Professional Documents

Culture Documents

BR. The Anjou Bible

Uploaded by

davidluna19813894Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

BR. The Anjou Bible

Uploaded by

davidluna19813894Copyright:

Available Formats

REVIEWS

587

Lieve Watteeuw and Jan Van der Stock, eds. The Anjou Bible: A Royal Manuscript Revealed.

Corpus of Illuminated Manuscripts 18. Low Countries Series 13. Documenta Libraria 39. Leuven: Peeters, 2010. xii + 336 pp. index. illus. bibl. 85. ISBN: 978 90 429 2445 1.

Cathleen A. Fleck. The Clement Bible at the Medieval Courts of Naples and Avignon: A Story of Papal Power, Royal Prestige, and Patronage.

Farnham: Ashgate Publishing Limited, 2010. xx + 350 pp. + 4 color pls. index. illus. tbls. map. bibl. $124.95. ISBN: 978 075466 9807.

Neapolitan studies have recently seen a significant upsurge in international activity with conferences, monographs, articles, and collections of essays on art, architecture, urbanism, political and religious thought, court culture, and the digitization of archival collections. Two recent publications bring to bear the insights from this new research on manuscript studies. The Anjou Bible presents a splendid collection of twelve essays focusing on K. U. Leuven, Maurits Sabbe Library, Ms 1 (the Anjou or Malines Bible). This has been published in conjunction with an exhibition and colloquium on the Bible in November 2010 stemming from its stabilization, restoration, and digitization. The essays cover codicology (Gistelinck, Dequeker, Delsaerdt, Watteeuw); technical examination of the manuscript, its construction and archaeology, including a fascinating discussion of quantitative hyperspectral imaging (Padoan et al.); artistic technique (Watteeuw and Van Bos); genre (Lowden); Angevin visual culture (Tomei and Paone, Bock); patronage (Fleck); the politics of art under Robert the Wise and his heirs (Duran); and Cristoforo Orimina as artist (Perriccioli Saggese). The essays are accompanied by generous annotations, brief biographies of Robert and Giovanna I, a comprehensive bibliography, and reproductions of all the illustrated folios with calendar, but no index. The manuscript is one of the most lavish and well-known illustrated Bibles of the later Middle Ages. It was probably commissioned in the late 1330s by King Robert and largely completed by 1340 by two of the courts artists, the scribe Iannucius de Matrice and the illuminator Cristoforo Orimina. Orimina is also responsible for about forty Neapolitan illuminated manuscripts, including several other outsized Bibles, such as the Hamilton Bible (Berlin, Kupferstichkabinett, Ms78. E.3), the Planisio Bible (BAV Vat. Lat. 3550), and perhaps the Clement Bible (BL Ms. Add. 47672; see below). The Anjou Bible was probably intended as a wedding present for Roberts granddaughter and heir, Giovanna I, and his grandnephew, Andrew of Hungary, but it was completed under the patronage of

588

RENAISSANCE QUARTERLY

` dAlife, at Queen Giovannas request royal counselor and later chancellor, Niccolo after Andrews assassination in 1345. The painting-over of Andrews coats of arms with dAlifes provides poignant evidence of this transfer. DAlife then bequeathed the Bible to the Celestine house of the Ascension before his death in 1367. By 1402 it already appeared in the inventory of Jean, Duc de Berry. It may have made its way to France via the Celestines or via Giovannas close political and symbolic ties with the Valois, as Vitolo has recently demonstrated (see my review, RQ 62.1 [2009], 200 201). After Jeans death it was sold in Paris in 1418 to Bishop Nicolas Ruterius of Arras, who bequeathed it to the Arras College of Leuven on his death in 1509. After the colleges suppression in 1797 the Bible was transferred to the episcopal seminary at Mechelen (Malines) where it had been cataloged by 1821. Spared the destruction of Leuvens collections in 1914 and 1940, since 1970 it has been part of onard, Alessandra Perricioli the theology facultys Maurits Sabbe Library. Emile Le Saggese, and Millard Meiss helped draw international attention to it. Restoration began in 2008. There are miniature portraits of the royal family throughout, including the frontispiece portrait of Robert enthroned among the virtues overcoming the vices (3v ), the famed Angevin pictorial genealogy (4r ), Robert commissioning the Bible (217r ), and a delightful scene of Robert and Queen Sancia playing chess (257r ). The tender miniatures of young Giovanna and Andrew conversing (249r ) and out riding (278r ) also counter the early slanders of their mutual disdain and then open hostility used as circumstantial evidence for the queens purported role in Andrews brutal murder. Certain historiographical traditions strive against one another here, including what I have termed elsewhere the black legend of the Angevins: the blood- and guilt-soaked conquest by Charles I, Roberts usurpation of the throne (Lowden, 12; Duran, 74, etc.), Andrews disinheritance (Lowden 13, 27; Duran, 74; contradicted by Fleck, 40, 48; and Paone, 71n121), Giovannas murder of Andrew (Lowen 23, 28), and the collapse of the kingdom and its cultural life during her wanton and incompetent rule. This publication is thus of major importance for the greater clarity it provides for Giovannas reign, her piety, and her onard, of dynastic agency. Here we possess evidence, long ago emphasized by Le both the queens moral education and the important political and propaganda machinery that was placed at her disposal by King Robert through such objects as the Anjou Bible. But Roberts anxieties, expressed clearly and repeatedly in this Bible, were not about his own legitimacy (this had been settled years before, and by the pope himself), but about the premature death of his son and heir Charles of Calabria in 1328 and the problematic inheritance of the crown by a woman within the French and Angevin royal lines. It was Giovannas right to the throne not Roberts or the Angevin dynastys that is visually bolstered here. Given the great beauty of these folios, the wealth of historical information offered in their illustrations, and the restricted access to the physical codex, the mixed publication plan of the volume makes great sense. This generous and important print volume is accompanied by an even more beautiful online, open-access version of the

REVIEWS

589

illustrated folios, presented in a high-resolution image viewer at: http://www. anjoubible.be/thebibleonline. Cathleen A. Flecks excellent and insightful biography of the Clement Bible (BL Ms. Add. 47672), based on her dissertation completed under Herbert Kessler and her own extensive published work, also offers an intriguing tale of discovery and analysis. While she employs several traditional codicological techniques, she also deploys a social commodity approach borrowed from anthropology (Mauss on gifts, Appadurai and Kopytoff on singularity and social meaning of artifacts) and Campbells theory of cultural translation. Fleck traces the Bibles life from its creation in Naples ca. 1330 34, perhaps once again as a gift for Andrew of Hungary. Without ascribing it to Orminia, she places it firmly in the Neapolitan cavalliniano context both on stylistic grounds and through the prominence of apocalyptic themes and imagery analyzed by Emmerson and Lewis, focusing on the BabylonJerusalem duality. Using Willimans archival research and database, Fleck is able to trace its later possession by Abbot Raymond de Gramat of Monte Cassino, its consequent seizure as spoil by Benedict XII on Raymonds death in 1340, its (less convincingly argued) role in the papal palace at Avignon and appropriation by Clement VII, its sojourn with antipope Benedict XIII in Aragon and its return to Naples after antipope Clement VIII granted it to Alfonso V (I of Naples). She then quickly surveys its disappearance, reappearance in France in 1788, purchase by the earl of Leicester in 1816 and acquisition by the British Museum in 1952. She employs a new methodology for manuscript studies that focuses as much on arthistorical questions and approaches (patronage, stylistics, schools and influence, materials and techniques), which we see at work in the analysis of the Anjou Bible, as on the shifting valences of meaning attached to context, diachronicity, and exchange. Fleck demonstrates the continuity of artistic tradition, style, and personnel between Naples, Rome, and Avignon in the Trecento and the common visual language (and secular and religious iconography) shared by painting and manuscript illumination during this period, establishing value through social and cultural context. She emphasizes the apocalyptic imagery and the political symbolism of Jerusalem as key to the tension inherent in the Roman bishops prolonged residence in Avignon and Trecento criticisms (including those of Dante, Petrarch, and Cola di Rienzo) of that Babylonian exile. Her interpretation derives partly from Elliott and Warrs recent studies on Sta. Maria Donna Regina, partly on her original interpretation of the angelic hierarchies and King Roberts role in the beatific vision controversy, and partly on theories of Neapolitan court culture as propaganda, following Kelly. Given Flecks heavy emphasis on context, Queen Sancia of Majorcas absence from these pages is surprising. Nonetheless, Flecks insightful research and original methodologies convincingly confirm what Bruzelius (Queen Sancia of Mallorca and the Church of Sta. Chiara in Naples, Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome, 40 [1995]) and this reviewer (Queen Sancia of Naples [1286 1345] and the Spiritual Franciscans, in Women of the Medieval World, ed. Kirshner and Wemple [1985]; Franciscan Joachimism at the Court of

590

RENAISSANCE QUARTERLY

Naples, 1309 1345: a new appraisal, Archivum Franciscanum Historicum 90 [1997]) saw as the essentially apocalyptic if not Joachite court culture fostered by Robert and Sancia in letters and sermons, their support of the Spiritual Franciscans and their construction of Sta. Chiara at precisely the period of this Bibles composition. Apropos both volumes under review, this reviewer has cautioned elsewhere (RQ 57 [2004], 984 85) that one should not make too much of the Burckhardtian theory (via Greenblatt) of Renaissance identity creation in the service of legitimization, an interpretation of King Robert forcefully argued by Kelly and restated by Fleck. Robert was less looking forward to models of invented Renaissance personas than fitting into a long tradition of pious medieval rulers, their virtues, devotion, and ambitions (emphasized by Duran, Bock, and Paone). Nor ought one to overstate Bruzeliuss thesis of French influence, which she herself has recently nuanced in favor of more local and mendicant models. On the whole, however, the rich scholarly findings and consequent dialog reflected in both these books makes them highly valuable as evidence of the healthy international state of Neapolitan studies.

RONALD G. MUSTO

Italica Press

Copyright of Renaissance Quarterly is the property of University of Chicago Press and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.

You might also like

- The Arnolfini Betrothal: Medieval Marriage and the Enigma of Van Eyck's Double PortraitFrom EverandThe Arnolfini Betrothal: Medieval Marriage and the Enigma of Van Eyck's Double PortraitNo ratings yet

- The "True Story" of The Abba Gärima GospelsDocument3 pagesThe "True Story" of The Abba Gärima Gospelsmessay admasuNo ratings yet

- Gatti in A Space Between Varmundo SacramentoDocument41 pagesGatti in A Space Between Varmundo SacramentodanaethomNo ratings yet

- 121347-Article Text-244291-1-10-20220823Document4 pages121347-Article Text-244291-1-10-20220823Jean75No ratings yet

- Curatos As A CustodianDocument9 pagesCuratos As A CustodianRevista Feminæ LiteraturaNo ratings yet

- The Transformation of a Religious Landscape: Medieval Southern Italy, 850–1150From EverandThe Transformation of a Religious Landscape: Medieval Southern Italy, 850–1150No ratings yet

- Ottonian ArtDocument12 pagesOttonian ArtLKMs HUBNo ratings yet

- Unceasing Strife, Unending Fear: Jacques de Thérines and the Freedom of the Church in the Age of the Last CapetiansFrom EverandUnceasing Strife, Unending Fear: Jacques de Thérines and the Freedom of the Church in the Age of the Last CapetiansRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- Malcolm Lambert The Cathars PDFDocument5 pagesMalcolm Lambert The Cathars PDFTeresa KssNo ratings yet

- Religious Women in Early Carolingian Francia: A Study of Manuscript Transmission and Monastic CultureFrom EverandReligious Women in Early Carolingian Francia: A Study of Manuscript Transmission and Monastic CultureNo ratings yet

- Studies From Court and Cloister (Barnes & Noble Digital Library)From EverandStudies From Court and Cloister (Barnes & Noble Digital Library)No ratings yet

- L'Antiquité Tardive Dans Les Collections Médiévales: Textes Et Représentations, VI - Xiv SiècleDocument22 pagesL'Antiquité Tardive Dans Les Collections Médiévales: Textes Et Représentations, VI - Xiv Sièclevelibor stamenicNo ratings yet

- The Fortunes of Apuleius and the Golden Ass: A Study in Transmission and ReceptionFrom EverandThe Fortunes of Apuleius and the Golden Ass: A Study in Transmission and ReceptionNo ratings yet

- The Atlantic Monthly, Volume 02, No. 09, July, 1858 A Magazine of Literature, Art, and PoliticsFrom EverandThe Atlantic Monthly, Volume 02, No. 09, July, 1858 A Magazine of Literature, Art, and PoliticsNo ratings yet

- Carolingian ArtDocument11 pagesCarolingian ArtJohannes de SilentioNo ratings yet

- Alfred the Great (Barnes & Noble Digital Library): The Truth Teller, Maker of England, 848-899From EverandAlfred the Great (Barnes & Noble Digital Library): The Truth Teller, Maker of England, 848-899No ratings yet

- Poems of Giosuè Carducci, Translated with two introductory essays: I. Giosuè Carducci and the Hellenic reaction in Italy. II. Carducci and the classic realismFrom EverandPoems of Giosuè Carducci, Translated with two introductory essays: I. Giosuè Carducci and the Hellenic reaction in Italy. II. Carducci and the classic realismNo ratings yet

- History of the English People, Volume V Puritan England, 1603-1660From EverandHistory of the English People, Volume V Puritan England, 1603-1660No ratings yet

- Crusade Against the Grail: The Struggle between the Cathars, the Templars, and the Church of RomeFrom EverandCrusade Against the Grail: The Struggle between the Cathars, the Templars, and the Church of RomeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (13)

- Coptic LiturgyDocument5 pagesCoptic LiturgyspamdetectorjclNo ratings yet

- Robins - 2019 - HISTORIA APOLLONII REGIS TYRI A FOURTEENTH-CENTURY VERSION - IntroDocument18 pagesRobins - 2019 - HISTORIA APOLLONII REGIS TYRI A FOURTEENTH-CENTURY VERSION - IntromaletrejoNo ratings yet

- Legge. Philosophumena Formerly Attributed To Origen, But Now To Hippolytus. Translated From The Text of Cruice. 1921. Vol. 1.Document212 pagesLegge. Philosophumena Formerly Attributed To Origen, But Now To Hippolytus. Translated From The Text of Cruice. 1921. Vol. 1.Patrologia Latina, Graeca et OrientalisNo ratings yet

- Instant Download Essentials of Sociology 12th Edition Henslin Solutions Manual PDF Full ChapterDocument33 pagesInstant Download Essentials of Sociology 12th Edition Henslin Solutions Manual PDF Full ChapterJoshuaSnowexds100% (7)

- Instant Download Principles of Chemistry A Molecular Approach 2nd Edition Tro Test Bank PDF Full ChapterDocument32 pagesInstant Download Principles of Chemistry A Molecular Approach 2nd Edition Tro Test Bank PDF Full Chapterdandyizemanuree9nn2y100% (6)

- NewJerusalems 17 Hoffmann Wolf FromPontiusToPilate 2009 EngRusDocument24 pagesNewJerusalems 17 Hoffmann Wolf FromPontiusToPilate 2009 EngRusNorthman57No ratings yet

- The Great Events by Famous Historians, Volume 08 The Later Renaissance: from Gutenberg to the ReformationFrom EverandThe Great Events by Famous Historians, Volume 08 The Later Renaissance: from Gutenberg to the ReformationNo ratings yet

- Notes and Queries, Vol. IV, Number 102, October 11, 1851 A Medium of Inter-communication for Literary Men, Artists, Antiquaries, Genealogists, etc.From EverandNotes and Queries, Vol. IV, Number 102, October 11, 1851 A Medium of Inter-communication for Literary Men, Artists, Antiquaries, Genealogists, etc.No ratings yet

- Hackett. Anne Boleyn - Book.ChapterDocument28 pagesHackett. Anne Boleyn - Book.ChapterAstelle R. LevantNo ratings yet

- John of SalisburyDocument3 pagesJohn of SalisburycalugayNo ratings yet

- The Inquisition - A Political And Military Study Of Its EstablishmentFrom EverandThe Inquisition - A Political And Military Study Of Its EstablishmentNo ratings yet

- Instant Download Psychology 4th Edition Schacter Test Bank PDF Full ChapterDocument32 pagesInstant Download Psychology 4th Edition Schacter Test Bank PDF Full Chapterariadneamelindasx7e100% (6)

- The Wanderings and Homes of Manuscripts (Barnes & Noble Digital Library)From EverandThe Wanderings and Homes of Manuscripts (Barnes & Noble Digital Library)No ratings yet

- 1.) Book of Kells: Recuyell of The Historyes of Troye or Recueil Des Histoires de Troye, Is A French Courtly RomanceDocument5 pages1.) Book of Kells: Recuyell of The Historyes of Troye or Recueil Des Histoires de Troye, Is A French Courtly Romancepakbet69No ratings yet

- Instant Download Test Bank For Life in The Universe 3rd Edition Bennett PDF EbookDocument32 pagesInstant Download Test Bank For Life in The Universe 3rd Edition Bennett PDF Ebookhaydencraigpkrczjbgqe100% (13)

- Jas Elsner, Joan-Pau Rubies Voyages and Visions Towards A Cultural History of Travel Reaktion Books - Critical Views PDFDocument355 pagesJas Elsner, Joan-Pau Rubies Voyages and Visions Towards A Cultural History of Travel Reaktion Books - Critical Views PDFkelly_torres_1650% (2)

- Chadwick RenacimientoDocument16 pagesChadwick RenacimientoLoveless MichaelisNo ratings yet

- Instant Download Essentials of American Government Roots and Reform 2011 10th Edition Oconnor Test Bank PDF Full ChapterDocument32 pagesInstant Download Essentials of American Government Roots and Reform 2011 10th Edition Oconnor Test Bank PDF Full ChapterGinaRobinsoneoib100% (9)

- Before the Gregorian Reform: The Latin Church at the Turn of the First MillenniumFrom EverandBefore the Gregorian Reform: The Latin Church at the Turn of the First MillenniumNo ratings yet

- ItinerariusDocument382 pagesItinerariusMarg NNo ratings yet

- Instant Download Communicate 14th Edition Verderber Test Bank PDF Full ChapterDocument32 pagesInstant Download Communicate 14th Edition Verderber Test Bank PDF Full ChapterCarolineAvilaijke100% (10)

- Reassessing Women's Libraries in Late Medieval France - The Case of Jeanne de LavalDocument29 pagesReassessing Women's Libraries in Late Medieval France - The Case of Jeanne de LavalCarmilla von KarnsteinNo ratings yet

- Solutions Manual To Accompany Mathematics of Interest Rates and Finance 9780130461827Document32 pagesSolutions Manual To Accompany Mathematics of Interest Rates and Finance 9780130461827paulsuarezearojnmgyiNo ratings yet

- Collins. Renaissance EpigraphyDocument20 pagesCollins. Renaissance EpigraphyAlberto CalderiniNo ratings yet

- Historial Mith of Papise JoannaDocument9 pagesHistorial Mith of Papise JoannajavictoriNo ratings yet

- The Age of Reason Begins: The Story of Civilization, Volume VIIFrom EverandThe Age of Reason Begins: The Story of Civilization, Volume VIIRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (8)

- Conquerors, Brides, and Concubines: Interfaith Relations and Social Power in Medieval IberiaFrom EverandConquerors, Brides, and Concubines: Interfaith Relations and Social Power in Medieval IberiaRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Death of SenecaDocument4 pagesDeath of Senecadavidluna19813894No ratings yet

- ORMROD - The Use of English. Language, Law, and Political Culture PDFDocument39 pagesORMROD - The Use of English. Language, Law, and Political Culture PDFdavidluna19813894No ratings yet

- Medieval Academy of AmericaDocument18 pagesMedieval Academy of Americadavidluna19813894No ratings yet

- FDocument80 pagesFdavidluna19813894No ratings yet

- ENENKEL - Zoology in Early Modern Culture PDFDocument547 pagesENENKEL - Zoology in Early Modern Culture PDFdavidluna19813894100% (1)

- POLLARD - The Tyranny of Richard IIIDocument19 pagesPOLLARD - The Tyranny of Richard IIIdavidluna19813894100% (1)

- PUETT - Ritual and Ritual ObligationsDocument8 pagesPUETT - Ritual and Ritual Obligationsdavidluna19813894No ratings yet

- Byzantine Imperial CoronationsDocument33 pagesByzantine Imperial Coronationsdavidluna19813894No ratings yet

- PICK - Genrer in Early Spanish CronicleDocument23 pagesPICK - Genrer in Early Spanish Cronicledavidluna19813894No ratings yet

- MOOJI - Time and Mind PDFDocument301 pagesMOOJI - Time and Mind PDFdavidluna19813894100% (1)

- Stephenson Byz AristocracyDocument13 pagesStephenson Byz Aristocracydavidluna19813894No ratings yet

- BR - Gil Vicente - Auto de La Sibila CasandraDocument2 pagesBR - Gil Vicente - Auto de La Sibila Casandradavidluna19813894No ratings yet

- BR - Clothes Make TheMan Female Cross DressingDocument3 pagesBR - Clothes Make TheMan Female Cross Dressingdavidluna19813894No ratings yet

- PITAWAY - The Political Apropiation of Jhon Lydate's Fall of PrincesDocument288 pagesPITAWAY - The Political Apropiation of Jhon Lydate's Fall of Princesdavidluna19813894No ratings yet

- BOURLAND - Boccaccio and The DecameronDocument291 pagesBOURLAND - Boccaccio and The Decamerondavidluna19813894No ratings yet

- Kings & Queens 4 - Royal Studies Network - Program DraftDocument13 pagesKings & Queens 4 - Royal Studies Network - Program Draftdavidluna19813894No ratings yet

- ROBINSON - The Wheel of FortuneDocument11 pagesROBINSON - The Wheel of Fortunedavidluna19813894No ratings yet

- Call For Contributions History of MonarchyDocument1 pageCall For Contributions History of Monarchydavidluna19813894No ratings yet

- SWARTZ - Aquinas. On Law, TirannyDocument13 pagesSWARTZ - Aquinas. On Law, Tirannydavidluna19813894No ratings yet

- Journeys in Grief. Theorizing Mourning RitualsDocument12 pagesJourneys in Grief. Theorizing Mourning Ritualsdavidluna19813894No ratings yet

- Coronations. Medieval and Early Modern Monarchic RitualDocument180 pagesCoronations. Medieval and Early Modern Monarchic Ritualdavidluna1981389450% (2)

- Reimagining Time in School For All StudentsDocument24 pagesReimagining Time in School For All StudentsRahul ShahNo ratings yet

- 16 - F.Y.B.Com. Geography PDFDocument5 pages16 - F.Y.B.Com. Geography PDFEmtihas ShaikhNo ratings yet

- FV EAPP Gr12 M6 NGDocument9 pagesFV EAPP Gr12 M6 NGCyrylle FuntanaresNo ratings yet

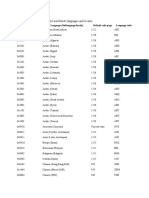

- The Following Table Shows The Worldwide Languages and LocalesDocument12 pagesThe Following Table Shows The Worldwide Languages and LocalesOscar Mauricio Vargas UribeNo ratings yet

- Constructing A Replacement For The Soul - BourbonDocument258 pagesConstructing A Replacement For The Soul - BourbonInteresting ResearchNo ratings yet

- Dixon IlawDocument11 pagesDixon IlawKristy LeungNo ratings yet

- Definition of Liberal by Jan IrvinDocument6 pagesDefinition of Liberal by Jan Irvin8thestate100% (1)

- Scala HarterDocument2 pagesScala HarterelaendilNo ratings yet

- Taking Responsibility: From Pupil To StudentDocument22 pagesTaking Responsibility: From Pupil To StudentJacob AabroeNo ratings yet

- Study-Guide-Css - Work in Team EnvironmentDocument4 pagesStudy-Guide-Css - Work in Team EnvironmentJohn Roy DizonNo ratings yet

- Criteria For The Classification of Legal SystemDocument8 pagesCriteria For The Classification of Legal Systemdiluuu100% (1)

- Earthquake Event Media Release - 2Document2 pagesEarthquake Event Media Release - 2Lovefor ChristchurchNo ratings yet

- Project Organisation (Self Study)Document30 pagesProject Organisation (Self Study)Jatin VanjaniNo ratings yet

- Leach, MalinowskiDocument46 pagesLeach, Malinowskimani VedantNo ratings yet

- Understanding and Writing Pourquoi StoriesDocument5 pagesUnderstanding and Writing Pourquoi StoriesDiannaGregoryNarotskiNo ratings yet

- Stephen Krashen's Theory of Second Language Acquisition (Assimilação Natural - o Construtivismo No Ensino de Línguas)Document5 pagesStephen Krashen's Theory of Second Language Acquisition (Assimilação Natural - o Construtivismo No Ensino de Línguas)Danilo de OliveiraNo ratings yet

- FORM 138 Template (2015-2016)Document3 pagesFORM 138 Template (2015-2016)Ma Cherry Ann Arabis75% (8)

- Bitch Slapping The Unslappable BitchDocument5 pagesBitch Slapping The Unslappable BitchP. H. Madore100% (1)

- Cinematic Belief - Robert Sinnerbrink PDFDocument23 pagesCinematic Belief - Robert Sinnerbrink PDFThysusNo ratings yet

- KRA For Account ManagerDocument3 pagesKRA For Account Managerd_cheryl56733% (3)

- Learning Episode 2Document9 pagesLearning Episode 2Erna Vie ChavezNo ratings yet

- Roman Life and Manners FriedlanderDocument344 pagesRoman Life and Manners FriedlanderGabrielNo ratings yet

- Rhetorical Analysis EssayDocument2 pagesRhetorical Analysis Essayapi-453110548No ratings yet

- Sample Interview Q and ADocument8 pagesSample Interview Q and AChristian Jay AmoraoNo ratings yet

- Music 5 - Unit 1Document4 pagesMusic 5 - Unit 1api-279660056No ratings yet

- Stillitoe PaulDocument20 pagesStillitoe PaulFacundoPMNo ratings yet

- How To Summons The DeadDocument54 pagesHow To Summons The DeadLuz Estella Nuno100% (1)

- The Influence of Culture Subculture On Consumer BehaviorDocument55 pagesThe Influence of Culture Subculture On Consumer Behaviorvijendra chanda100% (12)

- 03-17 The Medium Is The MessageDocument4 pages03-17 The Medium Is The MessageBalooDPNo ratings yet

- Joseph W. Dubin The Green StarDocument296 pagesJoseph W. Dubin The Green StarNancy NickiesNo ratings yet