Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Tallent No Ones A Mystery W Comments

Uploaded by

totipotent3395Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Tallent No Ones A Mystery W Comments

Uploaded by

totipotent3395Copyright:

Available Formats

1st person narrator, 18-year-old female, unnamed, past tense.

Birthday triggers the action--gift of a diary.

Conflict expressed in action.

Other characters: Jack, narrator's older lover; his wife.

Begins a pattern of little things not quite right in the scene. See also the manure below. Also helps fix diary in reader's mind for later. Also seems vaguely symbolic, of what I don't know.

Dialogue technique: notanswering by the use of questions.

Beginning of For my eighteenth birthday Jack gave me a five-year diary with a latch and a wife theme: wife causes little key, light as a dime. I was sitting beside him scratching at the lock, interference which didn't seem to want to work, when he thought he saw his wife's that drives Cadillac in the distance, coming toward us. He pushed me down onto the the scene. dirty floor of the pickup and kept one hand on my head while I inhaled the musk of his cigarettes in the dashboard ashtray and sang along with Rosanne Cash on the tape deck. We'd been drinking tequila and the bottle was between his legs, resting up against his crotch, where the seam of his Levi's was They've been bleached linen-white, though the Levi's were nearly new. I don't know why drinking--comedy his Levi's always bleached like that, along the seams and at the knees. In a here. curve of cloth his zipper glinted, gold. "It's her," he said. "She keeps the lights on in the daytime. I can't think of a single habit in a woman that irritates me more than that." When he saw that I was going to stay still he took his hand from my head and ran it through his Eroticism in own dark hair. her safer, safer "Why does she?" I said. observations "She thinks it's safer. Why does she need to be safer? She's driving about his exactly fifty-five miles an hour. She believes in those signs: crotch.

No One's a Mystery by Elizabeth Tallent

The conflict of the story is between the narrator and Jack; she wants to believe in a romantic future for them and he doesn't believe in it. There are basically two scenes each of which has its own interference, or secondary conflict, something that drives the dramatic interest of the scene and also expresses the main conflict. The first scene uses 10 Short Fiction Jack's wife driving by and the second scene uses the diary.

Run of parallel constructions: she'll see, she'll know, she'll think--the last is a dialogue interruption. Wife 55 mph; Jack 80 mph. Characterization by contrast.

Manure--another things not quite right in the scene. Dialogue technique of not answering by repeating the words of the previous speaker. A triplet: little kids, little kids, kid.

Five repetitions of "know" make the transition to the diary theme.

No backfill in `Speed Monitored by Aircraft.' It doesn't matter that you can look up story, only and see that the sky is empty." this reference "She'll see your lips move, Jack. She'll know you're talking to to their 2 years someone." together. "She'll think I'm singing along with the radio." He didn't lift his hand, just raised the fingers in salute while the pressure of his palm steadied the wheel, and I heard the Cadillac honk twice, Rosanne musically; he was driving easily eighty miles an hour. I studied his boots. The Cash elk heads stitched into the leather were bearded with frayed thread, the toes repeated were scuffed, and there was a compact wedge of muddy manure between twice. the heel and the solethe same boots he'd been wearing for the two years I'd known him. On the tape deck Rosanne Cash sang, "Nobody's into me, no Dial. one's a mystery." "Do you think she's getting famous because of who her daddy is or for technique of not herself?" Jack said. "There are about a hundred pop tops on the floor, did you know that? answering by Some little kid could cut a bare foot on one of these, Jack." indirection. "No little kids get into this truck except for you." "How come you let it get so dirty?" " `How come,' he mocked. "You even sound like a kid. You can get back into the seat now, if you want. She's not going to look over her End of wife shoulder and see you." theme. Structural transition. "How do you know?" "I just know," he said. "Like I know I'm going to get meat loaf for supper. It's in the air. Like I know what you'll be writing in that diary." "What will I be writing?" I knelt on my side of the seat and craned Start of around to look at the butterfly of dust printed on my jeans. Outside the diary theme. window Wyoming was dazzling in the heat. The wheat was fawn and yellow and parted smoothly by the thin dirt road. I could smell the water in the irrigation ditches hidden in the wheat. "Tonight you'll write, ' I love Jack. This is my birthday present from him. I can't imagine anybody loving anybody more than I love Jack." "I can't." "In a year you'll write, `I wonder what I ever really saw in Jack. I wonder why I spent so many days just riding around in his pickup. It'.s true he taught me something about sex. It's true there wasn't ever much else to do in Cheyenne.' " "I won't write that." "In two years you'll write, `I wonder what that old guy's name was, the one with the curly hair and the filthy dirty pickup truck and time on his hands.' "

Story title repeated in text.

Here we have the first of two blocks of text structured around two sets of answering parallel structures hypothesizing future diary entries; the diary entries embody the conflict between the narrator and Jack, their contrary dreams for the future.

Time: She's 18, they have been together 2 years, the blocks of parallel constructions send the story Short Fiction 11 into conflicting constructions of the future, 3 years hence.

Second block of parallels.

Anadiplosis

"I won't write that." "No?" "Tonight I'll write, `I love Jack. This is my birthday present from him. I can't imagine anybody loving anybody more than I love Jack.' " "No, you can't," he said. "You can't imagine it." "In a year I'll write, `Jack should be home any minute now. The table's setmy grandmother's linen and her old silver and the yellow candles left over from the weddingbut I don't know if I can wait until after the trout a la Navarra to make love to him.' " "It must have been a fast divorce." "In two years I'll write, `Jack should be home by now. Little Jack is hungry for his supper. He said his first word today besides "Mama" and "Papa." He said "kaka." ' " Jack laughed. "He was probably trying to finger-paint with kaka on the bathroom wall when you heard him say it." kaka, kaka "In three years I'll write, `My nipples are a little sore from nursing Eliza Rosamund.' "Rosamund. Every little girl should have a middle name she hates." " `Her breath smells like vanilla and her eyes are just Jack's color of blue.' "That's nice." Jack said. "So, which one do you like?" "I like yours," he said. "But I believe mine." "It doesn't matter. I believe mine." "Not in your heart of hearts, you don't." "You're wrong." "I'm not wrong," he said. "And her breath would smell like your milk, and it's kind of a bittersweet smell, if you want to know the truth." In this last passage, an instance of epanalepsis brackets a delicate and poetic run of repetitions, all in dialogue, all terse, all in disagreement, except for " heart of hearts."

I won't write that, I won't write that.

Epanalepsis

The story is so formally structured on parallels and repetitions (rhymes) that it can't but remind one of Viktor Shklovsky's theories about the use of parallel structure and repetition as devices of delay, delay being one of the essentail functions of literary language. See his discussion of parallelism, repetition and step-by-step consruction in "Plot Construction and Style" in his book Theory of Prose (pp24-30). Comments by Douglas Glover dg@douglasglover.net

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- How It Feels To Be Colored Me, by Zora Neale HurstonDocument3 pagesHow It Feels To Be Colored Me, by Zora Neale HurstonIuliana Tomozei67% (9)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Orthodox Prayer Life PDFDocument290 pagesOrthodox Prayer Life PDFHanna Papp100% (1)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Pride and Prejudice SUMMARYDocument10 pagesPride and Prejudice SUMMARYfilzansari100% (2)

- AB-036090-001 Joints For Cement Lined PipeDocument1 pageAB-036090-001 Joints For Cement Lined Pipenarutothunderjet216100% (1)

- GRE Vocabulary List 2Document33 pagesGRE Vocabulary List 2abhishek_k09No ratings yet

- English Blackwork FillworkDocument17 pagesEnglish Blackwork FillworkRanaWardeh100% (4)

- Baldwin James - If Black English Isnt A LanguageDocument2 pagesBaldwin James - If Black English Isnt A Languagetotipotent3395No ratings yet

- Baraka Amiri - The Revolutionary TheatreDocument3 pagesBaraka Amiri - The Revolutionary Theatretotipotent3395No ratings yet

- The Rime of The Ancient Mariner PDFDocument3 pagesThe Rime of The Ancient Mariner PDFGauravi SawantNo ratings yet

- RBC and WBC Pipette GuideDocument11 pagesRBC and WBC Pipette GuideShreyash KumarNo ratings yet

- 10 Days of Prayer 2020Document41 pages10 Days of Prayer 2020Cargo ReeNo ratings yet

- Holy Spirit in Acts and Early ChurchDocument21 pagesHoly Spirit in Acts and Early ChurchMollyn NhiraNo ratings yet

- SAT May 2011 CR+Writing OnlyDocument43 pagesSAT May 2011 CR+Writing Onlytotipotent3395No ratings yet

- NVC Flexographic EguideDocument21 pagesNVC Flexographic EguideBernard Andre Palacios Gomez100% (1)

- Past Simple Regular and Irregular VerbsDocument13 pagesPast Simple Regular and Irregular VerbsMarlon ChiliquingaNo ratings yet

- SAT 2008 JAN SAT CR+Writing Only, No AnswersDocument28 pagesSAT 2008 JAN SAT CR+Writing Only, No Answerstotipotent3395No ratings yet

- March 2010 SC VocabDocument5 pagesMarch 2010 SC Vocabtotipotent3395No ratings yet

- The Classic of Xiao - Zeng Zi's Treatise on Filial PietyDocument24 pagesThe Classic of Xiao - Zeng Zi's Treatise on Filial Pietytotipotent3395No ratings yet

- January Test DefinitionsDocument17 pagesJanuary Test Definitionstotipotent3395No ratings yet

- The Lady or The Tiger Guided ReadingDocument10 pagesThe Lady or The Tiger Guided ReadingbongarciaNo ratings yet

- Two Ways of Seeing A RiverDocument2 pagesTwo Ways of Seeing A RiverFrank Hobbs100% (1)

- Woody Allen's 1979 Speech Warns of Hopelessness and ExtinctionDocument2 pagesWoody Allen's 1979 Speech Warns of Hopelessness and Extinctiontotipotent3395No ratings yet

- Discourses Asian-American Journal 1Document44 pagesDiscourses Asian-American Journal 1totipotent3395No ratings yet

- The Milk-Maid's Dream: MORAL: Building Castles in Air Will Not StandDocument1 pageThe Milk-Maid's Dream: MORAL: Building Castles in Air Will Not StandDheepiga SRNo ratings yet

- Submitted by Saqib Ali Word MeaningDocument3 pagesSubmitted by Saqib Ali Word MeaningSaqib AliNo ratings yet

- First Quarter ExaminationDocument4 pagesFirst Quarter ExaminationEDSEL ALAPAGNo ratings yet

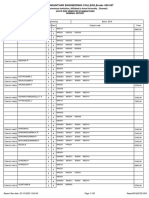

- ERODE SENGUNTHAR ENGINEERING COLLEGE Nominal ReportDocument133 pagesERODE SENGUNTHAR ENGINEERING COLLEGE Nominal ReportSridhar JayaramanNo ratings yet

- The Occult: by Hugh ReaumeDocument12 pagesThe Occult: by Hugh ReaumeBot PsalmernaNo ratings yet

- Malla DynastyDocument7 pagesMalla DynastyLastMinute ExamNo ratings yet

- Teaching - Trailers - PlanDocument11 pagesTeaching - Trailers - PlandinaradinaraNo ratings yet

- Supersonic 2018 CatalogDocument107 pagesSupersonic 2018 CatalogSupersonic Inc.No ratings yet

- Coyote Places The Stars Lesson PlanDocument6 pagesCoyote Places The Stars Lesson Planapi-306779366100% (1)

- In Jesus Name worship songDocument2 pagesIn Jesus Name worship songJuan KarloNo ratings yet

- A Woman SpeaksDocument6 pagesA Woman SpeaksGérard OrigliassoNo ratings yet

- Guinobatan Elementary SchoolDocument3 pagesGuinobatan Elementary SchoolPhoebe LanoNo ratings yet

- Life Is Real! Life Is Earnest! and The Grave Is Not Its GoalDocument2 pagesLife Is Real! Life Is Earnest! and The Grave Is Not Its GoalJanna Nicole Torres RodriguezNo ratings yet

- D&D5e - Party Tracker PDFDocument1 pageD&D5e - Party Tracker PDFMike van der ZijdenNo ratings yet

- Young - The Cinema Dreams Its Rivals. From Radio To The Internet (2006)Document350 pagesYoung - The Cinema Dreams Its Rivals. From Radio To The Internet (2006)Yanoad FlórezNo ratings yet

- Rajput Painting Vol.02Document330 pagesRajput Painting Vol.02Amlan singhaNo ratings yet

- MICHELMAN - French and British Colonial Language PoliciesDocument11 pagesMICHELMAN - French and British Colonial Language PoliciesAbel DjassiNo ratings yet

- The Execution of DR - Jose RizalDocument4 pagesThe Execution of DR - Jose RizalUserNo ratings yet

- AL - 2.1 - Brief IntroductionDocument18 pagesAL - 2.1 - Brief IntroductionAgha Khan DurraniNo ratings yet

- Do You Know Quran Verses About Prayer (Salah & Namaz) PDFDocument1 pageDo You Know Quran Verses About Prayer (Salah & Namaz) PDFnadeemNo ratings yet