Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Skin Put

Skin Put

Uploaded by

neharacharla3491Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Skin Put

Skin Put

Uploaded by

neharacharla3491Copyright:

Available Formats

CHINMAYAINSTITUTEOFTECHNOLOGY KANNUR SEMINARREPORT On SKINPUT Presentedby DEEPAKVADAKKEVEETTIL MCAFOURTHSEMESTER SCHOOLOFCOMPUTERSCIENCE AND INFORMATIONTECHNOLOGY

CHINMAYAINSTITUTEOFTECHNOLOGY KANNUR SCHOOLOFCOMPUTERSCIENCE AND INFORMATIONTECHNO DECLARATION IDEEPAKVADAKKEVEETTIL,FOURTHSemesterMCA,studentofChinmayaInstituteof Technology, hattheSeminarReportentitledSKINPUTistheoriginalwork carriedoutbymeunderthesup MPtowardspartialfulfillmentofthe requirementofMCADegree. SignatureoftheStudent Kannur: Date:

CHINMAYAINSTITUTEOFTECHNOLOGY KANNUR SCHOOLOFCOMPUTERSCIENCE AND INFORMATIONTECHNO FICATE ThisistocertifythattheSeminarReporttitledSKINPUTwaspreparedandpresentedbyDEEPA choolofComputerScienceandInformationTechnology,Chinmaya InstituteofTechnologyinpa mentoftherequirementasasubjectundertheUniversityof KannurduringtheFOURTHsemest FacultyinCharge Kannur Date:

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First of all, I express my sincere thanks to Principal Dr.K.K.Falgunanfo vinglotofencouragement. IamthankfultoallfacultymembersinMCAdepartment tations. Atlast,butnottheleastIwouldliketoexpressmythankstoomnipot ethankstomyfriends,whohaveparticipatedin theseminarandencouragedmemuch.

ABSTRACT We present Skinput, a technology that appropriates the human body for a ansmission,allowingtheskintobeusedasaninputsurface.Inparticular,weresolvethel earmandhandbyanalyzingmechanicalvibrationsthatpropagatethroughthe body.Wecollec ovelarrayofsensorswornasanarmband.Thisapproach providesanalwaysavailable,natura dyfingerinputsystem.Weassessthe capabilities,accuracyandlimitationsofourtechniqu wentyparticipantuser study.Tofurtherillustratetheutilityofourapproach,weconclude fconcept applicationswedeveloped. AuthorKeywords Bioacoustics, finger input, bu stures, onbody interaction, projected displays, audio interfaces.

CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 1 2 4 4 5 7 7 9 11 13 15 18 20 21 2. RELATED WORK 3. SKINPUT 4. BIO-ACOUSTIC 5. SENSING 6. ARMBAND PROTOTYPE 7. PR OCESSING 8. EXPERIMENT 9. DESIGN AND SETUP 10. RESULTS 11. SUPPLEMENTALEXPERIMENT S 12. EXAMPLEINTERFACESANDINTERACTIONS 13. CONLUSION 14. REFERENCE

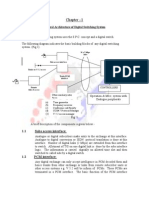

INTRODUCTION Deviceswithsignificantcomputationalpowerandcapabilitiescannowbeeasily urbodies.However,theirsmallsizetypicallyleadstolimitedinteractionspaceandconsequ estheirusabilityandfunctionality.Sincewecannotsimplymakebuttonsandscreenslarger rimarybenefitofsmallsize,weconsideralternativeapproachesthatenhance interactionsw esystems. One option is to opportunistically appropriate surface area from ironment for interactivepurposes.Forexample,describesatechniquethatallowsasmall rn tablesonwhichitrestsintoagesturalfingerinputcanvas.However,tablesarenotalw mobile context, users are unlikely to want to carry appropriated surfaces em. However,thereisonesurfacethathasbeenpreviousoverlookedasaninputcanvas,and ravelwithus:ourskin.Appropriatingthehumanbodyasaninputdeviceis appealingnoton osquaremetersofexternalsurfacearea,butalso becausemuchofitiseasilyaccessibleb roprioceptionoursenseof howourbodyisconfiguredinthreedimensionalspaceallows r bodiesinaneyesfreemanner.Forexample,wecanreadilyflickeachofourfingers,touc ndstogetherwithoutvisualassistance.Fewexternalinputdevicescan claimthisaccurate, racteristicandprovidesuchalargeinteractionarea. In this paper, we present o input a method that allows the body to be appropriatedforfingerinput ve,wearablebioacousticsensor. Thecontributionsofthispaperare: 1) We describe t a novel, wearable sensor for bioacoustic signal acquisition (Figure1). 2) We nanalysisapproachthatenablesoursystemtoresolvethelocationoffinger tapsonthebo tnessandlimitationsofthissystemthroughauserstudy. 4) We explore the broader ustic input through prototype applications and additionalexperimentation. 1

Awearable,bioacousticsensingarraybuiltintoanarmband.Sensingelementsdetectvibrati dthroughthebody.Thetwosensorpackagesshownaboveeachcontainfive,specially weighte zofilms,responsivetoaparticularfrequencyrange. RELATEDWORK AlwaysAvailableInput kinputistoprovideanalwaysavailablemobileinputsystemthatis, aninputsystemthat ckupadevice.Anumberofalternative approacheshavebeenproposedthatoperateinthis ncomputervisionare popular.These,however,arecomputationallyexpensiveanderrorprone ios.Speech inputisalogicalchoiceforalwaysavailableinput,butislimitedinitsprec cousticenvironments,andsuffersfromprivacyandscalabilityissuesinsharedenvironments. aches havetakenthe form ofwearablecomputing.This typicallyinvolves a physicalinp rmconsideredtobepartofonesclothing.Forexample,glove based input systems all n most of their natural hand movements, but are cumbersome,uncomfortable,a vetotactilesensation.PostandOrthpresentasmart fabricsystemthatembedssensorsa ttakingthisapproachtoalways availableinputnecessitatesembeddingtechnologyinallcl ldbeprohibitively complexandexpensive.TheSixthSenseprojectproposesamobile,alwaysa t/output capabilitybycombiningprojectedinformationwithacolormarkerbasedvisiontrac isapproachisfeasible,butsuffersfromseriousocclusionandaccuracylimitations.Forexa ing whether, e.g., a finger has tapped a button, or is merely hoverin is extraordinarilydifficult.Inthepresentwork,webrieflyexplorethecombinationof nbodyprojection. 2

BioSensing Skinputleveragesthenaturalacousticconductionpropertiesofthehumanbodyt ystem,andisthusrelatedtopreviousworkintheuseofbiologicalsignalsforcomputer in llyusedfordiagnosticmedicine,suchasheartrateandskinresistance,have beenappropri ersemotionalstate.Thesefeaturesaregenerallysubconsciously drivenandcannotbecontr ientprecisionfordirectinput.Similarly,brainsensing technologies such as electro graphy (EEG) and functional near infrared spectroscopy (fNIR)havebeenusedby rstoassesscognitiveandemotionalstate;thisworkalso primarilylookedatinvoluntarys ,brainsignalshavebeenharnessedasadirect input for use by paralyzed patient rain computer interfaces (BCIs) still lack the bandwidth required for eve puting tasks, and require levels of focus, training, and concentrationthat tiblewithtypicalcomputerinteraction.Therehasbeenlesswork relatingtotheintersecti dbiologicalsignals.Researchershaveharnessedthe electrical signals generated by ctivation during normal hand movement through electromyography. At present, ho , this approach typically requires expensive amplification systemsandtheapplication ivegelforeffectivesignalacquisition,whichwouldlimitthe acceptabilityofthisapproa heinputtechnologymostrelatedtoourownisthatofAmentoetal,whoplacedcontact micr ingermovement.However,thisworkwasneverformally evaluated,asisconstrainedtofinger heHambonesystememploysasimilar setup, and through an HMM, yields classifica cies around 90% for four gestures. Performanceoffalsepositiverejectionremains thsystemsatpresent.Moreover,both techniquesrequiredtheplacementofsensorsnearthe ,increasingthedegreeof invasivenessandvisibility. Finally, bone conduction micr nd headphones now common consumer technologiesrepresentanadditionalbiosen tisrelevanttothepresentwork. Theseleveragethefactthatsoundfrequenciesrelevantt ewellthrough bone. Bone conduction microphones are typically worn near the re they can sense vibrationspropagatingfromthemouthandlarynxduringspeech.Bone hones sendsoundthroughthebonesoftheskullandjawdirectlytotheinnerear,bypassing roughtheairandouterear,leavinganunobstructedpathforenvironmentalsounds. 3

AcousticInput Ourapproachisalsoinspiredbysystemsthatleverageacoustictransmission rfaces.Paradisoetal.[21]measuredthearrivaltimeofasoundatmultiplesensorstoloca .Ishiietal.[12]useasimilarapproachtolocalizeaballhittingatable,for computer e.Bothofthesesystemsuseacoustictimeofflightfor localization,whichweexplored,bu tlyrobustonthehumanbody,leadingto thefingerprintingapproachdescribedinthispape erangeofsensingmodalitiesforalwaysavailableinputsystems,weintroduce Skinput,ano hatallowstheskintobeusedasafingerinputsurface.Inour prototypesystem,wechoos ctiveareatoappropriateasit provides considerable surface area for interaction ng a contiguous and flat area for projection. Furthermore, the forearm a contain a complex assemblage of bones that increasesacousticdistinctivenessof tlocations.Tocapturethisacousticinformation,we developedawearablearmbandthatisn yremovable(Figures1and5). Inthissection,wediscussthemechanicalphenomenathatena ific focusonthemechanicalpropertiesofthearm.ThenwewilldescribetheSkinputsensor chniques we use to segment, analyze, and classify bioacoustic signals. F ransversewavepropagation:Fingerimpactsdisplacetheskin,creatingtransversewaves(ripp nsorisactivatedasthewavepassesunderneathit. BIOACOUSTICS Whenafingertapsthesk sofacousticenergyareproduced.Some energyisradiatedintotheairassoundwaves;this inputsystem. Amongtheacousticenergytransmittedthroughthearm,themostreadilyvisibl aves,createdbythedisplacementoftheskinfromafingerimpact(Figure2).Whenshotwith pearasripples,whichpropagateoutwardfromthepointofcontact.The amplitudeoftheser oththetappingforceandtothevolumeandcompliance ofsofttissuesundertheimpactarea egionsofthearmcreateshigher amplitudetransversewavesthantappingonboneyareas,whi mpliance. In addition to the energy that propagates on the surface of me energy is 4

transmittedinward,towardtheskeleton(Figure3).Theselongitudinal(compressive)wavestr ghthesofttissuesofthearm,excitingthebone,whichismuchlessdeformablethenthesof hanicalexcitationbyrotatingandtranslatingasarigidbody.This excitation vibrates surrounding the entire length of the bone, resulting in new longitudina opagateoutwardtotheskin. Wehighlightthesetwoseparateformsofconductiontransverse lyalong the arm surface, and longitudinal waves moving into and out of ugh soft tissues becausethesemechanismscarryenergyatdifferentfrequenciesandover nces. Roughlyspeaking,higherfrequenciespropagatemorereadilythroughbonethanthrough ndboneconductioncarriesenergyoverlargerdistancesthansofttissueconduction.Whilewe odelthespecificmechanismsofconduction,ordependonthesemechanismsforour analysis, ssofourtechniquedependsonthecomplexacousticpatternsthat resultfrommixturesofth larly,wealsobelievethatjoints playanimportantroleinmakingtappedlocations acoust . Bones are held together by ligaments, and joints often include additi gicalstructuressuchasfluidcavities.Thismakesjointsbehaveasacousticfilters.Insom plydampenacoustics;inothercases,thesewillselectivelyattenuatespecific frequencies, ationspecificacousticsignatures.

SENSING Tocapturetherichvarietyofacousticinformationdescribedintheprevioussectio many sensing technologies, including bone conduction microphones, conventional

microphonescoupledwithstethoscopes,piezocontactmicrophones,andaccelerometers.However e transducers were engineered for very different applications than measurin ustics transmittedthroughthehumanbody.Assuch,wefoundthemtobelackinginseverals ost,mostmechanicalsensorsareengineeredtoproviderelativelyflatresponsecurves over nciesthatisrelevanttooursignal.Thisisadesirablepropertyformost applicationswhe ationofaninputsignaluncoloredbythepropertiesofthe transducerisdesired.However ffrequenciesisconductedthroughthe arminresponsetotapinput,aflatresponsecurvel vantfrequenciesand thustoahighsignaltonoiseratio. Whileboneconductionmicrophone hoiceforSkinput,thesedevices aretypicallyengineeredforcapturinghumanvoice,andfil wtherangeofhuman speech(whoselowestfrequencyisaround85Hz).Thusmostsensorsinth iallysensitivetolowerfrequencysignals(e.g.,25Hz),whichwefoundinourempiricalpilo haracterizingfingertaps.

Figure4.Responsecurve(relativesensitivty)ofthesensingelementthatresonatesat78Hz ponsecurveforoneofoursensors,tunedtoaresonantfrequencyof78Hz. Thecurveshowsa sonantfrequency.Additionally,the cantileveredsensorswerenaturallyinsensitivetoforce ltotheskin(e.g.,shearingmotions causedbystretching).Thus,theskinstretchinduced ts(e.g.,reachingfor a doorknob) tends to be attenuated. However, the sens hly responsive to motion perpendiculartotheskinplaneperfectforcapturingtrans Figure2)and longitudinal waves emanating from interior structures. Finally, sor design is relatively inexpensiveandcanbemanufacturedinaverysmallformfact tableforinclusion infuturemobiledevices. 6

ARMBANDPROTOTYPE Ourfinalprototype,showninFigures1and5,featurestwoarraysoffive orporatedintoanarmbandformfactor.Thedecisiontohavetwosensorpackageswasmotivated nput.Inparticular,whenplacedontheupperarm(abovetheelbow), wehopedtocollectaco efleshybicepareainadditiontothefirmerareaon theundersideofthearm,withbetter s,themainbonethatruns fromshouldertoelbow.Whenthesensorwasplacedbelowtheelbo aslocatedneartheRadius,thebonethatrunsfromthelateralsideoftheelbowtothethum rtheUlna,whichrunsparalleltothisonthemedialsideofthearm closesttothebody. tlydifferentacousticcoverageandinformation, helpfulindisambiguatinginputlocation. tdatacollection,weselectedadifferentsetofresonantfrequenciesforeach sensor pac We tuned the upper sensor package to be more sensitive to lower fre stheseweremoreprevalentinfleshierareas.Conversely,wetunedthelower sensorarrayt equencies,inordertobettercapturesignalstransmitted though(denser)bones.

PROCESSING In our prototype system, we employ a Mackie Onyx 1200F audio to digitally capture data from the ten sensors. This was connected vi to a conventional desktop computer, where a thin client written in C int h the device using the Audio Stream Input/Output(ASIO)protocol. 7

Eachchannelwassampledat5.5kHz,asamplingratethatwouldbeconsideredtoolowfor spe audio, but was able to represent the relevant spectrum of frequencies transmit hearm.Thisreducedsampleratemakesourtechniquereadilyportableto embeddedprocessors mega168processoremployedbytheArduinoplatform cansampleanalogreadingsat77kHzwith ndcouldthereforeprovidethefull samplingpowerrequiredforSkinput. Datawas then se overa local sockettoourprimaryapplication, writteninJava.Thisprogramperformed rst,itprovidedalivevisualizationof the data from our ten sensors, which dentifying acoustic features. Second, it segmentedinputsfromthedatastreaminto nstances(taps).Third,itclassifiedthese inputinstances. Theaudiostreamwassegmented ltapsusinganabsoluteexponentialaverage ofalltenchannels.Whenanintensitythreshol gramrecordedthetimestamp asapotentialstartofatap.Iftheintensitydidnotfallbel ng thresholdbetween100msand700msaftertheonsetcrossing,theeventwasdiscarded.If redetectedthatsatisfiedthesecriteria,theacousticdatainthatperiod(plusa60ms buf ideredaninputevent(Figure6,verticalgreenregions).Although simple, this heuristi e highly robust, mainly due to the extreme noise suppression providedbyour ch.Afteraninputhasbeensegmented,thewaveformsareanalyzed. Thehighlydiscretenatur acts)meantacousticsignalswerenotparticularly expressiveovertime.Signalssimplydimi sityovertime.Thus,featuresarecomputed overtheentireinputwindowanddonotcapturea 8

Weemployabruteforcemachinelearningapproach,computing186featuresintotal,many of natorially.Forgrossinformation,weincludetheaverageamplitude, standarddeviationand te)energyofthewaveformsineachchannel(30features).From these,wecalculateallaver tweenchannelpairs(45features).Wealsoinclude anaverageoftheseratios.Wecalculate nnels,althoughonlythe lowertenvaluesareused,yielding100features.Thesearenormali itudeFFT valuefoundonanychannel.Wealsoincludethecenterofmassofthepowerspectr ngeforeachchannel,aroughestimationofthefundamentalfrequencyofthe signaldisplaci quentfeatureselectionestablishedtheallpairsamplituderatios andcertainbandsofthe tivefeatures. These 186 features are passed to a Support Vector Machine sifier. A full description ofSVMs is beyondthe scopeof this paper.Oursoftwa ntation provided in the Weka machine learning toolkit. It should be note r, that other, more sophisticatedclassificationtechniquesandfeaturescouldbeempl heresultspresented inthispapershouldbeconsideredabaseline. BeforetheSVMcanclas tmustfirstbetrainedtotheuserandthe sensorposition.Thisstagerequiresthecollect achinputlocationof interest.WhenusingSkinputtorecognizeliveinput,thesame186aco uted ontheflyforeachsegmentedinput.ThesearefedintothetrainedSVMforclassifica oftwareonceaninputisclassified,aneventassociatedwiththatlocationis instantiate uresboundtothateventarefired.Ascanbeseeninourvideo,we readilyachieveinteract rticipants Toevaluatetheperformanceofoursystem,werecruited13participants(7female eattlearea.Theseparticipantsrepresentedadiversecrosssectionofpotentialagesand bo edfrom20to56(mean38.3),andcomputedbodymassindexes(BMIs) rangedfrom20.5(normal entalConditions Weselectedthreeinputgroupingsfromthemultitudeofpossiblelocationc

test.Webelievethatthesegroupings,illustratedinFigure7,areofparticularinterestwi facedesign,andatthesametime,pushthelimitsofoursensingcapability.Fromthesethre vedifferentexperimentalconditions,describedbelow. Fingers(FiveLocations) Onesetof tedhadparticipantstappingonthetipsofeachoftheirfivefingers (Figure 6, Finge er interesting affordances that make them compelling to appropriateforinput. ,theyprovideclearlydiscreteinteractionpoints,whichareeven alreadywellnamed(e.g., itiontofivefingertips,thereare14knuckles(five major,nineminor),which,takentoge ilyidentifiableinputlocationsonthe fingersalone.Second,wehaveexceptionalfingerto sdemonstratedwhenwe countbytappingonourfingers.Finally,thefingersarelinearlyor allyuseful forinterfaceslikenumberentry,magnitudecontrol(e.g.,volume),andmenusel etime,fingersareamongthemostuniformappendagesonthebody,withallbut the thumb keletal and muscular structure. This drastically reduces acoustic variationan ifferentiatingamongthemdifficult.Additionally,acousticinformationmust crossasmanya randwrist)jointstoreachtheforearm,whichfurtherdampenssignals. Forthisexperiment ecidedtoplacethesensorarraysontheforearm,just below the elbow. Despite thes pilot experiments showed measureable acoustic differencesamongfingers,whichwe sprimarilyrelatedtofingerlengthandthickness, interactions with the complex st the wrist bones, and variations in the acoustic transmissionpropertiesofthe ndingfromthefingerstotheforearm. WholeArm(FiveLocations)

Figure7:Thethreeinputlocationsetsevaluatedinthestudy. Anothergesturesetinvestig tlocationsontheforearmandhand:arm,wrist, 10

palm,thumbandmiddle finger(Figure7,Whole Arm).Weselectedthese locations fortw st,theyaredistinctandnamedpartsofthebody(e.g.,wrist).Thisallowed participants these locations without training or markings. Additionally, these locationspr eacousticallydistinctduringpiloting,withthelargespatialspreadofinput points off variation. We used these locations in three different conditions. One c acedthesensorabovetheelbow,whileanotherplaceditbelow.Thiswasincorporated into o measure the accuracy loss across this significant articulation point (t ).Additionally,participantsrepeatedthelowerplacementconditioninaneyesfreecontext: s were told to close their eyes and face forward, both for training This conditionwasincludedtogaugehowwelluserscouldtargetonbodyinputlocations .,driving). Forearm(TenLocations) Inanefforttoassesstheupperboundofourapproach rfifthand finalexperimentalconditionusedtenlocationsonjusttheforearm(Figure6, eryhighdensityofinputlocations(unlikethewholearmcondition),butitalsoreliedon rm)withahighdegreeofphysicaluniformity(unlike,e.g.,thehand).We expected that uld make acoustic sensing difficult. Moreover, this location was compelling rgeandflatsurfacearea,aswellasitsimmediateaccessibility,bothvisually and for multaneously, this makes for an ideal projection surface for dynamic inter omaximizethesurfaceareaforinput,weplacedthesensorabovetheelbow,leavingthe ent annamingtheinputlocations,aswasdoneinthepreviouslydescribed conditions,weemploy ckerstomarkinputtargets.Thiswasbothtoreduce confusion (since locations on t ot have common names) and to increase input consistency. As mentioned pr we believe the forearm is ideal for projected interface elements;thesti owtechplaceholdersforprojectedbuttons. DESIGNANDSETUP Weemployedawithinsubjects ticipantperformingtasksineachofthe fiveconditionsinrandomizedorder:fivefingersw ow;fivepointsonthewhole armwiththesensorsabovetheelbow;thesamepointswithsens ed andblind;andtenmarkedpointsontheforearmwiththesensorsabovetheelbow. 11

Participantswereseatedinaconventionalofficechair,infrontofadesktopcomputerthat orconditionswithsensorsbelowtheelbow,weplacedthearmband~3cmaway fromtheelbow, rtheradiusandtheotherneartheulna.Forconditions withthesensorsabovetheelbow,w heelbow,suchthatone sensorpackagerestedonthebiceps.Righthandedparticipantshadt ft arm,whichallowedthemtousetheirdominanthandforfingerinput.Fortheonelefthan dthesetup,whichhadnoapparenteffectontheoperationofthesystem. Tightness of t sted to be firm, but comfortable. While performing tasks, participants cou e their elbow on the desk, tucked against their body, or on the cha mrest;mostchosethelatter. Procedure Foreachcondition,theexperimenterwalkedthrough onstobetestedand demonstrated finger taps on each. Participants practiced these motions for approximatelyoneminutewitheachgestureset.Thisallowedpartic rizethemselves withournamingconventionsandtopracticetappingtheirarmandhandswith ehand.Italsoallowedustoconveytheappropriatetapforcetoparticipants,whooften in arilyhard. Totrainthesystem,participantswereinstructedtocomfortablytapeachlocati ingeroftheirchoosing.Thisconstitutedonetraininground.Intotal,threeroundsoftrain tedperinputlocationset(30examplesperlocation,150datapointstotal).An exceptiont aseofthetenforearmlocations,whereonlytworoundswere collectedtosavetime(20exam ointstotal).Totaltrainingtimeforeach experimentalconditionwasapproximatelythreemi hetrainingdatatobuildanSVMclassifier.Duringthesubsequenttestingphase, wepresent hsimpletextstimuli(e.g.tapyourwrist),whichinstructedthem wheretotap.Theorder heachlocationappearingtentimesintotal. Thesystemperformedrealtimesegmentationan ndprovidedimmediatefeedback to the participant. We provided feedback so tha pants could see where the system was makingerrors.Ifaninputwasnotsegmente ldseethisandwouldsimplytap again.Overall,segmentationerrorrateswerenegligiblein tincludedinfurther analysis. 12

Accuracyofthethreewholearmcentricconditions.Errorbarsrepresentstandarddeviation.

RESULTS Inthis section,wereportontheclassificationaccuracies forthetestphases i conditions. Overall, classification rates were high, with an average acc cross conditionsof87.6%.Additionally,wepresentpreliminaryresultsexploringthecorrel en classificationaccuracyandfactorssuchasBMI,age,andsex. FiveFingers Despite mu sings and ~40cm ofseparation between the input targets and sensors, classificat acy remained high for the fivefinger condition, averaging 87.7% (SD=10.0%, %)acrossparticipants.Segmentation,asinotherconditions,wasessentially perfect. Insp onfusionmatricesshowednosystematicerrorsintheclassification,with errorstendingto utedovertheotherdigits.Whenclassificationwasincorrect,the systembelievedtheinput er60.5%ofthetime;onlymarginallyaboveprior probability(40%).Thissuggeststhereare ccontinuitiesbetweenthefingers. Theonlypotentialexceptiontothiswasinthecaseof gerconstituted 63.3%percentofthemisclassifications. WholeArm Participants performe conditions with the wholearm location configuration. The belowelbow place ormed the best, posting a 95.5% (SD=5.1%, chance=20%) average 13

accuracy.Thisisnotsurprising,asthisconditionplacedthesensorsclosertotheinputta ditions.Movingthesensorabovetheelbowreducedaccuracyto88.3%(SD=7.8%, chance=20%), lmostcertainlyrelatedtotheacousticlossattheelbowjoint andtheadditional10cmofd randinputtargets.Figure8showsthese results. The eyesfree input condition yi uracies than other conditions, averaging 85.0% (SD=9.4%, chance=20%). This r ents a 10.5% drop from its vision assisted, but otherwiseidenticalcounterp on.Itwasapparentfromwatchingparticipantscompletethis conditionthattargetingprecis .Insightedconditions,participantsappearedtobe abletotaplocations with perhaps a lthough notformallycaptured,this marginoferrorappearedtodoubleortriplewhenthee vethatadditional trainingdata,whichbettercoverstheincreasedinputvariability,would sdeficit. Wewouldalsocautiondesignersdevelopingeyesfree,onbodyinterfacestocaref cationsparticipantscantapaccurately.

Forearm Classificationaccuracyforthetenlocationforearmconditionstoodat81.5%(SD=10 10%),asurprisinglystrongresultforaninputsetwedevisedtopushoursystemssensing ment,weconsidereddifferentwaystoimproveaccuracybycollapsingthe ten locations int pings.Thegoal ofthis exercisewas toexplorethetradeoff betweenclassificationaccur utlocationsontheforearm,whichrepresentsa particularlyvaluableinputsurfaceforappl rs.Wegroupedtargetsintosetsbasedon 14

whatwebelievedtobelogicalspatialgroupings.Inadditiontoexploringclassificationacc youts that we considered to be intuitive, we also performed an exhausti (programmatically)overallpossiblegroupings.Formostlocationcounts,thissearchconfirm intuitive groupings were optimal; however, this search revealed one plausib lthough irregular,layoutwithhighaccuracyatsixinputlocations. Unlikeinthefivefin reappearedtobesharedacoustictraitsthatledtoa higher likelihood of confusion argets than distant ones. This effect was more prominentlaterallythanlongit igure9illustratesthiswithlateralgroupingsconsistently outperforming similarly arr longitudinal groupings. This is unsurprising given the morphologyofthearm,wi eofbilateralsymmetryalongthelongaxis. BMIEffects Earlyon,wesuspectedthatourac ptibletovariationsinbody composition.Thisincluded,mostnotably,theprevalenceoffat nsity/massof bones.These,respectively,tendtodampenorfacilitatethetransmissionofa he body. To assess how these variations affected our sensing accuracy, we ed each participantsbodymassindex(BMI)fromselfreportedweightandheight.Dataand xperimentsuggestthathighBMIiscorrelatedwithdecreasedaccuracies.Theparticipants wi estBMIsproducedthethreelowestaverageaccuracies.Figure10illustratesthis significan eparticipantsareseparatedintotwogroups,thosewithBMIgreaterand lessthantheUSna justed(F1,12=8.65,p=.013). Otherfactorssuchasageandsex,whichmaybecorrelatedtoB ons, mightalsoexhibitacorrelationwithclassificationaccuracy.Forexample,inourpart lesyieldedhigherclassificationaccuraciesthanfemales,butweexpectthatthisisanarti ioninoursample,andprobablynotaneffectofsexdirectly. SUPPLEMENTALEXPERIMENTS We ofsmaller, targetedexperiments toexplore the feasibility ofour approachforother nthefirstadditionalexperiment,whichtestedperformanceofthe systemwhileuserswalked itedonemale(age23)andonefemale(age26)fora singlepurposeexperiment.Fortherest edsevennewparticipants(3 15

female,meanage26.9)fromwithinourinstitution.Inallcases,thesensorarmbandwasplac imilartothepreviousexperiment,eachadditionalexperimentconsistedofa trainingphase, antsprovidedbetween10and20examplesforeachinputtype,anda testingphase,inwhich dtoprovideaparticularinput.Asbefore,input orderwasrandomized;segmentationandcla rformedinrealtime. WalkingandJogging As discussed previously, acousticallydrive echniques are often sensitive to environmentalnoise.Inregardtobioacousticsens rscoupledtothebody,noise createdduringothermotionsisparticularlytroublesome,and epresentperhaps the most common types of wholebody motion. This experiment he accuracy of our systeminthesescenarios. Eachparticipanttrainedandtestedthe gandjoggingonatreadmill. Threeinputlocationswereusedtoevaluateaccuracy:arm,wri lly,therateof falsepositivesandtruepositiveswascaptured.Thetestingphasetookrou mplete.Themalewalkedat2.3mphandjoggedat4.3mph;thefemaleat1.9and3.1mph, res ,thesystemneverproducedafalsepositiveinput.Meanwhile, true positive accuracy ssification accuracy for the inputs (e.g., a wrist tap was recognizedasa %forthemaleand86.7%forthefemale(chance=33%). Inthejoggingtrials,thesystemhad nts(twoperparticipant) over six minutes of continuous jogging. Truepositive as with walking, was 100%. Consideringthatjoggingisperhapsthehardestinput ntationtest,weviewthis resultasextremelypositive.Classificationaccuracy,however,d 3%and60.0%forthe maleandfemaleparticipantsrespectively. Althoughthenoisegenerate mostcertainlydegradedthesignal,we believethechiefcause forthis decrease wasthe ing data. Participants only providedtenexamplesforeachofthreetestedinputlocation hetrainingexamples werecollectedwhileparticipantswerejogging.Thus,theresultingtra tonlyhighly variable,butalsosparseneitherofwhichisconducivetoaccuratemachine . Webelievethatmorerigorouscollectionoftrainingdatacouldyieldevenstrongerresult tures Intheexperiments discussedthus far,weconsideredonlybimanualgestures,wheret

sensorfreearm,andinparticularthefingers,areusedtoprovideinput.However,thereare nbeperformedwithjustthefingersofonehand.Thiswasthefocusof[2], althoughthis ationaccuracy. We conducted three independent tests to explore onehanded ge The first had participantstaptheirindex,middle,ringandpinkyfingersagainstth hing gesture) ten times each. Our system was able to identify the four s with an overall accuracyof89.6%(SD=5.1%,chance=25%).Werananidenticalexperim steadof taps(i.e.,usingthethumbasacatch,thenrapidlyflickingthefingersforward). ive96.8%(SD=3.1%,chance=25%)accuracyinthetestingphase.

Thismotivatedustorunathirdandindependentexperimentthatcombinedtapsandflicks in rticipantsretrainedthesystem,andcompletedanindependenttesting round.Evenwitheigh ryclosespatialproximity,thesystemwasabletoachievea remarkable 87.3% (SD=4.8%, accuracy. This result is comparable to the aforementioned ten location xperiment (which achieved 81.5% accuracy), lending credence to the possibili having ten or more functions on the hand alone. Furthermore, propriocep gersonasinglehandisquiteaccurate,suggestingamechanismforhigh accuracy,eyesfree ctRecognition Duringpiloting,itbecameapparentthatoursystemhadsomeabilitytoident alonwhichtheuserwasoperating.Usingasimilarsetuptothemainexperiment,weasked p eir index finger against 1) a finger on their other hand, 2) a pape ately 80 pages thick, and 3) an LCD screen. Results show that we ca e contactedobjectwithabout87.1%(SD=8.3%,chance=33%)accuracy.Thiscapabilitywasneve hendesigningthesystem,sosuperioracousticfeaturesmayexist.Evenasaccuracy 17

standsnow,thereareseveralinterestingapplicationsthatcouldtakeadvantageofthisfunc luding workstations or devices composed of different interactive surfaces, cognition of differentobjectsgraspedintheenvironment. IdentificationofFingerTapT rfaceswiththeirfingersinseveraldistinctways.Forexample,onecanuse thetipofthei ntheirfingernail)orthepad(flat,bottom)oftheirfinger.The formertendstobequit eshy.Itisalsopossibletousetheknuckles (bothmajorandminormetacarpophalangealjoin pproachsabilitytodistinguishtheseinputtypes,wehadparticipantstapon atablesitua ays:fingertip,fingerpad,andmajorknuckle.Aclassifier trainedonthisdatayieldedan %(SD=4.7%,chance=33%)duringthe testingperiod. Thisabilityhasseveralpotentialuses. otableistheabilityforinteractive touchsurfacestodistinguishdifferenttypesoffinge mpleinteractioncouldbe thatdoubleknockingonanitemopensit,whileapadtapacti ngerInput A pragmatic concern regarding the appropriation of fingertips for was that other routinetaskswouldgeneratefalsepositives.Forexample,typingonake nger tipsinaverysimilarmannertothefingertipinputweproposedpreviously.Thus,we ertofingerinputsoundedsufficientlydistinctsuchthatotheractionscouldbe disregarde essment,weaskedparticipantstotaptheirindexfinger20timeswitha fingerontheirot faceofatableinfrontofthem.Thisdatawas usedtotrainourclassifier.Thistraining se,whichyieldeda participantwideaverageaccuracyof94.3%(SD=4.5%,chance=50%). EXAMP NDINTERACTIONS We conceived and built several prototype interfaces that dem e our ability to appropriate the human body, in this case the arm, a an interactive surface. These interfacescanbeseeninFigure11,aswellasinthea

Whilethebioacousticinputmodalityisnotstrictlytetheredtoaparticularoutputmodalit orformfactorsweexploredcouldbereadilycoupledwithvisualoutputprovided byaninteg herearetwonicepropertiesofwearingsuchaprojectiondeviceon the arm that permi many calibration issues. First, the arm is a relatively rigid structure enattachedappropriately,willnaturallytrackwiththearm.Second, sincewehavefinegra ,makingminuteadjustmentstoaligntheprojected imagewiththearmistrivial. Toillust ingprojectionandfingerinputonthebody(asresearchers haveproposedtodowithproject asedtechniques[19]),wedeveloped threeproofofconceptprojectedinterfacesbuiltontop utclassification.In thefirstinterface,weprojectaseriesofbuttonsontotheforearm, pto navigateahierarchicalmenu(Figure11,left).Inthesecondinterface,weprojectas ,whichausercannavigatebytappingatthetoporbottomtoscrollupanddownoneitem editemactivatesit.Inathirdinterface,weprojectanumeric keypadonauserspalmand alaphonenumber(right).To emphasizetheoutputflexibilityofapproach,wealsocoupled udiooutput. Inthiscase,theusertapsonpresetlocationsontheirforearmandhandtona diointerface. 19

CONCLUSION Inthispaper,wehavepresentedourapproachtoappropriatingthehumanbodyas have described a novel, wearable bioacoustic sensing array that we bu armbandinordertodetectandlocalizefingertapsontheforearmandhand.Resultsfromour atoursystemperformsverywellforaseriesofgestures,evenwhenthe bodyisinmotion. edinitialresultsdemonstratingotherpotentialuses ofourapproach,whichwehopetofurt ork.Theseincludesinglehanded gestures,tapswithdifferentpartsofthefinger,anddiff enmaterialsandobjects. Weconcludewithdescriptionsofseveralprototypeapplicationsth etherichdesign spacewebelieveSkinputenables. 20

REFERENCES 1. Ahmad,F.,andMusilek,P.AKeystrokeandPointerControlInputInterfacefor ers.InProc.IEEEPERCOM06,211. 2. Amento,B.,Hill,W.,andTerveen,L.TheSoundofO cFingertipGestureInterface.InCHI02Ext.Abstracts,724725. 3. Argyros, A.A., and A. Visionbased Interpretation of Hand Gestures for RemoteControlofaComputer CV2006WorkshoponComputerVision inHCI,LNCS3979,4051. 4. Burges,C.J.ATutorialon rPatternRecognition.DataMining andKnowledgeDiscovery,2.2,June1998,121167. 5. Cli nes on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obe lts.NationalHeart,LungandBloodInstitute.Jun.17,1998. 6. Deyle, T., Palinko, S ., and Starner, T. Hambone: A BioAcoustic Gesture Interface.InProc.ISWC 0 ebis,G.,Nicolescu,M.,Boyle,R.D.,andTwombly,X.Visionbasedhandpose estimation:Ar nandImageUnderstanding.108,Oct.,2007. 8. Fabiani, G.E. McFarland, D.J. Wolpaw, Pfurtscheller, G. Conversion of EEG activityintocursormovementbyabraincomp CI).IEEETrans.onNeural SystemsandRehabilitationEngineering,12.3,3318.Sept.2004. 21

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5814)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- IoTeX Whitepaper 1.5 ENDocument40 pagesIoTeX Whitepaper 1.5 ENprila hermantoNo ratings yet

- Abstract of Cloud ComputingDocument6 pagesAbstract of Cloud ComputingJanaki JanuNo ratings yet

- 12F Lab Manual 2022Document70 pages12F Lab Manual 202211F10 RUCHITA MAARANNo ratings yet

- G Code ListDocument3 pagesG Code ListRautoiu AndreiNo ratings yet

- ITQ VDI Design Guide Special FREE EditionDocument367 pagesITQ VDI Design Guide Special FREE EditionAli Dayani100% (1)

- Simple Sqli DumperDocument8 pagesSimple Sqli DumperAlex RozackNo ratings yet

- Layers (Lecture 53)Document26 pagesLayers (Lecture 53)amjad aliNo ratings yet

- Autoflame PC Software GuideDocument102 pagesAutoflame PC Software GuideSebastianCastilloNo ratings yet

- Xample Program in C++ Using File Handling To Perform Following OperationsDocument6 pagesXample Program in C++ Using File Handling To Perform Following OperationsNamita SahuNo ratings yet

- Lecture CH 2 Sec 110Document46 pagesLecture CH 2 Sec 110Gary BaxleyNo ratings yet

- Excel ShortcutsDocument230 pagesExcel ShortcutsPavan LalwaniNo ratings yet

- Company Contact DetailsDocument30 pagesCompany Contact DetailsERKATHIRNo ratings yet

- ICT Grade 7 UAEDocument85 pagesICT Grade 7 UAEfalasteen.qandeelNo ratings yet

- SEPM Unit 1 - Final - pptx-1Document113 pagesSEPM Unit 1 - Final - pptx-1Dj adityaNo ratings yet

- D TechnologiesDocument33 pagesD TechnologiesClubedoTecnicoNo ratings yet

- OcbDocument95 pagesOcbneeraj kumar singh100% (2)

- E-Commerce Website Using Mern StackDocument6 pagesE-Commerce Website Using Mern StackprathamNo ratings yet

- Navigating PCI DSS v4.0Document24 pagesNavigating PCI DSS v4.0Ivan DoriNo ratings yet

- Crucetas TOYO Con Medidas PDFDocument5 pagesCrucetas TOYO Con Medidas PDFFrancisco Javier Moreira CórdobaNo ratings yet

- Punjabi University, Computer Science DepartmentDocument9 pagesPunjabi University, Computer Science DepartmentAbdela Aman MtechNo ratings yet

- SysTrack Solution BriefDocument4 pagesSysTrack Solution BriefArun GuptaNo ratings yet

- 003 041e 3.0Document2 pages003 041e 3.0Ahmed El-ShafeiNo ratings yet

- Kamran HashmiDocument2 pagesKamran HashmihasanNo ratings yet

- Business Analyst Interview QuestionsDocument2 pagesBusiness Analyst Interview Questionspgsbe33% (3)

- Why You Should Use EyecatchersDocument5 pagesWhy You Should Use EyecatchersAtthulaiNo ratings yet

- FactoryTalk View Site Edition Tips and Best Practices TOCDocument7 pagesFactoryTalk View Site Edition Tips and Best Practices TOCKevin PeñaNo ratings yet

- WordSmith Tools Manual V 6.0Document448 pagesWordSmith Tools Manual V 6.0RynkoNo ratings yet

- Carel Eev Evd0000e00Document48 pagesCarel Eev Evd0000e00evrimkNo ratings yet

- Linked List: Data Structure and AlgorithmsDocument36 pagesLinked List: Data Structure and AlgorithmsRitesh JanaNo ratings yet

- Appendix A 2Document7 pagesAppendix A 2MUNKIN QUINTERONo ratings yet