Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Ben Wright Fiction Portfolio

Uploaded by

benwrightdesignOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

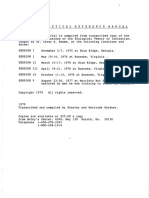

Ben Wright Fiction Portfolio

Uploaded by

benwrightdesignCopyright:

Available Formats

Ben Wright Fiction Portfolio Chorus We didnt want the new neighbors, with their new house and

new oak floorboards and hammering from 6 a.m. to half past 10 every night when they would zip up their sleeping bags and sleep in the sawdust. We didnt want to see their new cars or three chimneys. We didnt want them. The winter was cold, but we still lugged the weeks trash to the edge of the property, inevitably ripping a bag, leaving a trail of wrappers and newspapers and matches in our wake. When the trash piled up too high and the coyotes and raccoons were dragging our secrets to the neighbors lawn, Mama would send us out to burn it. It was here, smoking a cigarette between us and hacking until our vision went yellow, that we got the idea. The vein of anthracite coal, according to the town museums docenta doddering old lady who had lost three husbands to the mines and wore her glasses upside downran from the old mine next to our house down Brushy Pines Road, under the new neighbors house, making a right turn at Shady Oak Drive, underneath every one of the houses in the new subdivision until it reached downtown, where it disappeared for a while before reappearing under St. Ignactius cemetery and continuing due north to Berwick, where it stopped underneath James Howard Taft High. Heck, the docent said, if we dug far enough under our houses, we could stay warm for the rest of her winters. We remembered finding nuggets of coal in our childhood excavations. We remembered dragging it across the bricks of our house into crude pictograms. We remembered the smoldering, coughing fire in our sandbox until Daddy saw the smoke and stomped it out. Hey there, the neighbor said as he approached the mailbox one Thursday. He had a bowtie and an accent. We stared. Thought wed invite yall over for dinner tomorrow night. Hows that sound? One of us nodded, but no one fessed up to it later. The neighbor got his mailtwo letters from Ohio, a bill from the newspaper, and a pamphlet

Ben Wright Fiction Portfolio about fertility solutionsand went inside. Upstairs, a curtain nudged to the side until we disappeared over the hill to the old mine. The trash pile was growing. Every morning we put a fresh layer of lye on top to keep the animals away so Mama wouldnt make us burn it, yet. The neighbors dining room table was a door on two sawhorses that leaned precariously when we pressed down on it. The neighbors elbow kept knocking the doorknob when he passed the potatoes. His wife asked questions that hung in the air like a sickness. We asked her if she was flushed because she was pregnant or afraid. The neighbor poured himself another glass of wine, then another. We asked if we could smoke, but we didnt have any cigarettes. We ate five bites of their stringy roast and all of their carrots. The neighbor asked how the soil was for growing round these parts. We asked if we could dump his trash in the old mine, how it would save him in the long run, how we wanted to just fill it up, after what it had done to our Pa in 57. On trash day, we would get up early and drag the neighbors trash to the mine. The pile was getting higher. One of us shot a coyote, and one of us threw its body on the pile. We tripped over each other to get out the door the next Sunday, as Mama, on the couch as usual, held the book of matches limply in her hand. We were out there for hours as the fire burned through the layers of trash we had collected. We let the smoke surround us and soot pile up in our nostrils. Somewhere, near the top of the pile, the fire had taken to the rock. Somewhere, the fuse had been lit. All we had to do was wait. It started to snow. Later, the front half of the house started to tilt forward. Mama rolled out of bed one night. It took two of us to pick her up and another two to set her bone in a splint made from her rocking chair. The carpet creased and we had to lug the refrigerator to the other side of the kitchen. Lemons rolled to the end of the counter. The pipes burst a few years later. Eight months later, we watched from the windows as the neighbors wife tore open the front 2

Ben Wright Fiction Portfolio door, ripping at her hair and clawing her husband. We watched the ambulance roll up, in no hurry. We watched the medics bring out their baby, bright pink, putting it gingerly in the ambulance. The neighbors didnt come back for a week, but they did. That night, four of us saw Daddy limp down the hall and go into the bathroom. A city inspector came to the door a week later, serving an eviction notice. Theres been a fire, he said. Underground. The carbon monoxide levels here are five times the lethal limit. We stared past his head at the steam rising from the seams of the road. A cat was lounging on the asphalt. Mama screamed from upstairs. Well take it into consideration, we said. Thank you. Breathing felt more like swimming. The air was thick and syrupy. We moved glacially, slowing down to a crawl. Later, after we watched the sinkhole open and swallow that kid whole and the neighbors house collapsed and burned and Main Street split and Mama passed and burned and half the houses in the Shelter Creek subdivision ripped at the seams and the cloud of toxic gas killed all the flowers in the cemetery, the inspector came back, wearing a gas mask. We watched him step through the sigh of our house, sinking into the carpet, kicking the soggy foundation. A meter at his hip squealed. We huddled in the kitchen as his flashlight beam swept over us, barely pausing. We saw Daddy come into the kitchen and scream noiselessly at the intruder before sinking into the ground. We watched the inspector push through the crumbling back door and trek through the overgrown backyard, to the edge of the old mine. Steam was rising somewhere in the distance. Somewhere else, the neighbor gasped for breath on his way to the mailbox. The inspector wrote something on a clipboard. One of us rubbed a match on our hands. We watched, and waited for the fire.

Ben Wright Fiction Portfolio Mooncalf Six months after our wedding, after we sat down in our silent house, my wife is pregnant. We are joyful in doing exactly what we are supposed to be doing for ourselves. I go to work, smiling but worried; she goes, aglow and full of secrets. She is by far the happiest employee there. I answer my office phone as if I am expecting each call. When I tell customers I have to check on the computer, I am looking up their names on baby name websites. I smile at them. They smile back. Okay, I look up from the screen. We just might be able to work this out. When I come home, she is usually doing yoga in the living room, watching talk shows. I sit like an audience on the couch. I felt her kick today, she says brightly. Her arms are a circle, her body contorted, belly pushing up diminutively against her shirt. Lovely, I smile at her. It could be a boy. At night I whisper to her belly and go to sleep. My wife snores when she sleeps on her back but I don't push her over in the middle of the night. I watch her flat stomach and feel the mass building. The doctor, ancient, says everything is going all right. He puts his hands on her middle and I am jealous for a second. He sticks needles in her, calculating. Putting his ear next to her unpopped navel, he frowns. There's not enough humming. My wife looks at me and shrugs. Neither of us have read about this. He leaves before we can ask him anything else. The nurse leads us to where we pay and tells both of us to take folic acid, that recent research suggests that the health of the father is just as important as the mother's. Stay positive, she says. You pay at this window right here. (I have a recurring dream of my birthday. I open present after present, opening each box enthusiastically. Inside are deformed babies wailing for their mothers. Harlequin babies with cracked bleeding skin ruin the carpet, cyclopean infants gurgle spit bubbles onto my shirt, tridactylics grab me with lobster hands.) I wake up and feed my wife vitamins. Her stomach resonates a low C some nights, but usually there is a hollow silence. She tells me that fingerprints are etched onto the skin as the baby feels the 4

Ben Wright Fiction Portfolio capillaries of the uterus; that sadness creates whorls; happiness, spirals. I'm on baby names that begin with S when my wife calls me at work. She speaks slowly, trying to be calm. John. I can't think of anything to say. Something went wrong. I can't stop bleeding. When I get to the house platelets are floating in the foyer, following eddies in the air. The atmosphere is thick with them. I follow crimson rivulets to the bathroom where she's sitting on the toilet staring at a liver blossoming on the tile. It looks like a painting. This liver, the size of a quarter, exhales blood exquisitely. She has been crying but she's stopped. I was brushing my teeth, she says. When it fell out of me. I pick it up delicately and wrap it in a paper towel. I guess we should go to the hospital, I say, trying to be helpful. Are you all right? She bursts into tears again. It's been ringing for hours. It's then that I notice the sound, almost like tinnitus, leaking from her belly. In the car, the paper towel sits between us, heavy and soaked in a pale yellow loss. We tell the nurse our emergency in hushed tones. Someone behind us in line groans deeply in pain. Blood starts to float up from my wife's skirt, mixing with the chemicals in the air. We sit on the plastic bench, expectant, for hours, passing the towel between us when it gets too hot. When the ER doctor finally sees us she hasn't bled for hours. We present him the paper towel, which is flaky. He opens it like a Bible and looks up at us, squinting. What, exactly, are you trying to pull here, he begins, breathing deep. My wife's shoulders begin shaking. I put my arm emptily around her and stare at the clock behind the doctor's head, swallow, and feel hopeless. She finally speaks in a whisper. That came out of me. Mrs. Tofts, I don't know what to tell you. I don't know what you are doing behind closed 5

Ben Wright Fiction Portfolio doors, but having animal organs in your body is not healthy, or, obviously, natural. He balls up the paper towel and tosses it into the trash can. I can't prescribe you anything because you're pregnant. (Not that I think there's anything to prescribe here, except maybe lithium.) Is the baby still humming? The doctor meets her eyes for a second and decides to ignore the question. Good luck getting an obstetrician at this hour. Make an appointment. The veins on his hands are green in the light and he scribbles on a piece of paper. And then we are in the car again, cavernously quiet and impossibly dark. It has been this way since the moon drifted away, inch by inch year after year until it became unintelligible against the constellations, cold as everything. The car takes forever to heat up. I can see my breath slink out of my lungs and stick to the windows. It all starts when the damn thing won't get out of the way, flattening itself underneath my tires. My wife begins wailing almost immediately, hitting me and screaming that we can't kill again today, not on her watch, stop, stop, stop. I whip the car over but we get out slowly, approaching the body. The whole road blinks red on and off. My wife picks up the rabbit's mangled body and bunches up the fur in her hands, grinding her teeth. I watch, noticing something with each red flash. Guts are leaking out of its mouth, and a yellow eye has popped out and rests on the ground. The door of the car dings melodically, and the back of the eyeball looks like a miniature planetarium. Hair falls out in clumps. When we get home my wife rips the sheets off our bed and slams them into the washer. We lie on an empty mattress for the next hour and a half and sigh when we slip into the steaming bed. That night I rub her silent belly in false mourning, wondering if her insides are like an empty church, or an amphitheater in June, if the echoes of whatever was left of our baby made sounds in the dark, and what it would do in the light. Days later, my wife confesses to me that the rabbit stalks her, that when she turns around while 6

Ben Wright Fiction Portfolio she brushes her teeth, foam flowing out of her mouth and plopping into the sink, she can see it standing in the hallway, sentinel of the dead; that it trips her in the dark, sitting on her chest and sniffing out her soul, that she felt whiskers scrape across her face as she slept, that it was all she could think about, that it will steal our baby. (Once, when I was seven, I woke up in the middle of the night and heard screams. I was at my father's house, where the bullfrogs and crickets kept me up until I could no longer fight the sound. It took me a while to locate the source of the screams. The moon was still close then but was a dying lantern and I could barely make out our dog, a big black mangy thing that usually smelled like whatever dead thing it had rolled in that afternoon digging near the edge of the yard, its tail wagging slowly. A brown mama rabbit sat on the other end of her burrow, watching the massacre, just wailing. The dog had found the rabbit's hole and was exterminating her kits one by one. The neighbors on either side of our yard opened their windows and stared at the bloodbath. The mama rabbit cried until my father scared it off with a shotgun blast into the trees.) She refuses all food for a while, claiming she could feel the rabbit's crushed body between her teeth or a yellow eye resting on her tongue. Finally, I get her to accept spinach that she strips of its leaves using her teeth. She nibbles on a piece of lettuce as I heat up soup. You gotta eat, I plead. For the baby. I watch her staring at clover on her way to the mailbox. She's barefoot, ankles swollen with extra weight. She stands ponderously, and then moves on, forgetting about the mail, wandering inside when the sun is covered by clouds. We forget to call the OB the next day, and the next. I barely look at her stomach until she calls me at work, sobbing with relief, putting the phone to her stomach which is trilling like a songbird, whistling beautifully into the void. I call the ancient doctor and he makes an appointment for a house call as soon as he can find his glasses. The next morning, hours before my alarm is set to go off, my wife runs her fingers through my 7

Ben Wright Fiction Portfolio hair, a weary signal. I am still half asleep, and so is she. Sometimes she reaches for me blindly in the night. We begin our old routine, moving delicately around her belly, trying not to disturb what is orbiting inside her. We exhale sighs in turn, fogging each other's skin. I uproot clover in her hair, and dirt stains the pillowcases and her tongue tastes like metal. She murmurs into my shoulder, I'm sorry, then she pushes me off and her belly whistles until I go to take a shower. The doctor comes a few hours later just as the sun looks like it's going to burn the trees, wearing sunglasses. Immediately he asks for a sheet. We scurry around the house obediently, afraid that our slightest misstep will worsen the prognosis. Immediately, the sheet goes up like a flag and down slowly, chasing ghosts out of the dining table. The doctor and I sit on opposite ends of the table, diners. My wife removes her dress and lies between us, legs open to him. I stroke her hair, which is a little greasy. In my peripheral, her belly rises like a secret inside her. With his sunglasses on, we can't tell where the doctor is looking. He begins an interview first: When did this organ fall out of you? His voice is determined yet dreamy, like he is deciding something very important all the time. My wife's voice is coming from her hair. Three, four days ago it must've been now. I was brushing my teeth there was this hollowness all of a sudden. And why didn't you call me immediately? As your primary physician I need to stay abreast of everything that happens to you. He begins sticking fingers inside her, putting his ear close so his head temporarily disappears from my vision. You know, your mother's pregnancy wasn't a walk in the park either. In utero, you were tonally all over the place. He stops, remembering the sounds. We wait a few seconds, not sure if he is done. Yesterday my baby whistled, doctor. It doesn't matter, he snaps. For all you know it could be dead inside you right now. If the note was a low D, that can be attributed to the exhalation of the baby's first breath, which would be the 8

Ben Wright Fiction Portfolio dying breath in this case. The doctor looks at us, we think. We stare back. Mary, you really should have called sooner. My wife's legs start to sag in defeat. I wish I could think of something to say defend her, or us. I sigh instead. The doctor rummages in his bag and emerges with a stethoscope that he breathes on before putting it near her bellybutton. A few seconds later he looks up, annoyed. Hold your breath please. A glance at me. You too. There's a moment of anticipation. My lungs begin to burn, and I try to sneak in a breath through my nose, and I see the doctor's nostrils flare slightly and his jaw clench. The air feels soupy. He coughs once, twice. We begin to breathe when the doctor begins, speaking quiet: There's a heartbeat here. The stethoscope slides over a vein. And here. The metal makes latitudes around her stomach which seems big as anything. Here, here, here. It's like a refrain. Here, and here. he takes off his sunglasses and puts them absently under the bridge of her thigh. There may be more, but they are all beating in tandem, and some might be underneath. It's hard to tell. The creaking of their bones sounds like a forest at night. Closing his eyes, he listens for a few more seconds before deciding. No, not at night. Anyway. Whatever is in in there is spinning slowly. he sits back in the chair, closing his eyes before standing up and grabbing for his hat. I can't do anything more for you, I'm sorry. Get plenty of rest, and whatever happens, get rid of it as soon as you can. Go to the hospital if there's a lot of blood. He swallows hard, then moves to the door, pausing as he grabs the doorknob. Call your mother. And then he is gone. The doctor's car rattles as it drives, and he raises a hand after pulling out of the driveway. We can hear the car for a while as he winds out of the subdivision. We don't say anything for a while. I wander to the bedroom and sit on the unmade bed. I hear my wife unhook the phone, hesitate, then dial. Her voice is quiet, measured. Mom. Something's the matter. My mother-in-law lives in a trailer in the Texas desert, hitting the television for hours until a 9

Ben Wright Fiction Portfolio weak signal arcs across the sky and Catholic Mass flickers in and out. At night, St. Elmo's fire crackles across the metal walls of the trailer. From a thousand miles away, she shouts across the distance, but it is merely chatter from two rooms away. A priest? Mom, that's really not necessary. I'm not even a member of any church. She's starting to sound upset. I close my eyes and lie down on the bed. Her mother yells something out of the phone. No, please please don't do that. Please, mom. Please. I can hear her starting to cry. She hangs up the phone abruptly, and her mother doesn't call back. When I open my eyes my wife is standing in the doorway. I try to smile at her, but fail. We follow separate orbits around the house for the rest of the night, not talking to each other. The sheet stays on the table until a draft blows through and it slips off, making a mountain range on the oriental rug. Neither of us pick it up, and when we turn off the light it is the darkest thing in the room. I kiss a mole on my wife's back before going to sleep. Later that night I wake up to the far-off crescendo of the toilet tank filling then hissing into silence. Then a garbage disposal and my wife sobbing. When she gets back to bed, composed, her belly intact but there is a void between her legs. I get out of bed and strip the sheets off. She curls into a ball and I pull the comforter over her. Until I go to sleep, she is whispering to her belly. We are running out of clean sheets. My wife doesn't get out of bed the next day, and I am awakened by her stomach singing hymns which sound contained beneath layers of muscle. She whispers to me during a pause between hymns, I think the priest is coming today. It is her turn to try to smile. We wait for the priest the rest of the morning, unable to think because of the music. Failing to hear him pull up, we both jump when the doorbell rings and stare at each other for a beat before I stand up and answer the door. The priest smiles at me, at least 8 inches above me and 10

Ben Wright Fiction Portfolio skeptical. I love this one. he hums in tune with my wife's belly. Stepping inside, he looks around for a stereo and realizes where the music is coming from. The smile freezes on his face. Your mother called, he begins, grasping the knots around his waist. We can barely hear him over the singing from her stomach, but don't have anything to say to him. The priest swallows, then coughs once, twice. His eyes close and the priest leans against the doorjamb. he makes a tiny sound, almost a squeak. She said that you needed God. The room begins to swim and the light becomes molasses until the priest coughs again, opens the door, and leaves. Later, on speakerphone he is more verbose: God has blessed all of us in different ways. This pregnancyyour pregnancyis a gift, think of it like that. Everything, everything is for the greater Glory. May God bless your family, Mary & John. We'll be praying for you from here. If he says anything else, we can't hear it as my wife has her first contraction and the singing is reduced to a slow rumble, a far off train. Her water breaks a few hours later as we sit in the living room, waiting for something to happen. When it does, the whole house is filled with a noise like an ice sheet breaking. I put our last clean sheet under her, lavender and musty, smelling like an attic. The first rabbit born is a fetus, deformed and an angry raw pink. It does not move and floats to the top of the water every time I try to flush it down. I spit into the bowl and it goes down on the fourth flush. My wife begins to cry out regularly as the sun goes down, and I walk slowly around the house, turning on lamps, wondering if I should do the fatherly thing and say goodbye to silence, wondering if the world will look different tomorrow. When I wander back into the living room, my wife is holding an infant rabbit which squeaks and shudders, glistening in the afterbirth. Her eyes are red, and the room is jarred with a knocking sound with each contraction, which are coming closer and closer. I close the curtain as another rabbit emerges, its nose opening to let the world in. Another two follow. They stretch their muscles in the 11

Ben Wright Fiction Portfolio light, mostly pink but some have patches of fur. Blood soaks into the couch. I try to tell my wife this but another violent bang cuts me off. The next rabbit to be born is dead and a flower blooms on the couch. I pick up all the rabbits and walk down the hall, dazed. My wife shouts for me, John? John? Where are you going? All five of the rabbits fit in both my hands. I stop by the bathroom and put them in the sink. One of them whimpers, and another opens its eyes and looks directly at me. I turn the water on. My throat swells up and my ears begin to burn. I turn off the light and go back to my wife. She grabs my hand and squeezes, clenching her teeth so hard I hear them snap and she groans. Two more rabbits, umbilical cords wrapped around each other, kicking wildly. The ringing starts again, louder and more intense than ever. Another rabbit, and my wife screams in frustration, teeth falling into dust. When the smell of the room hits me, I just want to be outside: blood and sweat and heat, a mine. The tied-together rabbits have stopped kicking, and the whole world is silent for a few seconds. My wife's breathing gets heavier as she passes out. I pick up the rabbits and head outside, perspiration evaporating in the cold. I look up, wanting to be in a glacier while trying to figure out which of the stars is the moon. The rabbits shiver and I rest them on the patch of clover in the yard. One squeaks as I walk away, but I ignore it. The light of the house comes out from behind the curtains. She is still asleep when I come back inside. Another rabbit sits on the soaked couch, alert and new. I go into the kitchen and grab a dish towel, a bowl, and the telephone, and make a nest, putting the last rabbit inside, swaddling it. Its heart thumps against thin skin, blushing with the anticipation. I dial my mother-in-law. She picks up on the tenth ring, a little breathless and muffled, mouth full: Sorry, darling, I was receiving the Eucharist. Once again, she's yelling into the phone. I can feel the sun beating her trailer into dusk; the painted sky; long shadows; my in-law looking out her smudged window; wondering if it's the glass or her glasses that's dirty; reminding herself to water her wisteria; trying to hear my voice over the buzzing of the phone, the desert, the distance. 12

Ben Wright Fiction Portfolio We're going to be fine, Martha. Everything is just fine. Those prayers really must've worked, thanks. My wife cries out and I regret making this phone call. Lovely! she cries. Marvelous! It might take a few pregnancies for it to catch, dear. It did for me at least. Don't get discouraged over a miscarry. It's all part of the plan. Wonderful. Do remember to write, and tell Mary I'll send that recipe as soon as I can find it. She hangs up, anxious to watch the end of Mass. I lock the front door and turn off all the lights in the house. I pick up my wife and the bowl and put both on the bed and wrap myself around them. She groans in her sleep, and her flat belly creaks. The rabbit is stiff by morning, and when I wake up the house is silent.

13

Ben Wright Fiction Portfolio

Humidifying My middle daughter is leaking out of every pore in her body. She's steaming because she's running a fever, and the entire bedroom is hazy. When I roll her over so she can breathe, and she attempts to speak, it's just gurgling. (Later, when she becomes a hurricane and I stop chasing her, I gargle water, attempting to make every possible sound to try and decode what my daughter might have said. I like to think that it was terribly important, like, Daddy, everything is flowing out of me, or maybe Daddy, I love you.) Before I close the door and call the doctor, my daughter might be crying, though I can't tell because of all the water, but she looks oddly peaceful, and the door doesn't close easily because the carpet has curled up on account of a small stream of water beginning from the bed of her fingernail on the ring finger of her left hand. The next day, my daughter is a Category 2 hurricane knocking down every stalk of immature corn in the tri-county area. I deduce that she escaped through the tiniest crack from where I had attempted to close the window the night before. She vaporized into a cloud before that, of course, and then she met the necessary atmospheric conditions to become a hurricane. The meteorologists have never seen anything quite like this. Doreen, my girlfriend and sometimes fiance, walks to my house with difficulty, and says, upon entering, Your daughter, but she doesnt finish the statement because at that moment the eye passed over us. Doreen looks at me and I look at Doreen and we probably should kiss. We pile into the pickup, the kids in the back, the youngest on Doreen's lap, and we follow the eye for miles, until finally Doreen tells me that being in the eye for so long is like being in the secret place that every woman has. I look to my oldest daughter for confirmation, remembering her awkwardness, and she is too busy looking at the rain. We stop the pickup and let the storm overtake us as we watch the patch of sunshine move into the distance and then disappear over the only hill in the county. Then it starts to rain again. My 14

Ben Wright Fiction Portfolio daughter becomes a Category 3 on day 3. Scientists say this is because of all the heated pools that she is sucking up, but the experts are just grasping at straws. My daughter has moved forty-five miles; and, after each one, we comb through the yards and fields and streams to look for pieces of her. Once, we find a fingernail, and another time we find a 7-carat diamond, but these belong to other people. We decide to set up base camp for a while. One night, Doreen sits on my bed in the motel and looks at me in the mirror as Im gargling and trying to decipher my daughter's last words. After Doreen undresses and I spit out the lukewarm water, we both in, our own way, move on. The hurricane, two days later, swings back around and that night I sit in the long, open hallway of the motel and listen for anything my daughter might be screaming in the wind, but I never hear anything, though the oldest said she hears something. I don't believe her. We track her progress for a while, watching the red line on the computer trace a line through the Midwest, half-hoping that she is trying to spell something out, but there are only swirls, and I am reminded of a spirograph. One night, the youngest asks me where she is. A cloud, I say, or Heaven. The hurricane hunters let me ride in the plane and drop off messages to her, along with scientific instrumentation. I gather letters, report cards, toys, whatever, filling capsule after capsule. Each time I open the hatch, rain flies in, and I imagine that these raindrops are molten parts of her body, a lobe of her liver, perhaps, or a pancreas. My messages to her are like the contents of a time capsule, and in a thousand years, an archaeologist might find them: a girl's shoe, a magazine, a Chinese finger trap, and these archaeologists might think we were very bored, but in reality, I am scared she forgot all of these things once she attained the power and freedom I could never grant her. I drop capsule after capsule until we reach the eye again, and then we turn around, waiting for a message to appear. It never does. Soon, she veers into Lake Superior, like some animal going to die. That's what the scientists 15

Ben Wright Fiction Portfolio say. The hurricane can't sustain itself off of that cold water, but I say that she was always the first person in the pool on Memorial Day, when the water is cold and everyone else is scared. Later, in a motorboat, we scour the lake, finding pike and largemouth bass, cutting them open to look for something, anything of hers, but we only find flotsam floating on the surface: a house; a wig; a bloated body from Peoria; a dog; three wedding rings and a hamster, but nothing nothing nothing of her and nothing of ours.

16

Ben Wright Fiction Portfolio

Dossier And the next time I see that little shit, George continued, Ive got half a mind to wring his neck. Pat put down her fork. George, please. Not at the table. Its true, though. McCaffreys windshield is dinged up, and two blocks over the Rosens is too. Im not saying theyre related incidents, but its very unusual. The child of a drunk is no good. Next door, Paulie Keane was swapping out digging spoons. The tunnel he had started under the Nelsons front porch, heading due north, was three quarters of the way to the property line. His father snored in the front room. Paulie had put the biggest stones in his pockets, and, if he closed his eyes, he could almost hear the freeway. The Nelsons windshield was the fifteenth windshield pitting reported to the police in a week. There were no leads. The editor of the paper was breaking the story on Mondays front page, dropping a human interest piece about a baby born without a tongue. The editor had three reporters covering the case, staking out used car lots and pursuing competing theories. A hawk found washed up on the shore of the river, its stomach filled with pebbles, was taken to the morgue where it rotted slowly in a refrigerator. A topographical map now hung over the blackboard in the polices briefing room, with huge red dots where the pittings had been reported. Someone had solemnly connected the dots, looking for a pattern. The dispatcher said it looked like a cloud. The next night, Tuesday, and nine more pittings later, George Nelson was taken downtown for slapping Paulie Keane, who he found hiding under his car that evening, pockets full. Nelson was released with a warning, and Paulie was interrogated for five hours until his father was sober enough to 17

Ben Wright Fiction Portfolio come pick him up. Paulie confessed to throwing stones into Mr. Kemps pond. The police called the case closed in anticipation of tomorrows newspaper. By Wednesday, 56 more pittings were reported, and the map resembled a bone, or maybe the jagged edge of a mountain. Thursday at 7:15 Leona Kowalski opened her curtains and saw her bay window a fractal, and five dead blackbirds lay in her begonias. Down the street, a screaming match between the Statzes and the Vincenzos was taking place. A whole coop full of chickens was cold that morning, dead on their roosts. A brick was thrown through the elder Keanes beat up Coronet, and another brick was sent to the editor of the newspaper, but was lost in the mail for three weeks. Paulie Keane didnt come to school Friday, or the next Monday. The chief of police noticed his bathwater rippling as he sat silently in the tub, but decided he was just overworked. There was a lull in the pittings Friday, until Marjorie Shoemaker went to put on a necklace and noticed a chip in the middle gemstone. Every single piece of china on display at Sears was discovered to have a pit in it Saturday morning. George Nelson fell asleep that night in his Lancer, shotgun across his waist, until Deputy Laroux knocked on the window around 2 a.m. George fired into the gloom. His wife, embarrassed, later picked the glass out the Deputy Larouxs face with a pair of tweezers. Laroux decided not to press charges and was back at work by Monday. The morgues freezer was full of dead birds. Paulies father asked the Nelsons if they had seen his boy. Sometime during the day, a single crack appeared in the windshield of every car in the courthouse parking lot. Mary Francis Xavier dropped her favorite serving dish on her way from the kitchen to the dining room, but no debris was ever located. At 11 p.m. Paulie Keanes father asked the patrons of Flanagans Pub if they had seen his boy anywhere. Military personnel at nearby Camp Bradley were ordered not to have civilian visitors until 18

Ben Wright Fiction Portfolio the pitting epidemic passed. By Monday afternoon, the total number of pittings in the tri-county area was 573. Most boys were grounded until they gave up names. John Bins, a retired physicist from the Manhattan Project, held a press conference blaming the pittings on high-altitude nuclear tests by the Soviets, which rained down ionized bits of antimatter at night. It would all be over, he said, if we would just go back to the way things were. The Nelsons slept in separate beds that week. No pittings were reported during Tuesdays rain shower. Jane Spitz reported her televisions glowing a bright blue before exploding, but couldnt remember what program she was watching. A fox was found in the park burying a boys shoe, size 8. Paulie Keanes father called Paulie Keanes mother, whom he had not spoken to in a very long time. He wondered aloud where his boy had run off to. Three teenagers were caught hurling rocks off of the railway overpass onto passing cars on Thursday, and were beaten up and arrested. They were from the city, and had skipped class that day to cause a ruckus. More pittings were called in, necessitating a new phone line that wouldnt be installed until sometime the next week. The mayor issued a statement calling for rational thought as he looked at the unsightly pit on the candy bowl on his desk. Sandra Koufax attempted to call the police, but, due to her hysterical state, reported seeing her bathroom mirror bubbling up like a great big boil and exploding to the operator instead. The men of the town eyed each other suspiciously as they drove to work. Paulie Keanes body, missing a size 8 shoe, was discovered in a trashcan in the park. His pockets were full of pebbles. Police are pursued several leads, but temporarily closed the case with the following years Seattle Strangler case. That night, Paulie Keanes father ripped the trashcan away from the shed it was attached to and 19

Ben Wright Fiction Portfolio threw it into the river. He ordered a drink at Flanagans, saying Paulie instead of whiskey. George Nelsons class ring slipped off his finger as he unlocked the door to his house. He cursed as it fell between the boards of his front porch. He noticed the tunnel after he had crawled underneath the porch, ruining his good slacks. He made a mental note to board it up so cats wouldnt get in there during the winter. That night, he dreamed he was on the freeway, trying to flag down a car to help him get to somewhere he couldnt, for the life of him, remember the name of.

20

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- GM Mastery 01Document53 pagesGM Mastery 01Pa DooleyNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Sexual HappinessDocument40 pagesThe Little Book of Sexual Happinesswolf4853100% (2)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- WATERSON, KRISTAL BENTLEY 71775151-Autopsy-Report PDFDocument4 pagesWATERSON, KRISTAL BENTLEY 71775151-Autopsy-Report PDFSarah Beth Breck100% (1)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Developmental Biology QuestionsDocument10 pagesDevelopmental Biology QuestionsSurajit Bhattacharjee100% (1)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Language of Medicine 10th Edition Chabner Test BankDocument25 pagesLanguage of Medicine 10th Edition Chabner Test BankNathanToddkprjq100% (62)

- Chapter 4 Tissue - The Living FabricDocument23 pagesChapter 4 Tissue - The Living FabricMariaNo ratings yet

- Reams-RBTI Alphabetical Reference Manual by Stanley & Gertrude Gardner Reams Seminars 1975-1977Document144 pagesReams-RBTI Alphabetical Reference Manual by Stanley & Gertrude Gardner Reams Seminars 1975-1977Steve DiverNo ratings yet

- Glossary English - Romanian Medical TermsDocument4 pagesGlossary English - Romanian Medical TermsGhita Geanina0% (1)

- Cs Breast EngorgementDocument14 pagesCs Breast Engorgementamit85% (13)

- SONAC-Aqua Feed MarketDocument4 pagesSONAC-Aqua Feed MarketDiel MichNo ratings yet

- Variability and Accuracy of Sahlis Method InEstimation of Haemoglobin ConcentrationDocument8 pagesVariability and Accuracy of Sahlis Method InEstimation of Haemoglobin Concentrationastrii 08No ratings yet

- Background KarunkelDocument2 pagesBackground KarunkeldatascribdyesNo ratings yet

- Nipah Virus Infection: ImportanceDocument9 pagesNipah Virus Infection: ImportanceSivaNo ratings yet

- Studi Deskriptif Mengenai Resiliensi Pada ODHA Di Komunitas KDS Puzzle Club BandungDocument7 pagesStudi Deskriptif Mengenai Resiliensi Pada ODHA Di Komunitas KDS Puzzle Club BandungArif GustyawanNo ratings yet

- Charnley Ankle ArthrodesisDocument12 pagesCharnley Ankle Arthrodesisdr_s_ganeshNo ratings yet

- Petri DishDocument7 pagesPetri DishMizzannul HalimNo ratings yet

- The Urinary SystemDocument2 pagesThe Urinary SystemArl PasolNo ratings yet

- The Use of Intra Repiderma in The Healing of Dehorning Disbudding Wounds 16.01.2014Document14 pagesThe Use of Intra Repiderma in The Healing of Dehorning Disbudding Wounds 16.01.2014IntracareNo ratings yet

- Pasteurization of Mother's Own Milk Reduces Fat Absorption and Growth in Preterm InfantsDocument5 pagesPasteurization of Mother's Own Milk Reduces Fat Absorption and Growth in Preterm InfantsDianne Faye ManabatNo ratings yet

- I Lipo New Patient PacketDocument8 pagesI Lipo New Patient PacketLuis A Gil PantojaNo ratings yet

- Nutrition: Important ConceptsDocument12 pagesNutrition: Important ConceptshafizaqaiNo ratings yet

- Nose Fracture and Deviated SeptumDocument17 pagesNose Fracture and Deviated Septummimi2188No ratings yet

- Annatomy Notes For Bpe StudDocument14 pagesAnnatomy Notes For Bpe StudYoga KalyanamNo ratings yet

- Properties and Applications of Palygorskite-Sepiolite ClaysDocument11 pagesProperties and Applications of Palygorskite-Sepiolite Clayssri wulandariNo ratings yet

- Nur112: Anatomy and Physiology ISU Echague - College of NursingDocument14 pagesNur112: Anatomy and Physiology ISU Echague - College of NursingWai KikiNo ratings yet

- D 5 LRDocument2 pagesD 5 LRDianelie BacenaNo ratings yet

- Import Requirements (NEW)Document15 pagesImport Requirements (NEW)Thiago NunesNo ratings yet

- EsquistocitosDocument10 pagesEsquistocitoswillmedNo ratings yet

- A Case of Subcorneal Pustular Dermatosis Successfully Treated With AcitretinDocument3 pagesA Case of Subcorneal Pustular Dermatosis Successfully Treated With Acitretindr_RMNo ratings yet

- Key Points in Obstetrics and Gynecologic Nursing A: Ssessment Formulas !Document6 pagesKey Points in Obstetrics and Gynecologic Nursing A: Ssessment Formulas !June DumdumayaNo ratings yet