Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Lim

Lim

Uploaded by

Esther van LuitCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Lim

Lim

Uploaded by

Esther van LuitCopyright:

Available Formats

Development of Archetypes of International Marketing Strategy Author(s): Lewis K. S.

Lim, Frank Acito, Alexander Rusetski Source: Journal of International Business Studies, Vol. 37, No. 4 (Jul., 2006), pp. 499-524 Published by: Palgrave Macmillan Journals Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3875167 . Accessed: 19/04/2011 17:43

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at . http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=pal. . Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Palgrave Macmillan Journals is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of International Business Studies.

http://www.jstor.org

of Studies Business 37, journal International (2006) 499-524

of Business rights All reserved 0047-2506 $30.00 ? 2006Academy International www.jibs.net

of archetypesof Development marketing strategy

Lewis KS Liml'2, FrankAcito' and Alexander Rusetski"'3

Schoolof Business, IndianaUniversity, 1Kelley Indiana,USA; Bloomington, 2NanyangBusiness School,NanyangTechnological University, of 3School Administrative Singapore; Studies, York Toronto, Ontario, University, Canada Correspondence: Lewis Lim,Division of Marketingand InternationalBusiness, Nanyang Business School, Nanyang Technological University,S3-B2C-95 Nanyang Avenue, Singapore 679798, Singapore. Tel: +65 6790 4095; Fax: +65 6791 3697; E-mail:akslim@ntu.edu.sg Abstract

international

The extant business literaturecontains three separate characterizations of internationalmarketingstrategy: standardization-adaptation, concentrationhave, for dispersion, and integration-independence.These characterizations alikeof the strategic students, and practitioners decades, informedresearchers, options a multinationalfirm might have in formulating its cross-border have yet to marketingapproaches. Although useful, these characterizations be unifiedwithin an integrativeclassification scheme that considersthe gestalt combinatorialpatterns along multiple strategy dimensions. Towardcreating such a classification of scheme, this paperproposesa holisticconceptualization international theory, whereby marketingstrategygrounded in configurational archetypes.We present evidence of strategiesare viewed as multidimensional three distinctinternational marketingstrategyarchetypesobtained through an exploratorycase coding/clusteringstudy. Afterdiscussingthe characteristics, possible drivers,and contingent performancepotentials of these archetypes, we offer directionsfor future research.

Journal of International Business Studies (2006), 37, 499-524. dol:I0. I057/palgrave.jibs.8400206

standardization adaptation; vs Keywords:international marketing; globalmarketing; cluster case configurations; survey analysis methodology;

Introduction

Classification is especially important to the study of organizational strategies; strategies consist of the integration of many dimensions which, in turn, can be configured in seemingly endless combinations. Without a classification scheme, the strategyresearchermust deal individually with the many variables of interest.., and must generally assume that all combinations are possible. A strategy classification scheme helps bring order to an incredibly cluttered conceptual landscape. (Hambrick,1984, 27-28)

Received: 25 November 2003 Revised: 14 October 2005 Accepted: 2 November 2005 Online publication date: 25 May 2006

For the past four decades, business scholars have sought to characterize and classify the international marketing strategies of multinational firms (Buzzell, 1968; Keegan, 1969; Hovell and Walters, 1972; Ozsomer and Prussia, 2000). Of ultimate concern among these scholars is the performance potential associated with any type of international marketing strategy. A more fundamental goal of classifying these strategies, though, is simply to help researchers,students, and practitioners in the field understand the different strategic options a multinational firm might have in structuring its marketing approaches across country markets. For the most part, the literature has characterized international marketing strategy from one of three perspectives (Zou and

500

International marketing strategy archetypes

Lewis Lim al KS et

Cavusgil, 2002). The most common characterization of international marketing strategy is along the standardization-adaptation dimension (e.g., Jain, 1989). From this perspective, international marketing strategies are differentiated according to the degree of standardization (vs adaptation) pursued with respect to one or more of the marketing mix elements (e.g., product, price, promotion). Thus, a standardization strategy is characterized by the application of uniform marketing mix elements (i.e., product design, pricing, distribution, etc.) across different national markets. Conversely, an adaptation strategy is characterizedby the tailoring of marketing mix elements to the needs of each market. A second way of characterizing international marketing strategy stems from the concentrationdispersionperspective (e.g., Roth, 1992). This perspective, rooted in Porter's (1986) analysis of international competition and most recently reflected in Craig and Douglas's (2000) theory of configural advantage, is concerned more with the geographic design of the international marketing organization. The underlying premise of this perspective is that a multinational firm should seek an optimal geographic spread of its value-chain activities such that synergies and comparative advantages across different locations can be maximally exploited. International marketing strategies, then, are differentiated according to the extent to which one or more aspects of the marketing value chain are consolidated or 'concentrated' at particular geographic locations, vs being scattered or 'dispersed' across various country markets. A third characterization of international marketing strategy is concerned with how competitive marketing activities across country markets are orchestrated. This perspective, referred to here as the integration-independence perspective, is heavily influenced by the competitive 'warfare'description of Hamel and Prahalad (1985). The key question here is whether a multinational firm treats its subsidiary units as standalone profit centers (i.e.,

independently), or as parts of a grander strategic design (i.e., as integrated units). Accordingly, international marketing strategies should be differentiated according to the degree of consultation and integrated action across markets, and the willingness to which a performance outcome in any one market is sacrificed in order to support the competitive campaigns in other markets. Each of the above three major characterizations captures an important facet of international mar-

keting strategy. Specifically, as the standardizationadaptation characterization is concerned with the degree of harmonization of the marketing mix elements, it captures the market offeringaspect of international marketing strategy. In comparison, as characterization the concentration-dispersion deals with the geographical design of the marketing value chain, it captures the structural/organizational aspect of international marketing strategy. Finally, as the integration-independence characterization concerns the planning, implementation, and control elements of competing in a global marketplace, it captures the competitive processaspect of international marketing strategy. Together, these characterizations potentially provide rich descriptions of the ways in which a multinational firm can choose to serve its customers, organize itself, and compete in the international marketplace. Unfortunately, the potential to richly describe holistic patterns of international marketing strategies does not appear to be completely facilitated by conceptual and methodological advances in the field. Until very recently, scholars have relied on unidimensional schemes to discuss international marketing strategies, and/or have discussed them from a single perspective. Forexample, Jain's (1989) treatment of the construct 'marketing program standardization' seems to be a general unidimensional one, with complete standardization on one end of the pole and complete adaptation on the other.1 Likewise, Olusoga (1993) defines and measures 'market concentration' mostly in general terms: that is, without distinction among varying degrees of concentration for different value chain activities. Consequently, one would suspect that students and practitioners exposed to this literature might be, at best, equipped to think of international marketing strategies in terms of simple categorical labels such as 'standardized', 'adapted', 'concentrated', etc., without a deep understanding of what they imply at a holistic level. The recent effort by Zou and Cavusgil (2002) to model the construct of international (global)

marketing strategy represents a significant step toward a truly multidimensional approach to this concept. Zou and Cavusgil (2002) propose a second-order factor construct, termed the 'GMS', which overarches eight first-order dimensions of global marketing strategy spanning the three broad characterizations.2 Thus any multinational firm's global marketing strategy, with given degrees of standardization, concentration, and integration, can be captured by a single GMS score. However,

journal of International Business Studies

International marketing strategy archetypes

Lewis Lim al KS et 501

such a second-order factor construct, while providing an aggregate measure of the degree of 'globalness' of a multinational's marketing strategy, is not modeled to take into account possible interactions among the first-order strategy dimensions. Specifically, by virtue of its linear approach, it is not designed to capture qualitatively distinct patternsof strategy made up of different combinations of strategy elements. This limitation is regrettable because the various strategy elements are likely to interact and combine themselves into multidimensional 'gestalts' (Miller, 1981, 1986; Meyer et al., 1993). All of the above problems point to the need for a more intricate, yet robust, method for describing and classifying international marketing strategies. To that end, we present a holistic and unified approach to viewing international marketing strategy, an approach that is grounded in the configurational theory of organizations (Miller, 1981, 1986, 1996; Meyer et al., 1993), and which sees strategies as multidimensional archetypes. This approach not only takes into account the different ways in which any given international marketing strategy can be characterized (i.e., in terms of standardization-adaptation, concentration-dispersion, and integration-independence), but also considers the overall configurational pattern of the strategy,in terms of its positions along the different dimensions. Thus our approach offers significant advantages over any single characterization of international marketing strategy, or any single aggregate score of the 'globalness' of marketing strategy (Zou and Cavusgil, 2002). To support our conceptualization, we report a case coding/clustering study in which we utilized a taxonomic procedure for uncovering several distinct archetypes of international marketing strategy. Although the results cannot be taken as conclusive because of the exploratory nature of our analysis, the presence of archetypes within a limited sample provides preliminary evidence for the efficacy and theoretic value of the configurational approach. Our proposed approach makes three fundamental contributions to the international marketing literature. First, our notion of strategy archetypes arguably represents the first truly multidimensional way of describing and classifying international marketing strategies. By differentiating strategies in terms of their relative proximities in multidimensional space, our approach provides a novel integrative perspective on the various strategic

marketing options that can be or have been pursued by multinational firms, and allows a more meaningful comparative evaluation of international marketing strategies. Second, beyond identifying strategy archetypes per se, our approach provides a starting point for inquiring into their evolution as well as for a contingent analysis of their performance potential. By virtue of the multidimensionality in their configurational patterns, the archetypes contain rich information about the marketing behaviors of multinational firms and about factors that might contribute to their effectiveness. This presents a valuable opportunity to consolidate our knowledge of international marketing and international strategy. Third, our approach has pedagogic value. By demonstrating the presence of archetypes of international marketing strategies and discussing their contingent performance potential, we bring forth an important set of ideas and a useful framework for future teaching of international marketing. Students and practitioners could then better appreciate the multifaceted nature of international marketing without having to rely on unidimensional labels or dichotomies. The next section of this paper reviews the field's past efforts in characterizing and classifying international marketing strategy,and reiterates the need for a more robust approach to delineating strategies. We then introduce our proposed archetype approach and highlight its foundations in configurational theory. Next, we illustrate the utility of our approach by examining data from our case coding study for the presence of archetypes. Based on the findings, we explore the likely drivers of archetypes and potential archetype performance variations. The study of international marketing strategy: toward a unified multidimensional characterization The marketing literature has dealt with international advertising issues since at least the early

1960s (e.g., Elinder, 1961; Roostal, 1963; Fatt, 1964), but it was Buzzell (1968) who offered the first systematic discussion of standardization as a type of international marketing strategy. A standardization strategy was defined as the harmonization of the various marketing mix elements (e.g., product design, pricing, distribution, etc.) across different country markets. Conversely, a localization or adaptation strategy would be the adoption of a unique marketing mix in each market. Buzzell

Journal of International Business Studies

; 502

International marketing strategy archetypes

Lewis Lim al KS et

(1968) provided several reasons for favoring a standardization policy, including cost savings, consistency in customer dealings, and the exploitation of a universal appeal, and urged multinational executives to consider moving away from the then-prevalent adaptation policy. Following Buzzell (1968), the international marketing literature continued to debate the merits of a standardization strategy. Perhaps the most notable proponent of standardization was Levitt (1983), who argued that diminishing cultural differences across countries due to technological advancements necessitate a global (standardized) strategy that best captures worldwide economies of scale. Other supporters of this view included Rutenberg (1982), Henzler and Rall (1986), Jain (1989), and Zou et al. (1997), who provided various arguments revolving around scale advantage and consistency in marketing planning and actions. On the other side of the debate were scholars such as Boddewyn et al. (1986), Kotler (1986), Douglas and Wind (1987), Ohmae (1989), and Sheth (1986), who variously pointed out the barriers to worldwide marketing standardization, including governmental and trade restrictions, inter-country differences in marketing infrastructure,and local management resistance. The debate between standardization and adaptation remained largely unresolved through the 1990s (see Theodosiou and Leonidou, 2003). More significantly, perhaps because of the intensity and prominence of the debate, the literature in the 1980s and 1990s began to treat standardization and adaptation as fixed alternative options in international marketing strategy. The titles of several articles published during this period (e.g., Samiee and Roth, 1992; Szymanski et al., 1993; Solberg, 2000) suggested that the academic community had come to accept the concept of international marketing strategy itself as falling along a single continuum of standardization vs adaptation. Moreover, several scholars had begun using unidimensional scales to measure variations of international

marketing strategies. For example, in a follow-up empirical study to Jain (1989), Samiee and Roth (1992) used a single index to measure global marketing standardization. Yet a careful reading of the literature reveals that the state of knowledge was also evolving toward a multidimensional view of international marketing strategy. As early as 1969, Keegan (1969) proposed looking at the issue of standardization vs adaptation from both the product and promotion points

of view. He described four qualitatively different strategies, which could arise from crossing the product-standardization-versus-adaptation dimension with the promotion-standardization-versusadaptation dimension. In addition to these four types of strategy, Hovell and Walters (1972) suggested including variations in terms of the other marketing mix elements, such as distribution and personal selling approaches. In the empirical realm, Sorenson and Wiechmann (1975) found that multinational firms vary their marketing approaches across different country markets along as many as 12 dimensions. Finally, Quelch and Hoff (1986) discussed partial vs full standardization as well as partial vs full adaptation along more than 20 dimensions of business functions, products, marketing mix elements, and countries. Notwithstanding the momentum toward a multidimensional approach to describing and capturing international marketing strategies, the preponderance of studies until at least the mid-1980s had really focused only on the market offering aspect (i.e., the marketing mix) of international marketing strategy. However, two streams of research were to emerge to give rise to two additional strategy characterizations - description schemes based on the structural/organizational and on the competitive process aspects of international marketing. As identified by Zou and Cavusgil (2002), the concentration-dispersion characterization of international marketing strategy can be traced to Porter's (1986) 'design' framework. The focus of analysis is on the structuring of value-chain activities (e.g., R&D/product development, aftersale service, logistics and distribution) across international locations. The measurement scale implied by this perspective is in terms of geographic 'concentration' vs 'dispersion' of each of the value-chain functions (Roth et al., 1991; Roth, 1992). Porter (1986) argued that multinational firms should seek an optimal value-chain 'configuration' such that scale and national comparative advantages are exploited, while balancing responsiveness to local needs. More specific to the marketing area, Craig and Douglas (2000) explicated how the spatial configuration of marketing value-chain activities, made up of differential levels, could influence concentration-dispersion the tightness of the operational interlinkages across markets and the development of border-spanning learning and market-sensing capabilities. These outcomes in turn determine the 'configural' advantage of the firm.

Journal of International Business Studies

International marketing strategy archetypes

Lewis Lim al KS et

503

The other emerging characterization, the integration-independence characterization, is grounded in the competitive 'warfare' description of Hamel and Prahalad (1985). This perspective is concerned with the extent to which a multinational firm orchestrates its competitive moves on an international basis and leverages its competitive position in one market to achieve an advantage in other markets (e.g., by cross-subsidizing its competitive campaigns across different countries). In other words, the key issue here is whether a multinational firm treats its subsidiaries as independent profit centers or as an integrated group of business units. Hamel and Prahalad (1985) illustrate the latter behavior with an example about Goodyear retaliating against Michelin's incursion into the US tire market by launching an attack in Michelin's home base, Europe, thereby tying up Michelin's resources and restraining its ability to compete. Such actions require close coordination among different country offices and compromises in country-level profitability. This perspective therefore implies that international marketing strategy should be measured in terms of the degree of integration in competitive moves and decision-making, the integration of competitive response, and cross-unit communication and mutual consultation (Hout et al., 1982; Yip, 1989). Noting the diverse (three-fold) conceptualizations of international marketing strategy, Zou and Cavusgil (2002) made the first important attempt at the turn of the century to unify the concept and develop a measure that reflects its multidimensional nature. They conceived of a second-order factor, labeled the 'GMS' (acronym for global marketing strategy), that incorporated eight firstorder strategy sub-dimensions spanning standardization-adaptation, concentration-dispersion, and integration-independence (one of the dimensions, standardized price, was dropped during their empirical analysis). With the GMS construct, they made it possible to capture the overall 'globalness' of a firm's international marketing strategy using a single score. The limitation of the GMS model, however, is that it is not able to detect the dominant combinatorial patterns in the data, patterns that would reveal the true multidimensional character of international marketing strategies. Furthermore, to use the GMS score alone to account for variations in multinational firm performance may prove causally ambiguous, as several qualitatively distinct patterns of strategy could technically share the same GMSscore. For example,

Table 1 shows two somewhat distinct patterns of international marketing strategy, represented by variations along the first-order dimensions of the GMS model. Using the factor loadings reported in Zou and Cavusgil (2002) as weights, the overall GMS scores computed for the two strategies turn out to be exactly equal. In summary, although the literature has begun to acknowledge the need to integrate and unify the various characterizations of international marketing strategy in order to derive a rich description and classification scheme, existing conceptual and methodological advances have yet to completely facilitate this endeavor. In particular, progress has yet to be made far beyond the use of unidimensional labels such as 'standardized', 'adapted', and 'concentrated', or the use of aggregate scores of globalness, to describe international marketing strategies. The field is still in need of a more sophisticated and robust method for delineating patterns and types of strategy. Strategy archetypes: a configurational approach The configurational theory of organizations (Miller, 1981, 1986; Meyer et al., 1993) supplies the primary basis for conceptualizing our proposed holistic approach to viewing international marketing strategy. Configurational theory holds that organizational effectiveness arises out of superior combinations of strategic and structural characteristics (Millerand Mintzberg, 1983; Doty et al., 1993; Ketchen et al., 1997). In keeping with the configurational perspective, our approach is grounded in the premise that any concept of strategy is inherently multidimensional, and that various elements of strategy can interact or combine differently in multidimensional space. As Miller (1986, 235-236) aptly puts it in his well-noted piece:

The elements of strategy,structure,and environment often coalesce or configure into a manageable number of common, predictively useful types that describe a large proportion of high-performing organizations. The configurations (or 'gestalts', or 'archetypes',or 'generic types') are said to be predictively useful in that they are composed of tight constellations of mutually supportive elements.

Applied to the present context, it is the different 'constellations', or configurations, of strategy elements that make up a 'universe' of international marketing strategies. Thus, to richly describe international marketing strategies, one must look beyond single strategy dimensions for modal combinatorial patterns across multiple dimensions.

Journal of International Business Studies

504

International marketing strategy archetypes

KS et Lewis Lim al

Table 1 Exampleof two combinations of strategy ratingssharing the same GMSscore Strategydimension GMSI: product standardization GMS2: promotion standardization GMS3: standardized channel design GMS4: concentration of marketing activities GMS5: coordination of marketing activities GMS6: global market participation GMS7: integration of competitive moves Total GMS score Firmla 3.86 2.10 0.29 0.78 1.65 2.32 1.29 6.82 Firm2a -0.35 2.14 1.64 -0.64 5.32 1.86 2.63 6.82

aFactorscores for strategy dimensions and for the GMSwere obtained by multiplyingstandardizedfactor loadings reported in Zou and Cavusgil(2002) by corresponding standardized item scores from their original data set and summing up resulting products.

6 5 4

-.2GMSGS Firm 2 2

-uG-Firm

-1GMS1 GMS2 GMS3 GMS4 GMS5 GMS5 GMS6 GMS7 GMS7 GMS6 GMS2 GMS3 GMS4 GMS1

When patterns are distinctive and exemplary, they can be called the archetypes of strategy. When discovered, such archetypes may be represented using graphical snake-like line profiles that chart different degrees of standardization, concentration, and integration among themselves. However, unlike the line profiles used by Wind (1986) and Douglas and Wind (1987) to illustrate variations of international marketing strategy, the archetypes conceived here are not arbitrary line drawings or stylized prototypes. There is an implied assertion that archetypes are theoretically meaningful strategic forms that are at least viable and potentially high-performing, if not approaching the 'ideal' types assumed by Doty et al. (1993) in their study of configurations. Miller (1981, 1986) offers three theoretical reasons for believing that only a few configurational combinations would dominate any given strategy domain. First, from a population ecology perspective (e.g., Hannan and Freeman, 1977), the environment tends to select out unviable, unsustainable, or otherwise uncompetitive strategies, thereby

leaving a limited number of superior strategic options. Second, borrowing from 'gestalt' principles (e.g., Kelly, 1955), organizations themselves tend to be drawn toward configurations of strategy elements that are internally harmonious and mutually reinforcing. Presumably,this could occur either as a result of the organization's own strategic choice (Child, 1972) or through industry mimetic actions and normative pressures (DiMaggio and Powell, 1983), Third, as suggested by studies of organizational evolution (e.g., Miller and Friesen, 1984), organizational change often occurs either in small incremental steps or in 'quantum leaps', implying that many hybrid forms are often avoided or left unexplored. Consequently, even as the study of strategy moves onto a more complex, multidimensional plane, researchers need to deal with only a limited number of strategy configurations out of numerous technically possible combinations. Implementing the configurational approach to the study of international marketing strategy would involve three major steps. First, the specific dimensions that collectively define the concept of

Business Studies journalof International

International marketing strategy archetypes

KS et Lewis Lim al

505

international marketing strategy should be identified. This is in line with the recommendation of Ketchen et al. (1993), who find that configurations derived from theory-based dimensions have greater predictive validity. As the literature accepts three treatments of strategy - standardization-adaptation (capturing the market offering aspect), concentration-dispersion (capturing the structural/organizational aspect), and integration-independence (capturing the competitive process aspect) - these three broad groups of dimensions should be used concurrently to identify international marketing strategy archetypes. Second, a procedure for selecting a suitable sample of international marketing strategies, to objectively quantify these strategies in terms of the three sets of dimensions, and to statistically detect and delineate combinatorial patterns within the sample, should be performed. To demonstrate this procedure, we describe below a structured case coding/clustering methodology used for uncovering strategy archetypes. Third, the derived archetypes should be meaningfully interpreted and analyzed for possible drivers and contingent performance factors. To that end, we examine the background characteristics of our uncovered archetypes and look to the broader international business literature to make predictions about their relative performance. It should be noted that the approach outlined above is closer to the taxonomicapproach espoused by McKelvey (1975) and Hambrick(1984), and used by Miller and Friesen (1977, 1978, 1980), Woo and Cooper (1981), and Hambrick and Schecter (1983) to empirically uncover configurational archetypes of organizational design or strategy. A taxonomic approach is appropriate when extant theory does not yet permit an a prioriidentification of superior strategy configurations (Meyer et al., 1993). However, in more mature domains, where typologies of effective configurations have already been developed (e.g., the typology of Miles and Snow, 1978), researchershave been able to employ a typological or 'ideal profile' approach to test hypotheses about

certain configurational ideal-types (e.g., Gresov, 1989; Doty et al., 1993; Vorhies and Morgan, 2003). Those hypotheses are concerned mostly with the effect of 'fit' among elements of strategy (measured in terms of deviation from ideal profiles) on firm performance. Related to fit is the issue of equifinality among configurations: that is, whether different configurations achieving varying forms of fit can be equally effective (Gresov and Drazin, 1997). In this paper, we primarily pursue a

taxonomic approach to develop international marketing strategy archetypes. Our subsequent exploration of contingent performance issues will, however, leave scope for the future use of the typological approach. Most importantly, our proposed approach serves to address current limitations in the characterization of international marketing strategy. First, our approach represents a significant advancement from the traditional unidimensional way of classifying strategies based on any of the standardizaor concentration-dispersion, tion-adaptation, alone. The integration-independence perspectives archetypes conceived here are multidimensional in nature, and they encompass strategy elements from all three perspectives. Second, our approach differs from Zou and Cavusgil's (2002) second-order factor model in that it permits the identification of gestalt patterns resulting from different combinations of strategy dimensions, as opposed to a single aggregate measure of strategy 'globalness'. Overall, our approach facilitates a more profound understanding of international marketing strategy in terms of holistic combinatorial patterns. Evidence of archetypes: an exploratory case coding/clustering study To demonstrate the utility of our proposed configurational approach, we undertook an exploratory case coding/clustering study, which, we believe, was the first of its kind in international marketing. Our study consisted of two phases. Phase I involved a 'case survey' methodology (Larsson, 1993), also known as the 'structured case content analysis' method (Jauch et al., 1980), to quantify the international marketing strategies of firms featured in a sample of published cases. We believe that published cases are a useful source of data for our research. Even though these cases are written mostly for teaching purposes, they contain factual and detailed information about the practices and strategic designs of actual firms. Such information, having been gathered through tedious fieldwork, is extremely rich and not easily extracted through quantitative surveys. Moreover, case writers normally rely on multiple key informants and archival records to construct the cases (Jauch et al., 1980). Much of the information contained in the cases would have been cross-validated to the extent possible (for prescriptions of case-writing practices, see Corey, 1998; Roberts, 2001). Compared with using other forms of secondary data, such as annual reports, the use of cases also affords the advantage

Journal of International Business Studies

SInternational 506

marketing strategy archetypes

Lewis Lim al KS et

of enabling measures of process variables, that is, variables dealing with the processes of strategy formulation and implementation. Such processes often are not publicly observable but are central to at least one dimension of international marketing strategy (the integration-independence dimension). Finally, with cases, unlike with survey respondents, the data source (i.e., the case documents themselves) resides permanently in our premises. It is always possible to return to the source for clarification of item ratings and/or for exploration of additional items. To overcome the problem of comparability across cases due to different units of analysis and different case types, we select only cases that describe, in a reasonably detailed manner, the actual international marketing strategies of firms at the business unit level at any given point in time. More precisely, each case should: (1) be concerned with the strategic marketing issues of a firm operating in an international environment; (2) relate to an identifiable business unit for which a single, distinct marketing strategy is formulated and executed; (3) report the key aspects of the firm's overall international marketing strategy (as opposed to being focused on a particular international marketing event or decision, or a particular country strategy); and (4) describe an actual, rather than a planned, international marketing strategy that has been in implementation for a reasonable period of time. In accordance with these principles, we developed a case qualification checklist (see Appendix A) and stringently applied the criteria to our selection of cases. Furthermore, for each case selected for coding, we clearly specified the level of analysis at which the coder should interpret the international marketing strategy of the featured firm (e.g., company, product division, or brand level corresponding to a strategic business unit), as well as the

geographic scope of the firm's international marketing strategy (e.g., worldwide or regional). Our case selection process thus generated a sample of exemplars of international marketing strategies that existed at some point in time. To the extent that companies chosen to be featured in published cases are usually notable industry players with a certain level of financial stability and solvency, it can be argued that they are at least

moderately successful adapters in population ecology terms (Hannan and Freeman, 1977). Consequently, taxonomic archetypes found among these companies would represent viable strategic forms. (This does not imply, however, that any of these archetypes is maximally effective. Archetype performance potential has to be examined in relation to contingent fit, a subject we shall address later in this paper.) The process of translating the qualitative descriptions in the case into quantitative measures was facilitated by a detailed coding scheme. Appendix B shows the coding scheme that was used for measuring the international marketing strategies featured in our sample of cases. The coding scheme contained 16 scale items: seven measuring the standardization-adaptation dimensions, five measuring the concentration-dispersion dimensions, and four measuring the integration-independence dimensions of the featured firm's international marketing strategy. Each scale item was an 11-point bipolar scale with extreme descriptors at both ends.3 To ensure that the coders fully understood the meanings of the coding dimensions, we also provided the coders with detailed definition cards for all of the coding scheme scale items and an instruction booklet that they could refer to as they undertook the coding task. Besides rating the scale items, a coder attending to a given case was required to reference particular sections of the case that contained information supporting his/her ratings. In undertaking the assignment of numerical values along various dimensions based on case narratives, the coder effectively replaced the role of the key informant (as in a typical survey) on behalf of the featured firm. We recruited and trained two successive groups of student assistants to serve as coders in our project. All coders were provided with a detailed instruction sheet, thoroughly briefed on the project requirements, and taken through several practice examples of item-coding procedures before being put on an independent trial. After successfully completing the

trial and being debriefed on particular procedural issues and techniques, the coders began a semesterlong coding job. Each week, the coders were assigned specific cases taken from our case pool. Every case was coded by two coders, who subsequently met to compare their item ratings and resolve any discrepancies. We defined a discrepancy as a difference of more than two points on an 11-point scale between the two coders' ratings. Whenever there was a discrepancy, the coders

Journal of International Business Studies

International

marketing

strategy

archetypes

LewisKSLimet al

507

concerned had to discuss their respective reasons for the rating given, come to an agreement regarding the source of the difference (which was usually due to differences in the interpretation of the text), and then voluntarily adjust their ratings to within a two-point difference. Only in rare instances were the coders unable to successfully resolve a discrepant item. In those rare instances, we stepped in and arbitrated the differences by recoding the items ourselves. The above steps executed over an 8-month period resulted in a coded case sample of about 80 cases. Many cases inevitably contained some items that could not be coded because of incomplete information in the case text. To reduce the number of missing values in our data set, we removed cases that did not have at least 10 out of the 16 items coded. The resultant sample came to 51 cases. With this final sample, we executed Phase II of our taxonomic procedure. Phase II of our procedure involved the preparation and analysis of our data set. To prepare our data set for analysis, we first removed five items for which ratings were not given in more than 30% of the cases. For the remaining 11 items, we then imputed all missing values with their respective item means. We believed these two steps collectively helped us maintain the integrity of our data (by focusing only on commonly rated items with fewer missing values) while preserving our sample size (by not having to perform listwise or pairwise

deletion).4

Rescaled CASE Label Daewoo Singer P&G Europe R&A Bailey Loctite Schering DHL Hewlett Nando's L'Oreal PolyGram Haier Citibank Mary Kay Toyota Bausch Gallo & Lomb Rice AG Packard Elseve Classics Brand Num 4 17 7 37 25 49 9 34 38 42 10 40 32 35 39 1 2 31 47 33 44 26 28 16 21 46 13 20 8 18 30 48 3 5 6 51 23 43 Citroen 50 14 Park 24 15 36 22 12 19 29 45 11 Artois 27 41

Distance

Cluster 15

Combine 20 25 -+

0 5 10 +---------+---------+---------+------------

Ben & Jerry's Utex Fike Selkirk Microsoft Montgras BRL Hardy AXA Euro RSCG Nestle ICI Paint Ikea Dendrite Kikkoman Sargan Tesco Carrefour Sony Europa Godiva Europe Henkel Samsung PSA Peugeot Zara Jurassic Disco Supermecados Dunhill Holdings Barco Murphy Brown WebEx Singapore Rochas Benetton Stella Wal-Mart Airlines

To statistically uncover archetypes of international marketing strategy from our data set, we utilized cluster analysis because of the technique's 'unparalleled ability to classify a large number of observations along multiple variables' (Ketchen and Shook, 1996, 453). Following Punj and Stewart's (1983) recommendation, we applied a twostage procedure to cluster-analyze all 51 cases in the data set along the 11 remaining dimensions. In the first stage, the sample was subjected to hierarchical clustering via Ward's method, which generally

produces clusters whose centroids differ maximally based on minimum within-cluster variance. At this point, we relied on multiple criteria as suggested by Milligan and Cooper (1985) and Ketchen and Shook (1996) to determine the appropriate number of clusters in our data set. Based on an inspection of the dendrogram (see Figure 1) and an evaluation of the pseudo-F, the cubic clustering criterion (CCC), and the agglomeration distance-change statistics (see Table 2), either a two- or a three-cluster

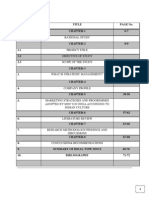

Figure 1 Dendrogram from hierarchicalclustering procedure via Ward's method.

solution seemed acceptable. For example, from the dendrogram, we noted three relatively dense branches, indicating the presence of three 'natural' clusters (Ketchen and Shook, 1996). On the other hand, the statistics favored a two-cluster solution, with peak values of the pseudo-F,the CCC, and the agglomeration distance-change found at two (followed by three) clusters. In deciding between a two- and a three-cluster solution, we therefore considered the interpretability and meaningfulness of each solution (Hair et al., 1998). A two-cluster solution gave very little information, distinguishing clusters as merely high or low along all dimensions. Such a pattern also implied a high

Journal of International Business Studies

508

SInternational

marketing strategy archetypes

KS et Lewis Lim al

Table 2 Pseudo-F, cubic clustering criterion (CCC), and agglomeration distance-change statistics for possible cluster solutions

Statistic 2

Pseudo-F CCC Agglomeration distance-changea 14.49 5.003 644.48

Numberof clusters 3 4 5

8.11 1.953 168.92

10.33 8.67 3.061 2.066 280.00 201.18

(see Figure2). We complement our analysis of these plots with what we call 'pseudo-t' statistics (see also Table 3), each calculated as the absolute value of the ratio of the difference between each pair of centroid values along each dimension to the estimated standard error of this difference (cf. Lattin et al., 2003). Largervalues of the pseudo-t indicate larger differences in centroid values with tighter distributions.6 ArchetypeA This archetype follows a comparatively more standardized market offering policy. Companies grouped under this archetype display, on average, higher degrees of standardization in product design, advertising theme, and pricing as compared with the other archetypes (t> 2.584). On the dimensions of brand name and sales promotion tactics, this archetype is also arguably more standardized than at least one other archetype (t, 3.346). Only on the dimension of channel design is this archetype not evidently the most standardized (average item rating: 5.8). However, this archetype adopts a more concentrated marketing value chain design, in terms of its product design and development (t> 2.349) and advertising and promotional planning functions (t> 3.716). Its logistics and distribution planning function is also more concentrated than that of at least one other archetype (t=4.391). Moreover, this archetype appears to be more integrated in its competitive process in terms of competitive decision-making (t~ 4.655). On the dimension of communication and mutual consultation across country units, this archetype is evidently more integrated than one other archetype (t=3.294). In view of its greater degree of standardization, concentration, and integration, we label this archetype the Global Marketers. The case that is most representative of this archetype, based on the least sum of squared deviations from the cluster centroid, is Godiva Europe (Lambin, 2004), a producer of premium chocolates. At the time of writing, Godiva's international marketing strategy typified what many scholars would regard as a global or near-global strategy. The following quotes from the case illustrate the relatively more standardized market offering policy, especially in the areas of product design and advertising theme (average item ratings of 8.5 and 8.0, respectively):

The Godiva facility in Belgium produces chocolates for the entire world, with the exception of the United States. Products exported from Belgium are identical for all

aEachcolumn refersto the number of clusters priorto the change. Explanatorynotes on the statistics: The pseudo-F statistic is intended to capture the 'tightness' of clusters, and is in essence a ratio of the mean sum of squares between groups to the mean sum of squares within group (Lattin et al., 2003: 291). The value reported is obtained from SASPROC FASTCLUS is calculated as and Pseudo-F=T - P/(G - 1) PcG/(n- G) where G is the number of clusters, Tis the total sum of squares, and PG is the within-groupsum of squares. Largernumbers of the pseudo-Fusually indicate a better clustering solution. The Cubic Clustering Criterion (CCC) was developed by SAS (Sarle, 1983) as a comparative measure of the deviation of the clustersfrom the distribution expected if data points were obtained from a uniform distribution.The criterion is calculated as CCC =In[1 - E(R2)]xK where E(R) is the expected RL, RLis the observed RL,and K is the variance-stabilizing transformation (see Sarle, 1983). Larger positive values of the CCC indicate a better solution, as it shows a larger difference from a uniform (no clusters) distribution. However, the CCC may be incorrect if clustering variablesare highly correlated. The agglomeration distance refersto the distance between clustersbeing merged in each step. A largerdistance indicates highly dissimilarclusters being joined, suggesting that not joining them will preserve the natural structure of the data. As distance-always grows, it is convenient to compare the incremental distance-changes, with a large change indicating that an appropriate solution has been found at the number of clusters priorto the change (Ketchen and Shook, 1996: 446).

correlation among all clustering variables, which we knew was not true. In contrast, a three-cluster solution appeared to offer richer insights into the possible ways various dimensions of international marketing strategy could be combined, thereby illuminating subtler configurational patterns.5 For these reasons, we chose a three-cluster solution. Next, in the second stage of the clustering procedure, the centroid values from the hierarchical clusters were used as seeds in an iterative K-means algorithm to recluster the observations into exactly three clusters. This was to ensure reliable cluster groupings (Punj and Stewart, 1983; Ketchen and Shook, 1996). The final group assignments and centroid values are shown in Table 3. The three clusters now represent three international marketing strategy archetypes. To interpret the clusters, we rely on plots of the centroid values

journal of International Business Studies

International marketing strategy archetypes

KS et Lewis Lim al

509

Different brandname in each market . Product designed for each market Localizedad theme for each market Differentmix of promotiontools in each market Channelstructure

.

Same brandname ineach market Same product in each market Same advertising each market Same sales promotiontools in each market

* I

...

....in

each market Prices set according to situation in each market Each country responsible for product design and development

in unique

1

structure in

Same channel each market Same price position in each market Productdesign and development in a single location Distribution and logistics consolidated at a single location \ Advertisingand promotion planningconsolidated at a single location Marketing planning tightly coordinated across all markets Countrymanagers frequentlyshare

information

"

Each country responsible for logistics and distribution Each country responsible for andadvertising. promotion Each country formulates own marketingplan Countrymanagers do not share

information

. I I .. I

.

[

0 ... 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

Infrastructure minimalists TacticalCoordinators..........

Global Marketers

Figure 2 Centroid values of three archetypes derived from case coding/clustering procedure.

countries, but sales by item are different... Today, the US factory still produces a slightly different and more limited assortment of chocolate pralines. These differences will progressively vanish, and the trend is toward similar production (p. 332). Today, Godiva does not need to make itself known on the international level: Its brand name is already globally recognized. Its current concern, in line with the policy that has been pursued for the past several months, is to create a common advertising message for the entire world (p. 336).

Similarly, the quotes below illustrate the relative high geographical concentration of Godiva's marketing value chain, notably the product design/ development and the distribution/logistics planning functions (averageitems ratings of 8.5 and 7.5, respectively):

The Belgian consumer is the reference point: 'Shouldn't a product that has passed the test of the Belgian consumer, a fine connoisseur of chocolate and a demanding customer, be assured of success throughout the world?' (p. 332). Over the course of the past year van der Veken [President of Godiva Europe, based in Brussels]had completely restructured the company. He startedby firing the marketing and sales staffand then changed the retaildistributionnetworkby removing Godiva'srepresentationfrom numerous stores. He then completely rethought the decorationand design of the remainingstores,and establishedpreciserulesof organization and functioning applicableto those stores (p. 336).

Events described in the case also suggest a tight worldwide (triadic) coordination in Godiva's marketing planning and competitive decision-making process (average item rating: 8.0).

Journal of International Business Studies

Table 3 Clusterassignments and centroid values Case Cluster1: archetypeA Barco Benetton Daewoo Dunhill Holdings Godiva Europe Henkel Loctite Murphy Brewery JurassicPark P&G Europe PSAPeugeot Citroen Rochas Samsung Singapore Airlines Singer Sony Europa Stella Artois Supermercados Disco Utex Wal-Mart WebEx Zara 2: Cluster archetypeB Bausch & Lomb Ben & Jerry's Citibank Dendrite DHL Fike Gallo Rice Haier Hewlett-Packard Ikea L'Oreal Mary Kay Nando's Publisher/source Case number Industry Strategylevel

HBS HBS HBS CranfieldUniv. Kerinand Peterson (2004) HBS HBS UCC HBS HBS Jain(2001) CardiffBusiness School ICFAI HBS HBS IMD Ivey HBS MI ICFAI Stanford HBS

9-591-133 9-396-177 9-598-065 588-002-1 9-585-185 9-594-021 597-029-1 9-596-014 300-085-1 20 594-006-1 503-055-1 9-504-025 9-804-001 IMD-5-0488 9BOOA019 9-599-127 396-160-1 304-1 38-1 SM-121A 9-503-050

Professionalequipment Fashionapparel Diversified Fashion and tobacco Chocolates Diversified Adhesives and sealants Breweries Entertainment Consumer packaged goods Automobiles Perfumes Electronics Airlines Sewing machines Electronics Breweries Grocery retailing Industrialsealing devices General retailing Web-based communications Fashion apparel

ProjectionSystems Division Corporation Automobile business Corporation Corporation Adhesives Group Corporation Murphy brands Licensing business Ariel Ultra brand Corporation Rochas brand Consumer electronics Corporation Corporation Consumer electronics Stella Artois brand Disco supermarketchain Corporation Corporation Web conferencing products Apparel stores

HBS Ivey HBS/Wharton HBS HBS Jain(2001) HBS ICFAI HBS ICFAI CEMS HBS WBS

9-594-056 9A99A037 9-395-142 9-594-048 9-593-011 19 9-593-018 304-264-1 9-501-053 303-112-1 501-011-1 501-012-1 9-594-023 WBS-1999-4

Eye care/lenses Ice cream Banking Sales automation systems Expressdelivery Industrialcontrol devices Rice production and marketing Electricappliances Computers Furnitureretailing Beauty products Beauty products Restaurants

Corporation Corporation Corporation Corporation Corporation Corporation Gallo brand Corporation Home Products Division Corporation Elseve brand Corporation Corporation

Table 3 Continued Case R&ABailey Schering AG Selkirk Cluster3: archetypeC AXA BRL Hardy Carrefour Euro RSCG ICIPaints Kikkoman Microsoft Montgras Nestl Polygram Classics Sargan plc Tesco Toyota Dimension Publisher/source UCD BSE Ivey Case number 501-044-1 303-221-1 9A99M003 Industry Wines and spirits Specialty pharmaceuticals Building materials Strategy level Bailey's brand Corporation Bricksbusiness

W W A

HBS HBS INSEAD IMD IMD HBS HBS HBS HBS HBS CardiffBusiness School HBS ICFAI

9-793-094 Insurance 9-300-018 Wines and spirits 195-001-1 and 195-002-1 General retailing IMD-5-0573 Marketingcommunications GM-557 Paints 9-504-067 Foods manufacturing 9-588-028 Computer software 9-503-044 Wines and spirits 9-585-013 Foods manufacturing 9-598-074 Recorded music 594-047-1 Health care products 9-503-036 Retailing 304-100-1 Automobiles Cluster2 (Archetype B) n= 16 Centroid 8.34 4.25 3.80 3.97 6.15 4.21 6.78 5.45 4.43 4.24 Std dev 1.83 3.11 1.71 1.65 1.79 2.41 2.34 2.31 2.28 1.70

Corporation Corporation Corporation Advertising business Corporation Soy Sauce business Microsoft Works program Corporation Culinary products Corporation Consumer brands division Tesco chain Corporation

W W A W W W W W W W W W W

Cluster1 (archetypeA) n=22 Centroid Std dev 1.56 2.11 1.87 2.00 1.90 2.1 3 1.22 2.23 2.27 1.60

Cluster3 (ArchetypeC) n= 13 Centroid 6.08 3.85 4.65 5.68 2.92 4.28 5.27 3.18 4.80 5.00 Std dev 2.49 3.00 1.79 1.64 1.32 2.80 2.15 1.87 2.37 1.91

'Pseudo-t'statistic A vs B 0.407 3.656 4.856 3.346 0.627 2.843 2.349 1.496 4.449 6.301

Brand name standardization(ST_BRAND) 8.59 Productdesign standardization (ST_DESIGN)7.48 6.67 Advertisingtheme standardization (ST_ADTHEME) Sales promotion tactics standardization 5.96 (ST_PROMO) 5.79 Channel design standardization (ST_CHANNEL) Pricing standardization(ST_PRICING) 6.45 8.23 Product design and development concentration (CONC_PDM) 6.51 Logistics and distribution planning concentration (CONC_LOGDIST) 7.79 Advertising and promotional planning concentration (CONC A&P) Competitive decision-making integration 7.79 (INT_DECISION)

3. 3. 3.

0.

4.

2. 4.

4.

4.

"? 512

International marketing strategy archetypes

KS et Lewis Lim al

ArchetypeB In contrast to the Global Marketers,this archetype pursues a rather mixed standardization policy for its market offering. While its brand name and channel design elements are arguably more standardized (similar to the Global Marketers), its advertising theme and sales promotion tactics are relatively more localized as compared with at least one other archetype (t> 2.529). Along with Archetype C below, its product design and pricing dimensions are also more localized than those of the Global Marketers (t> 2.843). Similarly, its advertising and promotional planning function is more geographically dispersed as compared with the Global Marketers (t=4.449). Nonetheless, its product design/development and distribution/ logistics planning functions are moderately concentrated (average item ratings of 6.8 and 5.5, respectively, in between the other two archetypes). Compared with at least one other archetype, this archetype is also apparently less integrated in its competitive decision-making and communication and mutual consultation (t,>3.143). In view of its selective approach of standardizing only the brand name and channel design with corresponding concentration of product design/development and distribution/logistics functions, we label this archetype the InfrastructuralMinimalists. Companies classified under this archetype appear to emphasize the provision of global infrastructureto their local units with otherwise minimal intervention in the respective local operations and decisions. A case that is representative of this archetype, again based on the least sum of squared deviations from the cluster centroid, is Gallo Rice (Laidler, 1998), featuring the Italian company F&PGruppo, marketer of the Gallo brand of rice. According to the case, the Gallo brand name was used by the company across all country markets, resulting in a brand name standardization average rating of 9.0:

The Gallo brand name and Gallo rooster logo were used consistently across geographic markets... (p. 2).

the fact that the company uses local subsidiaries and agents in different markets, the competitive decision-making process across countries did not appear to be tightly coordinated (average item rating: 3.0). On the other hand, production was concentrated in four countries - Italy, Germany, Argentina, and Uruguay - with apparently centrally controlled product design and development function (average item rating: 7.0):

Focusedon the production of value-addedrice, F&PGruppo described itself as 'the rice specialist' and was one of only a few companies in the world involved in the entire process, from growing and milling to the packaging and marketing of brand rice. The company added value through research and development of new and improved strains of highquality rice, proprietary manufacturing processes, and packaging... A high percentage of the resulting profits were, in turn, reinvested in research and development (p. 1).

However, the exact line of rice sold differed from country to country (average product design standardization rating: 3.0). Similarly, the communication strategy differed somewhat across country markets (average advertising theme and sales promotional tactics standardization ratings: 4.5 and 5.5, respectively). Nonetheless, most sales were made to retailers rather than to institutions (average channel design standardization rating: 7.0). But perhaps because of the nature of the product and

ArchetypeC Like the InfrastructuralMinimalists, this archetype adopts a mixed standardization policy, but in a different way. Although it is moderately standardized in the area of sales promotion tactics (average item rating: 5.7), its product design, advertising theme, pricing policy, and especially channel design are more localized as compared with at least one other archetype (t> 2.584). And, although its average brand name standardization rating is not low (at 6.1), this rating is comparatively lower than those of the other two archetypes (ta 3.166). Its marketing value chain activities, especially the product design/development and distribution/ logistics functions, are also more dispersed (t->2.160). Likewise, its advertising and promotional planning function is clearly more dispersed than that of the Global Marketers (t=3.716). But perhaps how this archetype truly differs from the Infrastructural Minimalists is that it is comparatively more integrated in its competitive process in terms of communication and mutual consultation (t=3.143), even while its competitive decisionmaking process does not appear to be particularly integrated. Because the emphasis of its international marketing strategy is in the coordination (namely, mutual consultation) of tactics (namely, sales promotion tactics) rather than in the standardization of tangible elements such as product designs and channel design, or in the concentration of marketing functions, we label this archetype

the Tactical Coordinators. A case that is representa-

tive of this pattern is AXA: The Global Insurance

Journal of International Business Studies

International marketing strategy archetypes

Lewis Lim al KS et

? 513

Company (Goodman and Moreton, 1995). Like many other multinational insurance firms, AXA pursued a rather localized approach to marketing its products, owing to heavy local regulation of insurance sales:

Insurancewas one of the most heavily regulated industries in the world, with wide variation in the degree and scope of regulation. In general, all countries required that insurers obtain a license to sell insurance... In addition, insurance regulations often stipulated accounting methods and reporting requirements... Insurerswere also limited in the types of assets in which they invested premiums. In a few countries, regulatorsalso strictly controlled premium rates and contract terms (p. 6).

Moreover, AXA'sinternational expansion in the late 1980s and early 1990s occurred mainly through acquisitions, resulting in a complex holdings structure with multiple registered company names in different countries. Hence the average standardization item ratings for product design, channel design, and pricing ranged from a low of 2.5 to 3.0. The concentration of marketing value-chain activities was also apparently rather low (e.g., with an average distribution and logistics planning concentration rating of 3.0), presumably because of the lack of scale economies in sales and marketing activities:

Typically,sales and marketing, along with claims adjusting, represented the two largest cost factors for an insurance company, followed by underwritingand asset management. Of these four activities, only claims adjusting and asset management demonstrated any scale economies. Underwriting and sales were labor intense and generally varied in direct proportion to the volume of premiums written (p. 3).

markets (average sales promotional tactics standardization rating: 7.5). In summary, each of the three derived archetypes exhibits a distinctive configuration of market offering, structural/organizational, and competitive process. The configurations are somewhat complex, with no clear-cut correlations among the strategy dimensions, which means that they would not have been well captured using unidimensional scales or an aggregate score alone. To corroborate the above observation, we performed a descriptive canonical discriminant analysis based on the cluster groupings. Figure 3a shows the positions of the various cases and their respective cluster centroids relative to two canonical discriminant functions or axes. The horizontal axis (Function 1), which discriminates the Global a

4o

0 2o U0 o bC pster B 0 0

K-meanscluster 0 ClusterA B Cluster A Cluster C Centroid [E Group

0o

A Clus-Wr

a

a

o

o

-2 B A

Clustgr a o

-4

-2

0

Function 1

However, what stood out in the AXA case was a moderate-to-high level of competitive process integration, with average competitive decision-making and communication/mutual consultation ratings of 5.0 and 7.5, respectively. The following quote illustrates this pattern:

Still, Bebear'sobjective was to make AXAnot just a French company with foreign subsidiaries, but a truly global organization that would draw on the strengths of every country in which it operated. To implement this objective, he created the Strategy Committee, which would set corporate objectives and oversee their implementation. Apart from Bebear,the group included five senior French major foreign executives.., and five representativesof AXA's operations... The company also began to put into place a common MIS system.., to improve the quality and comparabilityof information in the company (p. 13).

0.8 0.6 0.4 0.2

RI

ST CHANNEL ST BRAND CONC PDM -CONC

LO_(T

0 .2 -0.2

0.3

~

-

CdNC A&P

0.4

0.5

ST

0.6

DESIGN

0.7

0.8

-0.4INT -0.6

CONSULT

04ST

ADTHEME

INTDECISION

Figure 3 Plots from canonical discriminant analysis of cluster

As a result, some of AXA's sales promotional tactics could have been well coordinated across country

to (a) groupings: positionsof cases and centroidsrelative two

discriminant functions; (b) unstandardized coefficients for Function 1 (horizontal) and Function 2 (vertical).

Journal of International Business Studies

) 514

International marketing strategy archetypes

Lewis Lim al KS et

Marketers from the other two archetypes, is positively related to all of the 11 strategy dimensions used in the cluster analysis (see Figure 3b). This appears to be a broad-spectrum function that behaves like Zou and Cavusgil's (2002) aggregate GMS factor. Cases rated collectivelyhigh on the 11 dimensions would tend to be classified under the Global Marketersarchetype. More interesting, however, is the vertical axis (Function 2), which, unlike the GMS factor, serves to further discriminate between the Infrastructural Minimalists (more positive) and the Tactical Coordinators (more negative). This function is positively related to brand name standardization, channel design standardization, product design and development concentration, and distribution and logistics planning concentration, all of which characterize the Infrastructural Minimalists archetype when highly rated. This function is also negatively related to sales promotional tactics standardization and integration of communication and mutual consultation, both of which are characteristic of the Tactical Coordinators archetype when highly rated. Thus, when a firm's strategy does not clearly belong to the Global Marketer archetype (with high values on all dimensions), it will fall under either the Infrastructural Minimalists or Tactical Coordinator based upon the configuration of values it has on the determinants of Function 2. Evolutionary drivers of archetypes Having found evidence of the existence of three distinct archetypes of international marketing strategy, it is appropriate at this point to ask how the archetypes came about: that is, whether there might have been any common exogenous forces imposed on firms belonging to each archetype, forces that have driven their similarity through one or more of the evolutionary mechanisms described by Miller (1981, 1986) - namely, environmental selection, mimetic action, and firm strategic choice. We tried to answer this question by

returning to the cases to look for commonalities within clusters. In keeping with the configurational thinking, we sought to identify holistic sets of exogenous factors as drivers. Because of the qualitative nature of this step, we were limited in our analytical precision. Yet we noted three interesting patterns. First, an inspection of the list of cases classified as the Global Marketers reveals that many of these businesses faced conditions favoring a global

approach to managing their marketing operations, such as minimal or diminishing cultural differences in purchase and consumption behaviors, the lack of or disappearing peculiar local regulations, scale economies in marketing value-chain functions, and the presence of 'global' competitors that required the shared attention of all subsidiary managers. Similar to the construct of 'external globalizing conditions' defined by Zou and Cavusgil (2002), such conditions encourage, or even necessitate, high levels of market offering standardization, value-chain concentration, and competitive process integration. For example, the Sony Europa case (Kashani and Kassarjian, 1998) describes how Sony's European unit was grappling with a set of market forces, including the increasing consolidation of competitors and buyers. Along with the potential for greater cost savings from streamlining operations across markets and the desire to unify the representation of regional interests, this led to the creation of a pan-European marketing organization (treated as a global marketing strategy when the geographic scope of analysis is restricted to the region). Second, an examination of the cases classified as the InfrastructuralMinimalists suggests that many of these companies were involved in product businesses where consumer tastes and preferences differed significantly across countries. Several food companies fall into this cluster, including Gallo Rice, Ben & Jerry's (an ice-cream producer), and Nando's (a fast-food chain), as do a couple of beauty/grooming products companies, namely Mary Kay and L'Oreal. In these businesses, there might also be certain local regulations concerning the production and sale of the product. Thus some of the advantages of standardizing the market offering might not be relevant to these firms. Furthermore, perhaps because of the need to deal with local competitors, a worldwide coordination of competitive processes might not be necessary. Nevertheless, there might still be substantial brand equity effects associated with these businesses, as

demonstrated in the Ben & Jerry's case (Hagen, 1999), where the company frequently used licensing mode to enter foreign markets. Also, there could be established channel and distribution strategies that have worked very well in these industries, as demonstrated by Mary Kay's (Laidler, 1996) frequent use of its direct selling method. These companies therefore could have found it advantageous to provide a minimal brand and channel infrastructure for their international mar-

journal of International Business Studies

International marketing etrategy archetype

KS et Lewis Lim a

) 515

keting operations, but otherwise leave the major marketing decisions to local managers. Third, a look at the cases typifying the Tactical Coordinators points to the possibility that many of market forces that encouraged standardizing their market offering in a major way, but also did not see substantial scale economies in consolidating any part of their marketing value chains. The AXA case mentioned earlier illustrates this possibility. Nonetheless, the similarity of competitive environments, including the presence of shared competitors across country markets, could have motivated these companies to coordinate their competitive decisions and tactics on a worldwide scale. Forexample, several companies, such as Nestle, Euro RSCG,and ICI Paints, faced global competitors even as they operated in local country environments. It might therefore have been critical for these companies to have high degrees of communication and mutual consultation as well as harmonization of competitive tactics across country units. In summary, a combination of environmental factors and market forces appears to drive the type of international marketing strategy adopted by any given multinational firm.

Pla: A configuration environmental marketfactors of and that createsincentivesfor a globalapproach marketing to management,including a high degree of similarityin customer tastes and preferencesacross countries, the absenceof local regulations, presenceof scale econothe mies in operating value-chain and activities, the marketing presenceof global competitors,is likely to engendera

strategy resembling the GlobalMarketers archetype.

these companiesnot only did not experienceany

Plb: A configuration of environmental and market factors that does not particularly encourage a global marketing management approach, including different customer tastes and preferences across countries, existing local regulations, and the need to deal with local competitors, but that at the same time encourages sharing a common brand and channel infrastructure,such as when there are global brand recognition and established distribution strategies, is likely to engender a strategy resembling the Infrastructural Minimalists archetype. Plc: A configuration of environmental and market factors that does not particularly encourage a global marketing management approach, including different customer tastes and preferencesacross countries, existing local regulations, and the absence of scale economies in marketing operations, but that at the same time encourages the coordination of competitive decisions and tactics across markets, such as the commonality of competitive environments and shared competitors, is likely to engender a strategy resembling the TacticalCoordinators archetype.

Archetype performance potential: subsidiary network contingent fit considerations After considering the possible drivers of the different international marketing strategy archetypes, the next question one might pose is: 'Which archetype(s) is/are liable to lead to stronger multinational firm performance?'7This is an important question because, arguably, the ultimate concern for the study of any area of strategy is to explain firm performance variations (Rumelt et al., 1994). (Here, of course, we take the position that performance variations among the archetypes are still likely, even though it has been stated earlier that each of the archetypes is potentially high performing.) However, this is also a difficult question because the relationship between strategy and performance is itself a complex issue. In particular, the implementation context within which a firm operates may influence the effectiveness of any given strategy (Walker and Ruekert, 1987; Noble and Mokwa, 1999). The implementation context imposes peculiar constraints upon the firm, so firm performance is partly a function of how unencumbered the strategy is by those constraints. An important aspect of a multinational firm's implementation context is its network of international subsidiaries,"given that a significant proportion of a multinational's marketing activities is executed (whether or not planned) at the local subsidiary level (Birkinshaw and Morrison, 1995; Solberg, 2000). Research suggests that subsidiary-level factors have the potential to either help or hurt the effective implementation of a multinational's intended strategy (e.g., Wiechmann and Pringle, 1979; Hulbert et al., 1980; Hewett and Bearden, 2001). Therefore, in discussing the performance potential of any international marketing strategy archetype, the characteristics of the subsidiary network need to be considered. In other words, rather than simply order the relative superiority of the different archetypes, it is necessary to examine the contingent fit (Doty et al., 1993) of each archetype with the subsidiary network

characteristics. There are potentially several different subsidiary network characteristics to be considered. These include the scope of subsidiary responsibilities, the level of autonomy held by each subsidiary, the degree of subsidiary dependence on the head office, and the degree of interdependence among subsidiaries. One way to incorporate the effect of these characteristics into the prediction of archetype performance is to model each characteristic as

journal of International Business Studies

516

International marketing strategy archetypes

Lewis Lim al KS et

a moderator of the archetype-performance relationship. Statistically, this involves analyzing the interaction between each characteristic and the various strategy variables that make up an archetype. This is referredto as the interaction approach to studying contingent fit (Drazin and Van de Ven, 1985). However, as Miller (1981) and Meyer et al. (1993) point out, such a 'reductionist' approach is generally aimed at isolating the effects of single contingency variables, and often unrealistically assumes unidirectional linear relationships among the variables. From the perspective of configurational theory, this approach is not ideal for understanding holistic combinatorial patterns of fit between multiple strategy variables and multiple contingency factors. An alternative approach that is more consistent with the configurational thinking underlying this research is to identify configurations of contextual variables that fit well with the respective strategy archetypes. Like the archetypes, each of these contextual configurations is a multidimensional combination of distinct characteristics. This way, multiple subsidiary network characteristics serving as contextual contingencies can be simultaneously considered. Strategy archetypes and contextual contingencies that fit well with each other can be viewed as extended configurations of mutually supportive elements, similar in spirit to Miller's (1986) matching of compatible configurations of strategy and structure. At the same time, when there is a lack of unique one-toone fit between strategy and context, equifinality can be said to exist. While the lack of data prevents a fresh taxonomic discovery of common configurations of subsidiary network characteristics along with an integrated testing of fit with the strategy archetypes earlier uncovered, research on multinational subsidiary behavior has previously identified three configurations of subsidiary roles and structural contexts (Birkinshaw and Morrison, 1995). Because these 'subsidiary roles' and 'structural context' variables appear to broadly describe the nature of