks at P2.54 per share. The

evidence submitted shows that the respondent has

retained earnings of P11,975,490 as of March 21,

2002. This is not disputed by the defendant. Its only

argument against paying is that there must be

unrestricted retained earnings at the time the

demand for payment is made. RTC further stated

that the law does not say that the unrestricted

retained earnings must exist at the time of the

demand. Even if there are no retained earnings at the

time the demand is made if there are retained

earnings later, the fair value of such stocks must be

paid. The only restriction is that there must be

sufficient funds to cover the creditors after the

dissenting stockholder is paid.

Subsequently, on November 28, 2002, the RTC issued

a writ of execution.

The respondent commenced a special civil action for

certiorari in the CA. CA issued a TRO, enjoining the

petitioners, and their agents and representatives from

enforcing the writ of execution. By then, however, the

writ of execution had been partially enforced. The TRO

then lapsed without the CA issuing a writ of

preliminary injunction to prevent the execution.

Thereupon, the sheriff resumed the enforcement of the

writ of execution.

CA granted respondent's petition. The Orders and the

corresponding Writs of Garnishment are NULLIFIED and

the Civil Case is ordered DISMISSED.

Issue:

WON the petitioners have a valid cause of action

against the respondent.

Held:

No. SC upheld the decision of the CA.

excess of its jurisdiction.

RTC acted in

No payment shall be made to any dissenting

stockholder

unless

the

corporation

has

unrestricted retained earnings in its books to

cover the payment (apply the Trust fund doctrine). In

case the corporation has no available unrestricted

retained earnings in its books, Sec. 83 provides that if

the dissenting stockholder is not paid the value of his

shares within 30 days after the award, his voting and

dividend rights shall immediately be restored.

The respondent had indisputably no unrestricted

retained earnings in its books at the time the

petitioners commenced the Civil Case on January 22,

2001. It proved that the respondents legal obligation

to pay the value of the petitioners shares did not yet

arise. The Turners right of action arose only

when petitioner had already retained earnings in

the amount of P11,975,490.00 on March 21,

2002; such right of action was inexistent on

January 22, 2001 when they filed the Complaint.

The RTC concluded that the respondents obligation to

pay had accrued by its having the unrestricted

retained earnings after the making of the demand by

the petitioners. It based its conclusion on the fact that

the Corporation Code did not provide that the

unrestricted retained earnings must already exist at

the time of the demand.

The RTCs construal of the Corporation Code was

unsustainable, because it did not take into account the

petitioners lack of a cause of action against the

respondent. In order to give rise to any obligation to

pay on the part of the respondent, the petitioners

should first make a valid demand that the respondent

refused to pay despite having unrestricted retained

earnings. Otherwise, the respondent could not be said

to be guilty of any actionable omission that could

sustain their action to collect.

Neither did the subsequent existence of unrestricted

retained earnings after the filing of the complaint cure

the lack of cause of action. The petitioners right of

action could only spring from an existing cause of

action. Thus, a complaint whose cause of action has

not yet accrued cannot be cured by an amended or

supplemental pleading alleging the existence or

accrual of a cause of action during the pendency of the

action. For, only when there is an invasion of primary

rights, not before, does the adjective or remedial law

become operative. Verily, a premature invocation of

the courts intervention renders the complaint without

a cause of action and dismissible on such ground. In

short, the Civil Case, being a groundless suit, should

be dismissed.

Even the fact that the respondent already had

unrestricted retained earnings more than sufficient to

cover the petitioners claims on June 26, 2002 (when

they filed their motion for partial summary judgment)

did not rectify the absence of the cause of action at

the time of the commencement of the Civil Case. The

motion for partial summary judgment, being a mere

application for relief other than by a pleading, was not

the same as the complaint in the Civil Case. Thereby,

the petitioners did not meet the requirement of the

Rules of Court that a cause of action must exist at the

commencement of an action, which is "commenced by

the filing of the original complaint in court."

Additional info:

Cause of Action:

A cause of action is the act or omission by which a

party violates a right of another. The essential

elements of a cause of action are: (a) the existence of

a legal right in favor of the plaintiff; (b) a correlative

legal duty of the defendant to respect such right; and

(c) an act or omission by such defendant in violation of

the right of the plaintiff with a resulting injury or

damage to the plaintiff for which the latter may

maintain an action for the recovery of relief from the

defendant. Although the first two elements may exist,

a cause of action arises only upon the occurrence of

the last element, giving the plaintiff the right to

maintain an action in court for recovery of damages or

other appropriate relief.

Stockholder's Appraisal Right:

Section 81. Instances of appraisal right. - Any

stockholder of a corporation shall have the right to

dissent and demand payment of the fair value of his

shares.

The right of appraisal may be exercised when there is

a fundamental change in the charter or articles of

incorporation substantially prejudicing the rights of the

stockholders. It does not vest unless objectionable

corporate action is taken. It serves the purpose of

enabling the dissenting stockholder to have his

interests purchased and to retire from the corporation.

The Corporation Code defines how the right of

appraisal is exercised, as well as the implications of

the right of appraisal, as follows:

1. The appraisal right is exercised by any stockholder

who has voted against the proposed corporate action

by making a written demand on the corporation within

30 days after the date on which the vote was taken for

the payment of the fair value of his shares. The failure

to make the demand within the period is deemed a

waiver of the appraisal right. (Sec. 82)

2. If the withdrawing stockholder and the corporation

cannot agree on the fair value of the shares within a

period of 60 days from the date the stockholders

approved the corporate action, the fair value shall be

determined and appraised by three disinterested

persons, one of whom shall be named by the

stockholder, another by the corporation, and the third

by the two thus chosen. The findings and award of the

majority of the appraisers shall be final, and the

corporation shall pay their award within 30 days after

the award is made. Upon payment by the corporation

of the agreed or awarded price, the stockholder shall

forthwith transfer his or her shares to the corporation.

(Sec. 82)

3. All rights accruing to the withdrawing stockholders

shares, including voting and dividend rights, shall be

suspended from the time of demand for the payment

of the fair value of the shares until either the

abandonment of the corporate action involved or the

purchase of the shares by the corporation, except the

right of such stockholder to receive payment of the fair

value of the shares. (Sec. 83)

rights of a regular stockholder; and all dividend

distributions that would have accrued on such shares

shall be paid to the transferee. (Sec. 86)

4. Within 10 days after demanding payment for his or

her shares, a dissenting stockholder shall submit to

the corporation the certificates of stock representing

his shares for notation thereon that such shares are

dissenting shares. A failure to do so shall, at the option

of the corporation, terminate his rights under this Title

X of the Corporation Code. If shares represented by the

certificates bearing such notation are transferred, and

the certificates are consequently canceled, the rights

of the transferor as a dissenting stockholder under this

Title shall cease and the transferee shall have all the

5. If the proposed corporate action is implemented or

effected, the corporation shall pay to such stockholder,

upon the surrender of the certificates of stock

representing his shares, the fair value thereof as of the

day prior to the date on which the vote was taken,

excluding any appreciation or depreciation in

anticipation of such corporate action. (Sec. 82)

You might also like

- Linking Novas Files With Simulators and Enabling FSDB DumpingDocument172 pagesLinking Novas Files With Simulators and Enabling FSDB DumpingMarko Nedic100% (2)

- PENA Vs CADocument2 pagesPENA Vs CALiaa Aquino100% (1)

- Turner Vs Lorenzo ShippingDocument3 pagesTurner Vs Lorenzo ShippingWhere Did Macky GallegoNo ratings yet

- 146 - Nell v. Pacific Farms Inc.Document2 pages146 - Nell v. Pacific Farms Inc.MariaHannahKristenRamirezNo ratings yet

- Sulo NG Bayan Vs Araneta DigestDocument1 pageSulo NG Bayan Vs Araneta DigestSimeon SuanNo ratings yet

- PNB vs. Ritratto Group-DigestDocument1 pagePNB vs. Ritratto Group-DigestJessica Joyce Penalosa100% (1)

- Emilio Cano Enterprises vs. CirDocument1 pageEmilio Cano Enterprises vs. CirKen AliudinNo ratings yet

- Shipside Vs CADocument1 pageShipside Vs CARM MallorcaNo ratings yet

- Corpo Law Case Digest Part 1Document13 pagesCorpo Law Case Digest Part 1An JoNo ratings yet

- Aguirre v. FQB+7, Inc. (G.R. No. 170770)Document1 pageAguirre v. FQB+7, Inc. (G.R. No. 170770)Aiza OrdoñoNo ratings yet

- Velarde V LopezDocument10 pagesVelarde V LopezMp CasNo ratings yet

- 17 Lanuza Vs BF CorpDocument30 pages17 Lanuza Vs BF CorpJanine RegaladoNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 203121 - People Vs Sota and GadjadliDocument10 pagesG.R. No. 203121 - People Vs Sota and GadjadliWilbert ChongNo ratings yet

- Padilla vs. CADocument2 pagesPadilla vs. CAEvangeline Villajuan100% (1)

- Tan Vs SycipDocument1 pageTan Vs SycipLG Tirado-OrganoNo ratings yet

- Strategic Alliance Development Corporation v. Redstock Securities LTD., 607 SCRA 413Document41 pagesStrategic Alliance Development Corporation v. Redstock Securities LTD., 607 SCRA 413IamIvy Donna PondocNo ratings yet

- Case Digests On Corporation LawDocument25 pagesCase Digests On Corporation LawGabriel Adora100% (1)

- Bibiano Reynoso IV Vs Court of AppealsDocument1 pageBibiano Reynoso IV Vs Court of AppealsAnonymous oDPxEkdNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 212885, July 17, 2019 - Spouses Fernandez vs. Smart Communications, Inc.Document2 pagesG.R. No. 212885, July 17, 2019 - Spouses Fernandez vs. Smart Communications, Inc.Francis Coronel Jr.No ratings yet

- Mcconnel vs. CA 1 Scra 722 (1961)Document2 pagesMcconnel vs. CA 1 Scra 722 (1961)Jan Jason Guerrero LumanagNo ratings yet

- 931 Terelay-v-YuloDocument3 pages931 Terelay-v-YuloAngela ConejeroNo ratings yet

- Iglesia Evangelica Metodista v. LazaroDocument1 pageIglesia Evangelica Metodista v. LazaroMaria AnalynNo ratings yet

- 51 Bank of Commerce Vs RPNDocument5 pages51 Bank of Commerce Vs RPNDavid Antonio A. EscuetaNo ratings yet

- Strong Vs Repide Case DigestDocument3 pagesStrong Vs Repide Case DigestHariette Kim TiongsonNo ratings yet

- Manacop VsDocument1 pageManacop VsJana marieNo ratings yet

- TMBI vs. Feb Mitsui and ManalastasDocument3 pagesTMBI vs. Feb Mitsui and ManalastasJeffrey MedinaNo ratings yet

- La Campana Coffee Factory V KaisahanDocument2 pagesLa Campana Coffee Factory V KaisahanJued CisnerosNo ratings yet

- 064 Espiritu V PetronDocument2 pages064 Espiritu V Petronjoyce100% (1)

- Mentholatum Co Vs MangalimanDocument2 pagesMentholatum Co Vs MangalimanMaggieNo ratings yet

- Pioneer Insurance Surety Corporation v. Morning Star Et. AlDocument1 pagePioneer Insurance Surety Corporation v. Morning Star Et. AlRenzoSantos100% (2)

- General Credit Corp. v. Alsons Dev. and Investment Corp., 513 SCRA 225 (2007)Document29 pagesGeneral Credit Corp. v. Alsons Dev. and Investment Corp., 513 SCRA 225 (2007)inno KalNo ratings yet

- Strategic Alliance vs. Radstock Securities PDFDocument2 pagesStrategic Alliance vs. Radstock Securities PDFrapgracelim100% (1)

- 10-REYNOSO, IV vs. CADocument2 pages10-REYNOSO, IV vs. CAMaryrose0% (1)

- Corpo - Telephone Engineering v. WCC Case DigestDocument2 pagesCorpo - Telephone Engineering v. WCC Case DigestPerkyme100% (1)

- CUA V TANDocument6 pagesCUA V TANRekaire YantoNo ratings yet

- Pioneer Insurance Corp. v. Morning Star Inc.Document2 pagesPioneer Insurance Corp. v. Morning Star Inc.lovekimsohyun89No ratings yet

- Intramuros Administration vs. Offshore ConstructionDocument43 pagesIntramuros Administration vs. Offshore ConstructionPreciousNo ratings yet

- Angeles Vs SantosDocument1 pageAngeles Vs Santossexy_lhanz017507No ratings yet

- Telephone Engineering vs. WCCDocument1 pageTelephone Engineering vs. WCCAllenMarkLuperaNo ratings yet

- General Credit v. Alsons (D)Document2 pagesGeneral Credit v. Alsons (D)Ailene Labrague LadreraNo ratings yet

- Central Textile Mills, Inc. v. NWPC, 260 SCRA368 (1996)Document4 pagesCentral Textile Mills, Inc. v. NWPC, 260 SCRA368 (1996)inno KalNo ratings yet

- Concept Builders vs. NLRCDocument2 pagesConcept Builders vs. NLRCladyspock100% (2)

- Francisco Motors V Ca G.R. No. 100812. June 25, 1999 FactsDocument1 pageFrancisco Motors V Ca G.R. No. 100812. June 25, 1999 FactsKat JolejoleNo ratings yet

- Francisco v. GSISDocument2 pagesFrancisco v. GSISJoshua Joy CoNo ratings yet

- Corp-Luisito Padilla V CA Feb082017Document6 pagesCorp-Luisito Padilla V CA Feb082017Anonymous OVr4N9MsNo ratings yet

- Sumifru v. Baya - 2017Document1 pageSumifru v. Baya - 2017Dyords TiglaoNo ratings yet

- Tee Ling Kiat V Ayala Corp Et AlDocument2 pagesTee Ling Kiat V Ayala Corp Et Alralph_atmosferaNo ratings yet

- Avon Insurance PLC, Et Al vs. Court of AppealsDocument8 pagesAvon Insurance PLC, Et Al vs. Court of AppealsAngelReaNo ratings yet

- Government vs. Phil. Sugar EstatesDocument1 pageGovernment vs. Phil. Sugar EstatesLe AnnNo ratings yet

- Hyatt Elevators V Goldstar Elevators Full TextDocument4 pagesHyatt Elevators V Goldstar Elevators Full TextanailabucaNo ratings yet

- Nava vs. Peers 74 SCRA 65Document2 pagesNava vs. Peers 74 SCRA 65oabeljeanmoniqueNo ratings yet

- Rich Vs PalomaDocument2 pagesRich Vs PalomaEderic ApaoNo ratings yet

- Cosco Phils Shipping V KemperDocument13 pagesCosco Phils Shipping V KemperErika Galceran FuentesNo ratings yet

- De Silva Vs Aboitiz and CoDocument2 pagesDe Silva Vs Aboitiz and CoAJMordenoNo ratings yet

- McConnell V CADocument1 pageMcConnell V CAPB AlyNo ratings yet

- Associated Bank v. CADocument2 pagesAssociated Bank v. CANelly HerreraNo ratings yet

- 29 - Um V BSPDocument1 page29 - Um V BSPRogelio Rubellano IIINo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 157479. November 24, 2010. Philip Turner and Elnora Turner, Petitioners, vs. Lorenzo Shipping Corporation, RespondentDocument11 pagesG.R. No. 157479. November 24, 2010. Philip Turner and Elnora Turner, Petitioners, vs. Lorenzo Shipping Corporation, RespondentJenny ButacanNo ratings yet

- TURNER Vs Lorenzo Shipping CorpDocument1 pageTURNER Vs Lorenzo Shipping CorpCharm MaravillaNo ratings yet

- Turner Vs Lorenzo Shipping Corp Full TextDocument22 pagesTurner Vs Lorenzo Shipping Corp Full Textkikhay11No ratings yet

- Digests of The Recent Jurisprudence in Corp LawDocument9 pagesDigests of The Recent Jurisprudence in Corp Lawreylaxa100% (1)

- Manansala v. Marlow PDFDocument23 pagesManansala v. Marlow PDFTibsNo ratings yet

- Allied Banking vs. CalumpangDocument3 pagesAllied Banking vs. CalumpangTibsNo ratings yet

- Tolentino NLRC AppealDocument27 pagesTolentino NLRC AppealTibsNo ratings yet

- Aldaba v. CareerDocument14 pagesAldaba v. CareerTibsNo ratings yet

- Affidavit of ConsentDocument1 pageAffidavit of ConsentTibsNo ratings yet

- Affidavit of Adjustment of Area: Republic of The Philippines) City Of) S.SDocument1 pageAffidavit of Adjustment of Area: Republic of The Philippines) City Of) S.STibsNo ratings yet

- Sunit v. OSMDocument5 pagesSunit v. OSMTibs100% (1)

- Aquino Vs DelizoDocument1 pageAquino Vs DelizoTibsNo ratings yet

- Limketkai Sons Milling vs. CADocument1 pageLimketkai Sons Milling vs. CATibsNo ratings yet

- De Leon v. MaunladDocument4 pagesDe Leon v. MaunladTibsNo ratings yet

- IEMELIF vs. NathanielDocument3 pagesIEMELIF vs. NathanielTibsNo ratings yet

- Turner vs. Lorenzo ShippingDocument4 pagesTurner vs. Lorenzo ShippingTibsNo ratings yet

- Salta Vs de VeyraDocument4 pagesSalta Vs de VeyraTibsNo ratings yet

- SBMA vs. UniversalDocument3 pagesSBMA vs. UniversalTibsNo ratings yet

- Sample Dacion en PagoDocument8 pagesSample Dacion en PagoTibs100% (2)

- Salta Vs de VeyraDocument4 pagesSalta Vs de VeyraTibsNo ratings yet

- SRO Contract 2021-2022Document7 pagesSRO Contract 2021-2022inforumdocsNo ratings yet

- Queen's SquareDocument45 pagesQueen's SquareGarifuna NationNo ratings yet

- FanonDocument4 pagesFanonPetronela Andreea Stoian100% (1)

- Araling PanlipunanDocument4 pagesAraling PanlipunanRoland Dave Vesorio EstoyNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3Document4 pagesChapter 3Quyền Nguyễn Khánh HàNo ratings yet

- ATTA Tribe AloDocument8 pagesATTA Tribe AloMarlyn MandaoNo ratings yet

- Commissioner of Internal Revenue vs. ST Luke's Medical CenterDocument14 pagesCommissioner of Internal Revenue vs. ST Luke's Medical CenterRaquel DoqueniaNo ratings yet

- Philippine FlagDocument15 pagesPhilippine Flagmarvin santocildesNo ratings yet

- Horse Racing Manager 2 - UK Manual - PCDocument42 pagesHorse Racing Manager 2 - UK Manual - PCFernando Gonzalez0% (1)

- Payroll and Benefits PDFDocument16 pagesPayroll and Benefits PDFNeha MohnotNo ratings yet

- EDA GuidelinesDocument2 pagesEDA GuidelinesmarcoNo ratings yet

- Kanlahi OrdinanceDocument2 pagesKanlahi OrdinanceJui Aquino ProvidoNo ratings yet

- Judicial Review A Comparative Study VIDITDocument52 pagesJudicial Review A Comparative Study VIDITNazish Ahmad Shamsi100% (1)

- Natl Semiconductor Vs NLRCDocument4 pagesNatl Semiconductor Vs NLRCWonder WomanNo ratings yet

- AFAR. Chapter 5 InstallmentDocument12 pagesAFAR. Chapter 5 InstallmentmacNo ratings yet

- Id China 2023 - Pesquisa GoogleDocument1 pageId China 2023 - Pesquisa GoogleGlayce WolffNo ratings yet

- Rodelas v. AranzaDocument2 pagesRodelas v. AranzaCarlo Columna100% (1)

- Icaew, Valutaion of BusinessDocument4 pagesIcaew, Valutaion of BusinessMujahid ImtiazNo ratings yet

- Immunity To Sovereign PowerDocument42 pagesImmunity To Sovereign PowerDivya JainNo ratings yet

- OS6400 Password RecoveryDocument4 pagesOS6400 Password RecoveryHock ChoonNo ratings yet

- In The Court of District & Sessions Judge, Rajkot Bail Application No. 106 of 2019Document4 pagesIn The Court of District & Sessions Judge, Rajkot Bail Application No. 106 of 2019Deep HiraniNo ratings yet

- An Analysis On Music Entertainment From The Perspective Fourth Year Students of Fiqh and FatwaDocument24 pagesAn Analysis On Music Entertainment From The Perspective Fourth Year Students of Fiqh and FatwaMOHAMMAD NoumaanNo ratings yet

- 4 Egg Crate Grills PDFDocument6 pages4 Egg Crate Grills PDFMUHAMMED SHAFEEQNo ratings yet

- Guidelines and Instructions For BIR Form No. 0619-F (Monthly Remittance Form of Final Income Taxes WithheldDocument1 pageGuidelines and Instructions For BIR Form No. 0619-F (Monthly Remittance Form of Final Income Taxes WithheldMark Joseph BajaNo ratings yet

- 2021 Abejo - v. - Commission - On - Audit20211015 12 33tccu 2Document11 pages2021 Abejo - v. - Commission - On - Audit20211015 12 33tccu 2f919No ratings yet

- New History of KoreaDocument8 pagesNew History of Koreapeter_9_11No ratings yet

- Saint Eustathius of EthiopiaDocument4 pagesSaint Eustathius of EthiopiaHadrian Mar Elijah Bar IsraelNo ratings yet

- ELEM0313ra CebuDocument151 pagesELEM0313ra CebuTheSummitExpressNo ratings yet

- Full Download Solution Manual For Technical Mathematics 4th Edition PDF Full ChapterDocument22 pagesFull Download Solution Manual For Technical Mathematics 4th Edition PDF Full Chapterdecapodableaterl7r4100% (19)