Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Government

Uploaded by

kagvatesanCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Government

Uploaded by

kagvatesanCopyright:

Available Formats

Government's wrong policies behind rupee fall

Story Comments (24)

Read more on US|Rupee|Robin Hood|RBI|India|gdp|dollar|depreciation|Ayn Rand

12 inShare

EDITORS PICK

S&P, Fitch, Moody's under new pressure in Italy Rupee depreciation: Who gains, who loses? Germany, France, Italy vow $163 bn for growth measures Wall Street rebounds after steep drop, banks lead Spain to stress test banks again, focus on seven

By: Himanshu Jain Back in 1957, Ayn Rand, in her magnum opus Atlas Shrugged, showed the world as to what happens when the looting runs dry. When the government starts to trample over the productive society and redistribute wealth, it can certainly make some quick electoral gains but soon the nation is driven out of its vitality and resources; very soon, there is nothing left for the government to redistribute. A sharp depreciation in the currency, falling growth and rising inflation are just some signals towards such a scenario, and to blame it like every other piece of internal economic travesty on some distant western country is an attempt to run away from reality. The Indian rupee has been among the three worst-performing currencies vis-a-vis the dollar in the past one year. That is, indeed, quite an achievement considering that all our south Asian neighbours have done better than us. The recent moves by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), including asking exporters to convert 50% of their dollar holdings into the rupee, would do little in arresting this slide till the fundamental reason behind this fall is not addressed. In fact, this move by the RBI reminds us of an adage, desperate times call for desperate measures, and the fear is that more such capital intrusions can come into play in the future should this slide in the rupee continue. While there can be several factors that can influence the short-to-medium term movement of a currency, on a secular basis, the price of a currency is pretty much dependent on the forces of supply and demand. So, in essence, the increase in the amount of credit net of the actual growth - of real goods and services is what determines the relative value of the currencies in the end. A brief glance at net credit growth - credit growth net of GDP growth - of India and US shows that the net credit growth in India has been almost consistently higher (by a wide margin) than that of US except for a five-year interlude during 2003-07. This fact, as one can see, clearly superimposes itself on the direction of the Indian rupee that depreciates remarkably over this period except for that five-year hiatus. It is, indeed, conspicuous to see the consistent low GDP/credit ratio of India vis-a-vis the US. While the lower productivity of Indian labour can be cited as one of the reasons for this phenomenon, however, this argument can be easily put into question by the outperformance shown by the Indian economy during its 2003-07 heydays. So, clearly, if the lower labour productivity argument does not hold much water, then what could be the reason for this abysmally-low GDP/credit ratio for Indian economy and consequently the state of our currency?

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (120)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

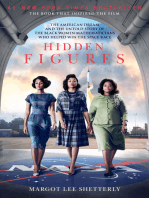

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Indian Stocks Seventh Best Performer Globally For 2012Document3 pagesIndian Stocks Seventh Best Performer Globally For 2012kagvatesanNo ratings yet

- Negative Market Assessment Is Perhaps OverdoneDocument4 pagesNegative Market Assessment Is Perhaps OverdonekagvatesanNo ratings yet

- GovernmentDocument2 pagesGovernmentkagvatesanNo ratings yet

- Shri Ganesha Yan Am AhDocument1 pageShri Ganesha Yan Am AhkagvatesanNo ratings yet