Professional Documents

Culture Documents

KEITH CAMERON Montaigne and La Liberté de Conscience

Uploaded by

Santiago Francisco PeñaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

KEITH CAMERON Montaigne and La Liberté de Conscience

Uploaded by

Santiago Francisco PeñaCopyright:

Available Formats

Montaigne and `De la Libert de Conscience' Author(s): Keith Cameron Reviewed work(s): Source: Renaissance Quarterly, Vol.

26, No. 3 (Autumn, 1973), pp. 285-294 Published by: The University of Chicago Press on behalf of the Renaissance Society of America Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2859758 . Accessed: 14/02/2013 11:33

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

The University of Chicago Press and Renaissance Society of America are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Renaissance Quarterly.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded on Thu, 14 Feb 2013 11:33:48 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

MONTAIGNE'S

'DE LA LIBERTE

DE CONSCIENCE'

285

andotherswrote the biography, andthat,with or withouthis knowlwrotein the references to Pole as patron.If edge, someonelikeLupset more thanone personhad a handin it, no one personwould affixhis andcertainly not Pole. signature,

QUEENS COLLEGE OF THE OF NEW YORK CITY UNIVERSITY

and'De la Libertede Conscience' Montaigne

by KEITH

CAMERON

THE NINETEENTH CHAPTER of thesecond bookof MonEssais has of attracted the critics interest because of its taigne's favorable treatment The essayis concerned with ofJuliantheApostate. in 1576andit is saidthat the problems raised by the Paix deMonsieur wasinfluenced in his ofJulian Montaigne's by Bodin'sremarks portrait del'Histoire andAmmian Methode Marcellinus' lifeof theEmperor.1 Vilthe essayasan example of theway Montaigne his reveals ley interprets 'IIestcertain etait personality: Montaigne penequ'endefendant Julien trede sonsujetet qu'iltenait'afairepasser en noussaconviction. Donc, il estvraiqueles essais de cettesortecontribuent "a la peinture de MonLouisCons taigne,maisils n'ont pas ete composes pour le peindre.'2 of Montaigne and showshow the essaithrows the originality stresses light on his attitudetowardsreligion:'Toutesces lignes paraissent au-dessus de la meleedescroyances, ecrites dansun pursoucid'accomet des modement desinterets conduites.'3 Stebelton H.Nulle accentuates

the role of 2.19 in giving an impulse to the revolution in Julian'sfor-

andJosephLeclerin his Toleration tunes4 & theReformation singlesthis out as a reflection the climate of 1576: chapter being upon religious

'The contents,'he writes, 'area little disappointingbecause[Montaigne]

p1. Villey, Les Sources et l'Evolution des Essais de Montaigne, 2nd ed., 2 vols. (Paris, 1933), II, 228-229. 2 Villey, p. 279. 3 Louis Cons, 'Montaigne et Julien l'Apostat,' BHR, 4 (1937), 411-420; 420. 4 Stebelton H. Nulle, 'Julian and the men of letters,' Classical Journal (1959), pp. 257266.

This content downloaded on Thu, 14 Feb 2013 11:33:48 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

286

RENAISSANCE

QUARTERLY

to theendandeffects of thepacification edicts.The chaplimitshimself an attackon the biasandfanaticism constitutes of wellter essentially is It on a lecture addressed to moderation, Catholics, people. meaning Catholic byJeanBodinandhisbook Leaguers.... Inspired particularly del'Histoire, he set out to give, not, asis so oftensaid,a on the M&thode of thatprince, buta morecareful of hisactions, assessment rehabilitation in a century andthiswas, afterall, a greatlessonin impartiality which did not know the meaningof the word!'5 thatthe critics andhistorians we havequotedhave We canconclude allunderlined the twofoldvalueof 2.19, firstasa meansof understandand secondas a reflection of the political character ing Montaigne's the not stressed close have climate. They enough,however, relationship betweenthe essaiand the politicalwritingsof the time, or for that cameto takethe example how Montaigne havethey explained matter information It is to tryandsupply thismissing thatthepresent ofJulian. been has undertaken. that Villeyconjectures 2.19 was composed study between1578-8o6which allows us to surmisethat Montaignemost hadthe timeandopportunity to readmanyof thepamphlets probably two yearsaboutthe Paix deMonsieur and writtenduringthe previous

de Bergerac. the Arrangement

of thesecond halfof the1570decTo recreate thepolitical atmosphere to consultthe countless which were adeit is mostprofitable pamphlets of one partyor another the grievances or which expressing published In for the of France. solutions troubles the forward absence solving put a these assumed role in the of newspapers very important pamphlets of newsandpropaganda. a vehiclefor dissemination Theyalsoprovided in theformof political or harangues manifestos to be whether opinions, of the king.7 the attention airedandto attract of pamphlets collections heldat the Whenwe consultthe important andthe Bibliotheque we realize Nationale British Museum how much Histaking,for example, wasinfluenced material. by topical Montaigne was a calculated the title 'De la libertede conscience' attemptto draw of a heated discussion. to 'De la liberte attention contemporary subject wasa key phrase in anydocument with therelide conscience' dealing

5 JosephLecler,S.J., Toleration tr. T. L.Westow, 2 vols. (London, andtheReformation,

1960), II, 175. 6 See Villey, I, 386. 7 See B. L. 0. Richter, 'FrenchRenaissance Pamphlets in the Newberry Library,' Studi Francesi (1960), pp. 220-240.

This content downloaded on Thu, 14 Feb 2013 11:33:48 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

MONTAIGNE'S

'DE LA LIBERTE DE CONSCIENCE'

287

gious problem in the 1570'sand the previous decade.Michel de L'Hoset de la Paix in which he analyzesthe conpital in his Le Butde la Guerre cessionsthat CharlesIX would make were he to sign a peace treatywith the Protestants,remarks:'Or, veoyons ce que le roy leur donne par les traictes.Leur donne il l'estat ou terres?les allege il d'aulcungtribut de leur quitte il aulcung debvoir ou charges?Rien de tout cela. subsides? il Quoy leur donne?IIleur donne une liberte de conscience,ou plus tost il leur laisseleur conscienceen libert6.Appelez-vous cela capituler?'8 Pierre Matthieu, in his history of the period, observes that a similar argument was being used in 1577 by those who criticized the rightwing element which was in favor of war ratherthan Peace. He reprints the 'Antithesespour la paix & contre la guerrede l'an 1577' and it is interestingto note that the reasoningis very reminiscentof Montaigne's:

La paix donnera aux Huguenots ce que la guerreleurpeut oster.Et quoy? la liberte de conscience. Tant de sages Politiques ont confesse que la violence ne violente les ames, que le fer ny le feu n'ont point de pouvoirpouroster lesopinionsunefoisenracineesaux entendemens touchez de religion, que ceste victoire n'appartientqu'a Dieu, Pere de lumiere & de verite, que la force peut bien faire des Hypocrites, des Athees, non des Religieux ny Chrestiens. Si le Roy souffre cesteliberte des Consciences, la ReligionCatholique s'evanouira sousces & toutsonRoyaume desectes, deschismes, & d'erreurs. L'exercice nouveautez, s'empoisonnera libre de ceste religion nouvelle nuyraplus a l'advancementde ses partisans que si on ne l'accorde qu'en secret. ... Quand on leur permet ce qu'ils demandent,qu'on lasche ceste rigueur,la chose devient tant commune & descouverte,que plusieurss'en lassent. r'entrent au grand chemin d'oiuils etoient sortis. C'est pourquoy plusieursont juge n'y avoir moyen plus propre pour esbranler& en fin abbatreune nouvelle religion que d'en permettrel'exercice libre. Ii n'y doitauoirqu'une en unRoyaume. C'est bien dit: mais quandun Roy les y religion trouve il est bien malaise de s'en deffaire.Voulez-vous qu'un ceil poche l'autre ... 9

This method of using antitheticalargumentsis one which appealsto Montaigne throughout the Essaisand the above extractallows us to see how closely the argument follows that development in the last paragraphof 2.19. The similarityof tone between the Essaisand contemporary pamphletsbecomes even clearerwhen we consult the Remonstrance aux Estats pourla Paix.10This work resumesthe main points in the dis8 Michel de CEuvres ed. P. J. S. Dufey, 3 tomes (Paris,1824-26), L'Hospital, completes, Tome 2, p. 199. See also Lecler,II, 78 et seq., who also quotes M. de L'Hospitaland resumes the controversies over edicts from the Edict of Amboise on, and shows the importanceof freedom of consciencein political documents. 9 PierreMatthieu,Histoiredesderniers troubles de France(Lyon, 1597), p. 1l. 10 (Au Souget, Par lean Torque, 1576).

This content downloaded on Thu, 14 Feb 2013 11:33:48 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

288

RENAISSANCE

QUARTERLY

cussionsurrounding the Peacetalksat Blois which arerepeated in so other documents. author would The to many contemporaneous appear of be the Catholic to seeonly one religionin the faith;he wouldprefer statebut,he argues thoseinclined to war,thisis impossible. The against of Montaigne's text is so reminiscent thatit is worthquotingat length:

Maisje desireque ceux qui ont moins approuve (la Paix) entrenten considerationde plusieurschosesque peut estre, ou le zele, ou la passion,ou le peu qu'ilz en ont paty, ou le peu de comparaisonqu'ilz ont de ceux qui en patissoyent,ne leur a peu encor laisser bien considerer.Ilz ne peuvent, (disent-ilz,) endurerny approuver, qu'on laissevivre deux Religions ensemble en France:Je desireroy avec eux qu'il n'y en eust qu'une, selon laquelle Dieu fut servi en tout & par tout comme il appartient.Mais puisque souhaitsn'ont point de lieu, il faut vouloir ce qu'on peut, si on ne peut tout ce qu'on

veut.11

thatMontaigne's attitude to thePaixdeMonsieur It is transparent was We can hardlysay that his echoedby many of his contemporaries. were uniquebut we cansaythatthey views on freedomof conscience to thoseof a moderate But who was thismodwere similar Catholic. is anonymous, Thepamphlet butwe findin 1624thatit erateCatholic? dePhillippes is included in the Memoires deMornay12 with an extended deBloispourla Paix,souslapersonne auxEstats title:Remonstrance d'un Since that date critics have included I'an it Romain, 1576. Catholique the worksof Du Plessis-Mornay.13 We know from the same amongst and thatDu Plessis-Mornayknew wasincorresponMemoires Montaigne in on dencewith him in the 158o's: hisletters he refers several occasions to his friendship with Montaigne.14 The Remonstrance waswritten left the just beforeDu Plessis-Mornay for theKingof Navarre, was Duc d'Anjou whom he to know through Did Montaigne know the true authorship of this docuMontaigne. If he didnot in 1576,he wouldcertainly ment? havedoneso later.And be calleda supporter of the malcontents or the reyet, can Montaigne didnot wishto antagonize formers? It appears to usthatMontaigne the of Navarre and selected usedby one of the carefully King arguments hisown moderate to defend Catholic view. By quotKing'ssupporters

11Remonstrance aux Estats pourla Paix, p. 6.

14 Cf. 'Au restefaitesestat de nostre amitie, comme d'une tres-ancienne, et toutesfois tousjoursrecente;et de mesme foi je le fais de la vostre, que je pense cognoistreen la mienne, mieux qu'en toute autre chose . . . ,' op. cit., I, 274, 'Lettrede M. Du Plessisa M. de Montagne';see also pp. 288, 293, 294.

12 I, 18-19. 13 See R. Patry, Philippe du Plessis-Mornay (Paris, 1933), pp. 40-43.

This content downloaded on Thu, 14 Feb 2013 11:33:48 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

MONTAIGNE'S

'DE LA LIBERTE DE CONSCIENCE'

289

which createdquite a stormMontaigne shows ing from a pamphlet hisreferences hisEssais how topical were.Although aretextually vague, We canevengo further wereclear. theirpolitical repercussions perhaps andlink Montaigne with a political party. Thereis no doubtthatin thosetroubled tornasunyearsof a France der by civil strifegreathopeswere placedon the nobility's settingan and the towards Peace. in example leading people Montaigne, a number of ways, sought to identifyhimselfwith the accepted image of the nobleman15 andhis attitude towards lawsandinnovations16 is reflected in the appeals madeby, or addressed to thatsocialgroupat the timeof the Peacenegotiations. The Duc d'Alen9on was to makea pleafor a

returnto law and order in a Brieveremonstrance a la noblesse de France.17

An accompanying how the conservation of the commentary explains of the the laws: kingdomdepended upon respect

. . . quand l'on abbat les loix fondamentalesd'un royaume, le royaume, le roy & la royaute qui sont bastiesdessus,tombent quand& quand.Bien est vrai qu'il y a bien en un royaume aucunesloix (voire beaucoup) qui se peuvent changer, corriger& abolir, selon la circonstancedu temps & des personnes,& qualite des affaires:mais les loix fondamentalesd'un royaume ne se peuvent jamais abolir, que le royaume ne tombe bien tost apres. Ce sont les loix dont Monseigneur entend ici parler, . . .18

On the question of religious toleration the commentator strikes what is to usa familiar note:

Et combien qu'il sonne mal qu'en une Monarchie y ait deux religions, neantmoins toutes personnesqui ont quelque entendement trouveront plus tolerableensemble les dictesdeux religions (qui recognoissenttoutes deuxJesusChrist& ses commandemens) que la Catholique & l'Atheisme, que les estrangersveulent accouplerensemble.19

As farasthe maintenance of the old lawsandcustoms areconcerned we findthe samesentiments at the beingstated by le Baronde Senesai EtatsGeneraux at Blois (1576-77). He summarizes the strongdesireof the nobility,'c'estque vous [le Roi] nous laissiezvivre & vieillires anciennes & ordonnances de la France.'20 loix, coustumes, Discussing

15Cf.J. P. Boon, 'Montaigne:Du Gentilhommea l'ecrivain,'Modern Philology (1966),

pp. 118-124.

See especiallyEssais, 1.23, et passim. Brieveremonstrance deFrance surlefaictde la Declaration a la noblesse deMonseigneur te Duc d'Alen:on, auRoy TresChrestien faictele 18 de Septembre 1575(1576), in Remonstrance desa Majeste' donnez a Lyon... (Aygenstain,1576). HenryIII... SurlefaictdesdeuxEdicts

17 20 Voir A. D'Aubigne, LesHistoires, 3 tomes (Maille,1618), Tome ii, Livrem, p. 250. Claude de Bauffremont, Baron de Senece,was later to espousethe causeof the League. 18 Ibid., pp. 147-148. 19 Ibid., 149. p.

16

This content downloaded on Thu, 14 Feb 2013 11:33:48 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

290

RENAISSANCE

QUARTERLY

the religious question Senesai seeks the interdiction of the Protestant for the wayward are that there are to be no reprisals churchbut stresses to be taken under the wing of the ruling class: 'qu'il nous soit permis les prendre, eux, leurs familles & biens en nostre protection, sous vostre authorite;cela estantnous nous asseuronsde voir la Justiceen sa premieredignite, & au lustre qu'elle avoit anciennementeste, . . .'21 It is thus with the nobility that Montaigne is siding when he repeats in 2.19 that 'le plus sain party est sans doubte celuy qui maintient et la It is also,aswe have seen,a fairly religionet la police anciennedu pays.'22 orthodox view for a man of his position and social identity to adopt. We are told, however, that this chapter of the Essaisis 'un des plus This can now be applied curieux, le plus singulieret hardipeut-etre.'23 to the political context and also to the use Montaigne has made of the example of Julian the Apostate. This utilization too needs closer examination. is generallyacknowlThe influenceofBodin andAmmianMarcellinus as their importance Montaigne'ssourcesbut edged. Louis Cons stresses says 'par dela Jean Bodin qui avait esquissela rehabilitationde Julien Was it pure l'originalite de Montaigne reste grande et sa hardiesse.'24 coincidencethat Montaigne should decide to develop Bodin's thoughts and make Julian the center of a discussionaround the Peace talks of 1576?We must not overlook, in our haste to provide sources,the intellectualclimate of the age. Bodin and Montaigne were not the only ofJulian.In fact we could ones to have thoughtsabout the rehabilitation a started had been that the movement good decadeearlierby a discisay ple of Pierre de La Ramee, Pierre Martini, a student from Navarre in in 1566and includeda Preface,often Paris.Martinieditedthe Misopogon in which the paved the way towards a new following years, reprinted After of the so-called outlining the life of the EmApostate.25 appraisal peror Martini points out his qualitiesand concludes: 'Magnasomnino laudes eius principis in omni genere virtutis perspeximus:summum sceluse tribuscaussis ortum, naturaelevitate;doctamenillud a4ro-aotas trinae in magicis praecipueartibusperuersitate; denique imperii cupi21 22 23 24 25

Ibid., p. 248.

Essais,ed. Plattard,Societe des Belles Lettres(Paris,1948), p. 99.

Cons, p. 411. Ibid., p. 414.

For more details see J. Bidez, La Vie de l'Empereur Julien, Soc. d'ed. Les Belles

Lettres (Paris, 1965), pp. 34off.

This content downloaded on Thu, 14 Feb 2013 11:33:48 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

MONTAIGNE'S

'DE LA LIBERTE DE CONSCIENCE'

291

ei labem,& miserrimum vitae exitumattulit.'26 ditate;turpissimam Balthazar Grangier, writingaboutthe sametime as the firstEssais of Julian.According the qualities also realized to the were published, of the Abbayede Saint Galliachristiana Grangier enjoyedthe benefice adHelvetios &Rhaetos'27 atNoyon andwas'regius Barthelemy legatus and hencea personof some rankwho, as well as holdingthe above & aumonier duRoy.'He waslaterto translate posts,wasalso'conseiller histranslation LesCeesars.28 It is Danteandin 158oto publish ofJulian's by a shortlife of the emperorin which the authorpraises preceded In the dedicatory to Monsieur, reveals qualities. epistle Grangier Julian's noticedin Martini, an attitude similar to thatalready Bodin,andMonworkhe singles out this'gentil ofJulian's literary taigne.On thesubject espritde celuy qui l'a mis par escrit,lequelle pouvoitfairetenirun honorable rangentreles Empereurs qui ont laisseune bonnememoire la d'estaindre de soy, si se devoyantde la veriteil ne se fut tantefforce de sa de nostresauveur, vouscognoistrez commne memoire parl'abrege deshistoires vie quej'ay recueilly pourla qui ont parlede luy, qu'aussi en peu de place,ce qu'ily a eu de plus gracequ'ila eu a representer en la vie d'unsi bon nombred'Empereurs.'29 loiiableou reprehensible to stress It is apparent wasthusnot alonein hisefforts thatMontaigne the virtuesof the emperor.Where he does differfrom Martiniand andin hisemis in hisdevelopment superstition Grangier aboutJulian's on on his rather than his That atheism phasis apostasy. Montaigne with freedomof conscience is shouldquoteJulianat all in connection moresurprising to the twentieth-century reader thanit would perhaps The reference have been to Montaigne's to Julianin contemporaries. a commonplace when discussing suchcircumstances was virtually the of for their beliefs. Julianprovidedthe religious persecution people of the tyrannical ruler.De Beze in his Du Droit example parexcellence as beingthe epitomyof desMagistrats Julianon threeoccasions quotes

Even his manner of introducingJulian remindsus of Montyranny.30

26

in IulianiImperatoris PierreMartini,Praefatio In IulianiImp.Opera,ed. Misopogonem.

Ezechiel Spanhemius, 2 vols. (Leipzig, 1696), ii, 15. 27 Gallia christiana,Tomus Nonus (1751), Col. 1119.

deDantede l'Enfer(Paris,1596) and the Discours La Come'die de l'Empereur Iuliansur desCaesars(Paris,158o). lesfaictset deportemens

28 29

30

Discours de l'EmpereurIulian ...,

pp. AiiV-Aiii.

II,

Theodore de Beze, Du Droit des Magistrats (1574), ed. R. M. Kingdon (Geneve,

78,

1971), Les Classiques de La Pensee Politique, no. 7, pp. 17, 6o, 67. See also Lecler,

who remarksthatJulianwas being used as an example of the tyrannicalpersecutorof Christians long before the Paix de Monsieur.

This content downloaded on Thu, 14 Feb 2013 11:33:48 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

292

RENAISSANCE

QUARTERLY

'ilfautnoterquele Tyran si execrable ennemi bienestre taigne: pourroit de Dieu, qu'ilfaudroit mesmes contrelui, tesmoin prierexpressement a a contrel'Emtoute l'EgliseChrestienne et est6 exaucee, qui prie, surnomme Julien pereur I'apostat.'31 The usemadeby de BezeofJulianasan example of a tyrannical perraises the question secutor of a comparison betweenthe king of France and a century wasto be usedin England laterasa means of Julian. Julian the danger hencea 'Popish andPagan' of a RomanCatholic, criticizing in 1576between Wasa comparison successor to Charles II.32 established thathe hasbeenthe aimof conHenryIIIandJulian? HenryIIIadmits in France: 'Car stantattacks because of the troubles je n'ignorepasque & adviennent en un estat,le toutesles calamitez privees, publiques qui de clair en la verite des choses tous maux voyant vulguepeu qu'ilsent, il s'enprenda son Prince,1'enaccuse, & le prenda garend, commes'il accidens'33 andwe findin estoiten sapuissance a toussinistres d'obvier laterpamphlets directcomparison betweenHenryandJulian:

.. . il [HenriIII] a ensuivyjulien l'Apostat,lequel s'opposanta l'Eglise, estantblesse en la bataille, confessaqu'on ne pourroit allerallencontrede la puissancedivine... .34 . . nous pouvons veoir estre exprimee en ce mesme Henry de Valois, de poinct en poinct les mceursdeJulien l'Apostat Empereur, qu'a remerquemonsieur sainct Gregoire Nazianzene.... 35

one of the mostpertinent of Henry's is an analysis Probably passages the Peace talks of is behavior where during Henry compared 1576-77, to Julianbecause of his allowingtwo religionsto flourish in one state andbecause of his own alleged'superstition':

Selon ses maximes & preceptes,ce mal adviseHenry a commence en premier lieu a installer en un mesme Royaume deux diverses Religions. C'est ce qui maintient la grandeur d'un Roy, dit son ministre du Belloy, & pour ce des le second an de son regne, faignantavoir perdu tout couragede batailler,encore qu'avecpeu de coups il se fust, s'il eust voulu, rendu victorieux ayant peu d'ennemis en teste: & aymant mieux

31 Ibid.,p. 6o. The use made of historical analogyby the Protestants(althoughCatholics employed a similartechnique)solicitsthis amusingremarkfrom ArnaudSorbinin his Le vraiReveil-matin, de la Maiestede Charles IX (Paris,1574), p. 79v: pour la defense invadentles terres& villes du Prince,ils se disentchastierles 'Quandils [les Protestants] Si le Roy leur fait teste, ou ceux qu'il envoye, Amorrhees,Iebusees,& Chanaaneens. soudainils sont baptisezdes noms de Pharaons, Holofernes,Nabuchodonosors,que ces beaux Apostresleur mettent sur la teste.' 32 See SamuelJohnson, Julian theApostate (London, 1682). 33 duRoy nostre desEstats(Lyon, 1576), p. 4. Sire, faicte en l'assemblee Harengue 34Les Sorceleries de Henryde Valois. . . (Paris,1589), p. 4. 35Les Propheties merveilleuses advenues a l'endroit deHenryde Valois(Paris,1589), p. 21.

This content downloaded on Thu, 14 Feb 2013 11:33:48 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

MONTAIGNE'S

'DE LA LIBERTE DE CONSCIENCE'

293

s'acquerirun renom de Fay-neant ou trop endormy en ses aises, que d'arracherdu champ ou croist la belle fleur de Lis, la plante de l'infecte superstitionqu'il adoroit en son coeur:souz pretexte de Paix & d'Union entre ses subjects,il a fait glisserpar tous les a infectertout le monde, & ne quantonsde son royaume, un Edict plusquetressufisant l'eust peu faireplus apte a ce, s'il n'eust voulu de plain saut se monstrersemblablea un Domitian ou Julian l'Apostat. Car tout ainsi comme s'il eust voulu accorderle Diable avec Dieu, il ordonnapar iceluy que le libre exercicede la religion pretenduereformee, en toute sorte, en toute province & en tout temps seroit de poinct en poinct garde & authorise dans son Royaume, aussibien que la vraye religion.... 36

Is Montaigne thus trying in 2.19 to criticizethe king or, on the contrary, is he making an endeavor to dispel the attack?Montaigne does mention Julian again when he is discussingthe court and royalty as though there were a certainthought associationfor him.37 At the time we are speaking of, Montaigne was greatly in favor at the King of Navarre'scourt and in 1577 he was made a 'gentilhomme ordinairede la chambredu roi de Navarre.'At this period of his life he frequentedthe court at Nerac where he could not have failed to come into contact with the Protestants,amongst whom are to be numbered Du Plessis-Momay, who would certainly have made the comparison between Henry andJulian. Are we thereforeto see in Montaigne'sdefense of the emperor the move to justify the king in the face of his critics?By stressingthe good qualitiesthatJulianpossessedhe may have been making an attempt to stressthe good qualitiesof the king, who like Julianhad a good military record. His remarksthat 'en matierede religion, il estoit vicieux par tout'38could thus be a way of disagreeing with the king's religious policy. These are pure speculationsand it would be foolhardy to support them unreservedly.It can, however, be safely said that to the readerof the Essaisin 158o there would have been a certainintellectuallink between Julian and Henry III in a chapter dealing with religious differand which alludesto a controversialwork by a member of the ences,39 Navarre court.

36Les Meurs,humeurs et comportemens de Henry de Valoisrepresentez au vray depuissa 37 Essais,i, ch. 42, p. 175. And if we are to believe Dr. Armaingaud(Montaigne pam[Paris,191o], pp. 19ff.) that the first paragraphof 2.21.11o refersto Henri III, phlettaire then it is of interestto note that the next sectionin the 1580edition (2.21.112) mentions the EmperorJulian.

38 Op. cit., 2.19.102.

39 As StebeltonH. Nulle, p. 265, concludes:'Eachage has found in him [Julian]what it looked for, what was typical of itself.Just as "all historyis contemporary history,"as the sayinggoes, allJuliansmay be saidto be contemporary. If we knew nothing of a past epoch but its image of the emperor,we would know a good deal of its generaloutlook.'

naissance . . . (Paris, 1589), pp.

11-12.

This content downloaded on Thu, 14 Feb 2013 11:33:48 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

294

RENAISSANCE

QUARTERLY

We can also attribute Montaigne's use of the extended image of We Julianto his love of the paradoxand the employment of antitheses. mentioned earlierhow Montaigne'sessaiseemsto expandthe antitheses to the argumentscirculatingin favor of a single religion and of war. By usingJulianhe was developing a topos in the sameway ashe developed the political ideas, along lines contrary to those of the opposition. His of reason could well be summed up in this matter by an acquaintance his, Florimond de Raemond, who neatly says: 'La foy & les oeuvresne vont pas de mesme pied. Y eut-il jamais homme plus detestableque y eut-iljamais qui eust les moeursplus regleesque luy? l'ApostatJulian? Chacunede ces piecesdeux a sesreiglestoutesdiverses,& toutesdeux ensemble bien unies & joinctes avec la grace de Dieu, font la perfection Chrestienne.'40 Should we not now revise ourjudgment of 2.19? The contentsof the essaiarecertainlyless originalthan may have been thought but it reveals Montaigne's debt to contemporary events and just how topical his chapterwas. It shows how Montaigne in his conservatismis once more to be alliedwith the moderateCatholicnobility,41and how diplomatic in his dealingswith the courts of Franceand Navarrehe could be, thus giving addedsupportto the view that the genius of Montaigne lies not so much in his thought asin the way in which thatthought is presented.42 one of Montaigne'smethods This essaiis importantfor understanding of composition but not for those reasonswhich have been suggested hitherto. No doubt more opinions about Montaigne's techniquesand of his work in procedureswould be revisedaftera carefulreinstatement the political context of his age.

UNIVERSITY OF EXETER

40 Florimond de Raemond: L'Anti-Christ (Lyon, 1597), p. 495. Diderot too in his Pensees philosophiques (Ed. R. Niklaus, Geneva, T.L.F.N0 36, 1957, 30) shares Montaigne's view of Julian. Cf. 'Tels etoient les sentimens de ce Prince, a qui l'on peut reprocher le paganisme, mais non l'apostasie: il passa les premieres annees de sa vie sous diff6rens Maitres & dans diff6rentes ecoles, & fit dans un age plus avance un choix infortune: il decida malheureusement pour le culte de ses ayeux & les Dieux de son pais' (xLm). Although this is an adaptation of Shaftesbury (see note in Verniere edition) we know that Diderot was particularly familiar with 'De la liberte de conscience' because he quotes from it in his Preface to his translation of Shaftesbury's Essay on Merit and Virtue. 41 We disagree with Cons, p. 419, that it was their mutual conservatism which attracted Montaigne to Julian. 42 See my article on 'Montaigne and the Mask,' L'Esprit Createur, 8 (1968), 198-207.

This content downloaded on Thu, 14 Feb 2013 11:33:48 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (120)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- D. Nicol. The Last Centuries of Byzantium, 1261-1453.CUP 1993.Document497 pagesD. Nicol. The Last Centuries of Byzantium, 1261-1453.CUP 1993.Qoruin100% (5)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Luke 16v1-9 Exegetical PaperDocument21 pagesLuke 16v1-9 Exegetical PaperRyan TinettiNo ratings yet

- Tibetan BuddhismDocument115 pagesTibetan Buddhism劉興松No ratings yet

- Wesleyan and Quaker PerfectionismDocument12 pagesWesleyan and Quaker Perfectionismbbishop2059No ratings yet

- Evangelism Sowing and ReapingDocument60 pagesEvangelism Sowing and ReapingJim Poitras100% (2)

- Discernment As Critique in Teresa of Avila and Erasmus of RotterdamDocument20 pagesDiscernment As Critique in Teresa of Avila and Erasmus of RotterdamSantiago Francisco PeñaNo ratings yet

- Luciano Floridi 1995 The Diffusion of Sextus Empiricus S Works in The Renaissance Journal of The History of Ideas LVI 1 PP 63 85 PDFDocument24 pagesLuciano Floridi 1995 The Diffusion of Sextus Empiricus S Works in The Renaissance Journal of The History of Ideas LVI 1 PP 63 85 PDFSantiago Francisco PeñaNo ratings yet

- GREEN Influence of Erasmus Upon Melanchthon, Luther and The ConcordDocument19 pagesGREEN Influence of Erasmus Upon Melanchthon, Luther and The ConcordSantiago Francisco PeñaNo ratings yet

- (Erasmus Studies) Erika Rummel - Erasmus As A Translator of The Classics (1985, University of Toronto Press)Document193 pages(Erasmus Studies) Erika Rummel - Erasmus As A Translator of The Classics (1985, University of Toronto Press)Santiago Francisco PeñaNo ratings yet

- TETEL Rabelais FolengoDocument9 pagesTETEL Rabelais FolengoSantiago Francisco PeñaNo ratings yet

- D P WALKER The Ancient Theology ReseñaDocument4 pagesD P WALKER The Ancient Theology ReseñaSantiago Francisco PeñaNo ratings yet

- DUVAL Ronsard, Aubigné and MisèresDocument18 pagesDUVAL Ronsard, Aubigné and MisèresSantiago Francisco PeñaNo ratings yet

- Reseña de Lazard Por RigolotDocument3 pagesReseña de Lazard Por RigolotSantiago Francisco PeñaNo ratings yet

- KURZ Montaigne and La BoétieDocument49 pagesKURZ Montaigne and La BoétieSantiago Francisco PeñaNo ratings yet

- KURZ Montaigne and La BoétieDocument49 pagesKURZ Montaigne and La BoétieSantiago Francisco PeñaNo ratings yet

- Gregory II of Cypus (Thesis)Document277 pagesGregory II of Cypus (Thesis)goforitandgetit007100% (1)

- Vikings Valkyries Supplement For Mazes Minotaurs RPGDocument51 pagesVikings Valkyries Supplement For Mazes Minotaurs RPGstonegiantNo ratings yet

- Why We Are Shallow - F Sionil JoseDocument3 pagesWhy We Are Shallow - F Sionil JoseBam DisimulacionNo ratings yet

- The Shadow of Lines: Chapter ThreeDocument41 pagesThe Shadow of Lines: Chapter Threeshazad rajNo ratings yet

- RDL 18th Annotation-VeltriDocument37 pagesRDL 18th Annotation-VeltriAnonymous On831wJKlsNo ratings yet

- SamyagdarshanamDocument12 pagesSamyagdarshanamSubi DarbhaNo ratings yet

- Seerah of Prophet Muhammad 92 - Battle of Tabuk 5 Dr. Yasir Qadhi 15th October 2014Document8 pagesSeerah of Prophet Muhammad 92 - Battle of Tabuk 5 Dr. Yasir Qadhi 15th October 2014Yasir Qadhi's Complete Seerah SeriesNo ratings yet

- Bai'At and Its BenefitsDocument5 pagesBai'At and Its Benefitsmohamed abdirahmanNo ratings yet

- D. P.walker Spiritual and Demonic Magic From Ficino To CampanellaDocument258 pagesD. P.walker Spiritual and Demonic Magic From Ficino To Campanellacervanteszetina100% (7)

- KAS 2 NOTES Part 1Document18 pagesKAS 2 NOTES Part 1Sheena Crisostomo Tuazon100% (1)

- Theology of The Church As The Body of Christ Implications For Mission in NigeriaDocument31 pagesTheology of The Church As The Body of Christ Implications For Mission in Nigeriacreyente_madrileñoNo ratings yet

- Absolutism TheoryDocument2 pagesAbsolutism TheoryBenjamin Jr VidalNo ratings yet

- The Human Person and OthersDocument16 pagesThe Human Person and OthersArchie Dei MagaraoNo ratings yet

- Daylight Origins Science Magazine - Number 36 Year 2004Document45 pagesDaylight Origins Science Magazine - Number 36 Year 2004DaylightOriginsNo ratings yet

- Lambeth v. BD of Comm Davidson, 4th Cir. (2005)Document11 pagesLambeth v. BD of Comm Davidson, 4th Cir. (2005)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Malala Youssoufzai SpeechDocument9 pagesMalala Youssoufzai SpeechDaouda ThiamNo ratings yet

- The Reconciliation of Mickey and Her Father To Maintain Their Family's Tie in Robert Lorenz's Film Trouble With The CurveDocument84 pagesThe Reconciliation of Mickey and Her Father To Maintain Their Family's Tie in Robert Lorenz's Film Trouble With The CurveRian AhmadNo ratings yet

- Dissolution Article 1828. Article 1829 Article 1830. Causes of Dissolution Article 1833Document1 pageDissolution Article 1828. Article 1829 Article 1830. Causes of Dissolution Article 1833angelo doceoNo ratings yet

- The Translation Terminology Aid: Dr. Mohammed Attia 2009Document40 pagesThe Translation Terminology Aid: Dr. Mohammed Attia 2009nadheef mubarakNo ratings yet

- Vegetalismo Amazonico, Estudio Sobre Plantas de Poder en Takiwasi, 2016Document127 pagesVegetalismo Amazonico, Estudio Sobre Plantas de Poder en Takiwasi, 2016Nehuen MontenegroNo ratings yet

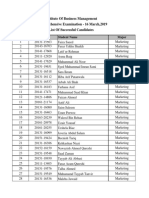

- List of Successful CandidatesDocument13 pagesList of Successful CandidatesAqeel KhanNo ratings yet

- Gec 3 TCW Module FinaleDocument97 pagesGec 3 TCW Module FinaleMa. Josella SalesNo ratings yet

- Exhibitors ListDocument543 pagesExhibitors Listkisnacapri67% (3)

- 21st Century LiteratureDocument9 pages21st Century Literaturelegna.cool999No ratings yet

- 700 Word EssayDocument3 pages700 Word EssayTravis IsgroNo ratings yet

- SNMPTN2020Document2,063 pagesSNMPTN2020AlexanderLinzuNo ratings yet