Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Foreign Women Test Solomon's Wisdom

Uploaded by

argirocanoOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Foreign Women Test Solomon's Wisdom

Uploaded by

argirocanoCopyright:

Available Formats

Biblical Interpretation

Biblical Interpretation 15 (2007) 135-150

www.brill.nl/bi

She Came to Test Him with Hard Questions: Foreign Women and Their View on Israel

Susanne Gillmayr-Bucher

RWTH Aachen University

Abstract

Focusing on two foreign women, the queen of Sheba (1 Kings 10) and Rahab the prostitute ( Joshua 2), this article shows how their otherness is shaped and used as a literary tool. Both women are introduced as strangers, but simultaneously they are portrayed with characteristic traits of good Israelites. The multifarious literary image of these women are used as a mirror for Israel. Hence inside and outside, self and other, and also superiority and inferiority are intermingled. Whereas the women themselves vanish from the stories, the interwoven aspects of their literary otherness cast a new light on Israel and its self-perception.

In the stories of the Old Testament foreigners are not usually portrayed very favourably, least so, foreign women. Most of them are only mentioned as temptresses who lead the Israelites astray and seduce them to turn away from their own way of life, their wisdom, and their own religion. In these texts the portrait of an Israelite identity seems to be based on a sharp contrast between the self and the other. The biblical texts do not only display a xenophobic discourse but they also make literary use of otherness in order to highlight some aspects of their self-conception. Nevertheless there are texts which show foreigners as amicable and a few foreign women are even presented as acceptable according to Israelite standards. However, these narrations do not focus on the women themselves, but make specific use of their female otherness. They carefully lay out the womens roles emphasising their difference. Furthermore, by underlining the point of view of these foreign women as a perspective from outside, the narrators add a new dimension to the story. It sets the narrated events in a wider perspective, and adds new elements to

Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, 2007 DOI: 10.1163/156851507X181138

book_15-2.indb 135

6-3-2007 15:01:40

136

S. Gillmayr-Bucher / Biblical Interpretation 15 (2007) 135-150

the narrative. Although these strange women seem to be characterised according to an idealised depiction of foreignness, they are not just turned into good foreigners or integrated into the people of Israel,1 but their foreignness is combined with a point of view supporting Israelite interests. Their image thus unfolds as a vivid dialogue of different voices.2 Focusing on the stories of two quite different foreign women, the queen of Sheba (1 Kings 10), and Rahab, the prostitute from Jericho ( Joshua 2), I want to trace the different and interwoven aspects of their literary otherness. Queen of Sheba The story of the queen of Sheba unfolds as a simple story.3 It is set in the middle of several notes about the fabulous wealth of king Solomon (1 Kgs 9:26-10:29). The queen of Sheba sets out with a mighty entourage to test the wisdom of Solomon.4 When she arrives and talks to him, she sees his palace, his food, his servants, as well as his offerings, and she finds everything that she has previously heard confirmed. Even more so, she is overwhelmed by seeing how well Solomon is doing. After a generous exchange of presents the queen departs. Although the story unfolds straightforwardly the literary role of the queen of Sheba is multifaceted.

1)

A total integration of foreigners into Israel is anticipated only in the book of Isaiah. However, such foreigners have to adopt an Israelite way of life and faith. They have to abandon their otherness to be fully integrated. See Lang 1996: 33. 2) Bakhtin describes such a dialogue as typical for a character zone. The area occupied by an important characters voice must in any event be broader than his direct and actual words...it is always, to one degree or another, dialogized. Bakhtin 1981: 320. 3) Sheba is usually identified with the south-west Arabian Saba. This area was famous for its trade in incense and other aromatics. International trade by caravan between Saba and Mesopotamia is documented from the eighth century bce. However, queens are only known to have come from the north-west of the Arabian peninsula. There, queens were well established from the eighth to early seventh century bce (Kitchen 1997: 127-143). The queen of Sheba in 1 Kings 10 might thus be a literary combination of the fabulous riches from the Sabeans and the lore of the north-west Arabian queens. 4) 1 Kgs 10:1-10,13 belongs to the wisdom stories in the Solomon tradition. Like king Solomon, the queen of Sheba is shown as a wise monarch. As wisdom was considered to be an ideal feature for a monarch, the portrait of the queen of Sheba follows a well-known representation. See Wlchli 1999: 129-159.

book_15-2.indb 136

6-3-2007 15:01:41

S. Gillmayr-Bucher / Biblical Interpretation 15 (2007) 135-150

137

Explicit and implicit role models shape her appearance in the story. She is shown as a queen, a monarch, a wise and strange woman, a critic as well as an admirer of Solomon and his deity Yhwh. It is the intersection of these different roles and their connotations that establishes the literary function of the foreign queen. The Queen as a Ruler. In the story of Solomon (1 Kings 3-10) the queen of Sheba is shown as one of the many foreign rulers who come to admire Solomons wisdom and bring their gifts and tributes (1 Kings 5:10-14). Thus the queen of Sheba is clearly marked as a foreign ruler on a state visit.5 Nonetheless, the queen of Sheba does not fit perfectly into that image. From Israels point of view, a queen is a foreign concept. Hence, as a queen, she is even more foreign than her male counterparts; she is a stranger among strangers. Moreover, the image of the visiting monarch is enhanced. The queen does not only come to hear Solomons wisdom (1 Kgs 5: 14) but to test it. Another feature that is emphasised is her strength. Her large entourage stresses her military power. She is a powerful queen that arrives with lyj dbk, an expression usually referring to a mighty army.6 Furthermore, the things she carries with her bear witness to her wealth. She came with camels carrying balsam oil, large quantities of gold, and precious stones (v. 2).7 In addition her wisdom is of such a standing that she wants to test Solomon (twdyjb wtsnl abtw).8 She is the one who applies a standard and assesses the wisdom of another king. The queens voice is an authoritative voice. The image of a wise,9 wealthy and powerful queen is formed accordingly, one who combines the best features a monarch may have. Consequently she is portrayed as totally independent from Solomon

5)

Kings making long journeys to visit another ruler were commonplace. See Kitchen 1997: 142. 6) Cf. 2 Kgs 6:14; 18:17; Isa. 36:2. 7) This notion hints at the riches of Saba and its caravan trade. 8) To speak to someone in riddles reveals a form of speech from the wisdom tradition (Prov. 1:6). See Camp 2000: 175. 9) Camp sees the wise queen as a narrative transmutation of Proverbs Woman Wisdom. She even continues: True to this role, she fulfils Yahwehs earlier promise by bringing the riches and honor that should accompany Solomons choice for wisdom. (Camp 2000: 175).

book_15-2.indb 137

6-3-2007 15:01:41

138

S. Gillmayr-Bucher / Biblical Interpretation 15 (2007) 135-150

and she has nothing to fear or to gain, which enables her to claim the liberty of free and honest speech. The power-settings are reversed in this story. Solomon is not necessarily shown as the wisest of all kings. In this encounter he has to compete with a queen, and it has to be proven that he is her equal. Within the Solomon story this is news. The prevailing image, which shows Solomon as the greatest of all kings, is abandoned and has to be confirmed again. The dialogue between the narrating voice and the queen of Sheba that constitutes this story is not shaped by submission or dominance. Even though the queen is a powerful stranger, the narrating voice tries to present her and Solomons voice as equal voices. To strengthen this impression the narrating voice protects and shapes Solomons voice. Together they compete against the queen.10 The story tries to present a well-balanced power structure, yet the way the story is told suggests that at least a slight uncertainty still remains. Solomon is not the unquestionable great king. The Strange Woman. The image of the strange woman is not fully explored in this story, but it is alluded to. The queen of Sheba is evocative of the tempting and desirable woman, a woman Solomon might want to impress. Nonetheless, a possible lovestory is repressed in the biblical text,11and there are no explicit allusionsquite contrary to later legends that embellished this story as a love-story on a grand scale.12 The encounter with the queen of Sheba gains further tension and ambiguity from the juxtaposition with ch. 11. Thus the queen of Sheba is contrasted with some hundred foreign women who are strongly accused of seducing Solomon, leading him away from his deity.13 In

The dialogue between the narrating voice and the voice of the queen of Sheba is shaped as a double voiced dialogue splitting the voice of authority. While the narrating voice demands authority it still has to compete with the queens voice. And even though the queen is partially muted, her voice is still present. Cf. Bachtin 1979: 157, 183. 11) In the foreground there is the power of wisdom; in the background there is a seductive strangeness that can be suppressed but not eliminated; (Camp 2000: 176). 12) The story of the encounter between king Solomon and the queen of Sheba has been extensively elaborated in Jewish, Arabian and Ethiopian traditions. Cf. Ullendorff 19623; Pennacchietti 2000. 13) In the books of Chronicles, 1 Kings 11 is omitted. Consequently the visit of the

10)

book_15-2.indb 138

6-3-2007 15:01:41

S. Gillmayr-Bucher / Biblical Interpretation 15 (2007) 135-150

139

contrast to all the other foreign women mentioned in relation to king Solomon the queen of Sheba is not portrayed as a possible wife or concubine for Solomon. Instead she is kept at a distance so that her foreignness and the threatening voice of the strange woman do not interfere. From Critic to Admiration. The queen of Sheba is introduced by the narrating voice as a critic, who has come to test king Solomon. She sees the other, the foreign king she has heard of, as a provocation and turns herself into a challenge for Solomon.14 However, we are never allowed to hear her discussion with Solomon. Rather the narrating voice tells about the meeting between queen and king, and, in this case, merely summarises the outcome of the queens questions: she came to Solomon and talked with him about all that she had on her mind. Solomon answered all her questions; nothing was too hard for the king to explain to her (v. 2). Additionally, the narrating voice allows insight into the perception of the queen, telling us what she saw at Solomons palace (vv. 45) and concluding: there was no breath (jwr) left within her (v. 5). Only after the narrating voice finishes its detailed description of her perception is the queen herself allowed to talk. She starts with a reference to a voice that has not been heard before, a particular report the queen has heard about Solomon. She then compares this report with the things she saw herself and she concludes that what she has seen is even much better than the rumour she had heard. While the queen of Sheba is shown in great detail the voice of Solomon is not heard. Furthermore, the real challenge the queen stands for, the testing of Solomons wisdom with riddles, is not depicted. The story unfolds as a dialogue between the narrating voice and the voice of the queen of Sheba. In the end the queen supports with her words everything the narrating voice informs us about Solomon. So the queen of Sheba is portrayed as a critic, who has been convinced. In her praise of Solomon, she then expresses all the admiration that is expected from

queen of Sheba becomes even more so the climax of Solomons peaceful and prosperous reign; Schearing 1997: 445. 14) Waldenfels points out that otherness commences a dialogue; Waldenfels 1997: 77.)

book_15-2.indb 139

6-3-2007 15:01:41

140

S. Gillmayr-Bucher / Biblical Interpretation 15 (2007) 135-150

a foreign monarch on a state visit. Hence she confirms that Solomon is among the greatest of kings. The queens praise fulfils an important function within the whole story of Solomon. She not only attests Solomon to be one of the greatest kings of his time, she further justifies his reign. When she starts praising Solomon, she explicitly points out his wisdom (vv. 7-8), not only what she saw of Solomons riches and wealth. She goes on to expand her praise when she includes Yhwh (v. 9). In her words she refers to the voice of Hiram (1 Kgs 4:22) and to Gods voice in ch. 3, giving Solomon the wisdom to rule his people (1 Kgs 3:9,12-13). The queen of Sheba proves to be well informed and, even more surprising, to be in accordance with Solomons point of view. In praising God for making Solomon king of Israel, she confirms something that is very important to Solomons reign. It is never mentioned that God put Solomon on the throne within the Solomon story; rather, God merely acknowledged him there. Although Solomon demands the throne quite self-confidently for himself (1 Kgs 8:20) and several reviews emphasise the promise to David that his son will succeed him (1 Kgs 3:6; 5:19; 8:25; 9:5) the queens voice, designed as an impartial voice, gives strong support to this claim.15 As a result the queen is presented as someone who is able to give a review, to combine all elements, to form a coherent picture andmost importantto draw the right conclusions. The Queen and Yhwh? From the very beginning this story connects the queen of Sheba and Yhwh, the deity of Israel. The text starts with a reference to Yhwh: When the queen of Sheba heard about the fame of Solomon for the name of Yhwh (v. 1). Thus the rumours about Solomon, which set the queen in motion, are connected to Yhwh. Furthermore the text is anxious to show that the queen is thoroughly convinced and even enthusiastic about what she sees and perceives. Accordingly, Solomons worship of Yhwh as well as Yhwh and his decisions are included in this evaluation.

In Chronicles the story of the queen of Sheba gains further importance because several other examples of Solomons wisdom are omitted. Thus the visit takes a new significance and becomes a major demonstration of Solomons political and economic sagacity. L. Schearing, A wealth of women, p. 445.

15)

book_15-2.indb 140

6-3-2007 15:01:42

S. Gillmayr-Bucher / Biblical Interpretation 15 (2007) 135-150

141

The queens point of view corresponds to the perspective of the narrating voice. This is obvious when she talks about Yhwh (v. 9). The queen refers to Yhwh as Solomons god and then continues to evaluate what Yhwh does. Although she is shown as an outsider and foreigner she is able to do so. Thus the queen assumes a privileged point of view. This is something which is usually reserved for the narrating voiceif expressed from a distant point of viewor someone personally engaged with Yhwh. The queen of Sheba furthermore has excellent knowledge of Solomon and his relationship to Yhwh and also of Yhwhs relationship with Israel. The evaluation that she offers is the perspective that the whole story of Solomon tries to establish. In this manner the queen gains even more authority since she creates the impression that she has certain superior skills for evaluation at her disposal. At the same time, the queen of Shebas relation to Yhwh is questioned. Is she someone who acknowledges this deity, who admires or even worships Yhwh? However, the text does not provide any clear and unequivocal evidence. The queen of Sheba still remains an ambiguous woman. The story of the queens visit is placed at the end of Solomons success story, and it is the culmination and reversal point in one. The approval of a wise, powerful and wealthy queen of Sheba strongly supports Solomons reputation as a monarch. However, the fact that the most elaborate description of a state visit presents a queen and not a king adds a dimension of strangeness and unpredictability to this story. Being a foreign woman of the upper nobility the queen of Sheba foreshadows a turning point. The distance between king Solomon and the queen of Sheba, which the narrative voice strictly maintains, is essential. Only the narrating voice is involved in a communication with the queen. It thereby forms a shield between her and Solomon. Hence the queens riddles only raise doubts and foreshadow events to come. Once the barrier is removed king Solomon falls for the foreign women (1 Kings 11). The queen of Sheba is portrayed as an iridescent person in a vivid dialogue of different images. On the one hand, she remains the foreign queen and she alludes to the strange woman. On the other hand, she is presented as a wise woman, who is able to evaluate Solomons kingdom not only according to secular matters, but also with reference to

book_15-2.indb 141

6-3-2007 15:01:42

142

S. Gillmayr-Bucher / Biblical Interpretation 15 (2007) 135-150

Solomons deity. And that is why she evaluates Solomons reign and the achievements of his kingdom in terms of Yhwhs delight and his love for Israel. In this narration the queen of Sheba is used as a benchmark. Her otherness functions as a mirror that reflects Solomons greatness and confirms and emphasises his election. Once more the image of what might have been is evoked (Viviano 1997:347). The mixture of the images of a strange woman, a powerful queen and an authoritative voice which evaluates Solomon and his reign makes the queen such a dazzling and simultaneously challenging woman. Rahab The second portrayal of a foreign woman I want to focus on is that of Rahab ( Joshua 2). Again the main protagonist is a foreign woman belonging to a small social group. As a hnwz hva Rahab is also an independent woman, who does not belong to anybody. The story begins when Joshua sends out two men to reconnoitre the situation in Jericho. Rahab enters this story when these two men come to her house. Soon after their arrival, the king of Jericho is told that spies have arrived and he requests their extradition. Rahab, however, protects the two men; she hands false information to the persecutors and helps the spies to escape unharmed. In between these events a discourse develops between Rahab and the spies. In this discourse Rahab reflects upon the history and future of Israel as well as negotiating terms for her rescue in return for her help. Again, the roles in which Rahab appears are ambiguous, creating a manifold portrayal of this woman. Rahab the Prostitute. When Rahab is first mentioned in the story (v. 1) she is introduced as hnwz hva, a prostitute and/or an innkeeper.16 As a hnwz hva Rahab lives on the margin of society. She is tolerated but stigmatized, desired but ostracized (Bird 1989:121; Jost 1994:127-28). The house of a hnwz hva is open for everybody, no questions asked.17

Bird points out that the association of prostitutes with taverns or beer houses is well attested in Mesopotamian texts; Bird 1989: 128. 17) On the other hand, this openness is matched by a limited acceptability. A prostitute

16)

book_15-2.indb 142

6-3-2007 15:01:42

S. Gillmayr-Bucher / Biblical Interpretation 15 (2007) 135-150

143

Even evildoers will find a place there (Isa. 1:21). In the eyes of the prophets a hnwz hva lacks loyalty, she quickly follows her new lovers (e.g. Jer. 2:20; Ezekiel 16; Hosea 2) and she turns to those who pay her for her services (e.g. Deut. 23:19; Mic. 1:7; Ezekiel 16, Hosea 2). Nevertheless, the unfolding of this story totally depends on Rahabs social status. Only because Rahab is a hnwz hva, foreign men have access to her, and only because she lives on the outer periphery of the city and the margin of society is she able to help the spies in the way she does (Bird 1989:130). From the Canaanites point of view Rahab proves herself to be a typical hnwz hva. Her house is open for everyone, she helps her customers and she shows no loyalty to her king or her people. Instead she seeks her own advantage. However, this is not the point of view of the story! For the spies, and thus for the readers who follow their point of view, Rahab shows a quite unexpected loyalty to Israel and its deity.18 From this perspective Rahab even offers hospitality. Therefore Rahabs role is twofold: she is a prostitute and simultaneously acts as a hostess.19 She is only able to offer hospitality because she is a prostitute. Hence Rahab goes beyond both roles and combines them in a new and surprising manner. Rahab the Strange Woman. Being a foreign and strange woman Rahab evokes a sense of danger; she is seductive and she might lead the spies astray. Consequently the house of the prostitute is a potentially dangerous place (cf. Prov. 29:3). Although it might be a smart manoeuvre to rest in an unobtrusive place, this house is, nevertheless,

is not approved as a wife for everybody; e.g. priests are not allowed to marry her. Cf. Lev. 21:7, 14. 18) This might have been the first stratum of this story: a prostitute protecting foreign spies from being discovered, assisting their flight and in return demanding to be protected herself. She opts for an extra safeguard. While nobody knows that she protected the foreign spies she is safe within her own town, with her own people; should they, however, be overpowered by the Israelites, she has also taken precautions for her protection. Cf. Fritz 1993: 34; see also Noort 1998: 131-146. 19) Just like any good host Rahab offers protection to her guests. But she offers hospitality to dangerous foreigners as well, people who are not usually offered hospitality. See Hobbs 2001: 23, 28.

book_15-2.indb 143

6-3-2007 15:01:42

144

S. Gillmayr-Bucher / Biblical Interpretation 15 (2007) 135-150

perilous. The sexual aspect of the spies visit, however, is not displayed but only alluded to. On the other hand, Rahab as an inhabitant of Jericho is endangered herself by the Israelites. Deuteronomy stipulates clearly and precisely how to treat the inhabitants of the promised land (Deut. 7:1-5). Therefore it appears as a surprising turn in the story, when Rahab provides asylum for the spies and encourages their mission with explicit references to their own set of beliefs. And equally surprising is the spies promise to spare her and grant her dsj.20 Rahab the Belonging Woman. The dialogue between Rahab and the messengers of the king of Jericho, who request that the spies be turned over, forms the background to Rahabs addressing of the two spies. While talking to the messengers Rahab twice states ytody al (vv. 4-5).21 When Rahab opens her speech to the spies in v. 9 with an accentuated ytody this forms a contrast to the first dialogue. So far, the readers have no idea why Rahab acted as she did, why she offered hospitality to her enemies. In this way the dramatic tension of the story is increased and has to be released in the following speech.22 Rahab starts with a declarative statement: I know that Yhwh has given this land to you (v. 9). The most surprising aspect is that this information is stated as something that has already happened. Rahab leaves no room for any doubt as to whether Yhwh will help. She continues with an analysis of the emotional experience of her fellow countrymen: and that a great fear of you has fallen on us, so that all who live in the land are melting (in fear) before you. The next verse (v. 10) provides a retrospective explanation. Rahab tells the history of Israel starting with the events at the Red Sea and then summarises Israels campaign against Sihon and Og, the two kings of the Amorites east of the Jordan, who have been completely destroyed (Mrj; Num. 21:21-35; 32:33; Deut. 1:4; 31:4; Josh. 9:10). And yet Rahab formulates her statement not only as her exclusive insight but

20) In contrast to this agreement Joshua 7 highlights the order that nothing must be spared from the Mrj (cf. Deut. 7:2; 20:16-17). 21) The second denial is therefore certainly a false statement and the first one may be. 22) The dialogue between Rahab and the spies is probably an addendum from a deuteronomistic redaction. This changes the focus of the whole story. Cf. Stek 2002: 34.

book_15-2.indb 144

6-3-2007 15:01:42

S. Gillmayr-Bucher / Biblical Interpretation 15 (2007) 135-150

145

also as a common understanding: For we have heard (v. 10), pointing to a Canaanite voice or at least a generalised voice from Jericho (cf. Josh. 9:9-10). It is quite unusual that Rahab, a Canaanite, is portrayed as someone who is able to summarise not only the most recent Israelite history but as someone who starts with the most important event, the delivery from Egypt, and, furthermore, interprets all these events as great deeds of Israels deity. This speech portrays Rahab with the words of a deuteronomistic theologian. When compared to the song of Moses at the Red Sea (Exod. 15:15-16) this is even more obvious. In her review (vv. 9-10) Rahab uses the same words and cites the same motives, and thus indicates that the hopes expressed by Moses have become true. Rahabs retrospection and reflection is concluded with another declarative statement: for Yhwh your God is God in heaven above and on the earth below (v. 11). The long address of Rahab shows a clear structure: starting with a subjective statement: I knowshe goes on and enlarges her perspective during a recollection of Israels history: we have heardand finally arrives at a general statement: Yhwh, the god of heaven and earth (cf. Deut. 4:39). With this avowal Rahab ends the first part of her speech and, she moreover, establishes a basis for her following request.23 In v. 12 a new part of Rahabs speech begins. It is only now that she refers to her own situation and links it to her acting on behalf of the two men. At the time when the Israelites will conquer Jericho, she requests to be saved just as she has saved the spies. She asks for dsj, as she herself has shown dsj (vv. 12-13; cf. Gen. 21:23; Judg. 8:35; 2 Sam. 2:6; 10:2=1 Chron. 19:2). Calling her own act dsj, Rahab establishes a bond of obligation with the spies.24 Rahab negotiates as an equal partner. By requesting a vow by Yhwh she emphasises her role as a belonging party. The two men accept Rahabs argument and promise to act according to her demands. Rahab successfully moves the border between herself and the spies, between self and other. She, the stranger, offers an identity narrative for the Israelites, and places herself with them.25

23) 24)

See Welke-Holtmann 2005: 166. Bird 1989: 129. Her strategy worked, she and her family were spared from the Mrj. Cf. Frymer-Kensky 1997: 63. 25) For a depiction of the identity narrative see Martin 1995: 7-9.

book_15-2.indb 145

6-3-2007 15:01:43

146

S. Gillmayr-Bucher / Biblical Interpretation 15 (2007) 135-150

Rahab an Israelite Spy. The spy motif functions as a frame for this story. The full impact of this frame can be seen clearly at the end of Joshua 2. In their report to Joshua the spies repeat verbatim Rahabs words. But now it is apparent that the most important information they could get hold of is Rahabs analysis of the current situation. With this final report the similarity to another spy story in Numbers 13-14 emerges as well. There Moses had sent out men to explore the land of Canaan and when they returned, they gave a very pessimistic report. Although they had seen the beauty and fertility of the land, their estimation was devastating: We cannot attack those people; they are stronger than we are... We seemed like grasshoppers in our own eyes, and we looked the same to them (Num. 13:31-33). Compared to this report the most important achievement of the secret action related in Joshua 2 is not a detailed description of the land, its people, fortified cities etc., but an estimation of the prospects of a conquest. Whereas in Numbers 13 most of the spies considered the chances to be very small, Rahab offers a totally different vision. She encourages a military action like Caleb and Joshua (Num. 13:30; 14:7-9 cf. Frymer-Kensky 1997:58-59). She reverses the report of Numbers 13: the Canaanites are not overconfident, they do not rely on their superiority; instead they are trembling with fear (vv. 9, 11). Even before any doubts are expressed Rahab offers her story as a competing narrative,26 convincing the spies to identify with her point of view and subsequently to accept Rahab as one of their own.27 Thereby Rahabs otherness enhances the universal validity of an Israelite point of view. The spies value these thoughts as an insider view and offer them as the heart of their conclusions to Joshua. Focusing on the spies, Rahabs expertise does not lack a bit of a humorous streak.28 Whereas concentrating on Rahab reveals that she is portrayed similarly to Caleb and Joshua, the only ones who were not

On the idea of identity as a choice see Martin 1995: 13-15. Rahab tries to establish her own identity with her narration as well. Frymer-Kensky reasons that this resourceful outsider, Rahab the trickster, is a new Israel; Frymer-Kensky 1997: 61. See also Wierlacher 2003: 290. 28) Zakovitch classifies Joshua 2 as a parody of a spy story; Zakovitch 1990: 95.

27)

26)

book_15-2.indb 146

6-3-2007 15:01:43

S. Gillmayr-Bucher / Biblical Interpretation 15 (2007) 135-150

147

frightened but set their faith in Yhwh (Num. 14:7-9), with reference to Numbers 13-14 Rahab is portrayed as the exemplary Israelite spy.29 Rahab is presented in complex and multifaceted terms. She combines elements of the dangerous strange woman, the unreliable prostitute, but simultaneously she appears as the faithful and wise theologian and the capable informant. She is the strange and foreign woman on the side of Israel.30 She offers hospitality, protection and insight, and in return she asks not to share the fate of all other strangers. Thus Rahab becomes an example of a good stranger, even an excellent stranger, and one who justifies an extraordinary exceptionto be spared from the Mrj.31 Nonetheless, Rahab only asks for dsj and to be allowed to live but does not seek inclusion into Israel.32 Rahab adopts an Israelite discourse. While the narrating voice alludes to a standard spy story, it is Rahab, the anticipated other, who takes over a typical Israelite point of view and discourse. Her otherness is used as a literary element: on the one hand, it functions within the story to strengthen the validity of an Israelite point of view. On the other hand, Rahabs real otherness is repressed. She is not portrayed as Canaanite woman, but as an Israelite theologian disguised as the other. Set at the beginning of the book of Joshua, this story gains further importance. Before all the native inhabitants of the land promised to Israel are driven away and annihilated, the story of an exception is told in great detail. It is the story of a strange woman, but nevertheless, a woman who belongs. Thus the conquest of the land is not shown as a one-sided event only, but, within narrow limits, as the beginnings of a new mixture, and potentially a new definition of we/us and the other. However, the dialogue of power still prevails. The definition of inside and outside shifts from a strict affiliation through birth to an affiliation based on ideology and belief.

29) It is the mission of spies to gain access to the non-accessible and thus to reduce its strangeness. Rahab fulfils this demand for her own interests as well as for Israel. 30) Quite similar to the foreign prophetic voice of Balaak, Numbers 22-24. 31) This exception is emphasised in Joshua 6:17, 22-23. 32) Only Joshua 6:25 carries this story on and states that Rahab lived in the midst of Israel unto this day.

book_15-2.indb 147

6-3-2007 15:01:43

148

S. Gillmayr-Bucher / Biblical Interpretation 15 (2007) 135-150

Conclusions The biblical portrayal of these two quite different foreign women shows how otherness may be used as a literary tool. Both stories make use of the foreign woman to emphasise a certain quality of the Israelites, especially their superiority. Nevertheless, both women act from a superior position themselves. Told from a point of view where there is still some uncertainty concerning the Israels standing, the foreign women are used to dispel any doubts. As they mirror the Israelite position, its supremacy becomes obvious.Even though the women are main characters in these stories, their portrayal remains fragmentary and their otherness is only roughly sketched. Their own attitude and cultural identity is abandoned in favour of a theological statement, which confirms and supports an Israelite point of view. Even the dangerous aspect of the foreign woman that forms the background of both narratives is repressed and diminished. As characters these women do not endure, they are absorbed or depart from the story. From the point of view of a dominant discourse, however, these atypical foreign women undermine a position that not only distinguishes between self and other but also evaluates such a differentiation as normative and necessary. Thus in the end quite a complex situation has been created: on the level of the plot the Israelite position is (slightly) inferior and the foreign woman appears in a superior position. On the level of discourse it is reversed: here the Israelite discourse is dominating and the genuine voice of the foreigner, the other, is suppressed and silenced.33 On the level of the story Israel hopes to persist and prosper in spite of powerful others. On the level of discourse, however, the existence of others in light of and despite a xenophobic Israelite discourse is at stake. Bibliography

Bakhtin, Mikhail 1981 Discourse in the Novel, in Michael Holquist, The Dialogic Imagination: Four essays by M. M. Bakhtin (Austin: University of Texas press): 259-422.

33)

What remains of the other is usurped and adopted as ones own; Waldenfels 1997: 48-

50.

book_15-2.indb 148

6-3-2007 15:01:43

S. Gillmayr-Bucher / Biblical Interpretation 15 (2007) 135-150

149

Bachtin, Michail 1979 Das Wort im Roman, in Michail Bachtin, Die sthetik des Wortes (Frankfurt: Suhrkamp): 154-300. Bird, Phyllis 1989 The Harlot as Heroine: Narrative Art and Social Presupposition in Three Old Testament Texts, Semeia 46: 119-139. Camp, Claudia V. 2000 Wise, Strange and Holy: The Strange Woman and the Making of the Bible ( JSOTSup, 320; Gender, Culture, Theory, 9; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press). Fritz, Volkmar 1993 Das Buch Josua (Handbuch zum Alten Testament 7; Tbingen: Mohr). Frymer-Kensky, Tikav 1997 Reading Rahab, in Mordechai Cogan; Barry L. Eichler; Jeffrey H. Tigay, (eds.), Tehillah le-Moshe: Biblical and Judaic Studies in Honor of Moshe Greenberg (Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns): 57-67. Hobbs, T. R. 2001 Hospitality in the First Testament and the teleological fallacy , JSOT 95: 3-30. Jost, Renate 1994 Von Huren und Heiligen: Ein Sozialgeschichtlicher Beitrag, in Feministische Hermeneutik und Erstes Testament: Analysen und Interpretationen (Stuttgart: Kohlhammer): 126-137. Kitchen, Kenneth A. 1997 Sheba and Arabia, in Lowell K. Handy (ed.), The Age of Solomon. Scholarship at the Turn of the Millennium (Studies in the History and Culture of the Ancient Near East 11; Leiden: Brill): 126-153. Lang, Bernhard 1996 Die Fremden in der Sicht des Alten Testaments, in Rainer Kampling and Bruno Schlegelberger (eds.), Wahrnehmung des Fremden: Christentum und anderre Religionen (Schriften der Disesanakademie Berlin 12; Berlin: Morus): 9-37. Martin, Denis-Constant 1995 The Coices of Identity, Social Identities 1: 5-20. Noort, Edward 1998 Das Buch Josua: Forschungsgeschichte und Problemfelder (Ertrge der Forschung 292; Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft). Pennacchietti, Fabrizio A. 2000 The Queen of Sheba, the Glass Floor and the Floating Tree-Trunk, in Henoch 22: 223-246. Schearing, Linda S. 1997 A Wealth of Women: Looking Behind, Within, and Beyond Solomons Story, in Handy (ed.), The Age of Solomon: 428-456. Stek, John H. 2002 Rahab of Canaan and Israel: The Meaning of Joshua 2, Calvin Theological Journal 37,1: 28-48. Ullendorff, Edward 1962-63 The Queen of Sheba, in Bulletin of the John Rylands Library 45: 486-504. Wlchli, Stefan 1999 Der weise Knig Salomo. Eine Studie zu den Erzhlungen von der Weisheit Salomos in Ihrem Alttestamentlichen und Altorientlischen Kontext (Beitrge zur Wissenschaft vom Alten und Neuen Testament 141; Stuttgart: Kohlhammer). Waldenfels, Bernhard 1997 Topographie des Fremden: Studien zur Phnomenologie des Fremden I (Frankfurt: Suhrkamp). Welke-Holtmann, Sigrun 2005 Die Kommunikation zwischen Frau und Mann. Dialogstrukturen in den Erzhltexten der Hebrischen Bibel (Exegese in unserer Zeit, 13; Mnster: Lit.

book_15-2.indb 149

6-3-2007 15:01:43

150

S. Gillmayr-Bucher / Biblical Interpretation 15 (2007) 135-150

Wierlacher, Alois 2003 Kulturwissenschaftliche Xenologie, in Ansgar Nnning and Vera Nnning (eds.), Konzepte der Kulturwissenschaften: Theoretische Grundlagen AnstzePersepktiven (Stuttgart: Metzler): 280-306. Viviano, Pauline A. 1997 Glory Lost: The Reign of Solomon in the Deuteronomistic History, in Handy (ed.), The Age of Solomon: 336-347. Zakovitch, Yair 1990 Humor and Theology or the Successful Failure of Israelite Intelligence: A Literary-Folkloric Approach to Joshua 2, in Susan Niditch (ed.), Text and Tradition. The Hebrew Bible and Folklore (The Society of Biblical Literature; Semeia Studies; Atlanta, GA: Scholars Press): 75-98.

book_15-2.indb 150

6-3-2007 15:01:44

You might also like

- Leon Morris The Apostolic Preaching of The CrossDocument162 pagesLeon Morris The Apostolic Preaching of The Crossargirocano100% (16)

- Queen of ShebaDocument3 pagesQueen of Shebahotman68100% (2)

- Dictionary of The Later New Testament & Its Developments (The IVP Bible Dictionary Series) 1997aDocument660 pagesDictionary of The Later New Testament & Its Developments (The IVP Bible Dictionary Series) 1997aHerbert Adam Storck83% (12)

- All Books of EnochDocument119 pagesAll Books of Enochdouglasray2150100% (3)

- Djypsy Djazz Djam BookDocument234 pagesDjypsy Djazz Djam BookAntoniousBlock100% (3)

- Queen of Sheba: A Captivating Guide to a Mysterious Queen Mentioned in the Bible and Her Relationship with King SolomonFrom EverandQueen of Sheba: A Captivating Guide to a Mysterious Queen Mentioned in the Bible and Her Relationship with King SolomonNo ratings yet

- The Queen of ShebaDocument6 pagesThe Queen of ShebaFaris Alarshani100% (1)

- Queen of ShebaDocument23 pagesQueen of ShebawalebtsmNo ratings yet

- Performative BetrayalsDocument10 pagesPerformative BetrayalsSouss OuNo ratings yet

- Makeda The Queen of Sheba SabaDocument7 pagesMakeda The Queen of Sheba SabaMULENGA BWALYANo ratings yet

- Solomon The Trickster Biblical InterpreDocument9 pagesSolomon The Trickster Biblical InterpreChiến GiuseppeNo ratings yet

- 1 and 2 ChroniclesDocument15 pages1 and 2 ChroniclesJefferson KagiriNo ratings yet

- On The Historical Solomon: Understanding The Solomon Narrative in 1 Kings 1-11 in Light of Deuteronomy 17:14-20Document19 pagesOn The Historical Solomon: Understanding The Solomon Narrative in 1 Kings 1-11 in Light of Deuteronomy 17:14-20Sid Sudiacal100% (2)

- Queen HerodDocument3 pagesQueen HerodShamerah Theivendran100% (1)

- Audio Review #3Document3 pagesAudio Review #3Aner Mercado GabrielNo ratings yet

- Solomons Ring PDFDocument39 pagesSolomons Ring PDFHameed SaeedNo ratings yet

- The Expositor's Bible: The Song of Solomon and the Lamentations of JeremiahFrom EverandThe Expositor's Bible: The Song of Solomon and the Lamentations of JeremiahNo ratings yet

- Book of 1 KingsDocument14 pagesBook of 1 Kingsrdmello09No ratings yet

- Sabine M. L. Van Den Eyndem, If Esther Had Not Been That Beautiful: Dealing With A Hidden God in The (Hebrew) Book of EstherDocument6 pagesSabine M. L. Van Den Eyndem, If Esther Had Not Been That Beautiful: Dealing With A Hidden God in The (Hebrew) Book of EstherJonathanNo ratings yet

- Character SketchDocument6 pagesCharacter SketchReginah KaranjaNo ratings yet

- 3rd Quarter 2015 Lesson 3 Easy Reading Edition The Unlikely MissionaryDocument7 pages3rd Quarter 2015 Lesson 3 Easy Reading Edition The Unlikely MissionaryRitchie FamarinNo ratings yet

- King SolomonDocument9 pagesKing SolomonTimothy100% (1)

- The Queen of ShebaDocument6 pagesThe Queen of ShebaIwan SuryolaksonoNo ratings yet

- The Missiological ImplicationsDocument2 pagesThe Missiological ImplicationsGoran JovanovićNo ratings yet

- Beowulf FemDocument14 pagesBeowulf FemLaura Rejón LópezNo ratings yet

- The Rise of MonarchyDocument6 pagesThe Rise of MonarchyṬhanuama BiateNo ratings yet

- JeremiahDocument12 pagesJeremiahe4unityNo ratings yet

- Black Women Are Beautiful and Fair Beyond Measure - Vanguard NewsDocument5 pagesBlack Women Are Beautiful and Fair Beyond Measure - Vanguard NewsMike MichaelNo ratings yet

- Binary Opposition in Fairy Tales: Insight Into The Working of IdeologyDocument8 pagesBinary Opposition in Fairy Tales: Insight Into The Working of IdeologyAnika Reza100% (3)

- Queen HerodDocument4 pagesQueen HerodTalia AbdelwahabNo ratings yet

- bilqis, the queen of shebaDocument19 pagesbilqis, the queen of shebaNikita KohliNo ratings yet

- Noeli Serna 6 December, 2010 Professor Wall Removing The Elizabethan' From Elizabethan EnglandDocument9 pagesNoeli Serna 6 December, 2010 Professor Wall Removing The Elizabethan' From Elizabethan EnglandNoeli SernaNo ratings yet

- Women in Prophetic and Wisdom TraditionsDocument6 pagesWomen in Prophetic and Wisdom TraditionsLem Suantak100% (1)

- Shemot - NamesDocument6 pagesShemot - NamesDavid MathewsNo ratings yet

- 1001 Nights and Persian LiteratureDocument8 pages1001 Nights and Persian LiteratureKatya0046No ratings yet

- MalvolioDocument15 pagesMalvolioঅর্ক কোথায়0% (1)

- The Kings of Israel and Judah: A Captivating Guide to the Ancient Jewish Kingdom of David and Solomon, the Divided Monarchy, and the Assyrian and Babylonian Conquests of Samaria and JerusalemFrom EverandThe Kings of Israel and Judah: A Captivating Guide to the Ancient Jewish Kingdom of David and Solomon, the Divided Monarchy, and the Assyrian and Babylonian Conquests of Samaria and JerusalemNo ratings yet

- Uncovering Linguistic Traces Between Ugaritic and Old Arabic DialectsDocument21 pagesUncovering Linguistic Traces Between Ugaritic and Old Arabic DialectsWesley Muhammad100% (1)

- Lucifera 1.1Document5 pagesLucifera 1.1Emily ChazenNo ratings yet

- The Court, The Rule, and The Queen: Faerie As A Representation of ElizabethDocument15 pagesThe Court, The Rule, and The Queen: Faerie As A Representation of ElizabethAnithaNo ratings yet

- The Two House IsraelDocument17 pagesThe Two House IsraelHaSophim100% (7)

- Subtly Highlight The Hushing of The Female: Gender in Simone de Beauvoir's Second Sex) (New York)Document3 pagesSubtly Highlight The Hushing of The Female: Gender in Simone de Beauvoir's Second Sex) (New York)coremathsNo ratings yet

- Solomon and The Royal Art of LoveDocument6 pagesSolomon and The Royal Art of LoveIvan TrosseroNo ratings yet

- Carr Conway - Introduction To The Bible - Chapter 03Document33 pagesCarr Conway - Introduction To The Bible - Chapter 03esonamtsoloNo ratings yet

- Memoirs of an Arabian Princess: An Accurate Translation of Her Authentic VoiceFrom EverandMemoirs of an Arabian Princess: An Accurate Translation of Her Authentic VoiceNo ratings yet

- Patai LilithDocument20 pagesPatai LilithCassio Saga100% (1)

- The Shulamite, the Shepherd, and Solomon: Lessons from the Song of SolomonFrom EverandThe Shulamite, the Shepherd, and Solomon: Lessons from the Song of SolomonNo ratings yet

- Kruk Warrior Women PDFDocument18 pagesKruk Warrior Women PDFHana TuhamiNo ratings yet

- Female Soveraynetee' in Chaucer's The Wife of Bath's Prologue and Tale'Document4 pagesFemale Soveraynetee' in Chaucer's The Wife of Bath's Prologue and Tale'Mariana KanarekNo ratings yet

- Female 'soveraynetee' in Chaucer's 'Wife of BathDocument4 pagesFemale 'soveraynetee' in Chaucer's 'Wife of BathMariana KanarekNo ratings yet

- Did Ancient Israel Have Queens?Document10 pagesDid Ancient Israel Have Queens?Pa-NehesiBenYahudiEl100% (1)

- God's Role in the Book of JudgesDocument22 pagesGod's Role in the Book of Judgeswolg67No ratings yet

- A Pentecostal Paradigm For The Latin American Family PDFDocument12 pagesA Pentecostal Paradigm For The Latin American Family PDFargirocanoNo ratings yet

- Galatians A T RobertsonDocument39 pagesGalatians A T RobertsonargirocanoNo ratings yet

- The New Testament Use of The Old TestamentDocument20 pagesThe New Testament Use of The Old Testamentsizquier66100% (4)

- Genre and Historical ConsiderationsDocument4 pagesGenre and Historical ConsiderationsargirocanoNo ratings yet

- El Templo Symbol and ControversyDocument13 pagesEl Templo Symbol and ControversyargirocanoNo ratings yet

- El Templo Symbol and ControversyDocument13 pagesEl Templo Symbol and ControversyargirocanoNo ratings yet

- El Templo Symbol and ControversyDocument13 pagesEl Templo Symbol and ControversyargirocanoNo ratings yet

- El Templo Symbol and ControversyDocument13 pagesEl Templo Symbol and ControversyargirocanoNo ratings yet

- Biblia Nestle 1904Document688 pagesBiblia Nestle 1904argirocanoNo ratings yet

- Genre and Historical ConsiderationsDocument4 pagesGenre and Historical ConsiderationsargirocanoNo ratings yet

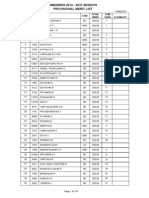

- Final Merit List MAFSUDocument504 pagesFinal Merit List MAFSUPravin DeokarNo ratings yet

- Te, 'Wall 144 C I - T9.7R7U Ofcar: - Rrq7 Cilgpi - SDocument11 pagesTe, 'Wall 144 C I - T9.7R7U Ofcar: - Rrq7 Cilgpi - SNabilaNo ratings yet

- LỚP 8 MÔN TIẾNG ANH BÀI TẬP ÔN THI HỌC KÌ 1Document25 pagesLỚP 8 MÔN TIẾNG ANH BÀI TẬP ÔN THI HỌC KÌ 1tran voNo ratings yet

- Der Mac On 2011Document42 pagesDer Mac On 2011menoloveNo ratings yet

- Simple Past QuestionDocument2 pagesSimple Past QuestionAlexandre RodriguesNo ratings yet

- Biblical Discrepancies Acts PaulDocument2 pagesBiblical Discrepancies Acts Paulprevo015No ratings yet

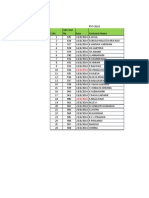

- LET0916ps eDocument119 pagesLET0916ps ePRC Board85% (20)

- Right To Information-List of Appellate Authority, Pios and Apios of Kwa ErnakulamDocument6 pagesRight To Information-List of Appellate Authority, Pios and Apios of Kwa ErnakulammanugeorgeNo ratings yet

- Step 3 Social ST 2nd Term North America 2019Document17 pagesStep 3 Social ST 2nd Term North America 2019Anonymous QA1y3WVNo ratings yet

- Pornstar List From A To ZDocument1 pagePornstar List From A To Zmr88dzc752No ratings yet

- Tom Cruise Was On The Cover of Five Major American Magazines When His Latest Movie Was Released Earlier This SummerDocument2 pagesTom Cruise Was On The Cover of Five Major American Magazines When His Latest Movie Was Released Earlier This Summerrocio martinezNo ratings yet

- Prayer For Preparation To StudyDocument12 pagesPrayer For Preparation To StudyCzareena DominiqueNo ratings yet

- TN MBBS BDS Merit ListDocument787 pagesTN MBBS BDS Merit ListAnweshaBoseNo ratings yet

- 2nd Quarter Exam in CHRISTIAN LIVING FinalDocument2 pages2nd Quarter Exam in CHRISTIAN LIVING FinalManuel LisondraNo ratings yet

- Memoirs of a Revolutionary GeneralDocument4 pagesMemoirs of a Revolutionary GeneralBeatriz NideaNo ratings yet

- Sep CallsDocument16 pagesSep CallsSatyarohini SravanthiNo ratings yet

- Convergys Recruitment Process For JKC 2011 Pass Outs (Rangareddy, Hyderabad, Medak and Mahaboobnagar Districts)Document66 pagesConvergys Recruitment Process For JKC 2011 Pass Outs (Rangareddy, Hyderabad, Medak and Mahaboobnagar Districts)Rakesh KumarNo ratings yet

- My Favorite MoviesDocument4 pagesMy Favorite MoviesSava ObradovicNo ratings yet

- 201838Document3 pages201838ShubhamNo ratings yet

- Naga Treditional Instruments/ Quarterly Research Progress ReportDocument19 pagesNaga Treditional Instruments/ Quarterly Research Progress ReportD.A ChasieNo ratings yet

- Mooney Service CentersDocument13 pagesMooney Service Centersjose aguilarNo ratings yet

- Digital Booklet - Underclass HeroDocument8 pagesDigital Booklet - Underclass HeroLeovardo Aquino100% (2)

- History of Architecture 4 - ReviewerDocument53 pagesHistory of Architecture 4 - ReviewerAdriana Walters100% (1)

- EREE 2022-2023 ConcoursDocument6 pagesEREE 2022-2023 ConcoursNAJEM GRMNo ratings yet

- Harry Potter QuestionsDocument8 pagesHarry Potter QuestionsAF BorziNo ratings yet

- TG 1 30 Dec 2014Document53 pagesTG 1 30 Dec 2014Nur Azila ZailanNo ratings yet

- 2aryan Pandavas 08589173-Asko-Parpola-Pandaih-and-Sita-On-the-Historical-Background-on-the-Sanskrit-Epics PDFDocument9 pages2aryan Pandavas 08589173-Asko-Parpola-Pandaih-and-Sita-On-the-Historical-Background-on-the-Sanskrit-Epics PDFsergio_hofmann9837No ratings yet

- Thoughts On The Creation Myths of The Cree, The Mohawk, and The CherokeeDocument6 pagesThoughts On The Creation Myths of The Cree, The Mohawk, and The CherokeeChad Alan NicholsNo ratings yet